Rising Import Tariffs, Falling Export Growth: When Modern Supply Chains Meet Old-Style Protectionism

We examine the impacts of the 2018-2019 U.S. import tariff increases on U.S. export growth through the lens of supply chain linkages. Using 2016 confidential firm-trade linked data, we identify firms that eventually faced tariff increases. They accounted for 84% of all exports and represented 65% of manufacturing employment. For the average affected firm, the implied cost is $900 per worker in new duties. We construct product-level measures of exporters' exposure to import tariff increases and estimate the impact on U.S. export growth. The most exposed products had relatively lower export growth in 2018-2019, with larger effects in 2019. The decline in export growth in 2019Q3, for example, is equivalent to an ad valorem tariff on U.S. exports of 2% for the typical product and up to 4% for products with higher than average exposure.

The Census Bureau's Disclosure Review Board and Disclosure Avoidance Officers have reviewed this data product for unauthorized disclosure of confidential information and have approved the disclosure avoidance practices applied to this release (DRB Approval Numbers: CBDRB- FY19-519, CBDRB-FY20-104, CBDRB-FY20-CES006-004, CBDRB-FY20-CES006-005). We thank Chad Bown, Teresa Fort, Colin Hottman, Soumaya Keynes, CJ Krizan, Frank Li, and seminar and conference participants at the Federal Reserve Board, University of Michigan, Mid-Atlantic International Trade Workshop, U.S. Census Bureau, Stanford University, University of Virginia, Georgetown University, George Washington University, IDB, Rowan University, and FREIT ETOS for helpful comments and discussions. Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Census Bureau, other members of the research staff at the Board of Governors, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, or the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

- January 2, 2020

Mentioned in the News

More from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

- Feldstein Lecture

- Presenter: Cecilia E. Rouse

- Methods Lectures

- Presenter: Susan Athey

- Panel Discussion

- Presenters: Karen Dynan , Karen Glenn, Stephen Goss, Fatih Guvenen & James Pearce

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Research on the impact of covid-19 on import and export strategies.

- 1 College of Science, Tianjin University of Commerce, Tianjin, China

- 2 Laboratory of Basic Psychology, Behavioral Analysis and Programmatic Development PAD-LAB, Catholic University of Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador

- 3 Department of Economics, College of Business Administration, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Due to the spread of COVID-19, the public health crisis is bound to have a huge impact on the world economy and international trade. How to study the import and export strategies under the coronavirus pandemic has become a major issue that many scholars need to solve urgently. Therefore, a two-stage game model is constructed, and the reverse solution method is used to obtain the optimal output of enterprises in importing countries and exporting countries before and after the outbreak of pandemic, as well as the optimal subsidies for enterprises from exporting countries and the optimal import quarantine rate for importing countries. Based on the game between the two countries without the pandemic outbreak, the impact of the pandemic on the output, profits, and social welfare of enterprises in the two countries was compared. Enterprises in exporting countries face double threats from the pandemic and import quarantine fees. The increase in import quarantine fees reduces the social welfare of exporting countries. In order to effectively control the spread of the pandemic, subsidies are an effective means to restore exports to normal. Reasonable collection of import quarantine fees by importing countries can promote bilateral trade, but an excessive collection will be counterproductive. The governments of exporting countries should establish emergency mechanisms and relevant subsidy policies, and enterprises should continuously improve their competitiveness. At the same time, countries should abandon the concept of trade protection and negotiate and cooperate to jointly deal with the pandemic.

Introduction

With the ongoing global pandemic of COVID-19, the unprecedented public health crisis is bound to have a huge negative impact on the world economy, environment and international economic and trade cooperation ( Razzaq et al., 2020 ; Khan et al., 2021 ; Yu et al., 2021 ; Irfan et al., 2022 ). The forecast report released by the World Trade Organization in 2020 pointed out that the pandemic will significantly shrink global trade. After the pandemic outbreak, the scale of global import and export trade showed a sharp decline amid fluctuations. In the first half of 2020, the year-on-year decline in global import and export trade scale reached 11.98% and 13.48%, respectively. The above-mentioned restrictive measures will lead to an obvious trade-inhibitory effect, the direct consequence of which is to weaken the degree of trade liberalization between countries, leading to high market access barriers, sharp rise in trade costs, and may even induce trade protectionism ( Shahzad et al., 2021 ). Therefore, under the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic, how to alleviate the adverse impact of the pandemic to promote international trade to enter the fast lane of recovery has become a major issue that the international community urgently needs to deal with.

Due to the rapid spread of COVID-19 worldwide, countries worldwide have to take trade protection measures ( Xuefeng et al., 2021 ), the international free trade system is increasingly fragile, and new trade barriers are gradually formed. Taking China as an example, in foreign trade, statistics from the General Administration of Customs show that most enterprises with actual import and export results in 2019 are private enterprises, with the number reaching 406,000. In addition, among the export-oriented enterprises in China, small, medium and micro enterprises contribute about 60% of the total national import and export ( Zhang, 2020 ). The addition of such an entry quarantine fee by foreign governments is a severe blow to many export-oriented enterprises facing difficulties in China at the moment. Therefore, export-oriented enterprises must not expand their production blindly because of a series of favorable policies introduced by the state. Each enterprise should reasonably adjust its output and set the optimal production decision according to the international market situation.

The COVID-19 is characterized by high risk, suddenness, and rapid spread and is a typical global public health emergency. It is well known that sudden major public health events usually affect the normal operation of political, economic, and social activities, some scholars conduct research on sudden public health events in the context of social emergency management ( Sun et al., 2014 ; Liang et al., 2019 ; Xi and Zang, 2020 ). Numerous scholars have argued that this COVID-19 has created potential trade barriers and negatively impacted exports. ( Duan et al., 2020 ). noted that more than 18 million SMEs in China were severely affected by the pandemic, most of which have export-led businesses. ( Baldwin and Di Mauro, 2020 ). argued that this COVID-19 pandemic will have a more severe impact on the economy and environment than any other pandemic since World War II, with border closures and factory shutdowns, which will cause a significant drop in exports of the corresponding industries in the countries where the pandemic occurred. Meanwhile, some scholars have proposed policy recommendations for the government to respond to major public health events such as the pandemic from the perspective of maintaining foreign trade. For example Wang and Zhang (2020) , point out that the pandemic may cause significant losses to export country’s economies and trade, and is a major test of national governance system and governance capacity. According to ( Shen, 2020 ), countries need to “stabilize foreign trade” and support import and employment growth by stabilizing the export market, and the government should help enterprises to resume work and production in an orderly manner and introduce policies such as tax reduction and fee reduction. However, these studies usually focus on studying the situation in a single country and fail to consider the interactions between the two countries in terms of import and export.

The related research on the analysis of oligopoly competition strategy is one of the commonly used methods to construct an application scenario model based on game theory, analyze the influence of different strategic behaviors and the changing trend of important variables by means of numerical simulation. Based on the US Rice Export Program to Japan and South Korea ( Lee and Kennedy, 2006 ), attempted to analyze both import markets incorporating econometric estimates and public choice theory in a game-theoretic framework. Du and Wang (2018) proposed a multi-level threshold public goods game model to research how income redistribution affects the evolution of global cooperation. The effect of different thresholds on the strategy was investigated by numerical simulation. Andoni et al. (2021) modeled the problem of deducing how much capacity each player should build as a non-cooperative Stackelberg-Cournot game. Using data-driven analysis to analyze investor decision-making. Based on the game theory ( Yang et al., 2021 ), analyzed the behavior of countries when carrying out regional cooperation to govern the epidemic and put forward specific cooperative income distribution schemes according to the different attributes of the countries. Using numerical simulations, they analyze the effect of the variation of different parameters on the utility of the two countries in different cooperation situations.

