45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Sustainable Development: Samples in 250, 300 and 500 Words

- Updated on

- Nov 18, 2023

On 3rd August 2023, the Indian Government released its Net zero emissions target policy to reduce its carbon footprints. To achieve the sustainable development goals (SDG) , as specified by the UN, India is determined for its long-term low-carbon development strategy. Selfishly pursuing modernization, humans have frequently compromised with the requirements of a more sustainable environment.

As a result, the increased environmental depletion is evident with the prevalence of deforestation, pollution, greenhouse gases, climate change etc. To combat these challenges, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) in 2019. The objective was to improve air quality in 131 cities in 24 States/UTs by engaging multiple stakeholders.

‘Development is not real until and unless it is sustainable development.’ – Ban Ki-Moon

Sustainable Development Goals, also known as SGDs, are a list of 17 goals to build a sustained and better tomorrow. These 17 SDGs are known as the ‘World’s Best Plan’ to eradicate property, tackle climate change, and empower people for global welfare.

This Blog Includes:

What is sustainable development, essay on sustainable development in 250 words, 300 words essay on sustainable development, 500 words essay on sustainable development, what are sdgs, introduction, conclusion of sustainable development essay, importance of sustainable development, examples of sustainable development.

As the term simply explains, Sustainable Development aims to bring a balance between meeting the requirements of what the present demands while not overlooking the needs of future generations. It acknowledges nature’s requirements along with the human’s aim to work towards the development of different aspects of the world. It aims to efficiently utilise resources while also meticulously planning the accomplishment of immediate as well as long-term goals for human beings, the planet as well and future generations. In the present time, the need for Sustainable Development is not only for the survival of mankind but also for its future protection.

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 250 words:

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 300+ words:

We all remember the historical @BTS_twt speech supporting #Youth2030 initiative to empower young people to use their voices for change. Tomorrow, #BTSARMY 💜 will be in NYC🗽again for the #SDGmoment at #UNGA76 Live 8AM EST welcome back #BTSARMY 👏🏾 pic.twitter.com/pUnBni48bq — The Sustainable Development Goals #SDG🫶 (@ConnectSDGs) September 19, 2021

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 500 + words:

Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs are a list of 17 goals to build a better world for everyone. These goals are developed by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations. Let’s have a look at these sustainable development goals.

- Eradicate Poverty

- Zero Hunger

- Good Health and Well-being

- Quality Education

- Gender Equality

- Clean Water and Sanitation

- Affordable and Clean Energy

- Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

- Reduced Inequalities

- Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Responsible Consumption and Production

- Climate Action

- Life Below Water

- Life on Land

- Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Partnership for the Goals

Essay Format

Before drafting an essay on Sustainable Development, students need to get familiarised with the format of essay writing, to know how to structure the essay on a given topic. Take a look at the following pointers which elaborate upon the format of a 300-350 word essay.

Introduction (50-60 words) In the introduction, students must introduce or provide an overview of the given topic, i.e. highlighting and adding recent instances and questions related to sustainable development. Body of Content (100-150 words) The area of the content after the introduction can be explained in detail about why sustainable development is important, its objectives and highlighting the efforts made by the government and various institutions towards it. Conclusion (30-40 words) In the essay on Sustainable Development, you must add a conclusion wrapping up the content in about 2-3 lines, either with an optimistic touch to it or just summarizing what has been talked about above.

How to write the introduction of a sustainable development essay? To begin with your essay on sustainable development, you must mention the following points:

- What is sustainable development?

- What does sustainable development focus on?

- Why is it useful for the environment?

How to write the conclusion of a sustainable development essay? To conclude your essay on sustainable development, mention why it has become the need of the hour. Wrap up all the key points you have mentioned in your essay and provide some important suggestions to implement sustainable development.

The importance of sustainable development is that it meets the needs of the present generations without compromising on the needs of the coming future generations. Sustainable development teaches us to use our resources correctly. Listed below are some points which tell us the importance of sustainable development.

- Focuses on Sustainable Agricultural Methods – Sustainable development is important because it takes care of the needs of future generations and makes sure that the increasing population does not put a burden on Mother Earth. It promotes agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and effective seeding techniques.

- Manages Stabilizing the Climate – We are facing the problem of climate change due to the excessive use of fossil fuels and the killing of the natural habitat of animals. Sustainable development plays a major role in preventing climate change by developing practices that are sustainable. It promotes reducing the use of fossil fuels which release greenhouse gases that destroy the atmosphere.

- Provides Important Human Needs – Sustainable development promotes the idea of saving for future generations and making sure that resources are allocated to everybody. It is based on the principle of developing an infrastructure that is can be sustained for a long period of time.

- Sustain Biodiversity – If the process of sustainable development is followed, the home and habitat of all other living animals will not be depleted. As sustainable development focuses on preserving the ecosystem it automatically helps in sustaining and preserving biodiversity.

- Financial Stability – As sustainable development promises steady development the economies of countries can become stronger by using renewable sources of energy as compared to using fossil fuels, of which there is only a particular amount on our planet.

Mentioned below are some important examples of sustainable development. Have a look:

- Wind Energy – Wind energy is an easily available resource. It is also a free resource. It is a renewable source of energy and the energy which can be produced by harnessing the power of wind will be beneficial for everyone. Windmills can produce energy which can be used to our benefit. It can be a helpful source of reducing the cost of grid power and is a fine example of sustainable development.

- Solar Energy – Solar energy is also a source of energy which is readily available and there is no limit to it. Solar energy is being used to replace and do many things which were first being done by using non-renewable sources of energy. Solar water heaters are a good example. It is cost-effective and sustainable at the same time.

- Crop Rotation – To increase the potential of growth of gardening land, crop rotation is an ideal and sustainable way. It is rid of any chemicals and reduces the chances of disease in the soil. This form of sustainable development is beneficial to both commercial farmers and home gardeners.

- Efficient Water Fixtures – The installation of hand and head showers in our toilets which are efficient and do not waste or leak water is a method of conserving water. Water is essential for us and conserving every drop is important. Spending less time under the shower is also a way of sustainable development and conserving water.

- Sustainable Forestry – This is an amazing way of sustainable development where the timber trees that are cut by factories are replaced by another tree. A new tree is planted in place of the one which was cut down. This way, soil erosion is prevented and we have hope of having a better, greener future.

Related Articles

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 global goals established by the United Nations in 2015. These include: No Poverty Zero Hunger Good Health and Well-being Quality Education Gender Equality Clean Water and Sanitation Affordable and Clean Energy Decent Work and Economic Growth Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure Reduced Inequality Sustainable Cities and Communities Responsible Consumption and Production Climate Action Life Below Water Life on Land Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions Partnerships for the Goals

The SDGs are designed to address a wide range of global challenges, such as eradicating extreme poverty globally, achieving food security, focusing on promoting good health and well-being, inclusive and equitable quality education, etc.

