The action of “Antigone” follows on from the Theban civil war , in which the two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices , died fighting each other for the throne of Thebes after Eteocles had refused to give up the crown to his brother as their father Oedipus had prescribed. Creon , the new ruler of Thebes, has declared that Eteocles is to be honoured and Polynices is to be disgraced by leaving his body unburied on the battlefield (a harsh and shameful punishment at the time). As the play begins , Antigone vows to bury her brother Polynices ‘ body in defiance of Creon ‘s edict, although her sister Ismene refuses to help her, fearing the death penalty. Creon , with the support of the Chorus of elders, repeats his edict regarding the disposal of Polynices ‘ body, but a fearful sentry enters to report that Antigone has in fact buried her brother’s body. Creon , furious at this wilful disobedience, questions Antigone over her actions, but she does not deny what she has done and argues unflinchingly with Creon about the morality of his edict and the morality of her deeds. Despite her innocence, Ismene is also summoned and interrogated and tries to confess falsely to the crime, wishing to die alongside her sister, but Antigone insists on shouldering full responsibility.  Creon ‘s son , Haemon , who is betrothed to Antigone , pledges allegiance to his father’s will but then gently tries to persuade his father to spare Antigone . The two men are soon bitterly insulting each other and eventually Haemon storms out, vowing never to see Creon again. Creon decides to spare Ismene but rules that Antigone should be buried alive in a cave as punishment for her transgressions. She is brought out of the house, bewailing her fate but still vigorously defending her actions, and is taken away to her living tomb, to expressions of great sorrow by the Chorus. The blind prophet Tiresias warns Creon that the gods side with Antigone , and that Creon will lose a child for his crimes of leaving Polynices unburied and for punishing Antigone so harshly. Tiresias warns that all of Greece will despise him, and that the sacrificial offerings of Thebes will not be accepted by the gods, but Creon merely dismisses him as a corrupt old fool. However, the terrified Chorus beg Creon to reconsider, and eventually he consents to follow their advice and to free Antigone and to bury Polynices . Creon , shaken now by the prophet’s warnings and by the implications of his own actions, is contrite and looks to right his previous mistakes.  Creon now blames himself for everything that has happened and he staggers away, a broken man. The order and rule of law he values so much has been protected, but he has acted against the gods and has lost his child and his wife as a result. The Chorus closes the play with an attempt at consolation , by saying that although the gods punish the proud, punishment also brings wisdom. Although set in the city-state of Thebes about a generation before the Trojan War (many centuries before Sophocles ’ time), the play was actually written in Athens during the rule of Pericles. It was a time of great national fervor, and Sophocles himself was appointed as one of the ten generals to lead a military expedition against Samos Island shortly after the play’s release. Given this background, it is striking that the play contains absolutely no political propaganda or contemporary allusions or references to Athens, and indeed betrays no patriotic interests whatsoever. All the scenes take place in front of the royal palace at Thebes (conforming to the traditional dramatic principle of unity of place) and the events unfold in little more than twenty-four hours. A mood of uncertainty prevails in Thebes in the period of uneasy calm following the Theban civil war and, as the debate between the two central figures advances, the elements of foreboding and impending doom predominate in the atmosphere. The series of deaths at the end of the play, however, leaves a final impression of catharsis and an emptying of all emotion, with all passions spent. The idealistic character of Antigone consciously risks her life through her actions, concerned only with obeying the laws of the gods and the dictates of familial loyalty and social decency. Creon , on the other hand, regards only the requirement of political expediency and physical power, although he too is unrelenting in his stance. Much of the tragedy lies in the fact that Creon ’s realization of his folly and rashness comes too late, and he pays a heavy price, left alone in his wretchedness.  It explores themes such as state control (the right of the individual to reject society’s infringement on personal freedoms and obligations); natural law vs. man-made law ( Creon advocates obedience to man-made laws, while Antigone stresses the higher laws of duty to the gods and one’s family) and the related issue of civil disobedience ( Antigone believes that state law is not absolute, and that civil disobedience is justified in extreme cases); citizenship ( Creon ‘s decree that Polynices should remain unburied suggests that Polynices ’ treason in attacking the city effectively revokes his citizenship and the rights that go with it – ”citizenship by law” rather than “citizenship by nature”); and family (for Antigone , the honour of the family outweighs her duties to the state). Much critical debate has centred on why Antigone felt such a strong need to bury Polynices a second time in the play , when the initial pouring of dust over her brother’s body would have fulfilled her religious obligations. Some have argued that this was merely a dramatic convenience of Sophocles , while others maintain that it was a result of Antigone ’s distracted state and obsessiveness. In the mid-20th Century, the Frenchman Jean Anouilh wrote a well-regarded version of the play, also called “Antigone” , which was deliberately ambiguous regarding the rejection or acceptance of authority, as befitted its production in occupied France under Nazi censorship. - English translation by R. C. Jeb (Internet Classics Archive): http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/antigone.html

- Greek version with word-by-word translation (Perseus Project): http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0185