Scholars have also conducted many studies on the use of game theory to study bilateral trade. Ferreira and Ferreira (2009) considered an international trade under the Bertrand model with differentiated products and unknown production costs. The impact of tariff changes on corporate profits is analyzed. Yang and Wei (2013) constructed a three-stage game model for the continuation of the United States carbon tariff policy based on a two-stage game model in which the United States implemented a carbon tax policy only on its domestic enterprises and introduced a carbon tariff on imports from China. The impact of carbon tariffs on trade between China and the United States is analyzed. Xie et al. (2016) construct a theoretical game model in which a domestic firm exports to a third country through an intermediary in the third country and competes with a firm located in another country that exports directly to the third country. It is analyzed whether the bargaining power affects the choice of a country’s strategic trade policy when a country firm chooses a third-country intermediary to export its products. Xie et al. (2018) constructed a model of duopoly international market competition in which producers compete on price against the background of product quality differences and with the actual situation of Chinese exporters. And on this basis, using game theory, a country’s optimal strategic trade policy is explored in terms of trade benefits and social welfare. Mizuno and Takauchi (2020) considered a third-market model with a vertical trading structure. The change in optimal export policy as product-substitutability increases is examined, along with a discussion of welfare comparisons between the downstream Gounod and Bertrand cases.

In order to study the impact of the pandemic on import and export strategies and the changes in the profits and social welfare of companies in various countries under the pandemic, we used game theory to model the import and export strategies under the impact of the pandemic. Compared with the existing literature, the contributions of this paper are mainly reflected in the following aspects: under the pandemic, we examined the impact of the collection of import quarantine fees on the production strategies of importing and exporting countries; under the pandemic, we have given the optimal subsidy strategy of exporting countries based on their own social welfare; under the pandemic, we compared the changes in the enterprises’ profits and social welfare of the respective governments after the game between importing and exporting countries, and analyzed the measures that importers and exporters should take to deal with the impact of the pandemic jointly.

Theoretical Model

Problem description and assumptions.

Consider two countries: an exporter ( E country) and an importer ( I country). Similar to the setting in Xie et al. (2018) , Tang et al. (2020) , Mizuno and Takauchi (2020) , Tang et al. (2020) , we assume that each of them has only one enterprise (enterprise E and enterprise I , respectively) that produces a homogeneous product. The products produced by the exporting enterprise E are all exported to the importing I country, and the products of the importing enterprise I can only be sold in its own market, i.e., the importing country is the only consumer of the product. There are two sources of supply in the production market: in addition to the domestic enterprises, they can also import from the exporting E country. We further make the following assumptions. The marginal cost of production, transportation, and tariffs for the exporting country is c E , and the marginal cost of production for the importing country is c I . Since enterprises in the exporting country have relatively low costs, this paper assumes that 0 < c E < c I . Since consumers in the importing I country consume only one homogeneous product, the demand function for the product is:

where a > 0 is the potential price of the product, b > 0 is the sensitivity of price to output, Q E and Q I represent the output of enterprises in the exporting E country and importing I country, respectively.

When a pandemic occurs in the exporting country, the government of the importing country, to protect its national health and the share of its own enterprises in the market, will enhance the exporting country enterprises to impose a unit of production import quarantine fee τ > 0 . At this point, the government of the exporting country, in order to maintain the normal operation of export enterprises, will choose to encourage exports in the short term by giving export enterprises relevant subsidy s > 0 . These assumptions are mostly common practices, thus can be made without the loss of generality of this study. The notations and variables used in our analysis are shown in Table 1 .

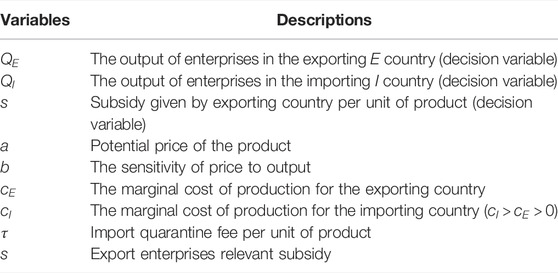

TABLE 1 . Model notations and variables.

Game Model of Two Enterprises in the Absence of a Pandemic

When there is no pandemic, the enterprises of the two countries compete in Cournot game in the consuming country I (importing country). Enterprises’ profits π E ( Q E , Q I ) and π I ( Q E , Q I ) are given by (see Fernanda A.)

The enterprises of each country determine the optimal output by maximizing their profits, and the maximization problem can be expressed as:

From the first-order condition of the optimization problem ( Eq. 1 ) equation, we know that when a > 2 c I − c E , the optimal output of the enterprises in the two countries are:

This leads to the optimal price of the product and the optimal profit of the two enterprises, respectively:

Property 1. In the absence of a pandemic, the enterprise’s optimal output is a decreasing function of the marginal cost of products from domestic enterprise, is an increasing function of the marginal cost of products of the enterprise from other country; the product price is an increasing function of the marginal cost of the product of the enterprise from both countries.Since Q E ∗ − Q I ∗ = c I − c E b and π E ∗ − π I ∗ = ( 2 a − c E − c I ) ( c I − c E ) 9 b , and since c I > c E and a > 2 c I − c E , we obtain the following property.

Property 2. Enterprises in exporting country have higher output and profit than enterprises in importing countries due to their lower marginal costs, i.e.,

Game Model of Two Countries When a Pandemic Occurs in the Exporting Country

When a pandemic occurs in the exporting country, on the one hand, the importing country will impose an additional import quarantine fee τ , and the exporting country will give enterprises subsidy s , the profit structure of exporting enterprises changes. On the other hand, the price of raw materials rises and additional protective equipment lead to an increase in the marginal cost of exporting enterprises, which is recorded as c E m , and c E m > c E . At this point, the game process between the two governments and enterprises is divided into two stages: in the first stage, due to the pandemic in the exporting country, the exporting government determines the optimal subsidy s ∗ to the exporting enterprise based on maximizing its social welfare after learning that the importing country imposes import quarantine fees τ on the exporting enterprise; in the second stage, after the enterprises observe the optimal subsidies given to the enterprises of the exporting country, the enterprises of the two countries conduct the Cournot game to determine their respective optimal output. For this two-stage Stackelberg game, we use the inverse solution method to find the optimal solutions of each stage with reference to Tang et al. (2020) , Tang et al. (2021) , and the superscript denotes the game with pandemic.

Consider the game process of the second stage. The enterprise’s profit is given by

at this time, the profit per unit product of the exporting country’s enterprise has changed. The enterprises in both countries maximize the profits to determine their optimal output Q E m ∗ , Q I m ∗ , the game model is:

where the demand function for the product is P m = a − b ( Q E m + Q I m ) ; τ is a constant, which indicates the import quarantine fees levied by the government of the importing country for enterprises in the exporting country.

From the first-order conditions of the optimization problem (2), the optimal price of the product and the optimal output of the two enterprises are obtained as:

Property 3. When a pandemic occurs in the exporting country, the exporting country’s subsidies for its own enterprises will increase the export volume of its own enterprises, reduce the output of the importing enterprises, and lower the price of the product; the import quarantine fees imposed by the importing country on the exporting country will reduce the export of the exporting country, increase the output of its own enterprises, and increase the price of the product.Since Q E m ∗ ( s ) − Q E m ∗ ( s ) = − c E m + c I + s − τ b , the following property can be obtained.

Property 4. When a pandemic occurs in the exporting country

(1) If s < c E m − c I + τ , the output of enterprises in the exporting country is less than the output of enterprises in the importing country.

(2) If s > c E m − c I + τ , the output of the enterprises in the exporting country is greater than the output of the enterprises in the importing country.

