After The Bomb

Survivors of the Atomic Blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki share their stories

Photographs by HARUKA SAKAGUCHI | Introduction By LILY ROTHMAN

When the nuclear age began, there was no mistaking it. The decision by the United States to drop the world’s first atomic weapons on two Japanese cities—Hiroshima first, on Aug. 6, 1945, and Nagasaki three days later—was that rare historical moment that requires little hindsight to gain its significance. World War II would end, and the Cold War soon begin. New frontiers of science were opening, along with new and frightening moral questions. As TIME noted in the week following the bombings, the men aboard the Enola Gay could only summon two words: “My God!”

But, even as world leaders and ordinary citizens alike immediately began struggling to process the metaphorical aftershocks, one specific set of people had to face something else. For the survivors of those ruined cities, the coming of the bomb was a personal event before it was a global one. Amid the death and destruction, some combination of luck or destiny or smarts saved them—and therefore saved the voices that can still tell the world what it looks like when human beings find new and terrible ways to destroy one another.

Today, photographer Haruka Sakaguchi is seeking out those individuals, asking them to give a testimony about what they lived through and to write a message to future generations. As the anniversaries of the bombings approach once again, here is a selection of that work.

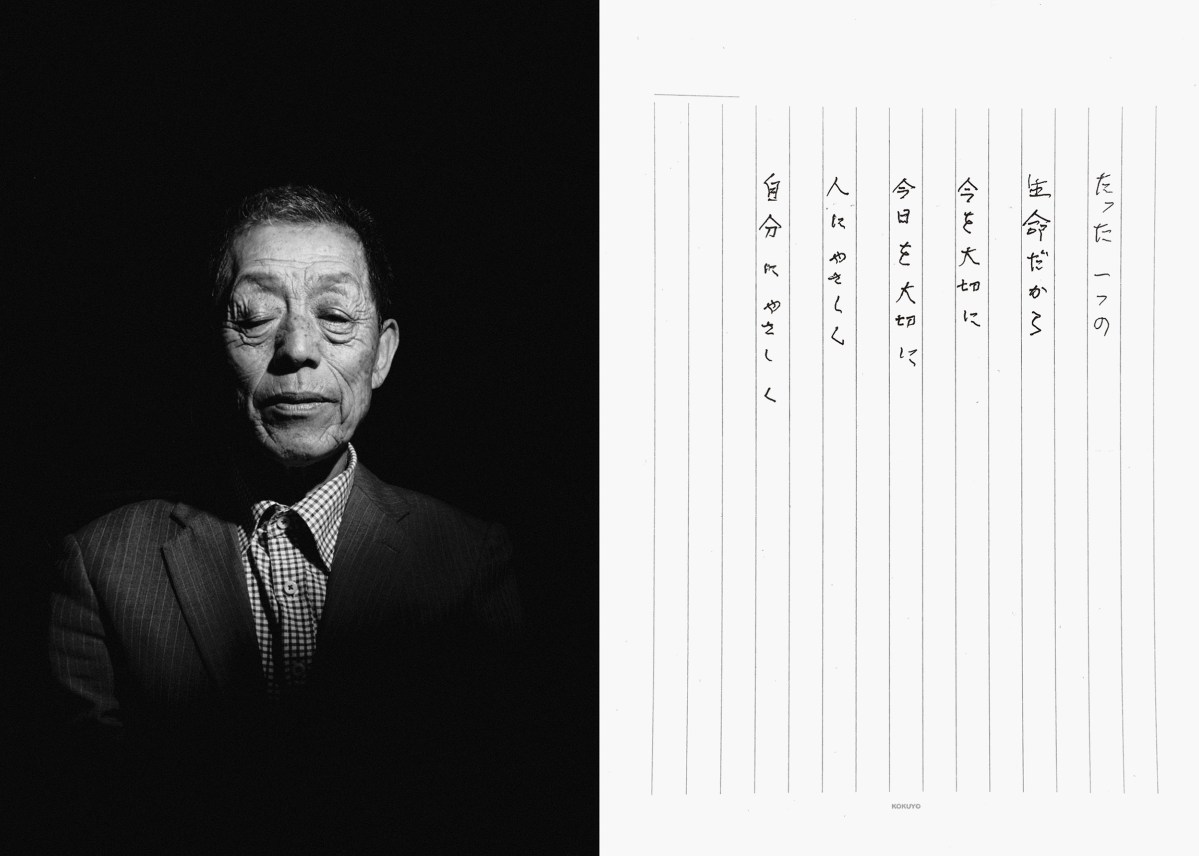

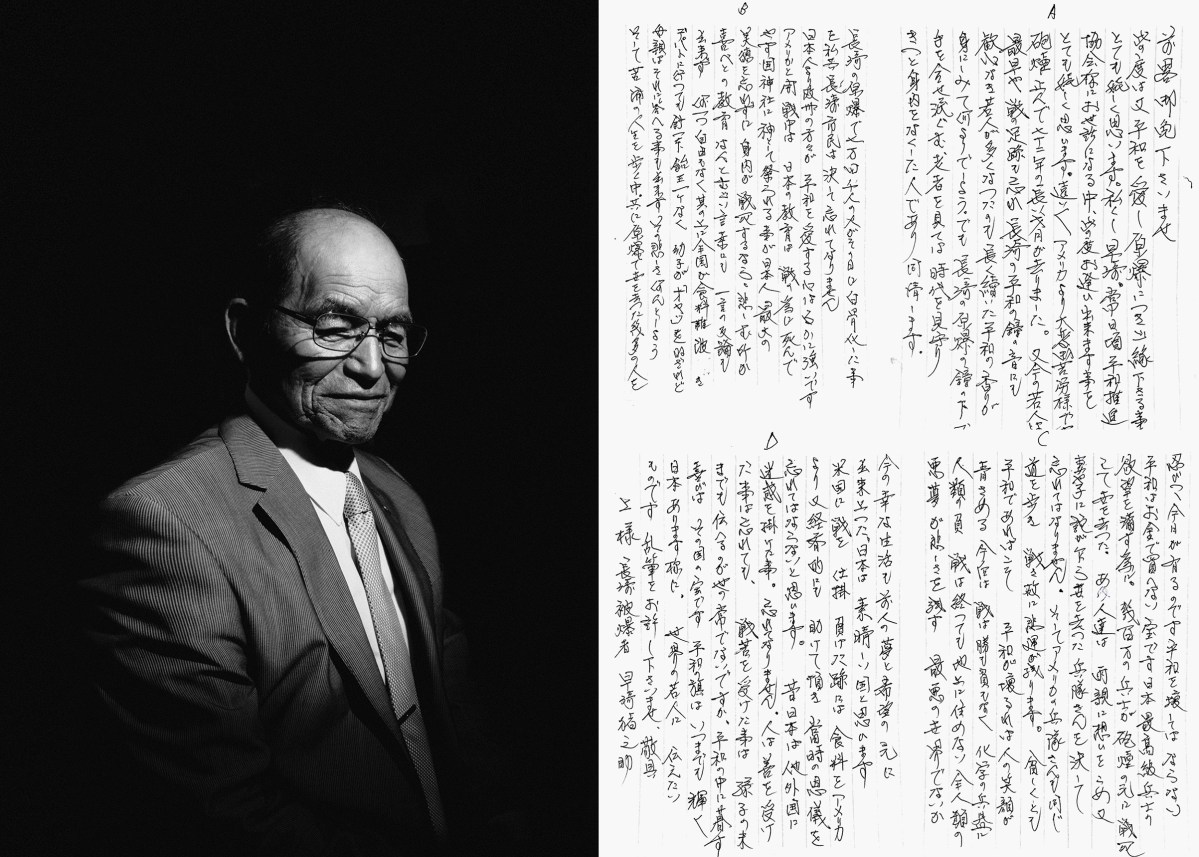

Yasujiro Tanaka age: 75 / location: nagasaki / DISTANCE from hypocenter: 3.4 km

TRANSLATION

“You are only given One life, So cherish this moment Cherish this day, Be kind to others, Be kind to yourself”

“I was three years old at the time of the bombing. I don’t remember much, but I do recall that my surroundings turned blindingly white, like a million camera flashes going off at once.

Then, pitch darkness.

I was buried alive under the house, I’ve been told. When my uncle finally found me and pulled my tiny three year old body out from under the debris, I was unconscious. My face was misshapen. He was certain that I was dead.

Thankfully, I survived. But since that day, mysterious scabs began to form all over my body. I lost hearing in my left ear, probably due to the air blast. More than a decade after the bombing, my mother began to notice glass shards growing out of her skin – debris from the day of the bombing, presumably. My younger sister suffers from chronic muscle cramps to this day, on top of kidney issues that has her on dialysis three times a week. ‘What did I do to the Americans?’ she would often say, ‘Why did they do this to me?’

I have seen a lot of pain in my long years, but truthfully, I have lived a good life. As a firsthand witness to this atrocity, my only desire is to live a full life, hopefully in a world where people are kind to each other, and to themselves.”

Sachiko Matsuo 83 / Nagasaki / 1.3 km

“Peace is our number one priority.”

“American B-29 bombers dropped leaflets all over the city, warning us that Nagasaki would ‘fall to ashes’ on August 8. The leaflets were confiscated immediately by the kenpei (Imperial Japanese Army). My father somehow got a hold of one, and believed what it said. He built us a little barrack up along the Iwayasan (a local mountain) to hide out in.

We went up there on the 7th, the 8th. The trail up to the barrack was rugged and steep. With several children and seniors in tow, it was a demanding trek. On the morning of the 9th, my mother and aunt opted for staying in the house. “Go back up to the barrack,” my father demanded. “The US is a day behind, remember?” When they opposed, he got very upset and stormed out to go to work.

We changed our minds and decided to hide out in the barrack, for one more day. That was a defining moment for us. At 11:02am that morning, the atomic bomb was dropped. Our family – those of us at the barrack, at least – survived the bomb.

We were later able to reunite with my father. However, he soon came down with diarrhea and a high fever. His hair began to fall out and dark spots formed on his skin. My father passed away – suffering greatly – on August 28.

If it weren’t for my father, we may have suffered severe burns like Aunt Otoku, or gone missing like Atsushi, or been lodged under the house and slowly burned to death. Fifty years later, I had a dream about my father for the first time since his death. He was wearing a kimono and smiling, ever so slightly. Although we did not exchange words, I knew at that moment that he was safe in heaven.”

