Creating Your Assignment Sheets

Main navigation.

In order to help our students best engage with the writing tasks we assign them, we need as a program to scaffold the assignments with not only effectively designed activities, but equally effectively designed assignment sheets that clearly explain the learning objectives, purpose, and logistics for the assignment.

Checklist for Assignment Sheet Design

As a program, instructors should compose assignment sheets that contain the following elements.

A clear description of the assignment and its purpose . How does this assignment contribute to their development as writers in this class, and perhaps beyond? What is the genre of the assignment? (e.g., some students will be familiar with rhetorical analysis, some will not).

Learning objectives for the assignment . The learning objectives for each assignment are available on the TeachingWriting website. While you might include others objectives, or tweak the language of these a bit to fit with how you teach rhetoric, these objectives should appear in some form on the assignment sheet and should be echoed in your rubric.

Due dates or timeline, including dates for drafts . This should include specific times and procedures for turning in drafts. You should also indicate dates for process assignments and peer review if they are different from the main assignment due dates.

Details about format (including word count, documentation form) . This might also be a good place to remind them of any technical specifications (even if you noted them on the syllabus).

Discussion of steps of the process. These might be “suggested” to avoid the implication that there is one best way to achieve a rhetorical analysis.

Evaluation criteria / grading rubric that is in alignment with learning objectives . While the general PWR evaluation criteria is a good starting place, it is best to customize your rubric to the specific purposes of your assignment, ideally incorporating some of the language from the learning goals. In keeping with PWR’s elevation of rhetoric over rules, it’s generally best to avoid rubrics that assign specific numbers of points to specific features of the text since that suggests a fairly narrow range of good choices for students’ rhetorical goals. (This is not to say that points shouldn’t be used: it’s just more in the spirit of PWR’s rhetorical commitments to use them holistically.)

Canvas Versions of Assignment Sheets

Canvas offers an "assignment" function you can use to share assignment sheet information with students. It provides you with the opportunity to upload a rubric in conjunction with assignment details; to create an upload space for student work (so they can upload assignments directly to Canvas); to link the assignment submissions to Speedgrader, Canvas's internal grading platform; and to sync your assigned grades with the gradebook. While these are very helpful features, don't hesitate to reach out to the Canvas Help team or our ATS for support when you set them up for the first time. In addition, you should always provide students with access to a separate PDF assignment sheet. Don't just embed the information in the Canvas assignment field; if students have trouble accessing Canvas for any reason (Canvas outage; tech issues), they won't be able to access that information.

In addition, you might creating video mini-overviews or "talk-throughs" of your assignments. These should serve as supplements to the assignment sheets, not as a replacement for them.

Sample Assignment Sheets

Check out some examples of Stanford instructors' assignment sheets via the links below. Note that these links will route you to our Canvas PWR Program Materials site, so you must have access to the Canvas page in order to view these files:

See examples of rhetorical analysis assignment sheets

See examples of texts in conversation assignment sheets

See examples of research-based argument assignment sheets

Further reading on assignment sheets

- Writing Center

Designing Assignment Sheets and Grading Rubrics

Designing course documents.

The assignment sheet and grading rubric are two important documents that make assignment requirements and assessment criteria transparent to students. These documents are closely related but communicate slightly different things.

This resource offers some ideas on what to consider when designing these important course documents.

Assignment Sheets

An assignment sheet, or prompt, should clearly communicate to students what the assignment’s expectations are. They should also be an example of what the instructor considers “good writing.” For example, if students are expected to write something concise, complete, and with an awareness of audience, the assignments sheet should do that, too. Show students the kind of writing that is expected of them!

An assignment sheet communicates what the instructor (or the discipline) values in writing. Framing it in that way can help students aim not just for a grade, but for growth as a writer in the field.

The following guiding questions can help instructors clarify what they want from students, which will help as they write the assignment sheet and can also inform the rubric’s design:

1. What should students learn from doing this assignment?

a. These should relate directly to the course objectives and outcomes.

