- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Story of Genie Wiley

What her tragic story revealed about language and development

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Who Was Genie Wiley?

Why was the genie wiley case so famous, did genie learn to speak, ethical concerns.

While there have been a number of cases of feral children raised in social isolation with little or no human contact, few have captured public and scientific attention, like that of Genie Wiley.

Genie spent almost her entire childhood locked in a bedroom, isolated, and abused for over a decade. Her case was one of the first to put the critical period theory to the test. Could a child reared in utter deprivation and isolation develop language? Could a nurturing environment make up for a horrifying past?

In order to understand Genie's story, it is important to look at what is known about her early life, the discovery of the abuse she had endured, and the subsequent efforts to treat and study her.

Early Life (1957-1970)

Genie's life prior to her discovery was one of utter deprivation. She spent most of her days tied naked to a potty chair, only able to move her hands and feet. When she made noise, her father would beat her. The rare times her father did interact with her, it was to bark or growl. Genie Wiley's brother, who was five years older than Genie, also suffered abuse under their father.

Discovery and Study (1970-1975)

Genie's story came to light on November 4, 1970, in Los Angeles, California. A social worker discovered the 13-year old girl after her mother sought out services for her own health. The social worker soon discovered that the girl had been confined to a small room, and an investigation by authorities quickly revealed that the child had spent most of her life in this room, often tied to a potty chair.

A Genie Wiley documentary was made in 1997 called "Secrets of the Wild Child." In it, Susan Curtiss, PhD, a linguist and researcher who worked with Genie, explained that the name Genie was used in case files to protect the girl's identity and privacy.

The case name is Genie. This is not the person's real name, but when we think about what a genie is, a genie is a creature that comes out of a bottle or whatever but emerges into human society past childhood. We assume that it really isn't a creature that had a human childhood.

Both parents were charged with abuse , but Genie's father died by suicide the day before he was due to appear in court, leaving behind a note stating that "the world will never understand."

The story of Genie's case soon spread, drawing attention from both the public and the scientific community. The case was important, said psycholinguist and author Harlan Lane, PhD, because "our morality doesn’t allow us to conduct deprivation experiments with human beings; these unfortunate people are all we have to go on."

With so much interest in her case, the question became what should be done to help her. A team of psychologists and language experts began the process of rehabilitating Genie.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) provided funding for scientific research on Genie’s case. Psychologist David Rigler, PhD, was part of the "Genie team" and he explained the process.

I think everybody who came in contact with her was attracted to her. She had a quality of somehow connecting with people, which developed more and more but was present, really, from the start. She had a way of reaching out without saying anything, but just somehow by the kind of look in her eyes, and people wanted to do things for her.

Genie's rehabilitation team also included graduate student Susan Curtiss and psychologist James Kent. Upon her initial arrival at UCLA, Genie weighed just 59 pounds and moved with a strange "bunny walk." She often spat and was unable to straighten her arms and legs. Silent, incontinent, and unable to chew, she initially seemed only able to recognize her own name and the word "sorry."

After assessing Genie's emotional and cognitive abilities, Kent described her as "the most profoundly damaged child I've ever seen … Genie's life is a wasteland." Her silence and inability to use language made it difficult to assess her mental abilities, but on tests, she scored at about the level of a 1-year-old.

Genie Wiley's Rehabilitation and the Forbidden Experiment

She soon began to rapidly progress in specific areas, quickly learning how to use the toilet and dress herself. Over the next few months, she began to experience more developmental progress but remained poor in areas such as language. She enjoyed going out on day trips outside of the hospital and explored her new environment with an intensity that amazed her caregivers and strangers alike.

Curtiss suggested that Genie had a strong ability to communicate nonverbally , often receiving gifts from total strangers who seemed to understand the young girl's powerful need to explore the world around her.

Psychiatrist Jay Shurley, MD, helped assess Genie after she was first discovered, and he noted that since situations like hers were so rare, she quickly became the center of a battle between the researchers involved in her case. Arguments over the research and the course of her treatment soon erupted. Genie occasionally spent the night at the home of Jean Butler, one of her teachers.

After an outbreak of measles, Genie was quarantined at her teacher's home. Butler soon became protective and began restricting access to Genie. Other members of the team felt that Butler's goal was to become famous from the case, at one point claiming that Butler had called herself the next Anne Sullivan, the teacher famous for helping Helen Keller learn to communicate.

Genie was partially treated like an asset and an opportunity for recognition, significantly interfering with their roles, and the researchers fought with each other for access to their perceived power source.

Eventually, Genie was removed from Butler's care and went to live in the home of psychologist David Rigler, where she remained for the next four years. Despite some difficulties, she appeared to do well in the Rigler household. She enjoyed listening to classical music on the piano and loved to draw, often finding it easier to communicate through drawing than through other methods.

After Genie was discovered, a group of researchers began the process of rehabilitation. However, this work also coincided with research to study her ability to acquire and use language. These two interests led to conflicts in her treatment and between the researchers and therapists working on her case.

State Custody (1975-Present)

NIMH withdrew funding in 1974, due to the lack of scientific findings. Linguist Susan Curtiss had found that while Genie could use words, she could not produce grammar. She could not arrange these words in a meaningful way, supporting the idea of a critical period in language development.

Rigler's research was disorganized and largely anecdotal. Without funds to continue the research and care for Genie, she was moved from the Riglers' care.

In 1975, Genie returned to live with her birth mother. When her mother found the task too difficult, Genie was moved through a series of foster homes, where she was often subjected to further abuse and neglect .

Genie’s situation continued to worsen. After spending a significant amount of time in foster homes, she returned to Children’s Hospital. Unfortunately, the progress that had occurred during her first stay had been severely compromised by the subsequent treatment she received in foster care. Genie was afraid to open her mouth and had regressed back into silence.

Genie’s birth mother then sued the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and the research team, charging them with excessive testing. While the lawsuit was eventually settled, it raised important questions about the treatment and care of Genie. Did the research interfere with the girl's therapeutic treatment?

Psychiatrist Jay Shurley visited her on her 27th and 29th birthdays and characterized her as largely silent, depressed , and chronically institutionalized. Little is known about Genie's present condition, although an anonymous individual hired a private investigator to track her down in 2000 and described her as happy. But this contrasts with other reports.

Genie Wiley Today

Today, Genie Wiley's whereabouts are unknown; though, if she is still living, she is presumed to be a ward of the state of California, living in an adult care home. As of 2024, Genie would be 66-67 years old.

Part of the reason why Genie's case fascinated psychologists and linguists so deeply was that it presented a unique opportunity to study a hotly contested debate about language development.

Essentially, it boils down to the age-old nature versus nurture debate. Does genetics or environment play a greater role in the development of language?

Nativists believe that the capacity for language is innate, while empiricists suggest that environmental variables play a key role. Nativist Noam Chomsky suggested that acquiring language could not be fully explained by learning alone.

Instead, Chomsky proposed that children are born with a language acquisition device (LAD), an innate ability to understand the principles of language. Once exposed to language, the LAD allows children to learn the language at a remarkable pace.

Critical Periods

Linguist Eric Lenneberg suggests that like many other human behaviors, the ability to acquire language is subject to critical periods. A critical period is a limited span of time during which an organism is sensitive to external stimuli and capable of acquiring certain skills.

According to Lenneberg, the critical period for language acquisition lasts until around age 12. After the onset of puberty, he argued, the organization of the brain becomes set and no longer able to learn and use language in a fully functional manner.

Genie's case presented researchers with a unique opportunity. If given an enriched learning environment, could she overcome her deprived childhood and learn language even though she had missed the critical period?

If Genie could learn language, it would suggest that the critical period hypothesis of language development was wrong. If she could not, it would indicate that Lenneberg's theory was correct.

Despite scoring at the level of a 1-year-old upon her initial assessment, Genie quickly began adding new words to her vocabulary. She started by learning single words and eventually began putting two words together much the way young children do. Curtiss began to feel that Genie would be fully capable of acquiring language.