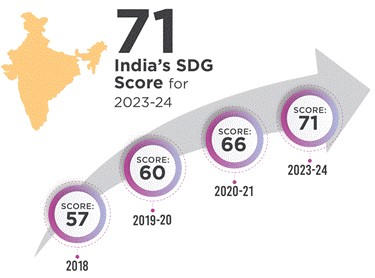

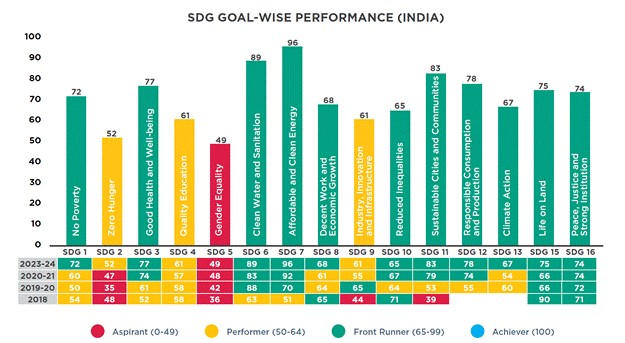

India is ranked #111 in the Sustainable Development Goal Index 2023 with a score of 63.45.

Hence, we hope that this blog helped you understand the key features of an essay on sustainable development. If you are interested in Environmental studies and planning to pursue sustainable tourism courses , take the assistance of Leverage Edu ’s AI-based tool to browse through a plethora of programs available in this specialised field across the globe and find the best course and university combination that fits your interests, preferences and aspirations. Call us immediately at 1800 57 2000 for a free 30-minute counselling session

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Thanks a lot for this important essay.

NICELY AND WRITTEN WITH CLARITY TO CONCEIVE THE CONCEPTS BEHIND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY.

Thankyou so much!

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2025

September 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Sustainable Development Essay

500+ words essay on sustainable development.

Sustainable development is a central concept. It is a way of understanding the world and a method for solving global problems. The world population continues to rise rapidly. This increasing population needs basic essential things for their survival such as food, safe water, health care and shelter. This is where the concept of sustainable development comes into play. Sustainable development means meeting the needs of people without compromising the ability of future generations. In this essay on sustainable development, students will understand what sustainable development means and how we can practise sustainable development. Students can also access the list of CBSE essay topics to practise more essays.

What Does Sustainable Development Means?

The term “Sustainable Development” is defined as the development that meets the needs of the present generation without excessive use or abuse of natural resources so that they can be preserved for the next generation. There are three aims of sustainable development; first, the “Economic” which will help to attain balanced growth, second, the “Environment”, to preserve the ecosystem, and third, “Society” which will guarantee equal access to resources to all human beings. The key principle of sustainable development is the integration of environmental, social, and economic concerns into all aspects of decision-making.

Need for Sustainable Development?

There are several challenges that need attention in the arena of economic development and environmental depletion. Hence the idea of sustainable development is essential to address these issues. The need for sustainable development arises to curb or prevent environmental degradation. It will check the overexploitation and wastage of natural resources. It will help in finding alternative sources to regenerate renewable energy resources. It ensures a safer human life and a safer future for the next generation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need to keep sustainable development at the very core of any development strategy. The pandemic has challenged the health infrastructure, adversely impacted livelihoods and exacerbated the inequality in the food and nutritional availability in the country. The immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic enabled the country to focus on sustainable development. In these difficult times, several reform measures have been taken by the Government. The State Governments also responded with several measures to support those affected by the pandemic through various initiatives and reliefs to fight against this pandemic.

How to Practise Sustainable Development?

The concept of sustainable development was born to address the growing and changing environmental challenges that our planet is facing. In order to do this, awareness must be spread among the people with the help of many campaigns and social activities. People can adopt a sustainable lifestyle by taking care of a few things such as switching off the lights when not in use; thus, they save electricity. People must use public transport as it will reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. They should save water and not waste food. They build a habit of using eco-friendly products. They should minimise waste generation by adapting to the principle of the 4 R’s which stands for refuse, reduce, reuse and recycle.

The concept of sustainable development must be included in the education system so that students get aware of it and start practising a sustainable lifestyle. With the help of empowered youth and local communities, many educational institutions should be opened to educate people about sustainable development. Thus, adapting to a sustainable lifestyle will help to save our Earth for future generations. Moreover, the Government of India has taken a number of initiatives on both mitigation and adaptation strategies with an emphasis on clean and efficient energy systems; resilient urban infrastructure; water conservation & preservation; safe, smart & sustainable green transportation networks; planned afforestation etc. The Government has also supported various sectors such as agriculture, forestry, coastal and low-lying systems and disaster management.

Students must have found this essay on sustainable development useful for practising their essay writing skills. They can get the study material and the latest updates on CBSE/ICSE/State Board/Competitive Exams, at BYJU’S.

Frequently Asked Questions on Sustainable development Essay

Why is sustainable development a hot topic for discussion.

Environment change and constant usage of renewable energy have become a concern for all of us around the globe. Sustainable development must be inculcated in young adults so that they make the Earth a better place.

What will happen if we do not practise sustainable development?

Landfills with waste products will increase and thereby there will be no space and land for humans and other species/organisms to thrive on.

What are the advantages of sustainable development?

Sustainable development helps secure a proper lifestyle for future generations. It reduces various kinds of pollution on Earth and ensures economic growth and development.

| CBSE Related Links | |

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Climate Change Is a Challenge For Sustainable Development

- This page in:

Rachel Kyte Gaidar Forum Moscow, Russian Federation

Climate change is the most significant challenge to achieving sustainable development, and it threatens to drag millions of people into grinding poverty.

At the same time, we have never had better know-how and solutions available to avert the crisis and create opportunities for a better life for people all over the world.

Climate change is not just a long-term issue. It is happening today, and it entails uncertainties for policy makers trying to shape the future.

EFFECTS ON RUSSIA

In 2008, the Russian National Hydrometeorological Service (Roshydromet) found that winter temperatures had increased by 2 to 3 degrees Celsius in Siberia over the previous 120-150 years, while average global temperature rose about 0.7 degrees during the same period.

Russia is projected to cross the 2°C threshold earlier than the world on average if significant and effective mitigation is not forthcoming. By 2100, the northern half of Asia, including Russia, is likely to experience a temperature increase of 6 to 16°C, compared to approximately 4°C global mean temperature increase.

While warming might have some potential gains for Russia, the adverse effects include more floods, windstorms, heat waves, forest fires, and the melting of permafrost.