2. What knowledge or skills should students demonstrate?

a. These should be things that have been introduced, practiced, and reviewed in class.

3. What characteristics of the final product will demonstrate that students have learned the desired outcomes?

a. It’s likely that one assignment cannot address all desired outcomes. Prioritize the most important ones.

b. These criteria can then be used to define rubric categories. E.g. a clear thesis statement, precise and concise technical writing, strong organization, etc.

Finally, make sure the assignment sheet or prompt answers all the following questions:

1. Who (Audience and writer):

a. Who is the audience?

b. What is the writer’s role? I.e. Is there collaboration involved? Are there check-ins with the instructor? Is AI allowed?

2. What (Genre):

a. What is being written, and what is necessary for this type of writing?

b. What citation format should be used?

3. When and Where (Policies):

a. When and where do students submit things?

4. Why (Purpose):

a. Why are students doing this assignment, and why now?

Assignment sheets give students the instructor’s expectations, and rubrics communicate how well they have met those expectations. While it may seem that the rubric re-states many of the criteria in the assignment sheet, it should be written with the goal of communicating information back to the students about their writing.

The process of designing a rubric can be a helpful way for instructors to think through how the assignment meets course goals, which will make it easier to communicate those criteria to students both in class and via the assignment sheet. Some instructors feel that grading with rubrics is more consistent and efficient.

There is enormous variability in rubrics and creating one that works for the graders, captures the goals of the assignment, and is meaningful for students is part of an iterative process of design.