After a year of treatment, Genie started putting three words together occasionally. In children going through normal language development, this stage is followed by what is known as a language explosion. Children rapidly acquire new words and begin putting them together in novel ways.

Unfortunately, this never happened for Genie. Her language abilities remained stuck at this stage and she appeared unable to apply grammatical rules and use language in a meaningful way. At this point, her progress leveled off and her acquisition of new language halted.

While Genie was able to learn some language after puberty, her inability to use grammar (which Chomsky suggests is what separates human language from animal communication) offers evidence for the critical period hypothesis.

Of course, Genie's case is not so simple. Not only did she miss the critical period for learning language, but she was also horrifically abused. She was malnourished and deprived of cognitive stimulation for most of her childhood.

Researchers were also never able to fully determine if Genie had any pre-existing cognitive deficits. As an infant, a pediatrician had identified her as having some type of mental delay. So researchers were left to wonder whether Genie had experienced cognitive deficits caused by her years of abuse or if she had been born with some degree of intellectual disability.

There are many ethical concerns surrounding Genie's story. Arguments among those in charge of Genie's care and rehabilitation reflect some of these concerns.

"If you want to do rigorous science, then Genie's interests are going to come second some of the time. If you only care about helping Genie, then you wouldn't do a lot of the scientific research," suggested psycholinguist Harlan Lane in the NOVA documentary focused on her life.

In Genie's case, some of the researchers held multiple roles of caretaker-teacher-researcher-housemate. which, by modern standards, we would deem unethical. For example, the Riglers benefitted financially by taking Genie in (David received a large grant and was released from certain duties at the children's hospital without loss of pay). Butler also played a role in removing Genie from the Riglers' home, filing multiple complaints against him.

While Genie's story may be studied for its implications in our understanding of language acquisition and development, it is also a case that will continue to be studied over its serious ethical issues.

"I think future generations are going to study Genie's case not only for what it can teach us about human development but also for what it can teach us about the rewards and the risks of conducting 'the forbidden experiment,'" Lane explained.

Bottom Line

Genie Wiley's story perhaps leaves us with more questions than answers. Though it was difficult for Genie to learn language, she was able to communicate through body language, music, and art once she was in a safe home environment. Unfortunately, we don't know what her progress could have been had adequate care not been taken away from her.

Ultimately, her case is so important for the psychology and research field because we must learn from this experience not to revictimize and exploit the very people we set out to help. This is an important lesson because Genie's original abuse by her parents was perpetuated by the neglect and abandonment she faced later in her life. We must always strive to maintain objectivity and consider the best interest of the subject before our own.

Frequently Asked Questions

Genie, now in her 60s, is believed to be living in an adult care facility in California. Efforts by journalists to learn more about her location and current condition have been rejected by authorities due to confidentiality rules. Curtiss has also reported attempting to contact Genie without success.

Along with her husband, Irene Wiley was charged with abuse, but these charges were eventually dropped. Irene was blind and reportedly mentally ill, so it is believed that Genie's father was the child's primary caretaker. Genie's father, Clark Wiley, also abused his wife and other children. Two of the couple's children died in infancy under suspicious circumstances.

Genie's story suggests that the acquisition of language has a critical period of development. Her case is complex, however, since it is unclear if her language deficits were due to deprivation or if there was an underlying mental disability that played a role. The severe abuse she experienced may have also affected her mental development and language acquisition.

Collection of research materials related to linguistic-psychological studies of Genie (pseudonym) (collection 800) . UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Schoneberger T. Three myths from the language acquisition literature . Anal Verbal Behav. 2010;26(1):107–131. doi:10.1007/bf03393086

APA Dictionary of Psychology. Language acquisition device . American Psychological Association.

Vanhove J. The critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition: A statistical critique and a reanalysis . PLoS One . 2013;8(7):e69172. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069172

Carroll R. Starved, tortured, forgotten: Genie, the feral child who left a mark on researchers . The Guardian .

James SD. Raised by a tyrant, suffering a sibling's abuse . ABC News .

NOVA . The secret of the wild child [transcript]. PBS,

Pines M. The civilizing of Genie. In: Kasper LF, ed., Teaching English Through the Disciplines: Psychology . Whittier.

Rolls G. Classic Case Studies in Psychology (2nd ed.). Hodder Arnold.

Rymer R. Genie: A Scientific Tragedy. Harper-Collins.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment (Explained)

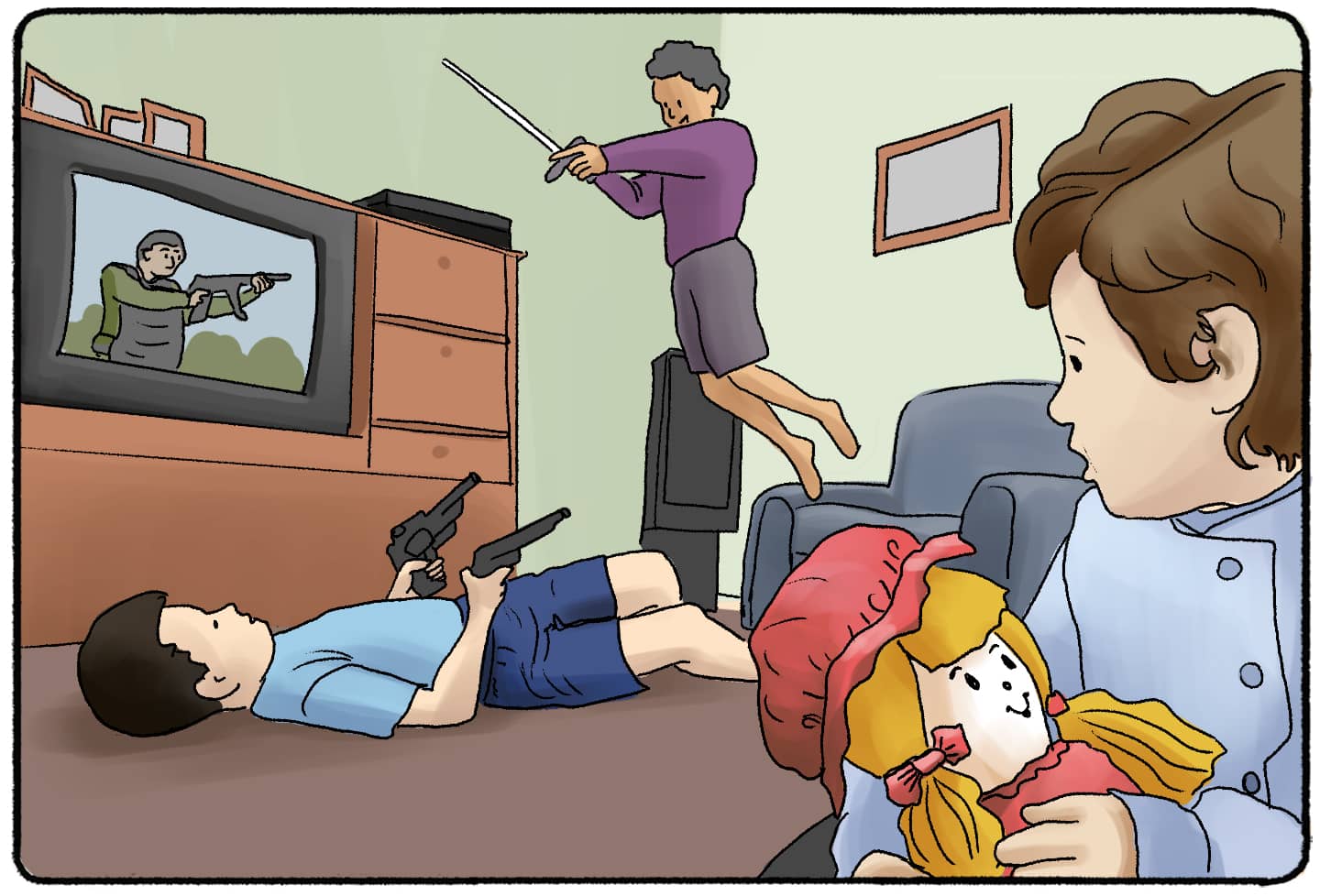

The Bobo Doll Experiment was a study by Albert Bandura to investigate if social behaviors can be learned by observing others in the action. According to behaviorists, learning occurs only when a behavior results in rewards or punishment. However, Bandura didn't believe the framework of rewards and punishments adequately explained many aspects of everyday human behavior.

