What do you mean by organizational structure? Acknowledging and harmonizing differences and commonalities in three prominent perspectives

- Point of View

- Open access

- Published: 11 October 2023

- Volume 13 , pages 1–11, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Daniel Albert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3888-1643 1

7923 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The organizational design literature stresses the importance of organizational structure to understand strategic change, performance, and innovation. However, prior studies diverge regarding the conceptualizations and operationalizations of structure. Organizational structure has been studied as an (1) arrangement of activities, (2) representation of decision-making, and (3) legal entities. In this point-of-view paper, the three prominent perspectives of organizational structure are discussed in terms of their commonalities, differences, and the need to study their relationship more thoroughly. Future research may not only wish to integrate these dimensions but also be more vocal about what type of organization structure is studied and why.

Similar content being viewed by others

Organization Theory

Organizations: Theoretical Debates and the Scope of Organizational Theory

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An important area of research in the organization design literature concerns the role of structure. Early research, including work by Chandler ( 1962 , 1991 ) and Burgelman ( 1983 ), has studied how strategy execution depends on a firm’s structure, and how that structure can influence future strategies. Moreover, prior work has explored organizational structure and its connection to strategic change (Gulati and Puranam 2009 ), performance (Csaszar 2012 ; Lee 2022 ), innovation (Eklund 2022 ; Keum and See 2017 ) and internal power dynamics (Bidwell 2012 ; Pfeffer 1981 ), among others.

What is surprising is the divergence in understanding what constitutes and defines organizational structure. This becomes particularly apparent when considering how structure has often been operationalized in prior studies. While there are a variety of conceptual and empirical approaches to organizational structure, this point of view paper focuses on three particularly prominent perspectives. Scholars of one stream of operationalization have argued that structure is how business activities are grouped and assessed in the form of distinct business units (or divisions) (Karim 2006 ; Mintzberg 1979 ), which may represent a company’s operating segments for internal and external reporting (Albert 2018 ). In another stream of operationalization, scholars argue that structure is inherent in the organizational chart, specifically, the chain of command and the allocation of decision-making responsibilities. Often, a simple yet powerful proxy has been to consider the roles assigned to the top management team members (Girod and Whittington 2015 ). Finally, a third type of operationalization of structure is the composition and arrangement of legal entities (Bethel and Liebeskind 1998 ; Zhou 2013 ), specifically, discrete subsidiaries constituting an organization’s business activities. This may be the most consequential understanding of structure as it relates to the containment of legal responsibilities.

These three perspectives overlap in some cases but may also characterize organizational structure differently in important ways. In a clear-cut case, a firm may consist of a top management team that perfectly reflects its business divisions and units, reported by consolidated but legally distinct entities. However, when examining the financial filings of different corporations, a different picture emerges as such clean alignment is often not the case. Not only are well-studied differences in the corporation's legal form (such as holding versus integrated) present, but top management responsibilities and reporting of business divisions often show that structure is indeed a multi-dimensional phenomenon in organizations.

To illustrate how different perspectives may lead to varying conclusions about organizational structure, two companies, the financial service firm Citigroup and the automotive company Ford Motor, are briefly discussed with respect to each perspective. Both Citigroup and Ford Motor are interesting cases, as they are large organizations with diversified business operations across various industry segments and a presence in multiple geographical markets. This complexity in business operations underscores the necessity of an organizational structure to implement and execute the firms' respective strategies.

The objective of this point of view is to emphasize and discuss the co-existence of fundamentally different measures and their underlying assumptions of organizational structure. These three perspectives highlight different aspects of organizational structure and can help reveal important nuances idiosyncratic to specific organizations. That is, complementing one perspective with one or two other perspectives can paint a more holistic picture of firm-specific structural designs. The “arrangement of activities” perspective provides generally a measure that captures sources of value creation, that is, the groupings of economic activities and knowledge. The “decision making representation” perspective provides generally a measure of hierarchical allocation of decision rights and has been likened to the level of centralization, that is, which responsibilities are specifically assigned to the highest level of decision-making. The “legal entities” perspective often captures decentralization as "truly" autonomous activities that can render integration more difficult and, therefore, imposes greater decentralization among such units.

A follow-up goal of this point of view paper is to discuss the implications and future research opportunities of clearly distinguishing between these perspectives in organizational design studies. A completely new area of research constitutes the inquiry of the relationships between these perspectives and whether and when alignment between the perspectives is enhancing or hindering performance, innovation, and strategic change. It is important to note that this point of view paper is not meant to provide an exhaustive list of perspectives of organizational structure, but to spark a constructive discussion around the theoretical and operational differences and commonalities between the arguably most prominent perspectives. Additional perspectives of organizational structure are discussed in the limitations section.

Three perspectives of structure

Structure as arrangement of activities.

This perspective suggests that groups of economic activities, managed and reviewed together, make up departments, units, and divisions that form the organizational structure (Joseph and Gaba 2020 ; Mintzberg 1979 ; Puranam and Vanneste 2016 ). In the middle of the twentieth century, Chandler ( 1962 ) observed that large American corporations not only diversified into a greater number of different business activities but also started to organize business activities into separately managed divisions, which are typically overseen by a corporate center unit. The organization of activities into compartments is often nested, that is, activities within a given compartment are further organized into subunits and so on. In a more general sense, such compartmentalization constitutes the division of labor (or specialization) in an organization, which can be organized along various dimensions. The most prevalent dimensions along which activities are organized into units include customer segments, products, geography, and functional domains, such as research and development, marketing, and sales activities (Puranam and Vanneste 2016 ).

The way activities are organized has been often related to archetypical designs, such as a more homogenous organization that is organized along functions and multi-divisional corporations that are more heterogenous in the activities making up business divisions (e.g., Raveendran 2020 ). The corporate center is often considered as a distinct unit of activities that holds the design rights of the organization, allowing it to organize these activities (Puranam 2018 ). The center may also play a coordinating role in the management of interdependencies between divisions to ensure alignment with corporate-level goals (Lawrence and Lorsch 1967 ) and foster value creation (Foss 1997 ).

Scholars of this perspective have studied how the arrangement of activities into compartments is associated with the propensity and type of reorganization (e.g., Karim 2006 ; Raveendran 2020 ), as well as its association with innovation outcomes (e.g., Karim and Kaul 2014 ). These two outcomes of interest are closely related, as compartments consist of employees and resources that constitute a source of knowledge that may be rearranged or combined with other units to address a (changing) market in novel and more efficient ways. Hence, this perspective may help to understand the sources of performance and innovation.

Illustration of arrangement of activities perspective

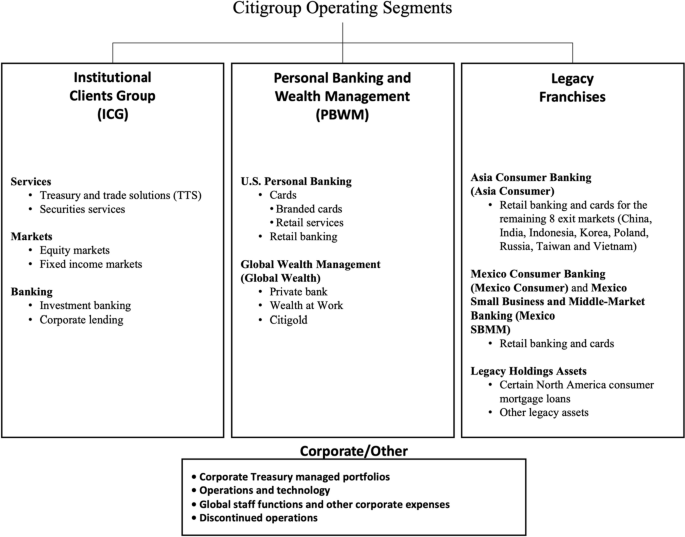

Figure 1 shows Citigroup’s operating business segments, which are in line with accounting regulations that require businesses to disclose operations in the way in which activities are managed internally and held accountable for cost and revenues (see Financial Accounting Standards No. 131). Accordingly, Citigroup operates three business segments, “Institutional Clients Group (ICG)”, “Personal Banking and Wealth Management (PBWM)” and “Legacy Franchises”, which are predominantly groupings of economic activities based on customer segments (i.e., institutional clients, private clients, and consumer clients). These groupings encompass various activities around this customer segment and the relevant product offerings. For example, the division Personal Banking encompasses activities for retail clients, such as Citibank’s physical retail network and online banking as well as private wealth operations for high-net-worth individuals. The respective segments may be understood as the organization’s business divisions, whereas further, nested, groupings exist within these divisions (e.g., U.S. Personal Banking constitutes a subunit with further subgroupings into Cards and Retail Banking operations). Supporting activities and operations that are not part of one of the three divisions are managed by the corporate center unit.