Globally, permafrost is thought to hold about 1,700 gigatons of carbon – and near-shore seabeds in the Eastern Siberian Sea hold a similar amount in methane hydrates that could potentially be destabilized in a warmer world, as well. This is compared to 850 gigatons of carbon currently in the Earth’s atmosphere. Of this, 190 gigatons are stored just in the upper 30 cm of permafrost, the layers that area most vulnerable to melting and the irreversible release of methane. The release of even a small portion into the atmosphere could dramatically compound the challenge already presented from anthropogenic sources, potentially wiping out any hard-won mitigation gains.

Russia hosts perhaps 70 percent of methane in circumpolar permafrost, as well as the methane hydrates in the East Siberian Sea. Permafrost warming of up to 2°C in parts of the European Russia has already been observed.

Russia will be front and center for any efforts to deal with thawing permafrost and Russian leadership is much needed to better understand its effects for the global climate as well as finding solutions for effective adaptation. There is no time to lose.

In Yakutsk, collapsing ground caused by melting permafrost has damaged buildings, airport runways, and other infrastructure. In 2010, the Ministry of Emergency Situations estimated that a quarter of the housing stock in Russia’s Far North would be destroyed by 2030.

Analyses indicate that about 60 percent of infrastructure in the Usa Basin in Northeast European Russia is located in the "high risk" permafrost area, which is projected to thaw in the future. This region is an area of high industrial and urban development, like coal mines, hydrocarbon extraction sites, railways, and pipelines. Yet the timing of this thaw remains uncertain – potentially a few decades or as long off as a century away.

DECISION MAKING UNDER UNCERTAINTY

Policy makers all over the world are facing similar challenges. While we certainly know that the climate will change, there is great uncertainty as to what the local or regional impacts will be and what will be the impacts on societies and economies. Coupled with this is often great disagreement among policy makers about underlying assumptions and priorities for action.

Many decisions to be made today have long-term consequences and are sensitive to climate conditions – water, energy, agriculture, fisheries and forests, and disasters risk management. We simply can’t afford to get it wrong.

However, sound decision making is possible if we use a different approach. Rather than making decisions that are optimized to a prediction of the future, decision makers should seek to identify decisions that are sound no matter what the future brings. Such decisions are called “robust.”

For example, Metropolitan Lima already has major water challenges: shortages and a rapidly growing population with 2 million underserved urban poor. Climate models suggest that precipitation could decrease by as much as 15 percent, or increase by as much as 23 percent. The World Bank is partnering with Lima to apply tested, state-of-the-art methodologies like Robust Decision Making to help Lima identify no-regret, robust investments. These include, for example, multi-year water storage systems to manage droughts and better management of demand for water. This can help increase Lima’s long-term water security, despite an increasingly unpredictable future.

WORKING WHERE IT MATTERS MOST

Each country will need to find its own ways to deal with uncertainties and find its best options for low-carbon growth and emissions reduction. While they vary, every country has them.

One example: Russia has made remarkable progress since 2005 in reducing the flaring of gas from oil production, but it is still the world’s largest gas flarer. And it is situated in a region from where black carbon from the flares reaches the Arctic snow and ice cap, which diminishes the cap’s reflective power (albedo). The World Bank Group is appreciative of the successful cooperation with Russia's Khanty-Mansiysk region in the Global Gas Flaring Reduction partnership (GGFR). With more Russian partners, in particular from Russian state oil companies, the impact could be even greater.

Russia’s forests provide the largest land-based carbon storage in the world. Better forest management and improving forest fire response – a long-standing field of cooperation between Russia and the World Bank Group – are another example to reconcile growth and emissions reductions.

Options for countries all over the world include a mix of technology development that lowers air pollution; increasing investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency, expanding urban public transport; improving waste and water management; and better planning for when disasters strike.

Each of these climate actions can be designed to bring short-term benefits and lower current and future emissions.

To move forward on the global level at the required scale, we must drive mitigation action in top-emitting countries, get prices and incentives right, get finance flowing towards low-carbon green growth, and work where it matters most.

Prices: Putting a price on carbon and removing harmful fossil fuel subsidies are necessary steps towards directing investment to low-carbon growth and avoiding a 4°C warmer world. We are working with others to help lay the groundwork for a robust price on carbon and supporting the removal of harmful fossil fuel subsidies. An ambitious global agreement could help establish stronger carbon prices and should include commitments to accelerate fossil fuel subsidy reform and other fiscal or tax policy measures in support of low carbon and climate resilient development.

Finance flowing: Progress on the provision of climate finance is critical. Governments must deliver a clear strategy for mobilizing the promised $100 billion in climate finance. This $100 billion is doubly important in that it must be used to mobilize effectively private investment and other finance.

Climate change increases the costs of development in the poorest countries by between 25 and 30 percent. For developing countries, the annual cost of infrastructure that is resilient to climate change is around $1.2 trillion to $1.5 trillion, resulting in a yearly $700 billion gap in financing. It will take combining efforts of development banks, financial institutions, export credit agencies, institutional investors, and public budgets to meet the climate and development challenge.

All public finance should be used to leverage private capital and fill gaps in the market where private finance is not flowing. Also, it must be deployed in a way that the least amount leverages the maximum amount from public and/or private sources. We are not dealing with how to jump start something in which the private sector is not interested, but how we create the framework within which the now small but significant momentum is captured, disseminated, and accelerated and the speed-bumps are removed and setbacks avoided.

At the World Bank Group we are committed to working where it matters most:

By 2050 two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in cities. Helping developing country cities access private financing and achieve low-carbon, climate-resilient growth and avoid locking in carbon intensive infrastructure is one of the smartest investments we can make. Every dollar invested in building creditworthiness of a developing country city will mobilize $100 dollars in private financing for low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure.

To feed 9 billion people nutritiously by 2050 we need to make agriculture resilient, more productive in changing landscapes, and aggressively reduce food waste. Making agriculture work for the people and the environment is one of the most pressing tasks at hand. We need climate-smart agriculture that increases yields and incomes, builds resilience, and reduces emissions while potentially capturing carbon.

The World Bank Group supports the Sustainable Energy for All goals of doubling both the rate of improvement of energy efficiency and the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix from 18 percent to 36 percent by 2030. Reaching these goals is key to low-carbon growth.

- BLOGS Rachel Kyte's Blog

- Europe and Central Asia

Newsletters

You have clicked on a link to a page that is not part of the beta version of the new worldbank.org. Before you leave, we’d love to get your feedback on your experience while you were here. Will you take two minutes to complete a brief survey that will help us to improve our website?

Feedback Survey

Thank you for agreeing to provide feedback on the new version of worldbank.org; your response will help us to improve our website.

Thank you for participating in this survey! Your feedback is very helpful to us as we work to improve the site functionality on worldbank.org.

- Get involved

Development challenges and solutions

The challenges.

UNDP’s work, adapted to a range of country contexts, is framed through three broad development settings. These three development challenges often coexist within the same country, requiring tailored solutions that can adequately address specific deficits and barriers. Underpinning all three development challenges is a set of core development needs, including the need to strengthen gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls, and to ensure the protection of human rights.