According to the Social Learning Theory, people learn most new skills through modeling, imitation, and observation. Bandura believed that people could learn by observing how someone else is rewarded or penalized instead of engaging in the action themselves.

In the hit television show Big Little Lies, tensions run high as an unknown child is accused of choking another student. The child is revealed as Max throughout the series (spoiler alert!). Max has an abusive father, and once Max’s mother realizes that her child is learning behaviors from her husband, she decides to take action.

This cycle of abuse is sad but extremely common. Many abusers were abused themselves or grew up in an abusive household. These ideas seem obvious, but in the mid-20th century, evidence that supports these ideas was becoming known.

What is the Bobo Doll Experiment?

In 1961, Albert Bandura conducted the Bobo doll experiment at Stanford University. He placed children in a room with an adult, toys, and a five-foot Bobo Doll. (Bobo Dolls are large inflatable clowns shaped like a bowling ball, so they roll upward if punched or knocked down.)

Who Conducted the Bobo Doll Experiment?

This experiment made Albert Bandura one of the most renowned psychologists in the history of the world. He is now listed in the ranks of Freud and B.F. Skinner, the psychologist who developed the theory of operant conditioning .

How Was The Bobo Doll Experiment Conducted?

Let’s start by discussing Bandura’s first Bobo doll experiment from 1961. Bandura conducted the experiment in three parts: modeling, aggression arousal, and a test for delayed imitation.

Stage 1: Modeling

The study was separated into three groups, including a control group. An aggressive adult behavior model was shown to one group, a non-aggressive adult behavior model to another, and no behavior models were shown to the third group. In the group with the aggressive adult, some models chose to hit the Bobo doll over the head with a mallet.

The group with a nonaggressive adult simply observed the model playing with blocks, coloring, or doing non-aggressive activities.

Stage 2: Aggression Arousal

After 10 minutes of being in the room with the model, the child was taken into another room. This room had attractive toys; the researchers briefly allowed the children to play with the toys of their choice. Once the child was engaged in play, the researchers removed the toys from the child and took them into yet another room. It’s easy to guess that the children were frustrated, but the researchers wanted to see how they would release that frustration.

Stage 3: Test For Delayed Imitation

The third room contained a set of “aggressive” and “non-aggressive toys.” The room also had a Bobo doll. Researchers watched and recorded each child’s behavior through a one-way mirror.

So what happened?

As you can probably guess, the children who observed the adults hitting the Bobo doll were more likely to take their frustration out on the Bobo doll. They kicked, yelled at, or even used the mallet to hit the doll. The children who observed the non-aggressive adults tended to avoid the Bobo doll and take their frustration out without aggression or violence.

The Second Bobo Doll Experiment

Albert Bandura did not stop with the 1961 Bobo doll experiment. Two years later, he conducted another experiment with a Bobo doll. This one combined the ideas of modeling with the idea of conditioning. Were people genuinely motivated by consequences, or was there something more to their behavior and attitudes?

In this experiment, Bandura showed children a video of a model acting aggressively toward the Bobo doll. Three groups of children individually observed a different final scene in the video. The children in the control group did not see any scene other than the model hitting the Bobo doll. In another group, the children observed the model getting rewarded for their actions. The last group saw the model getting punished and warned not to act aggressively toward the Bobo doll.

All three groups of children were then individually moved to a room with toys and a Bobo doll. Bandura observed that the children who saw the model receiving a punishment were less likely to be aggressive toward the doll.

A second observation was especially interesting. When researchers asked the children to act aggressively toward the Bobo doll, as they did in the movie, the children did.

This doesn’t sound significant, but it does make an interesting point about learned behaviors. The children learn the behavior by watching the model and observing their actions. Learning (aka remembering) the learning of the model’s actions occurred simply because the children were there to observe them.

Consequences simply influenced whether or not the children decided to perform the learned behaviors. The memory of the aggression was still present, whether or not the child saw that the aggression was rewarded or punished.

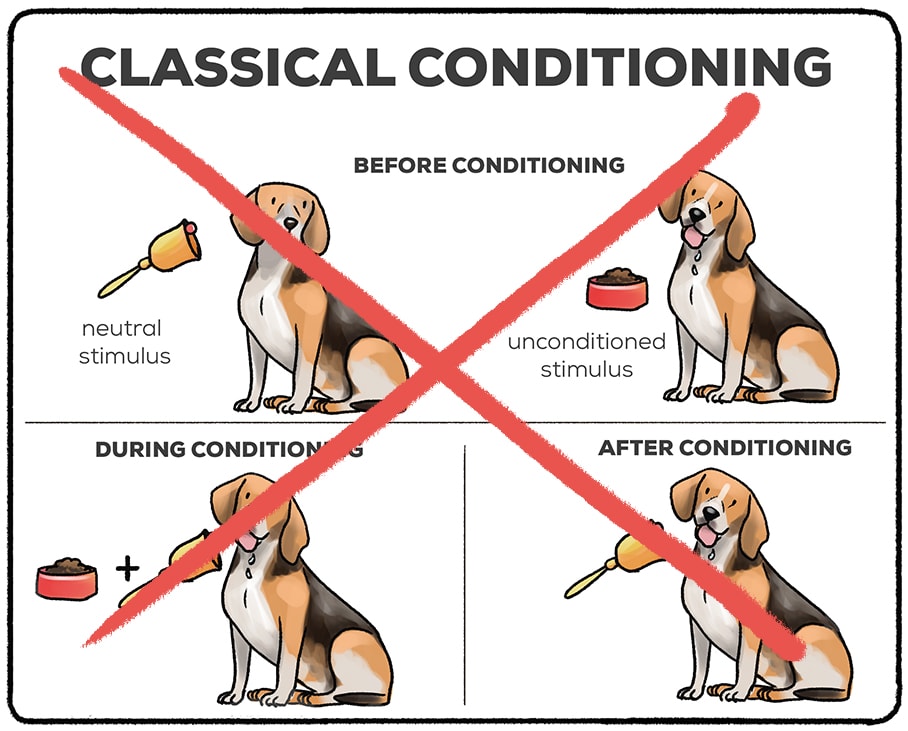

Is The Bobo Doll Experiment An Example of Operant Conditioning or Classical Conditioning?

Neither! Since operant and classical conditioning rely on explicit rewards or penalties to affect behavior repetition, they fall short of capturing the full scope of human learning. Conversely, observational learning is not dependent on these rewards. Albert Bandura's well-known "Bobo Doll" experiment is a striking example.

This experiment proved that without firsthand experience or outside rewards and penalties, people might learn only by watching others. The behaviorist ideas of the time, which were primarily dependent on reinforcement, faced a severe challenge from Bandura's research.

Criticism of the Bobo Doll Experiment

A Reddit user on the TodayILearned subreddit made a good point on how the Bobo Doll Experiment was conducted:

"A significant criticism of this study is that the Bobo doll is MEANT to be knocked around. It’s an inflatable toy with a weight at the bottom, it rocks back and forth and stands back up after it is hit.

How do we know that the kids didn’t watch the adults knock over the toy and say, 'That looks fun!' and then mimic them? These types of toys are still often sold as punching bag toys for kids. This study would have much more validity if they had used a different type of toy."

Bobo Doll Impact

There’s one more piece of the 1963 study that is worth mentioning. While some children in the experiment watched a movie, others watched a live model. Did this make a huge difference in whether or not the child learned and displayed aggressive behaviors?