Citigroup’s operating business segments. This figure is the author’s own drawing but entirely based on Citigroup’s 2022 10-K report (page 2)

In Table 1 , the operating business segments are shown for the automotive company Ford. Accordingly, Ford operates six main segments (and one reconciliation of debt segment), “Ford Blue”, “Ford Model e”, “Ford Pro”, “Ford Next”, “Ford Credit”, and “Corporate Other”. These groupings encompass various product and customer segment activities, such as the “Ford Blue” legacy business of internal combustion engine automotives, under the Ford and Lincoln brands. Electric vehicle-related activities are grouped under “Ford Model e”, whereas “Ford Pro” groups activities to address corporate clients who seek to optimize and maintain fleets. Noteworthy is also the segment “Ford Next”, which is a grouping of investment activities into emerging business models. While these segments (i.e., divisions) encompass various activities, information is limited with respect to any nested groupings within these segments (or a potential lack thereof).

Structure as decision making representation

This perspective suggests that the job roles in the top management team (TMT) are reflective of the organizational structure, as executives are charged to oversee certain activities (Girod and Whittington 2015 ; Guadalupe et al. 2013 ). At first glance, this understanding is fairly similar to that of the arrangement of activities. At a closer look, however, the TMT structure perspective is more indicative of an information processing perspective. At the center of the information processing perspective lies hierarchy as a mechanism to cope with information uncertainty and resolve conflicts (Galbraith 1974 ). Moreover, information processing has long been considered as the way in which key decision-makers can ensure coordination and integration of units (Joseph and Gaba 2020 ). That is, the top management roles may in fact extend beyond the formal task structure and include the reintegration and coordination of activities more broadly.

The assignment of decision-making responsibilities can reveal how the organization “thinks” about interdependencies, such as the need to coordinate resources, the potential to leverage synergies and so forth. For example, roles that largely define autonomous areas of business allow managers to make decisions more independently from one another. In contrast, roles that are focused on dedicated functions, such as research and development, marketing, and finance often require greater coordination among managers (e.g., Hambrick et al. 2015 ). Hence, the decision-making representations in the top management team may be understood as a hierarchy mechanism to manage and even create interdependencies between activities. A case in point is the deliberate assignment of creating synergies between otherwise standalone units, for example, in the form of executives holding multiple roles that span several divisions.

While the assignment of decision-making responsibilities clearly relates to efforts of coordination and integration, it can also explain the emergence of internal power and politics dynamics (Cyert and March 1963 , Pfeffer 1981 ). For example, Romanelli and Tushman 9/14/2023 7:00:00 PM suggest that top management turnover is a measure of power dynamics in organizations and treat this as entirely distinct from organizational structure. Moreover, the upper echelons perspective has proposed that organizational choice and strategic outcomes are, at least in part, a direct reflection of the backgrounds of the leadership's individuals (Hambrick and Mason 1984 ), which suggests that design choices, such as organizational structure are decided under the auspice of the very same individuals (Puranam 2018 ) that researchers have used as a proxy to measure organizational structure. This emphasizes the importance of considering the TMT as a structure of decision-making representation rather than a measure of division of labor.

Perhaps it is this representational role of the TMT as a potential liaison between activity arrangements and decision-making, which Gaba and Joseph ( 2020 ) discuss as information processing, that has led some of the prior research argue that structure influences how decisions come about. Accordingly, decisions of reorganization and internal resource allocation are the result of a political negotiation process (Albert 2018 ; Bidwell 2012 ; Keum 2023 ; Pfeffer 1981 ; Pfeffer and Salancik 1974 ). Hence, this perspective may help understand the role of structure as a process that shapes decisions (Burgelman 1983 ).

Illustration of decision-making representation perspective

Table 2 shows Citigroup’s executive leadership team with each member’s specific job title that reflects the decision-making responsibilities. The team is made up of executives responsible for specific business divisions (e.g., one member carries the title CEO of Legacy Franchises), some members oversee particular geographical regions (e.g., one member carries the title CEO of Latin America), other members represent specific subsidiaries (e.g., one member carries the title CEO of Citibank N.A.), and again others are in charge of corporate functions (e.g., one member carries the title Head of Human Resources).

Table 3 shows Ford’s executive leadership team. The team is made up of executives responsible for business divisions, such as “President Ford Blue”, “CEO, Ford Pro” and “CEO, Ford Next”. In addition, executives represent particular activities of these divisions, such as “Chief Customer Officer, Ford Model e” and “Chief Customer Experience Officer, Ford Blue”. Similar to Citigroup, at Ford executives also represent geographical activities and various functional activities. Moreover, one executive represents a legal entity (Ford Next LLC), which is also a business segment (activity grouping).

Structure as legal entities

This perspective suggests that structure is delineated by legal boundaries, such as discrete subsidiaries that make up an organization’s operating units. This may constitute the most consequential understanding of structure as it relates to containment of legal responsibilities.

Thus, empirical studies have operationalized legal entities as a proxy for divisionalization in organizations (Argyres 1996 ; Zhou 2013 ) and degree of decentralization of research and development responsibilities (Arora et al. 2014 ). The way organizations are legally organized may be motivated by liability concerns, tax advantages, shareholder voting rights, as well as international law and compliance consideration (Bethel and Liebeskind 1998 ). Nevertheless, organizing into legally separate units can have important consequences for the management of the organization, such as limited economies of scope (see ibid.). For example, Monteiro et al. ( 2008 ) describe how subsidiaries in multinational corporations can become “isolated” from knowledge sharing with the rest of the organization. This isolation from intra-firm knowledge flows leads these subsidiaries to more likely underperform compared to less isolated subsidiaries.

It is important to note that legal structure is not always at the discretion of the organization. For example, the financial and economic crisis of 2007/8 has led legislators in some countries to introduce laws that require system-relevant banks to organize certain activities and assets into separate legal entities that contain losses and allow quicker resolvability in case the government decides to step in and take ownership stakes of affected units (Reuters 2014 ).

Legal structures, specifically in the context of multi-national organizations, have been studied with respect to decentralized decision-making, local market adaptation, and dynamics between subsidiaries and the headquarters (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008 ). Another aspect of studying legal entities in organizational design relates to internal reorganization. Legally separated activities are not only more straightforward to evaluate (i.e., greater transparency) as they typically maintain their own balance sheets and income statements, but they may also be easier to divest or spin-off, which provides the organization with greater flexibility. For example, the legal reorganization of Google into Alphabet in 2015 legally separated Google’s activities from all its “other bets”, which were run as their own legal organizations, with the goal for greater transparency and accountability (Zenger 2015 ). Moreover, the separation of activities into legal entities may also affect how easy or difficult it is for the organization to endorse cross-unit collaboration and execute internal reorganization without changing legal forms. Coordination cost between separate legal entities are greater, as more formal and legally binding contracts may need to be set.

