Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

Published on November 2, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on May 31, 2023.

A research problem is a specific issue or gap in existing knowledge that you aim to address in your research. You may choose to look for practical problems aimed at contributing to change, or theoretical problems aimed at expanding knowledge.

Some research will do both of these things, but usually the research problem focuses on one or the other. The type of research problem you choose depends on your broad topic of interest and the type of research you think will fit best.

This article helps you identify and refine a research problem. When writing your research proposal or introduction , formulate it as a problem statement and/or research questions .

Table of contents

Why is the research problem important, step 1: identify a broad problem area, step 2: learn more about the problem, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research problems.

Having an interesting topic isn’t a strong enough basis for academic research. Without a well-defined research problem, you are likely to end up with an unfocused and unmanageable project.

You might end up repeating what other people have already said, trying to say too much, or doing research without a clear purpose and justification. You need a clear problem in order to do research that contributes new and relevant insights.

Whether you’re planning your thesis , starting a research paper , or writing a research proposal , the research problem is the first step towards knowing exactly what you’ll do and why.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you read about your topic, look for under-explored aspects or areas of concern, conflict, or controversy. Your goal is to find a gap that your research project can fill.

Practical research problems

If you are doing practical research, you can identify a problem by reading reports, following up on previous research, or talking to people who work in the relevant field or organization. You might look for:

- Issues with performance or efficiency

- Processes that could be improved

- Areas of concern among practitioners

- Difficulties faced by specific groups of people

Examples of practical research problems

Voter turnout in New England has been decreasing, in contrast to the rest of the country.

The HR department of a local chain of restaurants has a high staff turnover rate.

A non-profit organization faces a funding gap that means some of its programs will have to be cut.

Theoretical research problems

If you are doing theoretical research, you can identify a research problem by reading existing research, theory, and debates on your topic to find a gap in what is currently known about it. You might look for:

- A phenomenon or context that has not been closely studied

- A contradiction between two or more perspectives

- A situation or relationship that is not well understood

- A troubling question that has yet to be resolved

Examples of theoretical research problems

The effects of long-term Vitamin D deficiency on cardiovascular health are not well understood.

The relationship between gender, race, and income inequality has yet to be closely studied in the context of the millennial gig economy.

Historians of Scottish nationalism disagree about the role of the British Empire in the development of Scotland’s national identity.

Next, you have to find out what is already known about the problem, and pinpoint the exact aspect that your research will address.

Context and background

- Who does the problem affect?

- Is it a newly-discovered problem, or a well-established one?

- What research has already been done?

- What, if any, solutions have been proposed?

- What are the current debates about the problem? What is missing from these debates?

Specificity and relevance

- What particular place, time, and/or group of people will you focus on?

- What aspects will you not be able to tackle?

- What will the consequences be if the problem is not resolved?

Example of a specific research problem

A local non-profit organization focused on alleviating food insecurity has always fundraised from its existing support base. It lacks understanding of how best to target potential new donors. To be able to continue its work, the organization requires research into more effective fundraising strategies.

Once you have narrowed down your research problem, the next step is to formulate a problem statement , as well as your research questions or hypotheses .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them.

In general, they should be:

- Focused and researchable

- Answerable using credible sources

- Complex and arguable

- Feasible and specific

- Relevant and original

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, May 31). How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 14, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-problem/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a strong hypothesis | steps & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write a Statement of the Problem in Research

Table of Contents

The problem statement is a foundation of academic research writing , providing a precise representation of an existing gap or issue in a particular field of study.

Crafting a sharp and focused problem statement lays the groundwork for your research project.

- It highlights the research's significance .

- Emphasizes its potential to influence the broader academic community.

- Represents the initial step for you to make a meaningful contribution to your discipline.

Therefore, in this article, we will discuss what is a statement of the problem in research and how to craft a compelling research problem statement.

What is a research problem statement?

A research problem statement is a concise, clear, and specific articulation of a gap in current knowledge that your research aims to bridge. It not only sets forth the scope and direction of your research but also establishes its relevance and significance.

Your problem statement in your research paper aims to:

- Define the gap : Clearly identify and articulate a specific gap or issue in the existing knowledge.