Not really.

The Bobo Doll experiment has frequently been cited in discussions among psychologists and researchers, especially when debating the impact of violent media on children. A wealth of research has sought to determine whether children engage with violent video games and consume violent media, does it increase their likelihood to act out violently? Or, as suggested by the Bobo Doll experiment, do children merely internalize these behaviors and still maintain discretion over whether to act on them or not?

Multiple studies have aimed to tackle this question. For instance, research from the American Psychological Association has pointed to a link between violent video games and increased aggression, though not necessarily criminal violence. However, other sources, such as the Oxford Internet Institute , have found limited evidence to support a direct link between game violence and real-world violent actions. Despite the varying findings, the influence of Albert Bandura's introduction of observational learning and social learning theory cannot be understated. His Bobo Doll experiments remain pivotal in psychology's rich history.

Related posts:

- Albert Bandura (Biography + Experiments)

- 3 Theories of Aggression (Psychology Explained)

Observational Learning

- 40+ Famous Psychologists (Images + Biographies)

- Learning (Psychology)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Operant Conditioning

Classical Conditioning

Latent Learning

Experiential Learning

The Little Albert Study

Bobo Doll Experiment

Spacing Effect

Von Restorff Effect

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Child Abuse Prevention in a Pandemic-A Natural Experiment in Social Welfare Policy

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Pediatrics, Center for Safe and Healthy Families, Primary Children's Hospital, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

- 2 Division of General Pediatrics, Clinical Futures, and PolicyLab, Roberts Center for Pediatric Research, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- 3 Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Safar Center for Resuscitation Research, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- PMID: 37870864

- DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4525

PubMed Disclaimer

- Hospital Admissions for Abusive Head Trauma Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Maassel NL, Graetz E, Schneider EB, Asnes AG, Solomon DG, Leventhal JM. Maassel NL, et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Dec 1;177(12):1342-1347. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4519. JAMA Pediatr. 2023. PMID: 37870839

Similar articles

- How do Australian print media representations of child abuse and neglect inform the public and system reform?: stories place undue emphasis on social control measures and too little emphasis on social care responses. Lonne B, Gillespie K. Lonne B, et al. Child Abuse Negl. 2014 May;38(5):837-50. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.021. Child Abuse Negl. 2014. PMID: 24942127 No abstract available.

- Future challenges and opportunities in child welfare. Maluccio AN, Anderson GR. Maluccio AN, et al. Child Welfare. 2000 Jan-Feb;79(1):3-9. Child Welfare. 2000. PMID: 10659388 No abstract available.

- Village abuse: it takes a village. Fraad H. Fraad H. J Psychohist. 2012 Winter;39(3):203-11. J Psychohist. 2012. PMID: 22164724 No abstract available.

- The future of child and family welfare: selected readings. Maluccio AN. Maluccio AN. Child Welfare. 2000 Jan-Feb;79(1):115-24. Child Welfare. 2000. PMID: 10659395 Review.

- A Public Health Approach to Prevention: What Will It Take? Daro D. Daro D. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016 Oct;17(4):420-1. doi: 10.1177/1524838016658880. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016. PMID: 27580667 Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Silverchair Information Systems

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- About Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Risk and Protective Factors

- Program: Essentials for Childhood: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences through Data to Action

- Public Health Strategy

- Adverse childhood experiences can have long-term negative impacts on health, opportunity and well-being.

- Adverse childhood experiences are common and some groups experience them more than others.

What are adverse childhood experiences?

Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). Examples include: 1

- Experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect.

- Witnessing violence in the home or community.

- Having a family member attempt or die by suicide.

Also included are aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding. Examples can include growing up in a household with: 1

- Substance use problems.

- Mental health problems.

- Instability due to parental separation.

- Instability due to household members being in jail or prison.

The examples above are not a complete list of adverse experiences. Many other traumatic experiences could impact health and well-being. This can include not having enough food to eat, experiencing homelessness or unstable housing, or experiencing discrimination. 2 3 4 5 6

Quick facts and stats

ACEs are common. About 64% of adults in the United States reported they had experienced at least one type of ACE before age 18. Nearly one in six (17.3%) adults reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs. 7

Three in four high school students reported experiencing one or more ACEs, and one in five experienced four or more ACEs. ACEs that were most common among high school students were emotional abuse, physical abuse, and living in a household affected by poor mental health or substance abuse. 8

Preventing ACEs could potentially reduce many health conditions. Estimates show up to 1.9 million heart disease cases and 21 million depression cases potentially could have been avoided by preventing ACEs. 1 Preventing ACEs could reduce suicide attempts among high school students by as much as 89%, prescription pain medication misuse by as much as 84%, and persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness by as much as 66%. 8

Some people are at greater risk of experiencing one or more ACEs than others. While all children are at risk of ACEs, numerous studies show inequities in such experiences. These inequalities are linked to the historical, social, and economic environments in which some families live. 5 6 ACEs were highest among females, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native adults, and adults who are unemployed or unable to work. 7

ACEs are costly. ACEs-related health consequences cost an estimated economic burden of $748 billion annually in Bermuda, Canada, and the United States. 9

ACEs can have lasting effects on health and well-being in childhood and life opportunities well into adulthood. 10 Life opportunities include things like education and job potential. These experiences can increase the risks of injury, sexually transmitted infections, and involvement in sex trafficking. They can also increase risks for maternal and child health problems including teen pregnancy, pregnancy complications, and fetal death. Also included are a range of chronic diseases and leading causes of death, such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and suicide. 1 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

ACEs and associated social determinants of health, such as living in under-resourced or racially segregated neighborhoods, can cause toxic stress. Toxic stress, or extended or prolonged stress, from ACEs can negatively affect children’s brain development, immune system, and stress-response systems. These changes can affect children’s attention, decision-making, and learning. 19

Children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships. They may also have unstable work histories as adults and struggle with finances, job stability, and depression throughout life. 19 These effects can also be passed on to their own children. 20 21 22 Some children may face further exposure to toxic stress from historical and ongoing traumas. These historical and ongoing traumas include experiences of racial discrimination or the impacts of poverty resulting from limited educational and economic opportunities. 1 6

Adverse childhood experiences can be prevented. Certain factors may increase or decrease the risk of experiencing adverse childhood experiences.

Preventing adverse childhood experiences requires understanding and addressing the factors that put people at risk for or protect them from violence.

Creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments for all children prevent ACEs and help all children reach their full potential. These relationships and environments are essential to creating positive childhood experiences. We all have a role to play.

What CDC is doing

CDC is committed to building systems and communities that nurture development, and to ensuring that every child has the opportunity to thrive. By investing in the potential of all children and supporting their families and their communities, we can prevent ACEs before they happen, and buffer the risk of harm when they do happen.

CDC is dedicated to preventing, identifying, and responding to ACEs at the community, state, and national level so that all people can achieve lifelong health and wellbeing. Our goal is to create the conditions for strong, thriving families and communities where children and youth are free from harm.

CDC's four strategic goals for ACEs prevention and response include:

- Support ACEs surveillance and data innovation.

- Expand what we know about evidence-based ACEs prevention and positive childhood experiences promotion.

- Build local, state, tribal, and key partner capacity.

- Increase awareness and understanding among key partners.

CDC's ACEs Prevention Strategy expands upon these goals and outlines specific objectives for ACEs prevention and response.

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention — 25 States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:999-1005. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1 .

- Cain KS, Meyer SC, Cummer E, Patel KK, Casacchia NJ, Montez K, Palakshappa D, Brown CL. Association of Food Insecurity with Mental Health Outcomes in Parents and Children. Science Direct. 2022; 22:7; 1105-1114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2022.04.010 .

- Smith-Grant J, Kilmer G, Brener N, Robin L, Underwood M. Risk Behaviors and Experiences Among Youth Experiencing Homelessness—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 23 U.S. States and 11 Local School Districts. Journal of Community Health. 2022; 47: 324-333.