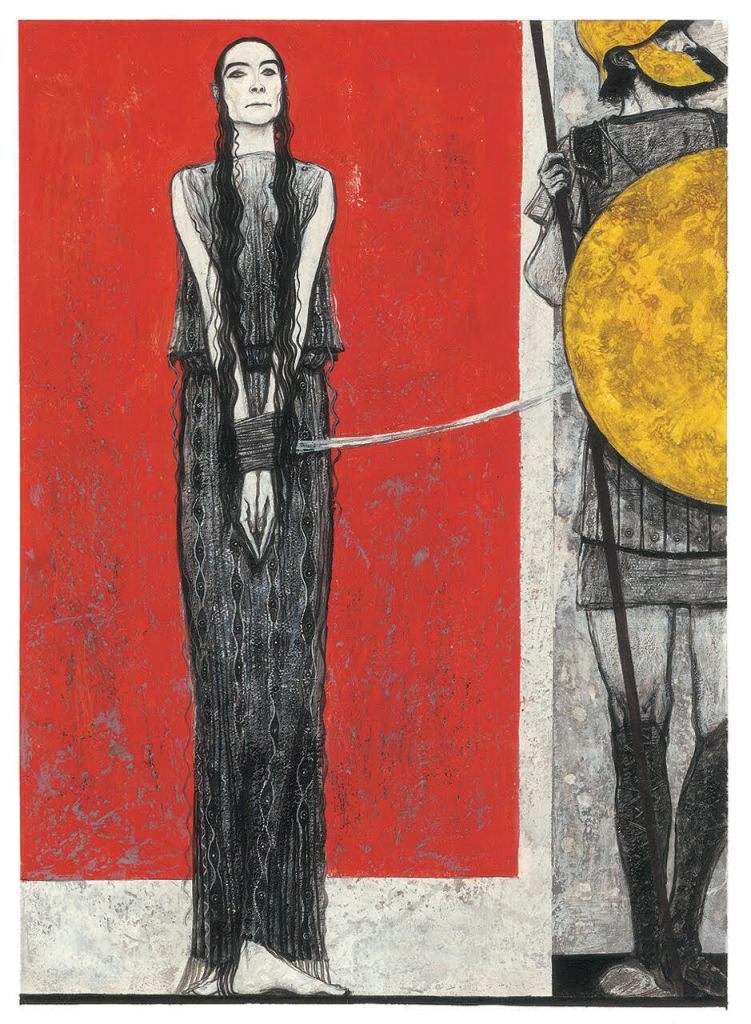

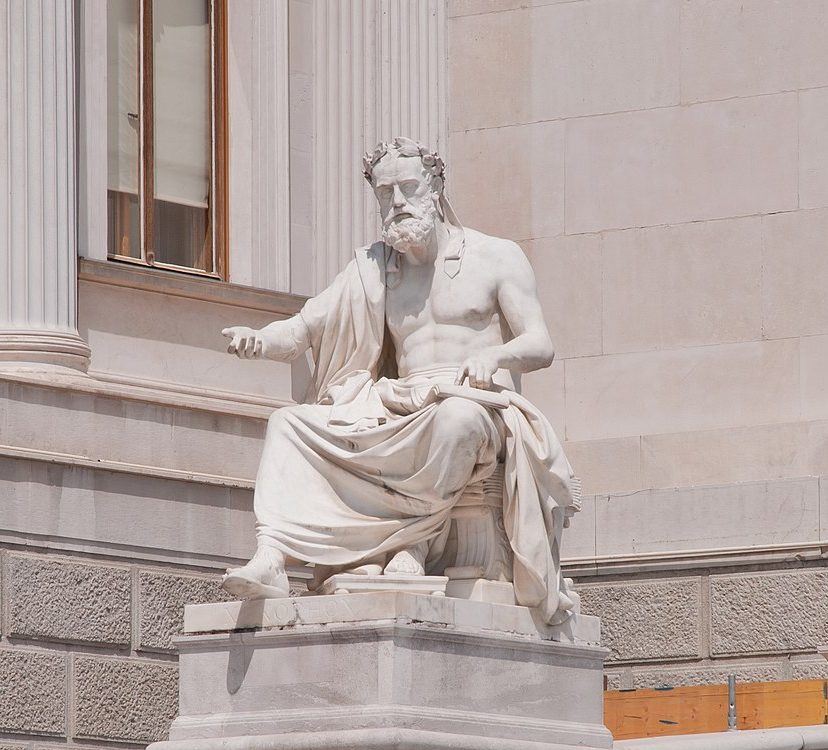

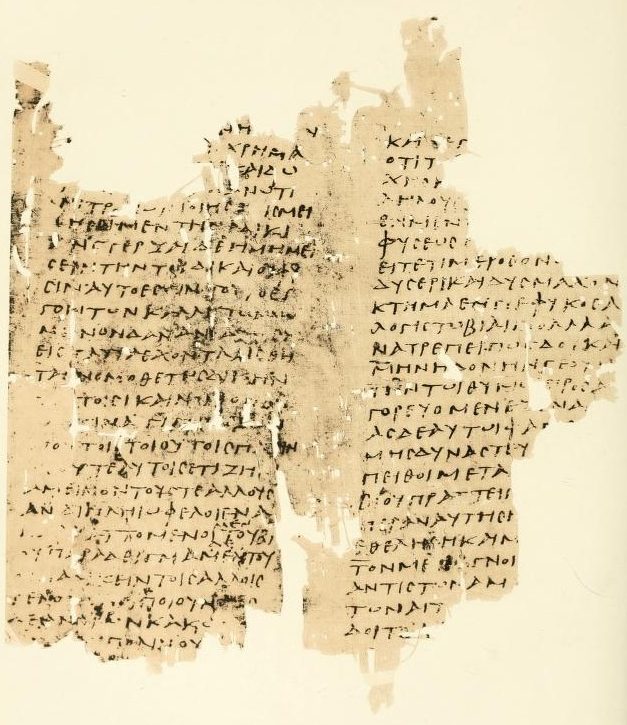

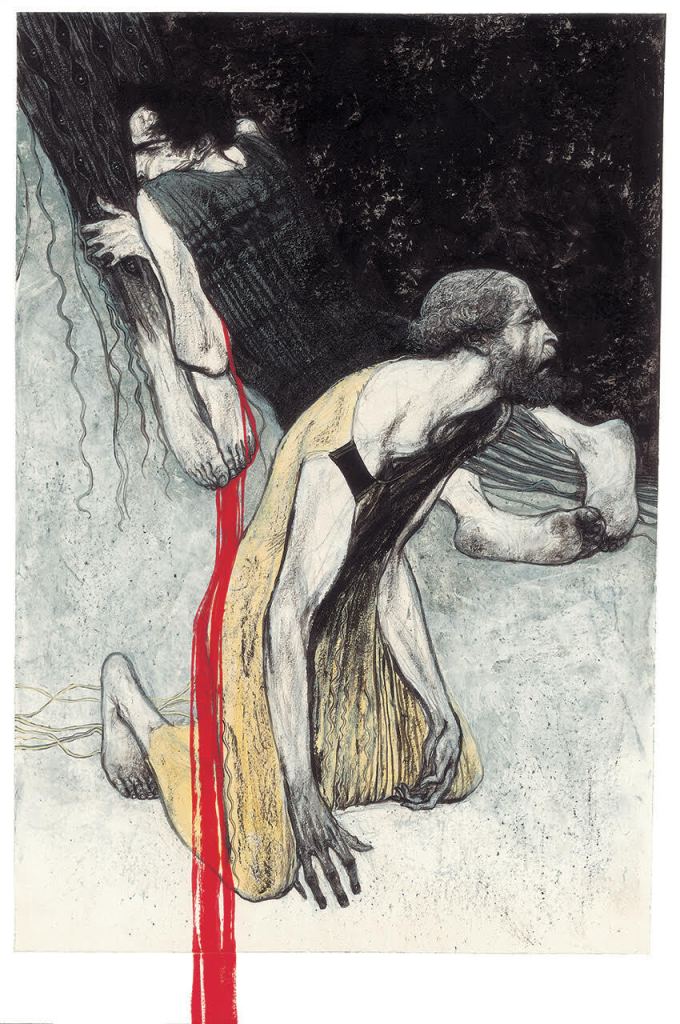

[rating_form id=”1″]  Literary Theory and CriticismHome › Drama Criticism › Analysis of Sophocles’ Antigone Analysis of Sophocles’ AntigoneBy NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 29, 2020 • ( 0 ) Within this single drama—in great part, a harsh critique of Athenian society and the Greek city-state in general—Sophocles tells of the eternal struggle between the state and the individual, human and natural law, and the enormous gulf between what we attempt here on earth and what fate has in store for us all. In this magnificent dramatic work, almost incidentally so, we find nearly every reason why we are now what we are. —Victor D. Hanson and John Heath, Who Killed Homer? The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom With Antigone Sophocles forcibly demonstrates that the power of tragedy derives not from the conflict between right and wrong but from the confrontation between right and right. As the play opens the succession battle between the sons of Oedipus—Polynices and Eteocles—over control of Thebes has resulted in both of their deaths. Their uncle Creon, who has now assumed the throne, asserts his authority to end a destructive civil war and decrees that only Eteocles, the city’s defender, should receive honorable burial. Polynices, who has led a foreign army against Thebes, is branded a traitor. His corpse is to be left on the battlefield “to be chewed up by birds and dogs and violated,” with death the penalty for anyone who attempts to bury him and supply the rites necessary for the dead to reach the underworld. Antigone, Polynices’ sister, is determined to defy Creon’s order, setting in motion a tragic collision between opposed laws and duties: between natural and divine commands that dictate the burial of the dead and the secular edicts of a ruler determined to restore civic order, between family allegiance and private conscience and public duty and the rule of law that restricts personal liberty for the common good. Like the proverbial immovable object meeting an irresistible force, Antigone arranges the impact of seemingly irreconcilable conceptions of rights and responsibilities, producing one of drama’s enduring illuminations of human nature and the human condition.  Antigone is one of Sophocles’ greatest achievements and one of the most influential dramas ever staged. “Between 1790 and 1905,” critic George Steiner reports, “it was widely held by European poets, philosophers, [and] scholars that Sophocles’ Antigone was not only the fi nest of Greek tragedies, but a work of art nearer to perfection than any other produced by the human spirit.” Its theme of the opposition between the individual and authority has resonated through the centuries, with numerous playwrights, most notably Jean Anouilh, Bertolt Brecht, and Athol Fugard grafting contemporary concerns and values onto the moral and political dramatic framework that Sophocles established. The play has elicited paradoxical responses reflecting changing cultural and moral imperatives. Antigone, who has been described as “the first heroine of Western drama,” has been interpreted both as a heroic martyr to conscience and as a willfully stubborn fanatic who causes her own death and that of two other innocent people, forsaking her duty to the living on behalf of the dead. Creon has similarly divided critics between censure and sympathy. Despite the play’s title, some have suggested that the tragedy is Creon’s, not Antigone’s, and it is his abuse of authority and his violations of personal, family, and divine obligations that center the drama’s tragedy. The brilliance of Sophocles’ play rests in the complexity of motive and the competing absolute claims that the drama displays. As novelist George Eliot observed, It is a very superficial criticism which interprets the character of Creon as that of hypocritical tyrant, and regards Antigone as a blameless victim. Coarse contrasts like this are not the materials handled by great dramatists. The exquisite art of Sophocles is shown in the touches by which he makes us feel that Creon, as well as Antigone, is contending for what he believes to be the right, while both are also conscious that, in following out one principle, they are laying themselves open to just blame for transgressing another. Eliot would call the play’s focus the “antagonism of valid principles,” demonstrating a point of universal significance that “Wherever the strength of a man’s intellect, or moral sense, or affection brings him into opposition with the rules which society has sanctioned, there is renewed conflict between Antigone and Creon; such a man must not only dare to be right, he must also dare to be wrong—to shake faith, to wound friendship, perhaps, to hem in his own powers.” Sophocles’ Antigone is less a play about the pathetic end of a victim of tyranny or the corruption of authority than about the inevitable cost and con-sequence between competing imperatives that define the human condition. From opposite and opposed positions, both Antigone and Creon ultimately meet at the shared suffering each has caused. They have destroyed each other and themselves by who they are and what they believe. They are both right and wrong in a world that lacks moral certainty and simple choices. The Chorus summarizes what Antigone will vividly enact: “The powerful words of the proud are paid in full with mighty blows of fate, and at long last those blows will teach us wisdom.” As the play opens Antigone declares her intention to her sister Ismene to defy Creon’s impious and inhumane order and enlists her sister’s aid to bury their brother. Ismene responds that as women they must not oppose the will of men or the authority of the city and invite death. Ismene’s timidity and deference underscores Antigone’s courage and defiance. Antigone asserts a greater allegiance to blood kinship and divine law declaring that the burial is a “holy crime,” justified even by death. Ismene responds by calling her sister “a lover of the impossible,” an accurate description of the tragic hero, who, according to scholar Bernard Knox, is Sophocles’ most important contribution to drama: “Sophocles presents us for the first time with what we recognize as a ‘tragic hero’: one who, unsupported by the gods and in the face of human opposition, makes a decision which springs from the deepest layer of his individual nature, his physis , and then blindly, ferociously, heroically maintains that decision even to the point of self-destruction.” Antigone exactly conforms to Knox’s description, choosing her conception of duty over sensible self-preservation and gender-prescribed submission to male authority, turning on her sister and all who oppose her. Certain in her decision and self-sufficient, Antigone rejects both her sister’s practical advice and kinship. Ironically Antigone denies to her sister, when Ismene resists her will, the same blood kinship that claims Antigone’s supreme allegiance in burying her brother. For Antigone