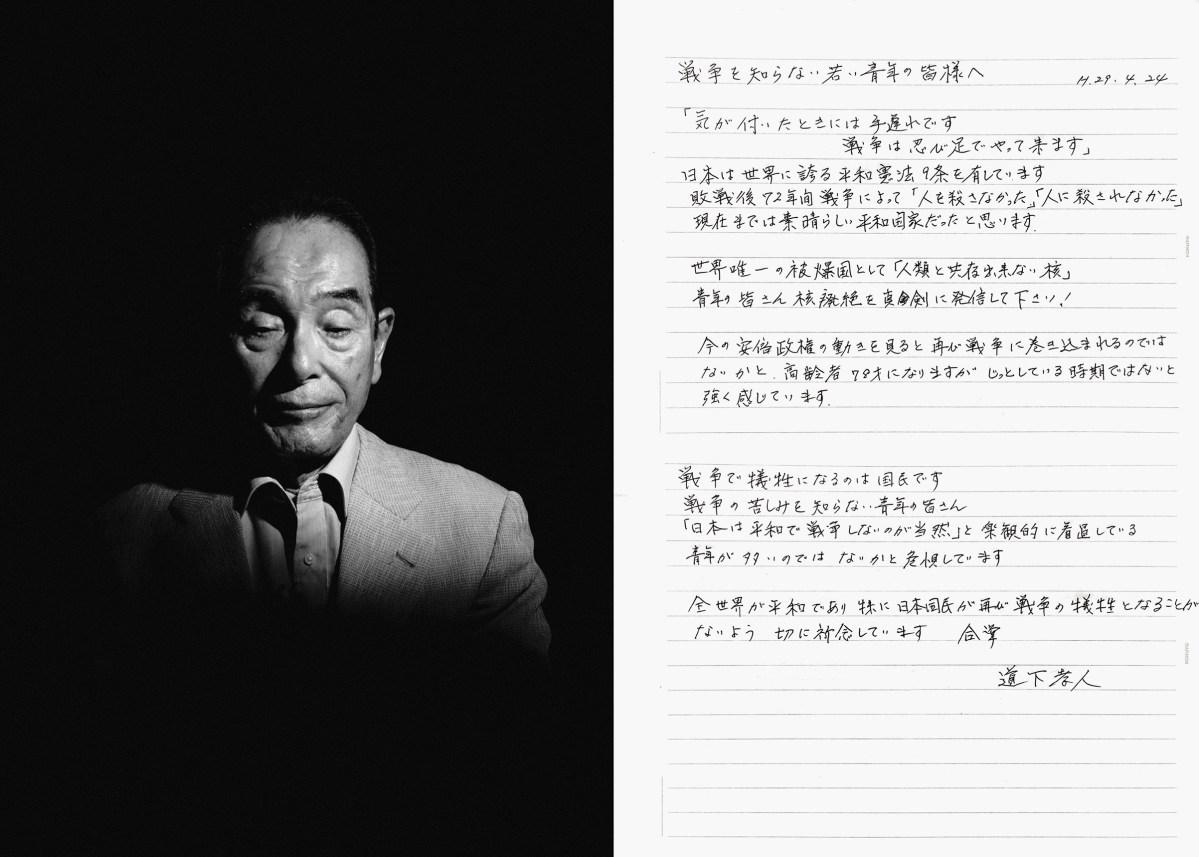

Takato Michishita 78 / Nagasaki / 4.7 km

“Dear young people who have never experienced war,

‘Wars begin covertly. If you sense it coming, it may be too late.’

Within the Japanese Constitution you will find Article 9, the international peace clause. For the past 72 years, we have not maimed or been maimed by a single human being in the context of war. We have flourished as a peaceful nation.

Japan is the only nation that has experienced a nuclear attack. We must assert, with far more urgency, that nuclear weapons cannot coexist with mankind.

The current administration is slowly leading our nation to war, I’m afraid. At the ripe age of 78, I have taken it upon myself to speak out against nuclear proliferation. Now is not the time to stand idly by.

Average citizens are the primary victims of war, always. Dear young people who have never experienced the horrors of war – I fear that some of you may be taking this hard-earned peace for granted.

I pray for world peace. Furthermore, I pray that not a single Japanese citizen falls victim to the clutches of war, ever again. I pray, with all of my heart.

“‘Don’t go to school today,’ my mother said. ‘Why?’ my sister asked.

‘Just don’t.’

Air raid alarms went off regularly back then. On August 9, however, there were no air raid alarms. It was an unusually quiet summer morning, with clear blue skies as far as the eye can see. It was on this peculiar day that my mother insisted that my older sister skip school. She said she had a ‘bad feeling.’ This had never happened before.

My sister begrudgingly stayed home, while my mother and I, aged 6, went grocery shopping. Every- one was out on their verandas, enjoying the absence of piercing warning signals. Suddenly, an old man yelled ‘Plane!’ Everyone scurried into their homemade bomb shelters. My mother and I escaped into a nearby shop. As the ground began to rumble, she quickly tore off the tatami flooring, tucked me under it and hovered over me on all fours.

Everything turned white. We were too stunned to move, for about 10 minutes. When we finally crawled out from under the tatami mat, there was glass everywhere, and tiny bits of dust and debris floating in the air. The once clear blue sky had turned into an inky shade of purple and grey. We rushed home and found my sister – she was shell-shocked, but fine.

Later, we discovered that the bomb was dropped a few meters away from my sister’s school. Every person at her school died. My mother singlehandedly saved both me and my sister that day.”

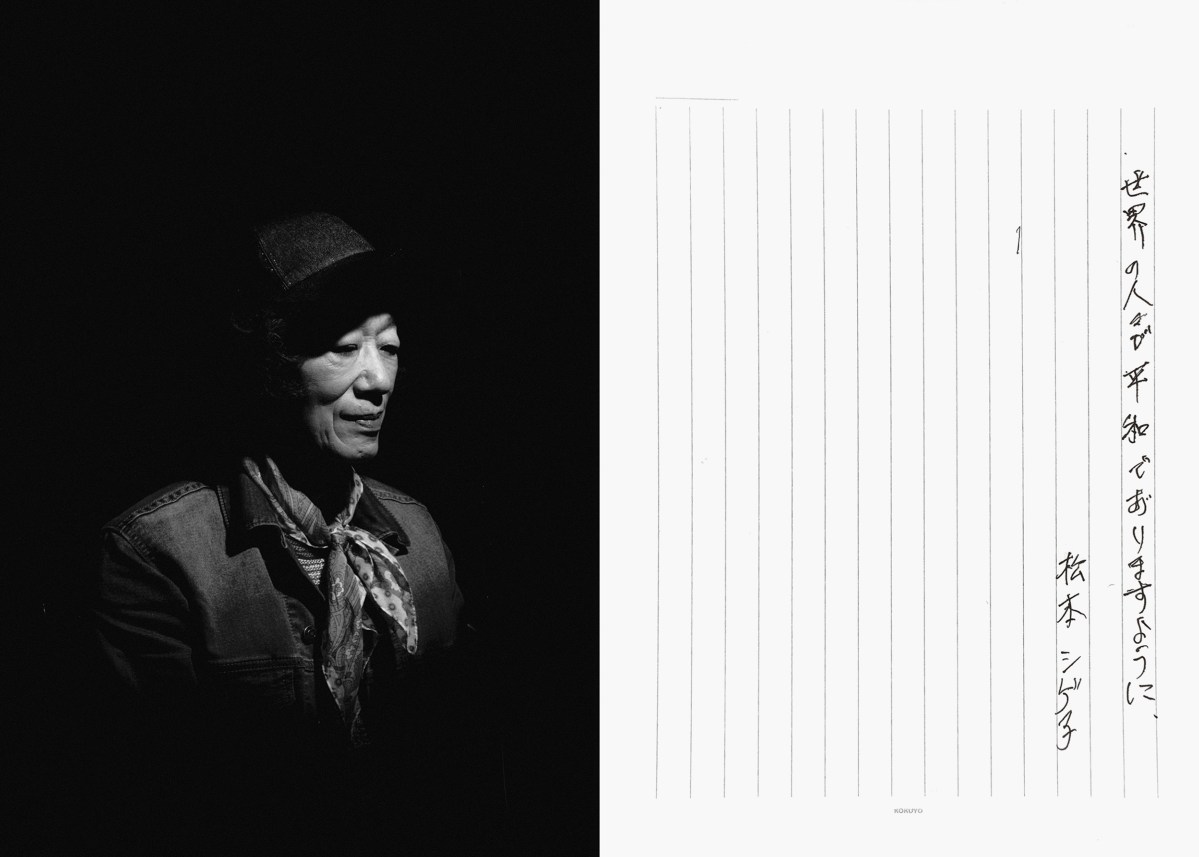

Shigeko Matsumoto 77 / Nagasaki / 800 m

“I pray that every human being finds peace. Matsumoto Shigeko”

“There were no air raid alarms on the morning of August 9, 1945. We had been hiding out in the local bomb shelter for several days, but one by one, people started to head home. My siblings and I played in front of the bomb shelter entrance, waiting to be picked up by our grandfather.

Then, at 11:02am, the sky turned bright white. My siblings and I were knocked off our feet and violently slammed back into the bomb shelter. We had no idea what had happened.

As we sat there shell-shocked and confused, heavily injured burn victims came stumbling into the bomb shelter en masse. Their skin had peeled off their bodies and faces and hung limply down on the ground, in ribbons. Their hair was burnt down to a few measly centimeters from the scalp. Many of the victims collapsed as soon as they reached the bomb shelter entrance, forming a massive pile of contorted bodies. The stench and heat were unbearable.

My siblings and I were trapped in there for three days.

Finally, my grandfather found us and we made our way back to our home. I will never forget the hellscape that awaited us. Half burnt bodies lay stiff on the ground, eye balls gleaming from their sockets. Cattle lay dead along the side of the road, their abdomens grotesquely large and swollen. Thousands of bodies bopped up and down the river, bloated and purplish from soak- ing up the water. ‘Wait! Wait!’ I pleaded, as my grandfather treaded a couple paces ahead of me. I was terrified of being left behind.”

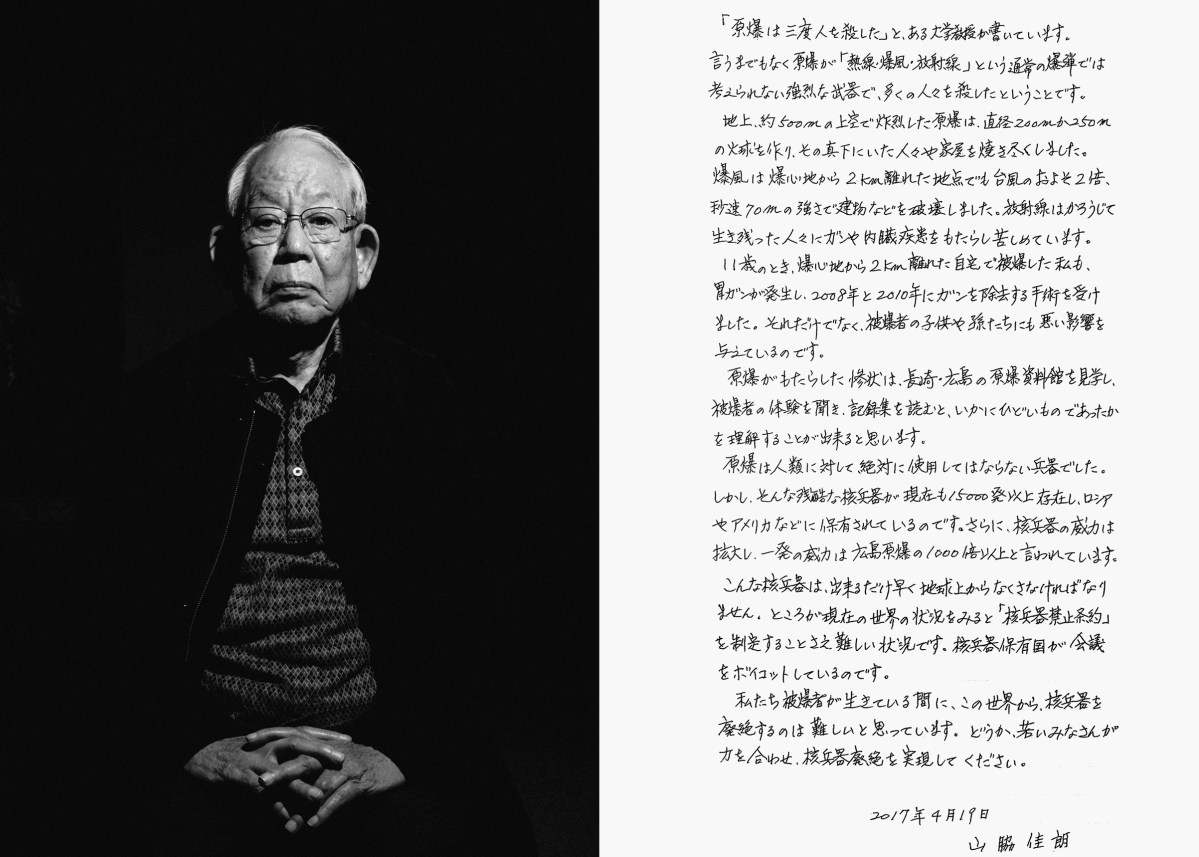

Yoshiro Yamawaki 83 / Nagasaki / 2.2 km

“‘The atom bomb killed victims three times,’ a college professor once said. Indeed, the nuclear blast has three components – heat, pressure wave, and radiation – and was unprecedented in its ability to kill en masse.

