- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What It Takes to Give a Great Presentation

- Carmine Gallo

Five tips to set yourself apart.

Never underestimate the power of great communication. It can help you land the job of your dreams, attract investors to back your idea, or elevate your stature within your organization. But while there are plenty of good speakers in the world, you can set yourself apart out by being the person who can deliver something great over and over. Here are a few tips for business professionals who want to move from being good speakers to great ones: be concise (the fewer words, the better); never use bullet points (photos and images paired together are more memorable); don’t underestimate the power of your voice (raise and lower it for emphasis); give your audience something extra (unexpected moments will grab their attention); rehearse (the best speakers are the best because they practice — a lot).

I was sitting across the table from a Silicon Valley CEO who had pioneered a technology that touches many of our lives — the flash memory that stores data on smartphones, digital cameras, and computers. He was a frequent guest on CNBC and had been delivering business presentations for at least 20 years before we met. And yet, the CEO wanted to sharpen his public speaking skills.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

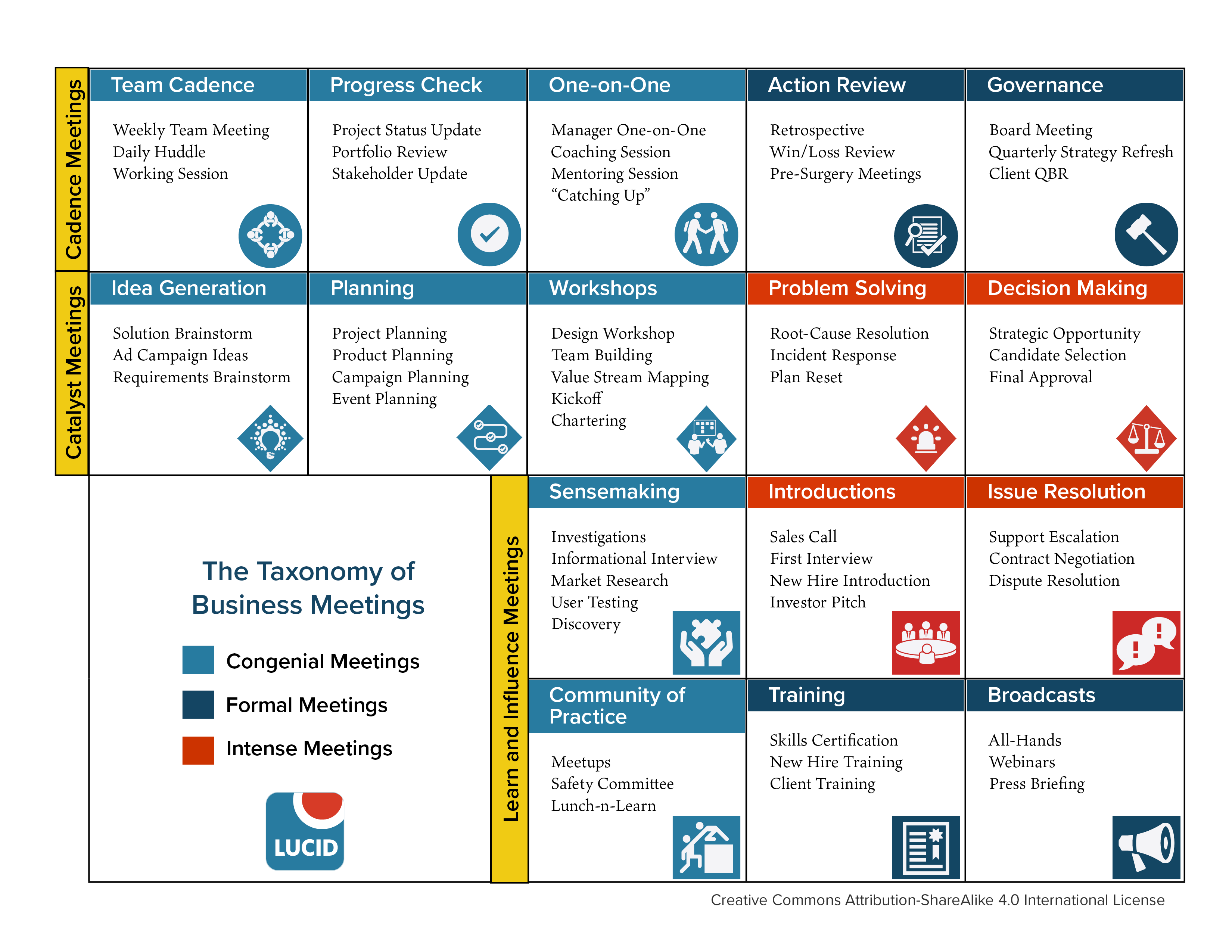

The 16 Types of Business Meetings (and Why They Matter)

It’s not that the advice is wrong, per se. It’s just not specific enough.

- Introduction

- Background: The thinking behind the taxonomy

- Cadence Meetings

- Catalyst Meetings

- Meetings to Evaluate and Influence

- Table: Summary of Types

- Example: How Different Types of Meetings Work Together

For example, it’s not wrong to tell people they need an agenda with clear outcomes listed for every topic. It just doesn’t apply to a lot of situations. An exquisitely detailed agenda for the one-on-one with my boss? For the sales demo? For our morning huddle? Yeah, I don’t think so. For the board meeting or the requirements analysis meeting? Absolutely.

Sometimes an organization has a pervasive problem with meetings. People complain that there are too many meetings, nothing gets done, it’s wasted time, it’s all power and politics instead of productivity—and they start to look for solutions. They find lots of generic advice, and they find lots of this kind of drivel:

Crushing morale, killing productivity – why do offices put up with meetings? There’s no proof that organisations benefit from the endless cycle of these charades, but they can’t stop it. We’re addicted. by Simon Jenkins for the Guardian September 2017

This article is wildly popular. Over 1000 people who hate having their time wasted in meetings paradoxically had extra time they could spend commenting here to express their agreement and outrage.

Mr. Jenkins has clearly struck a nerve. It’s the kind of pandering that drives clicks and sells ads, which makes that a job well done for the Guardian. But it’s also nonsense.

