- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Basic Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

Case study methodology offers researchers an exciting opportunity to explore intricate phenomena within specific contexts using a wide range of data sources and collection methods. It is highly pertinent in health and social sciences, environmental studies, social work, education, and business studies. Its diverse applications, such as advancing theory, program evaluation, and intervention development, make it an invaluable tool for driving meaningful research and fostering positive change.[ 1]

Table of Contents

What is a Case Study?

A case study method involves a detailed examination of a single subject, such as an individual, group, organization, event, or community, to explore and understand complex issues in real-life contexts. By focusing on one specific case, researchers can gain a deep understanding of the factors and dynamics at play, understanding their complex relationships, which might be missed in broader, more quantitative studies.

When to do a Case Study?

A case study design is useful when you want to explore a phenomenon in-depth and in its natural context. Here are some examples of when to use a case study :[ 2]

- Exploratory Research: When you want to explore a new topic or phenomenon, a case study can help you understand the subject deeply. For example , a researcher studying a newly discovered plant species might use a case study to document its characteristics and behavior.

- Descriptive Research: If you want to describe a complex phenomenon or process, a case study can provide a detailed and comprehensive description. For instance, a case study design could describe the experiences of a group of individuals living with a rare disease.

- Explanatory Research: When you want to understand why a particular phenomenon occurs, a case study can help you identify causal relationships. A case study design could investigate the reasons behind the success or failure of a particular business strategy.

- Theory Building: Case studies can also be used to develop or refine theories. By systematically analyzing a series of cases, researchers can identify patterns and relationships that can contribute to developing new theories or refining existing ones.

- Critical Instance: Sometimes, a single case can be used to study a rare or unusual phenomenon, but it is important for theoretical or practical reasons. For example , the case of Phineas Gage, a man who survived a severe brain injury, has been widely studied to understand the relationship between the brain and behavior.

- Comparative Analysis: Case studies can also compare different cases or contexts. A case study example involves comparing the implementation of a particular policy in different countries to understand its effectiveness and identifying best practices.

How to Create a Case Study – Step by Step

Step 1: select a case .

Careful case selection ensures relevance, insight, and meaningful contribution to existing knowledge in your field. Here’s how you can choose a case study design :[ 3]

- Define Your Objectives: Clarify the purpose of your case study and what you hope to achieve. Do you want to provide new insights, challenge existing theories, propose solutions to a problem, or explore new research directions?

- Consider Unusual or Outlying Cases: Focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases that can provide unique insights.

- Choose a Representative Case: Alternatively, select a common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

- Avoid Bias: Ensure your selection process is unbiased using random or criteria-based selection.

- Be Clear and Specific: Clearly define the boundaries of your study design , including the scope, timeframe, and key stakeholders.

- Ethical Considerations: Consider ethical issues, such as confidentiality and informed consent.

Step 2: Build a Theoretical Framework

To ensure your case study has a solid academic foundation, it’s important to build a theoretical framework:

- Conduct a Literature Review: Identify key concepts and theories relevant to your case study .

- Establish Connections with Theory: Connect your case study with existing theories in the field.

- Guide Your Analysis and Interpretation: Use your theoretical framework to guide your analysis, ensuring your findings are grounded in established theories and concepts.

Step 3: Collect Your Data

To conduct a comprehensive case study , you can use various research methods. These include interviews, observations, primary and secondary sources analysis, surveys, and a mixed methods approach. The aim is to gather rich and diverse data to enable a detailed analysis of your case study .

Step 4: Describe and Analyze the Case

How you report your findings will depend on the type of research you’re conducting. Here are two approaches:

- Structured Approach: Follows a scientific paper format, making it easier for readers to follow your argument.

- Narrative Approach: A more exploratory style aiming to analyze meanings and implications.

Regardless of the approach you choose, it’s important to include the following elements in your case study :

- Contextual Details: Provide background information about the case, including relevant historical, cultural, and social factors that may have influenced the outcome.

- Literature and Theory: Connect your case study to existing literature and theory in the field. Discuss how your findings contribute to or challenge existing knowledge.

- Wider Patterns or Debates: Consider how your case study fits into wider patterns or debates within the field. Discuss any implications your findings may have for future research or practice.

What Are the Benefits of a Case Study

Case studies offer a range of benefits , making them a powerful tool in research.