- Experiencing discrimination: Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health | Annual Review of Public Health https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940 .

- Sedlak A, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4): Report to Congress. Executive Summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health an Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.; 2010.

- Font S, Maguire-Jack K. Pathways from childhood abuse and other adversities to adult health risks: The role of adult socioeconomic conditions. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:390-399.

- Swedo EA, Aslam MV, Dahlberg LL, et al. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among U.S. Adults — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:707–715. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7226a2 .

- Swedo EA, Pampati S, Anderson KN, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Conditions and Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2023. MMWR Suppl 2024;73(Suppl-4):39–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7304a5 .

- Bellis, MA, et al. Life Course Health Consequences and Associated Annual Costs of Adverse Childhood Experiences Across Europe and North America: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019.

- Adverse Childhood Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Associations with Poor Mental Health and Suicidal Behaviors Among High School Students — Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021 | MMWR

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004 Feb;113(2):320-7.

- Miller ES, Fleming O, Ekpe EE, Grobman WA, Heard-Garris N. Association Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology . 2021;138(5):770-776. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004570 .

- Sulaiman S, Premji SS, Tavangar F, et al. Total Adverse Childhood Experiences and Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review. Matern Child Health J . 2021;25(10):1581-1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03176-6 .

- Ciciolla L, Shreffler KM, Tiemeyer S. Maternal Childhood Adversity as a Risk for Perinatal Complications and NICU Hospitalization. Journal of Pediatric Psychology . 2021;46(7):801-813. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab027 .

- Mersky JP, Lee CP. Adverse childhood experiences and poor birth outcomes in a diverse, low-income sample. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2560-8 .

- Reid JA, Baglivio MT, Piquero AR, Greenwald MA, Epps N. No youth left behind to human trafficking: Exploring profiles of risk. American journal of orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(6):704.

- Diamond-Welch B, Kosloski AE. Adverse childhood experiences and propensity to participate in the commercialized sex market. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 Jun 1;104:104468.

- Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, & Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

- Narayan AJ, Kalstabakken AW, Labella MH, Nerenberg LS, Monn AR, Masten AS. Intergenerational continuity of adverse childhood experiences in homeless families: unpacking exposure to maltreatment versus family dysfunction. Am J Orthopsych. 2017;87(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000133 .

- Schofield TJ, Donnellan MB, Merrick MT, Ports KA, Klevens J, Leeb R. Intergenerational continuity in adverse childhood experiences and rural community environments. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(9):1148-1152. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304598 .

- Schofield TJ, Lee RD, Merrick MT. Safe, stable, nurturing relationships as a moderator of intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(4 Suppl):S32-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.004 .

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

ACEs can have a tremendous impact on lifelong health and opportunity. CDC works to understand ACEs and prevent them.

For Everyone

Public health.

- Policy Tools & Publications

- Child Abuse Prevention in a Pandemic—A…

Child Abuse Prevention in a Pandemic—A Natural Experiment in Social Welfare Policy

Maassel and colleagues examine trends in abusive head trauma in the 2 years following the first COVID-19–related shutdowns. Relying on a database of admissions for AHT at 49 children’s hospitals across the US from January 2016 through April 2022, the authors report that COVID-19–related shutdowns in the spring of 2020 were associated with a 25% reduction in the incidence of hospitalizations for AHT among children younger than 5 years. Analysis of trends following the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, uncovers a steady rise in AHT incidence back toward prepandemic levels among infants, who account for 75% of all AHT cases. If replicated by future research, these results suggest that pandemic-related policies served as an unplanned child abuse prevention program with a rate of success far above that described for any established child abuse prevention efforts.

Campbell KA, Wood JN, Berger RP

Adolescent Health & Well-Being

Behavioral health, population health sciences, health equity, family & community health.

The lasting impact of neglect

Psychologists are studying how early deprivation harms children — and how best to help those who have suffered from neglect.

By Kirsten Weir

June 2014, Vol 45, No. 6

Print version: page 36

10 min read

- Mental Health

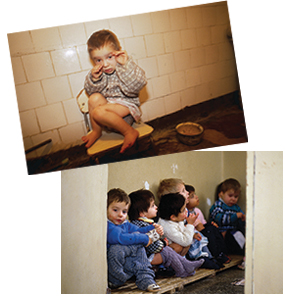

The babies laid in cribs all day, except when being fed, diapered or bathed on a set schedule. They weren't rocked or sung to. Many stared at their own hands, trying to derive whatever stimulation they could from the world around them. "Basically these kids were left on their own," Fox says.

Fox, along with colleagues Charles Nelson, PhD, at Harvard Medical School and Children's Hospital Boston, and Charles Zeanah, MD, at Tulane University, have followed those children for 14 years. They describe their Bucharest Early Intervention Project in a new book, "Romania's Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and the Struggle for Recovery" (2014).

Neglect isn't just a Romanian problem, of course. UNICEF estimates that as many as 8 million children are growing up in institutional settings around the world. In the United States, neglect is a less obvious — though very real — concern. According to a report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 676,569 U.S. children were reported to have experienced maltreatment in 2011. Of those, more than 78 percent suffered from neglect.

The list of problems that stem from neglect reads like the index of the DSM: poor impulse control, social withdrawal, problems with coping and regulating emotions, low self-esteem, pathological behaviors such as tics, tantrums, stealing and self-punishment, poor intellectual functioning and low academic achievement. Those are just some of the problems that David A. Wolfe, PhD, a psychologist at the University of Toronto, and his former student Kathryn L. Hildyard, PhD, detailed in a 2002 review ( Child Abuse & Neglect , 2002).

"Across the board, these are kids who have severe problems throughout their lifetime," says Wolfe, recent past editor-in-chief of Child Abuse & Neglect .

Now, researchers are beginning to understand some of the ways that early deprivation alters a person's brain and behavior — and whether that damage can be undone.

The Bucharest project

In 1989 Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu was overthrown, and the world discovered that 170,000 children were being raised in Romania's impoverished institutions. As the children's plight became public, Fox, Nelson and Zeanah realized they had a unique opportunity to study the effects of early institutionalization.

The trio launched their project in 2000 and began by assessing 136 children who had been living in Bucharest's institutions from birth. Then they randomly assigned half of the children to move into Romanian foster families, whom the researchers recruited and assisted financially. The other half remained in care as usual. The children ranged in age from 6 months to nearly 3 years, with an average age of 22 months.

Over the subsequent months and years, the researchers returned to assess the development of the children in both settings. They also evaluated a control group of local children who had never lived in an institution.

They found many profound problems among the children who had been born into neglect. Institutionalized children had delays in cognitive function, motor development and language. They showed deficits in socio-emotional behaviors and experienced more psychiatric disorders. They also showed changes in the patterns of electrical activity in their brains, as measured by EEG.

For kids who were moved into foster care, the picture was brighter. These children showed improvements in language, IQ and social-emotional functioning. They were able to form secure attachment relationships with their caregivers and made dramatic gains in their ability to express emotions.

While foster care produced notable improvements, though, children in foster homes still lagged behind the control group of children who had never been institutionalized. And some foster children fared much better than others. Those removed from the institutions before age 2 made the biggest gains. "There's a bit of plasticity in the system," Fox says. But to reverse the effects of neglect, he adds, "the earlier, the better."

In fact, when kids were moved into foster care before their second birthdays, by age 8 their brains' electrical activity looked no different from that of community controls. The researchers also used structural MRI to further understand the brain differences among the children. They found that institutionalized children had smaller brains, with a lower volume of both gray matter (which is made primarily of the cell bodies of neurons) and white matter (which is mainly the nerve fibers that transmit signals between neurons).

"A history of institutionalization significantly affected brain growth," Fox says.