There’s no proof that organizations benefit from meetings? You can only say something like that when you’re speaking too generally for anyone to know what you’re talking about. Because otherwise – did you hear that, sales teams? There’s no proof those client meetings help your company. Go ahead and cancel them! Hospital workers, stop wasting your time in those shift-change meetings! You should know what to do without talking to each other so much – go heal people already! Boards? Board meetings are for losers. Just use chat and email to manage all your governance duties.

When you get specific about the kind of meeting you’re talking about, the generic “meetings waste time” or “you must have 5 people or less” statements become ridiculous, and people who complain about meetings in general sound like childish whingers.

A meeting is not a meeting.

Want to skip the background information? Jump ahead to the taxonomy.

This doesn’t mean that meetings in general work great and that there’s no problem to solve here. It just means that there isn’t a singular meeting problem that has a simple meeting solution .

This is a challenge for us!

At Lucid, we work to help our clients get meaningful business results from their meetings, and to do this, we have to get specific. The coaching we provide for our committee clients is not the same advice we give to leadership teams .

Mr. Jenkins correctly points out that when you invite 20 people to a meeting designed for 5, it doesn’t work anymore. Well, duh. His conclusion is that meetings don’t work. A more useful conclusion is that if you’re going to invite 20 people, you should run a meeting designed to work for 20 people. That’s entirely doable, but it’s also a very different meeting.

In brief: the solution to a meeting problem depends on the kind of meeting.

Which raises the question: what are the different kinds of meetings? If it isn’t useful to provide guidelines for all meetings, is it at least possible to establish useful guidelines for a certain type of meeting? Or do we really need to look at each and every single meeting as if it was totally unique and special?

This question has driven much of our work over the past 10 years.

We found that there is a core structure underlying all successful meetings , acting as a kind of skeleton. Every meeting needs bones, but after that, the kind of animal you get on top of those bones can vary wildly. A fish is not a bird is not a kangaroo, despite the fact that they all have a head and a tail.

We found that meetings work together , and that looking at individual meetings in isolation leads to misunderstandings. It’s like studying a single bee; the drone’s dance doesn’t make a lot of sense unless you know that there are other bees watching. Meetings are designed to beget action that is evaluated and built upon in subsequent meetings, and the sequence and cadence at which these meetings occur drives the momentum of that action. Looking only at a single meeting means you miss the clues that lead to the honey.

We work with facilitators and experts to design agendas and guidebooks for running specific meetings . We’ve seen where the structures look the same, and where they differ. There are lots of specific ways to run a status meeting, but even though there’s a lot of variety between them, every status meeting still looks way more like every other status meeting than it does like any strategic planning session. Mammals are more like other mammals than any of them are like an insect.

And of course we work with clients and hear concerns about all those things that the experts don’t talk about, like how to lead a decent meeting when the group thinks meetings aren’t cool, or how to prepare in advance when your goal is to “wow” everyone during the meeting. We know people worry about how to walk those fine lines between inclusiveness and efficiency, and between appropriate framing and facilitation on the one hand, and manipulation on the other. We hear how they experience specific meetings in the context of getting real work done and can see how priorities shift between getting the content right and getting people connected.

A Taxonomy for Meetings

From all of this, we’ve developed a taxonomy for meetings that we use to help answer these questions:

- Assessing Meeting Performance Maturity : Which kind of meetings does an organization run, and which ones does it need to know how to run well? How well does it run those meetings?

- Meeting Design : If I need to design a new meeting, is there a core pattern I can build on? What factors of the design have the greatest impact on the success of this kind of meeting?

- Meeting Problem Diagnoses: If there is a problem with a meeting, are there common requirements for that kind of meeting that I can check first? Are there things going on in that meeting that might work in other meetings, but are incompatible with success in this one?

- B.S. Filter: Is the advice I’m hearing or reading relevant to the success of this meeting, or is it meant for another sort? Or worse, is it generic B.S.?

Background Work: Forming the Hypothesis

We’re not the first to propose a meeting taxonomy. If you search for “types of meetings” and if you read any books on meetings, you’ll find many ways to break down meetings by type. Most lists include between 4 and 6 different types; things like Issue Resolution meetings and Decision Making meetings.

To build our taxonomy, we started with a set of 6 types and a list of all the different kinds of meetings we could think of, then tried to match them up.

This was frustrating. No matter which list we started with, within a few minutes we always found an example that didn’t fit.

For example, Google used this list of the 6 Types of Meetings from MeetingSift as the definitive list for years. It’s very similar to many other lists out there.

- Status Update Meetings

- Information Sharing Meetings

- Decision Making Meetings

- Problem Solving Meetings

- Innovation Meetings

- Team Building Meetings

So – you tell me. Which one of those does the board meeting fit into? How about the project retrospective? The answer is that meetings like the ones that you might actually find on your calendar can fit into several of these types.

Whenever we found a meeting that didn’t fit, we set it aside and asked “Why?” What is it about that meeting which meant it should be treated differently than these others?

Because we are focused on driving tangible business results, we found we needed to get more specific. In the end, we found that there were three major factors that impact how to approach a meeting.

- The Meeting Intention

- The Meeting Format

The Expected Participation Profile

Our current taxonomy uses these factors to describe 16 distinct meeting types and gives a nod to a significant 17th that falls outside of our scope.

The Differentiators: Intention, Format and Participation Profile

Before we dive into the specific types, let’s take a look at the factors that make them distinct in more detail.

Meeting Intention

The intention behind a meeting is most often expressed as the meeting’s purpose and desired outcomes. In other words, why do people run this kind of meeting? What is it meant to create?

There are two major outcomes for any meeting: a human connection and a work product. We found that many attempts to categorize meetings dealt only with the work product, which often led to bad advice.

For example, the intention of a decision-making meeting is:

- A decision (the work product) and

- Commitment to that decision from the people in the room (a human connection outcome)

It is very easy to run a decision-making meeting that achieves 1 (a decision) but fails to achieve 2 (commitment), and therefore will fail to deliver the expected business result. If you have ever been in a meeting where you’re discussing a decision you thought had already been made, you know this to be true.

Our taxonomy attempts to look at both kinds of outcomes when describing the meeting intention.

When we first started looking at meeting format, we used a standard breakdown of “formal” and “informal” to help distinguish between the board meetings and the team meetings, but we abandoned that pretty quickly because it didn’t hold up in practice.