the demands of the dead overpower duty to the living, and she does not hesitate in claiming both to know and act for the divine will. As critic Gilbert Norwood observes, “It is Antigone’s splendid though perverse valor which creates the drama.” Before the apprehended Antigone, who has been taken in the act of scattering dust on her brother’s corpse, lamenting, and pouring libations, is brought before Creon and the dramatic crux of the play, the Chorus of The-ban elders delivers what has been called the fi nest song in all Greek tragedy, the so-called Ode to Man, that begins “Wonders are many, and none is more wonderful than man.” This magnificent celebration of human power over nature and resourcefulness in reason and invention ends with a stark recognition of humanity’s ultimate helplessness—“Only against Death shall he call for aid in vain.” Death will test the resolve and principles of both Antigone and Creon, while, as critic Edouard Schuré asserts, “It brings before us the most extraordinary psychological evolution that has ever been represented on stage.” When Antigone is brought in judgment before Creon, obstinacy meets its match. Both stand on principle, but both reveal the human source of their actions. Creon betrays himself as a paranoid autocrat; Antigone as an individual whose powerful hatred outstrips her capacity for love. She defiantly and proudly admits that she is guilty of disobeying Creon’s decree and that he has no power to override divine law. Nor does Antigone concede any mitigation of her personal obligation in the competing claims of a niece, a sister, or a citizen. Creon is maddened by what he perceives to be Antigone’s insolence in justifying her crime by diminishing his authority, provoking him to ignore all moderating claims of family, natural, or divine extenuation. When Ismene is brought in as a co-conspirator, she accepts her share of guilt in solidarity with her sister, but again Antigone spurns her, calling her “a friend who loves in words,” denying Ismene’s selfless act of loyalty and sympathy with a cold dismissal and self-sufficiency, stating, “Never share my dying, / don’t lay claim to what you never touched.” However, Ismene raises the ante for both Antigone and Creon by asking her uncle whether by condemning Antigone he will kill his own son’s betrothed. Creon remains adamant, and his judgment on Antigone and Ismene, along with his subsequent argument with his son, Haemon, reveals that Creon’s principles are self-centered, contradictory, and compromised by his own pride, fears, and anxieties. Antigone’s challenge to his authority, coming from a woman, is demeaning. If she goes free in defiance of his authority, Creon declares, “I am not the man, she is.” To the urging of Haemon that Creon should show mercy, tempering his judgment to the will of Theban opinion that sympathizes with Antigone, Creon asserts that he cares nothing for the will of the town, whose welfare Creon’s original edict against Polynices was meant to serve. Creon, moreover, resents being schooled in expediency by his son. Inflamed by his son’s advocacy on behalf of Antigone, Creon brands Haemon a “woman’s slave,” and after vacillating between stoning Antigone and executing her and her sister in front of Haemon, Creon rules that Antigone alone is to perish by being buried alive. Having begun the drama with a decree that a dead man should remain unburied, Creon reverses himself, ironically, by ordering the premature burial of a living woman. Antigone, being led to her entombment, is shown stripped of her former confidence and defiance, searching for the justification that can steel her acceptance of the fate that her actions have caused. Contemplating her living descent into the underworld and the death that awaits her, Antigone regrets dying without marriage and children. Gone is her reliance on divine and natural law to justify her act as she equivocates to find the emotional source to sustain her. A husband and children could be replaced, she rationalizes, but since her mother and father are dead, no brother can ever replace Polynices. Antigone’s tortured logic here, so different from the former woman of principle, has been rejected by some editors as spurious. Others have judged this emotionally wrought speech essential for humanizing Antigone, revealing her capacity to suffer and her painful search for some consolation.  The drama concludes with the emphasis shifted back to Creon and the consequences of his judgment. The blind prophet Teiresias comes to warn Creon that Polynices’ unburied body has offended the gods and that Creon is responsible for the sickness that has descended on Thebes. Creon has kept from Hades one who belongs there and is sending to Hades another who does not. The gods confirm the rightness of Antigone’s action, but justice evades the working out of the drama’s climax. The release of Antigone comes too late; she has hung herself. Haemon commits suicide, and Eurydice, Creon’s wife, kills herself after cursing Creon for the death of their son. Having denied the obligation of family, Creon loses his own. Creon’s rule, marked by ignoring or transgressing cosmic and family law, is shown as ultimately inadequate and destructive. Creon is made to realize that he has been rash and foolish, that “Whatever I have touched has come to nothing.” Both Creon and Antigone have been pushed to terrifying ends in which what truly matters to both are made starkly clear. Antigone’s moral imperatives have been affirmed but also their immense cost in suffering has been exposed. Antigone explores a fundamental rift between public and private worlds. The central opposition in the play between Antigone and Creon, between duty to self and duty to state, dramatizes critical antimonies in the human condition. Sophocles’ genius is his resistance of easy and consoling simplifications to resolve the oppositions. Both sides are ultimately tested; both reveal the potential for greatness and destruction. 24 lectures on Greek Tragedy by Dr. Elizabeth Vandiver. Share this:Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature Tags: Analysis of Sophocles’ Antigone , Antigone Analysis , Antigone Criticism , Antigone Essay , Antigone Guide , Antigone Lecture , Antigone PDF , Antigone Summary , Antigone Themes , Bibliography of Sophocles’ Antigone , Character Study of Sophocles’ Antigone , Criticism of Sophocles’ Antigone , Drama Criticism , Essays of Sophocles’ Antigone , Greek Tragedy , Literary Criticism , Notes of Sophocles’ Antigone , Plot of Sophocles’ Antigone , Simple Analysis of Sophocles’ Antigone , Study Guides of Sophocles’ Antigone , Summary of Sophocles’ Antigone , Synopsis of Sophocles’ Antigone , Themes of Sophocles’ Antigone , Tragedy Related Articles Leave a Reply Cancel replyYou must be logged in to post a comment.  