Illustration of legal entities perspective

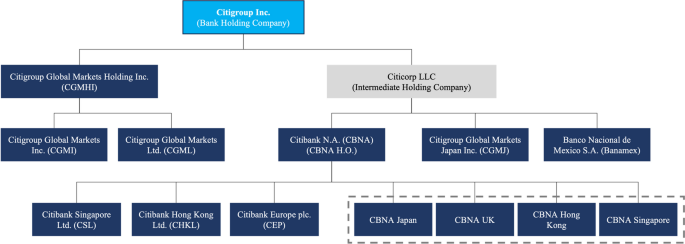

Figure 2 shows Citigroup’s legal structure. Accordingly, the organization is at the highest level a Bank Holding Company, which legally owns two (intermediate) holding entities, “Citigroup Global Markets Holdings Inc.” and “Citicorp LLC”. Each of these two entities owns additional subsidiaries, which are largely organized by region (these may hold additional subsidiaries). This structure is quite different from Citigroup’s management of operating activities as none of the business divisions is reflected in the legal structure.

Citigroup material legal entities. This figure is the author’s own drawing and a slight adaptation rom Citigroup’s publicly available presentation material via https://www.citigroup.com/rcs/citigpa/akpublic/storage/public/corp_struct.pdf , accessed on March 23, 2023. The dark blue boxed refer to operating material legal entities. The four boxes that are within the grey dashed rectangle are branches of Citibank N.A

Table 4 shows a list of legal entities reported by Ford in its annual report. Many of these subsidiaries are focused on regional activities and/or credit-related activities, which may be due to regulatory requirements of operating consumer financing activities. The legal entity Ford Next LLC is also its own business segment (i.e., an arrangement of activities reported as a managed division) and directly represented in the executive team. The Ford example does not provide much detail on the exact ownership structure among subsidiaries, which generally is indicative of a legal hierarchical structure of the respective legal entities. However, Ford European Holdings Inc. appears to own European subsidiaries, such as Ford Deutschland Holding GmbH, which in turn is the legal entity that owns subsidiaries in Germany and so on.

A path forward

The study of the commonalities , differences , and relationships between the three perspectives of organization structure—i.e., structure as arrangement of activities, decision-making representation, and legal entities—offers great potential for the field of organizational design. Previous research has often focused on one of these dimensions at a time to study organizational structure, but each perspective plays an important role in organizing and influencing decision-making.

Commonalities

All three perspectives share central ideas of organizational design. First, there is the notion that tasks are grouped and kept separate . The arrangement of activities perspective suggests that economic processes are managed and carried out together when these influence one another. Thus, this perspective stresses the grouping of tasks most forcefully of all the perspectives. However, the two other lines of research also reflect groupings of tasks. The decision-making representation perspective considers job titles and decision-making authority assigned to distinct members of the executive team to generally be related to how tasks are structured. Decision makers, therefore, oversee a particular task environment. The legal entity perspective proposes legal boundaries as delineations of responsibility and accountability. That is, legal separation and containment of financial accountability constitute somewhat binding modularity.

The three views also embrace the concept of hierarchy , albeit manifested differently. The arrangement of activities captures hierarchy by stressing that activity groups (i.e., units) can be nested, that is, a division is made up of several sub-units with own task responsibilities. Hierarchy in decision-making representation is captured by reporting lines and may be more focused on hierarchy as a means of conflict resolution and the diffusion of top-down ideas. The legal entity view shares similarity with the arrangement of activities perspective in that nested structures of subsidiaries can exist, but the “mechanism” of hierarchy is the ownership structure.

Differences

While the three perspectives have obvious similarities and overlap—after all, that is why scholars rely on one or the other perspectives to proxy organizational structure—these perspectives also capture distinct elements and, therefore, draw attention to different theoretical aspects of organization structure. The arrangement of activities perspective draws attention to the locus of value creation and innovation associated with structure. The grouping of activities influences whether synergies can be realized, goals achieved more quickly (Raveendran 2020 ) and whether knowledge can be recombined to seize innovation opportunities (Karim and Kaul 2014 ). The representation of decision-making perspectives draws attention to the top management team as structural authority to resolve conflicts between lower-level decision makers, and lobby for distinct operating activities in the organization. Moreover, top management plays a crucial role in the restructuring of the arrangement of activities and decisions with respect to changing the composition of legal entities. For example, political power of executives has been argued and shown to affect division reorganization decisions (Albert 2018 ) and allocation decisions of internal non-financial resources (Keum 2023 ). Finally, the legal entities perspective draws attention to structure as legal accountability and draws a sharp line between what is truly separate and what is more ‘loosely’ integrated. Consequently, arranging activities as legally separate entities often requires more costly coordination measures, such as formal contracts.

Theoretical and empirical questions around these differences may investigate the following claims.

A research focus on organizational structure as arrangement of activities may be of particular interest for the aim of understanding performance and innovation outcomes as economic activities are directly related to the process of value creation.

A research focus on organizational structure as decision-making representation may be of particular interest for the aim of understanding how strategic goals are formed, with respect to change and associated corporate reorganizations.

A research focus on organizational structure as legal entities may be of particular interest for the aim of understanding barriers to integration and realization of synergies as well as flexibility with respect to changes in corporate scope.

However, these preliminary statements about the different perspectives on organizational structure are not meant to encourage researchers to keep them strictly separate. Instead, future studies can explore these perspectives' theoretical relationships, offering wonderful opportunities for new insights, as will be discussed next.

Relationships

By investigating underlying connections between the different perspectives, future research may surface important insights about organizational design that can open up entirely new research programs. An essential theoretical question involves whether there are any directional relationships between specific perspectives. For example, when does top management team structure induce or follow other changes (in divisions and legal structure)? Karim and Williams ( 2012 ) show that changes in executives’ division responsibilities helps predict subsequent reorganizations in the respective units. Another question is how the legal structure may affect the arrangement of activities over time. The greater cost of integration of legally separate entities may imply that greater autonomy is more likely to follow, which future research may want to investigate.

Moreover, it would be useful for the field of organizational design to better understand when potential structural changes in divisions and legal entities trigger in turn a reorganization of leadership responsibilities. The legal structure may change much more slowly than the other two types, because of regulatory and other legal reasons. Nevertheless, the legal structure can play an essential role in how the organization lays out its strategic priorities, is internally managed, and evaluates its performance. At least, these appear to be the main reasons of notable reorganization that lead to an overhaul in legal structure. Recent examples include the already mentioned case of Google’s legal reorganization into contained group subsidiaries under the Alphabet umbrella, Facebook’s legal reorganization into the corporation Meta (Zuckerberg 2021 ), and Lego’s reorganization into the Lego Brand Group (LEGO Group 2016 ). The question remains whether the legal reorganization is a means to enable better top management and divisional structures or whether the top management structure, for example, motivated such legal changes for better alignment.

Finally, a completely novel question that acknowledges the multifaceted perspectives of organizational structure emerges. What are the performance, innovation, and strategic change consequences for organizations when these different perspectives are aligned or misaligned? Are there specific “archetypes” organizational structures along these dimensions?

Implications

It is important to stress that in some cases it may be necessary to draw upon two or all three to gain a more holistic picture of organizational structure and important nuances that may be highly specific to a particular organization. Whereas the arrangement of activities provides an overview of distinct operating units, such as divisions and subunits, this perspective alone does not capture complex interrelationships with respect to who reports to whom. This becomes most critical in cases of a matrix organization, where, for example, a segment is guided by a product goal as well as some geographical goals.