In practice, we found that while boards have rules that they must follow by law, and they do, this didn’t necessarily mean that the majority of the meeting followed any very strict structure. Many board meetings actually include lots of free-form conversation, which is then briefly formalized to address the legal requirements.

By contrast, we would have considered an Agile team’s daily stand-up meeting to be an informal meeting. Heck, we run those and I don’t always wear shoes. But despite this casual, social informality, the daily stand-up runs according to a very clear set of rules. Every update includes just three things, each one is no longer than 2 minutes, and we never ever ever problem solve during the meeting.

It turns out that formal and informal told us more about a participant’s perception of social anxiety in a meeting than it did about the type or format of a meeting. I experience stand-ups and interviews as informal, largely because I’m in charge and am confident of my role in these meetings. I doubt everyone I interview considers it an informal chat, though, and I imagine our stand-up may feel pretty uptight to someone who wasn’t used to it.

Instead of formal and informal, we found that the strength of the governing rituals and rules had a clearer impact on the meeting’s success. By this measure, the daily stand-up is highly ritualistic, board meetings and brainstorming sessions abide by governing rules but not rigidly so, and initial sales calls and team meetings have very few prescribed boundaries.

This still didn’t quite explain all the variation we saw in meeting formats, however. When we looked at the project status update meeting, we realized it shared some characteristics with the board meeting, but these project meetings aren’t governed by rules and laws in the same way. And while the intention for project updates is always the same—to share information about project work status and manage emerging change—there’s a ton of variation in how people run project status updates. Some teams are very formal and rigid, while others are nearly structure-free. This means our “governing rituals” criteria didn’t work here.

The format characteristic all project status update meetings do share, and that you’ll also see with board meetings, is a dislike of surprises. No project manager wants to show up to the weekly update and get surprised by how far off track the team is, or how they’ve decided to take the project in some new direction. Board members hate this too. For these meetings, surprises are bad bad bad!

Surprises are bad for project updates, but other meetings are held expressly for the purpose of finding something new. The innovation meeting, the get-to-know-you meeting, the problem-solving meeting all hope for serendipity. Going into those meetings, people don’t know what they’ll get, but they try to run the meeting to maximize their chances of something great showing up by the time they’re done.

So, when categorizing meetings based on the meeting format, we looked at both:

- The strength of governing rules or rituals

- The role of serendipity and tolerance for surprise

Last but not least, we felt that who was expected to be at a meeting and how they were meant to interact had a major impact on what needed to happen for the meeting to succeed.

The question behind these criteria is: what kind of reasonable assumptions can we make about how well these people will work together to achieve the desired goal?

Remember: every meeting has both a human connection outcome and a work outcome.

This has many significant design impacts. For example, in meetings with group members that know each other already, you can spend less meeting time on building connections. We don’t do introductions in the daily huddle; we assume the team handled that outside the meeting.

In meetings where the work product is arguably far more important than the human connection, it’s not always necessary for people to like one another or even remember each others’ names as long as the meeting gets them all to the desired goal efficiently. A formal incident investigation meeting does not need the person under investigation to know and like the people on the review board to achieve its goal.

By contrast, some meetings only go well after the team establishes mutual respect and healthy working relationships. The design of these meetings must nurture and enhance those relationships if they are to achieve the desired outcomes. Weekly team meetings often fail because people run them like project status updates instead of team meetings, focusing too heavily on content at the expense of connection, and their teams are weaker for it.

After much slotting and wrangling, we found there were three ways our assumptions about the people in the room influenced the meeting type.

- A known set of people all familiar with one another. Team meetings fit here.

- A group of people brought together to fit a need. Kickoffs, ideation sessions, and workshops all fit here.

- Two distinct groups, with a clear us-them or me-them dynamic, who meet in response to an event. Interviews fit here, as do broadcast meetings and negotiations.

- The expected leadership and participation styles. Every type of meeting has a “default” leader responsible for the meeting design; usually the boss or manager, a facilitator, or the person who requested the meeting. Most also have an expected interaction style for participants that, when encouraged, gets the best results. Some meetings are collaborative, some very conversational, like one-on-ones, and some are very formal – almost hostile. Still others, like the All-Hands broadcast meeting , don’t require any active participation at all.

- The centrality of relationships. Finally, we looked at whether the meeting’s success depended on the group working well together. Nearly every meeting that teams repeat as part of their day-to-day operations works best when team members get along, and becomes torturous when they don’t. Outside of regular team meetings, there are also meetings designed explicitly to establish positive relationships, such as the first introduction, interviews, and team chartering workshops. In all these cases, a successful meeting design must take relationships into account.

Criteria We Considered and Rejected

There are lots of other factors that influence how you plan and run any given meeting, but we felt that they didn’t warrant creating a whole new type. Here are some of the criteria that impact meeting design, but that we didn’t use when defining types.

Location and Resources

Face-to-face or remote, walking or sitting, sticky notes or electronic documents; there’s no question that the meeting logistics have an impact. They don’t, however, change the underlying goals or core structure for a meeting. They simply modify how you execute it.

A design workshop for creating a new logo will deal with different content than one for developing a new country-sponsored health plan or one for creating a nuclear submarine. At the human level, however, each of these design workshops needs to accomplish the same thing by engaging the creative and collaborative genius of the participants in generating innovative solutions. Similarly, project meetings in every field look at time, progress, and budget. The content changes, but the core goals and format do not.

This one is like logistics. You absolutely have to change how you run a meeting with 20 people from how you led the same meeting with 5. But again, the goals, the sequence of steps, the governing rituals – none of that changes. In general, smaller meetings are easier to run and more successful on a day-to-day basis. But if you legitimately need 20 people involved in that decision, and sometimes you do, that is an issue of scale rather than kind.

Operating Context

What comes before the meeting and what’s happening in the larger ecosystem can have a huge impact on how a team approaches a meeting. A decision-making meeting held in times of abundance feels radically different than one you run to try and figure out how to save a sinking ship . Even so, the underlying principles for sound decision-making remain the same. Some situations absolutely make it much harder to succeed, but they don’t, in our opinion, make it a fundamentally different kind of meeting.

Now, given that extended lead-up, what types did we end up with?

The 16 (+1) Types of Meetings

I’ve broken our list into three main groupings below and provided details for each type. Then, at the end, you’ll find a table with all the meeting types listed for easy comparison and a spreadsheet you can download.