- Provide direction : Serve as a roadmap, guiding the course of your research and ensuring you remain focused.

- Establish relevance : Highlight the importance and significance of the problem in the context of your field or the broader world.

- Guide inquiry : Formulate the research questions or hypotheses you'll explore.

- Communicate intent : Succinctly convey the core purpose of your research to stakeholders, peers, and any audience.

- Set boundaries : Clearly define the scope of your research to ensure it's focused and achievable.

When should you write a problem statement in research?

Initiate your research by crafting a clear problem statement. This should be done before any data collection or analysis, serving as a foundational anchor that clearly identifies the specific issue you aim to address.

By establishing this early on, you shape the direction of your research, ensuring it targets a genuine knowledge gap.

Furthermore, an effective and a concise statement of the problem in research attracts collaborators, funders, and supporters, resonating with its clarity and purpose. Remember, as your research unfolds, the statement might evolve, reflecting new insights and staying pertinent.

But how do you distinguish between a well-crafted problem statement and one that falls short?

Effective vs. ineffective research problem statements

Imagine a scenario where medical researchers aim to tackle a new strain of virus. Their effective problem statement wouldn't merely state the existence of the virus. Instead, it would delve into the specifics — the regions most affected, the demographics most vulnerable, and the current limitations in medical interventions.

Whereas an ineffective research problem statement is vague, overly broad, or ambiguous, failing to provide a clear direction for the research. It may not be rooted in existing literature, might lack clarity on its significance, or could be framed in a way that makes the research objectives unachievable or irrelevant.

To understand it better, let's consider the topic of “Remote work and employee productivity.”

Effective problem statement

“Over the past decade, there has been a 70% increase in organizations adopting remote work policies. While some studies suggest remote work enhances employee productivity, others indicate potential declines due to distractions at home.

However, there’s a lack of comprehensive research examining the specific factors in a remote environment that influence productivity. This study aims to identify and analyze these factors, providing organizations with actionable insights to optimize remote work policies.”

Why is this statement of a problem in research effective?

- Specificity : The statement provides a clear percentage to highlight the rise in remote work.

- Context : It acknowledges existing research and the conflicting findings.

- Clear gap identification : It points out the lack of comprehensive research on specific factors affecting productivity in remote work.

- Purpose : The statement concludes with a clear aim for the research.

Ineffective problem statement

"People are working from home a lot now, especially since there are so many internet tools. Some say it's good; others say it's not that great. This research will just look into the whole work-from-home thing and see what's up."

Why is this statement of a problem in research ineffective?

- Informal language : Phrases like "what's up" and "the whole work-from-home thing" are not suitable for academic writing.

- Vagueness : The statement doesn't provide any specific data or context about the rise of remote work.

- Lack of clear focus : It's unclear what aspect of remote work the research will address.

- Ambiguous purpose : The statement doesn't specify the research's objectives or expected outcomes.

After gaining an understanding of what an effective research problem statement looks like, let's dive deeper into how to write one.

How to write a problem statement in research?

Drafting your research problem statement at the onset of your research journey ensures that your research remains anchored. That means by defining and articulating the main issue or challenge you intend to address at the very beginning of your research process; you provide a clear focus and direction for the entire study.

Here's a detailed guide to how you can write an effective statement of the problem in research.

Identify the research area : Before addressing a specific problem, you need to know the broader domain or field of your study. This helps in contextualizing your research and ensuring it aligns with existing academic disciplines.

Example: If you're curious about the effects of digital technology on human behavior, your broader research area might be Digital Sociology or Media Studies.

Conduct preliminary literature review : Familiarize yourself with existing research related to your topic. This will help you understand what's already known and, more importantly, identify gaps or unresolved questions in the existing knowledge. This step also ensures you're advancing upon existing work rather than replicating it.

Example: Upon reviewing literature on digital technology and behavior, you find many studies on social media's impact on youth but fewer on its effects on the elderly.

Read how to conduct an effective literature review .

Define the specific problem : After thoroughly reviewing the literature, pinpoint a particular issue that your research will address. Ensure that this chosen issue is not only of substantial importance in its field but also realistically approachable given your resources and expertise. To define it precisely, you might consider:

- Highlighting discrepancies or contradictions in existing literature.