It consists of the profits of enterprises minus subsidy expenses.Substituting the conclusion from Eq. 3 into Eq. 4 yields:

the optimal subsidy from the government of the exporting country to the enterprises should satisfy

From the fact that the second order derivative is less than 0 , there exists an unique optimal solution when a > 2 c E m − c I + 2 τ :

Due to the uncertainty of the pandemic, subsidy policy should be adjusted depending on the situation of the pandemic. Reasonable subsidies will also avoid trade protection by importing countries and promote healthy trade relations between the two countries. However, suppose high export subsidies are given to enterprises across the board for a long period of time. In that case, it will not only harm the interests of enterprises in the importing countries and cause unfair trade competition, but also inhibit technological innovation and weaken the intrinsic motivation of enterprises.

Property 5. When a pandemic occurs in the exporting country, the optimal subsidy from the government of the exporting country to the enterprises is a decreasing function of the import quarantine fees in the importing country, a decreasing function of the marginal cost of the product of the enterprises in the exporting country, and an increasing function of the marginal production cost of the enterprises in the importing country.Substituting s ∗ into Eq. 3 yields the optimal output of the two enterprises in the case of a pandemic in the exporting country when − a + 3 c I 2 − c E m < τ < a + c I 2 − c E m , respectively:

Since the social welfare function of the importing country is:

it consists of the profit of domestic enterprises, consumer surplus and import inspection and quarantine fee income, where C S ( Q m ∗ ) indicates consumer surplus

The optimal price of the product, the profit of the two firms and the social welfare of the two countries can be obtained as:

Property 6. When a pandemic occurs in the exporting country, the optimal output of enterprises in the exporting country, the profits of enterprises and the social welfare of the exporting country are all decreasing functions of import quarantine fees; the optimal output of enterprises in the importing country, the profits of enterprises and the prices of products are all increasing functions of import quarantine fees; when τ < 3 a − 2 c E m − c I 10 , the social welfare of the importing country is an increasing function of import quarantine fees, and when τ > 3 a − 2 c E m − c I 10 , the social welfare of the importing country is a decreasing function of import quarantine fees.

Comparison of Effects in Exporting Countries Without and With Pandemic

Using the absence of a pandemic as a benchmark, we compare the impact on product prices, production and profits of enterprises in both countries, and social welfare in both countries under the scenario of a pandemic in the exporting country.

Impact on Production, Product Prices and Corporate Profits of Enterprises in Both Countries

The optimal output of enterprises in both countries, the optimal price of the product and the social welfare of the governments in both countries are compared for the two scenarios, and the results are as follows:

Property 7.

(1) If c E m + τ < a + 4 c E m + c I 6 , the impact of the pandemic on exporters is small, and timely and effective subsidies from the exporting country’s government lead to an increase in production and profits for the exporting country’s enterprises, a decrease in optimal production and profits for the importing country’s enterprises, and a decrease in product prices.

(2) If a + c I 2 > c E m + τ > a + 4 c E m + c I 6 , the impact of the pandemic on exporters is greater at this time. The occurrence of the pandemic in the exporting country will lead to a reduction in production and profits of enterprises in the exporting country, an increase in production and profits of enterprises in the importing country, and a rise in product prices.

Impact on Social Welfare

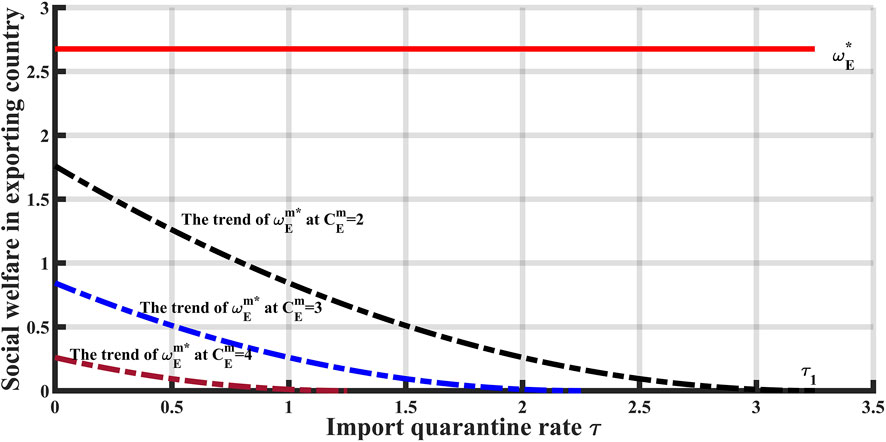

To further analyze the impact of the COVID-19 on social welfare in both countries, numerical simulation is presented. Simulation explored the effect of import quarantine rates and the marginal cost of exporting enterprises on social welfare. For this quantitative demonstration, we assigned values to each parameter based on the assumptions described in the previous sections and the practical implications. The parameters a = 10 , b = 3 , c E = 1 , c I = 3.5 were used as the benchmark case when there is no pandemic. By calculating the optimal social welfare ( ω E m ∗ ) of exporting countries with different c E m and τ , we draw Figure 1 as follows, which describes the trend of social welfare of exporting countries with the import quarantine fee and different production cost.

FIGURE 1 . Trend of social welfare changes in exporting country. (Source: Simulation data for numerical calculations).

The upper horizontal line in Figure 1 is the social welfare of the exporting country in the absence of the pandemic, which is independent of τ and c E m . The lower three curves show the decreasing trend of social welfare in the exporting country for c E m = 2,3,4 , respectively. In addition, the increase of import quarantine fees brings a double blow to exporters; social welfare will be further reduced and decreases as τ increases. With c E m = 2 , for example, the social welfare of exporting countries decreases with the increase of import quarantine rate, and the levy of quarantine fees has a great impact on exporting countries. It is clear from the figure that when the quarantine rate is low, i.e., τ < τ 1 , exporters will still export, but when the quarantine rate exceeds τ 1 , exporters will not be able to afford the excessive tax and stop exporting, and trade is terminated.

In the face of the impact of the pandemic and the import quarantine fees imposed by importing countries, the government should strive to improve the competitiveness of its enterprises. Exporters should accelerate the pace of transformation and upgrading, reduce the marginal cost of production, continuously improve logistics efficiency, review the situation to improve their own management capacity and risk resistance and enhance the position of their products in the industrial chain and the competitiveness of the international market.

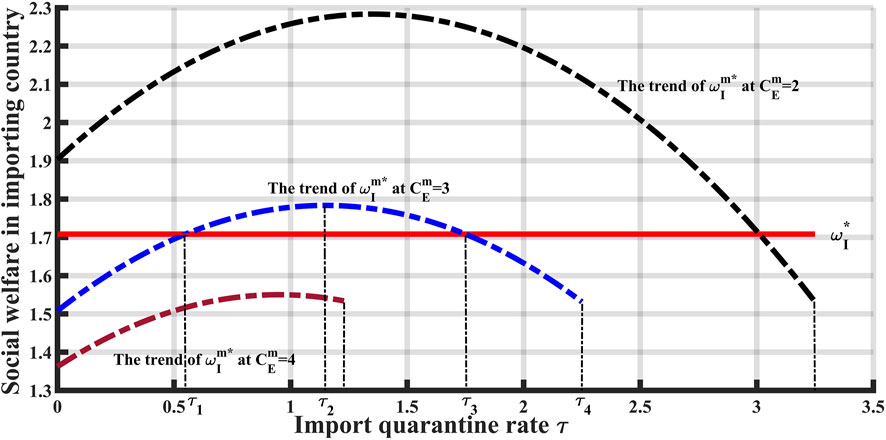

The trends of social welfare ( ω E m ∗ ) in importing countries with τ and c E m are shown in Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2 . Trends of social welfare changes in importing countries. (Source: Simulation data for numerical calculations).