1. In-Depth Analysis

- Comprehensive Understanding: Case studies allow researchers to thoroughly explore a subject, understanding the complexities and nuances involved.

- Rich Data: They offer rich qualitative and sometimes quantitative data, capturing the intricacies of real-life contexts.

2. Contextual Insight

- Real-World Application: Case studies provide insights into real-world applications, making the findings highly relevant and practical.

- Context-Specific: They highlight how various factors interact within a specific context, offering a detailed picture of the situation.

3. Flexibility

- Methodological Diversity: Case studies can use various data collection methods, including interviews, observations, document analysis, and surveys.

- Adaptability: Researchers can adapt the case study approach to fit the specific needs and circumstances of the research.

4. Practical Solutions

- Actionable Insights: The detailed findings from case studies can inform practical solutions and recommendations for practitioners and policymakers.

- Problem-Solving: They help understand the root causes of problems and devise effective strategies to address them.

5. Unique Cases

- Rare Phenomena: Case studies are particularly valuable for studying rare or unique cases that other research methods may not capture.

- Detailed Documentation: They document and preserve detailed information about specific instances that might otherwise be overlooked.

What Are the Limitations of a Case Study

While case studies offer valuable insights and a detailed understanding of complex issues, they have several limitations .

1. Limited Generalizability

- Specific Context: Case studies often focus on a single case or a small number of cases, which may limit the generalization of findings to broader populations or different contexts.

- Unique Situations: The unique characteristics of the case may not be representative of other situations, reducing the applicability of the results.

2. Subjectivity

- Researcher Bias: The researcher’s perspectives and interpretations can influence the analysis and conclusions, potentially introducing bias.

- Participant Bias: Participants’ responses and behaviors may be influenced by their awareness of being studied, known as the Hawthorne effect.

3. Time-Consuming

- Data Collection and Analysis: Gathering detailed, in-depth data requires significant time and effort, making case studies more time-consuming than other research methods.

- Longitudinal Studies: If the case study observes changes over time, it can become even more prolonged.

4. Resource Intensive

- Financial and Human Resources: Conducting comprehensive case studies may require significant financial investment and human resources, including trained researchers and participant access.

- Access to Data: Accessing relevant and reliable data sources can be challenging, particularly in sensitive or proprietary contexts.

5. Replication Difficulties

- Unique Contexts: A case study’s specific and detailed context makes it difficult to replicate the study exactly, limiting the ability to validate findings through repetition.

- Variability: Differences in contexts, researchers, and methodologies can lead to variations in findings, complicating efforts to achieve consistent results.

By acknowledging and addressing these limitations , researchers can enhance the rigor and reliability of their case study findings.

Key Takeaways

Case studies are valuable in research because they provide an in-depth, contextual analysis of a single subject, event, or organization. They allow researchers to explore complex issues in real-world settings, capturing detailed qualitative and quantitative data. This method is useful for generating insights, developing theories, and offering practical solutions to problems. They are versatile, applicable in diverse fields such as business, education, and health, and can complement other research methods by providing rich, contextual evidence. However, their findings may have limited generalizability due to the focus on a specific case.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is a case study in research?

A case study in research is an impactful tool for gaining a deep understanding of complex issues within their real-life context. It combines various data collection methods and provides rich, detailed insights that can inform theory development and practical applications.

Q: What are the advantages of using case studies in research?

Case studies are a powerful research method, offering advantages such as in-depth analysis, contextual insights, flexibility, rich data, and the ability to handle complex issues. They are particularly valuable for exploring new areas, generating hypotheses, and providing detailed, illustrative examples that can inform theory and practice.

Q: Can case studies be used in quantitative research?

While case studies are predominantly associated with qualitative research, they can effectively incorporate quantitative methods to provide a more comprehensive analysis. A mixed-methods approach leverages qualitative and quantitative research strengths, offering a powerful tool for exploring complex issues in a real-world context. For example , a new medical treatment case study can incorporate quantitative clinical outcomes (e.g., patient recovery rates and dosage levels) along with qualitative patient interviews.

Q: What are the key components of a case study?

