Newsletter Sign Up

Email Address

Your browser is outdated, it may not render this page properly, please upgrade .

Bhasin v. Union of India

Closed Mixed Outcome

- Key details

Key Details

- Mode of Expression Electronic / Internet-based Communication

- Date of Decision January 10, 2020

- Outcome Declaratory Relief

- Case Number Writ Petition (Civil) No. 1031/2019

- Region & Country India, Asia and Asia Pacific

- Judicial Body Supreme (court of final appeal)

- Type of Law Criminal Law

- Themes Access to Public Information, Internet Shutdowns, National Security

- Tags Public Order

Content Attribution Policy

Global Freedom of Expression is an academic initiative and therefore, we encourage you to share and republish excerpts of our content so long as they are not used for commercial purposes and you respect the following policy:

- Attribute Columbia Global Freedom of Expression as the source.

- Link to the original URL of the specific case analysis, publication, update, blog or landing page of the down loadable content you are referencing.

Attribution, copyright, and license information for media used by Global Freedom of Expression is available on our Credits page.

This case is available in additional languages: View in: Français View in: العربية

Case Analysis

Case summary and outcome.

The Supreme Court of India ruled that an indefinite suspension of internet services would be illegal under Indian law and that orders for internet shutdown must satisfy the tests of necessity and proportionality. The case concerned the internet and movement restrictions imposed in the Jammu and Kashmir region in India on August 4, 2019, in the name of protecting public order. In the end, however, the Court did not lift the internet restrictions and instead, it directed the government to review the shutdown orders against the tests outlined in its judgment and lift those that were not necessary or did not have a temporal limit. The Court reiterated that freedom of expression online enjoyed Constitutional protection, but could be restricted in the name of national security. The Court held that though the Government was empowered to impose a complete internet shutdown, any order(s) imposing such restrictions had to be made public and was subject to judicial review.

Jammu and Kashmir is an Indian territory bordering Pakistan that has been the subject of a decades-long dispute between the two countries. Under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, the territory enjoyed special status, had its own Constitution and Indian citizens from other states were not allowed to purchase land or property there. On August 5, 2019, the Indian Government issued Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019 , which stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status that it had enjoyed since 1954 and made it fully subservient to all provisions of the Constitution of India.

In the days leading up to this Constitutional Order, the Indian government began imposing restrictions on online communication and freedom of movement. On August 2, the Civil Secretariat, Home Department, Government of Jammu and Kashmir, advised tourists and Amarnath Yatra pilgrims to leave the Jammu and Kashmir area in India. Subsequently, schools and offices were ordered to remain closed until further notice. On August 4, 2019, mobile phone networks, internet services, landline connectivity were all shutdown in the region. The District Magistrates imposed additional restrictions on freedoms of movement and public assembly citing authority to do so under Section 144 of the Criminal Penal Code.

The internet shutdown and movement restrictions (hereafter “restrictions”) limited the ability of journalists to travel and to publish and accordingly were challenged in court for their violations of Article 19 of India’s Constitution which guarantees the right to freedom of expression. In this context, the Supreme Court of India reviewed the following petitions challenging the legality of the internet shutdown and movement restrictions:

- the petition was brought by Ms. Anuradha Bhasin, the editor of the Kashmir Times Srinagar Edition. She argued the internet is essential for the modern press and that by shutting it down, the authorities forced the print media to come to “a grinding halt.” Because of this she had been unable to publish her newspaper since August 6, 2019. She also argued that the government failed to consider whether the internet shutdown was reasonable and proportionate to the aims it pursued. She argued that the restrictions were passed in the belief that there would be “a danger to law and order. However, public order is not the same as law and order and neither were at risk when the order was passed.”

- an Intervenor in the matter argued that by giving the State carte blanche to restrict fundamental rights in the name of national security and terrorism prevention would allow the State to impose broad restrictions on fundamental rights in varied situations. Further, the restrictions censored the discussion of the passage of the Constitutional Amendment stripping Jammu and Kashmir of special status by the persons living there. Lastly, the restrictions were supposedly temporary in nature, but lasted over 100 days.

- another Intervenor in this matter argued that the State failed to prove the necessity of the restrictions. “The people have a right to speak their view, whether good, bad or ugly, and the State must prove that it was necessary to restrict the same.” Further, the petitioner argued that the restriction was not proportionate. The State had to consider the effect of the restrictions on fundamental rights, which did not occur here. “it is not just the legal and physical restrictions that must be looked at, but also the fear that these sorts of restrictions engender in the minds of the populace, while looking at the proportionality of measures.”

- the petitioner Mr. Ghulam Nabi Azad (a Member of Parliament belonging to the largest opposition party in India’s upper house) argued that restrictions must be based on objective reasons and not merely on conjectures. Moreover, the official orders must not be kept secret by the State. The state of emergency used by the authorities to justify the restrictions could be declared only in light of an “internal disturbance” or “external aggression” under Article 356 of the Constitution, neither of which occurred. Further, the petitioner argued that restrictions on movement must be specific in scope, targeting those who may disturb the peace, and cannot be applied broadly against the public in general. When imposing restrictions, the State must choose the least restrictive measures and balance the safety of people with the lawful exercise of their fundamental rights, which did not occur here. Concerning the internet shutdown, the petitioner argued that internet restrictions did not merely affect freedom of expression but also the right to trade as well as the ability of political representatives to communicate with their constituents.

- the petition was withdrawn at some state, but the court noted that it argued that the restrictions caused broad harm even to regular and law-abiding citizens. India’s Attorney General and Solicitor General defended the restrictions.

The Attorney General argued that the restrictions were a measure to prevent terrorist acts and were justified considering the history of cross border terrorism and internal militancy that had long plagued the State of Jammu and Kashmir. The Attorney General recalled that similar steps had been taken in the past, for example, in 2016 after a terrorist had been killed there.

The Solicitor General reiterated the historical necessity argument and noted that a State’s first and foremost duty is to ensure security and protect the citizens’ lives. He also argued that the facts laid down by the petitioners were false and exaggerated the effects of the restrictions. Particularly, he noted that individual movement had never been restricted, that restrictions were imposed only in certain areas and were relaxed soon after, and that all newspapers, television and radio channels were functioning.

Further, the Solicitor General argued that even before the Constitutional Order for abrogating Article 370 had been issued, the issue was a subject of speculation in Jammu and Kashmir, including provocative speeches and messages. Accordingly, government officers on the ground decided that the restrictions were necessary, and courts have limited jurisdiction to question their judgment since issues of national security were at stake.

Specifically, concerning the communications and internet shutdown, the Solicitor General submitted that the internet was never restricted in the Jammu and Ladakh regions. He added that social media, which allowed people to send messages and communicate with a number of people at the same time, could be used as a means to incite violence. According to him, the internet allowed for the transmission of false news or fake images, which were then used to spread violence. Further, he claimed that the “dark web” allowed individuals to purchase weapons and illegal substances easily.

The Solicitor General rejected the argument that free speech standards as they related to newspapers applied to the internet on the grounds that their differences were too great. He explained that while newspapers only allowed one-way communication, the internet made it possible to communicate in both directions, making dissemination of messages very simple. He concluded that it was not possible to ban only certain websites or parts of the Internet while allowing access to other parts, as the government learned in 2017.

Decision Overview

The Supreme Court began by stating that in light of the facts of the present case, the objective of the Court was to “to strike a balance between the liberty and security concerns so that the right to life is secured and enjoyed in the best possible manner,” and leave the “propriety” of the orders at issue for “democratic forces to act on.” [para. 1]

The Court then identified five issues from the arguments presented by the petitioners and the government:

- Whether the Government can claim exemption from producing all of the restriction orders?