- Emphasizing the real-world implications of this gap.

- Assessing the feasibility of exploring this issue within your means and timeframe.

Example: You decide to investigate how digital technology, especially social media, affects the mental well-being of the elderly, given the limited research in this area.

Articulate clearly and concisely : Your problem statement should be straightforward and devoid of jargon. It needs to convey the essence of your research issue in a manner that's understandable to both experts and non-experts.

Example: " The impact of social media on the mental well-being of elderly individuals remains underexplored, despite the growing adoption of digital technology in this age group. "

Highlight the significance : Explain why your chosen research problem matters. This could be due to its real-world implications, its potential to fill a knowledge gap or its relevance to current events or trends.

Example: As the elderly population grows and becomes more digitally connected, understanding the psychological effects of social media on this demographic could inform digital literacy programs and mental health interventions.

Ensure feasibility : Your research problem should be something you can realistically study, given your resources, timeframe, and expertise. It's essential to ensure that you can gather data, conduct experiments, or access necessary materials or participants.

Example: You plan to survey elderly individuals in local community centers about their social media usage and perceived mental well-being, ensuring you have the means to reach this demographic.

Seek feedback : Discuss your preliminary problem statement with peers, mentors, or experts in the field. They can provide insights, point out potential pitfalls, or suggest refinements.

Example: After discussing with a gerontologist, you decide to also consider the role of digital training in moderating the effects of social media on the elderly.

Refine and Revise : Based on feedback and further reflection, revise and improve your problem statement. This iterative process ensures clarity, relevance, and precision.

Example: Your refined statement reads: Despite the increasing digital connectivity of the elderly, the effects of social media on their mental well-being, especially in the context of digital training, remain underexplored.

By following these detailed steps, you can craft a research problem statement that is both compelling and academically rigorous.

Having explored the details of crafting a research problem statement, it's crucial to distinguish it from another fundamental element in academic research: the thesis statement.

Difference between a thesis statement and a problem statement

While both terms are central to research, a thesis statement presents your primary claim or argument, whereas a problem statement describes the specific issue your research aims to address.

Think of the thesis statement as the conclusion you're driving towards, while the problem statement identifies a specific gap in current knowledge.

For instance, a problem statement might highlight the rising mental health issues among teenagers, while the thesis statement could propose that increased screen time is a significant contributor.

Refer to the comparison table between what is a thesis and a problem statement in the research below:

Aspect | Thesis Statement | Problem Statement |

Definition | A concise statement that presents the main claim or argument of the research | A clear articulation of a specific issue or gap in knowledge that the research aims to address |

Purpose | To provide readers with the primary focus or argument of the research and what it aims to demonstrate | To highlight a particular issue or gap that the research seeks to address |

Placement | Found in the introduction of a thesis or dissertation, usually within the first 1-2 pages, indicating the central argument or claim the entire work | Positioned early in research papers or proposals, it sets the context by highlighting the issue the research will address, guiding subsequent questions and methodologies |

Nature of statement | Assertive and argumentative, as it makes a claim that the research will support or refute | Descriptive and explanatory, as it outlines the issue without necessarily proposing a solution or stance |

Derived from | Research findings, data analysis, and interpretation | Preliminary literature review, observed gaps in knowledge, or identified issues in a particular field |

Word count | Typically concise, ranging from 1 sentence to a short paragraph (approximately 25-50 words) | Generally more detailed, ranging from a paragraph to a page (approximately 100-300 words) |

Common mistakes to avoid in writing statement of the problem in research

Mistakes in the research problem statement can lead to a domino effect, causing misalignment in research objectives, wasted resources, and even inconclusive or irrelevant results.

Recognizing and avoiding these pitfalls not only strengthens the foundation of your research but also ensures that your efforts concede impactful insights.

Here's a detailed exploration of frequent subjective, qualitative, quantitative and measurable mistakes and how you can sidestep them.

Being too broad or too narrow

A problem statement that's too broad can lack focus, making it challenging to derive specific research questions or objectives. Conversely, a statement that's too narrow might limit the scope of your research or make it too trivial.

Example of mistake: "Studying the effects of diet on health" is too broad, while "Studying the effects of eating green apples at 3 pm on heart health" is overly narrow.