A case study typically includes several key components:

- Introductio n, which provides an overview and sets the context by presenting the problem statement and research objectives;

- Literature review , which connects the study to existing theories and prior research;

- Methodology , which details the case study design , data collection methods, and analysis techniques;

- Findings , which present the data and results, including descriptions, patterns, and themes;

- Discussion and conclusion , which interpret the findings, discuss their implications, and offer conclusions, practical applications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Together, these components ensure a comprehensive, systematic, and insightful exploration of the case.

References

- de Vries, K. (2020). Case study methodology. In Critical qualitative health research (pp. 41-52). Routledge.

- Fidel, R. (1984). The case study method: A case study. Library and Information Science Research , 6 (3), 273-288.

- Thomas, G. (2021). How to do your case study. How to do your case study , 1-320.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What is Correlational Research: Definition, Types, and Examples

What is JSTOR? How to Use JSTOR for Research?

- User Experience (UX) Testing User Interface (UI) Testing Ecommerce Testing Remote Usability Testing About the company ' data-html="true"> Why Trymata

- Usability testing

Run remote usability tests on any digital product to deep dive into your key user flows

- Product analytics

Learn how users are behaving on your website in real time and uncover points of frustration

- Research repository

A tool for collaborative analysis of qualitative data and for building your research repository and database.

See an example

- Trymata Blog

How-to articles, expert tips, and the latest news in user testing & user experience

- Knowledge Hub

Detailed explainers of Trymata’s features & plans, and UX research terms & topics

Visit Knowledge Hub

- Plans & Pricing

Get paid to test

- User Experience (UX) testing

- User Interface (UI) testing

- Ecommerce testing

- Remote usability testing

- Plans & Pricing

- Customer Stories

How do you want to use Trymata?

Conduct user testing, desktop usability video.

You’re on a business trip in Oakland, CA. You've been working late in downtown and now you're looking for a place nearby to grab a late dinner. You decided to check Zomato to try and find somewhere to eat. (Don't begin searching yet).

- Look around on the home page. Does anything seem interesting to you?

- How would you go about finding a place to eat near you in Downtown Oakland? You want something kind of quick, open late, not too expensive, and with a good rating.

- What do the reviews say about the restaurant you've chosen?

- What was the most important factor for you in choosing this spot?

- You're currently close to the 19th St Bart station, and it's 9PM. How would you get to this restaurant? Do you think you'll be able to make it before closing time?

- Your friend recommended you to check out a place called Belly while you're in Oakland. Try to find where it is, when it's open, and what kind of food options they have.

- Now go to any restaurant's page and try to leave a review (don't actually submit it).

What was the worst thing about your experience?

It was hard to find the bart station. The collections not being able to be sorted was a bit of a bummer

What other aspects of the experience could be improved?

Feedback from the owners would be nice

What did you like about the website?

The flow was good, lots of bright photos

What other comments do you have for the owner of the website?

I like that you can sort by what you are looking for and i like the idea of collections

You're going on a vacation to Italy next month, and you want to learn some basic Italian for getting around while there. You decided to try Duolingo.

- Please begin by downloading the app to your device.

- Choose Italian and get started with the first lesson (stop once you reach the first question).

- Now go all the way through the rest of the first lesson, describing your thoughts as you go.

- Get your profile set up, then view your account page. What information and options are there? Do you feel that these are useful? Why or why not?

- After a week in Italy, you're going to spend a few days in Austria. How would you take German lessons on Duolingo?

- What other languages does the app offer? Do any of them interest you?

I felt like there could have been a little more of an instructional component to the lesson.

It would be cool if there were some feature that could allow two learners studying the same language to take lessons together. I imagine that their screens would be synced and they could go through lessons together and chat along the way.

Overall, the app was very intuitive to use and visually appealing. I also liked the option to connect with others.

Overall, the app seemed very helpful and easy to use. I feel like it makes learning a new language fun and almost like a game. It would be nice, however, if it contained more of an instructional portion.

All accounts, tests, and data have been migrated to our new & improved system!

Use the same email and password to log in:

Legacy login: Our legacy system is still available in view-only mode, login here >

What’s the new system about? Read more about our transition & what it-->

What is a Case Study? Definition, Research Methods, Sampling and Examples

Conduct End-to-End User Testing & Research

What is a Case Study?

A case study is defined as an in-depth analysis of a particular subject, often a real-world situation, individual, group, or organization.