The horizontal line in Figure 2 is the social welfare of the importing country in the absence of the pandemic, which is independent of τ and c E m . The three curves show the change of social welfare of importing countries with τ when c E m = 2,3,4 , respectively, and the curves show an increasing and then decreasing trend. Taking c E m = 3 as an example, it can be clearly seen that: 1) When τ < τ 2 The social welfare of the importing country is an increasing function of the import quarantine fee, and increasing the import quarantine fee will increase the social welfare. When τ 2 < τ < τ 4 , the social welfare of the importing country is a decreasing function of the import quarantine fee, and increasing the import quarantine fee at this time will make the social welfare decrease, indicating that the high quarantine fee does not improve the social welfare of the importing country; 2) And when τ < τ 1 or τ 3 < τ < τ 4 , the social welfare is lower than that of in the absence of pandemic, indicating that when the quarantine fee is too low or too high, the social welfare of the importing country due to the pandemic will lower; and when τ 1 < τ < τ 3 , the social welfare of the importing country is higher than before the pandemic, indicating that an appropriate import quarantine fee will increase the social welfare of the importing country; 3) When τ > τ 4 , the exporting country will not export the product due to the high import quarantine fee and the trade between the importing and exporting countries will stop.

To avoid trade frictions between bilateral countries and to avoid the increase of product prices in the domestic market and the reduction of consumer surplus, the importing country should only reasonably levy import quarantine fees to improve the market competitiveness of domestic enterprises, thereby increasing corporate profits and social welfare. However, the import quarantine fee levied by the importing country cannot be too high, otherwise, it will not only seriously damage the social welfare of the exporting country but also reduce the social welfare of the importing country itself, which is not conducive to the upgrading and transformation of domestic enterprises and the adjustment of industrial structure.

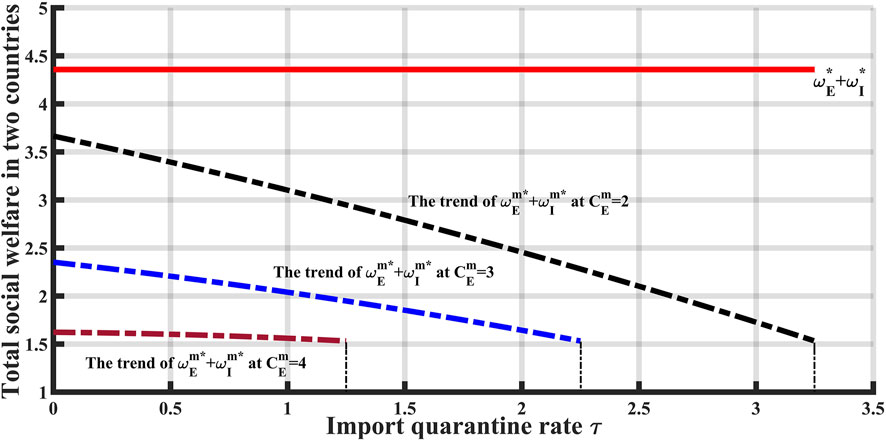

The trend in total social welfare ( ω E m ∗ + ω I m ∗ ) for both countries with τ and c E m is shown in Figure 3 .

FIGURE 3 . Trend of total social welfare in two countries. (Source: Simulation data for numerical calculations).

The horizontal line in Figure 3 is the sum of social welfare in the absence of the pandemic, which is independent of τ and c E m . The three curves show the change of the total of social welfare of the two countries with τ when c E m = 2,3,4 , and the curves show a decreasing trend. Affected by the pandemic, the social welfare of both countries are greatly reduced, and the greater the c E m , the more social welfare reduced; It can be seen from this that on the one hand, exporting countries should actively take measures to restore production capacity as soon as possible and reduce the cost of enterprises in the face of the pandemic; Social welfare has had a negative impact on the normal trade and economy of the two countries. The importing country should abandon trade protection and proceed from the overall situation of the trade between the two countries to jointly deal with the pandemic and achieve a win-win situation.

The government should be fully aware of the long-term nature and complexity of the game between the two countries and should respond to the WTO-compliant import quarantine fees imposed by the importing countries with a normal heart, and establish an early warning and response mechanism promptly, with the relevant subsidy policies for exporters. Both the governments and enterprises must actively negotiate with relevant governments and enterprises from both domestic and international perspectives and take the initiative to bear the impact of the pandemic on domestic and foreign trade.

In the face of the pandemic, exporting countries must first control the spread of the pandemic to reduce the costs of their enterprises. The tax exemption method or lowering export tax rate is a desirable fiscal policy to prevent enterprises from breaking their capital chains and help them smoothly overcome the hard times. Controlling the spread of the pandemic and subsidizing enterprises are effective means for exporting countries to restore the economy. However, it should not be overlooked that exporting countries make every effort to subsidize export enterprises, which will lead to unfair trade competition in the markets of importing countries, i.e., low-price competition of products, which reduces the profits of enterprises in exporting countries and reduces the profits of enterprises in importing countries, which is not conducive to the sustainable development of economy and trade.

The reasonable increase in import quarantine fees imposed by importing countries is conducive to enhancing the market competitiveness of their enterprises. However, when the importing country imposes higher import inspection and quarantine fees, not only seriously undermines the social welfare of the exporting country, bringing the possibility of trade friction between the two countries and promoting the increase in the price of products on the domestic market. Consumer surplus is reduced, which counterproductively reduces the country’s social welfare and is not conducive to the upgrading and industrial restructuring of domestic enterprises themselves. Therefore, the importing country should impose lower import quarantine fees to promote their social welfare and corporate profits. Importing countries should take other positive trade measures and exporting countries should cooperate fully to achieve a win-win situation.

When the pandemic comes, all countries should abandon trade protection, eliminate trade barriers, unblock trade channels, reasonably build stable supply chains and industrial chains, and commit to developing an equal, balanced, mutually beneficial and win-win trade partnership. Both exporting and importing countries must establish subsidies and import quarantine taxes that align with their own national conditions. On the one hand, they can promote healthy competition in the consumer market, and on the other hand, they must jointly respond to the negative impact of the pandemic on the economies of both countries. The two countries should actively conduct in-depth diplomatic consultations on the impact of the pandemic, promote the signing of bilateral border health and quarantine cooperation documents, and avoid the deterioration of trade relations and escalation of trade frictions caused by the pandemic. All countries should focus on long-term trade cooperation, adhere to the deeply intertwined model of mutually beneficial cooperation, clearly express their attitude and position to work together to overcome the pandemic, and resolutely oppose unilateral trade protection.

The research further enriches bilateral trade strategies’ theoretical connotation and practice under the pandemic. We only consider the situation of international duopoly competition. Still, the motive involving government intervention in the import and export of enterprises has always existed in the situation of multi-oligopoly competition. In particular, when the number of enterprises participating in international competition is more than one, the exporting country needs to consider the actual situation and negotiating power of each enterprise in formulating subsidy policies and balancing the competition effect among various enterprises. In addition, we only studied the pandemic situation in the exporting country and did not consider the pandemic situation in the importing country, nor did we consider the information asymmetry between enterprises and enterprises and between enterprises and governments. As future research, our model can be extended to multi-oligopoly competition while considering the asymmetry between firms and governments, making the model more realistic and challenging. Finally, the model is based on static decision-making, and we can also extend it to a dynamic decision-making model, that is, to study and analyze the evolution of import and export strategies over time. These deficiencies are left for future research to address.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

WT issued the idea and design for the research. JH and JL analyzed the model and drafted the manuscript. GR and FM revised the manuscript along with other authors.

This research was supported by Tianjin Research Innovation Project for Postgraduate Students (2021YJSS278). Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R260), Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Andoni, M., Robu, V., Couraud, B., Fruh, W.-G., Norbu, S., and Flynn, D. (2021). Analysis of Strategic Renewable Energy, Grid and Storage Capacity Investments via Stackelberg-Cournot Modelling. IEEE Access 9, 37752–37771. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3062981

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baldwin, R., and Di Mauro, B. W. (2020). Economics in the Time of COVID-19 . London: Centre for Economic Policy Research Press .