You can refine the scope based on preliminary research. The correct way to write this problem statement will be "Studying the effects of a high-fiber diet on heart health in adults over 50." This statement is neither too broad nor too narrow, and it provides a clear direction for the research.

Using unnecessary jargon or technical language

While academic writing often involves academic terms, overloading your problem statement with jargon can alienate readers and obscure the actual problem.

Example of Mistake: "Examining the diurnal variations in macronutrient ingestion vis-à-vis metabolic homeostasis."

To ensure it’s not complicated, you can simplify and clarify. "Examining how daily changes in nutrient intake affect metabolic balance" conveys the same idea more accessible.

Not emphasizing the "Why" of the problem

It's not enough to state a problem; you must also convey its significance. Why does this problem matter? What are the implications of not addressing it?

Example of Mistake: "Many students are not engaging with online learning platforms."

You can proceed with the approach of highlighting the significance here. "Many students are not engaging with online learning platforms, leading to decreased academic performance and widening educational disparities."

Circular reasoning and lack of relevance

Your problem statement should be grounded in existing research or observed phenomena. Avoid statements that assume what they set out to prove or lack a clear basis in current knowledge.

Example of Mistake: "We need to study X because not enough research has been done on X."

Instead, try grounding your statement based on already-known facts. "While several studies have explored Y, the specific impact of X remains unclear, necessitating further research."

Being overly ambitious

While it's commendable to aim high, your problem statement should reflect a challenge that's achievable within your means, timeframe, and resources.

Example of Mistake: "This research will solve world hunger."

Here, you need to be realistic and focused. "This research aims to develop sustainable agricultural techniques to increase crop yields in arid regions."

By being mindful of these common mistakes, you can craft a problem statement that is clear, relevant and sets a solid foundation for your research.

Over-reliance on outdated data

Using data that is no longer relevant can mislead the direction of your research. It's essential to ensure that the statistics or findings you reference are current and pertinent to the present scenario.

Example of Mistake: "According to a 1995 study, only 5% of the population uses the internet for daily tasks."

You always cross-check the dates and relevance of the data you're using. For a contemporary study on internet usage, you'd want to reference more recent statistics.

Not specifying the sample size or demographic

A problem statement should be clear about the population or sample size being studied, especially when making generalizations or claims.

Example of Mistake: "People prefer online shopping to in-store shopping."

Here, you would benefit from specifying the demographic or sample size when presenting data to avoid overgeneralization. " In a survey of 1,000 urban residents aged 18-35, 70% expressed a preference for online shopping over in-store shopping. "

Ignoring conflicting data

Cherry-picking data that supports your hypothesis while ignoring conflicting data can lead to a biased problem statement.

Example of Mistake: "Research shows that all students benefit from online learning."

You’ve to ensure a balanced view by considering all relevant data, even if it contradicts your hypothesis. " While many studies highlight the advantages of online learning for students, some research points to challenges such as decreased motivation and lack of face-to-face interaction. "

Making unsubstantiated predictions

Projecting future trends without solid data can weaken the credibility of your problem statement.

Example of Mistake: "The demand for electric cars will increase by 500% in the next year."

Base your predictions on current trends and reliable data sources, avoiding hyperbolic or unsupported claims. " With the current growth rate and recent advancements in battery technology, there's potential for a significant rise in the demand for electric cars. "

Wrapping Up

A well-crafted problem statement ensures that your research is focused, relevant, and contributes meaningfully to the broader academic community.

However, the consequences of an incorrect or poorly constructed problem statement can be severe. It can lead to misdirected research efforts, wasted resources, compromised credibility, and even ethical concerns. Such pitfalls underscore the importance of dedicating time and effort to craft a precise and impactful problem statement.

So, as you start your research journey , remember that a well-defined problem statement is not just a starting point; it guides your entire research journey, ensuring clarity, relevance, and meaningful contributions to your field.

Frequently Asked Questions

A problem statement is a clear, concise and specific articulation of a gap in current knowledge that your research aims to bridge.

The Problem Statement should highlight existing gaps in current knowledge and also the significance of the research. It should also include the research question and purpose of the research.