- Whether freedom of speech and expression and freedom to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business over the Internet is a part of the fundamental rights protected by Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution?

- Whether the Government’s action of prohibiting internet access is valid?

- Whether the imposition of movement restrictions under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure was valid?

- Whether the freedom of the press of the Petitioner in W.P. (C) No. 1031 of 2019 was violated due to the restrictions?

The five issues above were analyzed by the Court in four sections:

- Whether the Government can claim exemption from producing all the orders for the restrictions?

The Court held that the State had to produce the orders imposing the restrictions. It began by noting the difficulty it had experienced in determining the legality of the restrictions when the authorities had refused to produce the orders imposing the said restrictions. Citing the precedent in Ram Jethmalani v. Union of India , (2011) 8 SCC 1, the Court explained that the State had an obligation to disclose information in order to satisfy the right to remedy as established in Article 32 of India’s Constitution. Furthermore, Article 19 of India’s Constitution had been interpreted to include the right to information as an important part of the right to freedom of speech and expression. The Court added, “a democracy, which is sworn to transparency and accountability, necessarily mandates the production of orders as it is the right of an individual to know.” [para. 15] These fundamental rights obliged the State to act responsibly in protecting them and prohibited the State from taking away these rights casually.The Court reiterated that no law should be passed in secret because of an anticipated danger to democracy that such acts may entail. To make its point, the Court cited James Madison, “a popular government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern the ignorance and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” [para. 16]The State was thus obliged to take proactive steps to make public any law restricting fundamental rights unless there was a countervailing public interest reason for secrecy. However, even in such cases, the Court would be the body to weigh the State’s privileges against the right to information and decide what portions of the order could be hidden or redacted. In the present case, the State initially claimed privilege, but then dropped the claim and released some of the orders, explaining that all could not be released because of unspecified difficulties. For the Court, such justification was not a valid ground.

2. Did the restrictions affect freedom of movement, freedom of speech and expression and right to free trade and vocation?

First, the Court reiterated that freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 19 of India’s Constitution extended to the internet. The Court recalled its extensive jurisprudence that extended protections to new mediums for expression. In Indian Express v. Union of India , (1985) 1 SCC 641, the Supreme Court ruled that freedom of expression protects the freedom of print medium. In Odyssey Communications Pvt. Ltd. v. Lokvidayan Sanghatana , (1988) 3 SCC 410, it was held that the right of citizens to screen films was a part of the fundamental right of freedom of expression. Online expression has become one of the major means of information diffusion, and accordingly it was integral to the enjoyment of freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) , but also could also be restricted under Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

Accordingly, the Internet also plays a very important role in trade and commerce, and some businesses were completely dependent on the internet. Therefore the freedom of trade and commerce by using the internet was also constitutionally protected under Article 19(1)(g ), subject to the restrictions provided under Article 19(6). The Court, however, did not go as far as to declare the right to access the internet as a fundamental right because none of the parties to the case made that argument.The Court then discussed whether freedom of expression could be restricted and to what extent. India’s Constitution allows the Government to restrict freedom of expression under Article 19(2) as long as the restrictions were prescribed by law, were reasonable, and were imposed for a legitimate purpose. The Constitution lists an exhaustive list of reasonable restrictions that include “interests of the sovereignty, integrity, security, friendly relations with the foreign States, public order, decency or morality or contempt of Court, defamation or incitement to an offence.” [para. 31] By reviewing its jurisprudence concerning the application of Article 19(2), the Court concluded that restrictions on free speech and expression could impose complete prohibitions. In such cases, the complete prohibition should not excessively burden free speech and the government has to explain why lesser alternatives would be inadequate. Lastly, whether a restriction amounts to a complete prohibition is a question of fact to be determined by the Court on the circumstances of each case.

The Court then turned to the geopolitical context of the restrictions. It agreed with the Government that Jammu and Kashmir had long been plagued by terrorism. The Court noted that modern terrorists relied heavily on the internet, which allowed them to disseminate false information and propaganda, raise funds, and recruit others to their cause. Accordingly, the Indian authorities argued that the “war on terrorism” required imposition of the restrictions “so as to nip the problem of terrorism in the bud.” [para. 37] The Court noted that “the war on terror” was unlike territorial fights and transgressed into other forms affecting normal life, thus it could not be treated as a law and order situation.

The Court then reviewed the U.S. First Amendment and its jurisprudence from 1863 to the present day to conclude that speech which incites imminent violence is not protected. The Court highlighted that American leaders and the judiciary repeatedly restricted freedom of expression in the name of national security. The first of these cases was from 1863, Vallandigham, (Vallandigham 28 F. Cas. 874 (1863), when Mr. Vallandigham was found guilty and imprisoned during the American Civil War for publicly calling it “‘wicked, cruel and unnecessary.” In Abrams v. United States , 250 U.S. 616 (1919), Justice Holmes wrote that the power to the United States government can punish speech that produces or is intended to produce a clear and imminent danger, and that this power “undoubtedly is greater in time of war than in time of peace, because war opens dangers that do not exist at other times.” [para. 40] In Dennis v. United States , 341 US 494 (1951), the US Supreme Court held that the “societal value of speech must, on occasion, be subordinated to other values and considerations.” [para. 41] In Brandenburg v. Ohio , 395 US 444 (1969), the US Supreme Court held that the State can punish advocacy of unlawful conduct only if it intends to incite and is likely to incite “imminent lawless action.” Lastly, the Indian Court recalled that in the post 9/11 context, US Attorney General Ashcroft criticized those questioning the erosion of fundamental rights as the result of the war on terror. Specifically saying, “to those… who scare peace loving people with phantoms of lost liberty, my message is this: Your tactics only aid terrorists, for they erode our national unity and diminish our resolve. They give ammunition to America’s enemies…” [para. 44] The Court recalled that in the recent Modern Dental College & Research Centre v. State of Madhya Pradesh , (2016) 7 SCC 353 it found that no constitutional right can be claimed to be absolute considering the interconnectedness of all rights, and accordingly could be restricted. In that judgment, the Court also found that when there are tensions between fundamental rights, they must be balanced against each other so that “they harmoniously coexist with each other.” [para. 55]

Just as the First Amendment, the Indian Constitution allows the Government to restrict freedom of expression, but per the Indian Constitution such restrictions must be proportionate. The Court stressed that the standard of proportionality was key to ensuring that a right is not restricted beyond what is necessary. That said, the Court expressed caution at balancing national security with liberty and rejected the notion that a government should be prohibited from achieving a public good at the cost of fundamental rights. With this in mind, the Court defined proportionality as the question of whether “regulating exercise of fundamental rights, the appropriate or least restrictive choice of measures has been made by the legislature or the administrator so as to achieve the object of the legislation or the purpose of the administrative order, as the case maybe.” [para. 53] The Supreme Court then proceeded to conduct an extensive comparative review of proportionality tests used by Indian, German and Canadian Courts. It found that while there was agreement that proportionality was the key tool to achieve judicial balance when resolving questions of restrictions on fundamental rights, there was no agreement that proportionality and balancing were equivalent. The Court then outlined its understanding of the test of proportionality:

- The goal of the restriction must be legitimate.

- The restriction must be necessary.

- The authorities must consider if alternative measures to the restriction exist.

- The least restrictive measure must be taken.

- The restriction must be open to judicial review.