Google Scholar

Du, J., and Wang, B. (2018). Evolution of Global Cooperation in Multi-Level Threshold Public Goods Games with Income Redistribution. Front. Phys. 6, 67. doi:10.3389/fphy.2018.00067

Duan, H., Wang, S., and Yang, C. (2020). Coronavirus: Limit Short-Term Economic Damage. Nature 578 (7796), 578515–515. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00522-6

Ferreira, F. A., and Ferreira, F. (2009). Maximum-revenue Tariff under Bertrand Duopoly with Unknown Costs. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulation 14 (9-10), 3498–3502. doi:10.1016/j.cnsns.2009.01.026

Irfan, M., Razzaq, A., Suksatan, W., Sharif, A., Madurai Elavarasan, R., Yang, C., Hao, Y., and Rauf, A. (2022). Asymmetric Impact of Temperature on COVID-19 Spread in India: Evidence from Quantile-On-Quantile Regression Approach. J. Therm. Biol. 104, 103101. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103101

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Khan, S. A. R., Razzaq, A., Yu, Z., Shah, A., Sharif, A., and Janjua, L. (2021). Disruption in Food Supply Chain and Undernourishment Challenges: An Empirical Study in the Context of Asian Countries. Socio-Economic Plann. Sci. , 101033. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2021.101033

Lee, D.-S., and Kennedy, P. L. (2006). A Political Economic Analysis of U.S. Rice Export Programs to Japan and South Korea: A Game‐Theoretic Approach. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 88 (2), 420–431. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8276.2006.00868.x

Liang, W., Wu, D., and Guo, M. (2019). Discussion on the Establishment and Improvement of the Emergency Plan System for Nursing Emergencies in Public Health Events. Chin. J. Control. Endemic Dis. 34 (5), 548–549.

Mizuno, T., and Takauchi, K. (2020). Optimal export Policy with Upstream price Competition. Manchester Sch. 88 (2), 324–348. doi:10.1111/manc.12278

Razzaq, A., Sharif, A., Aziz, N., Irfan, M., and Jermsittiparsert, K. (2020). Asymmetric Link between Environmental Pollution and COVID-19 in the Top Ten Affected States of US: A Novel Estimations from Quantile-On-Quantile Approach. Environ. Res. 191, 110189. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.110189

Shahzad, F., Yannan, D., Kamran, H. W., Suksatan, W., Nik Hashim, N. A. A., and Razzaq, A. (2021). Outbreak of Epidemic Diseases and Stock Returns: an Event Study of Emerging Economy. Econ. Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja , 1–20. doi:10.1080/1331677x.2021.1941179

Shen, G. B. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on China’s Trade and Employment and Related Countermeasures. J. Shanghai Univ. Int. Business Econ. 27 (2), 16–25. doi:10.16060/j.cnki.issn2095-8072.2020.02.002

Sun, M., Wu, D., and Shi, J. F. (2014). Policies Change Related to Public Health Emergency Disposal in China: From 2003 to 2013. Chin. J. Health Pol. 7 (7), 24–29. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2014.07.004

Tang, W., Li, H., and Cai, K. (2020). Optimising the Credit Term Decisions in a Dual-Channel Supply Chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59 (14), 4324–4341. doi:10.1080/00207543.2020.1762018

Tang, W., Li, H., and Chen, J. (2021). Optimizing Carbon Taxation Target and Level: Enterprises, Consumers, or Both? J. Clean. Prod. 282, 124515. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124515

Wang, T. S., and Zhang, Q. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on China’s Foreign Trade Enterprises and Countermeasures. Econ. Rev. J. 3, 23–29. doi:10.16528/j.cnki.22-1054/f.202003023

Xi, H., and Zang, L. Q. (2020). Research on Fundamental Problems and Key Nodes of Emergency Management of Public Health Emergencies. Acad. Res. 4, 1–7+177. doi:10.1155/2022/7513461

Xie, S. X., Liu, P. D., and Wang, X. S. (2018). Price Competition, Strategic Trade Policy Adjustment and Firms’ Export Mode Choicing. Econ. Res. J. 10, 127–141.

Xie, S. X., Shi, H. M., and Zang, M. X. (2016). The Bargaining Power and Strategic Trade Policies. The J. World Economy 7, 3–23. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023478

Xuefeng, Z., Razzaq, A., Gokmenoglu, K. K., and Rehman, F. U. (2021). Time Varying Interdependency between COVID-19, Tourism Market, Oil Prices, and Sustainable Climate in United States: Evidence from advance Wavelet Coherence Approach. Econ. Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja , 1–23. doi:10.1080/1331677x.2021.1992642

Yang, H., Wu, Y., Yao, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, S., Xie, L., et al. (2021). How to Reach a Regional Cooperation Mechanism to Deal with the Epidemic: An Analysis from the Game Theory Perspective. Front. Public Health 9, 738184. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.738184

Yang, S. H., and Wei, S. D. (2013). A Game Analysis on the Effects of Carbon Tariff on China and the United States. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. S2, 634–640. doi:10.16381/j.cnki.issn1003-207x.2013.s2.021

Yu, Z., Razzaq, A., Rehman, A., Shah, A., Jameel, K., and Mor, R. S. (2021). Disruption in Global Supply Chain and Socio-Economic Shocks: a Lesson from COVID-19 for Sustainable Production and Consumption. Operations Manag. Res. , 1–16. doi:10.1007/s12063-021-00179-y

Zhang, X. H. (2020). The Impact of Novel Coronavirus Outbreak on Small and Micro Enterprises in China and Countermeasures. China Business And Market 34 (3), 26–34. doi:10.14089/j.cnki.cn11-3664/f.2020.03.004

Keywords: COVID-19, stackelberg game, import and export, import quarantine fee, strategies

Citation: Tang W, Hu J, Reivan Ortiz GG, Mabrouk F and Li J (2022) Research on the Impact of COVID-19 on Import and Export Strategies. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:891780. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.891780

Received: 08 March 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2022; Published: 26 April 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Tang, Hu, Reivan Ortiz, Mabrouk and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenguang Tang, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Advertisement

Trade and growth in developing countries: the role of export composition, import composition and export diversification

- Published: 03 August 2020

- Volume 54 , pages 919–941, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Carlos A. Carrasco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5439-4960 1 &

- Edgar Demetrio Tovar-García 2

2942 Accesses

42 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

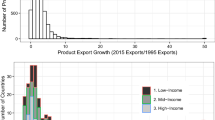

We investigate the trade-economic growth nexus in developing countries considering the structure of the external sector. The economic literature has examined the effects on growth of export composition, export diversification and import composition, individually. We add to this discussion by jointly evaluating the role of these three factors in the trade-economic growth nexus. The assessment of the structure of the external sector allows identifying the features that improve the trade-economic growth nexus with relevant economic policy implications for developing countries. Using a sample of 19 developing countries and dynamic panel data models, we found that export composition and export diversification are insignificant. By contrast, the domestic content of exports, the share of high-tech imports and capital goods imports are positively associated with economic growth. Consequently, developing countries growth benefits from high-tech and capital goods imports, and potentially, from the development of an industrial policy able to boost the domestic production of inputs for the exporting sector.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source : World Development Indicators, World Bank and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-Stats), IMF Statistics

Similar content being viewed by others

Import Substitution and Export-Led Growth

Export growth drivers and economic development

Export specialization, trade liberalization and economic growth: a synthetic control analysis

Although the positive role of high-tech intensity goods trade in export performance, productivity and economic growth is recognized in several empirical works, it is a matter of study the definition and measurement of high-tech goods and industries. While this is an interesting subject, it falls outside the scope of this paper. In this paper, we follow the updated OECD classification based on the proposal by Hatzichronoglou ( 1997 ). For a discussion on this regard, see Hatzichronoglou ( 1997 ), Carroll et al. ( 2000 ), Peneder ( 2003 ) and Srholec ( 2007 ).