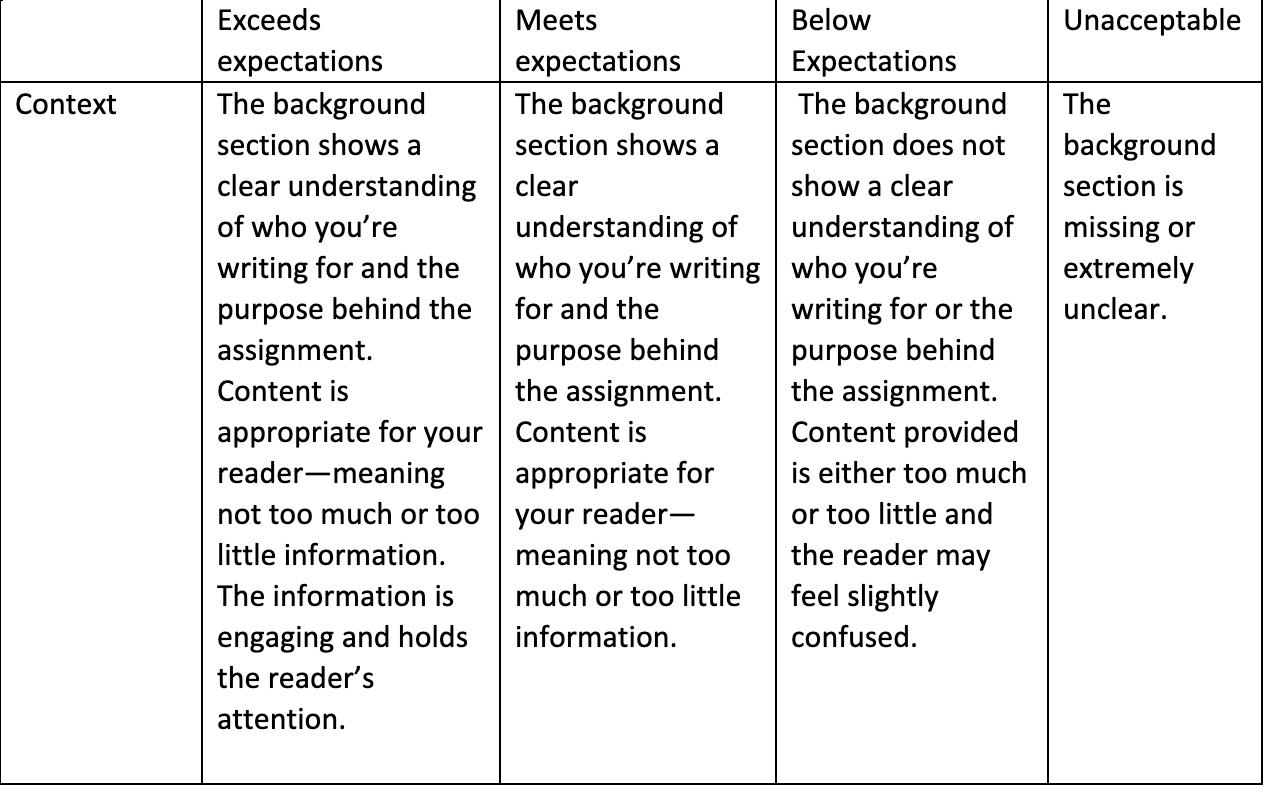

Creating a Rubric

Determine a rating scale for each assignment criterion that was prioritized earlier. The most basic rubrics define what adequate and inadequate performance looks like for each category, but more descriptors can be helpful. For example, defining “outstanding” performance gives students a sense of how to go above and beyond. More descriptors at intermediate levels give students feedback on their work beyond “adequate.”

Examples of rating scales:

· Exceeds standards, meets standards, approaching standards, below standards

· Represents strong work, accomplishes the task, needs improvement

· Well done, satisfactory, needs improvement, incomplete

Next, for each category of the rating scale, describe the specific criteria. For example, if one of the assessment markers is: “The paper makes a strong argument,” define what a well-crafted argument is, then define a satisfactory one, an incomplete one, etc.

Choosing rubric types:

A holistic rubric provides a broad general description of the requirements for each level of performance. Multiple criteria are articulated for each proficiency level, so the student’s work will necessarily into a fairly broad category, maybe A, B, C, or D.

For example: “An A paper clearly defines the main points which are in turn well supported with evidence and references. The technical content is correct. The format is organized so that the reader can easily navigate the document. The figures/tables are presented clearly. The vocabulary use is appropriate for the reader and the document is professional in appearance and style.”

An analytic rubric has performance descriptors for each assignment criteria, which allows for more specific feedback for each area. This type of rubric may list criteria such as organization, clarity, grammar, etc. with a description of multiple levels of proficiency for each.

