Conservation, exposition, Restauration d’Objets d’Art

Home Issues HS Vandalism and Art The duality of Graffiti: is it va...

The duality of Graffiti: is it vandalism or art?

Introduction.

1 Graffiti is found in many societies with different cultural contexts and has become a witness and an ethnographic source of information on urban art development (Waclawek, 2011). Modes of expression are mainly related to visibility, notoriety, choice of venue, transgression, and are often a mean to react and protest while remaining anonymous, by illegally introducing messages in the public space. Contemporary graffiti is also described by its controversial issues between social, style and aesthetic forms along with vandalism aspects. Facing a worldwide plethoric production, the assumption that Graffiti is a positive urban art form raises some paradoxical questions regarding ephemerality and “visual pollution” with a growing art market demand. However, it is often seen as illicit production and vandalism asset. For instance, removing graffiti or restricting the practice of graffiti from the public space has been a controversial issue for artists and authorities. A question therefore arises: how can the aesthetic and pictorial aspects of these acts of creation be considered as acts of vandalism? ( Bengsten, 2016).

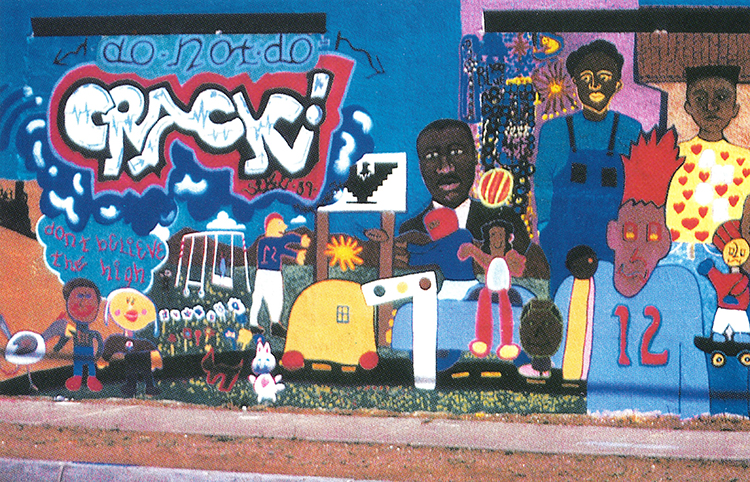

Fig. 1 Vandalism

Vandalism by Goon and Chick, 1985

© Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff

Fig. 2 Vandalism?

Keith Haring, New York, 1983

© Laura Levine/Corbis

The problem of temporality

2 Similarly, the notion of temporality, by dissociating conservation and transmission must be considered. The growing interest leads to different perceptions probably with greater attention to the act of "heritage" at the expense of the act of protest. The patrimonialization of graffiti and, to a large extent, of Street Art is an essential point, because graffiti writers or street art practitioners often see institutions as "looters" who, come to preserve cultural acts that other public institutions have condemned (Omodeo, 2016).

3 Heritage is primarily a process which, in principle, prevents any destruction or voluntary surrender of an artwork, which are a corollary of creation and its limitation of copyright in time. For most “writers”, Graffiti is not an act thought out on the basis of a future conservation. The issue is visibility and notoriety, by the number, size and/or the choice of venue. Regarding paint materials, so many spray paint brands are available to the general public in hardware stores. Graffiti writers would not necessarely comply with this rule as their preferences for brands are more related to habits, opportunities and word of mouth, along with, plastic qualities and not for resistance properties.

Alterations

4 If Graffiti question the artistic approach of the artist and the context of their creation, it also poses those of alteration mechanisms, sometimes irreversible, these colors, which are significant from the point of view of heritage conservation. This encourage today to have a different perspective than that of the material history of the work with the creative process, the components used and the effects of environment parameters and ultimately, of time (Colombini, 2017).

5 The traditional methods of conservation are questioned; which must intervene and what modifications in relation to the original one can be accepted? (Beerkens, 2005). Is it essential to invite the artist to take part in the heritage process? One must look at the field of Muralism, mainly in the USA, to find more innovative and frequent restoration procedures. Indeed, the restoration of murals, often monumental paintings, is a civic and collective act within the "neighborhood". The actors of the restoration/renovation are both volunteer civilians trained and supervised by experienced conservators, artists and more generally, of persons engaged in neighborhood committees (Shank, 2004). This is not without rewards and sometimes reveals abuses that go beyond the artistic acts.

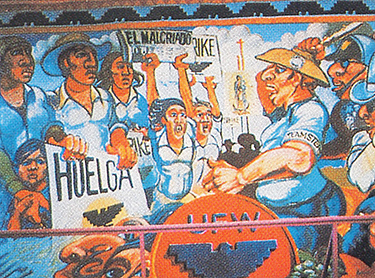

Fig. 3 Conservation

Community mural conservation

© 2014 Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles

Fig. 4 A public Art project, 1985

6 The practice of graffiti and its legislation ambiguities are at stake. Graffiti and Street Art have their own definitions and interpretations, but they have something in common with illegal acts when it comes to the artistic act carried out on surfaces without the given permission by a property owner, whether public or private. We are now witnessing a radicalization of practices both from two points of view: legality and vandalism. The character of these acts explains why some artists (not only from the graffiti scene) have seen their career highlighted with arrests, penalties and sometimes trials, while their works are copyrightable (Moyne, 2016).

7 T he question of authenticity of paint arises when, aesthetic and style expertise, may not be sufficient to ascertain whether the juridical designation of Street Art as “Art” versus graffiti as vandalism. This is even truer for legal graffiti, mainly because of the variability of quality of the known and the good quality of spray paints, supposedly meant to last, as opposed to, the use of cheap brands of spray paint as illegal graffiti (Marsh, 2007).