Clear articulation of the problem and establishing relevance; Working thesis (methods to solve the problem); Purpose and scope of study — are the 3 parts of the problem statement.

While the statement of the problem articulates and delineates a particular research problem, Objectives designates the aims, purpose and strategies to address the particular problem.

Here’s an example — “The study aims to identify and analyze the specific factors that impact employee productivity, providing organizations with actionable insights to optimize remote work policies.”

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Problem? Characteristics, Types, and Examples

A research problem is a gap in existing knowledge, a contradiction in an established theory, or a real-world challenge that a researcher aims to address in their research. It is at the heart of any scientific inquiry, directing the trajectory of an investigation. The statement of a problem orients the reader to the importance of the topic, sets the problem into a particular context, and defines the relevant parameters, providing the framework for reporting the findings. Therein lies the importance of research problem s.

The formulation of well-defined research questions is central to addressing a research problem . A research question is a statement made in a question form to provide focus, clarity, and structure to the research endeavor. This helps the researcher design methodologies, collect data, and analyze results in a systematic and coherent manner. A study may have one or more research questions depending on the nature of the study.

Identifying and addressing a research problem is very important. By starting with a pertinent problem , a scholar can contribute to the accumulation of evidence-based insights, solutions, and scientific progress, thereby advancing the frontier of research. Moreover, the process of formulating research problems and posing pertinent research questions cultivates critical thinking and hones problem-solving skills.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Problem ?

Before you conceive of your project, you need to ask yourself “ What is a research problem ?” A research problem definition can be broadly put forward as the primary statement of a knowledge gap or a fundamental challenge in a field, which forms the foundation for research. Conversely, the findings from a research investigation provide solutions to the problem .

A research problem guides the selection of approaches and methodologies, data collection, and interpretation of results to find answers or solutions. A well-defined problem determines the generation of valuable insights and contributions to the broader intellectual discourse.

Characteristics of a Research Problem

Knowing the characteristics of a research problem is instrumental in formulating a research inquiry; take a look at the five key characteristics below:

Novel : An ideal research problem introduces a fresh perspective, offering something new to the existing body of knowledge. It should contribute original insights and address unresolved matters or essential knowledge.

Significant : A problem should hold significance in terms of its potential impact on theory, practice, policy, or the understanding of a particular phenomenon. It should be relevant to the field of study, addressing a gap in knowledge, a practical concern, or a theoretical dilemma that holds significance.

Feasible: A practical research problem allows for the formulation of hypotheses and the design of research methodologies. A feasible research problem is one that can realistically be investigated given the available resources, time, and expertise. It should not be too broad or too narrow to explore effectively, and should be measurable in terms of its variables and outcomes. It should be amenable to investigation through empirical research methods, such as data collection and analysis, to arrive at meaningful conclusions A practical research problem considers budgetary and time constraints, as well as limitations of the problem . These limitations may arise due to constraints in methodology, resources, or the complexity of the problem.

Clear and specific : A well-defined research problem is clear and specific, leaving no room for ambiguity; it should be easily understandable and precisely articulated. Ensuring specificity in the problem ensures that it is focused, addresses a distinct aspect of the broader topic and is not vague.

Rooted in evidence: A good research problem leans on trustworthy evidence and data, while dismissing unverifiable information. It must also consider ethical guidelines, ensuring the well-being and rights of any individuals or groups involved in the study.

Types of Research Problems

Across fields and disciplines, there are different types of research problems . We can broadly categorize them into three types.

- Theoretical research problems

Theoretical research problems deal with conceptual and intellectual inquiries that may not involve empirical data collection but instead seek to advance our understanding of complex concepts, theories, and phenomena within their respective disciplines. For example, in the social sciences, research problem s may be casuist (relating to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience), difference (comparing or contrasting two or more phenomena), descriptive (aims to describe a situation or state), or relational (investigating characteristics that are related in some way).

Here are some theoretical research problem examples :

- Ethical frameworks that can provide coherent justifications for artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, especially in contexts involving autonomous decision-making and moral agency.

- Determining how mathematical models can elucidate the gradual development of complex traits, such as intricate anatomical structures or elaborate behaviors, through successive generations.