Department of Greek & Latin Antigone Study Guide Sophocles (c. 497/6- 406/5 BC) is, along with Aeschylus and Euripides, one of the three ancient Greek tragic playwrights by whom complete plays survive. He won at least twenty victories in the tragic competitions, and never came third (last), a feat which suggests that he was the most successful of the three. Seven complete plays of his survive, of which Antigone and Oedipus Tyrannus are the most well-known and frequently performed. The following three essays explore the play's themes and context. Sophocles' Antigone in Context by Professor Chris CareyGreek tragedy is a remarkable fictional creation. We are used to a theatre which can embrace past and present, fictitious and historical, bizarre fantasy and mundane reality. The Athenian theatre was far more limited than this. Like virtually all Greek poetry at all periods in antiquity, its subject matter was heroic myth. Invented plots with fictitious people and events were very few (and not found before the late fifth century). Historical tragedy (the staple of theatre from Shakespeare to the present) again was very rare. With very few exceptions, tragedy was about heroes. For Greeks at any period, the world of the heroes meant the world which they met in epic poetry, and especially Homer, the ultimate Greek classic. Because we are so used to Greek tragedy, we don't usually stop to notice how strange all this is. The heroes are members of a superior elite. And the epic world is always ruled by kings. It has assemblies, and they matter; but they don't have power. Hereditary monarchy had become a rarity in Greece long before the rise of tragedy. So the epic world was politically remote. In fact, of all Greek states in the classical period, Athens was probably the furthest removed from the political world of epic. In democratic Athens public policy and legislation were in the hands of the mass assembly. Yet for two hundred years and more mass audiences sat in the theatre of Dionysus and watched plays about kings sponsored by the democratic state. The issue is of course more complicated than this. Firstly, the world of the epic was a very familiar world to the Athenian audience. Epic poetry was performed every year at the civic festivals, which meant that the heroic age was a shared possession for the vast audience in the Athenian theatre, not just the property of an educated elite. Secondly, the world inside the plays and the world in which the audience lived were engaged in a complex and shifting relationship. In any attempt to represent or even to understand the past, the present acts as frame which shapes presentation or perception; we may or may not be aware of it, but it is always there. Literature which deals with the past therefore has a foot in two worlds. This includes Greek tragedy. Tragedy is riddled with anachronisms, on politics, gender, ethnicity, status, even technology (people in tragedy write letters and suicide notes, for instance, while in the epic world writing is completely absent except for one very mysterious passage in Homer's Iliad ). The effect is to make the tragic world a middle space where heroic past and present meet. This makes the tragic stage an ideal space to explore political issues of interest to democratic Athens. Not all tragedy is political and not all of the political questions are unique either to Athens or to democracy. But Athens (with rare exceptions) was unusual among the classical Greek states in its openness to dispute and dissent and Athenian drama is almost unique in Greek literature in its ability to explore areas of actual or potential political tension. This is true in the case of Antigone . Anyone in the audience listening to the newly appointed regent Creon might well catch echoes of contemporary sentiments about loyalty to the city. The rhetoric of devotion to the city above all else and at any cost which Sophocles puts in his mouth sounds very like the rhetoric of the democratic statesman Pericles in the historian Thucydides (Pericles even goes so far as to claim that we should all be lovers of the city). The sentiment has a powerful appeal. This was a world of citizen soldiers and a citizen was expected to fight and if necessary die for the city. As Creon says: 'This land - our land - is the ship that preserves us and it is on this ship that we sail straight and as she prospers, so will we.' But his insistence on loyalty to the state to the exclusion of all other allegiance prolongs into the present the rifts of the past and proves disastrous for the next generation of the family and robs him of his family. The issue of burial which forms the focus for conflict in this play had political echoes. Burial was a vitally important aspect both of family and of civic life. For the city it was a means both of honouring devotion and also of punishing disloyalty. The world of this play is not just postwar but post-civil-war. The dead Polynices came with a foreign army to take his home city by force and died in the attempt. In Sophocles' Athens anyone executed for treason could not be buried in Attica. So some features of the play probably sounded very familiar. Democratic Athens demanded a lot of its citizens and at the probable date of Antigone this was visible especially in the treatment of the dead. As far as we know Athens monopolized its war dead to a degree unmatched by any other Greek state. Where most Greek states simply buried their dead on the battlefield, Athenian practice was to collect and burn the dead and bring the bones home. They then held a state funeral and buried the war dead in communal state graves (excavations for the new Athens metro unearthed one such burial just a decade ago) with no designation of family, just the name of their tribe. The war dead are now the property of the city. At the same time private grave memorials almost disappear. It looks as though only public burials, and specifically those for the dead warriors, matter. But by tradition the family not only buried its dead but also made offerings every year at the family tombs; and the job of preparing the dead and the lead in mourning fell to the women. By the late fifth century the private memorials, including memorials for those who died in war, become more common, and it looks as though the tensions between the demands of the state and the needs of the family have been resolved. But tensions there probably were and death and burial was one of the key areas. Issues such as family or individual versus state are Greek issues as well as Athenian issues. But they were probably present in Athens to an unusual degree and were at their most visible at the time Antigone was performed in the late 440s. Antigone is not about Athens' burial of the war dead. And it is not about contemporary democratic ideology. It is a story about a clash of wills, a clash of principles and a clash of loyalties. About power and its limits and legitimacy. About commitment, tenacity and integrity. And it is not a sermon. It throws up more questions than it answers. It could play in any theatre of the Greek world, as it has played in countless theatres in many languages since. But for its Athenian audience the echoes of contemporary areas of tension gave it an added intensity. Questions and Activities: - How would the experiences of ancient Greek theatrical audiences have differed from those of modern ones? How might that affect our appreciation of Sophocles' Antigone ?