Duality of the phenomenon

8 This paper relates to the duality of the modern graffiti phenomenon, as to whether it is a vandalism act or a cultural production. It focusses on a comparison study, mainly through artist interviews, between the evolving graffiti practices in Western major cities where illegality is often reclaimed by artists, and the fast emergence of graffiti in China, where this artistic expression is not only watched through its illegal and vandalism forms, but also for its aesthetic perceptions, though practices happen in restricted areas for expressing social, anti-official and political actions (Valjakka, 2011). Graffiti are buffed, almost straight away, by city cleaners the so called “buffers”, who are in the streets to remove all sorts of inscriptions from plumbers to whatever girl ads. If they cannot scrap it out, they paint over and that is why graffiti never lasts. At the same time, the relationship with authorities has improved very much over the last few years. It is more and more common to negotiate with the police by explaining what graffiti writers are doing, colours and mode of expression for everybody, in order to, embellish the streets rather than litter or vandalize them. From a civilization where calligraphy has been the core of the artistic production, the writing on a wall has different meanings than in a Euro-American context (gangs and political + social protests). Confronting these two almost opposite approaches, it allows a better understanding of this artistic form, as to whether it is considered vandalism or art. This controversial interrogation can be illustrated by the artist Bando’s quote “Graffiti is not vandalism, but a very beautiful crime”.

List of illustrations

| Title | Fig. 1 Vandalism |

|---|---|

| Caption | Vandalism by Goon and Chick, 1985 |

| Credits | © Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff |

| File | image/jpeg, 100k |

| Title | Fig. 2 Vandalism? |

| Caption | Keith Haring, New York, 1983 |

| Credits | © Laura Levine/Corbis |

| File | image/jpeg, 68k |

| Title | Fig. 3 Conservation |

| Caption | Community mural conservation |

| Credits | © 2014 Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles |

| File | image/jpeg, 108k |

| Title | Fig. 4 A public Art project, 1985 |

| Credits | © Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff |

| File | image/jpeg, 90k |

Electronic reference

Alain Colombini , “ The duality of Graffiti: is it vandalism or art? ” , CeROArt [Online], HS | 2018, Online since 09 December 2018 , connection on 24 August 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ceroart/5745; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ceroart.5745

About the author

Alain colombini.

Contemporary art scientist. Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP), Marseille – France

By this author

- Les matériaux en polyuréthanne dans les œuvres d’art : des fortunes diverses. Cas de la sculpture « Foot Soldier » de Kenji Yanobe [Full text] Published in CeROArt , 2 | 2008

The text only may be used under licence CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 . All other elements (illustrations, imported files) are “All rights reserved”, unless otherwise stated.

The journal

- Presentation

- Information for authors

- Scientific Committee and editorial board

Full text issues

- HS | 2021 Imiter le textile en polychromie à la fin du Moyen Âge. Le brocart appliqué

- 12 | 2020 Flux 2020-2021

- 11 | 2019 Flux 2019

- HS | 2018 Four Study Days in Contemporary Conservation

- HS | 2017 Education and Research in Conservation-Restoration

- HS | Juin 2015 Tribute to Roger Marijnissen

- 10 | 2015 La restauration, carrefour d’interrelations

- HS | 2014 Teaching Conservation-Restoration

- 9 | 2014 The conservator-restorer’s knowledge and recognition

- HS | 2013 Conservation: Cultures and Connections

- HS | 2013 De l’art et de la nature

- HS | 2013 Le faux, l’authentique et le restaurateur

- 8 | 2012 Politiques de conservation-restauration

- HS | 2012 La restauration des œuvres d’art en Europe entre 1789 et 1815 : pratiques, transferts, enjeux