We include the share of 14 export industries according to OECD classification to compute the Herfindahl–Hirschman index: agriculture, forestry and fishing; mining and quarrying; food products, beverages and tobacco; textiles, wearing apparel, leather and related products; paper and printing; chemicals, rubber, plastics and fuel products; other nonmetallic mineral products; basic metals and fabricated metal products, except machinery and equipment; machinery and equipment; transport equipment; furniture, other manufacturing; electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; other activities; total waste.

Abdi H, Williams LJ (2010) Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat 2:433–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.101

Article Google Scholar

Aditya A, Acharyya R (2013) Export diversification, composition, and economic growth: evidence from cross-country analysis. J Int Trade Econ Dev 22:959–992. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2011.619009

Agosin MR (2008) Export diversification and growth in emerging economies. CEPAL Rev 97:115–131

Google Scholar

Agosin MR, Alvarez R, Bravo-Ortega C (2012) Determinants of export diversification around the world: 1962–2000. World Econ 35:295–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2011.01395.x

Al-Marhubi F (2000) Export diversification and growth: an empirical investigation. Appl Econ Lett 7:559–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850050059005

Amir-ud-Din R, Usman M, Abbas F, Javed SA (2019) Human versus physical capital: issues of accumulation, interaction and endogeneity. Econ Chang Restruct 52:351–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-017-9225-2

Amurgo-Pacheco A, Pierola MD (2008) Patterns of export diversification in developing countries: intensive and extensive margins

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–297

Awokuse TO (2008) Trade openness and economic growth: is growth export-led or import-led? Appl Econ 40:161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600749490

Banga K (2016) Impact of global value chains on employment in India. J Econ Integr 31:631–673. https://doi.org/10.11130/jei.2016.31.3.631

Barro RJ (1999) Notes on growth accounting. J Econ Growth 1:119–137

Blanchard EJ, Olney WW (2017) Globalization and human capital investment: export composition drives educational attainment. J Int Econ 106:165–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.03.004

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87:115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

Bravo-Ortega C, Benavente JM, González Á (2014) Innovation, exports, and productivity: learning and self-selection in Chile. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 50:68–95. https://doi.org/10.2753/REE1540-496X5001S105

Cadot O, Carrere C, Strauss-kahn V (2011) Export diversification: what’s behind the hump? Rev ofEconomics Stat 93:590–605

Cárdenas G, Suárez E, Romero H, Fajardo E (2019) Composición de importaciones y actividad económica: El caso de Colombia. Espacios 40:24

Carrasco CA, Tovar-García ED (2019) Determinantes del Balance Comercial Bilateral de México: Ingreso, Tipo de Cambio y Composición de las Exportaciones. Rev Finanz y Política Económica 11:1

Carroll P, Pol E, Robertson PL (2000) Classification of industries by level of technology: an appraisal and some implications. Prometh Crit Stud Innov 18:417–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020020008523

Caselli F, Wilson DJ (2004) Importing technology. J Monet Econ 51:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2003.07.004

Del Prete D, Giovannetti G, Marvasi E (2017) Global value chains participation and productivity gains for North African firms. Rev World Econ 153:675–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0292-2

Dennis A, Shepherd B (2011) Trade facilitation and export diversification. World Econ 34:101–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01303.x

Dollar D, Kraay A (2004) Trade, growth, and poverty. Econ J 114:F22–F49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2004.00186.x

Dornbusch R (1992) The case for trade liberalization in developing countries. J Econ Perspect 6:69–85. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.6.1.69

Dosi G, Roventini A, Russo E (2019) Endogenous growth and global divergence in a multi-country agent-based model. J Econ Dyn Control 101:101–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2019.02.005

Eaton J, Kortum S (2001) Trade in capital goods. Eur Econ Rev 45:1195–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(00)00103-3

Ekananda M, Parlinggoman DJ (2017) The role of high-tech exports and of foreign direct investments (FDI) on economic growth. Eur Res Stud J 20:194–212

Fagerberg J, Lundvall B-A, Srholec M (2018) Global value chains, national innovation systems and economic development. Eur J Dev Res. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-0180147-2

Foster-McGregor N, Kaulich F, Stehrer R (2015) Global value chains in Africa. Maastricht, The Netherlands

Fosu AK (1990) Export composition and the impact of exports on economic growth of developing economies. Econ Lett 34:67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(90)90183-2

Frankel JA, Romer D (1999) Does trade cause growth? Am Econ Rev 89:379–399. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.3.379

Fujii G (2000) El comercio exterior manufacturero y los límites al crecimiento económico de México. Comer Exter Noviembre 1:1008–1014

Fujii G, Candaudap E, Gaona C (2005) Exportaciones, industria maquiladora y crecimiento económico en México a partir de la década de los noventa. Investig Económica 64:125–156

Ghatak S, Milner C, Utkulu U (1997) Exports, export composition and growth: cointegration and causality evidence for Malaysia. Appl Econ 29:213–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368497327272

Glaeser EL, La-Porta R, Lopez-De-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2004) Do institutions cause growth? J Econ Growth 9:271–303

Grossman GM, Helpman E (1990) Trade, innovation, and growth. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 80:86–91

Grossman GM, Helpman E (1991) Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. Eur Econ Rev 35:517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(91)90153-A

Hagemejer J (2018) Trade and growth in the new member states: the role of global value chains. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 54:2630–2649. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1369878

Hagemejer J, Mućk J (2019) Export-led growth and its determinants: evidence from Central and Eastern European countries. World Econ 42:1994–2025. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12790

Haini H (2019) Examining the relationship between finance, institutions and economic growth: evidence from the ASEAN economies. Econ Chang Restruct. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-019-09257-5

Hatzichronoglou T (1997) Revision of the high-technology sector and product classification

Hausmann R, Hwang J, Rodrik D (2007) What you export matters. J Econ Growth 12:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-006-9009-4

Henn C, Papageorgiou C, Spatafora N (2013) Export quality in developing countries

Herrerias MJ, Orts V (2013) Capital goods imports and long-run growth: is the Chinese experience relevant to developing countries? J Policy Model 35:781–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2013.02.006

Herzer D, Nowak-Lehnmann DF (2006) What does export diversification do for growth? An econometric analysis. Appl Econ 38:1825–1838. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840500426983

Herzer D, Nowak-Lehmann F, Siliverstovs B (2006) Export-led growth in Chile: assessing the role of export composition in productivity growth. Dev Econ 44:306–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1049.2006.00019.x

Hesse H (2009) Export diversification and economic growth. In: Newfarmer R, Shaw W, Walkenhorst P (eds) Breaking into new markets: emerging lessons for export diversification. The World Bank, Washington, pp 55–80

Hirsch S, Lev B (1971) Sales stabilization through export diversification. Rev Econ Stat 53:270. https://doi.org/10.2307/1937971

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econom 115:53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7

International Monetary Fund (2014) Sustaining long-run growth and macroeconomic stability in low-income countries—The role of structural transformation and diversification

Johnson RC (2014) Five facts about value-added exports and implications for macroeconomics and trade research. J Econ Perspect 28:119–142. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.2.119

Kim D-H, Lin S-C, Suen Y-B (2016) Trade, growth and growth volatility: new panel evidence. Int Rev Econ Financ 45:384–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2016.07.006

Krueger A (1974) The political economy of the rent-seeking society. Am Econ Rev 64:291–303

Kummritz V (2015) Global value chains: benefiting the domestic economy?