The institutionalized children who were moved into foster homes recovered some of that missing white matter volume over time. Their gray matter volume, however, stayed low, whether or not they had been moved into stable homes ( PNAS , 2012). Those brain changes, the researchers found, were associated with an increased risk of ADHD symptoms.

Many of the children remain with their foster families. (The researchers no longer support those families financially, but the Romanian government continues to provide stipends for the children's care.) Soon, Fox says, he and his colleagues will begin the 16-year assessment. They expect that to be particularly telling, since the effects of adversity in early childhood can re-emerge during adolescence.

Regardless of future findings, Fox has seen enough evidence to draw hard conclusions. "Children need to be in socially responsive situations. I personally think that there aren't good institutions for young children," he says. With millions of children growing up in similar conditions, he adds, "this is a worldwide public health issue."

Coming to America

In the United States, Megan Gunnar, PhD, director of the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota, has helped fill in other pieces of the puzzle. In 1999, she and her colleagues launched the International Adoption Project, an extensive examination of children adopted from overseas. She now has nearly 6,000 names on her registry and her research is ongoing.

Gunnar has found certain brain changes are common among children who came to the United States from orphanages, including a reduction in brain volume and changes in the development of the prefrontal cortex.

"Neglect does a number on the brain. And we see behaviors that follow from that," she says.

She's found post-institutionalized kids tend to have difficulty with executive functions such as cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control and working memory. They are often delayed in the development of theory of mind, the ability to understand the mental states of others. Many struggle to regulate their emotions. Often, they suffer from high anxiety.

One of the most common behaviors she sees among post-institutionalized children is indiscriminate friendliness. "A child who doesn't know you from Adam will run up, put his arms around you and snuggle in like you're his long-lost aunt," Gunnar says. That friendliness was probably an important coping technique in their socially starved early lives, she says. "What's interesting is it just doesn't go away."

Fox and his colleagues had also noted such disarming friendliness in the Romanian orphanages. Initially, children with indiscriminate friendliness were thought to have an attachment disorder that prevented them from forming healthy connections with adult caregivers. But findings from the Bucharest Project as well as Gunnar's own research have demonstrated otherwise, she says.

In a study of 65 toddlers who had been adopted from institutions, Gunnar found that most attached to their new parents relatively quickly, and by nine months post-adoption, 90 percent of the children had formed strong attachments to their adoptive parents. Yet that attachment was often "disorganized," marked by contradictory behaviors ( Development and Psychopathology , in press). A child might appear confused in the presence of a caregiver, for instance, sometimes approaching the caregiver for comfort, and other times showing resistance.

"There were things that happened in terms of early development, when they lacked that responsive caregiver, that they're carrying forward," Gunnar says.

One of those things may be a disrupted cortisol pattern. Cortisol, commonly known as the "stress hormone," typically peaks shortly after waking, then drops throughout the day to a low point at bedtime. But Gunnar found that children with a history of neglect typically have a less marked cortisol rhythm over the course of the day. Those abnormal cortisol patterns were correlated with both stunted physical growth and with indiscriminate friendliness ( Development and Psychopathology , 2011).

Indiscriminate friendliness may also be tied to the amygdala. In a study using fMRI, Aviva Olsavsky, MD, at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues found that when typical children viewed photos of their mothers versus photos of strangers, the amygdala showed distinctly different responses. In children who had been institutionalized, however, the amygdala responded similarly whether the children viewed mothers or strangers. That response was particularly notable among kids who exhibited more friendliness toward strangers ( Biological Psychiatry , 2013).

Closer to home

Other researchers are also exploring physiological differences in children who have experienced neglect. Around the time Gunnar was launching her adoption study, Philip Fisher, PhD, a psychologist and research scientist at the University of Oregon, was working with American foster children. Initially, he suspected the behavioral and developmental difficulties they experienced stemmed from physical abuse. But as he shared data with Gunnar and others, he realized they looked a lot like post-institutionalized children.

Though cortisol tends to follow a daily cycle, it also spikes during times of stress. Fisher expected that his foster children, who had clearly experienced stressful situations, might show high levels, too. Instead, he discovered something quite different. "Their levels were low in the morning and stayed low throughout the day," he says.

Combing through the case records of the children in his sample, he discovered that disregulated cortisol was not associated with physical or sexual abuse, but with early neglect. "This blunted daily pattern with low morning cortisol seemed to be a hallmark of neglect," he says. "That was a pretty powerful picture."

In fact, abnormal cortisol cycles have previously been noted in a variety of psychological disorders, Fisher says, including anxiety, mood disorders, behavior problems and post-traumatic stress disorder. But the good news: Cortisol patterns appear to be changeable.

Fisher found that foster kids living with more responsive caregivers were more likely to develop more normal cortisol patterns over time. Kids living with caregivers who were stressed out themselves didn't show that recovery ( Psychoneuroendocrinology , 2007). "We're more likely to see that blunted pattern when they don't get that support, and there's a lot of stress in the family," he says.

Helping caregivers manage their own stress and develop more positive interactions with their children may help reset the kids' stress responses. Fisher is now developing and testing video coaching programs that aim to identify and reinforce the positive interactions foster parents are already having with their young children. "We can show people very precisely the things we know are at the core of promoting healthy development," he says.

Meanwhile, he's also looking for other physiological systems affected by early adverse experience — particularly those that are malleable. "If we can impact those systems, especially without pharmacology, we have great tools we can leverage," he says.

For instance, kids with a history of neglect are known to have trouble with executive functioning. One way that presents itself is that the kids don't show much brain response to corrective feedback; instead, they often make the same mistakes over and over. Targeted interventions may help those children learn to tune in to the important cues they're missing, Fisher says. Though more research is needed, he adds, computer-based brain-training games and other novel interventions might prove to be useful complements to more traditional therapy.

Despite progress, child neglect remains underfunded and understudied, says Wolfe. Politically, it's a prickly subject. "Neglect is not a disease. It's entwined with the delivery of proper social and medical services. It's embedded in socioeconomic disadvantage," he says.

Politics aside, science is making strides toward erasing the stamp that early neglect leaves on a child. New understanding of the ways that neglect changes a person's physiology is helping to push the field forward, Wolfe says.

That progress is sorely needed, but the most important first step is to remove neglected children to a safe, loving environment, he adds. "The brain will often recover, if it's allowed to."

Kirsten Weir is a journalist in Minneapolis.

Further reading

- Bruce, J., Gunnar, M. R., Pears, K. C., and Fisher, P. A. (2013). Early adverse care, stress neurobiology, and prevention science: Lessons learned. Prevention Science, 14 (3), 247–256.

- Nelson, C. A., Fox, N. A., and Zeanah, C. H. (2014). Romania's abandoned children: Deprivation, brain development, and the struggle for recovery . Cambridge, MA, and London, England: Harvard University Press.

- Nelson III, C. A., Zeanah, C. H., Fox, N. A., Marshall, P. J., Smyke, A. T., and Guthrie, D. (2007). Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science, 318 (5858), 1937–2940.

Digital Edition

- Video: Izidor Ruckel is a Romanian orphan who has made it his life’s work to help other orphans .

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

Find anything you save across the site in your account

As a college student, B. F. Skinner gave little thought to psychology. He had hoped to become a novelist, and majored in English. Then, in 1927, when he was twenty-three, he read an essay by H. G. Wells about the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. The piece, which appeared in the Times Magazine , was ostensibly a review of the English translation of Pavlov’s “Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex.” But, as Wells pointed out, it was “not an easy book to read,” and he didn’t spend much time on it. Instead, Wells described Pavlov, whose systematic approach to physiology had revolutionized the study of medicine, as “a star which lights the world, shining down a vista hitherto unexplored.”

That unexplored world was the mechanics of the human brain. Pavlov had noticed, in his research on the digestive system of dogs, that they drooled as soon as they saw the white lab coats of the people who fed them. They didn’t need to see, let alone taste, the food in order to react physically. Dogs naturally drooled when fed: that was, in Pavlov’s terms, an “unconditional” reflex. When they drooled in response to a sight or sound that was associated with food by mere happenstance, a “conditional reflex” (to a “conditional stimulus”) had been created. Pavlov had formulated a basic psychological principle—one that also applied to human beings—and discovered an objective way to measure how it worked.