Moreover, a comparison of some of the organizational structure characteristics between Citigroup and Ford demonstrates how important, potentially strategy-influencing differences exist when consulting all three perspectives. For example, the fact that Ford’s executive team is in part made up of executives who represent a specific legal entity, which is its own reporting segment, suggests that legal structure, decision-making and value creation for certain parts of the organization go hand in hand. In contrast, Citigroup’s legal structure bears little to no resemblance to its operational structure. This may suggest that in Citigroup’s case legal entities play a very different role for organizational design purposes, such as containing legal regulatory requirements and legal containment of liability, whereas its management of value creating activities and decision-making responsibilities is guided across these legal boundaries. Concluding that the legal structure is a reflection of operational and strategic design may be somewhat misdirected with respect to product-market operations but more reflective of risk and geographical profiles in Citigroup’s case. Future research is encouraged to explore such differences in more detail.

Limitations

Before concluding this point of view paper, it is important to acknowledge that there are other important attributes of organizational design and structure that should be considered. For example, the leadership perspective of structure may be extended or complemented by considering the structure of corporate governance and its effects on organizational changes (Castañer and Kavadis 2013 ; Goranova et al. 2007 ). Moreover, the arrangement of activities into departments, units, and divisions determines the formal structure of the organization. Employees who belong to the same department (and work on the same task) often work in the same physical location and, therefore, are more likely to interact (including outside their formal task) and form (informal) networks with those close to them (Clement and Puranam 2018 ). As such, the structure of tasks can affect the emergence of networks in the organization. Organizational changes to the arrangement of activities may consequently conflict with the informal structure that has formed over time (Gulati and Puranam 2009 ). Informal networks in the organization may, therefore, constitute another “measure” of structure, but this paper takes the perspective that networks are a more likely to be a consequence of organizational structure (albeit one that may affect future structures).

Finally, organizational design can exceed a focal firm’s boundaries. Partnerships, such as alliances, joint ventures, and meta-organizations (Gulati et al. 2012 ), pose additional challenges in determining the actual structure of an organization. Future research is advised to study how different dimensions of organizational structure extend to and impact such boundary-spanning multi-organization designs.

The divergence in prior literature with respect to conceptualizing and operationalizing organizational structure reveals that this construct has more facets to it than sometimes acknowledged. Studying the alignment and divergence of these three characteristics of structure within organizations has potential to qualify and complement prior theories and generate new insights with respect to nuances of organizational design that we may have overlooked in prior work. It is important to consider that focusing only on one of these dimensions at a time for studying structure can indeed be sufficient. However, the field of organizational design may wish to be more concise in which perspective is chosen and why, when building, testing, and extending theory. Highlighting what is not measured following a particular perspective can already enrich our understanding of the role of organizational structure in novel and impactful ways.

Data availability

Data used in this manuscript are publicly accessible through regulatory filings and company Investor Relations websites.

Albert D (2018) Organizational module design and architectural inertia: evidence from structural recombination of business divisions. Organ Sci 29(5):890–911

Article Google Scholar

Argyres N (1996) Capabilities, technological diversification and divisionalization. Strateg Manag J 17(5):395–410

Arora A, Belenzon S, Rios LA (2014) Make, buy, organize: the interplay between research, external knowledge, and firm structure. Strateg Manag J 35(3):317–337

Bethel JE, Liebeskind JP (1998) Diversification and the legal organization of the firm. Organ Sci 9(1):49–67

Bidwell MJ (2012) Politics and firm boundaries: how organizational structure, group interests, and resources affect outsourcing. Organ Sci 23(6):1622–1642

Bouquet C, Birkinshaw J (2008) Managing power in the multinational corporation: How low-power actors gain influence. J Manage 34:477–508

Burgelman RA (1983) A model of the interaction of strategic behavior, corporate context, and the concept of strategy. Acad Manage Rev 8(1):61–70

Castañer X, Kavadis N (2013) Does good governance prevent bad strategy? A study of corporate governance, financial diversification, and value creation by French corporations, 2000–2006. Strateg Manag J 34(7):863–876

Chandler AD (1962) Strategy and structure. MIT Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

Chandler AD Jr (1991) The functions of the HQ unit in the multibusiness firm. Strateg Manag J 12(S2):31–50

Citigroup Inc. Form 10-K 2022 Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Clement J, Puranam P (2018) Searching for structure: formal organization design as a guide to network evolution. Manag Sci 64(8):3879–3895

Csaszar FA (2012) Organizational structure as a determinant of performance: evidence from mutual funds. Strateg Manag J 33(6):611–632

Cyert RM, March JG (1963) A behavioral theory of the firm. Oxford: Blackwell

Eklund JC (2022) The knowledge-incentive tradeoff: understanding the relationship between research and development decentralization and innovation. Strateg Manag J 43(12):2478–2509

Ford Motor Company Exhibit 21 in Form 10-K 2022 Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Ford Motor Company Form 10-Q (Q2) Quarterly report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Foss NJ (1997) On the rationales of corporate headquarters. Ind Corp Change 6(2):313–338

Galbraith JR (1974) Organization design: an information processing view. Interfaces 4(3):28–36

Girod SJG, Whittington R (2015) Change escalation processes and complex adaptive systems: from incremental reconfigurations to discontinuous restructuring. Organ Sci 26(5):1520–1535

Goranova M, Alessandri TM, Brandes P, Dharwadkar R (2007) Managerial ownership and corporate diversification: a longitudinal view. Strateg Manag J 28(3):211–225

Guadalupe M, Li H, Wulf J (2013) Who lives in the C-Suite? Organizational structure and the division of labor in top management. Manag Sci 60(4):824–844

Gulati R, Puranam P (2009) Renewal through reorganization: the value of inconsistencies between formal and informal organization. Organ Sci 20(2):422–440

Gulati R, Puranam P, Tushman M (2012) Meta-organization design: rethinking design in interorganizational and community contexts. Strateg Manag J 33(6):571–586

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons - the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manage Rev 9(2):193–206

Hambrick DC, Humphrey SE, Gupta A (2015) Structural interdependence within top management teams: a key moderator of upper echelons predictions. Strateg Manag J 36(3):449–461

Joseph J, Gaba V (2020) Organizational structure, information processing, and decision-making: a retrospective and road map for research. Acad Manag Ann 14(1):267–302

Karim S (2006) Modularity in organizational structure: the reconfiguration of internally developed and acquired business units. Strateg Manag J 27(9):799–823

Karim S, Kaul A (2014) Structural recombination and innovation: unlocking intraorganizational knowledge synergy through structural change. Organ Sci 26(2):439–455

Karim S, Williams C (2012) Structural knowledge: how executive experience with structural composition affects intrafirm mobility and unit reconfiguration. Strateg Manag J 33(6):681–709

Keum DD (2023) Managerial political power and the reallocation of resources in the internal capital market. Strateg Manag J 44(2):369–414

Keum DD, See KE (2017) The influence of hierarchy on idea generation and selection in the innovation process. Organ Sci 28(4):653–669

Lawrence PR, Lorsch JW (1967) Organization and environment: managing differentiation and integration. Harvard University Press, Boston

Lee S (2022) The myth of the flat start-up: reconsidering the organizational structure of start-ups. Strateg Manag J 43(1):58–92

LEGO Group (2016) New structure for active family ownership of the LEGO® brand. LEGO.com . Retrieved (July 28, 2023), https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/news/2019/october/new-lego-brand-group-entity

Mintzberg H (1979) The structuring of organizations: a synthesis of research. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Monteiro LF, Arvidsson N, Birkinshaw J (2008) Knowledge flows within multinational corporations: explaining subsidiary isolation and its performance implications. Organ Sci 19(1):90–107