Quickly, here’s the list. Details are below.

Team Cadence Meetings

- Progress Updates

One-on-Ones

- Action Review Meetings

Governance Cadence Meetings

- Idea Generation Meetings

Planning Meetings

- Decision Making Meeting

Sensemaking

- Introductions

Issue Resolution Meetings

- Community of Practice Meetings

Training Sessions

Broadcast meetings.

Want to learn more about this chart? See the follow-up post on the Periodic Table of Meetings .

Cadence Meetings We Review, Renew, Refine – Meetings with Known Participants and Predictable Patterns

As we do the work of our organizations, we learn. The plans we made on day one may work out the way we expected, but maybe not. New stuff comes up and before too long it becomes obvious that we need to adjust course.

Organizations use these meetings to review performance, renew team connections, and refine their approach based on what they’ve learned.

All of these meetings involve an established group of people, with perhaps the occasional guest. Most happen at regular and predictable intervals, making up the strategic and operational cadence of the organization.

These meetings all follow a regularized pattern; each meeting works basically like the last one and teams know what to expect. Because the participants and the format are predicatable, these meetings often require less up-front planning and less specialized facilitation expertise to succeed.

The meeting types in this group are:

- Ensure group cohesion

- Drive execution

- the Weekly Team Meeting

- the Daily Huddle

- the Shift-Change Meeting

- a Regular Committee Meeting

- the Sales Team Check-In Meeting

Expected Participation Profile

These meetings are typically led by the “boss” or manager, but they can be effectively led by any team member. The best results happen when everyone invited engages collaboratively. Healthy relationships are important to meeting success.

Meeting Format

Team cadence meetings follow a regular pattern or standard agenda, which can be very ritualistic. Team meetings should surface new information and challenges, but big surprises are not welcome here. (Unless they’re super awesome!) These meetings are about keeping an established team personally connected and moving towards a common goal, and not about inspiring major change.

To learn more, visit our Team Cadence Meetings Resource Center.

Back to the list of types ⇧

Progress Checks

- Maintain project momentum

- Ensure mutual accountability

- the Project Status Meeting

- the Client Check-In

Project managers and account managers lead these meetings, and everyone else participates in a fairly structured way. In many ways, these meetings are designed to inform and reassure people that everyone else on the team is doing what they said they’d do, or if not, to figure out what they all need to do to get back on track. Functional relationships matter, but it’s not as important to the overall result that these people enjoy each other’s company. Because these meetings are mostly designed to “make sure everything is still working”, which matters to project success and the organization’s ability to plan, they can often be very boring for the individual contributors who already know what’s going on with their work.

Project updates follow a regular pattern. Some are very strict, others less so; this varies by the team and the kind of work they do. Surprises are entirely unwelcome. Any major surprise will cause a meeting failure and derail the planned agenda.

To learn more, visit our Progress Check Meetings Resource Center.

- Career and personal development

- Individual accountability

- Relationship maintenance

- the Manager-Employee One-on-One

- a Coaching Session

- a Mentorship Meeting

- the “Check In” with an Important Stakeholder

These meetings involve two people with an established relationship. The quality of that relationship is critical to success in these meetings, and leadership may alternate between the participants based on their individual goals. While these meetings may follow an agenda, the style is entirely conversational. In some instances, the only distinction between a one-on-one and a plain ol’ conversation is the fact that the meeting was scheduled in advance to address a specific topic.

One-on-ones are the loosey goosiest meetings in this set. Experienced and dedicated leaders will develop an approach to one-on-ones that they use often, but the intimate nature of these meetings defies rigid structure. People tend not to enjoy surprises in one-on-ones, but they infinitely prefer to learn surprising news in these meetings rather than in a team or governance cadence meeting. If you’re going to quit or fly to the moon or you’ve just invented the cure to aging, you’re way better off telling your manager privately before you share that with the board.

To learn more, visit our One-on-One Meetings Resource Center.

Action Reviews

- Learning: gain insight

- Develop confidence

- Generate recommendations for change

- Project and Agile Retrospectives

- After Action Reviews and Before Action Reviews (Military)

- Pre-Surgery Meetings (Healthcare)

- Win/Loss Review (Sales)

These meetings are led by a designated person from the team. When run well, action reviews demand highly engaged and structured participation from everyone present. Because action reviews are so structured, they don’t require the individuals involved to be great friends. They do, however, require professionalism, focus, a commitment to building psychological safety, and strong engagement. Action reviews that happen too infrequently or too far away in time from the action tend to become more conversational and less powerful.

Action reviews are highly ritualistic; these are the kind of meetings that inspire the use of the word “ritual”. The action review is a tool for continuous learning; the more frequently these are run and the tighter the team gets, the faster they learn and improve. Teams can and will change how they run these meetings over time based on what they’ve learned, and this avid pursuit of change for the better is itself part of the ritual. Action reviews take surprise in stride. The whole point is to learn and then refine future action, so while huge surprises may cause chagrin, they are embraced as lessons and used accordingly.

Can you tell these are some of my favorite meetings?

To learn more, visit our Action Review Meetings Resource Center.

- Strategic definition and oversight

- Regulatory compliance and monitoring

- Board Meetings

- Quarterly Strategic Reviews

- QBR (a quarterly review between a vendor and client)

The teams involved in governance meetings are known in advance but don’t necessarily work together often. Nor do they need to; these aren’t the kind of meetings where everyone has to be pals to get good results. These meetings are led by a chair or official company representative, and participation is structured. This means that while there are often times for free conversation during a governance meeting, much of the participation falls into prescribed patterns. These are often the kind of meetings that warrant nicer shoes.

Governance cadence meetings are highly structured. When run professionally, there is always an agenda, it is always shared in advance, and minutes get recorded. Governance meetings are NOT the time for surprises. In fact, best practice for important board meetings includes making sure everyone coming to that meeting gets a personal briefing in advance (see Investigative or One-on-Ones) to ensure no one is surprised in the meeting. A surprise in a governance cadence meeting means someone screwed up.

To learn more, visit our Governance Cadence Meetings Resource Center.

Catalyst Meetings The Right Group to Create Change – Meetings with Participants and Patterns Customized to Fit the Need

New ideas, new plans, projects to start, problems to solve, and decisions to make—these meetings change an organization’s work.