Skinner was enthralled. Two years after reading the Times Magazine piece, he attended a lecture that Pavlov delivered at Harvard and obtained a signed picture, which adorned his office wall for the rest of his life. Skinner and other behaviorists often spoke of their debt to Pavlov, particularly to his view that free will was an illusion, and that the study of human behavior could be reduced to the analysis of observable, quantifiable events and actions.

But Pavlov never held such views, according to “Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science” (Oxford), an exhaustive new biography by Daniel P. Todes, a professor of the history of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. In fact, much of what we thought we knew about Pavlov has been based on bad translations and basic misconceptions. That begins with the popular image of a dog slavering at the ringing of a bell. Pavlov “never trained a dog to salivate to the sound of a bell,” Todes writes. “Indeed, the iconic bell would have proven totally useless to his real goal, which required precise control over the quality and duration of stimuli (he most frequently employed a metronome, a harmonium, a buzzer, and electric shock).”

Pavlov is perhaps best known for introducing the idea of the conditioned reflex, although Todes notes that he never used that term. It was a bad translation of the Russian uslovnyi , or “conditional,” reflex. For Pavlov, the emphasis fell on the contingent, provisional nature of the association—which enlisted other reflexes he believed to be natural and unvarying. Drawing upon the brain science of the day, Pavlov understood conditional reflexes to involve a connection between a point in the brain’s subcortex, which supported instincts, and a point in its cortex, where associations were built. Such conjectures about brain circuitry were anathema to the behaviorists, who were inclined to view the mind as a black box. Nothing mattered, in their view, that could not be observed and measured. Pavlov never subscribed to that theory, or shared their disregard for subjective experience. He considered human psychology to be “one of the last secrets of life,” and hoped that rigorous scientific inquiry could illuminate “the mechanism and vital meaning of that which most occupied Man—our consciousness and its torments.” Of course, the inquiry had to start somewhere. Pavlov believed that it started with data, and he found that data in the saliva of dogs.

Pavlov’s research originally had little to do with psychology; it focussed on the ways in which eating excited salivary, gastric, and pancreatic secretions. To do that, he developed a system of “sham” feeding. Pavlov would remove a dog’s esophagus and create an opening, a fistula, in the animal’s throat, so that, no matter how much the dog ate, the food would fall out and never make it to the stomach. By creating additional fistulas along the digestive system and collecting the various secretions, he could measure their quantity and chemical properties in great detail. That research won him the 1904 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But a dog’s drool turned out to be even more meaningful than he had first imagined: it pointed to a new way to study the mind, learning, and human behavior.

“Essentially, only one thing in life is of real interest to us—our psychical experience,” he said in his Nobel address. “Its mechanism, however, was and still is shrouded in profound obscurity. All human resources—art, religion, literature, philosophy, and the historical sciences—all have joined in the attempt to throw light upon this darkness. But humanity has at its disposal yet another powerful resource—natural science with its strict objective methods.”

Pavlov had become a spokesman for the scientific method, but he was not averse to generalizing from his results. “That which I see in dogs,” he told a journalist, “I immediately transfer to myself, since, you know, the basics are identical.”

Ivan Pavlov was born in 1849 in the provincial Russian city of Ryazan, the first of ten children. As the son of a priest, he attended church schools and the theological seminary. But he struggled with religion from an early age and, in 1869, left the seminary to study physiology and chemistry at St. Petersburg University. His father was furious, but Pavlov was undeterred. He never felt comfortable with his parents—or, as this biography makes clear, with almost anyone else. Not long after “The Brothers Karamazov” was published, Pavlov confessed to his future wife, Seraphima Vasilievna Karchevskaya, who was a friend of Dostoyevsky’s, that he identified with the rationalist Ivan Karamazov, whose brutal skepticism condemned him, as Todes notes, to nihilism and breakdown. “The more I read, the more uneasy my heart became,” Pavlov wrote in a letter to Karchevskaya. “Say what you will, but he bears a great resemblance to your tender and loving admirer.”

Pavlov entered the intellectual world of St. Petersburg at an ideal moment for a man eager to explore the rules that govern the material world. The tsar had freed the serfs in 1861, helping to push Russia into the convulsive century that followed. Darwin’s theory of evolution was starting to reverberate across Europe. Science began to matter in Russia in a way it hadn’t before. At the university, Pavlov’s freshman class in inorganic chemistry was taught by Dmitri Mendeleev, who, a year earlier, had created the periodic table of the elements as a teaching tool. The Soviets would soon assign religion to the dustbin of history, but Pavlov got there ahead of them. For him, there was no religion except the truth. “It is for me a kind of God, before whom I reveal everything, before whom I discard wretched worldly vanity,” he wrote. “I always think to base my virtue, my pride, upon the attempt, the wish for truth , even if I cannot attain it.” One day, while walking to his lab at the Institute for Experimental Medicine, Pavlov watched with amazement as a medical student stopped in front of a church and crossed himself. “Think about it!” Pavlov told his colleagues. “A naturalist, a physician, but he prays like an old woman in an almshouse!”

Pavlov was not a pleasant person. Todes presents him as a volatile child, a difficult student, and, frequently, a nasty adult. For decades, his lab staff knew to stay away, if at all possible, on his “angry days,” and there were many. As a member of the liberal intelligentsia, he was opposed to restrictive measures aimed at Jews, but in his personal life he freely voiced anti-Semitic sentiments. Pavlov once referred to “that vile yid, Trotsky,” and, when complaining about the Bolsheviks in 1928, he told W. Horsley Gantt, an American scientist who spent years in his lab, that Jews occupied “high positions everywhere,” and that it was “a shame that the Russians cannot be rulers of their own land.”

In lectures, Pavlov insisted that medicine had to be grounded in science, on data that could be explained, verified, and analyzed, and on studies that could be repeated. Drumming up support among physicians for the scientific method may seem banal today, but at the end of the nineteenth century it wasn’t an easy sell. In Russia, and even to some degree in the West, physiology was still considered a “theoretical science,” and the connection between basic research and medical treatments seemed tenuous. Todes argues that Pavlov’s devotion to repeated experimentation was bolstered by the model of the factory, which had special significance in a belatedly industrializing Russia. Pavlov’s lab was essentially a physiology factory, and the dogs were his machines.

To study them, he introduced a rigorous experimental approach that helped transform medical research. He recognized that meaningful changes in physiology could be assessed only over time. Rather than experiment on an animal once and then kill it, as was common, Pavlov needed to keep his dogs alive. He referred to these studies as “chronic experiments.” They typically involved surgery. “During chronic experiments, when the animal, having recovered from its operation, is under lengthy observation, the dog is irreplaceable,” he noted in 1893.

Link copied

The dogs may have been irreplaceable, but their treatment would undoubtedly cause an outcry today. Todes writes that in early experiments Pavlov was constantly stymied by the difficulty of keeping his subjects alive after operating on them. One particularly productive dog had evidently set a record by producing active pancreatic juice for ten days before dying. The loss was a tremendous disappointment to Pavlov. “Our passionate desire to extend experimental trials on such a rare animal was foiled by its death as a result of extended starvation and a series of wounds,” Pavlov wrote at the time. As a result, “the expected resolution of many important and controversial questions” had been delayed, awaiting another champion test subject.