Outcome 1: Eradication of poverty in all its forms and dimensions

It's estimated that approximately 700 million people still live on less than US$1.90 per day, a total of 1.3 billion people are multi-dimensionally poor, including a disproportionate number of women and people with disabilities and 80 percent of humanity lives on less than US$10 per day. Increasingly, middle-income countries account for a large part of this trend.

UNDP is looking at both inequalities and poverty in order to leave no one behind, focusing on the dynamics of exiting poverty and of not falling back. This requires addressing interconnected socio-economic, environmental and governance challenges that drive people into poverty or make them vulnerable to falling back into it. The scale and rapid pace of change necessitates decisive and coherent action by many actors at different levels to advance poverty eradication in all forms and dimensions. UNDP works to ensure responses are multisectoral and coherent from global to local.

Outcome 2: Accelerating structural transformations for sustainable development

The disempowering nature of social, economic, and political exclusion results in ineffective, unaccountable, non-transparent institutions and processes that hamper the ability of states to address persistent structural inequalities.

UNDP will support countries as they accelerate structural transformations by addressing inequalities and exclusion, transitioning to zero-carbon development and building more effective governance that can respond to megatrends such as globalization, urbanization and technological and demographic changes.

Outcome 3: Building resilience to crisis and shocks

Some countries are disproportionately affected by shocks and stressors such as climate change, disasters, violent extremism, conflict, economic and financial volatility, epidemics, food insecurity and environmental degradation. Climate-related disasters have increased in number and magnitude, reversing development gains, aggravating fragile situations, and contributing to social upheaval. Conflict, sectarian strife and political instability are on the rise and more than 1.6 billion people live in fragile or conflict-affected settings.

Around 258 million people live outside their countries of origin and 68.5 million are displaced. Disasters and the effects of climate change have displaced more people than ever before – on average 14 million people annually. Major disease outbreaks result in severe economic losses from the effect on livelihoods or decline in household incomes and national GDPs, as demonstrated by the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014-2015.

To return to sustainable development, UNDP is strengthening resilience by supporting governments to take measures to manage risk, prevent, respond and recover more effectively from shocks and crises and address underlying causes in an integrated manner. Such support builds on foundations of inclusive and accountable governance, together with a strong focus on gender equality, the empowerment of women and girls and meeting the needs of vulnerable groups, to ensure that no one is left behind.

The road to success

To fulfill the aims of the Strategic Plan with the multi-dimensionality and complexity that the 2030 Agenda demands, UNDP is implementing six cross-cutting approaches to development, known as Signature Solutions. A robust, integrated way to put our best work – or 'signature' skillset – into achieving the Sustainable Development Goals .

UNDP’s Signature Solutions are cross-cutting approaches to development— for example, a gender approach or resilience approach can be applied to any area of development, or to any of the SDGs.

Keeping people out of poverty

Today, 700 million people live on less than $1.90 per day and a total of 1.3 billion people are multi-dimensionally poor. People stay in or fall back into poverty because of a range of factors—where they live, their ethnicity, gender, a lack of opportunities, and others.

It’s no coincidence that our first Signature Solution relates directly to the first SDG: to eradicate all forms of poverty, wherever it exists. For UNDP, helping people to get out and stay out of poverty is our primary focus. It features in our work with governments, communities and partners across the 170 countries and territories in which we operate.

UNDP interventions help eradicate poverty, such as by creating decent jobs and livelihoods, providing social safety nets, boosting political participation, and ensuring access to services like water, energy, healthcare, credit, and productive assets. Our Signature Solution on poverty cuts across our work on all the SDGs, whether it’s decent work or peace and justice.

Governance for peaceful, just, and inclusive societies

People’s lives are better when government is efficient and responsive. When people from all social groups are included in decision-making that affects their lives, and when they have equal access to fair institutions that provide services and administer justice, they will have more trust in their government.

The benefits of our work on governance are evident in all the areas covered by the SDGs, whether it’s climate action or gender equality. UNDP’s governance work spans a wide range of institutions, from national parliaments, supreme courts, and national civil services through regional and local administrations, to some of the geographically remotest communities in the world. We work with one out of every three parliaments on the planet, help countries expand spaces for people’s participation, and improve how their institutions work, so that all people can aspire to a sustainable future with prosperity, peace, justice and security.

Crisis prevention and increased resilience

Crises know no borders. More than 1.6 billion people live in fragile and/or conflict-affected settings, including 600 million young people. More people have been uprooted from their homes by war and violence and sought sanctuary elsewhere than at any time since the Second World War. Poverty, population growth, weak governance and rapid urbanization are driving the risks associated with such crises.

UNDP helps reduce these risks by supporting countries and communities to better manage conflicts, prepare for major shocks, recover in their aftermath, and integrate risk management into their development planning and investment decisions. The sooner that people can get back to their homes, jobs, and schools, the sooner they can start thriving again. Resilience building is a transformative process of strengthening the capacity of people, communities, institutions, and countries to prevent, anticipate, absorb, respond to and recover from crises. By implementing this Signature Solution, we focus on capacities to address root causes of conflict, reduce disaster risk, mitigate and adapt to climate change impacts, recover from crisis, and build sustainable peace. This has an impact that not only prevents or mitigates crises, but also has an effect on people’s everyday lives across all SDGs.

Environment: nature-based solutions for development

Healthy ecosystems are at the heart of development, underpinning societal well-being and economic growth. Through nature-based solutions, such as the sustainable management and protection of land, rivers and oceans, we help ensure that countries have adequate food and water, are resilient to climate change and disasters, shift to green economic pathways, and can sustain work for billions of people through forestry, agriculture, fisheries and tourism.

A long-standing partner of the Global Environment Facility, and now with the second-largest Green Climate Fund portfolio, UNDP is the primary actor on climate change in the United Nations. Our aim is to help build the Paris Agreement and all environmental agreements into the heart of countries’ development priorities. After all, the food, shelter, clean air, education and opportunities of billions of people depend on getting this right.

Clean, affordable energy

People can’t prosper without reliable, safe, and affordable energy to power everything from lights to vehicles to factories to hospitals. And yet, 840 million people worldwide have no access to electricity, and 2.9 billion people use solid fuels to cook or heat their homes, exposing their families to grave health hazards and contributing to vast deforestation worldwide 3 . In these and other ways, energy is connected to every one of the SDGs.

UNDP helps countries transition away from the use of finite fossil fuels and towards clean, renewable, affordable sources of energy. Our sustainable energy portfolio spans more than 110 countries, leveraging billions of dollars in financing, including public and private sources. With this financial support, we partner with cities and industries to increase the share of renewables in countries’ national energy mix; establish solar energy access to people displaced by conflict; fuel systemic change in the transport industry; and generate renewable ways to light homes for millions of people.