Lee J-W (1995) Capital goods imports and long-run growth. J Dev Econ 48:91–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(95)00015-1

Lewer JJ (2002) International trade composition and medium-run growth: evidence of a causal relationship. Int Trade J 16:295–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853900290090809

Maddala GS, Wu S (1999) A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 61:631–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.0610s1631

Mankiw NG, Romer D, Weil DN (1992) A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Q J Econ 107:407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

Mazumdar J (1996) Do static gains from trade lead to medium-run growth? J Polit Econ 104:1328–1337. https://doi.org/10.1086/262062

Munir K, Javed Z (2018) Export composition and economic growth: evidence from South Asian countries. South Asian J Bus Stud 7:225–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-10-2017-0117

Mutreja P, Ravikumar B, Sposi M (2018) Capital goods trade, relative prices, and economic development. Rev Econ Dyn 27:101–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2017.11.003

Naito T (2017) An asymmetric Melitz model of trade and growth. Econ Lett 158:80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.06.016

Naudé W, Rossouw R (2011) Export diversification and economic performance: evidence from Brazil, China, India and South Africa. Econ Chang Restruct 44:99–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-010-9089-1

Palley TI (2012) The rise and fall of export-led growth. Investig Económica 71:141–161

Peneder M (2003) Industry classifications: aim, scope and techniques. J Ind Compet Trade 3:109–129. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025434721292

Pierola MD, Fernandes AM, Farole T (2018) The role of imports for exporter performance in Peru. World Econ 41:550–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12524

Pistoresi B, Rinaldi A (2012) Exports, imports and growth. Explor Econ Hist 49:241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2011.11.003

Raveh O, Reshef A (2016) Capital imports composition, complementarities, and the skill premium in developing countries. J Dev Econ 118:183–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.07.011

Rhoades SA (1993) The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. Fed Reserv Bull 79:188–189

Rodil-Marzábal O (2018) La cara oculta del comercio de México con Estados Unidos. Comer Exter 13:8–14

Romer PM (1986) Increasing returns and long-run growth. J Polit Econ 94:1002–1037

Romer PM (1994) The origins of endogenous growth. J Econ Perspect 8:3–22

Roodman D (2009) A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 71:135–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2008.00542.x

Sachs JD, Warner A (1995) Economic reform and the process of global integration. Brookings Pap Econ Act 1995:1–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534573

Santos-Paulino AU (2011) Trade specialization, export productivity and growth in Brazil, China, India, South Africa, and a cross section of countries. Econ Chang Restruct 44:75–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-010-9087-3

Saviotti PP, Frenken K (2008) Export variety and the economic performance of countries. J Evol Econ 18:201–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-007-0081-5

Saviotti PP, Pyka A (2013) The co-evolution of innovation, demand and growth. Econ Innov New Technol 22:461–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2013.768492

Sheridan BJ (2014) Manufacturing exports and growth: when is a developing country ready to transition from primary exports to manufacturing exports? J Macroecon 42:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2014.06.002

Solow RM (1956) A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q J Econ 70:65–94

Srholec M (2007) High-tech exports from developing countries: a symptom of technology spurts or statistical illusion? Rev World Econ 143:227–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-007-0106-z

Tovar-García ED (2018) Does the share of crude petroleum and natural gas in exports increase total exports? The Russian case. World Econ Int Relations 62:30–35. https://doi.org/10.20542/0131-2227-2018-62-6-30-35

Tovar-García ED, Carrasco CA (2019a) The balance of payments and Russian economic growth. HSE Econ J 23:524–541. https://doi.org/10.17323/1813-8691-2019-23-4-524-541

Tovar-García ED, Carrasco CA (2019b) Export and import composition as determinants of bilateral trade in goods: evidence from Russia. Post-Communist Econ 31:530–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2018.1557913

Toye J (2003) The Origins and Interpretation of the Prebisch-Singer Thesis. Hist Polit Econ 35:437–467. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182702-35-3-437

Turco AL (2012) Economic growth and the role of trade in intermediates. Econ Bull 32:1–20

Vogiatzoglou K (2019) Export composition and long-run economic growth impact: a cointegration analysis for ASEAN ‘Latecomer’ Economies. Margin J Appl Econ Res 13:168–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973801018812571

Wacziarg R, Welch KH (2008) Trade liberalization and growth: new evidence. World Bank Econ Rev 22:187–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhn007

Wierts P, Van Kerkhoff H, De Haan J (2014) Composition of exports and export performance of Eurozone countries. J Common Mark Stud 52:928–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12114

Download references

Acknowledgements

Comments from the Editor and two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Departamento de Economía, Universidad de Monterrey (UDEM), Av. Ignacio Morones Prieto 4500 Pte, 66238, San Pedro Garza García, N.L., Mexico

Carlos A. Carrasco

Universidad Panamericana, Escuela de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, Álvaro del Portillo 49, 45010, Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico

Edgar Demetrio Tovar-García

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carlos A. Carrasco .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Carrasco, C.A., Tovar-García, E.D. Trade and growth in developing countries: the role of export composition, import composition and export diversification. Econ Change Restruct 54 , 919–941 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-09291-8

Download citation

Received : 15 July 2019

Accepted : 27 July 2020

Published : 03 August 2020

Issue Date : November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-09291-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic growth

- Export composition

- Export diversification

- Import composition

- Developing countries

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Effects of COVID-19 on trade flows: Measuring their impact through government policy responses

Contributed equally to this work with: Javier Barbero, Juan José de Lucio, Ernesto Rodríguez-Crespo

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission, Seville, Andalucía, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Economic Structure and Development Economics, Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Department of Economic Structure and Development Economics, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- Javier Barbero,

- Juan José de Lucio,

- Ernesto Rodríguez-Crespo

- Published: October 13, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

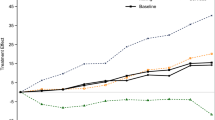

This paper examines the impact of COVID-19 on bilateral trade flows using a state-of-the-art gravity model of trade. Using the monthly trade data of 68 countries exporting across 222 destinations between January 2019 and October 2020, our results are threefold. First, we find a greater negative impact of COVID-19 on bilateral trade for those countries that were members of regional trade agreements before the pandemic. Second, we find that the impact of COVID-19 is negative and significant when we consider indicators related to governmental actions. Finally, this negative effect is more intense when exporter and importer country share identical income levels. In the latter case, the highest negative impact is found for exports between high-income countries.

Citation: Barbero J, de Lucio JJ, Rodríguez-Crespo E (2021) Effects of COVID-19 on trade flows: Measuring their impact through government policy responses. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0258356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258356

Editor: Stefan Cristian Gherghina, The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, ROMANIA

Received: April 12, 2021; Accepted: September 26, 2021; Published: October 13, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Barbero et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from UN Comtrade ( https://comtrade.un.org ), the Centre d'Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII) Gravity database ( http://www.cepii.fr/cepii/en/bdd_modele/presentation.asp?id=8 ) and from Our World in Data COVID-19 Git Hub repository ( https://github.com/owid/covid-19-data/tree/master/public/data ). The three datasets are publicly available for all researchers. Merging the three datasets and following the steps described in the “Model description and estimation strategy” section readers can replicate the results of this manuscript.

Funding: de Lucio and Rodríguez-Crespo thank financial support from Universidad de Alcalá de Henares (UAH) and Banco Santander through research project COVID-19 UAH 2019/00003/016/001/007. De Lucio also thanks financial support from Comunidad de Madrid and UAH (ref: EPU-INV/2020/006 and H2019/HUM5761).

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The world is facing an unexpected recession due to the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic in the global economy. In parallel with the consequences of the 2008–2009 crisis, international trade has once again collapsed. World trade volumes decreased by 21% between March and April 2020, while during the previous crisis the highest monthly drop was 18%, between September and October 2008. Cumulative export growth rate for the period December 2019– March 2020 was -7%, while for the period July 2008 –February 2009 it was -0,8%. The 2020 downturn was less prolonged than that caused by the latter crisis. Trade volumes in August 2020 only showed a 3% decrease compared to March 2020. The World Trade Organization (WTO) estimated that international merchandise trade volumes fell by 9.2% in 2020, a figure similar in magnitude to the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, although factors such as the economic context, the origins of the crisis and the transmission channels are deemed to be very distinct from the previous crisis [ 1 ].