The bomb, which detonated 500m above ground level, created a bolide 200-250m in diameter and implicated tens of thousands of homes and families underneath. The pressure wave created a draft up to 70m/sec – twice that of a typhoon – which instantly destroyed homes 2km in radius from the hypo- center. The radiation continues to affect survivors to this day, who struggle with cancer and other debilitating diseases.

I was 11 years old when the bomb was dropped, 2km from where I lived. In recent years, I have been diagnosed with stomach cancer, and have undergone surgery in 2008 and 2010. The atomic bomb has also implicated our children and grandchildren.

One can understand the horrors of nuclear warfare by visiting the atomic bomb museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, listening to first-hand accounts of hi- bakusha survivors, and reading archival documents from that period.

Nuclear weapons should, under no circumstances, be used against humans. However, nuclear powers such as the US and Russia own stockpiles of well over 15,000 nuclear weapons. Not only that, technological advances have given way to a new kind of bomb that can deliver a blast over 1,000 times that of the Hiroshima bombing.

Weapons of this capacity must be abolished from the earth. However, in our current political climate we struggle to come to a consensus, and have yet to implement a ban on nuclear weapons. This is largely because nuclear powers are boycotting the agreement.

I have resigned to the fact that nuclear weapons will not be abolished during the lifetime of us first generation hibakusha survivors. I pray that younger generations will come together to work toward a world free of nuclear weapons.

“One incident I will never forget is cremating my father. My brothers and I gently laid his blackened, swollen body atop a burnt beam in front of the factory where we found him dead and set him alight. His ankles jutted out awkwardly as the rest of his body was engulfed in flames.

When we returned the next morning to collect his ashes, we discovered that his body had been partially cremated. Only his wrists, ankles, and part of his gut were burnt properly. The rest of his body lay raw and decomposed. I could not bear to see my father like this. ‘We have to leave him here,’ I urged my brothers. Finally, my oldest brother gave in, suggesting that we take a piece of his skull – based on a common practice in Japanese funerals in which family members pass around a tiny piece of the skull with chopsticks after cremation – and leave him be.

As soon as our chopsticks touched the surface, however, the skull cracked open like plaster and his half cremated brain spilled out. My brothers and I screamed and ran away, leaving our father behind. We abandoned him, in the worst state possible.”

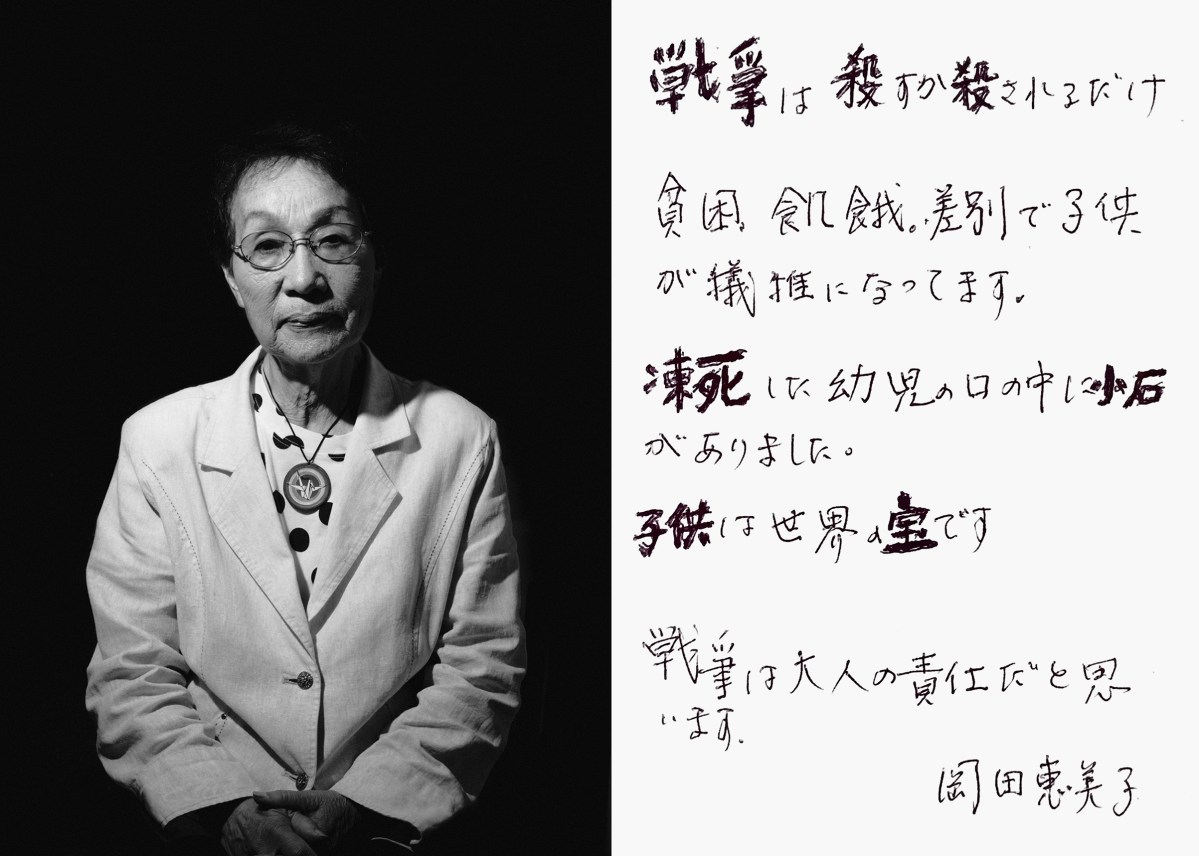

Emiko Okada 80 / hiroshima / 2.8 km

“War is one of two things: either you kill, or get killed.

Many children are victimized by poverty, malnutrition, and discrimination to this day.

I once encountered an infant who died of hypothermia. In its mouth was a small pebble.

Children are our greatest blessing.

I believe that grownups are responsible for war. Emiko Okada”

“Hiroshima is known as a ‘city of yakuza.’ Why do you think that is? Thousands of children were orphaned on August 6, 1945. Without parents, these young children had to fend for themselves. They stole to get by. They were taken in by the wrong adults. They were later bought and sold by said adults. Orphans who grew up in Hiroshima harbor a special hatred for grownups.

I was eight when the bomb dropped. My older sister was 12. She left early that morning to work on a tatemono sokai (building demolition) site and never came home. My parents searched for her for months and months. They never found her remains. My parents refused to send an obituary notice until the day that they died, in hopes that she was healthy and alive somewhere, somehow.

I too was affected by the radiation and vomited profusely after the bomb attack. My hair fell out, my gums bled, and I was too ill to attend school. My grandmother lamented the suffering of her children and grandchildren and prayed. “How cruel, how so very cruel, if only it weren’t for the pika-don (phonetic name for the atomic bomb)…” This was a stock phrase of hers until the day that she died.

The war was caused by the selfish misdeeds of adults. Many children fell victim because of it. Alas, this is still the case today. Us adults must do everything we can to protect the lives and dignity of our children. Children are our greatest blessing.”

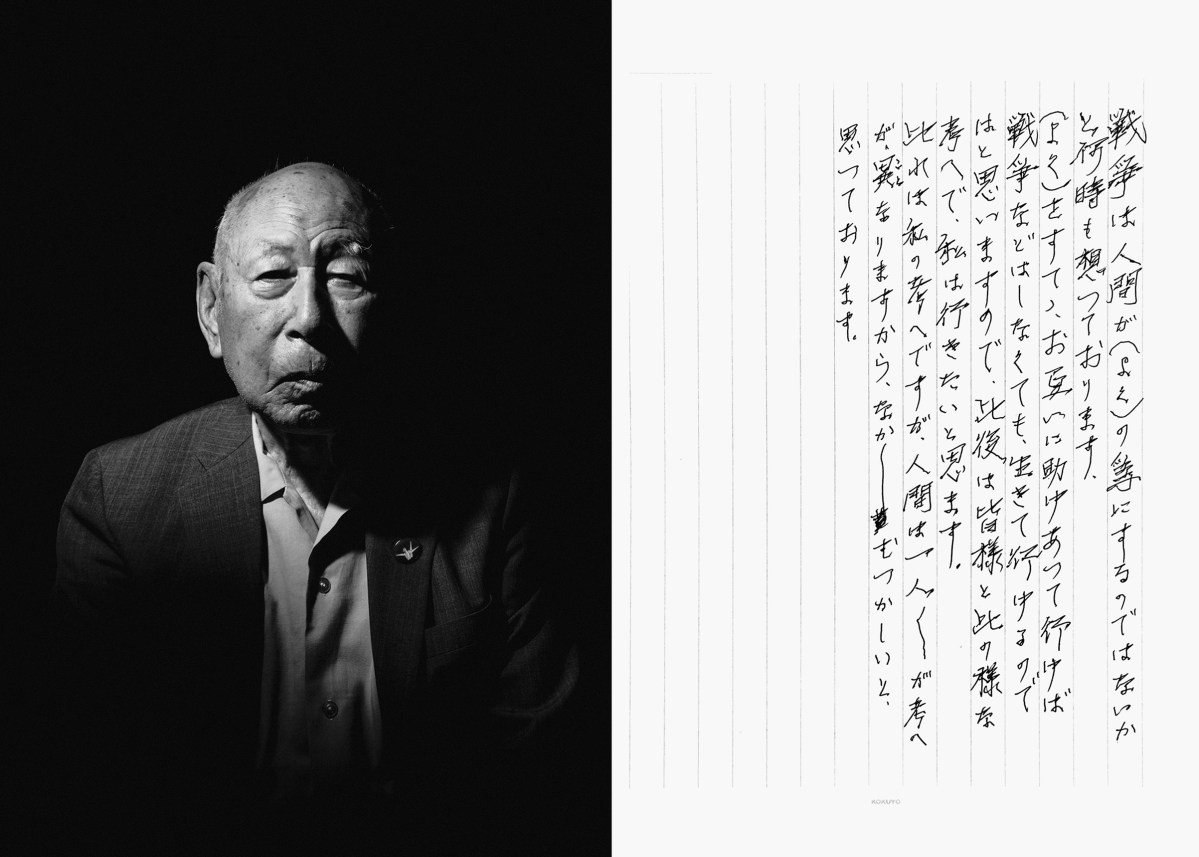

Masakatsu Obata 99 / nagasaki / 1.5 km

“I often think that humans go into war to satisfy their greed. If we rid ourselves of greed and help each other instead, I believe that we will be able to coexist without war. I hope to live on with everyone else, informed by this logic.