- 7 | 2011 Science et conscience

- 6 | 2011 Réinventer les méthodologies

- 5 | 2010 La restauration en scène et en coulisse

- 4 | 2009 Les dilemmes de la restauration

- 3 | 2009 L’erreur, la faute, le faux

- 2 | 2008 Regards contemporains sur la restauration

- 1 | 2007 Objets d’art, œuvres d’art

EGG Special Issues

- EGG 6 | 2017 First publications from young graduates in conservation

- EGG 5 | 2016 First publications from young graduates in conservation

- EGG 4 | 2014 First publications from young graduates in conservation

- EGG 3 | 2013 First publications from young graduates in conservation

- EGG 2 | 2012 First publications from young graduates in conservation

- EGG 1 | 2010 First publications from young graduates in conservation

- Call for papers

Information

- Mentions légales et Crédits

- Publishing policies

Newsletters

- OpenEdition Newsletter

In collaboration with

Electronic ISSN 1784-5092

Read detailed presentation

Site map – Syndication

Privacy Policy – About Cookies – Report a problem

OpenEdition Journals member – Published with Lodel – Administration only

You will be redirected to OpenEdition Search

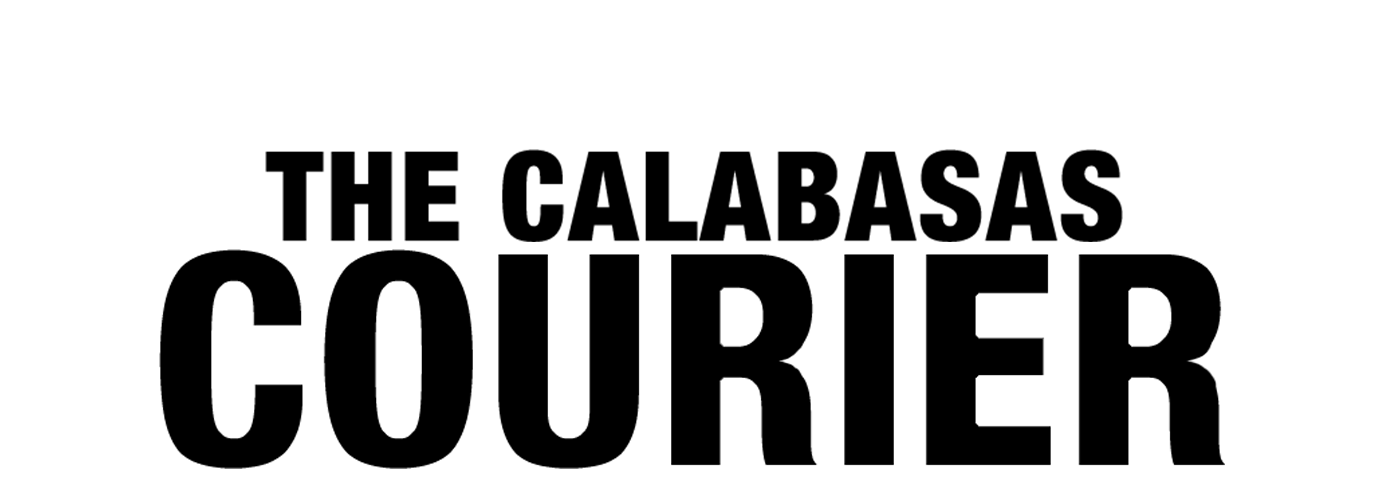

Calabasas Courier Online

Graffiti should be recognized as art, not vandalism

Graffiti covers the walls of freeways, bridges and buildings, showcasing the talent of those who create the beautiful imagery. It continues to become more widespread despite the ongoing debate of whether or not it is vandalism. This street art beautifies cities by giving them character and making them look unique and personal. As a non-violent form of expression, graffiti is a necessary outlet and should not be limited.

Buildings that are “tagged” have a more personal feel than buildings with plain white walls. Because of the appreciation for graffiti’s beauty, instead of viewing graffiti as vandalism, many realize the amount of skill necessary to create the street art and appreciate the message it delivers. Many people admire Keith Haring, a famous graffiti artist from the 80s known for his artwork around New York City. Haring’s artwork is so widely known that the city has embraced its presence around the city.

“Graffiti reflects individuals’ views on various issues and can make a dull brick wall stunningly beautiful,” said junior Megan Richardson.

Graffiti is a form of expression, and artists should be free to make their thoughts and beliefs public. Serving as a way to avoid violence, graffiti is an outlet for many to express their feelings. Making street art illegal limits the freedom of artists to create influential masterpieces. Graffiti artists create works that reflect both struggles and accomplishments and at many times display political and social messages. The paint that coats walls in communities everywhere can contain symbolism so profound that it has been compared to poetry. People around the world also know Banksy, a famous London-based graffiti artist, for his satirical street art that reflects his political views. Banksy’s work is so distinct that it has inspired Obey Propaganda, a famous clothing company. Many others are beginning to realize the influence graffiti has on the world, and famous street art will only continue to flourish.

Many believe that graffiti rebels against authority, yet the skill required to create elaborate graffiti is remarkable. The world is a canvas for graffiti artists, and they should feel free to cover it as they please.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Calabasas High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Comments (23)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Anonymous Hacker • Jun 10, 2021 at 8:49 pm

I have to write a debate for IPSHA Debating (in Australia) and this information has provided me much help. Thank you 🙂

Faye Aston • Mar 12, 2021 at 3:55 am

I’m writing a debate on this and it’s so helpful just reading ideas to write thank you so much for this website it’s helped me a lot

Chloe Wicker • Mar 5, 2021 at 8:39 am

Hello i’m in 7th Grade and I am writing an argumentative essay about Weather or not I think Graffiti should be illegal and I think it shouldn’t be this story is really helping me write my essay thanks so much for it

Jesus • Feb 5, 2021 at 8:28 am

Beautiful work

unkown • Oct 19, 2018 at 8:17 am

hmm. lameeee

carman flores • May 21, 2018 at 2:05 pm

I honestly believe that graffiti is a way for people not as wealthy as others to show that art doesnt come from intelligence but the desire to bring whats in their minds out for others t see. ~Carman Flores

Ashlynn Anthony • May 9, 2018 at 5:48 pm

I am doing an essay on this and I think all you’re comments are very helpful and the information is valid. Although I do think you should include more insite for both sides of the debate. Cheers.

nino • Mar 13, 2018 at 2:53 pm

6this article was very helpful for essay at evergreen

destiny • Jan 11, 2018 at 8:48 pm

i beleie that graffiti is art its beautiful and it allows you to pour out your feelings into a drawing

Jane • Jun 6, 2017 at 9:44 pm

I’m writing an argument to argue that graffiti is art and not vandalism and this is so helpful thankyou!

Quack • May 17, 2017 at 12:03 am

I really need some help on my debating topic

Hailey • Mar 1, 2017 at 8:13 am

Thankyou so much this helped so much with my paper i’m writing.

Brandon • Aug 18, 2016 at 1:54 pm

I am also writing an essay on this and think it is a great topic. I think all these people are really talented. Thank you for the info.

Say_savage • Feb 15, 2017 at 6:54 pm

Thanks for this I really needed this article to provide evidence that graffiti is an art thanks again

notme • Jul 1, 2016 at 1:21 pm

it is art but its better that it is illegal if it was not it wouldn’t be so prolific, so dramatic, and intensified. to get in the mind of a writer is a crazy thing but they enjoy it being illegal. if graffiti was legal it would cease to have those powerful messages they convey they say so much if a writer goes out at dead of night while no one is their. it would be like a verse with no beat if it would ever be legal…people would loose their drive for it

samantha • Jun 1, 2016 at 6:24 am

Graffiti is a beautiful non-violent to express emotion.

carly • Feb 26, 2016 at 9:31 am

I believe graffiti is art it shows emotion and skill plus an amazing talent the artists have.

Dana • Mar 22, 2016 at 11:02 am

I am writing a paper on this topic and I think this is so true

jordan • Feb 9, 2017 at 9:40 am

i am to and this is helpful for my debate

Maddie • May 14, 2018 at 4:31 am

Me to I am writting an exposition writing for it

Seth Price • Mar 26, 2017 at 9:39 pm

im doing a debate on this topic and I think the info is great

destiny • Jan 11, 2018 at 8:37 pm

yes i aslo agree with what you have said it also!

carman flores • May 21, 2018 at 2:02 pm

I honestly believe graffiti is a way for people who dont have any money to show that they are talented too.