- Applied research problems

Applied or practical research problems focus on addressing real-world challenges and generating practical solutions to improve various aspects of society, technology, health, and the environment.

Here are some applied research problem examples :

- Studying the use of precision agriculture techniques to optimize crop yield and minimize resource waste.

- Designing a more energy-efficient and sustainable transportation system for a city to reduce carbon emissions.

- Action research problems

Action research problems aim to create positive change within specific contexts by involving stakeholders, implementing interventions, and evaluating outcomes in a collaborative manner.

Here are some action research problem examples :

- Partnering with healthcare professionals to identify barriers to patient adherence to medication regimens and devising interventions to address them.

- Collaborating with a nonprofit organization to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs aimed at providing job training for underserved populations.

These different types of research problems may give you some ideas when you plan on developing your own.

How to Define a Research Problem

You might now ask “ How to define a research problem ?” These are the general steps to follow:

- Look for a broad problem area: Identify under-explored aspects or areas of concern, or a controversy in your topic of interest. Evaluate the significance of addressing the problem in terms of its potential contribution to the field, practical applications, or theoretical insights.

- Learn more about the problem: Read the literature, starting from historical aspects to the current status and latest updates. Rely on reputable evidence and data. Be sure to consult researchers who work in the relevant field, mentors, and peers. Do not ignore the gray literature on the subject.

- Identify the relevant variables and how they are related: Consider which variables are most important to the study and will help answer the research question. Once this is done, you will need to determine the relationships between these variables and how these relationships affect the research problem .

- Think of practical aspects : Deliberate on ways that your study can be practical and feasible in terms of time and resources. Discuss practical aspects with researchers in the field and be open to revising the problem based on feedback. Refine the scope of the research problem to make it manageable and specific; consider the resources available, time constraints, and feasibility.

- Formulate the problem statement: Craft a concise problem statement that outlines the specific issue, its relevance, and why it needs further investigation.

- Stick to plans, but be flexible: When defining the problem , plan ahead but adhere to your budget and timeline. At the same time, consider all possibilities and ensure that the problem and question can be modified if needed.

Key Takeaways

- A research problem concerns an area of interest, a situation necessitating improvement, an obstacle requiring eradication, or a challenge in theory or practical applications.

- The importance of research problem is that it guides the research and helps advance human understanding and the development of practical solutions.

- Research problem definition begins with identifying a broad problem area, followed by learning more about the problem, identifying the variables and how they are related, considering practical aspects, and finally developing the problem statement.

- Different types of research problems include theoretical, applied, and action research problems , and these depend on the discipline and nature of the study.

- An ideal problem is original, important, feasible, specific, and based on evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it important to define a research problem?

Identifying potential issues and gaps as research problems is important for choosing a relevant topic and for determining a well-defined course of one’s research. Pinpointing a problem and formulating research questions can help researchers build their critical thinking, curiosity, and problem-solving abilities.

How do I identify a research problem?

Identifying a research problem involves recognizing gaps in existing knowledge, exploring areas of uncertainty, and assessing the significance of addressing these gaps within a specific field of study. This process often involves thorough literature review, discussions with experts, and considering practical implications.

Can a research problem change during the research process?

Yes, a research problem can change during the research process. During the course of an investigation a researcher might discover new perspectives, complexities, or insights that prompt a reevaluation of the initial problem. The scope of the problem, unforeseen or unexpected issues, or other limitations might prompt some tweaks. You should be able to adjust the problem to ensure that the study remains relevant and aligned with the evolving understanding of the subject matter.

How does a research problem relate to research questions or hypotheses?

A research problem sets the stage for the study. Next, research questions refine the direction of investigation by breaking down the broader research problem into manageable components. Research questions are formulated based on the problem , guiding the investigation’s scope and objectives. The hypothesis provides a testable statement to validate or refute within the research process. All three elements are interconnected and work together to guide the research.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What are Experimental Groups in Research

What is IMRaD Format in Research?

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE: A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Aug 13, 2024 12:57 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component definition and model

- October 2015

- Thesis for: M.A.