Due to its rapid propagation, a proper evaluation of the economic impacts of COVID-19 crisis is not only desirable but challenging if the aim is to mitigate uncertainty [ 2 ]. The COVID-19 crisis has its origins in the policy measures adopted to combat the health crisis, while the 2008–2009 crisis had economic roots contingent on financially related issues. At the current time, the collapse of international trade has been driven by the voluntary and mandatory confinement measures imposed on world trade. We aim to analyse the impact of said confinement measures on trade. Estimating COVID-19 impacts on trade would shed light on the cost of confinement measures and the evolution and forecast of bilateral trade.

From an empirical point of view, we resort to [ 3 ], who use quarterly data for the period 2003–2005 in order to analyse the impact of the SARS epidemic on firms. They show that regions with higher transmission of SARS experienced lower import and export growth compared to those in the unaffected regions. The propagation of a virus resembles natural disasters, with both interpreted as external non-economic based shocks, the effects of which have been addressed already in the literature (e.g., [ 4 – 9 ]).

Another strand of the literature directly analyses the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on global trade in terms of the transmission mechanism of the shock: demand, supply and global supply chains. Some authors argue that demand factors have played an important role in explaining the shock [ 10 , 11 ] conclude that both shocks (demand and supply) are present in the crisis [ 1 ] highlight the role of global value chains in the transmission of shocks [ 12 ] focus on supply chain disruptions and reveal that those sectors with large exposure to intermediate goods imports from China contracted more than other sectors [ 13 ]. Focus on the role of global supply chains on the GDP growth for 64 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic and show that one quarter of the total downturn is due to global supply chains transmission. They also conclude that in general global supply chains, make countries more resilient to pandemic-induced contractions in labour supply. Finally, the collapse in trade can also be considered as a trade-induced effect caused by economic recessions (e.g., [ 14 – 16 ]) and may also be associated with the impact of COVID-19.

During the current wave of globalization, time lags in synchronizing business cycles between countries are reduced significantly in terms of the intensity of trade relationships [ 17 ]. Find that business cycle synchronization increases when countries trade more with each other [ 18 ]. Show that bilateral trade intensity has a sizeable positive, statistically significant, and robust impact on synchronization. These results are in line with [ 19 ], who finds that greater trade intensity increases business cycle synchronization, especially in country pairs with a free trade agreement and among industrial country pairs. Our paper provides prima facie evidence that this relationship also holds during pandemic-related trade shocks.

We contribute to the literature by integrating monthly data for a trade analysis of 68 countries, 31 of which are classified as high-income. We additionally focus on differential effects between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. This paper aims to shed light on the impact of COVID-19 on exports by means of an integrated approach for a significant number of countries, thereby avoiding an individual analysis of a single country or region that could potentially be affected by idiosyncratic shocks. Given the existence of substantial differences in trade performance and containment measures exhibited by countries and trade partners and attributable in part to their income, we also study whether the impact of COVID-19 on trade differs in terms of income levels. To the best of our knowledge, both questions, the integrated impact of confinement measures and the income related effects, remain unexplored in previous studies.

A proper analysis of ex-post trade impacts related to COVID-19 requires a suitable and fruitful methodology. Gravity models can be helpful in achieving this goal, since they have recently started to incorporate monthly trade data into the analyses, albeit with empirical evidence that is still scarce and far from conclusive [ 8 , 20 , 21 ]. At the same time, several methodological issues need to be resolved adequately when using gravity models [ 22 ]. Resorting to monthly data may pose several advantages in terms of accomplishing our research goals and exploiting the explanatory power exhibited by gravity models and monthly country confinement measures. First, the data reflect monthly variations and allow us to better capture any differential effects arising across countries. Second, annual trade data do not capture the short-run impact of shocks that occur very rapidly, something which a monthly time span can achieve. Monthly data can pick up any rapid movements associated with COVID-19 measures and allow for differential shocks in relation to months and countries. This is particularly relevant given the growing importance of nowcasting and short-term analysis techniques required nowadays for an understanding of world economy dynamics. Finally, monthly data can explain the relative importance of demand and supply shocks during the course of the trade crisis.

We collect monthly trade data for 68 countries ( S1 Table ), which exported to 222 destinations between January 2019 and October 2020. Using state-of-the-art estimation techniques for trade-related gravity models, our results are threefold. First, we reveal a negative impact of COVID-19 on trade that holds across specifications. Second, we obtain results that do not vary substantially when considering different governmental measures. Finally, our results show that the greatest negative COVID-19 impact occurs for exports within groups (high-income countries and low-middle-income countries), but not between groups. These findings are robust to different tests resulting from the introduction of lagging explanatory variables, alternative trade flows (exports vs imports as the dependent variable) or COVID-19 impact measures (independent variables such as stringency index or the number of reported deaths per million population).

Literature review on COVID-19 and trade

The specific literature covering the COVID-19 induced effects on trade can be catalogued as flourishing and burgeoning, but also as incipient and inconclusive at the current time. Some studies have addressed the impact of the health-related crisis on trade. The first strand of literature analyses the effects of previous pandemics by emphasizing asymmetric impacts across sectors. Using the quarterly transaction-level trade data of all Chinese firms in 2003 [ 3 ], estimate the effects of the first SARS pandemic on trade in that year. They find that (i) Chinese regions with a local transmission of SARS experienced a lower decline in trade margins, and (ii) the trade of more skilled and capital-intensive products was less affected by the pandemic.

Despite data being scarce, other studies focus on the current COVID-19 trade shock but are usually restricted to specific countries. For the case of Switzerland [ 23 ], combine weekly and monthly trade data, for the lockdown between mid-March and the end of July. They use goods information disaggregated by product and trade partner. They find that: (i) During lockdown Swiss trade fell 11% compared to the same period of 2019, and this trade shock proved more profound than the previous trade shock in 2009, (ii) contraction in Swiss exports seems to be correlated with the number of COVID-19 cases in importing countries, but at the same time, Swiss imports are related to the stringency of government measures in the exporter country (iii) for the case of products, only pharmaceutical and chemical products remained resilient to the trade shock and (iv) the pandemic negatively affected the demand and supply sides of foreign trade [ 24 ]. Use a gravity model and focus on exports from China for the period January 2019 to December 2020. They find a negative effect of COVID-19 on trade, but said effect is largely attenuated for medical goods and products that entail working from home.

For the case of Spain [ 10 ], find that for the period between January and July 2020, stringency in containment measures at the destination countries decreased Spanish exports, while imports did not succumb to such a sharp decline. Finally [ 25 ], extends the discussion of the Spanish case to analyse the impact of COVID-19 on trade in goods and services, corroborating the existence of a negative effect. He finds a more pronounced decline for trade in services, due to the importance of tourism in the Spanish economy.

Other studies have provided additional evidence by considering a larger sample of countries. Using monthly bilateral trade data of EU member states covering the period from June 2015 to May 2020 [ 20 ], use a gravity model framework to highlight the role of chain forward linkages for the transmission of Covid-19 demand shocks. They explain that when the pandemic spread and more prominent measures were taken, not only did demand decrease further, but labour supply shortage and production halted [ 21 ]. Find a negative impact of COVID-19 on trade growth for a sample of 28 countries and their most relevant trade partners. Their findings suggest that COVID-19 has affected sectoral trade growth negatively by decreasing countries’ participations in Global Value Chains from the beginning of the pandemic to June 2020 [ 26 ]. Analyse the impact of COVID-19 on trade for a larger sample of countries, focusing on export flows for 35 reporting countries and 250 partner countries between January and August in both 2019 and 2020. However, they restrict, their study exclusively to trade in medical goods and find that an increase in COVID-19 stringency leads to lower exports of medical products. Finally [ 27 ], use maritime trade shipping data from January to June 2020 for different countries, such as Australia, China, Germany, Malaysia, New Zealand, South Africa, United States, United Kingdom, and Vietnam. By applying the automatic identification system methodology to observational data, they obtain pronounced declines in trade, albeit the effect is different for each country.