Pfeffer J (1981) Power in organizations. Pitman Publishing Inc., Marshfield

Pfeffer J, Salancik GR (1974) Organizational decision making as a political process - case of a university budget. Adm Sci Q 19(2):135–151

Puranam P (2018) The microstructure of organizations. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Puranam P, Vanneste B (2016) Corporate strategy: tools for analysis and decision-making. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Raveendran M (2020) Seeds of change: how current structure shapes the type and timing of reorganizations. Strateg Manag J 41(1):27–54

Reuters (2014) UBS launches share-for-share exchange for new holding company. Reuters (September 29) https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ubs-ag-holding-company-idUKKCN0HO0AH20140929

Zenger T (2015) Why Google Became Alphabet. Harvard Business Review (August 11) https://hbr.org/2015/08/why-google-became-alphabet

Zhou YM (2013) Designing for complexity: using divisions and hierarchy to manage complex tasks. Organ Sci 23:339–355

Article ADS Google Scholar

Zuckerberg M (2021) Founder’s Letter, 2021. Meta.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I appreciate the helpful comments and guidance provided by the handling editor-in-chief Marlo Raveendran and two anonymous reviewers. I also would like to thank all three editors-in-chief for supporting the publication of this point of view manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

LeBow College of Business, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA

Daniel Albert

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Albert .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Albert, D. What do you mean by organizational structure? Acknowledging and harmonizing differences and commonalities in three prominent perspectives. J Org Design 13 , 1–11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-023-00152-y

Download citation

Received : 30 March 2023

Accepted : 12 September 2023

Published : 11 October 2023

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-023-00152-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Organizational structure

- Operationalization

- Decision-making

- Legal entities

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Methodology For Studying Organizational Performance

A Multistate Survey of Front-line Providers

Karen B Lasater , PhD, RN

Olga f jarrín , phd, rn, linda h aiken , phd, rn, faan, frcn, matthew d mchugh , phd, jd, mph, rn, crnp, faan, douglas m sloane , phd, herbert l smith , phd.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Reprints: Karen B. Lasater, PhD, RN, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, 418 Curie Boulevard, Room 374R, Philadelphia, PA 19104. [email protected] .

Background:

Rigorous measurement of organizational performance requires large, unbiased samples to allow inferences to the population. Studies of organizations, including hospitals, often rely on voluntary surveys subject to nonresponse bias. For example, hospital administrators with concerns about performance are more likely to opt-out of surveys about organizational quality and safety, which is problematic for generating inferences.

The objective of this study was to describe a novel approach to obtaining a representative sample of organizations using individuals nested within organizations, and demonstrate how resurveying nonrespondents can allay concerns about bias from low response rates at the individual-level.

We review and analyze common ways of surveying hospitals. We describe the approach and results of a double-sampling technique of surveying nurses as informants about hospital quality and performance. Finally, we provide recommendations for sampling and survey methods to increase response rates and evaluate whether and to what extent bias exists.

The survey of nurses yielded data on over 95% of hospitals in the sampling frame. Although the nurse response rate was 26%, comparisons of nurses’ responses in the main survey and those of resurveyed nonrespondents, which yielded nearly a 90% response rate, revealed no statistically significant differences at the nurse-level, suggesting no evidence of nonresponse bias.

Conclusions:

Surveying organizations via random sampling of front-line providers can avoid the self-selection issues caused by directly sampling organizations. Response rates are commonly misinterpreted as a measure of representativeness; however, findings from the double-sampling approach show how low response rates merely increase the potential for nonresponse bias but do not confirm it.

Keywords: survey, survey methods, response rate, nonresponse bias, representation, hospitals

Surveys of organizations and the individuals in them are a mainstay of data collection used to evaluate and inform the delivery of health care services and quality. Survey designs used to make inferences about a population call for probability samples and high response rates. However, given endemic difficulties with survey response rates in the 21st century, 1 – 3 high response rates are increasingly difficult to achieve. High response rates are primarily desirable because they reduce the threat of nonresponse bias—the risk that samples of responding organizations and the individual respondents in them are not representative of the underlying populations. For this reason, journal editors and readers are often wary of research findings derived from surveys with low response rates.

However, a survey’s response rate provides limited information about representativeness and is “at best an indirect measure of the extent of nonresponse bias”. 1 Most important is the degree to which the sample represents the population of interest. 4 , 5 In this article, we discuss the interpretation of survey response rates in the context of nonresponse bias and population representativeness. We provide an example from the sociology of complex organizations that employ front-line providers as informants about care in organizations. 6 – 8

We use a novel survey design, which constructs organizational units (in our case, hospitals) from an individual-level sample (in our case, nurses). Our primary analytic population—and thus our target for achieving representativeness—is among the population of hospitals, with interest in the function of a number of patients served. Nurses are nested within hospitals, which gives them a primary role as informants of hospitals’ organizational properties. Because we are studying how hospital-specific features of the organization of nursing affect patient care, we are simultaneously interested in achieving representativeness of the population of patients. Thus hospitals, nurses, and patients are 3 interlocking populations, where patients and nurses are nested within the higher-order population of hospitals.

We describe how we conducted a large survey of nurses to yield an unbiased, representative sample of hospitals and the patients within them. We further describe a double-sampling approach to evaluate the extent to which nonresponse bias exists at the level of data collection (ie, nurses). Our example relies on nurses as informants about hospitals, but the lessons from our model can be applied to studies of front-line workers across the spectrum of health care organizations. 7 – 9

In the sections that follow, we:

Describe conventional methods of surveying organizations and their limitations.

Introduce an established double-sampling approach and describe its advantages.

Assess organizational representativeness and the extent of nonresponse bias.

Summarize recommendations for sampling and survey methods to increase representativeness and reduce nonresponse bias.

CONVENTIONAL METHODS OF SURVEYING ORGANIZATIONS

Conventional methods of surveying organizations rely on voluntary surveys to collect data; however, nonprobabilistic voluntary survey designs introduce the problem of self-selection of organizations as organizations may choose to participate—or not—based on what the researcher is studying. A survey of organizational performance may be at risk if persons in authority within an organization perceive their organization to be a low-performer, and are therefore disinclined to have their organization shown in a bad light. Concomitant nonresponse might also occur when surveys of organizations rely on an individual key informant. Individual informants offer a singular perspective and often hold a vested interest in their organization’s performance. Even surveys founded on the responses of multiple informants within an organization can be problematic, as it is typically necessary to obtain from each organization permission from the administration to access lists of front-line workers to serve as the sampling frame at the secondary level (ie, that of front-line workers as informants). In situations of labor-management conflict, this may be difficult. 10

Conventional methods of data collection—either 1-stage samples of organizations with appeals to key informants, or 2-stage samples requiring within-organizations sampling frames and institutional permissions 8 —can work well at certain scales and in conditions where organizations have dedicated record systems, as with patient data 11 , 12 ; and/or where key organizational actors are “on board” with respect to the research enterprise. 13 However, at large organizational scale and organizational self-selection, these conventional designs may not garner unbiased data, in the sense of representativeness of organizations such as hospitals. This was a driving motivation to reimagine methods for surveying organizations, which led us to bypass sampling at the organizational (hospital) level and to access front-line providers (nurses) directly at their home addresses, as informants about the hospitals in which they were employed.