The Court added that the “degree of restriction and the scope of the same, both territorially and temporally, must stand in relation to what is actually necessary to combat an emergent situation… The concept of proportionality requires a restriction to be tailored in accordance with the territorial extent of the restriction, the stage of emergency, nature of urgency, duration of such restrictive measure and nature of such restriction.” [para. 71]

3. The legality of the Internet Shutdown

Having laid out the principles of proportionality and reasonable restrictions, the Court turned to assessing the restriction imposed on freedom of speech online. It outright rejected the State’s justification for a total ban on the internet because it lacked the technology to selectively block internet services as accepting such logic would have given the State green light to completely ban internet access every time. However, the Court conceded that there was “ample merit in the contention of the Government that the internet could be used to propagate terrorism thereby challenging the sovereignty and integrity of India” and thus it had to determine the extent to which the restriction burdened free speech. [para. 76]

The Court highlighted that it had to consider both procedural and substantive elements to determine the Constitutional legality of the internet shutdown. The procedural mechanism has two components. First, there is the contractual component between Internet Service Providers and the Government. Second, there is the statutory component as enshrined under the Information Technology Act , 2000, the Code of Criminal Procedure , 1973 and the Telegraph Act . In its analysis, the Court focused largely on the latter as it directly applied to the case at hand.

The Suspension Rules under Section 7 of the Telegraph Act were passed in 2017 and allowed the government to restrict telecom services, including access to the internet, subject to certain safeguards. These safeguards were that first, the suspension orders may be issued only by the Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of Home Affairs or by the Secretary to the State Government in charge of the Home Department. In unavoidable circumstances another official not below the rank of a Joint Secretary to the Government of India may issue the orders provided that the competent authority approves the orders within 24 hours of its issuance. Without approval the suspension must be lifted within 24 hours. The orders must include reasons for the suspension and its copy must be sent to a Review Committee consisting of senior State officials. The reasons should not only explain the necessity of the suspension but also the “unavoidable” circumstance which necessitated the order.

Furthermore Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act permitted suspension orders only in a situation of public emergency or in the interest of public safety. The Court thus found that to issue a suspension order, the Government first had to determine that a public, and not any kind of other, emergency existed. “Although the phrase “public emergency” has not been defined under the Telegraph Act , it has been clarified that the meaning of the phrase can be inferred from its usage in conjunction with the phrase “in the interest of public safety” following it.” [para. 92]

The Supreme Court noted that the definition of an emergency varies. For example, “ Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, notes that ‘[I]n time of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed…’. Comparable language has also been used in Article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights which says “In time of war or other public emergency threatening the life of the nation”. We may only point out that the ‘public emergency’ is required to be of serious nature, and needs to be determined on a case to case basis.” [para. 93]

Although the Suspension Rules do not provide for publication or notification of the orders, the Court noted that public availability of a government order is a settled principle of law and of natural justice, particularly if an order affects lives, liberty and property of people. The Court reiterated that Article 226 of India’s Constitution grants an aggrieved person the constitutional right to challenge suspension orders.

Finding it necessary, the Court once again reiterated that “complete broad suspension of telecom services, be it the Internet or otherwise, being a drastic measure, must be considered by the State only if ‘necessary’ and ‘unavoidable’. In furtherance of the same, the State must assess the existence of an alternate less intrusive remedy.” [para. 99]

The Court noted that the Suspension Rules do not indicate the maximum duration of a suspension order. Nonetheless, considering the principle of proportionality, the Court opined that indefinite suspension is impermissible. Since the Suspension Rules were silent on the length of a permissible shutdown, the Court found that it was up to the Review Committee to determine its duration and to ensure that it would not extend beyond a period which was necessary.

The State submitted eight orders to the Court. Four were passed by the Inspector General of the Police and the other four by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. The Solicitor General explained that the authorities relaxed some restrictions but were continuously appraising the situation on the ground. The Court conceded that the danger to public safety could not be ignored, but noted that any new restrictions would have to be imposed on the basis of a new order. Since the Court could not view all orders to understand which were no longer in effect and could not assess the public order situation, it “moulded the relief in the operative portion.” [para. 102]

4. Restrictions Under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure Code

The Petitioners argued that to justify restrictions under Section 144 of the Cr.P.C, the State had to prove that there “would be an action which will likely create obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person or will likely cause disturbance of the public tranquility, and the Government could not have passed such orders in anticipation or on the basis of a mere apprehension.” [ para. 103] The State argued that “the volatile history, overwhelming material available even in the public domain about external aggression, nefarious secessionist activities and the provocative statements given by political leaders, created a compelling situation which mandated passing of orders under Section 144.” [ para. 104]

The Court noted that Section 144 is one of the mechanisms that enable the State to maintain public peace and it could be invoked in urgent cases of nuisance or perceived danger. Thus, it allows the State to take preventive measures to deal with imminent threats to public peace. The Section contains several safeguards to prevent its abuse, including an assessment by a magistrate to conclude that there were sufficient grounds for restrictions under the section, identification of a person(s) whose rights may be restricted, and determining the length of the restriction.

Judicial precedent established that restrictions under Section 144 cannot be imposed merely because there was likelihood or tendency of danger, but only to immediately prevent specific acts that may lead to danger. The restriction could be imposed on an entire area if it contains groups of people disturbing public order. Indefinite restrictions under Section 144 are unconstitutional. Orders passed under Section 144 were executive orders subject to judicial review under Article 226 of the Constitution. The State cannot impose repetitive orders, which would be an abuse of power.

The Petitioners also argued that maintaining “law and order” would warrant a narrower set of restrictions than “public order,” under Section 144. The Supreme Court agreed that the notions of “public order” and “law and order” differed, with the latter being the broadest. The Court described the differences as concentric circles with law and order representing the largest circle “within which is the next circle representing public order and the smallest circle represents security of State.” [para. 120] Allowing the imposition of restrictions to protect law and order would thus broaden the authority of the government to impose restrictions. Further, not all disturbances of law and order undermined public order.

The Court, however, agreed that there may be times when it is impossible to distinguish between the individuals who may break public order and those who do not pose a threat. “A general order is thus justified but if the action is too general, the order may be questioned by appropriate remedies for which there is ample provision in the law.” [para, 124]

Nevertheless, the Court noted that “orders passed under Section 144 , Cr.P.C . have direct consequences upon the fundamental rights of the public in general. Such a power, if used in a casual and cavalier manner, would result in severe illegality.” [para. 129] Thus, it is imperative to indicate the material facts necessitating the passing of such orders. The Court conceded that the State is best placed to assess threats to public order, but it had to exhibit the material facts to justify an order under Section 144 to enable judicial scrutiny and verification of the order’s legitimacy. A key consideration is the perceived imminence of the threat and whether invoking Section 144 was the proper remedy to prevent potential harm. Magistrates must balance the the right and restriction on the one hand against the right and duty on the other, and any restrictions must be proportionate, i.e. “never allowed to be excessive either in nature or in time.” [para. 39] Further, “[o]rders passed mechanically or in a cryptic manner cannot be said to be orders passed in accordance with law.” [para. 134]

Although the restrictions may have been removed, the Court stated that it cannot ignore noncompliance with the law in this case, as the issue at hand is not just about what happened in Jammu and Kashmir but also about imposing a check on the State. The Court reiterated that a government must follow the law if it feels that there is a threat to public order.

Thus, the Court concluded that the power under Section 144 could be exercised “not only where there exists present danger, but also when there is an apprehension of danger. However, the danger contemplated should be in the nature of an ‘emergency’ and for the purpose of preventing obstruction and annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed.” [para. 140] The power cannot be used to suppress legitimate expression and should be used only in the presence of material facts justifying its application.