The New York Times

Advertisement

The Opinion Pages

Graffiti is a public good, even as it challenges the law.

Lu Olivero is the director of Aerosol Carioca and the author of the forthcoming "Cidade Grafitada: A Journey Inside Rioʼs Graffiti Culture."

Updated July 11, 2014, 6:15 PM

Vandalism is expression and that is what makes it art. Graffiti, a vandalism sub-genre, is differentiated by its aesthetics, or its message.

However, graffiti straddles the line between pure art and pure vandalism. Though graffiti represents a challenge to the law — and sometimes serves as social commentary about the subjectivity of laws — it can simultaneously serve a public good through its nuanced social commentary and its artistry.

The arbitrary nature of how graffiti is removed or preserved highlights an interesting dissonance: the social-political oligarchy rejects the artist, and the conditions that create the art, unless the art is somehow accepted on the establishment’s terms. Enter Banksy: a British street artist, and self-described vandal, who has become a celebrated figure in the world of elite art.

Banksy’s work has unintentionally reignited the “art or vandalism” debate: though the British government has been vigilant in removing his trademark stencil art, labeling it “vandalism,” his original works and knockoffs have skyrocketed in price over the last decade. His work is often highly satirical of establishment rules and politics. Why is it that Banksy’s work is gobbled up by the same people he is critical of — yet his contemporaries are looked at as “criminals"? Why are they judged so differently?

Thirty years ago hip-hop music was labeled “noise,” and graffiti will follow the same trajectory. Perceptions about street art have already drastically changed.

For example, in Brazil, during late 1990s, it was common for graffiti artists to be harassed or shot at by the police. Today, many of the same officers support graffiti initiatives for city beautification, and as a crime deterrent. They understand that graffiti can be a career opportunity for youth in low-income neighborhoods. The growth of graffiti in Brazil, and its role in challenging the status quo, demonstrates the power of art, and its ability to create dialogue.

In the city of Rio de Janeiro, many leading street artists have put graffiti to good use for social development, founding art schools in low-income neighborhoods and partnering with the police to paint murals in run-down areas. They host large events and festivals, which bring in tourists.

It has had such an effect that this year the mayor of Rio announced the legalization of graffiti on city property that is not historical.

The truth is that despite the acceptance of graffiti, it needs the law so that it can function outside of it. This is where innovation is born, and this is what pushes the art to evolve. Had graffiti artists in Brazil painted inside the lines of the law, many internationally acclaimed artists would never have existed.

Some people may not like the message, or how it is manifested, but that doesn’t mean the message – and the medium – don’t have value.

Join Opinion on Facebook and follow updates on twitter.com/roomfordebate .

Topics: Law , art

It's Young, Cool, Creative – Let It Happen

Legal Venues Celebrate the Art Form

When does graffiti become art, it’s always vandalism.

It’s Young, Cool, Creative – Let It Happen

Value in the message and the medium, related discussions.

Recent Discussions

Not all graffiti is vandalism – let’s rethink the public space debate

Researcher in the Philosophy of Play, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Liam Miller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Earlier this month, at the opening of an exhibition dedicated to his work at Brisbane’s GOMA, David Lynch got stuck into street art, calling it “ugly, stupid, and threatening”. Apparently, shooting movies can be very difficult when the building you want to film is covered in graffiti and you don’t want it to be.

Is there a distinction between art and vandalism? This is the question that always seems to rise up when graffiti becomes a topic of conversation, as it has after Lynch’s outburst. This is, however, not just important for those of us who want to know the answers to obscure questions such as, “what is art?” It affects everyone.

Why? Because graffiti exists in our public spaces, our communities and our streets.

Let’s for a minute put aside the fact that an artist such as David Lynch, known for pushing the envelope in terms of what art is and can be, is criticising one type of art on the grounds that it is inconvenient to the kind of art that he prefers to undertake.

There is something more important to discuss here. The opinion that street art is vandalism (that is, not art) is widely held. Many people despise graffiti – but we are more than happy to line our public spaces with something much more offensive: advertising. That’s the bigger story here, the use and abuse of public space.

At heart, I think this is why people don’t like graffiti. We see it as someone trying to take control of a part of our public space. The problem is, our public spaces are being sold out from under us anyway. If we don’t collectively protect our public spaces, we will lose them.

Two types of graffiti

I would like to make a bold distinction here.

I want to draw out the difference between two kinds of graffiti: street art and vandalism.

We need something to be able to differentiate between Banksy and the kids who draw neon dicks on the back of a bus shelter. They are different, and the difference lies in their intention.

Tagging, the practice of writing your name or handle in prominent or impressive positions, is akin to a dog marking its territory; it’s a pissing contest. It is also an act of ownership. Genuine street art does not aim at ownership, but at capturing and sharing a concept. Street art adds to public discourse by putting something out into the world; it is the start of a conversation.

The ownership of a space that is ingrained in vandalism is not present in street art. In fact, street art has a way of opening up spaces as public. Street art has a way of inviting participation, something that too few public spaces are even capable of.

Marketing vandals

If vandalism is abhorrent because it attempts to own public space, then advertising is vandalism.

The billboards that line our streets, the banner ads on buses, the pop-ups on websites, the ads on our TVs and radios, buy and sell our public spaces. What longer lasting sex? A tasty beverage? To be young, beautiful, carefree, cutting edge, and happy? For only $24.95 (plus postage)!

Advertising privatises our public spaces. Ads are placed out in the public strategically. They are built to coerce, and manipulate. They affect us, whether we want them to or not. But this is not reciprocated.