Surveying Front-line Providers to Obtain a Representative Sample of Organizations

The first sample of our double-sampling approach to evaluate hospital care quality, organizational structure, and workforce characteristics, involved a survey of registered nurses (RN4CAST-US) conducted in 2016 in California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The 4 states were chosen for their diversity of urban and rural regions and because they include roughly 25% of Medicare beneficiary hospital discharges annually. The registered nurse sample was obtained from a 30% random sample of nurses from state licensure lists. There is no particular sampling fraction that is recommended in all cases, as it will depend on several components, including the size of the sampling frame, rates of nonresponse, the number of ineligible elements, and the number of hospitals or other organizational units. In our case, a large sample of ~231,000 nurses was used. Our primary research interest is in hospital performance and only roughly one third of registered nurses provide patient care in hospitals. 14 , 15 Others have employed a similar survey approach with a smaller sampling frame, in part because of their ability to target the survey to nurses working on particular units in hospital settings. 8 Also, we anticipated a low response rate given the lengthy 12-page questionnaire and our inability to offer financial incentives to such a large sample. 15 , 16

On the basis of our experiences estimating models with nurses grouped within hospitals, 17 and other investigations of reliability of organizational-level indicators based on aggregating worker reports 7 —which suggests a minimum of 10 nurses per hospital—plus observations on the range of nurses per hospital in hospitals of differing size ( Table 1 ), we come up with the rough identity that: sample size (~230,000)≈Target number of hospitals in study area (~750)×25 (nurses per hospital, based on 10–40 per hospital)×4 (inverse of a 25% response rate)×3 (inverse of a one third eligibility rate). None of the terms on the right of this equation were known precisely a priori, but they were posited to a degree that proved quite accurate in drawing the sample. This kind of calculus can be adjusted—researchers will need to scan the current literature as it pertains to their specific research sites, interests, and constraints—but it serves as a starting point for related applications of this design.

Hospital and Patient Representation by Hospital Size

Patient representation is derived from state discharge databases in 2015. Interquartile range (IQR) includes the middle 50th percentile, ranging from the bottom 25th percentile to the top 75th percentile.

Data collection for the RN4CAST-US survey of nurses used a modified Dillman approach to obtain the main survey sample. 15 Surveys were mailed to nurses’ home addresses with prepaid return envelopes as well as an option to complete the survey online or by phone. Nurses were asked to provide the name of their primary employer, allowing responses to be aggregated within hospitals and other health care organizations (eg, skilled nursing facilities, home health care agencies). A letter was sent by first-class mail to the home address of each of the randomly selected nurses describing the purpose of the survey and estimated arrival of the survey package. Next, the full-length survey was sent in an 8 1 2 by 11 envelope with the survey logo on the outside. One week later, thank you/reminder postcards were sent. A second survey was sent to nurses who did not respond to the original mailing, followed by a second thank you/reminder postcard. Approximately 4 months after the first mailing, nurses who had not yet responded were mailed a third survey. The fourth and final mailing occurred 6 weeks later and consisted of a thank you postcard and an abbreviated version of the survey. The main survey data collection efforts concluded after 6 months, and yielded a response rate of 26% (52,510 nurses). The responses obtained during this main survey data collection are used in our program of research to describe the organizational performance and nursing resources.

The second sample of our double-sampling approach involved an intensive resurvey of nonrespondents. Responses obtained in the second samples were used exclusively for the purposes of evaluating nonresponse bias in our main survey. The resurvey of nonrespondents involved a random sample of 1400 nonrespondents surveyed in California, Florida, and Pennsylvania using more intensive methods (eg, certified mail, phone calls, and financial incentives) that were not feasible in the initial sample of 231,000 nurses. The amount of data collected from nonrespondents was significantly pared down from the main survey. We removed the majority of questions, including those requesting respondents name their employer. We retained the most critical survey items related to employment status, setting, workload, work environment, and rating of overall care quality and safety.

To help ensure the nonrespondent sample would open our next mailing, we designed a custom multi-layer wedding-style invitation that was personalized and assembled by hand. Outer envelopes were hand-addressed, stamped, and sealed. The invitation unfolded to reveal a short note explaining the significance of their selection for the survey and to watch for a US Postal Service Priority Mail envelope containing an abbreviated version of the survey and $10 bill. This was followed by a thank you/reminder postcard. For those who did not respond, a second survey was sent 4 weeks later by FedEx. After 4 more weeks, a third survey mailing was sent by UPS to nonrespondents with a $20 bill enclosed.

When the third nonrespondent survey was mailed, an in-house call center was activated (using VanillaSoft Call Center Software). 18 The call center was staffed by nursing students who were trained by the research team. Callers were matched as well as possible with nonrespondents from their home state. A minimum of 10 attempts were made to reach each nonrespondent by phone. The phone script included a brief version of the survey, similar to the postcards used in the final wave of the main survey and mailings to nonrespondents. Refusals and do not call requests were recorded and honored. The final response rate from the nonrespondent sample was 87% after accounting for people who had died or were unreachable by mail or phone.

To examine the results of our double-sampling survey approach, we considered 2 issues: (1) representativeness and (2) nonresponse bias. With respect to representativeness, we were concerned with the extent to which our main survey of nurses obtained data from a large, unbiased sample of hospitals—and by extension, the patients receiving care within those hospitals. With respect to nonresponse bias, we were concerned with the extent to which nurse respondents differed in important ways from nonrespondents.

To assess hospital representativeness, we used publicly available data on the number of hospitals in our sampling frame and then calculated the percent of hospitals for which we had at least 1, 2, 5, and 10 nurse respondents on the main survey. The average number of nurse respondents per hospital was 32. Most hospitals (96.7%) in the 4-state sampling frame were represented in the RN4CAST-US survey by at least 1 nurse respondent ( Table 1 ). Among hospitals with >250 beds, 99.7% of hospitals were represented, compared with 88.6% of hospitals with <100 beds. Among hospitals with at least 10 nurse respondents, the sample represented 72.7% of hospitals overall, and 98.3% of hospitals with >250 beds.

Because our research interest is primarily the outcomes of patients in hospitals, 19 we assessed the extent to which patients in the 4 states were represented in our sample of hospitals. Patient representation was derived using state discharge databases from 2015. Hospitals with at least 10 nurse respondents (73% of hospital sample) account for 93% of hospitalized patients in the 4 states; and if we consider hospitals with at least 5 nurse respondents, 98% of eligible hospital patients are represented ( Table 1 ).

Did this excellent representation of hospitals and patients come at a cost? Unlike Tourangeau et al, 8 we did not have a sampling frame of nurses within hospitals, and our massive-scale mail survey of nurses to generate multiple organizational measures of hospitals resulted in a modest response rate (26% of nurses), as is typical in such efforts. We thus tested whether the response rate among nurses introduced bias in our estimates of hospital quality and performance. From our double-sampling approach, we considered nurse respondents and nonrespondents as 2 distinct groups. 20 , 21 The target population means for inference about any variable of interest can be expressed as:

where Y ¯ r and Y ¯ m are the means for the respondent and non-respondent groups (the subscripts r for respondents and m for the missing), and W r and W m are the proportions of the combined sample in these 2 groups ( W r + W m =1). Because the proportion of original nonrespondents sampled and interviewed was very high (87%) but not fully 100%, our estimate of Y ¯ m could still be slightly biased, we follow Levy and Lemeshow 22 in referring to .. as a “nearly unbiased” estimator of a characteristic of nurses (or as judged by nurses) in this population.

Evaluating the effect of nonresponse bias is thus the question of whether Y ¯ r ≈ Y ¯ m , because, when they are equivalent, Y ¯ r , what we can observe via our general sampling design, is approximately equal to Y ¯ , the population mean that is our target for inference (representation). We compared responses from the main RN4CAST-US survey (first sample) in 3 states and the corresponding nonrespondent survey (second sample), to test for differences in employment status and nurse demographics, including age, sex, and education, as well as reports of hospital quality, safety, and resources. Responses are reported in aggregate ( Table 2 ), and stratified within the state ( Table 3 ). Likelihood ratio χ 2 and 1-way analysis of variance were used to test for significance.

Comparison of Nurse Responses From the Main Survey and Nonrespondent Survey

The main survey sample results reported are data from nurses in the 3 states in which the nonresponse survey was also conducted.