Women's empowerment and gender equality

Women’s participation in all areas of society is essential to make big and lasting change not only for themselves, but for all people. Women and girls make up a disproportionate share of people in poverty, and are more likely to face hunger, violence, and the impacts of disaster and climate change. They are also more likely to be denied access to legal rights and basic services.

UNDP has the ability and responsibility to integrate gender equality into every aspect of our work. Gender equality and women’s empowerment is a guiding principle that applies to everything we do, collaborating with our partner countries to end gender-based violence, tackle climate change with women farmers, and advance female leadership in business and politics.

[1] OECD , States of Fragility 2016: Understanding Violence (Paris, 2016), p. 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267213-en .

[2] sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030, p.9. http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/43291 ., [3] source: iea, irena, unsd, wb, who, 2019, tracking sdg7: the energy progress report 2019, washington, dc..

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

sustainable development

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Salt Lake Community College Pressbooks - Introduction to Human Geography - Sustainable Development

- Academia - Sustainable Development and its Dimensions

sustainable development , approach to social, economic, and environmental planning that attempts to balance the social and economic needs of present and future human generations with the imperative of preserving, or preventing undue damage to, the natural environment .

Sustainable development lacks a single detailed and widely accepted definition. As a general approach to human development , it is frequently understood to encompass most if not all of the following goals, ideals, and values:

- A global perspective on social, economic, and environmental policies that takes into account the needs of future generations

- A recognition of the instrumental value of a sound natural environment , including the importance of biodiversity

- The protection and appreciation of the needs of Indigenous cultures

- The cultivation of economic and social equity in societies throughout the world

- The responsible and transparent implementation of government policies

The intellectual underpinnings of sustainable development lie in modern natural resource management , the 20th-century conservation and environmentalism movements, and progressive views of economic development . The first principles of what later became known as sustainable development were laid out at the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment , also called the Stockholm Conference. The conference concluded that continued development of industry was inevitable and desirable but also that every citizen of the world has a responsibility to protect the environment. In 1987 the UN -sponsored World Commission on Environment and Development issued the Brundtland Report (also called Our Common Future ), which introduced the concept of sustainable development—defining it as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”—and described how it could be achieved. At the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (also called the Earth Summit), more than 178 countries adopted Agenda 21, which outlined global strategies for restoring the environment and encouraging environmentally sound development.

Since that time, sustainable development has emerged as a core idea of international development theory and policy. However, some experts have criticized certain features of the concept, including:

- Its generality or vagueness, which has led to a great deal of debate over which forms or aspects of development qualify as “sustainable”

- Its lack of quantifiable or objectively measurable goals

- Its assumption of the inevitability and desirability of industrialization and economic development

- Its failure to ultimately prioritize human needs or environmental commitments, either of which may reasonably be considered more important in certain circumstances

Although the implementation of sustainable development has been the subject of many social scientific studies—so many, in fact, that sustainable development science is sometimes viewed as a distinct field—a number of public intellectuals and scholars have argued that the core value of sustainable development lies in its aspirational perspective. These writers have argued that merely attempting to balance social, economic, and environmental policymaking—the three “pillars” of sustainable development—is an inherently positive practice. Even if an imbalance of results is to a certain extent inevitable, it is better that policymakers at least attempt to achieve a balance. Abandoning the notion of sustainable development altogether, they argue, would likely worsen social, economic, and environmental conditions throughout the world, thus undermining all three pillars.

Despite widespread criticism , sustainable development has emerged as a core feature of national and international policymaking, particularly by agencies of the United Nations . In 2015 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which included 17 sweeping goals designed to create a globally equitable society alongside a thriving environment.

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Global Sustainability

- > Volume 2

- > Current challenges to the concept of sustainability

Article contents

Non-technical summary.

- Ecological dimension: reflection on the conditions and consequences of human activities

- Political dimension: sustainability as cross-sectional political guideline

- Ethical dimension: intergenerational and global responsibility

- Socio-economic dimension: operationalizing the principle of sustainability

- Democratic dimension: pluralism, participation and democratic innovation

- Cultural dimension: lifestyle and a new model of wealth

- Theological dimension: belief in creation and sustainability

Current challenges to the concept of sustainability

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 February 2019

In this paper we discuss current challenges to the sustainability concept. This article focuses on seven dimensions of the concept. These dimensions are crucial for understanding sustainability. Even today, the literature contains basic misunderstandings about these seven dimensions. This article sketches such fallacies in the context of global and planetary sustainability. The sustainability concept has been criticized as a content-empty ‘fuzzy notion’ or non-committal ‘all-purpose glue’. This article thus has a critical intention of reflecting the sustainability concept accurately. The aim is to contribute a better understanding of the concept.

This article focuses on current challenges to the sustainability concept. The questions that are asked address the following seven dimensions, which are indispensable for understanding the term ‘sustainability’ and its normative content: (1) ecological dimension, (2) political dimension, (3) ethical dimension, (4) socio-economic dimension, (5) democratic dimension, (6) cultural dimension, and (7) theological dimension.

This paper has a critical intention. From our perspective, basic misunderstandings exist about these seven dimensions. We thus present and discuss seven fallacies. These fallacies are partly to blame for the fact that in recent years, the discourse about the environment and development has led to a dead-end, discrediting the term ‘sustainability’. The concept is seen as a seemingly content-empty ‘fuzzy notion’ or a non-committal ‘all-purpose glue’. The aim of this paper is to contribute to a better understanding of the concept of sustainability by presenting a differentiated analysis of its content. This effort highlights the ‘the need of an ethics of planetary sustainability’ (Losch, Reference Losch 2018 , p. 6), which will probably become an urgent topic to discuss at different levels.

1. Ecological dimension: reflection on the conditions and consequences of human activities

The first fallacy: sustainability refers mainly to a principle of passive limitation or regulation of human activities.

The principle of regulating sustainability was first formulated by the Saxon mining officer Hans Carl von Carlowitz in his book Silvicultura oeconomica in 1713 (von Carlowitz, Reference von Carlowitz 1713 , p. 105f.). This principle was a feature of the early Age of Enlightenment. Carlowitz, who ‘published the first comprehensive treatise about sustainable yield forestry’ (Silvius, Reference Silvius and Khosrow-Pour 2018 , p. 332), used the term ‘sustainable’ to denote the opposite of ‘neglectful’. Therefore, sustainability does not refer to a principle of passive limitation, but rather to the optimal planting and cultivation of trees that are suitable for a specific soil and demand. From the start, sustainability has been more than a rule for forest preservation. However, summarizing such rules for management makes the idea memorable and suitable for an initial understanding of the concept. In general terms, the principle means not using more resources than can be regenerated during the same period.