We cannot in turn change or alter ads, nor can we communicate with the company who is doing the selling. If street art is the beginning of a conversation, advertising is the end. Stop talking, stop thinking – and buy these shoes!

Ads v graffiti

We are affronted by ads. They tell us we are not enough. Not good enough, not pretty enough, not wealthy enough.

At its worst, graffiti is mildly insulting and can be aesthetically immature. But at its best, it can be the opening of a communal space: a commentary, a conversation, a concept captured in an image on a wall. Genuine street art aims at this ideal.

At its best, advertising is an effective way of informing the public about products and services. At worst, advertising is a coercive, manipulative form of psychological warfare designed to trick us into buying crap we don’t need with money we don’t have.

What surprises me is that the people who find vandalism in the form of tagging and neon dicks highly offensive have no problem with the uncensored use of our public spaces for the purposes of selling stuff.

What art can do

If art is capable of anything in this world, it is cutting through the dross of everyday existence. Art holds up a mirror to the world so that we can see the absurdity of it. It shows us who we really are, both good and bad, as a community.

Street art has an amazing ability to do this because it exists in our real and everyday world, not vacuum-sealed and shuffled away in a privileged private space. Its very public nature that makes street art unique, powerful, and amazing.

If we as a community can recognise the value in street art, we can begin to address it as a legitimate expression. When we value street art as art, we can engage with it as a community and help to grow it into something beautiful.

When street art has value, our neon dicks stop being a petty and adolescent attempt at ownership, and become mere vandalism. When we value our public spaces as places where the we can share experiences, we will start to see the violence that is advertising as clearly as the dick on the back of a bus shelter.

- Advertising

- David Lynch

Head of Evidence to Action

Supply Chain - Assistant/Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Education Research Fellow

OzGrav Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

- Graffiti, its Significance and Drawbacks Words: 2003

- Street Art Graffiti as a Culture Words: 1110

- Graffiti as a Monumental Form of Art Words: 607

- Criminal Law – Is Graffiti a Crime or Not? Words: 1362

- Graffiti Evaluation and Labeling Theory Words: 557

- Graffiti: Whether It Is a Good or Bad Side of Society Words: 856

- Graffiti as a Cultural Phenomenon Words: 573

- Anthropology: Melbourne Graffiti Culture Comparing to New York Words: 2327

- Street Art, Graffiti, and Instagram Words: 608

- Art and Community Participation and Interaction Words: 1442

- The Power of Art in Society Words: 2488

- The Question of Ownership of Art Words: 1984

- What is Art? Finding a Definition Words: 1194

- Public Art and Communities’ Needs Words: 759

- The Representational Aspect of Art Words: 662

- The History and Concepts of Art Nouveau Words: 1106

- Art’ and Money Relations Words: 657

- The World of Art: Categories and Types Words: 1147

- The Role of Art in the World and Culture Words: 1472

- Arts Organizations Management Words: 2236

- Art: Dictionary, Societal, Personal Definitions Words: 1276

- Arts Education and Its Benefits in Schools Words: 729

- Cataloging Street Art: Main Features, Kinds, Shapes, and Sizes Words: 1757

- History of Ecology Topic in Art Words: 1655

- Interpreting Art: Term Definition Words: 2143

Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism?

Introduction – what is graffiti.

Graffiti is a word used to describe any writing or images that have been painted, sketched, marked, scrawled or scratched in any form on any type of property. It can be a design, figure, inscription or even a mark or word that has been written or drawn on either privately held or government owned properties. While graffiti refers to an entire scribbling or drawing, graffito describes a single scribble. Graffiti can be any form of public marking which appears as a distinguishing symbol and most of the time it comes out as a rude decoration having the form of simply written words, elaborate and complicated wall paintings or etchings on walls and rocks.

Graffiti can also be described as an unauthorized drawing or inscription on any surface situated in a public area. Apart from this graffiti also includes hideous scribbles which we often find scrawled and painted on the fences of a house, in subways, bridges, along the sides of houses and other buildings and even on trains, buses and cars. Although some look like elaborate paintings most of them are garbage which appears to have been done by small children.

Graffiti vandalism has a number of forms. The most harmful and destructive of all are the gang graffiti and tags. The former are generally used by gang members to outline their turf or threat opposite gangs. These often lead to acts of violence. Tags represent the writer’s signature and can also be complicated street art. Conventional graffiti is often hurtful and malicious and generally the act of impulsive or isolated youths. Ideological graffiti is hateful graffiti which expresses ethnic, racial or religious messages through slurs and can cause a lot of tension among the people. Sometimes the graffitists also use acid etching where they use paints mixed with acids and additional chemicals which can rankle the surface making the etchings permanent. (Wilson, 52-66)

Graffiti – Art or Vandalism

Graffiti cannot be considered as a form of art since its basic difference from art is consent or permission. Although a number of people consider graffiti to be one of the numerous art forms, most of the times graffiti is considered as unwanted and unpleasant damage to both public and government properties. In modern times almost all of the countries in the world consider the defacing of public or government owned property with any type of graffiti without taking the owner’s permission or authorization to be an act of vandalism.

Had graffiti been created without destroying someone’s belongings then even it would have appeared artistic, due to their bright use of colors, and not as an act of vandalism. Graffiti scribblers often claim that in order to improve the look of the walls and fences of one’s property they make colorful paintings on them. But this is highly questionable since they almost never take the permission of the owner of the property before making their art, turning the entire thing into vandalism. They do not have the right to destroy or change the look of one’s property without taking their permission or authority. (Smollar, 47-58)

All throughout history people have considered graffiti to be an act of vandalism since it incorporates an illegal use of public and government property. Such an act is not only mutilation of property and an ugly thing but is also very expensive to remove. Although graffiti artists use their talents to share and express their feelings, until and unless graffiti is done on an area designated for it and by somebody authorized to do so, graffiti in any form will remain to be an act of vandalism and not art.