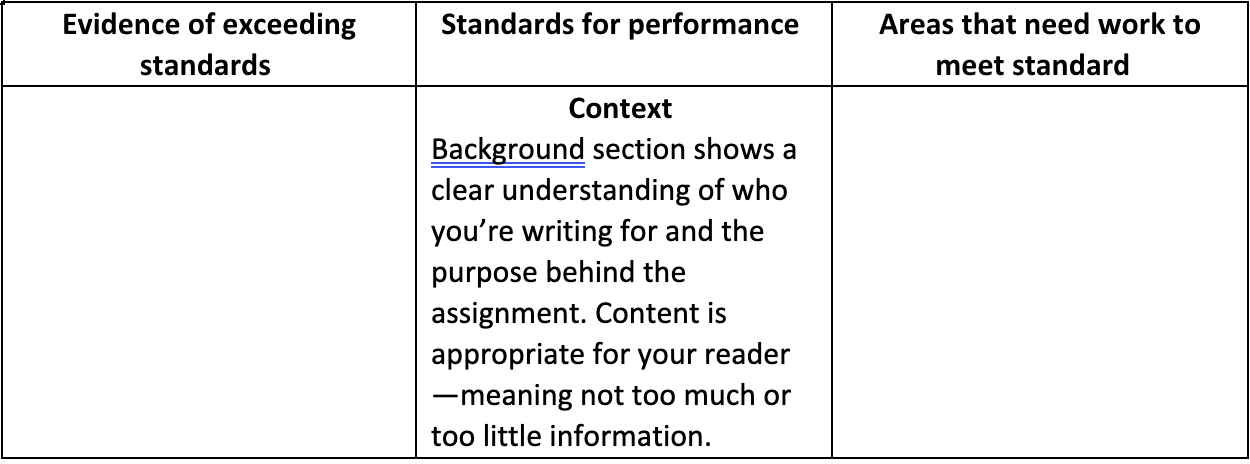

A single-point rubric is a rubric that is divided into three-columns. The middle column defines the proficiency standard for each criterion being assessed while leaving empty columns on either side of this description for the instructor to write comments on the ways in which the standards were exceeded or not met. A single point rubric allows the instructor to define the expected outcome for the assignment while tailoring feedback for each assessment category.

Revising and norming rubrics:

No rubric will work perfectly the first time. Be open to adjusting the rubric as you use it and as you get feedback from students and other graders. Over time it will become more refined.

If there are multiple graders using the same rubric (TAs, for example) take time to norm before grading the first assignment. Norming means having multiple instructors grade the same student paper with the same rubric and then talking through why each grader chose to give it the score they did. Doing this with a few student papers will help graders be more consistent in interpreting the scale and criteria.

Finally, it’s important to acknowledge that grading writing, even with a rubric, is inherently subjective. Be clear about that with students and discuss how the rubric is an attempt to make that subjectivity as transparent as possible.

Consistency and Equity in Grading: The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning at Harvard University

Active and Alternative Assessments: Missouri Online

How to Use Rubrics: MIT Teaching + Learning Lab

Know Your Terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics: Cult of Pedagogy

Types of Rubrics: Center for Teaching and Learning: DePaul University

The Writing Center

Montana State University P.O. Box 172310 Bozeman, MT 59717-2310

Wilson Hall 1-114, (406) 994-5315 Romney Hall 207, (406) 994-5320 MSU Library 152

[email protected]

Facebook Twitter Instagram

Job Opportunities FAQ & How To

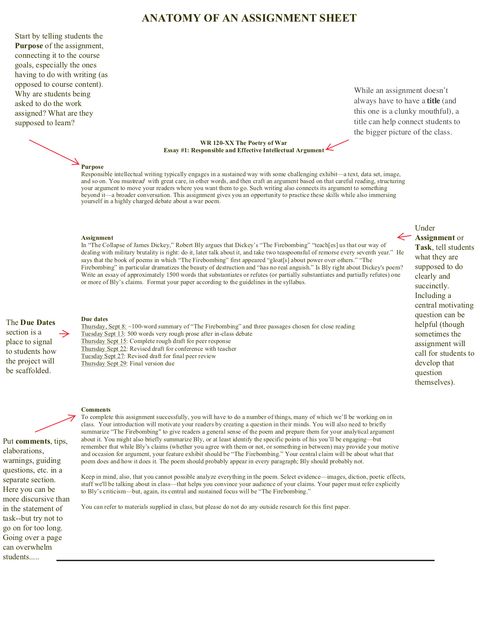

Anatomy of an Assignment Sheet

Guides & tips.

In this guide, we invite instructors to think through the different sections of an assignment sheet and perhaps take a fresh look at their own assignment sheets. At the bottom of the page, you’ll find some insights into more effective assignment sheets from Writing Consultants working in the CAS Writing Center .

Key Elements

Things to Consider

- While an assignment does not necessarily have to have a title (this one’s a clunky mouthful), it can help students connect an individual assignment to the bigger context of the class.

- Start by telling students the purpose of the assignment, connecting it to the course goals, especially the ones having to do with writing as opposed to course content. Why are students being asked to do the work assigned? What are they supposed to learn?

- The due dates (or submission guidelines) section is a chance to draw students’ attention to how the assignment will be scaffolded.