This is just a thought of mine – each person has differing thoughts and ideologies, which is what makes things challenging.”

“I was working at the Mitsubishi factory on the morning of August 9. An alert warning went off. ‘I wonder if there will be another air raid today,’ a coworker pondered. Just then, the alert warning turned into an air raid warning.

I decided to stay inside the factory. The air raid warning eventually subsided. It must have been around 11. I started to look forward to the baked potato that I had brought for lunch that day, when suddenly, I was surrounded by a blinding light. I immediately dropped on my stomach. The slated roof and walls of the factory crumbled and fell on top of my bare back. ‘I’m going to die,’ I thought. I longed for my wife and daughter, who was only several months old.

I rose to my feet some moments later. The roof had been completely blown off our building. I peered up at the sky. The walls were also destroyed – as were the houses that surrounded the factory – revealing a dead open space. The factory motor had stopped running. It was eerily quiet. I immediately headed to a nearby air raid shelter.

There, I encountered a coworker who had been exposed to the bomb outside of the factory. His face and body were swollen, about one and a half times the size. His skin was melted off, exposing his raw flesh. He was helping out a group of young students at the air raid shelter.

‘Do I look alright?’ he asked me. I didn’t have the heart to answer. ‘You look quite swollen,’ were the only words I could muster. The coworker died three days later, or so I’ve heard.”

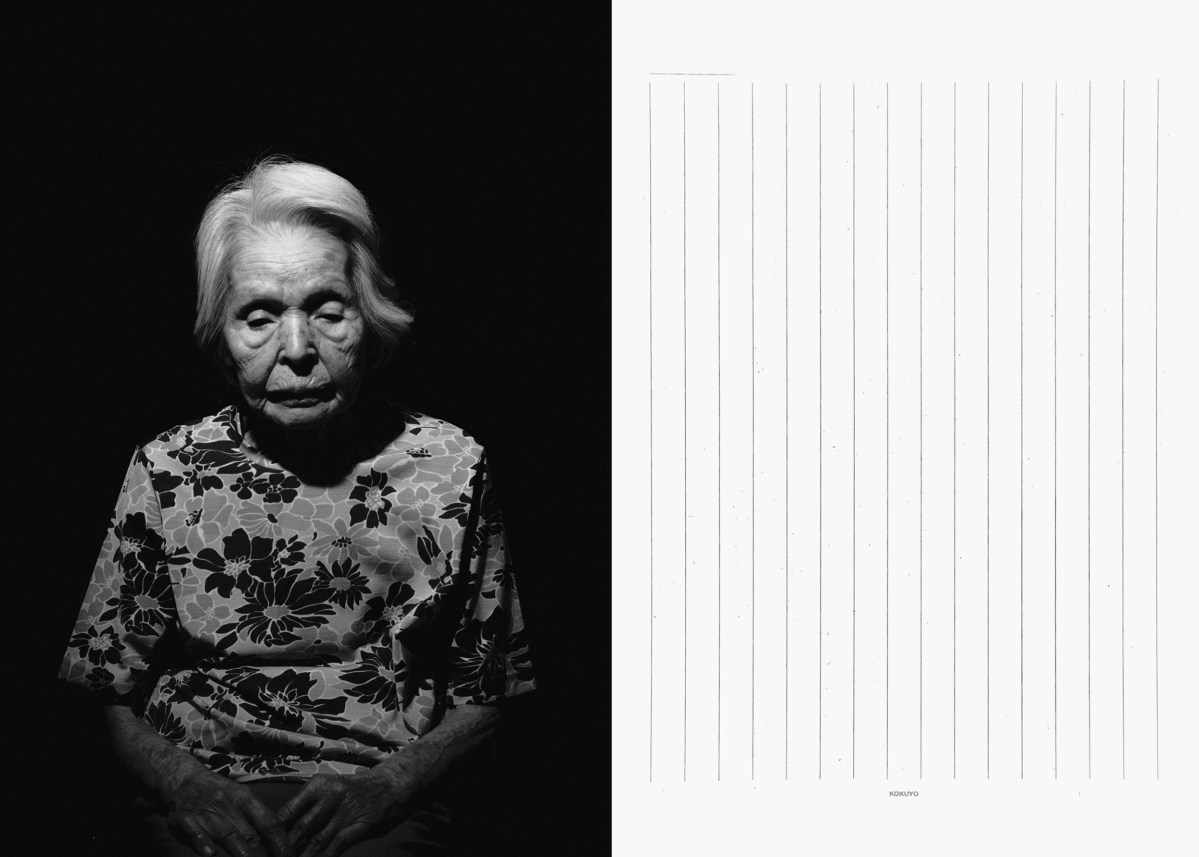

Kumiko Arakawa 92 / nagasaki / 2.9 km

Ms. Arakawa has very little recollection of how she survived the bombing after August 9, having lost both of her parents and four siblings to the atomic bomb attack. When asked to write a message for future generations, she replied, “Nani mo omoitsukanai (I can’t think of anything).”

“I was 20 years old when the bomb was dropped. I lived in Sakamotomachi – 500m from the hypocenter – with my parents and eight siblings. As the war situation intensified, my three youngest sisters were sent off to the outskirts and my younger brother headed to Saga to serve in the military.

I worked at the prefectural office. As of April of 1945, our branch temporarily relocated to a local school campus 2.9km away from the hypocenter because our main office was beside a wood building (author’s note: flammable in case of an air strike). On the morning of August 9, several friends and I went up to the rooftop to look out over the city after a brief air raid. As I peered up, I saw something long and thin fall from the sky. At that moment, the sky turned bright and my friends and I ducked into a nearby stairwell.

After a while, when the commotion subsided, we headed to the park for safety. Upon hearing that Sakamotoma- chi was inaccessible due to fires, I decided to stay with a friend in Oura. As I headed back home the next day, an acquaintance informed me that my parents were at an air raid shelter nearby. I headed over and found both of them suffering severe burns. They died, two days later.

My older sister was killed by the initial blast, at home. My two younger sisters were injured heavily and died within a day of the bombing. My other sister was found dead at the foyer of our house. There are countless tombstones all over Nagasaki with a name inscription but no ikotsu (cremated bone remains). I take solace in the fact that all six members of my family have ikotsu and rest together peacefully.

At age 20, I was suddenly required to support my surviving family members. I have no recollection of how I put my younger sisters through school, who we relied on, how we survived. Some people have asked me what I saw on my way home the day after the bombing, on August 10 – ‘surely you saw many dead bodies,’ they would say – but I don’t recall seeing a single corpse. It sounds strange, I’m sure – but it is the truth.

I am now 92 years old. I pray everyday that my grandchildren and great-grandchildren spend their entire lives knowing only peace.”

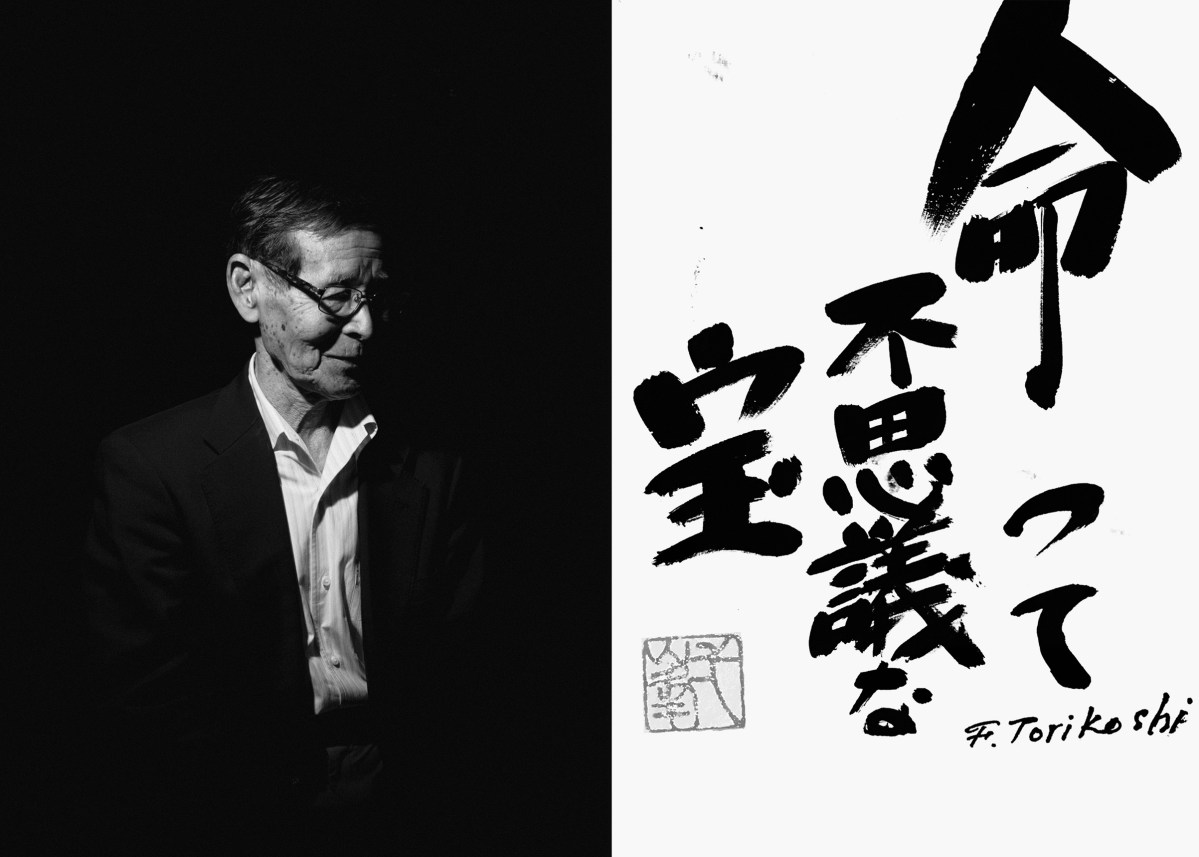

Fujio Torikoshi 86 / hiroshima / 2 KM

“Life is a curious treasure.”

“On the morning of August 6, I was preparing to go to the hospital with my mother. I had been diagnosed with kakke (vitamin deficiency) a few days earlier and had taken the day off school to get a medical exam. As my mother and I were eating breakfast, I heard the deep rumble of engines overhead. Our ears were trained back then; I knew it was a B-29 immediately. I stepped out into the field out front but saw no planes.

Bewildered, I glanced to the northeast. I saw a black dot in the sky. Suddenly, it ‘burst’ into a ball of blinding light that filled my surroundings. A gust of hot wind hit my face; I instantly closed my eyes and knelt down to the ground. As I tried to gain footing, another gust of wind lifted me up and I hit something hard. I do not remember what happened after that.