These meetings are all scheduled as needed, and include the people the organizers feel to be best suited for achieving the meeting goals. They succeed when following a thoughtful meeting design and regularly fail when people “wing it”.

Because these meetings are scheduled as needed with whomever is needed, there is a lot more variation in format between meetings. This is the realm of participatory engagement, decision and sense-making activities, and when the group gets larger, trained facilitation.

Idea Generation

- Create a whole bunch of ideas

- Ad Campaign Brainstorming Session

- User Story Brainstorming

- Fundraiser Brainstorming

Idea generation meetings often include participants from an established team, but not always. These meetings are led by a facilitator and participants contribute new ideas in a structured way. While it’s always nice to meet with people you know and like, established relationships don’t necessarily improve outcomes for these meetings. Instead, leaders who want to get the widest variety of ideas possible are better off including participants with diverse perspectives and identities. Relationships are not central here; ideas are.

These meetings start with the presentation of a central premise or challenge, then jump into some form of idea generation. There are loads of idea-generation techniques, all of which involve a way for participants to respond to a central challenge with as many individual ideas as possible. Unlike workshops or problem-solving meetings, the group may not attempt to coalesce or refine their ideas in the meeting. Here, idea volume matters more than anything else. Organizations run these meetings when they aren’t sure what to do yet; the whole meeting is an entreaty to serendipity. As such, there are few governing principles beyond the rule to never interfere with anyone else’s enthusiasm.

To learn more, visit our Idea Generation Meetings Resource Center.

- Create plans

- Secure commitment to implementing the plans

- Project Planning

- Campaign Planning (Marketing)

- Product Roadmap Planning

- and so on. Every group that makes things has a planning meeting.

Planning meetings often involve an existing team, but also involve other people as needed. Depending on the size and scope of the plans under development, these meetings are led by the project owner or by an outside facilitator. Participants are expected to actively collaborate on the work product. They may or may not have established relationships; if not, some time needs to be spent helping people get to know each other and understand what each of them can contribute. That said, these meetings are about getting a job done, so relationships don’t get central focus.

Planning meetings vary depending on the kind of plan they’re creating, but generally start with an explanation of the overall goal, an analysis of the current situation, and then work through planning details. Planning meetings end with a review and confirmation of the plan created. Planning meetings are not governed by rules nor do they follow specific rituals; the meeting format is dictated more by the planning format than anything else. Because planning meetings happen very early in an endeavor’s life cycle, successful meetings design for serendipity. Anything you can learn during this meeting that makes the plan better is a good thing!

To learn more, visit our Planning Meetings Resource Center.

- Group formation

- Commitment and clarity on execution

- One or more tangible results; real work product comes out of workshops

- Project, Program and Product Kickoffs

- Team Chartering

- Design Workshops

- Value Stream Mapping

- Strategy Workshops

- Team Building workshops

Groups are assembled specifically for these meetings and guided by a designated facilitator. These meetings put future work into motion, so the focus may be split equally between the creation of a shared work product (such as a value stream map or charter document) and team formation since successful team relationships make all the future work easier. Workshops often incorporate many of the elements you find in other types of meetings. For example, a workshop may include information gathering, idea generation, problem solving, and planning altogether.

Because they attempt to achieve so much more than other meetings, workshops take longer to run and way longer to plan and set up. Most workshops expect participants to actively engage and collaborate in the creation of a tangible shared result, and a lot of effort goes into planning very structured ways to ensure that engagement. When it comes to business meetings, these are also often as close to a working party as it gets.

Smaller kickoffs may follow a simple pattern and be held in the team’s regular meeting space, but many workshops take place in a special location; somewhere off-site, outside, or otherwise distinct from the normal work environment. All these meetings start with introductions and level-setting of some kind: a group exercise, a review of the project goals, and perhaps a motivational speech from the sponsor. Then, the team engages in a series of exercises or activities in pursuit of the work product. Since these meetings are long, coffee and cookies may be expected. Workshops conclude with a review of the work product, and often a reflective exercise. That said, while the basic pattern for a workshop is fairly standard, these are bespoke meetings that do not adhere to any particular rituals. The people who plan and facilitate the meeting work hard to create opportunities for serendipity; they want the team to discover things about each other and the work that inspires and engages them.

To learn more, visit our Workshops Resource Center.

Problem Solving

- Find a solution to a problem

- Secure commitment to enact the solution

- Incident Response

- Strategic Issue Resolution

- Major Project Change Resolution

These meetings involve anyone who may have information that helps the group find a solution and anyone who will need to implement the solution. Depending on the urgency of the situation, the meeting will be led by the person in charge (the responsible leader) or a facilitator. Everyone present is expected to collaborate actively, answering all questions and diligently offering assistance. Tight working relationships can help these meetings go more easily, and participants who establish trust can put more energy into finding solutions since they worry less about blame and personal repercussions. That said, these meetings need the participation of the people with the best expertise, and these people may not know each other well. When this happens, the meeting leader should put extra effort into creating safety in the group if they want everyone’s best effort.

Problem solving meetings begin with a situation analysis (what happened, what resources do we have), then a review of options. After the team discusses and selects an option, they create an action plan. We’ve all seen the shortest version of this meeting in movies when the police gather outside of the building full of hostages and collaborate to create their plan. Problem solving meetings follow this basic structure, which can be heavily ritualized in first responder and other teams devoted to quickly solving problems. These strict governing procedures get looser when problems aren’t so urgent, but the basic pattern remains.

In a problem solving meeting, the ugly surprise already happened. Now the team welcomes serendipity, hoping a brilliant solution will emerge.

To learn more, visit our Problem Solving Meetings Resource Center.

Decision Making

- A documented decision

- Commitment to act on that decision

- New Hire Decision

- Go/No-Go Decision

- Logo Selection

- Final Approval of a Standard

Often a decision-making meeting involves a standing team, but like problem solving meetings, not always. These meetings may also include people who will be impacted by the decision or have expertise to share, even if they aren’t directly responsible for implementing the decision. Decision making meetings may be led by a designated facilitator, but more often the senior leader or chair runs them. People participate in decision making meetings as either advisers or decision makers. If the decision under discussion is largely a formality, this participation will be highly structured. If, on the other hand, the group is truly weighing multiple options, the participation style will be much more collaborative. Established relationships are not central to decision making meetings, but the perceived fairness and equanimity of the discussion is. When the group behaves in a way that makes it unsafe to voice concerns, these concerns go unaddressed which then weakens commitment to the decision.