- If you were to translate the basic story of the play into modern Britain, what aspects would you change, what would you retain, and why?

- What difference would it make if Antigone were staged in a contemporary setting, rather than the distant past?

Antigone and Creon in Conflict by Dr. Dimitra KokkiniAntigone is a play full of intensity. Audience (and scholarly) responses have always been conflicted when it comes to analysing both characters' arguments. For some, secular law and rationality, as expressed by Creon, are right, while Antigone's religious approach is to be rejected as irrational. For others, Antigone's argument is the only one with validity. The remaining views recognise various degrees of legitimacy in both arguments, eventually proving the impossibility of the task in discerning right from wrong in this conflict. Despite the fact that this explosive clash highlights the vast differences between Creon and Antigone in terms of world views and loyalties, it also brings to the fore their similarities in terms of characterisation. Creon continuously asserts his power, both in terms of social and gender status; he is the ruler of the city, in fact, its defender in what is seen an unlawful attack by Polyneices against his own fatherland (the gravest of sins in civic terms). Moreover, he is a man, faced with an insubordinate, stubborn, powerless female who is also a member of his own family and under his jurisdiction and protection. Antigone, on the other hand, continuously asserts the validity on her argument in religious and moral terms, being, at the same time, constantly aware of her limitations due to her gender and position in the city and her own family. Yet, although they both take pains to highlight the unbridgeable gap between them, contrasting civic/rational (Creon) and family/religious (Antigone) duty, they are remarkably similar in the way they approach and respond to one another. Both are characterised by unyielding stubbornness, a deep belief in the rightness of their own value system, and complete failure in identifying any validity whatsoever in each other's argument. Both insist on upholding their respective values with obstinate determination to the end: Antigone dies unchanged, whereas Creon's change of heart comes too late having first caused the destruction of his entire family. More importantly, neither of them are easily relatable - or indeed sympathetic - characters. Antigone is often too self-righteous, obsessed with honouring Polyneices at all costs. She is dismissive of Ismene, almost indifferent to her betrothed, Haemon. Creon is equally obsessed with administering what he perceives as justice, as well as upholding his law and punishing the offender, he is cruel and dismissive towards his son. It is easier for us, the audience, to identify with Ismene, Eurydice or Haemon. Ismene, a foil for Antigone and her exact opposite, is arguably less determined and daring than her sister; but she is also much closer to an everyday person, aware of her limitations and hesitant to challenge authority and the laws imposed by a ruler. Antigone may be admirable for her bravery and resolution, but she is also extraordinarily distant to ordinary human beings. Although she presents herself as a weak woman and speaks of all the typical female experiences she will be missing with her untimely death, she functions more like a symbol - some say she is almost genderless. Ismene, however, appears to be more human, displaying a more conventional kind of femininity, which renders her pitiful but also more relatable as a character. In a similar way, we feel more pity and sympathy for Haemon than we do for the two protagonists. His attachment to her is evident in a rare tragic instance of a young man being in love, but it is hardly reciprocated. Antigone's fixation on honouring Polyneices leaves little room for the development of any other relationship. Haemon fights, unsuccessfully, with his father in an attempt to save his betrothed and, when this fails due to Creon's refusal to repeal his decision, his response is rash and emotional. This is a young man in love, who is denied his chance to be with his beloved and, on seeing her dead decides to take his own life out of grief. In contrast with Antigone, whose suicide is consistent with her characterisation throughout the play and is directly related to her immovable value system, Haemon's suicide is full of pathos and his motivation feels more easily understandable in terms of personal relationships and youthful desperation. His death functions as the trigger for Eurydice's suicide, the culmination of Creon's catastrophic decisions and Antigone's unyielding position. Her appearance on stage is limited to one scene, with her uttering one single question to the Messenger before departing in silence, ominously, after the death of her son is confirmed, never to reappear on stage. Antigone and Creon are caught in an impossible circle of stubbornness, miscommunication and destruction. Together, they manage to cause utter grief and ruin for their family caught in a conflict of ever-increasing intensity as they pull further and further apart. Antigone's death and Creon's remorse cause pity and reveal the utter futility of their conflict at the end of the tragedy; but the fate of the other characters, the innocent bystanders entangled in this mighty clash of wills, beg for our sympathy and compassion as much as the protagonists, if not more. 1. Which character from the play do you sympathise with the most and why? 2. 'Creon and Antigone are more similar than different to one another'. To what extent do you agree with this claim? 3. To what extent must tragedy always depend on conflict? Conflict and Contrast in Sophocles' Antigone by Dr. Tom MackenziePerhaps more than any other Greek tragedy, Sophocles' Antigone has captured the interests of philosophers, ranging from Aristotle (fourth century BC) to Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and beyond. Most famously, the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) saw the tragedy as depicting, at its core, a conflict between the abstract principles of the household (the oikos) and the state (the polis), embodied in the characters of Antigone and Creon respectively. When we come to watch the play, it is not hard to see why this interpretation has proven immensely influential. On a purely formal level, the two characters dominate the action more than any of the others. It is their decisions - Creon's to impose the sanction against burying Polyneices, and Antigone's to bury him nonetheless - that cause the events of the narrative. Antigone is the eponymous heroine whose initial speech opens the play, whilst Creon receives more lines than any other character and is the exclusive focus of our attention after Antigone's departure in the latter part of the tragedy. The two characters thus bookend the action onstage, a structuring device that seems to illustrate the contrast between them. It is sometimes claimed that Greek tragedy typically focusses on a single character, but if that is the case, then Antigone is an exception to this tendency, for Creon and Antigone appear to be of equal concern. Many aspects of the play can be taken to suggest that the two characters are indeed representative of certain contrasting principles. Perhaps the most obvious contrast is that between male and female: Ismene initially opposes Antigone's act of defiance partly on the grounds that they are women, and so 'cannot fight against men'. Creon further emphasizes the gender division in claiming that Antigone will be 'the man' and not him, if she is to challenge his authority with impunity. Several other statements of his also betray this anxiety. Antigone's defiance of her uncle, her closest living male relative, markedly transcends the normal behaviour expected of women in fifth-century Athens, a notoriously patriarchal society with severe restrictions on the freedom of women. The contrast in genders also evokes wider political and cosmic polarities: women's influence was supposed to be restricted to the oikos, whilst Athenian politics was exclusively a male activity: the welfare of the city was thought to be the responsibility of free males alone. Antigone's act is one of loyalty towards a close relative, a member of her oikos - but it is seen by Creon as an act against the interests of the state. His edict was pronounced in order to protect Thebes, and he explicitly criticises anyone who 'values a loved one greater than his city', a statement which inevitably recalls Antigone's defiance. Indeed, part of this initial speech was quoted by the fourth-century Athenian orator Demosthenes as a positive, patriotic sentiment, a fact which may suggest that Creon, at least at this point in the play, could be taken to embody civic values. Yet Antigone herself does not see the conflict as one between the oikos and the polis so much as one between the man-made laws of the city, and the unwritten, permanent laws of the the gods. It is to these unwritten laws that she appeals in justifying her actions against Creon's proclamations. The Greek word for 'laws', nomoi, has a broader scope than the English term conveys - it can be translated as 'conventions' or 'customs' and can cover the religious duties such as burial of the dead. There is nothing metaphorical about such 'unwritten' nomoi: Aristotle even quotes Antigone in recommending lawyers to appeal to unwritten laws when the written laws are against them. For Antigone, there is a conflict between these unwritten laws, and those pronounced by Creon. Accordingly, the two characters have different conceptions of justice and the just. The Greek word for justice, dikē, and its related adjectives, occur frequently throughout the play. Both Creon and his opponents, Antigone and Haimon, appeal to dikē to support their decisions. Creon seems to identify justice with the will of the ruling party, whilst for Antigone and Haimon, it is a super-human concept that is independent of the arbitrary decisions of any mortal ruler. This dispute reflects contemporary debates surrounding the nature of justice: Plato, writing in the first half of the fourth century BC, depicts the fifth-century thinker Socrates as arguing that justice is natural and objective, against opponents who argue that justice is simply the will of the more powerful. In Sophocles' play, there is little doubt that Creon's conception of justice is proven inadequate. That the downfall of his family and his personal suffering come as a direct result of his actions is assumed by all remaining characters at the end of the play. His folly reveals a central predicament in Sophoclean drama and in Greek theology: there is a divine, cosmic system of justice, but it is one that is usually impossible for mortals to understand until it is too late. The motif of 'learning too late' is commonplace in Greek tragedy, and Creon conforms to this literary convention, as the chorus' statements at the end of the play make clear. Only a select few mortals - notably the blind prophet Teiresias - can have a privileged, albeit still limited, understanding of this system before the catastrophes unfold. 'Justice', or rather dikē, in this sense of 'divine order' was taken by some early Greek philosophers as a governing principle, not only of ethical behaviour, but also of the rules of physics. Anaximander (early 6th century BC) saw the universe as composed fundamentally from opposite qualities - such as the hot and the cold, the dry and the wet - that give each other 'justice and reparation' for injustices committed, as a result of which some balance is maintained in the universe. Similarly, Heraclitus (late 6th century BC) saw 'justice' as keeping the Sun within its established limits. Viewed in this context, we can see Creon's actions as violations of this cosmic order: the deceased Polyneices ought to be buried, but Creon prevents that from happening; conversely, he orders Antigone to be entombed whilst still alive. After his punishment, he himself becomes, in the words of the messenger, a 'living corpse'. The balance is thus settled for Creon's blurring of the distinction between the living and the dead by refusing Polyneices' burial. This enactment of cosmic 'justice' might be taken to support the notion that Creon and Antigone embody contrary principles. Yet their actions can also be explained by recognisably human motivations: Antigone no longer fears death, and even expresses suicidal thoughts, because of the immense suffering that she has experienced in the form of her family's tribulations; Creon is a new ruler who is paranoid that his rule is not accepted - he refuses to back down as he fears it will undermine his authority. The characters appeal to general principles, which place their specific conflict in a wider cosmic context - it is perhaps this feature which has aroused such philosophical interest in the play - but they are not reducible to those principles alone. Creon is a flawed and inconsistent ruler, and Antigone's ultimately self-destructive act is detrimental to her household, for it prevents her from continuing the family line. The play thus presents conflicts of principle and of character, but offers no easy resolutions: Antigone's desire for Polyneices' burial may be vindicated by the course of the narrative, but the gods still allow her to perish. In developing the imagined consequences of these conflicts of both character and principle, Sophocles unsettlingly exemplifies one of the virtues that Aristotle identified in the plots of great tragedies: that the course of events seems inevitable, but only in retrospect. Questions and activities: 1. Should you be more loyal towards your family or towards your country? Come up with reasons in support of both sides of the argument - how do your reasons compare with what is said by Antigone and Creon? 2. If we do not agree with traditional Greek beliefs about the the gods and justice, how does that affect our appreciation of the play? 3. Given that she knows that this action will lead to her death, is Antigone right to bury Polyneices? Explain your answer with reference to the text. 4. I've learned through my pain (Creon): What exactly has Creon learned? Does the play make this clear and does it matter? Suggested Reading and Further ResourcesAn enormous amount has been written on Greek tragedy in general, and on Sophocles' Antigone in particular. The following may be recommended as accessible introductions to the play and the genre: - Brown, A., Sophocles' Antigone (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1987) - an edition of the Greek text with translation and commentary.