Graffiti done without proper authority cannot be considered as art since immature vandals simply use graffiti as a means to seek infamy. Graffiti is noting more than an irresponsible and dangerous form of art promoting gang activities and truancy. Thus, we can see that there is nothing artistic about graffiti vandalism. (Austin, 450-451)

The Problem of Graffiti

The problem both the government and the people of the world face due to graffiti is not at all a new one as it has existed for centuries, and sometimes it is even dated back to the Roman Empire and Ancient Greece. Some people even consider graffiti as an act of terrorism which is in its larval stage. The main problem with graffiti is that it is fundamentally unauthorized and is created by destroying someone’s possessions.

Today graffiti vandals use markers and spray paints as their most common medium for creating graffiti which makes it a much bigger problem. Painting over the graffiti is a costly affair which the owners of the property vandalized have to bear. Graffiti makers tend to remain unknown and thus, never even make an offer to pay for the repairs for vandalizing someone’s property which at times could even be thousands of dollars.

Sometimes due to graffiti a property’s value gets lowered by a huge rate due to some inane scribbling across the wall or fence of the property. Not only do these graffiti vandals scribble on the fences and walls of the property they sometimes even destroy them by breaking a window, door or fence just for the mere sake of art. They slash the seats of the cars, buses and trains for which the government has to pay. (Ley, 491-505)

Recent History

In the last few decades the problem of graffiti has become far reaching and has spread from the largest of cities to small localities. Graffiti should not be viewed as an isolated problem since it leads to other public disorders, like loitering, littering and even public urination, and crimes, since most of the time the graffiti scribblers unable to pay for the markers and paints shoplift the required materials. Since graffiti is considered to be a public disorder it is sometimes even perceived as a means of lowered quality of living in certain communities.

As graffiti is almost always associated with crimes, it tremendously increases the fear of various criminal activities among the families of a community. Sometimes graffiti vandals even arouse questions in the hearts of the citizens by making them feel that the government authorities are incapable of protecting them from graffiti scribblers, thus making them further insecure.

Graffiti vandals have no concern for public or government property near public areas and deface anything they can lay their hand on including blank walls, trees, alley gates, monuments, statues, utility boxes, schools, furniture in parks and streets, buses and bus shelters, pavements, railway areas, utility poles, telephone boxes, street lights, traffic signs and signals, inside and outside of trains, vending machines, vacant buildings, freeway, subways, bridges, billboards, parking garages, sheds and road signs.

In a nutshell, graffiti is present almost in any area that is open to the view of the general public. Since graffiti vandals even mess with street signs and traffic signals that help the drivers navigate through busy towns, graffiti poses a threat to the safety of those drivers. Sometimes due to depreciation in land value or excessive nuisance created by these graffiti vandals, families and businesses alike have to avoid certain areas and may even have to move out of it completely. People facing graffiti vandalism and living in areas with graffiti have to face reduced business activities since common people generally associate criminal activities with graffiti and are thus, afraid to set up businesses in those areas. (D’Angelo, 102-109)

Cost of cleaning

Prevention and cleaning up of graffiti is associated with high costs. The government and the public have to bear heavy costs in order to protect themselves from the graffiti vandals. Currently, it had been estimated that almost $22 billion is spent in the US each year for cleaning up and preventing various acts of graffiti. It was also found that England almost has to spend £26 million every year to remove graffiti which is present in almost 90% of the places in the nation.

It becomes the headache of the local authorities to clean up the graffiti and fix whatever has been destroyed as soon as possible. Councils and government officials have to maintain quick responsive units who can rapidly and effectively clean out graffiti and fix damages the instant such an act is reported. Government authorities and councils even have to take up a combination of protective, preventive and removal strategies to fight back graffiti vandalism, making the whole process extremely costly. But since protecting or deterring property will not completely eliminate graffiti, it is better to remove graffiti as soon as it is reported. (Ley, 491-505)

Negatives of Graffiti

Graffiti not only causes danger to the citizens of a neighborhood but it also creates a huge mess which government officials have to clean up by paying from the city funds. Since the government has to bear the cost for cleaning up graffiti, it has a direct impact on the budget of a city too. Government officials have to use a significant amount from the available city budget for fixing damages to public buildings, streets and other properties. A huge amount of money also goes in the eradication and prevention of graffiti vandalism since this requires special equipment, materials and trained labors, making the entire matter highly expensive and time consuming.

Graffiti also adversely affects the taxpayers who have to pay extra for fixing damages to public properties, circuitously, during their yearly property taxes. Sometimes businesses pass on the cost for cleaning graffiti off their property on to their customers, who have to make larger payments for their goods purchased, for no fault of theirs. (Rafferty, 77-84)

Further, graffiti also causes losses in revenues related to reductions in retail sales and the transit systems. Thus, the money that needs to be spent for cleaning up and preventing graffiti can also be used for improving an area and may also have other valuable uses. Since graffiti contributes to a reduction in retails sales, businesses plagued by graffiti is least likely to be sponsored by others. Also the general public will be afraid and will feel unsafe when entering a retail store scrawled all over with graffiti. Graffiti vandalism is not always simply limited to spray painting and destruction of property since the graffiti vandals often commit severe crimes like rape and robbery. Given that they are not caught or reported most of the times, graffiti vandals think that they can do anything and get away with it. (Austin, 450-451)

Graffiti is frequently associated with gangs, although graffiti vandals are not limited only to these gangs. It creates an environment of blight and intensifies the fear of gang related activities and violence in the heart of the general public. It has been seen that gangs often use graffiti as a signal for marking their own territory and graffiti also functions as a tag or indicator for the various activities of a gang. In those areas, where graffiti is extremely common, tag and gang graffiti is extremely widespread and also causes a lot of trouble.

Gangs commonly make tags using acid spray paints or markers on apartments and buildings and they serve as a motto or statement or an insult. Such graffiti also include symbols and slogans that are exclusive for a particular gang and may also be made as a challenge or threat for a rival gang. Not only are graffiti made to disrespect other gangs but sometimes racist graffiti is also scribbled on walls which creates a lot of racist tension among the people of certain communities.