Decision making meetings involve the consideration of options and the selection of a final option. Unlike problem solving meetings that include a search for good options, all that work to figure out the possible options happens before the decision making meeting. In many cases, these meetings are largely a formality intended to finalize and secure commitment to a decision that’s already been made. Ritual is high, and surprises unwelcome. In other situations, the group is weighing multiple options and seeking to make a selection in the meeting. There still shouldn’t be any big surprises, but there’s a whole lot more flexibility. For example, corporate leadership teams run decision-making meetings when faced with unexpected strategic challenges. Many of these teams revert to a structure-free conversational meeting approach; just “talking it out” until they reach a decision. Unfortunately for them, teams make the best decisions when their meetings follow a formal decision-making methodology .

To learn more, visit our Decision Making Meetings Resource Center.

Context Meetings Efforts to Evaluate and Influence – Meetings Between Us and Them, with Info to Share and Questions to Answer

These meetings are all designed to transfer information and intention from one person or group to another. They are scheduled by the person who wants something with the people they want to influence or get something from.

At the surface, that sounds Machiavellian, but the intention here is rarely nefarious. Instead, these meetings often indicate a genuine interest in learning, sharing, and finding ways to come together for mutual benefit.

Because each of these meetings involves some form of social evaluation, the format and rituals have more to do with etiquette and interpersonal skills than regulations or work product, although this is not always the case.

- To learn things that you can use to inform later action

- To gain an understanding of the current state of a project, organization, or system

- Peer Consults (aka Braintrusts)

- Project Discovery Meetings

- Incident Investigations

- Market Research Panels

Expected Participant Profile

These meetings may be led by an interviewer or facilitator. Participants include the people being interviewed and sometimes a set of observers. Engagement in sensemaking meetings may feel conversational, but it always follows a clear question-response structure. Most interviewers work to develop a rapport with the people they’re interviewing, since people often share more freely with people they perceive as friendly and trustworthy. That said, many sensemaking meetings work fine without rapport, because the person sharing information is expecting to benefit from it in the future. For example, if a doctor asks a patient to describe his symptoms, the patient does so willingly because he expects the doctor will use that information to help him feel better.

Many interviews are governed by rules regarding privacy, non-disclosure, and discretion. These formalities may be addressed at the beginning or end of the session. Otherwise, there are no strong patterns for a sensemaking session. Instead, people regularly working in these meetings focus on asking better questions. Like idea generation meetings, information gathering meetings delight in serendipity. Unlike idea generation meetings, however, the goal is not to invent new solutions but rather to uncover existing facts and perspectives.

To learn more, visit our Sensemaking Meetings Resource Center.

- Learn about each other

- Decide whether to continue the relationship

- a Job Interview

- the First Meeting Between Professionals

- the Sales Pitch

- the First Meeting with a Potential Vendor

- the Investor Pitch

Introduction meetings are led by the person who asked for the meeting. The person or people invited to the meeting may also work to lead the discussion, or they may remain largely passive; they get to engage however they see fit because they’re under no obligation to spend any more time here than they feel necessary. People attempt to engage conversationally in most introductions, but when the social stakes increase or the prospect of mutual benefit is significantly imbalanced, the engagement becomes increasingly one-sided.

There are no strict rules for meetings of this type as a whole, but that doesn’t make them ad-hoc informal events. On the contrary, sales teams, company founders, and young professionals spend many long hours working to “hone their pitch”. They hope this careful preparation will reduce the influence of luck and the chances of an unhappy surprise. The flow of the conversation will vary depending on the situation. These meeting can go long, get cut short, and quickly veer into tangents. It’s up to the person who asked for the meeting to ensure the conversation ends with a clear next step.

To learn more, visit our Introduction Meetings Resource Center.

- A new agreement

- Commitment to further the relationship

- Support Team Escalation

- Contract Negotiations and Renewals

- Neighbor Dispute

These meetings are led by a designated negotiator or moderator or, if a neutral party isn’t available, by whoever cares about winning more. All parties are expected to engage in the discussion, although how they engage will depend entirely on the current state of their relationship. If the negotiation is tense, the engagement will be highly structured to prevent any outright breakdown. If the relationship is sound, the negotiation may be conducted in a very conversational style. Obviously, relationship quality plays a central role in the success of a negotiation or issue resolution meeting.

The format for these meetings is entirely dependent on the situation. Formal treaty negotiations between countries follow a very structured and ritualistic format. Negotiations between individual leaders, however, may be hashed out on the golf course. These meetings are a dance, so while surprises may not be welcome, they are expected.

To learn more, visit our Issue Resolution Meetings Resource Center.

Community of Practice Gatherings

- Topic-focused exchange of ideas

- Relationship development

- The Monthly Safety Committee Meeting

- The Project Manager’s Meetup

- The Lunch-n-Learn

The people at these meetings volunteer to be there because they’re interested in the topic. An organizer or chair opens the meeting and introduces any presenters. Participants are expected to engage convivially, ask questions, engage in exercises when appropriate, and network when there isn’t a presentation going. These meetings are part social, part content, and the style is relaxed.

Most of these meetings begin with mingling and light conversation. Then, the organizers will call for the group’s attention and begin the prepared part of the meeting. This could follow a traditional agenda, as they do in a Toastmaster’s meeting, or it may include a group exercise or a presentation by an invited speaker. There’s time for questions, and then more time at the end to resume the casual conversations begun at the meeting start. People in attendance are there to learn about the topic, but also to make connections with others that create opportunities. Many hope for serendipity.

To learn more, visit our Community of Practice Meetings Resource Center.

- To transfer knowledge and skills

- Client Training on a New Product

- New Employee On-Boarding

- Safety Training

The trainer leads training sessions, and participants follow instructions. Participants may be there by choice, or they may be required to attend training by their employer. There is no expectation of collaboration between the trainer and the participants; these are pure transfers of information from one group to the next.