It is a research method that involves the comprehensive examination of a specific instance to gain a better understanding of its complexities, dynamics, and context.

Case studies are commonly used in various fields such as business, psychology, medicine, and education to explore and illustrate phenomena, theories, or practical applications.

In a typical case study, researchers collect and analyze a rich array of qualitative and/or quantitative data, including interviews, observations, documents, and other relevant sources. The goal is to provide a nuanced and holistic perspective on the subject under investigation.

The information gathered here is used to generate insights, draw conclusions, and often to inform broader theories or practices within the respective field.

Case studies offer a valuable method for researchers to explore real-world phenomena in their natural settings, providing an opportunity to delve deeply into the intricacies of a particular case. They are particularly useful when studying complex, multifaceted situations where various factors interact.

Additionally, case studies can be instrumental in generating hypotheses, testing theories, and offering practical insights that can be applied to similar situations. Overall, the comprehensive nature of case studies makes them a powerful tool for gaining a thorough understanding of specific instances within the broader context of academic and professional inquiry.

Key Characteristics of Case Study

Case studies are characterized by several key features that distinguish them from other research methods. Here are some essential characteristics of case studies:

- In-depth Exploration: Case studies involve a thorough and detailed examination of a specific case or instance. Researchers aim to explore the complexities and nuances of the subject under investigation, often using multiple data sources and methods to gather comprehensive information.

- Contextual Analysis: Case studies emphasize the importance of understanding the context in which the case unfolds. Researchers seek to examine the unique circumstances, background, and environmental factors that contribute to the dynamics of the case. Contextual analysis is crucial for drawing meaningful conclusions and generalizing findings to similar situations.

- Holistic Perspective: Rather than focusing on isolated variables, case studies take a holistic approach to studying a phenomenon. Researchers consider a wide range of factors and their interrelationships, aiming to capture the richness and complexity of the case. This holistic perspective helps in providing a more complete understanding of the subject.

- Qualitative and/or Quantitative Data: Case studies can incorporate both qualitative and quantitative data, depending on the research question and objectives. Qualitative data often include interviews, observations, and document analysis, while quantitative data may involve statistical measures or numerical information. The combination of these data types enhances the depth and validity of the study.

- Longitudinal or Retrospective Design: Case studies can be designed as longitudinal studies, where the researcher follows the case over an extended period, or retrospective studies, where the focus is on examining past events. This temporal dimension allows researchers to capture changes and developments within the case.

- Unique and Unpredictable Nature: Each case study is unique, and the findings may not be easily generalized to other situations. The unpredictable nature of real-world cases adds a layer of authenticity to the study, making it an effective method for exploring complex and dynamic phenomena.

- Theory Building or Testing: Case studies can serve different purposes, including theory building or theory testing. In some cases, researchers use case studies to develop new theories or refine existing ones. In others, they may test existing theories by applying them to real-world situations and assessing their explanatory power.

Understanding these key characteristics is essential for researchers and practitioners using case studies as a methodological approach, as it helps guide the design, implementation, and analysis of the study.

Key Components of a Case Study

A well-constructed case study typically consists of several key components that collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under investigation. Here are the key components of a case study:

- Provide an overview of the context and background information relevant to the case. This may include the history, industry, or setting in which the case is situated.

- Clearly state the purpose and objectives of the case study. Define what the study aims to achieve and the questions it seeks to answer.

- Clearly identify the subject of the case study. This could be an individual, a group, an organization, or a specific event.

- Define the boundaries and scope of the case study. Specify what aspects will be included and excluded from the investigation.

- Provide a brief review of relevant theories or concepts that will guide the analysis. This helps place the case study within the broader theoretical context.

- Summarize existing literature related to the subject, highlighting key findings and gaps in knowledge. This establishes the context for the current case study.

- Describe the research design chosen for the case study (e.g., exploratory, explanatory, descriptive). Justify why this design is appropriate for the research objectives.

- Specify the methods used to gather data, whether through interviews, observations, document analysis, surveys, or a combination of these. Detail the procedures followed to ensure data validity and reliability.

- Explain the criteria for selecting the case and any sampling considerations. Discuss why the chosen case is representative or relevant to the research questions.

- Describe how the collected data will be coded and categorized. Discuss the analytical framework or approach used to identify patterns, themes, or trends.