P values based on likelihood ratio χ 2 and 1-way analysis of variance. Nurses were included in the respondents employed in hospitals as direct care staff nurses analysis if the nurse cared for ≤ 15 patients on their last shift.

Comparison of Nurse Responses Among Those Employed in Hospitals as Direct Care Staff Nurses From the Main Survey and the Nonrespondents Survey, by State

This analysis includes nurse respondents employed in hospitals as direct care staff nurses caring for ≤ 15 patients on their last shift. The main survey sample results reported are data from nurses in the 3 states in which the nonresponse survey was also conducted.

CA indicates California; FL, Florida, PA, Pennsylvania.

Some 52,510 registered nurses responded to the main survey and 1168 responded to the nonrespondent survey ( Table 2 ). Nonrespondents were significantly more likely to be employed in health care (85.0% vs. 72.6%, P < 0.001), and less likely to be retired (6.5% vs. 17.3%, P < 0.001). Among nurses employed in health care, there were no significant differences between nonrespondents and respondents in their setting of employment. The majority of respondents employed in health care were employed in hospitals (64.5% of main survey respondents; 64.0% of nonrespondents).

Among nurses employed in hospitals, demographics differed significantly between the 2 sample groups. Non-respondents were more likely to be male, younger, nonwhite, and Hispanic, and to have fewer years of nursing experience. No significant differences were observed between the 2 groups with respect to educational attainment.

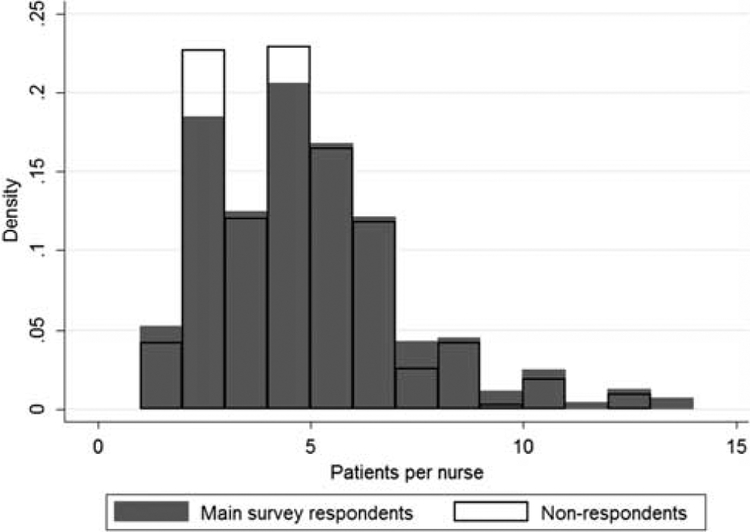

Next, we examined whether the 2 groups of nurses differed in their reports of hospital quality and performance. Respondents and nonrespondents reported provided similar ratings for the majority of hospital measures, including job satisfaction, work environment, the likelihood of recommending their hospital to family/friends, confidence in patients’ ability to manage care when discharged, confidence in management resolving problems in patient care, and overall grade on patient safety. Nonrespondents were less likely to give a favorable rating of the quality of nursing care in their hospital (80.7% vs. 85.7%, P = 0.005) and reported caring for fewer patients on their most recent shift (4.1 vs. 4.5, P = 0.008).

When we stratified the results by the state to assess the extent to which the primary variables of interest were confounded by the nurses’ geographic location of employment, we found large differences in respondents and nonrespondents across states; however, within the state the 2 samples were similar ( Table 3 ). Respondents and nonrespondents in California and Pennsylvania had similar levels of education; however, nonrespondents in Florida were significantly more likely to have a BSN degree or higher (60.6% vs. 50.4%, P = 0.018). The samples did not significantly differ within states on job satisfaction, ratings of the work environment, the likelihood of recommending their hospital to family/friends, confidence in patients’ ability to manage care when discharged, confidence in management resolving problems in patient care. Nonrespondents in California were less likely to rate the nursing care quality favorably (81.0% vs. 86.4%, P = 0.036) and those in Pennsylvania were less likely to give a good overall grade on patient safety (57.5% vs. 68.0%, P = 0.034). Unlike the aggregated data ( Table 2 ) in which nonrespondents appear to care for fewer patients per shift, within-state staffing means reveal no significant differences between the nonrespondent and main survey samples. In fact, even when the measure of patient per nurse staffing is aggregated across the 3 states, the variation in respondent and nonrespondent reports is modest ( Fig. 1 ).

Distribution of a number of patients per nurse among main survey respondents and nonrespondents. This figure includes nurse respondents employed in hospitals as direct care staff nurses caring for ≤ 15 patients on their last shift.

Using a novel method of surveying organizations—by directly sampling front-line providers nested within organizations—we demonstrate how organizational representativeness and minimal nonresponse bias can be achieved and evaluated. Our survey approach avoided self-selection of organizations by surveying front-line workers (in our case, nurses within hospitals) and accessing them outside of their place of employment (in our case, sending surveys to their home address). We obtained data on quality and safety from 96.7% of hospitals in our sampling frame, giving us confidence in the representativeness of our sample. Greater representativeness was achieved among larger hospitals (99.7% representation among hospitals with > 250 beds). Our approach disadvantaged smaller hospitals, which employed fewer nurses. Among the smallest hospitals, those with ≤ 100 beds, 88.6% had at least 1 nurse respondent, 57.7% had ≤ 5 respondents, and 26.3% had ≤ 10 respondents.

Our use of multiple informants enhanced the reliability of our estimates, an improvement from more conventional approaches, which typically rely on a single key informant. The main survey yielded an average of 32 nurse responses per hospital, sufficient to produce reliable estimates of quality and safety measures.

Survey data were collected at the nurse-level, allowing us to calculate a nurse response rate, which, in the main survey, was 26%. However, because our research interests are principally in studying hospitals, and the patients receiving care within those hospitals, the nurse response rate holds little weight in determining the sample’s representativeness of our populations of interest. In summary, response rates should not be interpreted as a summary measure of a survey’s representativeness. 2 , 23

However, response rates are not entirely meaningless. They provide insight into the potential for survey response bias—and in particular, nonresponse bias. In the case of our nurse survey, we wondered whether the respondents differed from the nonrespondents in their reports of hospital quality and performance. Our double-sampling approach, which included an intensive resurvey of nurses and yielded close to a 90% response rate, revealed no statistically significant differences on the majority of measures, suggesting no evidence of nonresponse bias at the nurse-level.

Double-sampling is considered the “gold standard” for evaluating the impact of nonresponse 12 , 24 – 26 ; however, in some cases, a double-sampling approach is not possible due to time and resource constraints. In these situations, researchers can employ alternatives. For example, differences in patterns of responses from the early, mid, and late respondents can be analyzed. No differences between the “waves” of respondents indicate a low likelihood of non-response bias, assuming that late respondents share characteristics/attitudes with nonrespondents. If differences between “waves” are observed, responses in the last wave can be used in the formula for the weighted mean to estimate the nonrespondent group.