The core of sustainability, however, entails the planning and anticipating of the economy in the ecological metabolic cycle and its rhythms of time (this topic is discussed further under point 6: the cultural dimension). Therefore, it is necessary to reflect on the conditions and consequences of human activities for current and future generations. Sustainable development must be understood as a process of actively and innovatively searching, learning and shaping the present and future of human activities on Earth – and in outer space. The term ‘sustainable’ is not just a synonym for ‘good’ (Ostheimer, Reference Ostheimer, Vogt and Ostheimer 2013 ), and the future is generally difficult to predict (see point 3: the ethical dimension). Thus, questions such as How to manage the risk? How to manage the failure? must be asked in this context. However, Ulrich Beck did not directly use ‘sustainability’ in his analyses of ‘risk in society’ and ‘reflexive modernity’ (Beck, Reference Beck 1986 , p. 107f.). The term ‘future-oriented’ as a claim to justice, solidarity or responsibility is the most common normative description of sustainability. Trying more and more to shape the unplannable, the sustainability concept will be acknowledged as a political guideline rather than as just a principle of passive limitation or regulation of human actions. Sustainability does not refer only to the limits of what is allowed or forbidden. It is not simply about preserving what exists, but rather about making room for nature's vital forces.

Generalizing the principle of sustainability as a rule for good resource management, it might seem that the property rights of one generation's natural resources are never unlimited. Sustainability must not be viewed simply as a rule of balance and self-sufficiency for preserving the natural capital stock (see point 4: the socio-economic dimension). It rather has the character of a ‘usus fructus’: a right to acquire yields, if the potential of generating yields is preserved. Because humankind did not create nature, humans cannot claim ownership in an absolute sense.

The above line of thought, which was presented by the liberal philosopher John Locke as early as the 17th century, is well known today. It features in the monotheistic religions with their belief in God as the owner of His creation. Whether people believe in God or not, sustainability always requires critical reflection on the notion of ‘property’. Hence, it is crucial to reflect on the ‘ownership of natural resources’. The topic of property rights over natural resources must be discussed, not only for resources on Earth but also beyond. To whom do the resources of Earth and outer space belong (e.g. in the case of space mining)? Who profits from the exploitation of near-Earth objects (e.g. asteroids)?

International agreements must determine these property questions in a fair way for all humankind, so that sustainability can become a mediating concept. The United Nations, in its Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS), has established a Working Group on the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities (UNOOSA, 2018 ). This group has ‘addressed thematic areas, including sustainable space utilization supporting sustainable development on Earth’ (Losch, Reference Losch 2018 , p. 1).

2. Political dimension: sustainability as cross-sectional political guideline

The second fallacy: sustainability is the equivalent consideration of ecological, social and economic factors.

At the United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the global community agreed on the central theme of ‘sustainable development’. This theme was defined as a Program of Actions for the 21st Century (so-called Agenda 21 ), which became a decisive document in the global acceptance of sustainability. However, more than 25 years later, the term ‘sustainable development’ still lacks precise understanding or implementation as a guiding principle in global partnership. The implementation of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), by achieving all 169 targets in various areas, was recently decided at the highest global level by the United Nations in 2015 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018 ).

The systematic accentuation of the interdependences among ecological, social and economic factors forms the core of the United Nations approaches to sustainability. However, the widely discussed ‘three pillars concept’ is misleading. Hence, ‘equality’ does not have an exact meaning in this context. The three pillars concept harbours both a deep truth and a danger. It is true that from the ethical and political viewpoints, the strategic point of sustainability is to broaden the ecological perspective through social and economic approaches. Environmental policy is integrated into socio-economic concepts of development with regard to strengthening local knowledge cultures. Such effort is understood as the ecological dimension of poverty prevention. For this purpose, sustainable actions must not remain abstract but must become concrete in the context of various development models (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom 2005 ; Pope Francis, 2015 ).

However, it would be incorrect to use the three pillars concept to claim that ecology, economy and social affairs all have equal value. These are different areas which cannot be compared directly. A scholar who defines ‘sustainability’ as the sum of social, ecological and economic objectives would fall victim to a fallacy. Because hardly anything exists that cannot be subsumed under these three notions, the range of the concept becomes almost infinite (Vogt, Reference Vogt 2013 ). For the term ‘sustainability’ to make sense, it should not be defined as a sum but rather as the interdependence and interaction of ecological, social and economic factors. It is not about the totality of eco-social and economic problems. Rather, it concerns a cross-sectional policy, based on interdisciplinary analyses and a systemic way of thinking about the re-nationalization of environmental problems (Reis, Reference Reis 2003 ).

Although the SDGs do not commit the mentioned fallacy in most parts of the text, they sometimes take too little account of central global challenges such as increasing resource consumption and population growth, externalization of ecological and social costs. Some goals even seem to be contradictory. Within the text, there is sometimes a conflict of objectives between economic growth that is to be achieved (for instance in chapter 8 of the SDGs) and ecological limits of nature. This needs to be discussed in even more detail in order to strengthen the value of the concept of sustainability.

3. Ethical dimension: intergenerational and global responsibility

The third fallacy: intergenerational justice, as the normative core of sustainability, guarantees future generations an equal amount of natural resources.

When scholars talk or write about sustainability and the perspective of intergenerational justice, they often refer to the definition in the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future, published in 1987. That definition reads as follows: ‘Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987 , p. 41). The problems involve setting standards for intergenerational justice. Questions include: can there be a guaranteed right to an equal amount of natural resources with regard to historically contingent developments? Are future generations possible legal entities?

In view of the gross differences in geographical, cultural and historical conditions in which people live, postulates of (absolute) equality are highly problematic. As the future cannot be calculated, and the needs and competences of future people are not fully known, freedom should be given a high priority. Thus, the idea of equal distribution of resources among generations is of little practical help in many areas. The aim should rather be to leave to posterity a world that offers enough free space and enough chances. This would enable future generations to make their own decisions and further develop their capabilities. To examine factors in the relationship between people and commodities, the capability approach can be used (Sen, Reference Sen 1999 ). Therefore, sustainability requires openness to allow for unplanned things.

Sustainability is based on resilience in dealing with stress and surprises, as well as on transformational competence in designing transitions. Hence, sustainability extends beyond a focus on desirable goals to critical reflection on forces and obstacles that either enable or prevent a transformational process in society. In other words, intergenerational justice requires awareness of complexity and process, so that people can deal with issues related to power, ignorance and shaping the unplannable. This need becomes more urgent when the global and intergenerational perspective is augmented with factors related to extra-terrestrial life (life beyond Earth). The demands and rights of these entities, if they exist, might also need to be considered. Should we be thinking about the protection of planets as potential habitats for extra-terrestrial life or future generations? (Losch, Reference Losch 2018 ).