- If multiple data sources or methods are used, explain how they complement each other to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings.

- Present the key findings in a clear and organized manner. Use tables, charts, or quotes from participants to illustrate the results.

- Interpret the results in the context of the research objectives and theoretical framework. Discuss any unexpected findings and their implications.

- Provide a thorough interpretation of the results, connecting them to the research questions and relevant literature.

- Acknowledge the limitations of the study, such as constraints in data collection, sample size, or generalizability.

- Highlight the contributions of the case study to the existing body of knowledge and identify potential avenues for future research.

- Summarize the key findings and their significance in relation to the research objectives.

- Conclude with a concise summary of the case study, its implications, and potential practical applications.

- Provide a complete list of all the sources cited in the case study, following a consistent citation style.

- Include any additional materials or supplementary information, such as interview transcripts, survey instruments, or supporting documents.

By including these key components, a case study becomes a comprehensive and well-rounded exploration of a specific subject, offering valuable insights and contributing to the body of knowledge in the respective field.

Sampling in a Case Study Research

Sampling in case study research involves selecting a subset of cases or individuals from a larger population to study in depth. Unlike quantitative research where random sampling is often employed, case study sampling is typically purposeful and driven by the specific objectives of the study. Here are some key considerations for sampling in case study research:

- Criterion Sampling: Cases are selected based on specific criteria relevant to the research questions. For example, if studying successful business strategies, cases may be selected based on their demonstrated success.

- Maximum Variation Sampling: Cases are chosen to represent a broad range of variations related to key characteristics. This approach helps capture diversity within the sample.

- Selecting Cases with Rich Information: Researchers aim to choose cases that are information-rich and provide insights into the phenomenon under investigation. These cases should offer a depth of detail and variation relevant to the research objectives.

- Single Case vs. Multiple Cases: Decide whether the study will focus on a single case (single-case study) or multiple cases (multiple-case study). The choice depends on the research objectives, the complexity of the phenomenon, and the depth of understanding required.

- Emergent Nature of Sampling: In some case studies, the sampling strategy may evolve as the study progresses. This is known as theoretical sampling, where new cases are selected based on emerging findings and theoretical insights from earlier analysis.

- Data Saturation: Sampling may continue until data saturation is achieved, meaning that collecting additional cases or data does not yield new insights or information. Saturation indicates that the researcher has adequately explored the phenomenon.

- Defining Case Boundaries: Clearly define the boundaries of the case to ensure consistency and avoid ambiguity. Consider what is included and excluded from the case study, and justify these decisions.

- Practical Considerations: Assess the feasibility of accessing the selected cases. Consider factors such as availability, willingness to participate, and the practicality of data collection methods.

- Informed Consent: Obtain informed consent from participants, ensuring that they understand the purpose of the study and the ways in which their information will be used. Protect the confidentiality and anonymity of participants as needed.

- Pilot Testing the Sampling Strategy: Before conducting the full study, consider pilot testing the sampling strategy to identify potential challenges and refine the approach. This can help ensure the effectiveness of the sampling method.

- Transparent Reporting: Clearly document the sampling process in the research methodology section. Provide a rationale for the chosen sampling strategy and discuss any adjustments made during the study.

Sampling in case study research is a critical step that influences the depth and richness of the study’s findings. By carefully selecting cases based on specific criteria and considering the unique characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation, researchers can enhance the relevance and validity of their case study.

Case Study Research Methods With Examples

- Interviews:

- Interviews involve engaging with participants to gather detailed information, opinions, and insights. In a case study, interviews are often semi-structured, allowing flexibility in questioning.

- Example: A case study on workplace culture might involve conducting interviews with employees at different levels to understand their perceptions, experiences, and attitudes.

- Observations:

- Observations entail direct examination and recording of behavior, activities, or events in their natural setting. This method is valuable for understanding behaviors in context.

- Example: A case study investigating customer interactions at a retail store may involve observing and documenting customer behavior, staff interactions, and overall dynamics.

- Document Analysis:

- Document analysis involves reviewing and interpreting written or recorded materials, such as reports, memos, emails, and other relevant documents.

- Example: In a case study on organizational change, researchers may analyze internal documents, such as communication memos or strategic plans, to trace the evolution of the change process.