- Cairns, D., Sophocles: Antigone (London: Bloomsbury, 2016) - a recent introduction to the play.

- Griffith, M., Sophocles: Antigone (Cambridge: CUP, 1999) - an edition and commentary of the Greek text, with an introduction that is accessible to the Greekless reader.

- Hall, E., Greek Tragedy: Suffering Under the Sun (Oxford: OUP, 2010) - a recent introduction to the genre, with specific discussion of Antigone on pp. 305-9.

- Scodel, R. An Introduction to Greek Tragedy (Cambridge: CUP, 2010) - another recent introduction to the genre, with specific discussion of Antigone on pp. 106-119.

The above works may be consulted for more advanced bibliography. - Short clips of professor Felix Budelmann (Oxford University) discussing Sophoclean drama, and Antigone in particular, are available here .

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Antigone — An Analysis of Power, Authority and Truth in Antigone, a Play by Sophocles  An Analysis of Power, Authority and Truth in Antigone, a Play by Sophocles- Categories: Antigone Sophocles Truth

About this sample  Words: 1885 | 10 min read Published: Oct 22, 2018 Words: 1885 | Pages: 4 | 10 min read  Cite this EssayTo export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: Let us write you an essay from scratch - 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help  Prof Ernest (PhD) Verified writer - Expert in: Literature Philosophy

+ 120 experts online By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email No need to pay just yet! Related Essays2 pages / 982 words 12 pages / 5520 words 3 pages / 1356 words 3 pages / 1264 words Remember! This is just a sample. You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers. 121 writers online  Still can’t find what you need?Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled Throughout the play Antigone by Sophocles, the character of King Creon issues a decree that becomes a central point of conflict. This decree states that Polyneices, the brother of Antigone, is not to be given a proper burial, [...] Antigone, the protagonist of Sophocles' eponymous tragedy, is a character who has fascinated audiences and scholars for centuries. Her actions, driven by a potent mix of familial loyalty, religious duty, and moral conviction, [...] From ancient Greek literature, the concept of the tragic hero has emerged as a captivating and enduring archetype. Sophocles, one of the renowned playwrights of this era, masterfully crafted the character of Antigone, a young [...] In Sophocles' tragedy "Antigone," the theme of loyalty is deeply woven into the fabric of the narrative, driving the actions and decisions of the characters. The titular character, Antigone, finds herself at the crossroads of [...] Sophocles's Theban plays tell the story of families afflicted by generations of personal tragedy. Unlike epics such as the Iliad, whose portrayals of whole-scale war, death, and destruction convey a sense of near-apocalyptic [...] The word “feminism” was first officially coined by French socialist Charles Fourier to be used to describe equal rights and social standing for women in the 1890’s. Throughout time, the meaning has changed, but the underlying [...] Related TopicsBy clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails. Where do you want us to send this sample? By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy. Be careful. This essay is not unique This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before Download this Sample Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper. Please check your inbox. We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together! Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy . - Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