In the logic of its argument, the United Nations’ (Rio de Janeiro) sustainability concept did not invoke specifically ecological terms. Instead it was based on broadening the understanding of ‘equity’ in global and intergenerational dimensions. In other words, the main interest was global and intergenerational equity (Reis, Reference Reis 2003 ). This was a logical consequence of globalization, whose seemingly unlimited use of space and time in economic and social interactions raises ethical questions. Globalization necessitates an extension of ethics regarding the limits of natural resources (Vogt, Reference Vogt 2014 ).

The scientific debate hinges on the question of whether ‘equity’ means ‘equality’ in egalitarian terms. If so – for example, in the study ‘Zukunftsfähiges Deutschland’ (Loske & Bleischwitzt, Reference Loske and Bleischwitz 1996 ), two ethical postulates are derived. On the one hand is equal chances for future generations, and on the other hand, equal rights to globally accessible resources.

Currently, the central reliability test for intergenerational responsibility on Earth is carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) equity. A human rights approach would stress that fighting poverty must be integrated systematically and dealt with in terms of ethical priorities. Normatively, the fight against poverty should arguably have moral priority over climate protection. However, especially in the ecologically sensitive habitats of the Global South, environmental protection is a decisive way of combatting poverty and safeguarding human rights. Climate change, water pollution, soil degradation and deforestation have long been the main causes of poverty in these regions (Potsdam Institut für Klimafolgenforschung, 2010 ; Vogt, Reference Vogt 2013 ).

For leading and developed nations, CO 2 equity means those countries must reduce their CO 2 output by at least 80% by 2050 (relative to 1990). Thus, from a scientific perspective, climate equity requires – above all – improving data on and calculations of CO 2 cycles. For example, factors such as aircraft fuels and the sink function of woods and soils should be considered. Equality regarding access to natural resources as a basis for intergenerational and global justice is a claim which needs far more normative reflection (Kistler, Reference Kistler 2017 ).

4. Socio-economic dimension: operationalizing the principle of sustainability

The fourth fallacy: sustainability means preserving an equilibrium system in nature that does not consume more resources than it can regrow.

Sustainability manifests in the endeavour to preserve Earth's natural resources. Debate about natural resources aligns with the idea of ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ sustainability. Weak sustainability allows for the substitution of natural stock by an ecological, social or economic gain in value, whereas the strong sustainability interpretation does not (Münk, Reference Münk 1999 ). In addition, the notion of ‘strong sustainability’ can create misunderstanding of the three pillars concept. The seemingly equal standing of the three dimensions undermines the ecological postulate. According to the concept of strong sustainability, the exploitation of natural capital stock cannot be compensated for by a gain in economic value in a constrained sense.

The ecologist Wolfgang Haber suggested that the model of sustainability evident in nature amounts to an idealization of recycling and self-sufficiency concepts. Haber stated that this natural model cannot provide a meaningful model for modern urban civilizations (Haber, Reference Haber 1994 ). The conservation rule of so-called strong sustainability is based on an idealization of equilibrium models, which can be questioned both in evolutionary theory and in cultural history. As a rule, socio-ecological interactions are open systems.

The model of strong sustainability also incurs a methodological problem. In the model of strong sustainability, the term ‘resource’ is assumed to be a pre-social fact. However, something can be defined as a resource only once it has been shown to have utility value. A resource is, by definition, something that can be used or consumed; thus, it is a culture- and technology-dependent variable. For example, after hydrogen engines were invented and were in demand, hydrogen became a resource. Therefore, what constitutes a resource depends on relevant technological innovations and social demand. Through new and more efficient inventions, resources can be increased. If this argument is denied, the concept of sustainability degenerates into a passive principle of constraint.

Sustainability is not ‘strong’ when one assumes a naturalistic notion of resources. However, to do so, one would have to forget about the complex interdependence among socio-economic and ecological systems – which follow their own logic. The current backdrop is global crises related to climate change, financial crises, unemployment, hunger, lack of fresh water (in certain regions), loss of biodiversity, soil erosion and scarcity of resources – to name a few aspects of the many developmental crises of the early 21st century. Thus, operationalizing the concept of sustainability requires focusing on resilience for the future. Sustainability advocates should deal strongly with democratic processes of change.

5. Democratic dimension: pluralism, participation and democratic innovation

The fifth fallacy: the model of sustainability is a clearly defined objective. Approval of the concept of sustainability can simply be guaranteed by the widespread participation of affected groups.

Participation, and thus actor-oriented concepts, have central significance in sustainability. The third (and most creative) section of Agenda 21 of the United Nations Conference in Rio deals with this topic. In the implementation of sustainability, however, utopian exaggeration of the role of civil-society initiatives is often evident. This tendency can be described as the naivety of idealistically charged concepts among civil society. Eco-social protest movements are not intrinsically good. They are often based on a radical reduction of complexity which prevents a nuanced awareness of the factual problems. Sustainability also requires uncomfortable decisions, which are not fostered by a policy that is too much reliant on media approval.

Analyses by social scientists, and courageous political leadership, are necessary correctives for the utopian exaggeration of civil-society rationality, and for promoting joint responsibility in sustainability processes. The constructive dynamics of societal adaptation to the conditions of nature rest on innovation and cultural values. The objectives of sustainability must be integrated into scientific, technological and economic development. Such adaptation is possible within a framework which acknowledges the diverse preferences, worldviews and competences of a pluralistic society. Because of such openness, models of sustainability cannot present a fixed aim. Sustainability is rather a system of objectives with components. It embodies a pluralistic model, which can be represented in concrete terms through diverse societal processes in the areas of economy, science and culture (Vogt, Reference Vogt 2013 ).

The openness of sustainability demands the participatory shaping of public life by civil society. The active shaping of living spaces should not be decided exclusively by authorities (top-down) but must also grow slowly (bottom-up). Through recognition and participatory shaping, a consciousness of responsibility can thrive (Honneth, Reference Honneth 1994 ). Thus, participation is an essential element of the ethical principle of sustainability. Sustainability requires far-reaching democratic innovations. A multi-dimensional approach is needed, which takes up the practices of sustainability employed by pioneer groups. This approach would open up spaces in civil society for a change in values. Such change must be secured structurally through changing the social institutions.

6. Cultural dimension: lifestyle and a new model of wealth

The sixth fallacy: green growth and efficiency gains are sufficient reasons to economically implement the concept of sustainability.

Sustainability does not only mean a socio-technical programme to save resources; more than anything else, it means a new ethical-cultural orientation. Current paradigms of progress and unlimited growth must be replaced by the guiding principle of development, which is embedded in the metabolic cycles and rhythms of nature. Sustainability also implies a new definition of limits and goals for progress. Instead of ‘faster, higher, farther’, safeguarding the ecological, social and economic stability of human living spaces will be a central principle.