- Surveys and Questionnaires:

- Surveys and questionnaires collect structured data from a sample of participants. While less common in case studies, they can be used to supplement other methods.

- Example: A case study on the impact of a health intervention might include a survey to gather quantitative data on participants’ health outcomes.

- Focus Groups:

- Focus groups involve a facilitated discussion among a group of participants to explore their perceptions, attitudes, and experiences.

- Example: In a case study on community development, a focus group might be conducted with residents to discuss their views on recent initiatives and their impact.

- Archival Research:

- Archival research involves examining existing records, historical documents, or artifacts to gain insights into a particular phenomenon.

- Example: A case study on the history of a landmark building may involve archival research, exploring construction records, historical photos, and maintenance logs.

- Longitudinal Studies:

- Longitudinal studies involve the collection of data over an extended period to observe changes and developments.

- Example: A case study tracking the career progression of employees in a company may involve longitudinal interviews and document analysis over several years.

- Cross-Case Analysis:

- Cross-case analysis compares and contrasts multiple cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences.

- Example: A comparative case study of different educational institutions may involve analyzing common challenges and successful strategies across various cases.

- Ethnography:

- Ethnography involves immersive, in-depth exploration within a cultural or social setting to understand the behaviors and perspectives of participants.

- Example: A case study using ethnographic methods might involve spending an extended period within a community to understand its social dynamics and cultural practices.

- Experimental Designs (Rare):

- While less common, experimental designs involve manipulating variables to observe their effects. In case studies, this might be applied in specific contexts.

- Example: A case study exploring the impact of a new teaching method might involve implementing the method in one classroom while comparing it to a traditional method in another.

These case study research methods offer a versatile toolkit for researchers to investigate and gain insights into complex phenomena across various disciplines. The choice of methods depends on the research questions, the nature of the case, and the desired depth of understanding.

Best Practices for a Case Study in 2024

Creating a high-quality case study involves adhering to best practices that ensure rigor, relevance, and credibility. Here are some key best practices for conducting and presenting a case study:

- Clearly articulate the purpose and objectives of the case study. Define the research questions or problems you aim to address, ensuring a focused and purposeful approach.

- Choose a case that aligns with the research objectives and provides the depth and richness needed for the study. Consider the uniqueness of the case and its relevance to the research questions.

- Develop a robust research design that aligns with the nature of the case study (single-case or multiple-case) and integrates appropriate research methods. Ensure the chosen design is suitable for exploring the complexities of the phenomenon.

- Use a variety of data sources to enhance the validity and reliability of the study. Combine methods such as interviews, observations, document analysis, and surveys to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Clearly document and describe the procedures for data collection to enhance transparency. Include details on participant selection, sampling strategy, and data collection methods to facilitate replication and evaluation.

- Implement measures to ensure the validity and reliability of the data. Triangulate information from different sources to cross-verify findings and strengthen the credibility of the study.

- Clearly define the boundaries of the case to avoid scope creep and maintain focus. Specify what is included and excluded from the study, providing a clear framework for analysis.

- Include perspectives from various stakeholders within the case to capture a holistic view. This might involve interviewing individuals at different organizational levels, customers, or community members, depending on the context.

- Adhere to ethical principles in research, including obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality, and addressing any potential conflicts of interest.

- Conduct a rigorous analysis of the data, using appropriate analytical techniques. Interpret the findings in the context of the research questions, theoretical framework, and relevant literature.

- Offer detailed and rich descriptions of the case, including the context, key events, and participant perspectives. This helps readers understand the intricacies of the case and supports the generalization of findings.

- Communicate findings in a clear and accessible manner. Avoid jargon and technical language that may hinder understanding. Use visuals, such as charts or graphs, to enhance clarity.

- Seek feedback from colleagues or experts in the field through peer review. This helps ensure the rigor and credibility of the case study and provides valuable insights for improvement.

- Connect the case study findings to existing theories or concepts, contributing to the theoretical understanding of the phenomenon. Discuss practical implications and potential applications in relevant contexts.

- Recognize that case study research is often an iterative process. Be open to revisiting and refining research questions, methods, or analysis as the study progresses. Practice reflexivity by acknowledging and addressing potential biases or preconceptions.

By incorporating these best practices, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their case studies, making valuable contributions to the academic and practical understanding of complex phenomena.