When I finally came to, I was passed out in front of a bouka suisou (stone water container used to extinguish fires back then). Suddenly, I felt an intense burning sensation on my face and arms, and tried to dunk my body into the bouka suisou. The water made it worse. I heard my mother’s voice in the distance. ‘Fujio! Fujio!’ I clung to her desperately as she scooped me up in her arms. ‘It burns, mama! It burns!’

I drifted in and out of consciousness for the next few days. My face swelled up so badly that I could not open my eyes. I was treated briefly at an air raid shelter and later at a hospital in Hatsukaichi, and was eventually brought home wrapped in bandages all over my body. I was unconscious for the next few days, fighting a high fever. I finally woke up to a stream of light filtering in through the bandages over my eyes and my mother sitting beside me, playing a lullaby on her harmonica.

I was told that I had until about age 20 to live. Yet here I am seven decades later, aged 86. All I want to do is forget, but the prominent keloid scar on my neck is a daily reminder of the atomic bomb. We cannot continue to sacrifice precious lives to warfare. All I can do is pray – earnestly, relentlessly – for world peace.”

Inosuke Hayasaki 86 / nagasaki / 1.1 km

“I am very thankful for the opportunity to meet with you and speak with you about world peace and the implications of the atom bomb.

I, Hayasaki, have been deeply indebted to the Heiwasuishinkyokai for arranging this meeting, amongst many other things. You have traveled far from the US – how long and arduous your journey must have been. Seventy two years have passed since the bombing – alas, young people of this generation have forgotten the tragedies of war and many pay no mind to the Peace Bell of Nagasaki. Perhaps this is for the better, an indication that the current generation revels in peace. Still, whenever I see people of my own generation join their hands before the Peace Bell, my thoughts go out to them.

May the citizens of Nagasaki never forget the day when 74,000 people were instantaneously turned into dust. Currently, it seems Americans have a stronger desire for peace than us Japanese. During the war, we were told that the greatest honor was to die for our country and be laid to rest at the Yasukuni Shrine.

We were told that we should not cry but rejoice when family members died in the war effort. We could not utter a single word of defiance to these cruel and merciless demands; we had no freedoms. In addition, the entire country was starving – not a single treat or needle to be seen at the department store. A young child may beg his mother for a snack but she could do nothing – can you imagine how tormenting that is to a mother?

“The injured were sprawled out over the railroad tracks, scorched and black. When I walked by, they moaned in agony. ‘Water… water…’

I heard a man in passing announce that giving water to the burn victims would kill them. I was torn. I knew that these people had hours, if not minutes, to live. These burn victims – they were no longer of this world.

‘Water… water…’

I decided to look for a water source. Luckily, I found a futon nearby engulfed in flames. I tore a piece of it off, dipped it in the rice paddy nearby, and wrang it over the burn victims’ mouths. There were about 40 of them. I went back and forth, from the rice paddy to the railroad tracks. They drank the muddy water eagerly. Among them was my dear friend Yamada. ‘Yama- da! Yamada!’ I exclaimed, giddy to see a familiar face. I placed my hand on his chest. His skin slid right off, exposing his flesh. I was mortified. ‘Water…’ he murmured. I wrang the water over his mouth. Five minutes later, he was dead.

In fact, most of the people I tended to were dead.

I cannot help but think that I killed those burn victims. What if I hadn’t given them water? Would many of them have lived? I think about this everyday.”

We would not be where we are today if it weren’t for the countless lives that

were lost due to the bombing, and the many survivors who have lived in pain and struggle since. We cannot shatter this momentum of peace – it is priceless. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers died under the insurmountable greed of the Japanese military elite class. We cannot forget those young soldiers who silently longed for their parents, yearned for their wives and children as they passed away amidst the chaos of war. American soldiers have faced similar hardships. We must cherish peace, even if it leaves us poor. The smile pales when peace is taken from us. Wars of today no longer yield winners and losers – we all become losers, as our habitats become inhabitable. We must remember that our happiness today is built upon the hopes and dreams of those that passed before us.

Japan is a phenomenal country – however, we must be cognizant of the fact that we waged war on the US, and received aid from them afterwards. We must be cognizant of the pain that we inflicted upon our neighbors during the war. Fa- vors and good deeds are often forgotten, but trauma and misdeeds are passed on from one generation to the other – such is the way the world works. The ability to live in peace is a country’s most prized commodity. I pray that Japan continues to be a shining example of peace and harmony. I pray that this message resonates with young people all over the globe. Please excuse my handwriting.

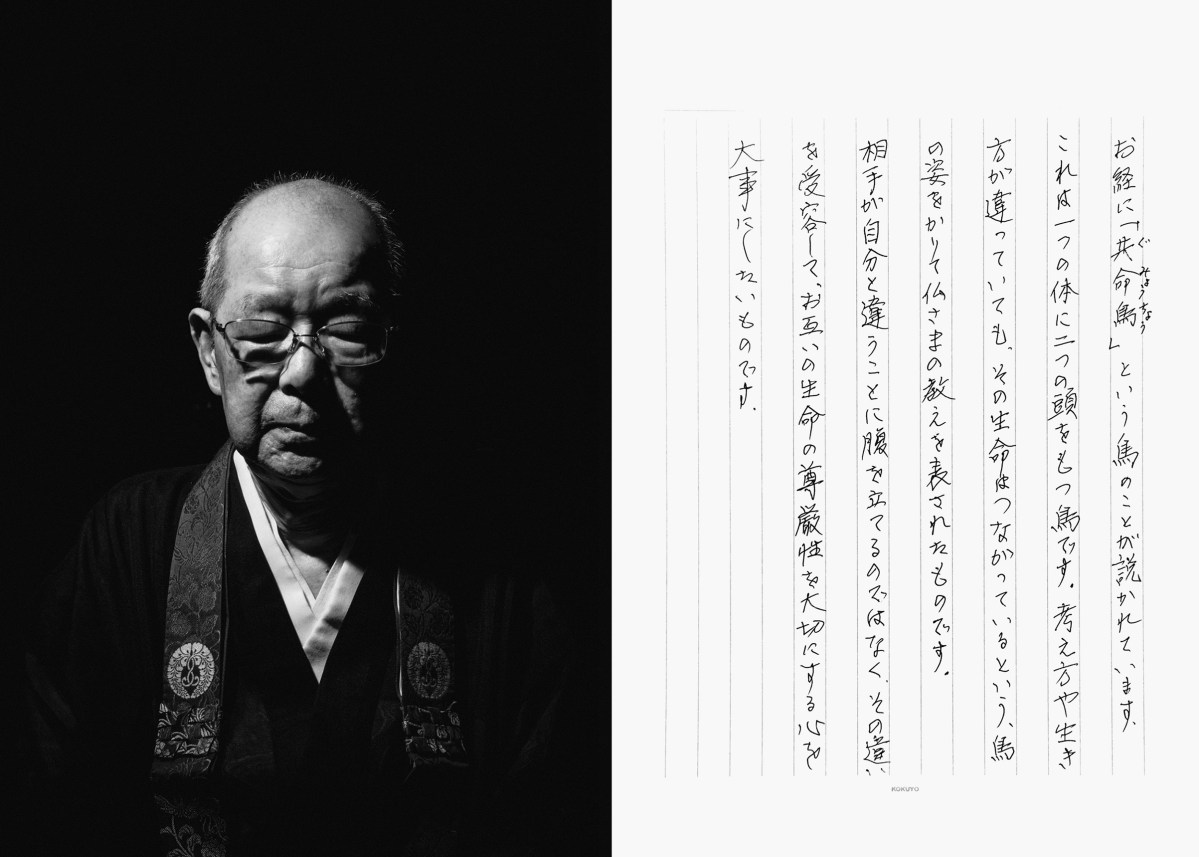

Ryouga Suwa 84 / hiroshima / entered the affected area after the bombing and was exposed to radiation

“Within the Buddhist vernacular, there is a bird called the gumyouchou. This bird has one body and two heads. Even if two entities have differing ideologies or philosophies, their lives are bound together by a single form – this is a Buddhist principle manifested in the form of a bird.

It would be ideal if we could all cultivate in us the ability to dignify each other instead of getting upset over our differences.”

“I am the 16th generation chief priest of Johoji Temple in Otemachi. The original Johoji Temple was within 500m of the hypocenter. It was instantly destroyed, along with the 1300 households that used to make up the area that is now called Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. My parents remain missing to this day and my sister Reiko was pronounced dead.

I, on the other hand, was evacuated in Miyoshi-shi, 50km away from the hypocenter. I am what you would call a genbaku-koji (atomic bomb orphan). I was 12 years old at the time. When I returned to Hiroshima on September 16 – one month and 10 days after the bomb attack – what remained of the property was a cluster of overturned tombstones from the temple cemetery. Hiroshima was a flat wasteland. I remember feeling shocked that I could make out the Setonai Islands in the distance, which used to be inhibited by buildings.

In 1951, the temple was relocated to its current address. The new Johoji was rebuilt by the hands of our supporters and thrived along with the eventual revival of Hiroshima City. We practice an anti-war and anti-nuclear weapons philosophy here and have partnered with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park every year to coordinate lectures and events and pursue hibaku building restoration projects.”

Haruka Sakaguchi is a photographer based in New york City

Paul Moakley , who edited this photo essay, is time ‘s Deputy Director of Photography

Lily Rothman is time ‘s History and Archives Editor

Your browser is out of date. Please update your browser at http://update.microsoft.com

Was the US justified in dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War?

For years debate has raged over whether the US was right to drop two atomic bombs on Japan during the final weeks of the Second World War. The first bomb, dropped on the city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, resulted in a total death toll of around 140,000. The second, which hit Nagasaki on 9 August, killed around 50,000 people. But was the US justified? We put the question to historians and two HistoryExtra readers...

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

America's use of atomic bombs to attack the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 has long remained one of the most controversial decisions of the Second World War . Here, a group of historians offer their views on whether US president Truman was right to authorise these nuclear attacks...

“Yes. Truman had little choice” – Antony Beevor

Few actions in war are morally justifiable. All a commander or political leader can hope to assess is whether a particular course of action is likely to reduce the loss of life. Faced with the Japanese refusal to surrender, President Truman had little choice.

His decision was mainly based on the estimate of half a million Allied casualties likely to be caused by invading the home islands of Japan . There was also the likely death rate from starvation for Allied PoWs and civilians as the war dragged on well into 1946.

- Read more | The Manhattan Project: your guide to the building of the first atomic bomb

What Truman did not know, and which has only been established quite recently, is that the Imperial Japanese Army could never contemplate surrender, having forced all their men to fight to the death since the start of the war. All civilians were to be mobilised and forced to fight with bamboo spears and satchel charges to act as suicide bombers against Allied tanks. Japanese documents apparently indicate their army was prepared to accept up to 28 million civilian deaths.

Antony Beevor is a bestselling military historian, specialising in the Second World War. His most recent book is Ardennes 1944: Hitler’s Last Gamble (Viking, 2015)

“No. It was immoral, and unnecessary” – Richard Overy

The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was justified at the time as being moral – in order to bring about a more rapid victory and prevent the deaths of more Americans. However, it was clearly not moral to use this weapon knowing that it would kill civilians and destroy the urban milieu. And it wasn’t necessary either.

WW2 | The Big Questions

Listen to all episodes now.