5. Freedom of the Press

The Court rejected the Petitioners’ arguments that the restrictions on movement and communication imposed in Jammu and Kashmir directly curtailed freedom of the press and journalists’ ability to perform their professional duties. The Court began by highlighting the importance of freedom of the press. It recalled that as early as in 1914, the freedom of the press had been recognized in India. In Channing Arnold v. The Emperor , (1914) 16 Bom LR 544, the Privy Council stated that: “the freedom of the journalist is an ordinary part of the freedom of the subject and to whatever length, the subject in general may go, so also may the journalist, but apart from the statute law his privilege is no other and no higher. The range of his assertions, his criticisms or his comments is as wide as, and no wider than that of any other subject.” [para. 142] It was thus not doubted that the freedom of the press is a valuable and sacred right protected by the Indian Constitution.

The Court interpreted the Petitioners to claim that the imposed restrictions did not necessarily have a direct but rather an indirect as well as a chilling effect on their freedom of expression. However, the Court found that the Petitioners failed to offer evidence that the restrictions restricted the publishing of newspapers in Jammu and Kashmir or to challenge the State’s argument that newspapers were published and distributed during the communication and movement lockdown. “In view of these facts, and considering that the aforesaid Petitioner has now resumed publication, we do not deem it fit to indulge more in the issue other than to state that responsible Governments are required to respect the freedom of the press at all times. Journalists are to be accommodated in reporting and there is no justification for allowing a sword of Damocles to hang over the press indefinitely.” [para. 151]

Conclusions

Based on the above the Court found that:

- Freedom of expression and the freedom to practice any profession online was protected by India’s Constitution

- Although the Government could suspend the Internet, the government had to prove necessity and impose a temporal limit, which it failed to do in this case. Thus, the government had to review its suspension orders and lift those that were not necessary or did not have a temporal limit.

- Restrictions under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure could not be used to suppress legitimate expression and are subject to judicial scrutiny. The Court thus ordered the State to review its restrictions.

Decision Direction

Decision Direction indicates whether the decision expands or contracts expression based on an analysis of the case.

Mixed Outcome

Although the Court did not go as far as to lift the restriction on internet and movement, its judgment still expanded freedom of expression by reiterating that internet access was integral to freedom of expression and could not be restricted indefinitely even in the name of national security. The Court thoroughly outlined the principles and tests to strike a balance between fundamental rights and national security. Just as importantly, the Court stressed that orders that impact fundamental rights such as freedom of expression cannot be passed arbitrarily and in secret, but must be available to the public and subject to judicial scrutiny.

The Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) has listed a range of negative aspects of the ruling , namely that the “Court has allowed the State to get away with frustrating the fundamental right to judicial review by unjustifiably witholding orders,” those that have suffered losses under the shutdown have no recourse or remedy, and under specific circumstances, a complete prohibition of speech could be considered as “reasonable.” Of particular note, the Court rejected the argument that journalists’ freedom of the press had been curtailed. As IFF wrote, “[t]he direct and inevitable consequence of disabling telecom services and physically stopping journalists from entering certain areas is violation of press freedom and it cannot be characterized solely as a chilling effect.”

Global Perspective

Global Perspective demonstrates how the court’s decision was influenced by standards from one or many regions.

Table of Authorities

Related international and/or regional laws.

- ICCPR, art. 4

- ECHR, art. 15.

National standards, law or jurisprudence

- India, Constitution of India (1949), art. 19.

- India, Code of Criminal Procedure, sec. 144

- India, Indian Telegraph Act of 1885, sec. 5.

- India, Ram Jethmalani & Ors. v. Union of India, (2011) 8 SCC 1

- India, Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) Private Ltd. v. Union of India, (1985) 2 S.C.R. 287

- India, Odyssey Communications Ltd. v. Lokvidayan Sanghatana, 3 SCC 410 (1988)

- India, Modern Dental College & Research Centre v. State of Madhya Pradesh (2016), 7 SCC 353.

- India, Channing Arnold v. The Emperor, (1914) 16 Bom LR 544.

Other national standards, law or jurisprudence

- U.S., Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951)

- U.S., Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919)

- U.S., Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969)

- U.S., Ex parte Vallandigham, 28 F. Cas. 874.

Case Significance

Case significance refers to how influential the case is and how its significance changes over time.

The decision establishes a binding or persuasive precedent within its jurisdiction.

The decision was given by a three-judge bench of the Indian Supreme Court. Therefore, it establishes a binding precedent on all Courts within its jurisdiction, unless overruled by a larger bench of the Supreme Court.

The decision was cited in:

Foundation for media professionals v. union territory of jammu and kashmir & anr..

- T. Ganesh v. Union of India

- Navalakha v. Union of India

- Manohar v. Union of India

- Ashlesh Biradar v. State of West Bengal

- Raju Prosad Sarma v. State of Assam

- Unwanted Witness-Uganda v. Attorney General

- Software Freedom Law Center, India v. State of Arunachal Pradesh & Ors

- A Lakshminarayanan v. Assistant General Manager HRM

- Software Freedom Law Center, India (SFLC.in) v. State of Jharkhand

Official Case Documents

Reports, analysis, and news articles:.

- The Guardian, India supreme court orders review of Kashmir internet shutdown https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/10/kashmir-blackout-indias-supreme-court-orders-delhi-to-review-internet-shutdown

- India’s Supreme Court Orders a Review of Internet Shutdown in Kashmir. But For Now, It Continues https://time.com/5762751/internet-kashmir-supreme-court/

- Sflc.in, SC judgment – Safeguards for shutdown, limited relief for Kashmir https://sflc.in/sc-judgment-safeguards-shutdown-limited-relief-kashmir

- TechCrunch, India’s top court rules indefinite internet shutdown in Kashmir unwarranted and amounts to abuse of power https://techcrunch.com/2020/01/10/internet-shutdown-supreme-court-india-kashmir/

- Media Nama, The devil’s in the (future) detail: The Supreme Court’s internet shutdown judgment https://time.com/5762751/internet-kashmir-supreme-court/

- Internet Freedom Foundation, SC's Kashmir communication shutdown judgement is just the beginning of a long uphill campaign https://internetfreedom.in/scs-judgement-on-kashmir-communication-is-just-the-beginning/

- Why SC order on Internet goes beyond J&K, opens window for challenges and judicial reviews https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/jammu-and-kashmir-internet-shutdown-curbs-supreme-court-6210725/

- SC order on internet lockdown in J&K makes right noises but leaves matters of relief to the future https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/jammu-and-kashmir-internet-shutdown-supreme-court-article-370-6210489/

- As 2G returns to Kashmir after 5 months, these are some strong arguments against internet shutdowns in the future https://www.businessinsider.in/india/news/as-2g-returns-to-kashmir-after-5-months-these-are-some-strong-arguments-against-internet-shutdowns-in-the-future/articleshow/73266751.cms

Attachments:

Have comments.

Let us know if you notice errors or if the case analysis needs revision.

Send Feedback

Related Posts

Access to public information, content regulation / censorship, internet shutdowns, national security.

June 25, 2020

Amnesty International Togo and Ors v. The Togolese Republic

Public safety

Access to Public Information, Internet Shutdowns, National Security

May 11, 2020

Related News

Digital rights, access to public information, content regulation / censorship, freedom of association and assembly / protests, hate speech, national security, privacy, data protection and retention.

March 16, 2021

Jurisprudence Relating to COVID-19

Digital rights, press freedom, access to public information, freedom of association and assembly / protests, national security, political expression.

August 23, 2021

IFEX Regional Spotlights

Supreme Court judgment on Freedom of Press and its significance – Explained, pointwise

ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 10th August. Click Here for more information.

- 1 Introduction

- 2 About the recent SC judgment on Freedom of Press

- 3 What are the different views of the Supreme Court on freedom of press in the past?

- 4 What is the significance of the recent judgment on Freedom of Press?

- 5 How is Freedom of the Press regulated in India?

- 6 What are the challenges in ensuring Freedom of Press?