Interested in learning more about the fields of product, research, and design? Search our articles here for helpful information spanning a wide range of topics!

Deceptive Patterns: What are They, How to Identify & Avoid Them?

Customer empathy transforming usability testing, customer activation tips for usability testing success, ux desk research: a practical guide for usability testing.

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

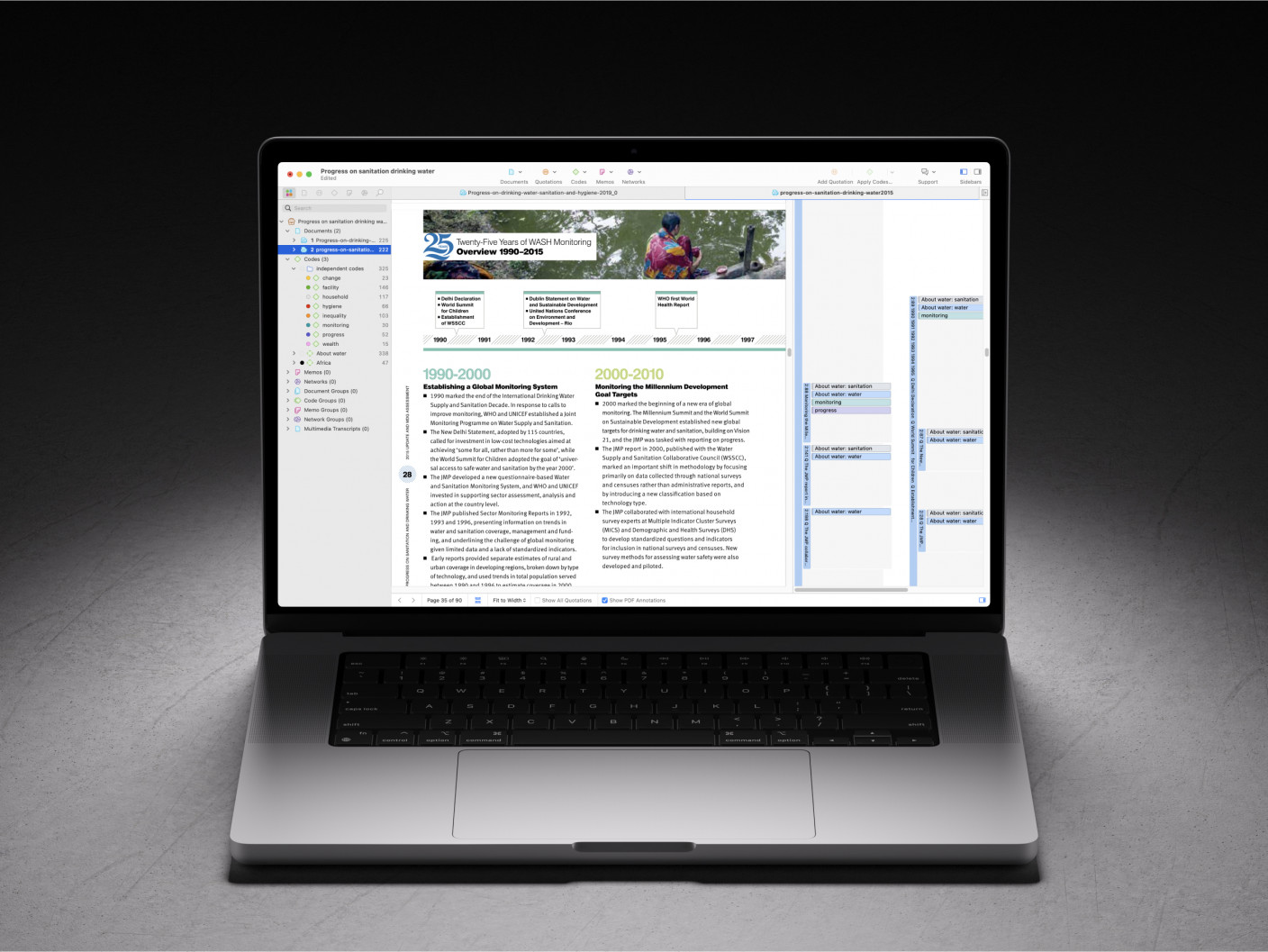

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Seminal Authors