Such activities shock the residents who are indirectly forced to move out of the areas for the safety of their families. Graffiti scribblers who are also members of a gang or part of its crew sometimes get involved in fighting, and every now and then a number of them end up dead due to these gang wars. The messages relayed through graffiti are taken very seriously by gang members and the threats are almost always acted upon. (Smollar, 47-58)

Another problem with graffiti is that although sometimes a single act of graffiti may not be a serious offence, graffiti itself has a cumulative outcome which makes it even more serious. Its original emergence in a particular neighborhood almost always attracts even more graffiti vandals. At certain areas graffiti tend to occur over and over. Graffiti offenders are inclined to attack those areas that are painted over to clean the graffiti. Such areas act as a magnet attracting graffiti offenders to commit re-vandalism repeatedly.

Some graffitists commit acts of vandalism since they are extremely stubborn and do so in order to fight an emotional and psychological battle with the city council and government officials. They deliberately commit graffiti vandalisms in order to establish their authority and claim over a specific area. Graffiti offenders do so with the intention to defy the government authorities. (Wilson, 52-66)

Sometimes graffiti is extremely repulsive and thus, gets people, especially teenagers into extremely bad habits. They stop caring about other people or the government and develop a tendency to scribble anywhere they find a blank space. They stop respecting people and their property and the kids even start to make graffiti on the desks and tables of their schools. Graffiti vandals have no concern for the people around them and thus, increase the pessimistic attitude of the neighborhoods around them.

Not only does graffiti lead to crimes but the scribblers also harbor disruptive anti-social feelings and behavior inside them. Sometimes teenagers and kids place graffiti on other people’s property without their authority or consent as a mischievous act, not realizing that they are committing a crime which is equivalent to vandalism and punishable by law. These juvenile scribblers are accountable for almost all of the graffiti we find on the buildings and streets and they do not even realize that their graffiti sometimes even becomes offensive and racist in nature. (Rafferty, 77-84)

Juvenile crime

City officials are also concerned about the fact that when juveniles take part in graffiti vandalism it may be their initial offence leading them into much more harmful and sometimes even sophisticated crimes. Not only does graffiti create a gateway for these juveniles into a world of crime, it can sometimes also be associated with truancy due to which the juveniles may remain uneducated their whole lives.

Deprived of a proper education these young minds get involved with alcoholism and drug abuse, thus leading to even severe problems. Adolescents and juveniles become astray sending a message to all that graffiti give rise to various criminal activities. In those communities where people gather in groups at street corners during late hours, it is easier for the drug peddlers to promote their products among the juveniles without being interrupted either by the authorities or residents. (Smollar, 47-58)

Graffiti as a Social menace

Graffiti is a huge problem since it contaminates the environment of a locality. It is undeniably a plague for our modern cities since it leads to visual pollution. City officials and councils have to spend huge sums in order to clean the ever present graffiti on the walls and fences. But even an expensive cleaning strategy is not but a useless and ineffective way to deal with these graffiti vandals since they almost always find a way to reproduce graffiti.

Graffiti vandalism is an extremely complex and multifaceted public disorder which does not have any easy solution. Not only is the cleaning of graffiti an expensive affair, it is also an extremely difficult one since it involves a lot of hard work. Sometimes graffiti damages certain surfaces to such an extent that they remain permanently impaired as the graffiti vandals change the entire nature of the surfaces they paint on, thus changing the nature and environment of the whole neighborhood. If an act of graffiti vandalism is left unchecked, then it may even lead to urban decay by causing further decline in property value and increasing fear in communities.

Most of the times when graffiti is cleaned or painted over a part of the damage always remains. For example, the paint does not match entirely or sometimes the area becomes darker than before, making the cover up completely visible. Graffiti has a significant impact on the overall appearance of a neighborhood and almost always lowers the quality of life of the entire community. When these graffiti scribblers destroy train terminal and subways they immediately create a harmful first impression on others, of that city, all over the country.

Graffiti simply does not give rise to maintenance issues but it gives rise to a complicated social problem, one that makes people feel extremely unsafe in their own neighborhoods. Communities become unlivable due to reduction in the beauty and pride of their neighborhood. Graffiti completely destroys the design and scenic beauty of the entire community and the hate messages conveyed through graffiti hurts the people of the community.

Sometimes graffiti becomes so offensive that it disturbs the local residents making it a concern for the entire community. The residents not only feel unsafe themselves but also fear for their children who have to grow up in such a disturbing and troublesome locality. Though graffiti may appear to be a radical form of art, to the people whose belongings have been disfigured by graffiti it is nothing more than an unwanted form of vandalism, which is not only distressing but also extremely difficult to remove. (Rafferty, 77-84)

Consequences of Graffiti

Since defacing of public or government property without the owners authority is considered to be vandalism, offenders are even punishable by the law of many countries. Graffiti is like a crime since its creators steal the rights of the owners of the property to have their possessions look well and clean. Police authorities all over the world refer to graffiti vandalism as criminal damage. Graffiti vandals should be made to face strict penalties which should not only include jail time but also large fines, so that they do not repeat their actions again. The offenders not only have to pay huge penalties but can even be prosecuted for their crimes.

The graffiti vandals should not only have to pay fines for destroying properties but should also be made to clean the graffiti themselves, as a punishment. Juvenile scribblers have to carry out community services as a punishment for their crime. Graffiti vandals who have committed serious crimes, like rape or murder can even be imprisoned for life. Not only do these graffiti vandals damage other people and government properties, they also risk their own lives in making the graffiti. They often display their stupidity by gambling with their lives while trying to create graffiti on trains and bridges. It has often been seen that these graffiti scribblers suffer from dreadful injuries and some even end up dead. (D’Angelo, 102-109)

Some countries do not view graffiti as a major problem since they may not have encountered widespread incidences of graffiti vandalism, which may have been focused on only a few relatively hot spot areas. But the areas facing the problem of graffiti vandalism realize its intensity. Since graffiti is a highly visible form of vandalism, it greatly affects the people living in that area since it completely changes their existing perception of the entire neighborhood.