- 7 What should be done further to ensure Freedom of Press?

| For Archives click → |

Introduction

The Supreme Court of India’s recent judgment ordered the restoration of the broadcasting license of MediaOne, a Kerala-based television channel. It is considered as a significant victory for the freedom of the press. The ruling has highlighted the mounting political and economic pressures faced by the Indian media and the need for further measures to ensure press freedom.

About the recent SC judgment on Freedom of Press

What are the different views of the Supreme Court on freedom of press in the past?

Romesh Thapar v. State of Madras (1950): The SC held that freedom of speech and expression includes freedom of the press. The Court observed that the press has a significant role to play in informing the public and promoting democratic values. Therefore, any attempt to curtail the freedom of the press would violate the right to freedom of expression.

Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi (1950): The SC held that freedom of the press cannot be curtailed unless there is an imminent danger to public safety. The Court observed that any attempt to restrain the press must be based on clear and present danger, and not on vague or remote possibilities.

Indian Express Newspapers v. Union of India (1985): The Court emphasized the importance of freedom of the press in these words: “The expression freedom of the press has not been used in Article 19 but it is comprehended within Article 19(1)(a). The expression means freedom from interference from an authority, which would have the effect of interference with the content and circulation of newspapers. There cannot be any interference with that freedom in the name of public interest.”

Siddhartha Vashisht v State NCT of Delhi (2010): The court made the important distinction between trial by media and informative media. The case of Sahara vs SEBI is a review of the case law on the point, and it reinforces the line between legitimate comment and usurpation that affects the presumption of innocence.

Manohar Lal Sharma v Union of India,( 2021): The SC recognised the link between the Right to Privacy and Freedom of Speech, noting that a breach of privacy can lead to self-censorship. They said that press freedom and privacy were allies and that the fear of surveillance is an ‘assault’ on the press, which is the fourth pillar of democracy.

Vinod Dua v. Union of India & Others (2021): The SC held that criticism of the government and its policies is not seditious and that the right to free speech and expression extends to the press.

What is the significance of the recent judgment on Freedom of Press?

Upholding the freedom of the press: The Supreme Court’s judgment has upheld the freedom of the press as a fundamental right guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. This is significant as it reaffirms the importance of the press as a watchdog of democracy.

Curtailing government overreach: The judgment has put a check on the government’s ability to use vague allegations and opaque claims of intelligence-based evidence to restrict the freedom of the press. This is significant as it ensures that the government cannot curtail press freedom at will, and must provide concrete evidence of wrongdoing before taking action.

Setting a precedent for future cases: The judgment sets a precedent for future cases involving press freedom in India. It establishes that journalists and media organizations have the right to access vital evidence the prosecution plans to use, and that critical coverage of the government cannot be deemed unacceptable.

Protecting the rights of journalists: The judgment is significant in that it protects the rights of journalists who have been arrested or censored by the government under the pretext of national security concerns. It ensures that journalists are not unduly targeted or harassed by the state, and that their rights to free speech and expression are protected.

Strengthening democracy: The judgment strengthens democracy in India by ensuring that the press can function as an independent and critical voice. A free and independent press is essential to a functioning democracy, as it holds those in power accountable and enables citizens to make informed decisions

How is Freedom of the Press regulated in India?

Constitutional guarantee: The Constitution of India guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression 19(1)(a) , which includes the freedom of the press. This means that the government cannot outrightly ban or censor the media without sufficient cause. Article 19(2 ) provides several reasons to curtail free speech “in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence”.

Laws and regulations: However, there are laws and regulations in place that impose restrictions on the media. For example, the Official Secrets Act, 1923 , allows the government to classify certain information as secret and to punish those who disclose it. Similarly, the Press and Registration of Books Act, 1867 , requires publishers to register with the government and imposes penalties for non-compliance.

Self-regulatory mechanisms: The media in India is also subject to self-regulatory mechanisms such as the Press Council of India . This body oversees the conduct of the press and handles complaints against it. It consists of journalists and representatives from the media industry and is meant to act as a watchdog for the press.

What are the challenges in ensuring Freedom of Press?

Political pressure and censorship: The Indian government has been known to put pressure on the media to report in a certain way, and has been accused of censoring content critical of the government.

Violence against journalists : India has a high rate of violence against journalists, with many cases of physical assault, harassment, and even murder reported each year. For example, in 2017, a journalist was shot and killed outside her home in Bangalore, reportedly for her critical reporting on right-wing politics.

Legal challenges: There are several laws in India that can be used to restrict press freedom, including the Official Secrets Act and defamation laws. Journalists who report on sensitive issues can face arrest, detention, or other legal action. For example, in 2020, a journalist was arrested and charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for his reporting on the Hathras rape case.

Financial pressures: The media industry in India is subject to financial pressures that can impact its ability to report freely. For example, media outlets may rely on advertising revenue from the government or corporate entities, which can create conflicts of interest and limit their reporting on certain issues.

Misinformation and propaganda : The rise of social media and digital platforms has led to an increase in misinformation and propaganda, which can make it difficult for audiences to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources. This can have a chilling effect on journalists, who may be hesitant to report on sensitive issues for fear of being accused of spreading “fake news.”

What should be done further to ensure Freedom of Press?

Strengthening Legal Protections : The government should review and amend existing laws to ensure that they do not unduly restrict press freedom. There is also a need to enact stronger legal protections for journalists and media outlets, including laws that specifically criminalize violence against journalists.

Promoting Media Pluralism : Steps should be taken to promote media pluralism, including increasing the diversity of ownership, funding models, and content. The government should also support the growth of community and alternative media.

Encouraging Self-Regulation : Media outlets should be encouraged to adopt and adhere to voluntary codes of conduct and ethics. Self-regulation can be effective in promoting responsible journalism and holding media organizations accountable.

Fostering a Culture of Openness : The government should foster a culture of openness and transparency, including by providing greater access to information and data. This can help to promote public trust in the media and the government.

Protecting Whistleblowers: The government should enact stronger protections for whistleblowers who reveal information in the public interest. This can help to ensure that journalists have access to important information and can report on issues of public concern without fear of reprisal.

Supporting Media Literacy: There is a need to promote media literacy among the general public, including by providing education and resources that can help people to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources of information. This can help to promote a more informed and engaged citizenry.

Sources : The Hindu , Indian Express ( Article 1 and Article 2 ), Times of India ( Article 1 and Article 2 ), Hindustan Times , The Quint and The Print

Syllabus : GS 2: Indian Constitution and Polity – Indian Constitution—historical underpinnings, evolution, features, amendments, significant provisions and basic structure.

Type your email…

Search Articles

Prelims 2024 current affairs.

- Art and Culture

- Indian Economy

- Science and Technology

- Environment & Ecology

- International Relations

- Polity & Nation

- Important Bills and Acts

- International Organizations

- Index, Reports and Summits

- Government Schemes and Programs

- Miscellaneous

- Species in news

All India Open Test(Simulator X)

11 years 🥳 of Publication

- Law Firm & In-house Updates

- Read to know

Landmark Judgement on Freedom of Press

Indian Express v. Union of India: [1]

Petitioner: Indian Express

Respondent: Union of India

the petitioner for this situation were corporate organizations, workers, and shareholders thereof, and trusts which are part of the publication of newspapers. The import duty in the newspapers was challenged. Under the Customs Tariff Act, 1975, and the duty under Finance Act 1981. Preceding this news, the newspaper enjoyed exemption from customs duty. And also, the newspapers were classified into small, medium, and large which encroaches article 14 of the Constitution (equality before law).

The issue was raised imposition of a duty would adversely affect the expenses and dissemination and, hence the crippling effect on freedom of expression under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution and freedom of trade under Article 19(1)(g).