– An Open Forum for Classics Sophocles’ Antigone and the Sources of Human EthicsDavid Konstan It is in the nature of tragedy to pose questions concerning human behavior and the means of responding to ethical dilemmas. It does so by exhibiting conflicts between individuals, which bear not only on private interests but also include a public dimension, the norms and laws of citizens in their social and political context. Nowhere is this more the case than in Sophocles’ Antigone (442/1 BC), which explicitly stages the collision between different ways of understanding justice and law. [1] This paper is an abbreviated version of a talk entitled “Antígona y las fuentes de la ética humana” which was delivered on 22 April 2011 in a Coloquio de Bachillerato at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, on the topic of “Reflexiones sobre la condición humana desde la tragedia griega”. I thank Nazyheli Aguirre for the invitation to present that paper and for her kind permission to publish an English version. Luis Gil, a philologist of the first order, who published a book on censorship in the Classical world during the epoch of Franco in Spain, explains in the preface to his translation of the play: Since Hegel, who interpreted [ Antigone ] as a conflict between two equally valid spheres of right – that of the state and that of the family – to our day, the opinions of critics have been divided between two antithetical positions, as usually happens when it is a matter of commenting on works of genius which offer abundant food not only for the inquisitiveness of philologists but also for analytical and philosophical speculation. [2] Luis Gil (trans.), Sófocles Antígona (Guadarrama, Madrid, 1969). On the one hand, Gil observes, “the basis of the conflict in the Antigone couldn’t be simpler: a girl dies because she has disobeyed an edict of the established power which comes up against ethico-religious imperatives of a higher order… Viewed in this schematic way…, Antigone for her part is wholly in the right, and Creon wrong.” Indeed, it is difficult not to sympathize with the poor heroine, who dies for her love of her brother, for her loyalty to her family, and above all for her respect for divine law, which take priority over those of human beings and their governments.  Nevertheless, the question is not so simple. If anyone at all can appeal to eternal laws, as she or he happens to understand them, what happens to civic discipline, order, and social justice? Is Antigone really right when she insists upon burying, within the borders of Thebes, an enemy of the state who is, to be sure, her brother but who organized an attack against his own city in order to recover the throne? As Gil writes, “at the very highpoint of dictatorships, greater attention was paid, for the first time, to the figure of Creon, whose arguments acquired greater relevance in those troubled times.” So too another great philologist, Antonio Tovar, who during the Spanish Civil War (1936–9) took the side of the Francoists and taught for many years in the University of Salamanca, saw in Creon the “representative of a rational kind of politics, which was doomed inevitably to collide with the traditional and irrational factors represented by Antigone.” [3] “Antígona y el tirano o la inteligencia en la política,” Escorial 10 (1943) 37–56. Tovar had produced an edition of the play with notes the previous year. It is true, in fact, that Creon has a greater role in the drama, and it would have been the protagonist – that is, the main actor – who played his part in Athens, whereas Antigone exits the stage well before the end. It is Creon, not Antigone, who is the central character in the play: the tragedy is his, his is the defeat, as was argued, among others, by Francisco Rodríguez Adrados: “It is the king at the height of his power who is humiliated over the course of the play.” [4] “ Religión y política en la Antígona ,” Revista de la Universidad de Madrid 13 (1964) 493–523, at 517.  Now, as Luis Gil argues, “Creon’s guilt, which is implied in the words of the Coryphaeus when he suggests that the burial of Polynices is a divine act, becomes ever clearer in his successive conversations with Antigone, Haemon, and Tiresias, up to the point that he himself, if not persuaded of his errors, is at least anxious about the scope of his decree and decides to revoke it at once.” In respect to the play itself, then, I think it is clear that Gil is entirely right. And yet, when he says, “it is Antigone who combines, for good or for ill, all the characteristics of the heroic protagonists of Sophoclean tragedy,” it seems to me that Creon does so just as much. Gil himself offers a different interpretation of Sophocles’ purpose in creating a character as radical as Antigone. He writes: Sophocles had wished to present to his fellow citizens a new model of civic heroism, as opposed to the heroic ideal; a heroism that surpassed the individualistic heroism of epic heroes, transforming their sense of personal honor into an elevated concept of duty. Perhaps so. And yet, Antigone gives reason and justifications for her behavior, and regarded from a philosophical point of view, we are obliged to evaluate her arguments and place them in the context of Greek thought of the period concerning the concepts of right and the foundation of the laws. So let us take a closer look at the text where Antigone clarifies her position. Creon : And yet you dared to break those very laws? Antigone : Yes. Zeus did not announce those laws to me And Justice living with the gods below sent no such laws for men. I did not think anything which you proclaimed strong enough to let a mortal override the gods and their unwritten and unchanging laws. They’re not just for today or yesterday, but exist forever, and no one knows where they first appeared. So I did not mean to let a fear of any human will lead to my punishment among the gods. I know all too well I’m going to die— how could I not?—it makes no difference what you decree. And if I have to die before my time, well, I count that a gain. When someone has to live the way I do, surrounded by so many evil things, how can she fail to find a benefit in death? And so for me meeting this fate won’t bring any pain. But if I’d allowed my own mother’s dead son to just lie there, an unburied corpse, then I’d feel distress. What’s going on here does not hurt me at all. If you think what I’m doing now is stupid, perhaps I’m being charged with foolishness by someone who’s a fool. (449–71; trans. Ian Johnston) [5] The Greek text, along with a different English translation, can be explored here .  What value would this recourse to laws that are unwritten and yet eternal have had in the eyes of contemporary Athenians? There is a less widely known text, composed by Xenophon, in which a discussion between Socrates and the sophist Hippias raises precisely this issue. It is found in the fourth book of his Memorabilia or Reminiscences of Socrates . When Hippias asks Socrates for his definition of justice, or more precisely of “the just” (τὸ δίκαιον, to dikaion ), he replies that his behavior over the course of his entire life testifies to his beliefs: “To abstain from what is unjust is just” ( Mem . 4.4.11, trans. Marchant). Socrates then asks: “Does the expression ‘laws of a state’ convey a meaning to you?” Hippias replies: “Covenants made by the citizens whereby they have enacted what ought to be done and what ought to be avoided.” The dialogue continues: Socrates: “Then would not that citizen who acts in accordance with these act lawfully, and he who transgresses them act unlawfully?” Hippias: “Yes, certainly.” Socrates: “And would not he who obeys them do what is just, and he who disobeys them do what is unjust?” Hippias: “Certainly.” Socrates: “Then would not he who does what is just be just, and he who does what is unjust be unjust?” Hippias: “Of course.” Socrates: “Consequently he who acts lawfully is just, and he who acts unlawfully is unjust.” ( Mem . 4.4.13) [6] The Greek text, along with a different English translation, is available here . Hippias then offers an objection to Socrates’ claim: “‘Laws,’ said Hippias, ‘can hardly be thought of much account, Socrates, or observance of them, seeing that the very men who have passed them often reject and amend them.’” Socrates replies: “Yes, and after going to war, cities often make peace again.” Hippias agrees, and Socrates resumes: “Then is there any difference, do you think, between belittling those who obey the laws on the ground that the laws may be annulled, and blaming those who behave well in wars on the ground that peace may be made?” ( Mem . 4.4.14). Socrates says much more about the advantages that derive from an absolute respect for the laws, and he concludes: “So, Hippias, I declare lawful and just to be the same thing” ( Mem . 4.4.18). Antigone, have you been listening?  Now, how shall we interpret the fact that Socrates himself boasts that he did not obey the leaders of the state, and this on more than one occasion? In fact, just before citing Socrates’ view with respect to obedience to the laws, Xenophon remarks: And when the Thirty [tyrants] laid a command on him that was illegal, he refused to obey. Thus he disregarded their repeated injunction not to talk with young men; and when they commanded him and certain other citizens to arrest a man on a capital charge, he alone refused, because the command laid on him was illegal. ( Mem . 4.4.3) But how, then, may one distinguish between the laws, strictly speaking, and illegal orders? Let us return, then, to the passage that we have been examining. Immediately after the words that I quoted a moment ago, where Socrates says, “I declare lawful and just to be the same thing,” and without any transition, Socrates asks: “Do you know what is meant by ‘unwritten laws,’ Hippias?” And Hippias replies: “Yes, those that are uniformly observed in every country,” that is, universal laws, which do not change from one place to another or from one society to another. Socrates continues: “Could you say that men made them?” Hippias: “Nay, how could that be, seeing that they cannot all meet together and do not speak the same language?” Socrates: “Then by whom have these laws been made, do you suppose?” Hippias: “I think that the gods made these laws for men. For among all men the first law is to fear the gods.” Socrates: “Is not the duty of honoring parents another universal law?” Hippias: “Yes, that is another.” Socrates: “And that parents shall not have sexual intercourse with their children nor children with their parents?” This last question arouses a doubt in Hippias’ mind, and he replies: “No, I don’t think that is a law of God.” “Why so?” “Because I notice that some transgress it” ( Mem . 4.4.19-20). Before indicating how Socrates responds to this challenge, we may observe that two of the laws that touch on human relations – the obligations to honor one’s parents and not to commit incest – have a particular relevance to the situation of Antigone and her family. For she manifests a reverence for her elder brother, who is practically like a father, and she is the product of an incestuous act, the sexual union between a son and a mother. Socrates, however, has a ready answer: “Yes, and they do many other things contrary to the laws. But surely the transgressors of the laws ordained by the gods pay a penalty that a man can in no way escape, as some, when they transgress the laws ordained by man, escape punishment, either by concealment or by violence” ( Mem . 