If Pavlov’s notes were voluminous, Todes’s own investigations are hardly modest. He spent years researching this biography and has made excellent use of archives in Russia, Europe, and the United States. No scholar of Pavlov or of the disciplines he inspired will be able to ignore this achievement. The book’s eight hundred and fifty-five pages are filled with a vast accumulation of data, although the reader might have been better served if Todes had left some of it out. No minutia appears to have been too obscure to include. Here is Todes describing data that Pavlov had assembled from one extended experiment: “The total amount of secretion in trials 6 and 8 is too low, and the slope of these curves diverges markedly at several points from that in trial 1. Trial 9 fits trial 1 more snugly than does trial 5 in terms of total secretion, but the amount of secretion more than doubles in the second hour, contrasting sharply with the slight decline in trial 1. Trial 10 is again a good fit in terms of total amount of secretion, but the amount of secretion rises inappropriately in the fourth hour.” The diligent reader can also learn, in excruciating detail, what time Pavlov took each meal during summer holidays (dinner at precisely 12:30 P . M ., tea at four, and supper at eight), how many cups of tea he typically consumed each afternoon (between six and ten), and where the roses were planted in his garden (“around the spruce tree on the west side of the veranda”). It’s hard not to wish that Todes had been a bit less devoted to his subject’s prodigious empiricism.

For more than thirty years, Pavlov’s physiology factory turned out papers, new research techniques, and, of course, gastric juice—a lot of it. On a good day, a hungry dog could produce a thousand cubic centimetres, more than a quart. Although this was a sideline for Pavlov, the gastric fluids of a dog became a popular treatment for dyspepsia, and not just in Russia. A “gastric juice factory” was set up for the purpose. “An assistant was hired and paid thirty rubles a month to oversee the facility,” Todes writes. “Five large young dogs, weighing sixty to seventy pounds and selected for their voracious appetites, stood on a long table harnessed to the wooden crossbeam directly above their heads. Each was equipped with an esophagotomy and fistula from which a tube led to the collection vessel. Each ‘factory dog’ faced a short wooden stand tilted to display a large bowl of minced meat.” By 1904, the venture was selling more than three thousand flagons of gastric juice annually, Todes writes, and the profits helped increase the lab budget by about seventy per cent. The money was helpful. So was the apparent demonstration that a product created in an experimental laboratory could become useful to doctors all over the world.

At the turn of the century, Pavlov had begun focussing his research on “psychic secretions”: drool produced by anything other than direct exposure to food. He spent most of the next three decades exploring the ways conditional reflexes could be created, refined, and extinguished. Before feeding a dog, Pavlov might set a metronome at, say, sixty beats a minute. The next time the dog heard a metronome at any speed, it would salivate. But when only that particular metronome setting was reinforced with food the dog became more discriminating. Pavlov deduced that there were colliding forces of “excitation” and “inhibition” at play—so that, at first, the stimulus spreads across the cerebral cortex and then, in the second phase, it concentrates at one specific spot.

As his formulations and models grew more complex, Pavlov was encouraged in his hope that he would be able to approach psychology through physiology. “It would be stupid to reject the subjective world,” he remarked later. “Our actions, all forms of social and personal life are formed on this basis. . . . The question is how to analyze this subjective world.”

Pavlov was sixty-eight and had been famous for years when Lenin came to power, and Todes is at his best in describing the scientist’s relationship with the regime that he would serve for the rest of his life. Pavlov harbored no sentimental attachment to the old order, which had never been aggressive in funding scientific research. The Bolsheviks promised to do better (and, eventually, they did). Yet Pavlov considered Communism a “doomed” experiment that had turned Russia back into a nation of serfs. “Of course, in the struggle between labor and capital the government must stand for the protection of the worker,” he said in a speech. “But what have we made of this? . . . That which constitutes the culture, the intellectual strength of the nation, has been devalued, and that which for now remains a crude force, replaceable by a machine, has been moved to the forefront. All this, of course, is doomed to destruction as a blind rejection of reality.”

Lenin had too many other problems to spend his time worrying about one angry scientist. At first, Pavlov, his wife, and their four children were treated like any other Soviet citizens. Their Nobel Prize money was confiscated as property of the state. From 1917 to 1920, like most residents of Petrograd, which would soon be called Leningrad, the Pavlovs struggled to feed themselves and to keep from freezing. It was nearly a full-time occupation; at least a third of Pavlov’s colleagues at the Russian Academy of Sciences died in those first post-revolutionary years. “Some starved to death in apartments just above or below his own in the Academy’s residence,” Todes writes. Pavlov grew potatoes and other vegetables right outside his lab, and when he was sick a colleague provided small amounts of firewood to burn at home.

In 1920, Pavlov wrote to Lenin’s secretary, Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, seeking permission to emigrate, although, as Todes points out, it was probably not yet necessary to ask. Pavlov wanted to see if, as he suspected, universities in Europe or America would fund his research in circumstances that would prevent his dogs and lab workers from starving. Bonch-Bruevich turned the letter over to Lenin, who immediately grasped the public-relations repercussions of losing the country’s most celebrated scientist. He instructed Petrograd Party leaders to increase rations for Pavlov and his family, and to make sure his working conditions improved.

The Soviets came to regard Pavlov as a scientific version of Marx. The comparison could not entirely have pleased Pavlov, who rebelled at the “divine” authority accorded Marx (“that fool”) and denied that his own “approach represents pure materialism.” Indeed, where others thought that the notion of free will would come to be discarded once we had a full understanding of how the mind worked, Pavlov was, at least at times, inclined to think the opposite. “We would have freedom of the will in proportion to our knowledge of the brain,” he told Gantt in 1927, just as “we had passed from a position of slave to a lord of nature.”

That year, Stalin began a purge of intellectuals. Pavlov was outraged. At a time when looking at the wrong person in the wrong way was enough to send a man to the gulag, he wrote to Stalin saying that he was “ashamed to be called a Russian.” Nikolai Bukharin, who considered Pavlov indispensable, made the case for him: “I know that he does not sing the ‘Internationale,’ ” Bukharin wrote to Valerian Kuibyshev, the head of the state planning committee. “But . . . despite all his grumbling, ideologically (in his works, not in his speeches) he is working for us.”

Stalin agreed. Pavlov prospered even at the height of the Terror. By 1935-36, he was running three separate laboratories and overseeing the work of hundreds of scientists and technicians. He was permitted to collaborate with scholars in Europe and America. Still, his relationship with the government was never easy. Soviet leaders even engaged in a debate over whether to celebrate his eightieth birthday. “A new nonsensical letter from academician Pavlov,” Molotov wrote in the margin of a letter of complaint before it was passed to Stalin. Kuibyshev was deeply opposed to any state recognition. “Pavlov spits on the Soviets, declares himself an open enemy, yet Soviet power would for some reason honor him,” he grumbled. “Help him we must,” he said at the time, “but not honor him.” For a while, Kuibyshev prevailed, but in 1936, when Pavlov died, at eighty-six, a hundred thousand mourners, including Party officials, filed past his casket as he lay in state.

What Todes describes as Pavlov’s “grand quest”—to rely on saliva drops and carefully calibrated experiments to understand the mechanics of human psychology—lives on, in various forms. Classical conditioning remains a critical tool: it is widely used to treat psychiatric disorders, particularly phobias. But the greater pursuit is for a kind of unified field theory in which psychology and physiology—the subjective and the material realms—would finally be integrated.

And so we have entered the age of the brain. The United States and other countries have embarked upon brain-mapping initiatives, and Pavlov would have endorsed their principal goal: to create a dynamic picture of the brain that demonstrates, at the cellular level, how neural circuits interact. As Todes points out, while Pavlov examined saliva in his attempts to understand human psychology, today we use fMRIs in our heightened search for the function of every neuron. When he delivered his lectures on the “larger hemispheres of the brain,” Pavlov declared, “We will hope and patiently await the time when a precise and complete knowledge of our highest organ, the brain, will become our profound achievement and the main foundation of a durable human happiness.” We are still waiting, but less patiently than before. ♦

- DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4525

- Corpus ID: 264425698

Child Abuse Prevention in a Pandemic-A Natural Experiment in Social Welfare Policy.

- Kristine A. Campbell , Joanne N. Wood , Rachel P. Berger

- Published in JAMA pediatrics 23 October 2023

- Political Science

18 References