- Under assignment (or task ), tell students what they are supposed to do clearly and succinctly. Including a central motivating question can be helpful, though sometimes the assignment will call for students to develop that question themselves.

- In the comments section (or additional information) you can include elaborations, warnings, guiding questions, etc. in a separate section. Here you can be more discursive than in the statement of task, but try not to go on for too long. Going over a page can overwhelm students.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about transparent assignment design and use a template for transparent assignments ( Winkelmes 2013-2016 ).

- Look at the Writing Program’s templates for major assignments in WR 120 to begin customizing your own assignment sheets.

Tips from Tutors: What Writing Consultants Say About More Effective Assignment Sheets

Keep assignment sheets short (~1 page if possible)..

- Students genuinely want to understand what’s being asked of them, but if there is too much information, they don’t always know how to prioritize what to focus on.

- Focus on specific questions you want students to answer or tasks you want them to complete. Avoid content that isn’t specifically related to the assignment itself.

- It’s generally best not to include all assignments for the semester in a single document. While it can be helpful to have one sheet or section of the syllabus with all assignments listed, it’s best to give each assignment its own document with detailed expectations.

- Students need some guidelines for assignments. Following the WP “anatomy of an assignment” guidelines (above) helps students as they move from one WR course to the next, and it also helps consultants figure out where to find key information more quickly.

Give students some choices, but be (overly) clear about your expectations.

- It’s especially challenging for WR 120 students to come up with their own “research question” and then answer it. If you’re asking them to do that, be very specific about what you want them to do and what parameters they should work within.

- Don’t give students a long list of questions to consider — or, if you do, be incredibly explicit about what questions are intended to generate ideas as opposed to what questions they actually need to answer in their paper.

- The best assignment sheets tend to be those that give students a set number of options and then ask them to pick one to answer.

Give clear (as in legible and also as in straightforward) feedback.

- Provide typed rather than handwritten comments.

- Avoid cryptic feedback like “awkward” or “?” that could be interpreted in different ways.

- If you write comments in shorthand, be sure to provide students with a key.

- Provide feedback as specific questions that students can either address themselves, or discuss with a writing consultant (or you!)

Remember WR courses are introductory courses.

- Choose course readings for written assignments that lend themselves to teaching writing as opposed to seminal texts or your personal favorites.

- Go over all readings that students are expected to write about in class and devote extra time to particularly challenging ones. If you are working on difficult topic and/or dense texts, don’t assume your students can navigate them without explicit scaffolding in class.

- Not all students have been taught how to analyze quotations and use them as evidence to support their argument, so be sure to spend time teaching these skills.

- Don’t take anything for granted. Students are coming from all kinds of educational backgrounds, and our courses meant to reinforce (but sometimes teach for the first time) skills all students will need for future college papers. You may also want to read about the “hidden curriculum” in writing classes when considering inclusivity and assumptions.

- Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

As a program, instructors should compose assignment sheets that contain the following elements. A clear description of the assignment and its purpose. How does this assignment contribute to their development as writers in this class, and perhaps beyond? What is the genre of the assignment?

An assignment sheet, or prompt, should clearly communicate to students what the assignment’s expectations are. They should also be an example of what the instructor considers “good writing.”

Under assignment (or task), tell students what they are supposed to do clearly and succinctly. Including a central motivating question can be helpful, though sometimes the assignment will call for students to develop that question themselves.

How to Design an Assignment Sheet | College Teaching TipsIf you're teaching a college course that includes paper assignments in it, here's a video where I go...

Assignment sheets should detail: the kind of writing expected. the scope of acceptable subject matter. the length requirements. formatting requirements. documentation format. the amount and type of research expected (if any) the writer’s role. deadlines for the first draft and its revision.

This guide will help you set up an APA Style student paper. The basic setup directions apply to the entire paper. Annotated diagrams illustrate how to set up the major sections of a student paper: the title page or cover page, the text, tables and figures, and the reference list.