4.4.21). Might Socrates be thinking here of tragedy, and more specifically of Sophocles’ Antigone ?  Aristotle makes the connection with tragedy explicitly in the first book of his Rhetoric : It will now be well to make a complete classification of just and unjust actions. We may begin by observing that they have been defined relatively to two kinds of law, and also relatively to two classes of persons. By the two kinds of law I mean particular law and universal law. Particular law is that which each community lays down and applies to its own members: this is partly written and partly unwritten. Universal law is the law of Nature. For there really is, as every one to some extent divines, a natural justice and injustice that is binding on all men, even on those who have no association or covenant with each other. It is this that Sophocles’ Antigone clearly means when she says (456–7) that the burial of Polynices was a just act in spite of the prohibition: she means that it was just by nature. Not of to-day or yesterday it is, But lives eternal: none can date its birth. ( Rhetoric 1.13, trans. W. Rhys Roberts) [7] The Greek text, with English translation, can be read here . Aristotle cites as well Empedocles’ injunction not to kill any living thing, since this is not just for some and for others unjust, Nay, but, an all-embracing law, through the realms of the sky Unbroken it stretcheth, and over the earth’s immensity. (B135) Plato too refers to unwritten laws in his last dialogue, The Laws , where the Athenian proclaims: all the regulations which we are now expounding are what are commonly termed ‘unwritten laws’. And these as a whole are just the same as what men call ‘ancestral customs’… For it is these that act as bonds in every constitution, forming a link between all its laws…, exactly like ancestral customs of great antiquity, which, if well established and practised, serve to wrap up securely the laws already written, whereas if they perversely go aside from the right way. (Book 7, 793a-b, trans. R.G. Bury) [8] The Greek text can be studied here .  Now, in the Classical world there was no concept of human or natural rights, or of human dignity as such. It is in part for this reason, perhaps, that the people appealed to divine or universal laws. But did the Greeks count, among the unwritten laws, the right, or rather the obligation, to bury one’s relatives, irrespective of their deeds, including that of having recruited an army, with troops from hostile cities, in order to conquer one’s own fatherland? In any case, in Athens at the time of Sophocles it seems it was not absolutely prohibited to leave the corpse of an enemy exposed. Vincent Rosivach summarizes the attitude of the Greeks in the fifth century BC: • From at least the fifth century onward the Athenians were prepared to refuse burial at least in Attic soil to traitors and to temple robbers. • For the Greeks in general in the fifth century and later victors in combat were still under no obligation to bury the enemy dead themselves but Panhellenic custom now required them to allow the defeated side to recover their dead for burial. [9] Vincent Rosivach, “ On Creon, Antigone and Not Burying the Dead ,” Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 126 (1983) 193–211, quotation from p. 206, points 1 and 3 (of 5). In connection with the Antigone , Rosivach concludes that Creon, as king of Thebes, was under no obligation to bury Polynices, since he had died in battle as a foreign invader. Furthermore, Creon was acting in the name of the state, not out of personal enmity. Nevertheless, his act would not have been wholly acceptable in the fifth century, and other characters in tragedy who forbid burial are all portrayed negatively.  Sophocles’ Antigone is not a political or philosophical treatise but a theatrical work, and there is no necessity to justify the action of its heroine logically or by way of syllogistic arguments. The prophet Tiresias reports to Creon the alarming omens that have resulted from his decree. Creon, for his part, does not wish to recognize the significance of these events, and accuses the seer of greed: “The tribes of prophets – all of them – are fond of money” (1055). In the end, however, Creon, by now terrified, yields to the judgment of Tiresias. Sophocles is affirming a religious thesis, not a political one: that the family, in the end, counts for more than the decrees of rulers. Jordi Balló and Xavier Pérez, in their essay, “La desobediencia civil” (“Civil Disobedience”), appended to the translation by Luis Gil, describe Antigone in exalted language: A devoted fighter, but also a pious woman, Antigone is never moved by hatred but by love… She has been regarded as an antecedent of messianic figures of the stature of Christ himself, figures invariably graced with the qualities of Antigone… What Antigone cannot tolerate about Creon is that he abrogates, by means of his decree, the value of religious beliefs that endow life with a higher meaning, beliefs that ultimately restrict the power of the State. We ought to appreciate, nevertheless, that Antigone does not sacrifice herself for strictly religious reasons nor for humanity in general, but for a beloved brother, a limited act that is not separable from the family context. It is family on which Antigone insists, and which forms the core of the drama.  Bonnie Honig, a specialist in political science, has dedicated a book to Antigone, under the title Antigone, Interrupted (CUP, 2013), in which she defends the hypothesis that Ismene plays a much more active role in the drama than that supposed by the great majority of scholars, who have regarded her as an example of passivity and servility, at the opposite extreme from her sister. We know that Creon’s rage is triggered by the fact that someone has covered the body of Polynices with dust. But who was it? It is commonly assumed that it was Antigone, who certainly returned to cover it after the guards brushed away the dust and left the body exposed once more to the air. In reality, according to Honig, it was Ismene who dared to bury the body of her brother that first time, and she represents the value of conspiracy and secrecy in opposing a tyranny. Others, however, have argued that, on the contrary, the merit of Ismene resides precisely in her recognition of the respect owed to the laws and to the decrees of the king. Bonnie Honig, again, in an article published in 2011, writes: In a recent paper…, philosopher Mary Rawlinson focuses on Ismene as a better model for feminist politics than her more renowned sister. Ismene privileges the world of living, Rawlinson argues, and she looks toward the future. “Why should feminists valorize Antigone’s embrace of the dead brother over the sister?” she asks. [10] Bonnie Honig, “Ismene’s forced choice: sacrifice and sorority in Sophocles’ Antigone ,” Arethusa 44 (2011) 29–68, citing Mary Rawlinson, “Antigone, agent of fraternity: how feminism misreads Hegel’s misreading of Antigone , or Let the other speak” (unpublished); quotation on p. 42. Radical courage, the idea that the model for women must be that of the militant hero, like an Ajax or Achilles, is not necessarily the best of traits, whether for women or for men, however “macho” they may be. Why suppose that valor in a woman, or in anyone, must possess the traits of a warrior instead of a spirit of reconciliation, and of tenderness? We may grant that, within the context of the play Antigone , there can be no doubt that she is right, and that Creon is not. But the relationship between the drama and philosophy is not exhausted by this recognition. We have not only the right but also the obligation to interrogate the tragedy and draw from it all the wisdom that lurks implicitly within it. In other words, the conversation does not stop at this point – rather, it is where it begins.  David Konstan is Professor of Classics at New York University. He has published books on ancient ideas of friendship, the emotions, forgiveness, beauty, love, and, most recently, on sin, as well as studies of Classical comedy, the novel, and philosophy. He is a past president of the American Philological Association (now the Society for Classical Studies). Further Reading Antigone has attracted the attention of a great many scholars as well as critics at large. Here is a sample of recent studies that place the tragedy in the context of modern legal, psychological, and political theory: Judith Butler, Antigone’s Claim: Kinship Between Life & Death (Columbia UP, New York, 2000), finds in the Antigone a different model for the elementary structure of the family. The two following essays explore the ethical complexities of the tragedy: Lukas van den Berge, “Sophocles’ Antigone and the Promise of Ethical Life: Tragic Ambiguity and the Pathologies of Reason,” Law and Humanities 11 (2017) 205–27; and Theodore Koulouris, “Neither Sensible, Nor Moderate: Revisiting the Antigone ,” Humanities 7.60 (2018); doi: 10.3390/h7020060 . All are conscious of the importance of feminist readings of the play. Share this article via:Notes [ + ] Notes | 1 | This paper is an abbreviated version of a talk entitled “Antígona y las fuentes de la ética humana” which was delivered on 22 April 2011 in a Coloquio de Bachillerato at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, on the topic of “Reflexiones sobre la condición humana desde la tragedia griega”. I thank Nazyheli Aguirre for the invitation to present that paper and for her kind permission to publish an English version. | | 2 | Luis Gil (trans.), (Guadarrama, Madrid, 1969). | | 3 | “Antígona y el tirano o la inteligencia en la política,” 10 (1943) 37–56. Tovar had produced an edition of the play with notes the previous year. | | 4 | “ ,” 13 (1964) 493–523, at 517. | | 5 | The Greek text, along with a different English translation, can be explored . | | 6 | The Greek text, along with a different English translation, is available . | | 7 | The Greek text, with English translation, can be read . | | 8 | The Greek text can be studied . | | 9 | Vincent Rosivach, “ and Not Burying the Dead,” 126 (1983) 193–211, quotation from p. 206, points 1 and 3 (of 5). | | 10 | Bonnie Honig, “Ismene’s forced choice: sacrifice and sorority in Sophocles’ ,” 44 (2011) 29–68, citing Mary Rawlinson, “Antigone, agent of fraternity: how feminism misreads Hegel’s misreading of , or Let the other speak” (unpublished); quotation on p. 42. | - Ancient Religion

- Competitions

- Greek Language

- Greek Literature

- Latin Language

- Latin Literature

- Material Culture

- The Classical Tradition

- The Future of Classics

- The New Naso

- Uncategorized

Sir Richard C. Jebb, Commentary on Sophocles: Antigone("Agamemnon", "Hom. Od. 9.1", "denarius") All Search Options [ view abbreviations ] Hide browse bar Your current position in the text is marked in blue. Click anywhere in the line to jump to another position: This text is part of:- Greek and Roman Materials