The Supreme Court of India held that the government of India has the power to imply taxes affecting the publication of newspapers and it also said that classifying the industry into small, medium, and large have rational nexus of fulfilling the objective of taxation and is not arbitrary. For the implication of duty, it was said that the press plays a crucial role in a democratic machinery. The courts have a duty to uphold the freedom of the press and invalidate all laws and administrative actions that bridge that freedom. And it was realized that freedom of the press has three essential elements:

Freedom of access to all sources of information

Freedom of publication

Freedom of circulation

Conclusion: The Supreme Court of India directed the central government to look into its taxation policies by acknowledging that it causes a burden on newspapers. It was argued that increased cost on newspapers would drop a circulation affecting the freedom of speech and expression. The court reasoned that the government has the power to put taxes but within fair limits so that freedom of expression does not get encroached.

Union of India v. Assn. for Democratic Reforms [2]

Petitioner: Union of India

Respondent: Assn. for Democratic Reforms

The Association of Democratic Reforms filed a petition with the High Court of Delhi to impel enforcement of certain recommendations related to how to make the electoral process in India more reasonable, transparent, and equitable. It was appealed by the Government of India that these recommendations were produced by the law commission and provided that the election commission needs to disclose information of personal background to the public including criminal history, educational qualifications, personal financial details, and other necessary information for determining candidate’s capacity and capability. The Union of India challenged the decision through an appeal to the Supreme Court of India, arguing that the Election Commission and the High Court did not have such powers and that voters did not have a right to such information.

It was held by Supreme Court of India that:

“One-sided information, disinformation, misinformation, and non-information, all equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce. Freedom of speech and expression includes the right to impart and receive information which includes freedom to hold opinions”.

Sakal Papers Ltd. V. Union of India [3]

Petitioner: Sakal Papers Ltd.

Sakal newspapers were published by a private company. The company with two shareholders and two readers filed a petition in Supreme Court against the state. It was challenged by the company that constitutional validity of the Newspaper (Price and Page) Act, 1956 which was granted power by the Central Government to regulate the price of newspapers by relating it to their pages and allocation of space for advertising matter.

Issue raised:

The petitions argued that Newspapers (Price and Page) Order, 1960, and Newspaper order is infringing the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) of the constitution.

Decision Held:

The supreme court held that Newspaper (Price and Page) Act, 1956, and the Daily Newspapers (Price and Page) Order, 1960 violated the constitutional right to speech. It was said that the laws made violate the right of speech and expression by restricting the number of pages and prices, it also violates article 19(2) as it does not come under reasonable restrictions. The court struck down the decision on the ground that it would help the small newspapers to grow.

Bennett Coleman and Co. V. Union of India: [4]

Petitioner: Bennett Coleman and Co.

Date of judgment: 30 th Oct. 1972

The petitioners were media companies dealing with the publication of newspapers. The company challenged the import duties under Import Control Order 1955 and further, the Newsprint Policy of 1972-73 came with more restrictions which had four features:

1. No new newspapers may be started by establishments owning more than two newspapers if at least one of which is daily;

2. The total number of pages may not exceed ten;

3. The increase in the number of pages may not be more than 20% for newspapers that are under ten pages;

4. No-interchangeability of newsprint may permit between different newspapers of the same establishment or between different editions of the same paper.

The petitioners were restricted to make circulation under newsprint policies in quota limit and it was violative of Article 19(1)(a). the respondent gave a counter comment that companies do not enjoy fundamental rights, as it is available only to natural persons. As per the restrictions placed were fair.

Issues raised:

· Whether the petitioners being companies could invoke fundamental rights?

· Whether the restriction on newsprint import under the 1995 order was violative of Art. 19 (1) (a) of the constitution?

· Whether the newsprint Policy fell within clause 5(1) of the Import, Control Order 1955 and was valid?

· Whether clauses 3 and 3A of clause 3 of the 1962 Newsprint Order were violative of Arts. 19(1) (a) and 14 of the Constitution?

The judgment was delivered by J. Ray and it was said that petition was maintainable. Being a company does not restrict them to claim relief for violation of rights of shareholders and editorial staff (who were petitioners) Similarly, like Sakal Papers Ltd. v. Union of India the decision was struck holding it violative of Article 19 (1) (a) and Article 19 (2). The grounds were considered not reasonable.

Express Newspaper v. Union of India [5]

Petitioner: Express Newspaper

In this case, the clauses of Working Journalists (Conditions of Service) and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1965, whose object was to secure the amelioration of conditions of the working journalists and other persons employed in a newspaper establishment, was challenged as interfering with the right of freedom of Press. It was urged that as the provisions of the Act specified the wages and conditions of service of the working journalists, it would impose heavy financial burdens on the newspaper establishments, which did not have the resources to meet the new financial responsibilities and might have to close down. It had, therefore, the effect of having a direct and preferential burden on the press and had a tendency to curtail circulation and thereby narrow the scope of dissemination of information.

The court was convinced that the working conditions in the newspaper industry were not satisfactory and a lot of working conditions needs to be improved. “ Those employers who are favorably situated, may not feel the strain at all while those of them who are marginally situated may not be able to bear the strain and may inconceivable cases have to disappear after closing down their establishments. That, however, would be a consequence that would be extraneous and not within the contemplation of the Legislature. It could, therefore, hardly be urged that the possible effect of the impact of these measures inconceivable cases would vitiate the legislation as such. All the consequences which have been visualized in this behalf…would be remote and depend upon various factors which may or may not come into play. Unless these were the direct or inevitable consequences of the measures enacted in the impugned Act, it would not be possible to strike down the legislation as having that effect and operation. A possible eventuality of this type would not necessarily be the consequence which could be in the contemplation of the Legislature while enacting a measure of this type for the benefit of the workmen concerned” So the impugned legislation in attempting to ameliorate the conditions of the working journalists was characterized as directed towards the business aspect of newspaper activity and the repercussions on the news and views aspect was not of that order so as to affect adversely the right of circulation. [6]

Mahesh Bhatt v. Union of India: [7]

The writ petition filed by Mahesh Bhatt challenged the lawfulness of the provisions of the cigarette and other tobacco products. The Cigarette and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply, and Distribution) Act, 2003 defines the advertisement includes any visible representation by way of notice, circular, label, wrapper or other document and also includes any announcement made orally or by means of producing transmitting light, sound, smoke or gas.

it was held that advertisements intend to make information and advice open and scatter data through media and different methods, it was decided that advertisements of tobacco items can’t as such viewed as indecent. Utilization Consumption of tobacco or smoking is unfortunate yet isn’t unethical. The term decency is more expansive. commercial advertisements are entitled to limited protection under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution if they are in the public interest. Commercial advertisements of tobacco products are not expressions protected under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. Business ads will incorporate tobacco items. In any case, business promotions are extraordinary and different from the news. The reason and object behind news are to disperse data, ideas, and thoughts. Pre-predominant nature and character of the article, picture, and so forth, will decide if it is a business ad or a news thing/picture. Therefore, the advertisement comes into a different approach than of press.

[1] Indian Express v. Union of India, (1985) 1 S.C.C. 641 (India)

[2] Union of India v. Assn. for Democratic Reforms, A.I.R. 2001 Delhi 126 (India).

[3] Sakal Papers Ltd. V. Union of India, A.I.R. 1962 S.C. 305 (India).

[4] Bennett Coleman v. Union of India, A.I.R. 1973 S.C. 106 (India).

[5] Express Newspaper v. Union of India, A.l.R. 1958 S.C, 578 (India)

[6] D.k. Singh, Freedom of Press in India, http://14.139.60.114:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/688/34/Freedom%20of%20the%20Press%20in%20India.pdf.

[7] Mahesh Bhatt v. Union of India,147 (2008) DLT 561 (India).