Militarily Japan was finished (as the Soviet invasion of Manchuria that August showed). Further blockade and urban destruction would have produced a surrender in August or September at the latest, without the need for the costly anticipated invasion or the atomic bomb. As for the second bomb on Nagasaki, that was just as unnecessary as the first one. It was deemed to be needed, partly because it was a different design, and the military (and many civilian scientists) were keen to see if they both worked the same way. There was, in other words, a cynical scientific imperative at work as well.

I should also add that there was a fine line between the atomic bomb and conventional bombing – indeed descriptions of Hamburg or Tokyo after conventional bombing echo the aftermath of Hiroshima. To regard Hiroshima as a moral violation is also to condemn the firebombing campaign, which was deliberately aimed at city centres and completely indiscriminate.

Of course it is easy to say that if I had been in Truman’s shoes, I would not have ordered the two bombings. But it is possible to imagine greater restraint. The British and Americans had planned in detail the gas-bombing of a list of 17 major German cities, but in the end did not carry it out because the moral case seemed to depend on Germany using gas first. Restraint was possible, and, at the very end of the war, perhaps more politically acceptable.

Richard Overy is a professor of history at the University of Exeter and editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of World War Two (OUP, 2015)

More from us

- WW2 the big questions: final stages of the conflict

- What if...The Enigma code had not been cracked by Alan Turing and Bletchley Park?

- Oppenheimer | Is Christopher Nolan perpetuating a historical myth?

- The PoWs who survived Nagasaki

- "We’ve come to think that peace is normal, but that's not the reality": Margaret MacMillan on humanity's compulsion to go to war

“Yes. It was the least bad option” – Robert James Maddox

The atomic bombs were horrible, but I agree with US secretary of war Henry L Stimson that using them was the “least abhorrent choice”. A bloody invasion and round-the-clock conventional bombing would have led to a far higher death toll and so the atomic weapons actually saved thousands of American and millions of Japanese lives. The bombs were the best means to bring about unconditional surrender, which is what the US leaders wanted. Only this would enable the Allies to occupy Japan and root out the institutions that led to war in the first place.

- Timeline | The countdown to the bombing of Hiroshima

The experience with Germany after the First World War had persuaded them that a mere armistice would constitute a betrayal of future generations if an even larger war occurred 20 years down the line. It is true that the radiation effects of the atomic bomb provided a grisly dividend, which the US leaders did not anticipate. However, even if they had known, I don’t think it would have changed their decision.

Robert James Maddox is author of Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism (University of Missouri Press, 2007)

Video: Could the Nazis have built the first atomic bomb?

“no. japan would have surrendered anyway” – martin j sherwin.

I believe that it was a mistake and a tragedy that the atomic bombs were used. Those bombings had little to do with the Japanese decision to surrender. The evidence has become overwhelming that it was the entry of the Soviet Union on 8 August into the war against Japan that forced surrender but, understandably, this view is very difficult for Americans to accept.

Of the Japanese leaders, it was the military ones who held out against the civilian leaders who were closest to the emperor, and who wanted to surrender provided the emperor’s safety would be guaranteed. The military’s argument was that Japan could convince the Soviet Union to mediate on its behalf for better surrender terms than unconditional surrender and therefore should continue the war until that was achieved.

- Read more | How and when did the Second World War end?

Once the USSR entered the war, the Japanese military not only had no arguments for continuation left, but it also feared the Soviet Union would occupy significant parts of northern Japan.

Truman could have simply waited for the Soviet Union to enter the war but he did not want the USSR to have a claim to participate in the occupation of Japan. Another option (which could have ended the war before August) was to clarify that the emperor would not be held accountable for the war under the policy of unconditional surrender. US secretary of war Stimson recommended this, but secretary of state James Byrnes, who was much closer to Truman, vetoed it.

By dropping the atomic bombs instead, the United States signalled to the world that it considered nuclear weapons to be legitimate weapons of war. Those bombings precipitated the nuclear arms race and they are the source of all nuclear proliferation.

The late Martin J Sherwin was co-author of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J Robert Oppenheimer (Atlantic, 2008)

- Read more | 6 terrible choices people had to make during the Second World War

“Yes. It saved millions of lives in Japan and Asia” – Richard Frank

Dropping the bombs was morally preferable to any other choices available. One of the biggest problems we have is that we can talk about Dresden and the bombing of Hamburg and we all know what the context is: Nazi Germany and what Nazi Germany did. There’s been a great amnesia in the west with respect to what sort of war Japan conducted across Asia-Pacific. Bear in mind that for every Japanese non-combatant who died during the war, 17 or 18 died across Asia-Pacific. Yet you very seldom find references to this and virtually nothing that vivifies it in the way that the suffering at Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been.

With the original invasion strategy negated by radio intelligence revealing the massive Japanese build-up on the planned Kyushu landing areas, Truman’s alternative was a campaign of blockade and bombardment, which would have killed millions of Japanese, mostly non-combatants. For example, in 1946 the food situation would have become catastrophic and there would have been stupendous civilian deaths. It was only because Japan surrendered when it still had a serviceable administrative system – plus American food aid – that saved the country from famine.

- Read more | Stalin’s famine: a brief history of the Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine

Another thing to bear in mind is that while just over 200,000 people were killed in total by the atomic bombs, it is estimated that 300,000–500,000 Japanese people (many of whom were civilians) died or disappeared in Soviet captivity. Had the war continued, that number would have been much higher.

Critics talk about changing the demand for unconditional surrender , but the Japanese government had never put forth a set of terms on which they were prepared to end the war prior to Hiroshima. The inner cabinet ruling the country never devised such terms. When foreign minister Shigenori Togo was told that the best terms Japan could obtain were unconditional surrender with the exception of maintaining the imperial system, Togo flatly rejected them in the name of the cabinet.

The fact is that there was no historical record over the past 2,600 years of Japan ever surrendering, nor any examples of a Japanese unit surrendering during the war. This was where the great American fear lay.

Richard B Frank is a military historian whose books include Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (Random House, 1999)

“No. Better options were discarded for political reasons” – Tsuyoshi Hasegawa

Once sympathetic to the argument that the atomic bomb was necessary, the more research I do, the more I am convinced it was one of the gravest war crimes the US has ever committed. I’ve been to Japan and discovered what happened on the ground in 1945 and it was really horrifying. The radiation has affected people who survived the blast for many years and still today thousands of people suffer the effects.

- Read more | “My God, what have we done?” The moral dilemma of Hiroshima

There were possible alternatives that might have ended the war. Truman could have invited Stalin to sign the Potsdam declaration [in which the USA, Britain and Nationalist China demanded Japanese surrender in July 1945]. The authors of the draft of the declaration believed that if the Soviets joined the war at this time it might lead to Japanese surrender but Truman consciously avoided that option, because he and some of his advisors were apprehensive about Soviet entry. I don’t agree with revisionists who say Truman used the bomb to intimidate the Soviet Union but I believe he used it to force Japan to surrender before they were able to enter the war.

The second option was to alter the demand for unconditional surrender. Some influential advisors within the Truman administration were in favour of allowing the Japanese to keep the emperor system to induce so-called moderates within the Japanese government to work for the termination of the war. However, Truman was mindful of American public opinion, which wanted unconditional surrender as revenge against Pearl Harbor and the Japanese atrocities.

Bearing in mind those atrocities, it’s clear that Japan doesn’t have a leg to stand on when it comes to immoral acts in the war. However, one atrocity does not make another one right. I believe this was the most righteous war the Americans have ever been involved in but you still can’t justify using any means to win a just war.

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa is a professor of history at the University of California at Santa Barbara and the author of Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (Harvard University, Press 2005)

“Yes. The moral failing was Japan’s” – Michael Kort

Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb was the best choice available under the circumstances and was therefore morally justifiable. It was clear Japan was unwilling to surrender on terms even remotely acceptable to the US and its allies, and the country was preparing a defence far more formidable than the US had anticipated.

The choice was not, as is frequently argued, between using an atomic bomb against Hiroshima and invading Japan. No one on the Allied side could say with confidence what would bring about a Japanese surrender, as Japan’s situation had been hopeless for a long time. It was hoped that the shock provided by the bombs would convince Tokyo to surrender, but how many would be needed was an open question. After Hiroshima, the Japanese government had three days to respond before Nagasaki but did not do so. Hirohito and some of his advisers knew Japan had to surrender but were not in a position to get the government to accept that conclusion. Key military members of the government argued that it was unlikely that the US could have a second bomb and, even if it did, public pressure would prevent its use. The bombing of Nagasaki demolished these arguments and led directly to the imperial conference that produced Japan’s offer to surrender.

- Read more | The science behind the bombing of Hiroshima

The absolutist moral arguments (such as not harming civilians) made against the atomic bombs would have precluded many other actions essential to victory taken by the Allies during the most destructive war in history. There is no doubt that had the bomb been available sooner, it would have been used against Germany. There was, to be sure, a moral failing in August 1945, but it was on the part of the Japanese government when it refused to surrender after its long war of conquest had been lost.

Michael Kort is professor of social science at Boston University and author of The Columbia Guide to Hiroshima and the Bomb (Columbia Press, 2007)

This article was first published in the August 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine

HistoryExtra readers George Evans-Hulme and Roy Ceustermans debate...

George Evans-Hulme: Yes, it was justified. The US was, like the rest of the world, soldiering on towards the end of a dark period of human history that had seen the single most costly conflict (in terms of life) in history, and they chose to adopt a stance that seemed to limit the amount of casualties in the war, by significantly shortening it with the use of atomic weapons.

It was certainly a reasonable view for the USA to take, since they had suffered the loss of more than 418,000 lives, both military and civilian. To the top rank of the US military the 135,000 death toll was worth it to prevent the “many thousands of American troops [that] would be killed in invading Japan” – a view attributed to the president himself.

This was a grave consequence taken seriously by the US. Ordering the deployment of the atomic bombs was an abhorrent act, but one they were certainly justified in doing.

Roy Ceustermans : No, the US wasn’t justified. Even secretary of war Henry Lewis Stimson was not sure the bombs were needed to reduce the need of an invasion: “Japan had no allies; its navy was almost destroyed; its islands were under a naval blockade; and its cities were undergoing concentrated air attacks.”

The United States still had many industrial resources to use against Japan, and thus it was essentially defeated. Rear Admiral Tocshitane Takata concurred that B-29s “were the greatest single factor in forcing Japan's surrender”, while Prince Konoye already thought Japan was defeated on 14 February 1945 when he met emperor Hirohito.

A combination of thoroughly bombing blockading cities that were economically dependent on foreign sources for food and raw materials, and the threat of Soviet entry in the war, would have been enough.

The recommendations for the use of the bomb show that the military was more interested in its devastating effect than in preparing the invasion. Therefore the destruction of hospitals and schools etc was acceptable to them.

- Read more | 7 of the best WW2 films

GEH: The USA was more interested in a quick and easy end to the war than causing untold suffering. They had in their hands a weapon that was capable of bringing the war to a swift end, and so they used it.

The atom bombs achieved their desired effects by causing maximum devastation . Just six days after the Nagasaki bombing, the Emperor’s Gyokuon-hōsō speech was broadcast to the nation, detailing the Japanese surrender. The devastation caused by the bombs sped up the Japanese surrender, which was the best solution for all parties.