The considered avoidance of risk is another principle for societal development and political planning. Thus, reflection is required on certain issues of liberalism. However, alternative (post-growth) models also raise many unanswered questions (Sachverständigengruppe ‘Weltwirtschaft und Sozialethik’, 2018 ). Sustainability must be described in terms of criteria for what should grow and what should decrease. Furthermore, these criteria require standards (for a discussion of controversial economic and scientific theories, see: Miegel, Reference Miegel 2010 ; Hauff, Reference Hauff 2012 ; Linz, Reference Linz 2014 ).

The blind spot in traditional growth concepts is that growth is equated unilaterally with an increase in prosperity. However, the gross national product is also increased by accidents, although these can hardly be counted as profit. A common misconception of sustainable growth, linked to social theory, is that qualitative standards for and definitions of a good life are regarded as private matters and are thus excluded from public and scientific discourse. The win–win promises, which focus on decoupling growth and environmental consumption, have not proved their worth. Successes in individual areas, for instance, have been neutralized or reversed by the so-called ‘rebound effect’ of rising demand for prosperity. In other words, efficiency gains are neutralized due to rising prosperity (von Weizsäcker, Hargroves & Smith, Reference von Weizsäcker, Hargroves and Smith 2010 ; Sachverständigengruppe ‘Weltwirtschaft und Sozialethik’, 2018 ).

Sustainability therefore also requires a systemic and anchored ability for people to become self-sufficient (thrifty) and efficient (technologically optimized). In addition, sustainability requires the substitution of resources. Being able to link innovative technology with organizational optimization and changes in personal attitudes is essential.

A culture of sustainability acknowledges the protection of nature as a cultural task. Such a culture also integrates the quality of the environment as a fundamental value in definitions of wealth – at the cultural, social, health-related, political and economic levels. Sustainable culture expresses a rediscovery of the ethics of moderate living. A sustainable lifestyle does not forego wealth but rather aims to achieve intelligent, resource-friendly and environment-friendly patterns of consumption (Stehr, Reference Stehr 2007 ). Nevertheless, the opportunity for critical consumerism is rather small. In her book Ende der Märchenstunde , Katharina Hartmann drew a sobering picture of the power of a moralization of the markets through eco-social customer demand (Hartmann, Reference Hartmann 2009 ).

7. Theological dimension: belief in creation and sustainability

The seventh fallacy: religions, especially Christianity, do not play a major role in shaping the concept of sustainability and bringing it to life.

The distinct quality of Christian ethics in a pluralistic society is not derived mainly from additional arguments for sustainable actions. It lies, rather, in incorporating a spiritual dimension that inspires and motivates ethical behaviour. Christian ethics draw on a rich tradition that aims to translate ethics into an ethos by addressing both hearts and minds, and both deep-seated hopes and daily life.

The Brazilian theologian and writer Leonardo Boff criticized the anthropological and ethical traditions of modernity for not moving beyond rationality. Boff stated that ‘Without mysticism and its institutionalization in the different religions, ethics would degenerate to a cold catalogue of regulations and the codes of ethics would become processes of social control and cultural paternalism’ (Boff, Reference Boff 2000 , p. 11).

Spirituality is a type of knowledge that draws attention to the connection between ideas and emotions. It enables us to understand the manifold qualities of nature – beyond their physical, quantifiable features. Many environmentalists insist on an intrinsic value of nature. This requires a perspective that endorses not only the factual and scientifically quantifiable reality but also the beauty of nature, its sense and symbolism. It requires an aesthetic and spiritual sensibility that does not see things in isolation but in their entirety and their relationships. This is how ecological and religious perceptions can enhance and complement each other.

Responsibility for nature during climate change, the rising number of human beings on Earth, and the scarcity of resources are not a problem of knowledge. The problem is one of conviction and belief: we know about climate change and environmental issues, but it also seems that we do not really know; we do not understand, in a deeper sense, what the scientific data are telling us. We cannot sufficiently imagine what the data mean for us and for people all over the world – or for life on Earth in general. Therefore, we are unable to react adequately. We have never experienced such a deep, complex change of living conditions. The consequences seem too obscure for most westerners and for wealthy people globally. Pope Francis, in the encyclical Laudato si’, called this a ‘lack of sense for reality’ because of a ‘lack of physical contact’ with nature and with people who are suffering (Pope Francis, 2015 , p. 49).

One of the deepest aspects of spirituality presented in Laudato si’ is a balance between realistic and critical awareness of the situation of ecological destruction, and of the social problems connected with it – as well as the positive attitude of hope. The Christian holy scripture is called εὐαγγέλιον, the ‘good message’. That means a Christian's task is to spread hope, not anxiety. Important in this context is the cultural understanding of life and human identity and the practice of solidarity. The ecological crisis raises religious questions. It requires us to understand the greater cultural, anthropological and ethical contexts in which human lives are embedded.

The religious potential lies in spiritual orientation, long-term ethics, the forming of a global community, ritual endowment of life with meaning and institutional anchoring. A belief in God's creation highlights the limits of humankind with a certain humility and modesty. So far, these qualities have been activated only minimally. In other words, the discourse on sustainability is productive for religion to the extent that it raises basic issues about the world's long-term future, and about global responsibility.

Sustainability is the missing link between a belief in creation and modern environmental discourses. The Christian idea of charity was, for many centuries, understood merely as a personal virtue; the idea became politically effective and relevant only when connected to the solidarity principle. Similarly, the belief in creation needs translation into categories at the level of social order so that it can become a politically viable and justifiable idea. Belief in creation, without sustainability, is – in terms of structural and political ethics – a form of blindness. Sustainability without the belief in creation, whether Christian or not, risks ethical shallowness (Vogt, Reference Vogt 2013 ).

If we assume, in line with leading sociologists (Lübbe, Reference Lübbe, Graevenitz and Marqurd 1998 ; Luhmann, Reference Luhmann 2000 ), that managing contingency (in the meaning described above) is a main function of religion, then the competence of theological ethics in the discourse on sustainability becomes evident. Managing contingency is vital to respond to the postmodern breakdown of the belief in progress, which is the starting point of debates on climate change and sustainability. We do not need to resort to ecological apocalyptic scenarios or to a new version of the utopia of permanent growth. The religious dimension of hope liberates us from blind belief in the political promise of a complete management of all problems of ecology and social life.

The seven theses that have been briefly presented here leave questions unanswered and require deeper discussion. We did not want to offer limited definitions, but rather to stimulate debate about rehabilitating the ‘sustainability concept’.

Author ORCIDs

Christoph Weber, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9111-3339

Acknowledgments

Author contributions.

Markus Vogt and Christoph Weber conceived and designed the study. They wrote the article together.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. But Christoph Weber holds a PhD scholarship by the Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung e.V. which supports his work for his doctor's thesis.

Conflict of interest

Publishing ethics.

This research and article complies with Global Sustainability's publishing ethics guidelines.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Markus Vogt (a1) and Christoph Weber (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2019.1

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Accident and Trauma

- Anaesthesia

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Critical Care/Intensive Care/Emergency Medicine