You Might Also Like

How legal regulations affect your rights as an employee, highlights of new criminal laws of india, auto accidents to medical malpractice: the different types of personal injury cases, enforcement of arbitral awards, hegelian approach to intellectual property.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get our newest articles instantly!

Don’t miss out on new posts, Subscribe to newsletter Get our latest posts and announcements in your inbox.

Sign up for daily newsletter, be keep up get the latest breaking news delivered straight to your inbox., leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign in to your account

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

With raids, arrests and hostile takeovers, India press freedom continues to decline

Shalu Yadav

Border Police stand guard outside the office building where Indian tax authorities raided the BBC's office in New Delhi on Feb. 15. Sajjad Hussain/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Border Police stand guard outside the office building where Indian tax authorities raided the BBC's office in New Delhi on Feb. 15.

NEW DELHI — "I have resigned," the journalist declared in a YouTube video last November. "You won't hear me on NDTV anymore saying, 'Hello, I'm Ravish Kumar.'" And with that, the longtime face of New Delhi Television, one of India's oldest news broadcasting channels, stepped down.

Ravish, 48, had been with NDTV for 26 years. At the time of his resignation, he was senior executive editor at the news outlet, known for its fierce and critical coverage of government policies and citizens' voices.

How Asia's ex-richest man lost nearly $50 billion in just over a week

But since last August, when Gautam Adani, a controversial magnate, announced his move to acquire the channel in a hostile takeover, anxiety in the newsroom grew — as did the departures of network leaders like Ravish.

Indian journalist Ravish Kumar delivers a lecture on Sept. 6, 2019, in Manila, Philippines. Kumar, one of India's best-known TV figures, resigned from the NDTV channel after a business magnate with close ties to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose government has chipped away at press freedoms, announced his move to acquire the channel. Bullit Marquez/AP hide caption

Indian journalist Ravish Kumar delivers a lecture on Sept. 6, 2019, in Manila, Philippines. Kumar, one of India's best-known TV figures, resigned from the NDTV channel after a business magnate with close ties to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose government has chipped away at press freedoms, announced his move to acquire the channel.

Adani, who is closely associated with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is the founder of the Ahmedabad-based Adani Group, India's largest port operator and largest coal trader. After a recent report by Hindenburg Research accused Adani Group companies of decades of stock manipulation and accounting fraud, the prime minister has tried to distance himself from the tycoon's controversies. (Adani has denied wrongdoing ).

Adani has said that NDTV would remain independent under his ownership and would call out the government when it has "done something wrong."

But his critics are not convinced.

"Much of Adani's wealth has been a direct result of this problematic relationship [with the prime minister]. ... So, it's only expected that an Adani-owned channel would work to keep up the Modi-Adani ties," says Somdeep Sen, a political scientist at Roskilde University in Denmark.

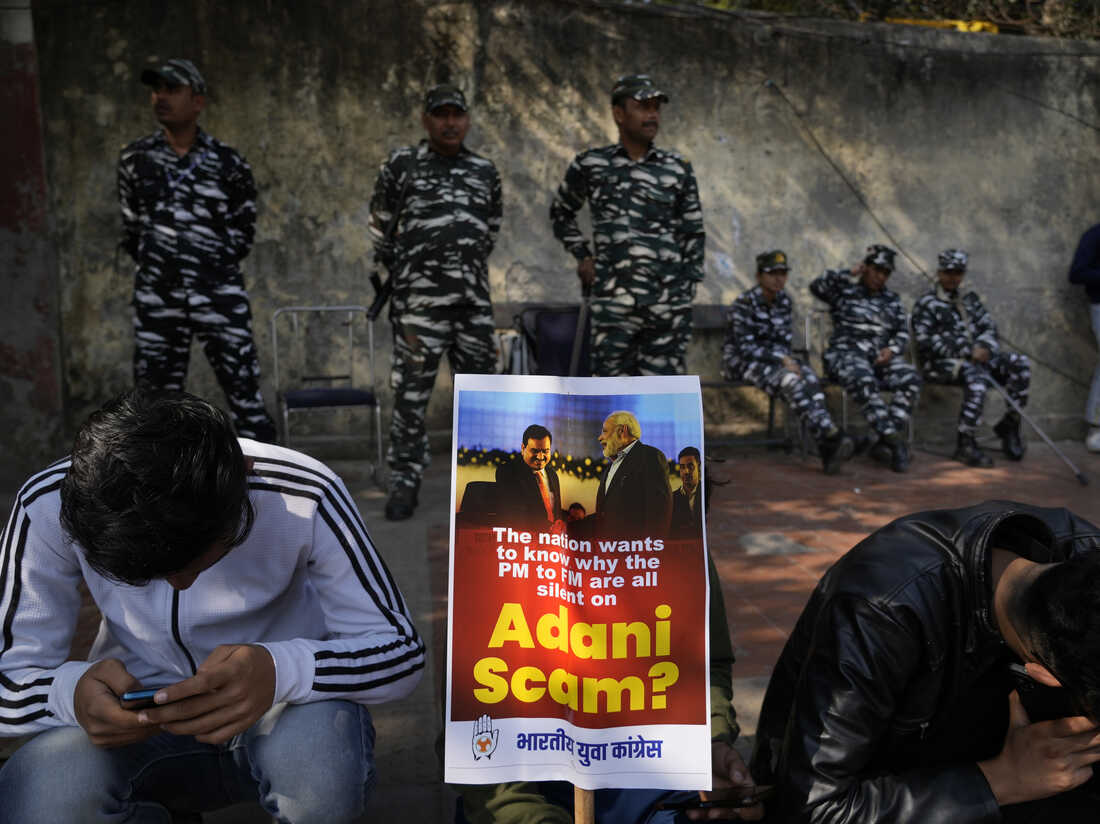

Members of opposition Congress party, demanding an investigation into allegations of fraud and stock manipulation by India's Adani Group, display a placard with images of Indian businessman Gautam Adani and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a protest in New Delhi, Feb.6. Manish Swarup/AP hide caption

Members of opposition Congress party, demanding an investigation into allegations of fraud and stock manipulation by India's Adani Group, display a placard with images of Indian businessman Gautam Adani and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a protest in New Delhi, Feb.6.

Press freedoms are among other rights being squeezed in India

Conglomerates' takeovers of media outlets are not unique to India. But New Delhi-based historian Mukul Kesavan, who is also an independent journalist, says Indian media takeovers by Modi government allies are "symptomatic of a larger malaise" posing threats to rights.

Opinion: India expelled me for journalism 47 years ago. It's still cracking down

"It would be a mistake to look at the takeover of NDTV as a thing in itself. I think it's part of a much larger battering down on basic, fundamental, democratic rights — the right to organize, the right to protest, the right to march, the right to speak and the right to publish," says Kesavan.

According to Amnesty International, Indian authorities are increasingly imposing unlawful and politically motivated restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly. (Amnesty International was itself targeted by Modi's government, and was forced to shut its India operations in 2020 ).

The rights organization has repeatedly flagged authorities' targeting of journalists , coupled with a broader crackdown on dissent that "has emboldened Hindu nationalists to threaten, harass and abuse journalists critical of the Indian government."

Indian authorities accuse the BBC of tax evasion after raiding their offices

The latest journalist to be arrested was Irfan Mehraj, a reporter from Jammu and Kashmir, who was picked up on March 20 in connection with a "terror funding case."

Amnesty termed Mehraj's arrest "a travesty and yet another instance of the long-drawn repression of human rights." Kashmiri journalists have long been targeted by the Indian government.