- Advisor: Bernard Charlin, Thierry Karsenti

- Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM)

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Turid Anita Jaastad

- Daniel P. Liston

- J. John Loughran

- Jennifer A. Moon

- S.R. Slings

- Craig C. Lundberg

- Chris Argyris

- Donald A. Schon

- Laura C Dast

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Learning By Thinking: How Reflection Improves Performance

- Learning from direct experience can be more effective if coupled with reflection-that is, the intentional attempt to synthesize, abstract, and articulate the key lessons taught by experience.

- Reflecting on what has been learned makes experience more productive.

- Reflection builds one's confidence in the ability to achieve a goal (i.e., self-efficacy), which in turn translates into higher rates of learning.

Author Abstract

Research on learning has primarily focused on the role of doing (experience) in fostering progress over time. In this paper, we propose that one of the critical components of learning is reflection, or the intentional attempt to synthesize, abstract, and articulate the key lessons taught by experience. Drawing on dual-process theory, we focus on the reflective dimension of the learning process and propose that learning can be augmented by deliberately focusing on thinking about what one has been doing. We test the resulting dual-process learning model experimentally, using a mixed-method design that combines two laboratory experiments with a field experiment conducted in a large business process outsourcing company in India. We find a performance differential when comparing learning-by-doing alone to learning-by-doing coupled with reflection. Further, we hypothesize and find that the effect of reflection on learning is mediated by greater perceived self-efficacy. Together, our results shed light on the role of reflection as a powerful mechanism behind learning.

Paper Information

- Full Working Paper Text

- Working Paper Publication Date: March 2014

- HBS Working Paper Number: 14-093

- Faculty Unit(s): Negotiation, Organizations & Markets ; Technology and Operations Management

- 25 Jun 2024

- Research & Ideas

Rapport: The Hidden Advantage That Women Managers Bring to Teams

- 11 Jun 2024

- In Practice

The Harvard Business School Faculty Summer Reader 2024

How transparency sped innovation in a $13 billion wireless sector.

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- 27 Jun 2016

These Management Practices, Like Certain Technologies, Boost Company Performance

- Performance

- Cognition and Thinking

- Experience and Expertise

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Don’t Underestimate the Power of Self-Reflection

- James R. Bailey

- Scheherazade Rehman

Focus on moments of surprise, failure, and frustration.

Research shows the habit of reflection can separate extraordinary professionals from mediocre ones. But how do you sort which experiences are most significant for your development?

- To answer this questions, the authors asked 442 executives to reflect on which experiences most advanced their professional development and had the most impact on making them better leaders.

- Three distinct themes arose through their analysis: surprise, frustration, and failure. Reflections that involved one or more or of these sentiments proved to be the most valuable in helping the leaders grow.

- Surprise, frustration, and failure. Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. These parts of you are constantly in motion and if you don’t give them time to rest and reflect upon what you learned from them, you will surely fatigue.

Empathy, communication, adaptability, emotional intelligence, compassion. These are all skills you need to thrive in the workplace and become a great leader. Time and again, we even hear that these capabilities are the key to making yourself indispensable — not just now but far into the future. Soft skills, after all, are what make us human, and as far as we know, can’t be performed well by technologies like artificial intelligence.

- James R. Bailey is professor and Hochberg Fellow of Leadership at George Washington University. The author of five books and more than 50 academic papers, he is a frequent contributor to the Harvard Business Review, The Hill, Fortune, Forbes, and Fast Company and appears on many national television and radio programs.

- Scheherazade Rehman is professor and Dean’s Professorial Fellow of International Finance. She is director of the European Union Research Center and former Director of World ExecMBA with Cybersecurity, has appeared in front of the U.S. House and Senate, and been a guest numerous times onPBS Newshour, the Colbert Report, BBC World News, CNBC, Voice of America, and C-Span.

Partner Center

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system.

This post outlines the definition of action research, its stages, and some examples.

Content Index

What is action research?

Stages of action research, the steps to conducting action research, examples of action research, advantages and disadvantages of action research.

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research, it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation. This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

Review existing knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design.