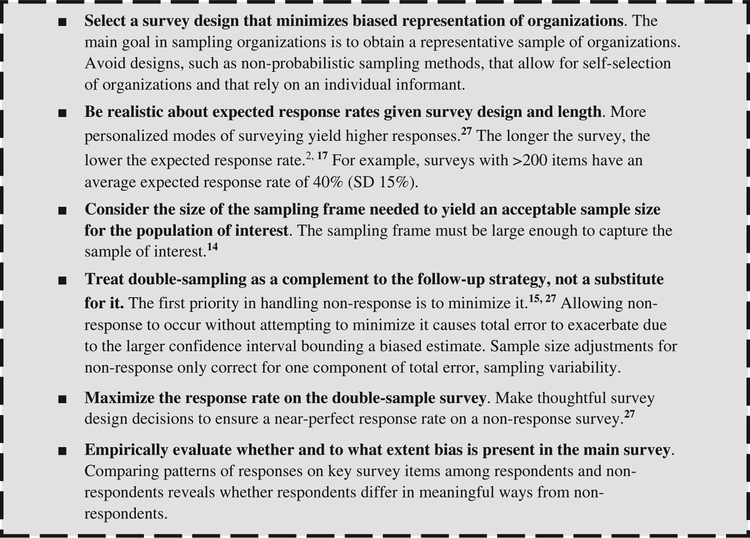

Finally, double-sampling should be used as a complementary strategy for dealing with nonresponse. The first priority in handling nonresponse is to minimize it through thoughtful sampling design decisions. 15 , 27 Reducing non-response depends on the target population, the data collection method, and the funding that can be dedicated to data collection efforts. As is the case for most aspects of sampling design, strategies to minimize nonresponse should be developed before finalizing the design. It may be worthwhile to favor a smaller sample with minimal nonresponse, over a larger sample with substantial nonresponse. In our case, we chose a 30% random sample of nurses to conserve funds for multiple waves of follow-up and intensive outreach to a subsequent random sample of nonrespondents. To summarize sampling and survey method strategies to increase representativeness and reduce nonresponse in surveys of organizations, we provide several practical recommendations ( Fig. 2 ).

Recommendations for sampling and survey methods to increase representativeness and reduce nonresponse bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Our primary goal in surveying nurses was to obtain detailed information not available from other sources in a large, representative sample of hospitals. We conclude that it is feasible to use organization members as informants through direct surveys rather than asking permission from large numbers of organizations, which can be labor intensive and time-consuming, and inevitably results in a nonrepresentative sample. A double-sampling approach that includes non-respondents is a feasible strategy to confirm the absence of nonresponse bias at the survey respondent level. Our novel approach to surveying organizations yielded a high degree of representativeness in a large population of hospitals compared with traditional methods of sampling organizations directly.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study came from the National Institutes of Health (R01NR014855, L.H.A.; P2CHD044964, H.L.S.; R00-HS022406, O.F.J.) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (71654, L.H.A.). The funding organizations did not participate in the research. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors.

These data were presented on October 26, 2018 in Lyon, France at the 10thFrench-speaking Colloquium on polls.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- 1. Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. National Research Council (NRC). Tourangeau R, Plewes TJ, eds. Nonresponse in social science surveys: a research agenda. Panel on a Research Agenda for the Future of Social Science Data Collection, Committee on National Statistics Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013:1–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Spetz J, Cimiotti JP, Brunell ML. Improving collection and use of interprofessional health workforce data: Progress and peril. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64:377–384. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Nathan G, Holt D. The effect of survey design on regression analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1980;42:377–386. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Holbrook A, Krosnick J, Pfent A, eds. The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys by the news media and government contractor survey research firms In: Lepkowski J, Tucker C, Brinck JM, De Leeuw E, Japec L, Lavrakas P, Link M, Sangster R, eds. Advances in Telephone Survey Methodology. New York, NY: Wiley; 2008:499–678. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Aiken M, Hage J. Organizational interdependence and intro-organizational structure. Am Sociol Rev. 1968;6:912–930. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Marsden PV, Landon BE, Wilson IB, et al. The reliability of survey assessments of characteristics of medical clinics. Health Serv Res. 2005; 41:265–283. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Tourangeau AE, Doran DM, McGillis Hall LM, et al. Impact of hospital nursing care on 30-day mortality for acute medical patients. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:32–44. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Cleary PD, Gross CP, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Multilevel interventions: study design and analysis issues. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012; 44:49–55. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Coffman JM, Seago JA, Spetz J. Minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in acute care hospitals in California. Health Aff. 2002;21:53–64. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Meterko M, Mohr DC, Young GJ. Teamwork culture and patient satisfaction in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42:492–498. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Young GJ, Meterko M, Desai KR. Patient satisfaction with hospital care: effects of demographic and institutional characteristics. Med Care. 2000;38:325–334. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Aiken LH, Sermeus M, Van den Heede K, et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: Cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ. 2012;344:e1717. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Dutka S, Frankel LR. Measuring response error. J Advertising Res. 1997;37:33–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Yu J, Cooper H. A quantitative review of research design effects on response rates to questionnaires. J Mark Res. 1983;20:36–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Sloane DM, Smith HL, McHugh MD, et al. Effect of changes in hospital nursing resources on improvements in patient safety and quality of care. Med Care. 2018;56:1001–1008. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR). Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys, 8th edition; 2015. Available at: www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/AAPOR_Standard-Definitions2015_8theditionwithchanges_April2015_logo.pdf . Accessed July 16, 2016.

- 19. Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, et al. The effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Med Care. 2011;49:1047–1053. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Kalton G Introduction to Survey Sampling. New York, NY: Sage; 1983. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Smith HL. A Double Sample to Minimize Bias due to Non-response in a Mail Survey. Philadelphia, PA: Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Levy P, Lemeshow S. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Peytchev A Consequences of survey nonresponse. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2013;645:88–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Hansen M, Hurwitz W. The problem of non-response in sample surveys. J Am Stat Assoc. 1946;41:517–529. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Elliott MR, Little RJ, Lewitzky S. Subsampling callbacks to improve survey efficiency. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:730–738. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Valliant R, Dever JA, Kreuter F. Practical Tools for Designing and Weighting Survey Samples. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Henry GT. Practical Sampling, Vol 21 New York, NY: Sage; 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (681.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Organizational structure is a method of organizing and dividing organizational activities, coordinating the activities of work factors and controlling the member's actions in order to work for ...

Organization structure definition Minterzberg (1972): Organizational structure is the framework of the relations on jobs, systems, operating process, people and groups making efforts to achieve the goals. ... techniques and process to turn the inputs to outputs. Woodward Research: He mostly focused on production technology and the companies ...

This note introduces basic principles of organizational design and the advantages of several common organizational structures. The principles of design are fit, differentiation, integration ...

The paper discusses how organizational structure can be conceptualized and operationalized as an arrangement of activities, a representation of decision-making, and a composition of legal entities. It also explores the implications and future research opportunities of integrating and comparing these perspectives in organizational design studies.

outset. An organization is a collection of people working together to achieve a common purpose. Organizational structure is the arrangement of people and tasks to accomplish organizational goals. Organizational design is the process of creating a structure that best fits a purpose, strategy, and environment. Because

Research on organizational structure, information processing, and decision-making has spanned over seven decades. The areas of the organization theory, ... Both authors contributed equally to this paper. 1Corresponding author. 2 We recognize that there are many definitions of organi-zational structure. Each of these definitions emphasizes

The Research Paper begins by identifying the essential elements of an organizational structure and suggesting a useful taxonomy of the various units that are typically found within the ...

New research on organizational structure from Harvard Business School faculty on issues including organizing to spark creativity, effectiveness of various organizational hierarchies, and how IT shapes top-down and bottom-up decision making. ... This paper explores organizational complexity by proposing a two-dimensional framework to help us ...

THE EFFECTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE ON EMPLOYEE TRUST AND JOB SATISFACTION by Kelli J. Dammen A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the ... writing of my research paper. To my friends and classmates for your support, help and fun times we had. To my parents, Cindy and Lee Dammen—thank you for your constant questions ...

A previous meta-analysis of dimensional structure research published during the latter half of the 20th century revealed significant intercorrelation among structural dimensions inspired by Max Weber's bureaucratic ideal type, providing support for continued research on dimensional structures and for the bureaucratic structural model that served as its theoretical foundation.