If the atomic bombs had not had the devastating effect they had, they would have been utterly pointless. They replaced thousands of US bombing missions that would have been required to achieve the same effect of the two bombs that, individually, had the explosive power of the payload of 2,000 B-29s. This freed up resources that could be utilised for the war effort elsewhere.

RC: After the bloody battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa , the death toll on both sides was high, and the countries’ negative view of one other became almost unbridgeable, says J Samuel Walker in Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and The Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan . Therefore, the US created unconditional terms of surrender, knowingly going against the Japanese ethic of honour and against the institute of the emperor, whom most Americans probably wanted dead.

Consequently, the use of the atomic bomb became a way to avenge America's fallen soldiers while also keeping the USSR in check in Europe. The Japanese civilian casualties did not matter in this strategy. Also, it did not prevent the Cold War , as the USSR was just a few years behind on a-bomb research.

At the time, revenge, geopolitics and an expensive project that could not be allowed to simply rust away, meant the atomic bomb had to be hastily deployed “in the field” in order to see its power and aftermath – though little was known about radiation and its effects on humans.

GEH: Admittedly, the US did use the atom bomb to keep the USSR in line, and for that it served its purpose. It may not have stopped the Soviets developing their own nuclear device, but that’s not what it was intended for. It was used as a deterrent to keep the (sometimes uneasy) peace between the US and the USSR, and it achieved that. There are no cases of a direct, all-out war between the US and the Soviets that can be attributed to the potentially devastating effects of atomic weaponry.

The atomic bombs certainly established US dominance immediately after the Second World War – the destructive power it possessed meant that it remained uncontested as the world’s greatest power until the Soviets developed their own weapon, four years after the deployment at Nagasaki. It is certainly true that Stalin and the Soviets tried to test US dominance, but even into the 1960s the US generally came out on top.

RC: The price to keep the USSR in check was steep: the use of a weapon of mass destruction that caused around 200,000 deaths (most of them civilians) and massive suffering through radiation . However, it did not stop the USSR from creating the same weapon within four years.

It might be argued that, following the explosions, Japan virtually disappeared from the world stage while the USSR viewed the bombing as an incentive to acquire the same weaponry in order to retaliate in equal force if the atomic bomb was ever used again. Considering the tension between the two countries, a similar attack with tens of thousands of civilian casualties would have created a nuclear apocalypse .

If the US had organised a demonstration, as they had briefly considered, the USSR would still have responded in the same manner, while Japan – which had made clear overtures for a (un)conditional surrender – could have been spared. Furthermore, by postponing the use of the bomb, scientists would have had time to understand the test results, meaning further anguish, like the Bikini Atoll [a huge US hydrogen bomb test in 1954 that had major consequences for the geology and natural environment, and on the health of those who were exposed to radiation] could have been avoided.

GEH: The large civilian death toll that resulted from the bombings can be seen as a small price to pay by the United States in return for their assertion of dominance on the world stage.

The USSR’s development of an atomic weapon had been underway since 1943, and so their quest for nuclear devices cannot be solely attributed to the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It should also be considered that the Soviets’ rapid progress in creating an atom bomb was not exclusively down to their desire to compete with the United States, but from spies passing them US secrets.

Postponing the use of the atom bomb would only have prolonged the war and potentially created an even worse fate for the people of Japan, with an estimated five to 10 million Japanese fatalities – a number higher than some estimates for the entire Soviet military in the Second World War.

Ultimately, the atomic bombs did what they were designed to do. They created such a high level of devastation that the Japanese felt they had no option but to surrender unconditionally to the United States, hence resulting in US victory and the end of the Second World War .

RC: Of course civilian casualties of another nation would have been acceptable to the USA. Japan had made clear overtures to peace, but cultural differences made this nearly impossible (the shame of unconditional surrender goes against their code of honour).

The determination to use an expensive bomb instead of letting it rust away; the desire to find out how devastating it was and the opportunity to use the bomb as a strong showcase of US supremacy, made Japan the ideal target.

Obviously, the USSR would eventually succeed in creating the a-bomb. Therefore, making Hiroshima & Nagasaki the example of the tremendous power of the bombs would make it clear to the USSR that they too needed such weapons to defend themselves.

Moreover, other countries claimed the right of nuclear weapons to defend their citizens. Consequently, the tragic bombings became the example of an arm’s race instead of peace.

Furthermore, since Japan was already on the brink of collapse the bombing was unnecessary, and peace talks would have taken place within a decent time frame (even after the cancelled Hawaii summit). The millions of deaths calculated by Operation Downfall [the codename for the Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of the Second World War, which was abandoned when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki] actually show that only desperation and honour stood between Japan and unconditional surrender.

George Evans-Hulme has a passion for military and political history, and enjoys visiting historical sites across the UK.

Roy Ceustermans has a master's degree in the history of the Catholic Church, an advanced master's degree on the historical expansion, exchange and globalisation of the world, and a master’s degree in management.

Don't miss out on a chance to get a hardback and signed copy of Zeinab Badawi 's latest book when you subscribe to BBC History Magazine

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

Save 40% + Zeinab Badawi's latest book

Subscribe today!

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

The atomic bombings of hiroshima and nagasaki.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Hiroshima August 6, 1945

0809 Air raid sirens begin in Hiroshima. 0912 Enola Gay bombardier Thomas Ferebee takes control of the aircraft as the bombing run begins. 0914:17 Hiroshima’s Aioi Bridge, the target point, comes into view. A 60-second timer commences. 0915:15 (8:15 am in Hiroshima) Ferebee announces “Bomb away” as Little Boy is released from 31,060 feet (9467m). 0916:02 (8:16:02 am in Hiroshima) After falling from the Enola Gay for 43 seconds, the Little Boy atomic bomb detonates 1,968 feet above Hiroshima, 550 feet (167.64 m) from the Aioi Bridge. Nuclear fission begins in 0.15 microseconds.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

0916:03 (8:16:03 am in Hiroshima, one second after detonation). The fireball reaches maximum size, 900 feet (274.32m) in diameter. The mushroom cloud begins to form. As temperatures on the ground reach 7,000 degrees Fahrenheit (3871 Celsius), buildings melt and fuse together, human and animal tissue is vaporized. The blast wave travels at 984 miles per hour (1583.59 kph) in all directions, demolishing over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings in a massive, expanding firestorm. Eighty thousand people are instantly killed or grievously wounded. Over 100,000 more will die from the bomb’s effects in the coming months.

1055 The U.S. intercepts a Japanese message: “a violent, large special-type bomb, giving the appearance of magnesium.”

1458 The Enola Gay lands at Tinian. The mission has lasted twelve hours. 1500 Tokyo news agencies report an attack on Hiroshima. Very few details are given.

Nagasaki August 9, 1945

Times are in Tinian Time Unless Otherwise Noted, One Hour Ahead of Nagasaki

0347 The B-29 Superfortress Bockscar lifts off from Tinian with the plutonium bomb Fat Man aboard. The target is the Japanese city of Kokura. 0351 and 0353 Support planes the Great Artiste and Big Stink lift off from Tinian. Two weather-spotting aircraft, the Enola Gay and Laggin’ Dragon are already airborne. 0400 Cmdr. Fred Ashworth arms Fat Man atomic bomb. 1044 Bockscar arrives at Kokura. Haze makes it too difficult to locate the drop point. 1132 Major Charles Sweeney, Bockscar’s pilot, makes the decision to turn for the secondary target, Nagasaki, 95 miles south of Kokura. 1158 Upon arrival over Nagasaki, cloud cover allows for only one drop point, several miles from the intended target. Bombardier Kermit Beahan releases the Fat Man atomic bomb. 1202 (11:02am in Nagasaki) Fat Man explodes 1,650 feet (502.92m) above the city. Between 40,000-75,000 people die instantly. The bomb creates a blast radius one mile wide (1609.34m) . The geography of Nagasaki prevents destruction on the same scale as Hiroshima, yet nearly half the city is obliterated. 2230 All aircraft return to Tinian.

Bibliography

- “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing Timeline”, Atomic Heritage Foundation, accessed August 4, 2020, https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombing-timeline

You Might Also Like

- manhattan project national historical park

- manhattanproject1945

- manhattan project

- atomic bomb

- world war ii

- atomic bomb survivors

Manhattan Project National Historical Park

Last updated: April 4, 2023

Home — Essay Samples — War — Atomic Bomb — Atomic Bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Atomic Bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Categories: Atomic Bomb Hiroshima

About this sample

Words: 1237 |

Published: Apr 29, 2022

Words: 1237 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Works Cited

- Alperovitz, G. (1995). The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth. Vintage.

- Bernstein, B. J. (1991). Understanding the Atomic Bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory. Journal of Military History, 55(4), 585-600.

- Ham, P. (2011). Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath. St. Martin's Griffin.

- Hersey, J. (1985). Hiroshima. Vintage.

- Hasegawa, T. (2006). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Harvard University Press.

- Newman, R. J. (1995). Truman and the Hiroshima Cult. Michigan Quarterly Review, 34(3), 492-513.

- Rhodes, R. (1995). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon & Schuster.

- Walker, J. S. (2017). Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan. University of North Carolina Press.

- Wainstock, D. D. (1996). The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Praeger Publishers.

- Zinn, H. (2015). A People's History of the United States. Harper Perennial.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: War History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 626 words

3 pages / 1286 words

2 pages / 830 words

4 pages / 1646 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Atomic Bomb

The essay delves into the significant impact of the atomic bomb on global politics and warfare, particularly as a catalyst for the Cold War. It explores how the bomb fueled the nuclear arms race, influenced diplomatic [...]

The atomic bomb, a devastating creation of science and engineering, has cast a long shadow over the world since its use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. In 2023-2024, we continue to ponder the atomic bomb's past and present [...]

The advent of the atomic bomb in 1945 marked a watershed moment in human history, ushering in an era of unprecedented destructive power and fundamentally altering the dynamics of warfare. The sheer destructive force of these [...]

The mushroom clouds that rose over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 cast a long and enduring shadow over human society, forever altering the collective perception of security and ushering in an era of unprecedented existential [...]

In the 1940’s, the world was at war between Germany, Italy, Japan and the Allies. This whole war could have been very catastrophic. Nazi Germany was planning on taking over the world. During the war, a brave and smart group of [...]

In recent years, a wide array of new technologies have entered the modern battlefield, giving rise to new means and methods of warfare, such as cyber-attacks, armed drones, and robots, including autonomous weapons. While there [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay on Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombing

Students are often asked to write an essay on Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombing in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombing

The atomic bombings.

In August 1945, during World War II, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. The first bomb fell on Hiroshima on August 6, and the second hit Nagasaki three days later. These bombings were the first and only use of nuclear weapons in war.

Impact on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The bombs caused massive destruction. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were left in ruins, with buildings destroyed and many people killed instantly. Those who survived faced severe injuries and sickness due to radiation.

Why the US Chose to Bomb

The United States wanted to end the war quickly and save lives. Leaders believed that using the bombs would force Japan to surrender without invading Japanese land, which could have caused more deaths.

Aftermath and Surrender

After the bombings, Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945. This brought an end to World War II. The bombings changed the world, showing the devastating power of nuclear weapons and starting a new era of warfare.

250 Words Essay on Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombing

The bombing of hiroshima and nagasaki.

In August 1945, during World War II, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was the first time atomic bombs were used in war. The bombings led to the end of World War II but caused great destruction and loss of life.