Training session formats vary widely. In the simplest form, the session involves the trainer telling participants what they believe they need to learn, and then participants ask questions. Instructional designers and training professionals can make training sessions way more engaging than that.

To learn more, visit our Training Meetings Resource Center.

- To share information that inspires (or prevents) action

- the All-Hands Meeting

Broadcast meetings are led by the meeting organizer. This person officially starts the meeting and then either runs the presentation or introduces the presenters. People invited to the meeting may have an opportunity to ask questions, but for the most part, they are expected to listen attentively. While they include presentations in the same way a Community of Practice meeting does, they do not provide an opportunity for participants to engage in casual conversation and networking. These are not collaborative events.

Broadcast meetings start and end on time. They begin with brief introductions which are followed by the presentation. Questions may be answered periodically, or held until the last few minutes. Because these meetings include announcements or information intended to inform later action, participants often receive follow-up communication: a copy of the slides, a special offer or invitation, or in the case of an all-hands meeting, a follow-up meeting with the manager to talk about how the big announcement impacts their team. The people leading a broadcast meeting do not expect and do not welcome surprises. The people participating often don’t know what to expect.

To learn more, visit our Broadcast Meetings Resource Center.

That said, I have heard people call broadcasts and training sessions “meetings” on multiple occasions. The all-staff meeting is often just announcements, but people call it a meeting. Project folks will schedule a “meeting to go over the new system” with a client, and that’s basically a lightweight training session.

And if we look at meetings as a tool we use to move information through our organizations, create connections between the people in our organizations, and drive work momentum, broadcast meetings and training sessions certainly fit that bill (as we’ll see in the story below).

Table: All 16 Meeting Types in the Taxonomy of Business Meetings

Now that you’ve seen the details, download this table as a spreadsheet .

Why a spreadsheet?

I expect people to use the taxonomy in one of these ways.

- Take inventory of your organization’s meetings. Which of these do you run, and which should you run? If you’re running one of these kinds of meetings and it isn’t working, what can you see here that may point to a better way?

- Make the taxonomy better. At the end of the day, our list of 16 types is just as arbitrary as MeetingSift’s list of 6 types. What did we miss? What doesn’t work? Let us know. Comments are welcome.

Since all models are wrong the scientist cannot obtain a “correct” one by excessive elaboration. On the contrary following William of Occam he should seek an economical description of natural phenomena. Just as the ability to devise simple but evocative models is the signature of the great scientist so overelaboration and overparameterization is often the mark of mediocrity. George Box in 1976 Journal of the American Statistical Association

Or, stated more economically, “ All models are wrong, but some are useful. ” We’ve tried to hit a mark that’s useful in a way that simpler lists were not. We invite your feedback to tell us how we did.

The 17th Type: BIG Meetings and Conferences

Just when you think you’ve really broadened your horizons and been very thoroughly inclusive, you meet someone who sets you straight. I recently had the pleasure of meeting Maarten Vanneste , who is also a dedicated advocate for meeting design and the meeting design profession . It turns out that while we are using the same words, Maarten works in a very different world where a “meeting” might be a multi-day conference with dozens of sessions and a highly paid keynote speaker or 10. In that world, meeting planners handle logistics, room reservations, lighting requirements, branding, promotions… a wealth of detail that far exceeds anything we might worry about for even the most involved strategic planning workshop.

This is so different, why even mention it?

Because it’s another example of how using a generic word like “meeting” leads to bad assumptions . In case it isn’t clear, in this article when we talk about meetings and meeting design, we’re talking about the 16 types of day-to-day business meetings listed above. Professional meeting planning is a whole different kettle of fish.

How Different Types of Meetings Work Together: A Tale of 25 Meetings

To illustrate how the different kinds of meetings work together, let’s look at a typical sequence of meetings that you might expect to see in the first year of a company’s relationship with a major new client.

This is the story of two companies: ACME, makers of awesome products, and ABC Corp, a company that needs what ACME makes, and all the people working in these two companies that make their business flow.

Sam likes what he saw in the webinar.

Peter calls Sam and they schedule a demo meeting.

Peter tells Jill and the sales team about the upcoming demo with Sam at ABC.

Peter, Jill and Henri prepare before the demo with Sam at ABC.

Peter and Henri give a demo to Sam and Ellen. Ellen is impressed and asks for a quote.

Jill tells the CEO and the rest of the leadership team about the big ABC deal her sales team is working so everyone can prepare.

Peter goes over all the requests in his meeting with Ellen to make sure he understands them, but he’s in no position to authorize those changes. After the meeting, he takes the requests back to Jill.

Peter discusses the contract with Ellen. Ellen wants a better contract.

The leadership team meets to decide how to respond to Ellen’s contract demands. And they do!

Several more negotiation meetings and a security review later, and the deal is signed! Meeting 9: The Sales Handoff (Type: Introduction ) Now that the contract is signed, it’s time to get the project team involved. Peter arranges a meeting between Ellen and Sam and the customer team from ACME: Gary the project manager, Henri the solutions analyst, and Esme the account manager. Going forward, Gary, Henri and Esme will handle all the communication with Sam from ABC Corp. Before the meeting ends, the ACME team schedules a trip to visit ABC Corp the following week.

Peter introduces Sam and Ellen to the ACME team: Gary, Henri, and Esme.

Jill, Peter and the sales review the lessons they learned closing the ABC deal.

Sam escorts Gary, Henri, and Esme through a day of discovery meetings at ABC Corp.

With the background set, everyone works together to draft the project plan. People from the implementation team suggest ways they can easily handle some requirements, and identify items that will require extra time and creativity. They begin a list of issues to solve and one of risks to manage. Starting from the desired end date and working backwards, they work together to build out a draft timeline that shows the critical path, times when they’ll need committed resources from ABC, and places where they just aren’t sure yet what they’ll find. When they feel they understand how the project will go as best they can, they review their draft plan and assign action items. Gary will work on the project timeline, matching their draft plan with available resources and factoring in holidays. Henri will contact Sam to go over questions from the implementation team, and Esme will schedule the kickoff meeting with the client team.

Gary, Henri, and Esme meet with the implementation team members to draft a project plan.

Next, both teams dig into the details. They go over the project plan ACME created and suggest changes. They establish performance goals for how they expect to use the product, making it clear what a successful implementation will look like. They talk about how they’ll communicate during the project and schedule a series of project update meetings. They take breaks and get to know each other, and share cookies. Then they get serious and talk about what might go wrong, and outline what they can do now to increase their odds of success.