Some major Indian digital outlets remain independent

Soon after Modi became prime minister in 2014, NDTV's biggest competitor, Network 18, was acquired by Mukesh Ambani, another of Modi's billionaire allies. Since then, Ambani has become the boss of more than 70 outlets across the country, with a combined weekly audience of at least 800 million viewers.

Kesavan says that most Indian media houses have become defenders of the Hindu nationalist government, selling the majoritarian populist agenda.

"What's left," Sen says, "is a few major [digital] outlets that are independent. If this trend continues, the future is grim for Indian democracy."

In January, the government proposed new rules for digital media, which would ban content the government judges to be "fake or false."

The Indian government recently targeted the BBC

Worries intensified in February, when India's tax authorities raided the BBC's offices in Delhi and Mumbai and, after three days of search, accused the British broadcaster of evading taxes.

A group of students shout anti-government slogans as they are not allowed to screen a BBC documentary at Delhi University, Jan. 27. Tensions escalated at the university after a student group said it planned to screen the documentary examining Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's role during 2002 anti-Muslim violence, prompting dozens of police to gather outside campus gates. Manish Swarup/AP hide caption

A group of students shout anti-government slogans as they are not allowed to screen a BBC documentary at Delhi University, Jan. 27. Tensions escalated at the university after a student group said it planned to screen the documentary examining Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's role during 2002 anti-Muslim violence, prompting dozens of police to gather outside campus gates.

The raid took place less than a month after the BBC released a documentary critical of Modi and alleged his responsibility in anti-Muslim violence that left more than 1,000 dead and tens of thousands displaced in Gujarat in 2002, when he was serving as chief minister of the state. The Indian Supreme Court has cleared Modi of responsibility.

The government banned the BBC documentary from airing in India and used emergency laws to force Twitter and YouTube to take down clips.

Pro-government media outlets cast doubt on the BBC's credibility . A spokesperson for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party called the BBC "the most corrupt organization which has little regard for India's constitution while it works from here," while other officials called the documentary "hostile propaganda" and "anti-India garbage" with a "colonial mindset."

India's foreign minister, S. Jaishankar, q uestioned the timing of the documentary release — a year before India's next national elections — and alleged that the documentary was part of an attempt to "shape a very extremist image" of India and its prime minister.

A government adviser denied that the tax search was related to the documentary.

The Press Club of India said the raid was a "clear cut case of vendetta."

Jyoti Malhotra, a Delhi-based media critic, says everyone in India knows what a tax search means. "What they're saying is that you better fall in line," she explains. "This is not the first time that a media organization has been raided. What's surprising is that they went after a foreign organization, BBC, which is a household name in India and has a reputation for fairness and objectivity."

India's press freedom rankings have dropped

Since Modi became prime minister in 2014, India has slipped in rank from 140 to 150 in the World Press Freedom Index of 180 countries compiled by Reporters Without Borders.

But Sen says the Indian public seems largely unmoved by the weakening of the fourth pillar of democracy — a result of what he calls Modi's "overbearing, cult-like presence in everyday India."

"It is the cult of personality that has been the potent political tool of the government that has allowed it to weather a string of controversies and large-scale political and governance failures," he says. "So, I am not surprised that Modi has been so proactive in suppressing dissent as a way of maintaining this cult of personality."

- press freedom

- journalists

- India press freedoms

- Law of torts – Complete Reading Material

- Weekly Competition – Week 4 – September 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 1 October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 2 – October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 3 – October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 4 – October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 5 October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 1 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 2 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 3 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 4 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 1 – December 2019

- Sign in / Join

- Constitution

- Constitutional law

The fourth pillar of Indian Democracy: Freedom of the Press

This article has been written by Anubhav Garg.

Table of Contents

Introduction

In the world’s largest democracy, the freedom of speech and expression is the most crucial fundamental right availed to the citizens by the constitution. The media is considered as the fourth pillar of democracy and it plays a vital role in a country’s social, political, economical and international affairs. Thus, it goes without saying that free press is a sine qua non for a democracy to survive and thrive and preserve the ethos of good and transparent governance.

In the past, India has witnessed the rise of political parties (Modi government), falling of the governments (Rajiv Gandhi’s government), crashing of the economy(2008 crisis) and stock markets getting skyrocketed (bullish Indian stock market after US-China Trade war ), all based on the information broadcasted regarding them by the media. A country’s international reputation and the global impression are largely influenced by the kind of news which prevails about that particular country in the international press.

What is Freedom of Press?

Freedom of the press refers to the minimal interference of the state in the operation of press on any form of communication including, print (newspapers, magazines, journals, reports); audio (radios, podcasts); video (news channels, OTT platforms like YouTube) and over other electronic mediums like news apps, social media feeds, etc.

The liberty of the press in the words of Lord Mansfield is, “consists of printing without any license subject to the consequences of law”. Therefore, we can conclude that freedom of the press refers to having the freedom to express what one pleases without any prior permission from law.

Why Freedom of the Press?

As per Indian Newspapers v Union of India , the objective of the press is to supplement the public interest by printing the facts and opinions without which the citizens of the country cannot make well informed rational judgments. Freedom of the press is in the crux of social and political inter-course. It is the paramount duty of the judiciary to prop the freedom of the press and refute all laws and executive actions that interfere with it as opposed to the constitutional provisions.

Press is a medium of availing knowledge and spreading the vital information of events, developments, incidents of national interest to the whole nation and thus free and fair operation of the press makes the backbone of civil society which is capable of critical and independent thinking and forms its opinion about the country and the government after scrutinizing the facts of the situation wisely.

Article 19 and Freedom of Press

Freedom of the press is implicit under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, which provides for the freedom of speech and expression under Part III (fundamental rights). It does not explicitly provide the term “freedom of the press” anywhere but it becomes quite clear from this Constituent assembly debate when Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar replies to a question of “Article 19 not including ‘freedom of the press’” saying that the press is just another method of quoting an individual citizen and when anyone chooses to write in a newspaper, they are merely exercising their right of expression and thus, there is absolutely no need to separately mentions the freedom of the press.

Scope of Freedom of Press under Article 19(1)(a)

Freedom to spread information .

Without this liberty, freedom of the press is nugatory. Though this right is also implicit in the freedom of expression, Romesh Thapar v State of Madras makes it explicit. The mainline of difference between the freedom of the press and freedom of expression for an individual is that an individual can’t communicate to masses on his own, but a press can by means of its publications on various mediums like print, broadcasts, electronic, etc. Thus, freedom to spread information is an intrinsic part of freedom of the press.

Freedom to criticize

The press, just like individuals have the liberty to criticize the government, its officials, its policies, its actions, its laws, its statements, etc. However, the press cannot take abuse this right and cannot provoke the public against the government or cannot abet riots, rebels, or mutiny or insecurity of the state or the government.

Freedom to receive the information

Again, the heart of the liberty to press. If the press is not equipped with the information, it cannot empower the public with the knowledge and thus, the right of expression will become futile because there will be no access to information on whose basis anything can be expressed.

Freedom to conduct interview

This right is necessary to bring in first hand knowledge from the experts on the particulars subjects and to enlighten the society at large. Though this right is not absolute, there are three caveats to it as follow:

- Interview will only take place on the consent of the interviewee;

- Interview shall stop when the interviewee wants to it to be;

- Interviewer can’t force interviewee to answer any question against his/her will.

Freedom to report court proceedings

In the words of Jeremy Bentham, “the soul of justice is publicity”. In Sahara India Real Estate Corpn ltd v SEBI , SC held that it is the right of the media to report the judicial proceedings. In Saroj Iyer v Maharashtra Medical (Council) of Indian Medicine, SC held that the right to print faithful reports of the legal proceedings witnessed is available even if it is against quasi-judicial tribunals.

Freedom to attend and report legislative proceedings