Why the Bombs Were Dropped

The United States wanted to end the war quickly and save lives by avoiding a land invasion of Japan. Leaders believed that the shock of the bombings would force Japan to surrender. After warning Japan, the US dropped the first bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, and the second on Nagasaki on August 9.

The Destruction Caused

The bomb on Hiroshima killed about 70,000 people instantly, and thousands more died later from injuries and radiation. Nagasaki faced similar horrors, with around 40,000 people dying on the first day. Buildings were destroyed, and survivors suffered from severe burns and radiation sickness.

Aftermath and Healing

Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, marking the end of World War II. The bombings left deep scars, with survivors facing long-term health problems. Over time, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were rebuilt, and they became symbols of peace and the need to control nuclear weapons.

Remembering the Event

Today, people remember the bombings to understand the terrible power of nuclear weapons. Museums in both cities teach visitors about the bombings and the importance of peace. The world hopes that such destruction will never happen again.

500 Words Essay on Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombing

In August 1945, during World War II, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was the first and only time in history that nuclear bombs were used in war. The bombings led to Japan surrendering, which ended World War II. These events are important to remember because they changed the world forever.

Why Did the US Drop the Bombs?

The United States wanted to end the war quickly and save lives. American leaders thought that if they could make Japan surrender by showing the power of these bombs, they could avoid a long and deadly battle. They also wanted to show their strength to the Soviet Union, which was becoming a powerful country.

Hiroshima: The First Atomic Bomb

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the US bomber Enola Gay flew over Hiroshima, a city in Japan. At 8:15 AM, the bomb named “Little Boy” was dropped. It exploded above the city, creating a huge fireball and destroying everything in its path. Around 70,000 people died instantly from the blast and the heat. Many more were hurt and would suffer from the effects of the radiation for years.

Nagasaki: The Second Attack

Three days after Hiroshima, on August 9, 1945, another bomb named “Fat Man” was dropped on the city of Nagasaki. This bomb also caused massive destruction and death. About 40,000 people died right away, and many others were injured or became sick from the radiation.

The Aftermath of the Bombings

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused terrible suffering. People who were near the bombs when they exploded were killed or badly hurt. Those who survived faced sicknesses caused by the radiation, like cancer. The cities were ruined, and it took many years to rebuild them.

The bombs also made countries think about how dangerous nuclear weapons are. After the war, countries started to make more bombs, but they also talked about how to control them so they wouldn’t be used again.

Remembering the Bombings

Every year, people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki remember the bombings. They have ceremonies to think about peace and to remember the people who died or were hurt. These events remind us of the terrible power of nuclear weapons and why it’s important to work for peace in the world.

In conclusion, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were a sad part of history that showed how destructive war can be. It’s important to learn about these events so that they never happen again. By remembering the past, we can hope for a future where people live together in peace.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Driverless Cars

- Essay on Driving

- Essay on Dropping Out Of High School

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: a Historical Perspective

This essay about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki examines the complex historical, ethical, and geopolitical contexts surrounding the events. It discusses the rationale behind President Truman’s decision, the arguments for and against the bombings, and their profound moral implications. The essay also reflects on the legacy of nuclear terror and the need for moral clarity and empathy in evaluating these catastrophic actions.

How it works

In the vast expanse of human history, few events are as entangled and contentious as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These events, shrouded in a moral labyrinth, compel us to wade through layers of historical context, ethical considerations, and geopolitical complexities to evaluate the justification, if any, for such catastrophic actions.

Rewinding to the turmoil of World War II, we witness a world consumed by the flames of conflict. The Axis powers, with their authoritarian regimes, had cast a long shadow over the globe, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake.

In the Pacific theater, the relentless clash between the Allied forces and Imperial Japan had reached a fever pitch of violence and desperation.

It was in this backdrop of chaos and carnage that the decision to deploy the atomic bomb was made. On that fateful August day, the Enola Gay soared through the skies, carrying a weapon of unprecedented power and devastation. With a deafening roar, “Little Boy” descended upon Hiroshima, forever altering the trajectory of history.

The rationale behind President Truman’s monumental decision is a complex tapestry woven with threads of pragmatism, ideology, and fear. Supporters argue that the bombings were a necessary evil, a calculated move aimed at hastening the end of the war and saving lives. They point to the grim prospect of a prolonged invasion of Japan, with its staggering human cost, as justification for the unthinkable.

Yet, amidst the ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, dissenting voices cry out in sorrow. Critics denounce the bombings as a blatant violation of the principles of just war and a betrayal of our shared humanity. They question the moral calculus that justifies the deliberate targeting of civilian populations and the immense suffering inflicted upon innocent men, women, and children.

Furthermore, critics dispute the notion that the bombings were the decisive factor in Japan’s surrender, highlighting a constellation of political, social, and strategic elements at play. The specter of Soviet intervention, the ravages of conventional bombing, and the erosion of Japanese morale all contributed to the collapse of Imperial Japan, they argue, making the atomic bombings unnecessary and morally indefensible.

In the shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world grapples with the legacy of nuclear terror. The bombings opened a Pandora’s box of existential dread, sparking a nuclear arms race that threatened the very fabric of civilization. As the Cold War loomed, the specter of mutually assured destruction cast a pall over humanity, underscoring the fragility of peace in a world bristling with nuclear weapons.

As we sift through the ashes of history, we face profound moral and ethical questions that resist easy answers. How do we balance the imperatives of national security with the imperative of human security? How do we navigate the perilous waters of war without losing sight of our common humanity?

In the final analysis, evaluating the justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings requires more than historical hindsight—it demands moral clarity and ethical courage. It urges us to confront the shadows of the past with humility and empathy, to recognize the suffering of the innocent, and to strive for a future where the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are forever consigned to the annals of history.

Cite this page

Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: A Historical Perspective. (2024, May 28). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/assessing-the-justification-of-the-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombings-a-historical-perspective/

"Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: A Historical Perspective." PapersOwl.com , 28 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/assessing-the-justification-of-the-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombings-a-historical-perspective/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: A Historical Perspective . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/assessing-the-justification-of-the-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombings-a-historical-perspective/ [Accessed: 25 Oct. 2024]

"Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: A Historical Perspective." PapersOwl.com, May 28, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/assessing-the-justification-of-the-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombings-a-historical-perspective/

"Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: A Historical Perspective," PapersOwl.com , 28-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/assessing-the-justification-of-the-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombings-a-historical-perspective/. [Accessed: 25-Oct-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Assessing the Justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: A Historical Perspective . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/assessing-the-justification-of-the-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombings-a-historical-perspective/ [Accessed: 25-Oct-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Reasons why Bombing Japan was not justified Essay

Introduction, works cited.

The dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are still one of the most controversial happenings in recent history. Historians have passionately debated whether the bombings were essential, the effect that they had in ending the war in the Pacific Region, and what other alternatives were on hand for the United States.

These very same questions were also debatable during that time, as American decision makers deliberated on how to put to use powerful new technology and what the long-term impact of atomic weaponry would be on the Japanese (Hasegawa 96). This essay presents a debate on reasons why the U.S. was not justified in using the atomic bomb on Japan.

Most historians who have been taking part in the debate on how World War II ended have based much of their focus on why the U.S. decided to drop the atomic bomb. Despite the much emphasis placed on this matter, there has been little attention directed on the role played by the Japanese in ending the war.

Even less information is available on soviet-decision-making and their joining the war against Japan. One of the major obstacles, which were overcome only recently, was the absence of a historian who was fluent in English, Japanese and Russian to enable him to examine the major materials, which included government, military, and intelligence memos and reports in all the three languages. This explains in part why most of the available literature on the subject only touches on the American side of the story.

One of the reasons why bombing Japan was not justified is because America had other options, which they could have used to compel Japan to surrender. In his 2005 milestone study titled Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan , historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa critically examines the threefold wartime relationship between America, Japan, and the Soviet Union.

What comes out from this careful study is the fact that America had other options that they could have pursued instead of the bombings but which they chose to ignore. According to Hasegawa (100), the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had indicated to America that he would attack Japan on 15 August 1945.

This meant that America had up to 15 th August to force Japan to surrender in order to prevent the Soviet union from joining the war something that would make Truman and his government to appear weak. Contrary to the claim that Americans used the bomb as a last resort, Hasegawa disagrees and claims that the early August date was chosen to counter the Soviets’ impeding attack in order to prevent them from joining the war.

In fact, the diligent research done by Hasegawa dispels the notion that the bombings weakened Japan’s position thus leading to their surrender.

According to the historian, the myth that the bombings weakened Japan’s will to fight and that they saved both Japanese and American soldiers is only meant to justify Truman’s decision and help in easing the conscience of the American people. According to Hasegawa, this myth lacks any historical backing since there is enough evidence to show that there were other alternatives besides the use of the bombs but Truman and his administration chose to ignore them.

Historians claim that Truman’s main worry was that allowing Stalin to enter the war would be an important strategic gain for him and this would pose a big threat to American interests in the region. With a deadline to beat, the only option that remained for Truman and his administration was to use the atomic bomb (Hasegawa 101).

Although Japan had not yet given a public indication that it intended to surrender, insiders knew that the country could not continue with the war and surrender was imminent.

This admission is contained in intelligence reports showing that Truman was privy to information that Japan had abandoned its goal of victory and was instead planning on how to harmonize its national pride with losing the war. With this kind of information, it is clear that America had no justification whatsoever to use the bombs since it was only a matter of time before the Japanese admitted defeat.

The second reason that makes the American bombing unjustified is the deeply flawed casualty claims. As it is, the exact number of Allied and Japanese lives that were likely to be lost during the intended invasion remains unknown. However, it is evident that those who supported the bombing have escalated the prediction of those who could have died from the earlier prediction of 45,000 given by the U.S. War Department.

Ten years after the bombings, Truman claimed that George Marshall feared losing close to a half million soldiers if the war was not brought to an abrupt close. This contradicted the claims by Stimson the Secretary of War who two years after the war had claimed that over a million people were dead, wounded, or missing.

In a 1991 address to congress, George Bush claimed that Truman’s decision to drop the bomb ‘spared’ millions of American lives. Four years after the claims by Bush, a crewmember of Bock’s car, the plane that dropped one of the bombs stated that the bombing preserved the lives of over six million people.

Over the years, historians have provided evidence to show that the casualty figures offered by Truman and his bombing supporters were seriously flawed. One historian claimed that the people who supported the high casualty claims relied upon strained readings and omitted crucial material, which in effect limited their research and cast a shadow of doubt on their findings.

Hasegawa and other anti-bombing historians did not refute the claim that Truman was concerned at the possibility of America losing many lives during the invasion, but the projected numbers were way below the exaggerated figures provided after the war to rationalize the bombings.

Such inflated figures, along with Japan’s presumed rejection of surrendering is usually a part of the debate on why the atomic bombs were necessary but from the proffered evidence, these claims are highly questionable.

Another reason to prove that the bombing was not justified is derived from looking at the real reasons why Japan surrendered. According to political analysts, postwar interviews with numerous Japanese military and civilian leaders showed that Japan could have given in before November 1, which is the date that the U.S. had planned to invade the country.

This was not because Japan was afraid of atomic bombs or the impeding Soviet entry but because they had no reason to continue fighting in a war, which they were certain to lose. This conclusion definitely supports the view that the bombings were not in any way necessary to end the war and their use was therefore unjustified.