At the end, Ellen rejoins them and the group shares their updated project plan with her. They explain changes they made and concerns they still have, and ask a few questions. Finally, they go over exactly who does what next, and set clear expectations about how and when everyone will see progress. With the kickoff complete, they all adjourn to the local pub to relax and continue getting acquainted.

Esme and Ellen lead team members from both companies through the project kickoff

Happily for Gary, the ABC project is right on schedule. For now.

Gary, the other ACME PMs, and the ACME implementation team discuss project progress every week.

Surprise, Gary! Gary hates surprises.

Sam tells Gary there’s been a major shake-up at ABC, and the project is on hold. Oh no! What will Gary do?

Belinda can’t answer those questions, but she helps Gary relax and promises to get a team together who can give him the guidance he needs.

Gary meets one-on-one with his boss Belinda, and they make a plan.

Belinda, Gary, and the leadership team meet find a solution to the problems with the ABC project.

When Gary, Esme, and Sam meet, they each share their constraints and goals, then focus on those places where they seem to be at an impasse. 90 minutes of back and forth, and they reach a deal. The project deadline will move out 2 weeks because of the delay at ABC, but in recompense for the missed deadline, ACME will provide 4 additional training sessions at no charge for all the people at ABC that were just reassigned and need to be brought up to speed. It’s not perfect, but it works and the project gets back on track.

Esme and Gary meet with Sam to negotiate how they’ll finish the project.

ACME trainers teach the ABC team how to use the product.

Gary, Esme and the ACME team, along with Sam and the ABC team, meet with the ABC leadership group. They present their progress, sharing slides with graphs of tasks complete and milestones met. The leadership team asks questions along the way, making sure they understand the implications of the upcoming product launch. When everyone is satisfied, they turn to the CEO who is the decision maker in this meeting.

The launch is approved, and the new system goes live.

Gary, Esme, Sam and their teams ask the new ABC CEO to approve the project. She does!

Everyone agrees that, for the most part, this was a successful project. The client is happy, the product works well, and they made money. Still, there are lessons to learn. Peter and Henri realize that they saw signs that the situation at ABC wasn’t stable in those first few conversations, but they were so eager to win the client that they dismissed them. In the future, they’ll know to pay attention more closely. Gary and the implementation team discovered ways they could keep the project running even when the client isn’t responding, and they’ll build that into their next project plan. At the end of the meeting, the group walks away with a dozen key lessons and ideas for experiments they can try to make future projects even better.

The ACME team meets to discuss what they learned from the ABC project.

The ACME CEO talks about the ABC project with the ACME Board, and gets approval to pursue a new market.

Esme reviews how the product is working out for the ABC team with Sam in the Quarterly Business Review.

This case study becomes a central piece of content in the new marketing campaign approved earlier by ACME’s board.

The ACME marketing team interviews Sam about his experience with their products for a case study.

Sam tells Esme she’ll need to renew the contract with the new head of procurement. Esme gets ready.

Phew! What a journey.

We’ve talked about why it’s important to get specific about the kind of meeting you’re in, and then we looked at our taxonomy for classifying those meetings. Then, we explored how different types of meetings all work together to keep people connected and move work forward in the story of ACME and ABC.

In many ways, the story of Gary, Sam, Esme and the gang is just a story of people doing their jobs. A lot of people work on projects that run like the one described here. Sometimes everything works fine, other times they freak out; nothing unusual there. What you may not have paid much attention to before, and what the story works to highlight, is how often what happens on that journey is determined by the outcome of a meeting. The other thing we can see is that, while those folks on the implementation team may have thought the few meetings they attended were a waste of time, their contributions during meetings helped make the ABC project a success and had a major impact on the direction of the company. When we show up and participate in meetings, we connect with people who will then go on to different types of meetings with other people, connecting the dots across our organization and beyond.

With that in mind, let’s close by revisiting Simon Jenkins’ gripping headline:

Crushing morale, killing productivity – why do offices put up with meetings? There’s no proof that organisations benefit from the endless cycle of these charades, but they can’t stop it. We’re addicted.

Is it possible to run meetings that crush morale and kill productivity? Yes, of course it is. That doesn’t mean, however, that meetings are simply a useless addiction we can’t kick.

It means that some people are running the wrong kind of meetings, and others are running the right meetings in the wrong way. Not everyone does everything well. Have you ever eaten a sandwich from a vending machine? If so, you know that people are capable of producing all kinds of crap that does not reflect well on them or on the larger body of work their offering represents.

In the working world, meetings are where the action is. Run the right meeting well, and you can engage people in meaningful work and drive productivity.

Seems like a pretty nice benefit to me, and hopefully this taxonomy helps us all get there.

General FAQ

Why do meeting types matter.

In the working world, meetings are where the action is. Run the right meeting well, and you can engage people in meaningful work and drive productivity. But if you’re running the wrong meeting, you’re pushing a heavy rock up a tall mountain.

What are the three main categories of meetings?

- Cadence Meetings – the regularly repeated meetings that make up the vast majority of the meetings held in the modern workplace.

- Catalyst Meetings – scheduled as needed, and include the people the organizers feel to be best suited for achieving the meeting goals.

- Learn and Influence Meetings – designed to transfer information and intention from one person or group to another.

What are examples of Cadence Meetings?

- Team cadence meetings

- Progress check meetings

- One-on-One meetings

- Action review meetings

- Governance cadence meetings

What are examples of Catalyst Meetings?

- Idea generation meetings

- Planning meetings

- Problem solving meetings

- Decision making meetings

What are examples of Learn and Influence Meetings?

- Sensemaking meetings

- Issue resolution meetings

- Community of Practice meetings

- Training meetings

- Broadcast meetings

To explore each of the 16 Meeting Types in more detail, visit our Interactive Chart of Meeting Types

Want More? Check out our Online Meeting School!

Categories: meeting design

Elise Keith

- Contact Form

Related Posts

How To Refresh Your Strategic Plan (in 4 Hours or Less)

The Surprising Link Between Climate Change and Virtual Meetings

5 Easy Tips to Make Your Online Sales Meetings Stand Out

IMAGES

VIDEO