Plan the research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools, and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

Collect data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups. Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

Analyze the data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

Reflect on the findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

Develop an action plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

Implement the action plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

Evaluate and monitor progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

Reflect and iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

This post discusses how action research generates knowledge, its steps, and real-life examples. It is very applicable to the field of research and has a high level of relevance. We can only state that the purpose of this research is to comprehend an issue and find a solution to it.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Insight Hub if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

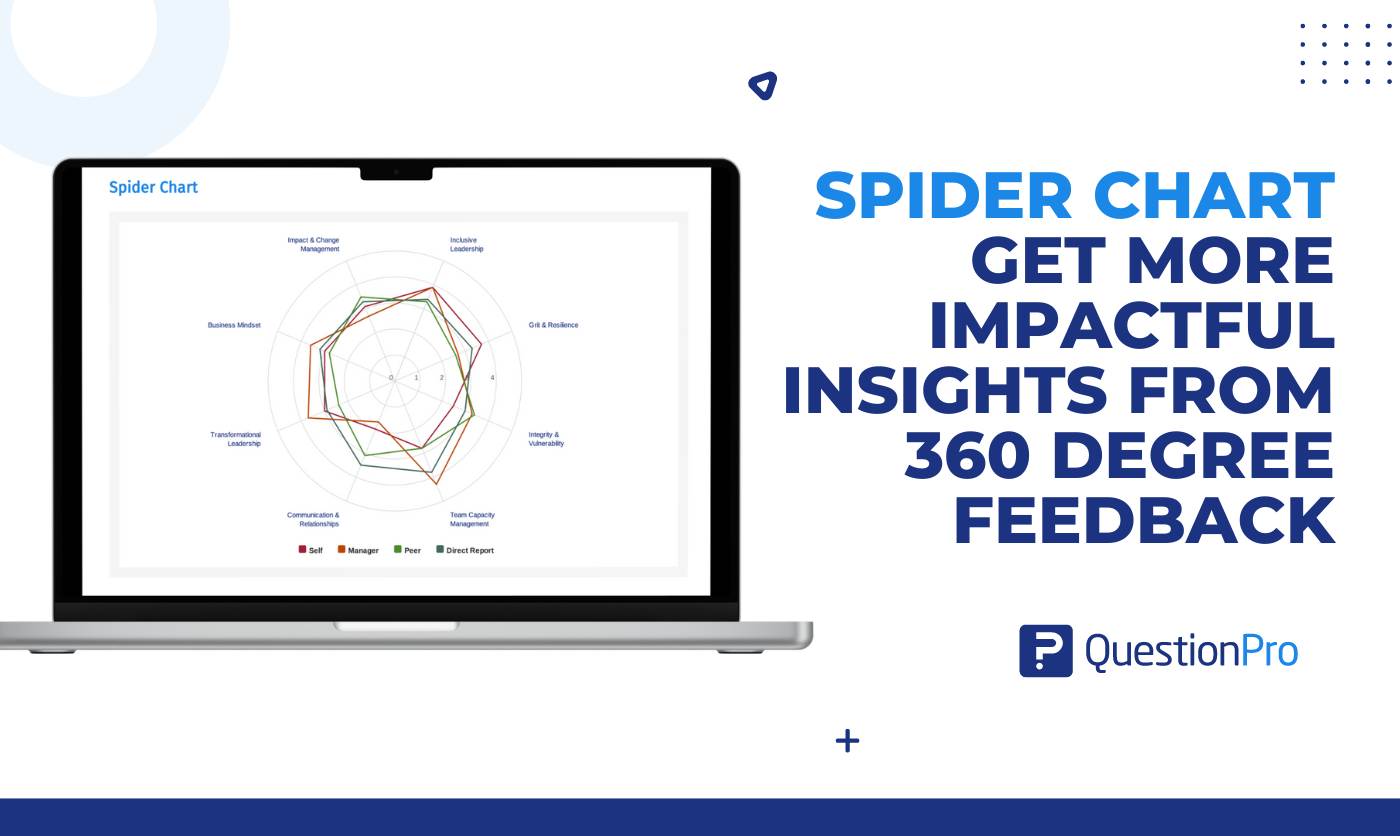

360 Degree Feedback Spider Chart is Back!

Aug 14, 2024

Jotform vs Wufoo: Comparison of Features and Prices

Aug 13, 2024

Product or Service: Which is More Important? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Life@QuestionPro: Thomas Maiwald-Immer’s Experience

Aug 9, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score