Graffiti scribblers carefully choose those locations frequented by passersby so that they can be affected by the drawings and scribbling even more. Graffiti becomes a form of vandalism due to the medium the graffitists use to display their art which is almost anything other than a piece of canvas. Graffiti vandals somewhat force the viewers to view their work, even if they do not want to do so.

They have no consideration as to where they place their work or that it may become a problem for the general public or that the medium which they are using either belongs to the government or to an individual. All these add up to people’s perception which views graffiti as vandalism leading to urban decay and crime and causing depreciation of business and property value and in the growth of industries.

Works Cited

Austin, J. “Wallbangin’: Graffiti and Gangs in L.A.” American Ethnologist 29.2 (2004): 450-451.

D’Angelo, Frank J. “Fools’ Names and Fools’ Faces are Always Seen in Public Places: A Study of Graffiti.” Journal of Popular Culture 10.1 (2006): 102-109.

Ley, D. “Urban Graffiti as Territorial Markers.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64.4 (2001): 491-505.

Rafferty, P. Discourse on Difference: Street Art/ Graffiti Youth.” Visual Anthropology Review 7.2 (2005): 77-84.

Smollar, J. “Homeless Youth in the United States: Description and Developmental Issues.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 39.5 (2006): 47-58.

Wilson, J. “Racist and Political Extremist Graffiti in Australian Prisons, 1970s to 1990s.” The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 47.1 (2008): 52-66.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, October 29). Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism? https://studycorgi.com/graffiti-is-it-art-or-vandalism/

"Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism?" StudyCorgi , 29 Oct. 2021, studycorgi.com/graffiti-is-it-art-or-vandalism/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism'. 29 October.

1. StudyCorgi . "Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism?" October 29, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/graffiti-is-it-art-or-vandalism/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism?" October 29, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/graffiti-is-it-art-or-vandalism/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism?" October 29, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/graffiti-is-it-art-or-vandalism/.

This paper, “Graffiti: Is It Art or Vandalism?”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: October 29, 2021 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Vandalism or art? Graffiti straddles both worlds

By Jean Reichenbach | March 1991 issue

- UW Magazine Facebook

- Jump To Comments

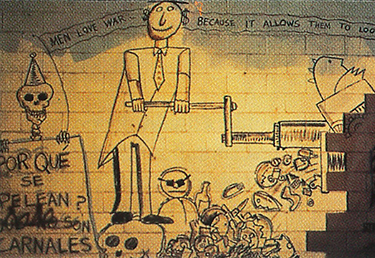

K ilroy was here ... and there ... and everywhere. Anyone old enough to have experienced the American landscape between 1942 and 1956 remembers that Kilroy left his name on rocks, bridges, buildings and—during World War II and the Korean War—even on walls behind enemy lines.

Kilroy may be history but today, in America’s inner cities, there are still graffiti scrawls “behind enemy lines.” Some gang graffiti serves as a billboard announcing to streetwise cognoscenti that “I sell drugs here” or “I shoot people who don’t belong here” or a warning that “You are passing into enemy territory.”

Other gang-related scrawls are simply expressions of a basic adolescent urge to establish groups and set goals. A list of names or nicknames (called “tags” in graffiti culture), for example, may simply mean “We hang out together,” says a UW expert in graffiti.

Whether it’s Kilroy’s name or a gang member’s “tag,” the writers are exercising one of graffiti’s most important functions: providing people with little access to other means of public expression the opportunity to be heard, explains Rick Olguin. An American ethnic studies professor, Olguin became interested in the subject as a graduate student at Stanford University and is now writing a book about graffiti.

A 1976 photo shows both Anglo and Hispanic anti-war graffiti.

Actually, G.I.s and gang members are relative latecomers to this ancient medium of communication, protest and occasionally genuine art. The catacombs under the city of Rome, for example, bear names and symbols left by persecuted first century Christians.

Olguin describes visiting a ruin in Greece where one of the now-scattered building blocks bears a mark scratched into it by a stonemason 3,000 years ago. “At that moment something really clicked about this universal urge to write graffiti, or for people to write their initials in fresh cement or carve their name in a tree or a desk,” he recalls. “Fundamentally, graffiti is almost the universal way in which people express a fairly universal drive to be remembered.” And because it represents a universal human desire, Olguin deplores society’s tendency to “trivialize ” modern graffiti by “collapsing all of it into gang behavior.”

Olguin’s views notwithstanding, Sue Honaker, Seattle’s anti-graffiti coordinator, doesn’t hesitate to label as “graffiti vandals” the people who decorate walls that don’t belong to them.

Honaker can’t estimate how much graffiti removal costs the city of Seattle each year. But, she points out, the Seattle Public Library one year spent half its annual maintenance staff hours removing graffiti and Metro spent “well over $500,000” in one year cleaning graffiti from buses.

New York City spends $52 million annually in the battle against graffiti on its more than 6,000 subway cars, according to U.S. News and World Report . Last year, Time reported that annual U.S. costs run “into the billions.” Jay Beswick, founder of the National Graffiti Information Network, said in the same report that Los Angeles spends $28 million annually dealing with graffiti and Southern California cities together incur costs of $100 million.

“ It's not a question of art. It could be the Mona Lisa, but if it's on the side of your house, your rights are violated. ”

Sue Honaker, Seattle's anti-graffiti coordinator

“Basically, graffiti is any scrawl, writing, picture or marking on someone else’s property without their consent,” says Honaker, a 1984 UW alumna. “I don’t think there’s a person alive who has a problem with art,” she adds. “It’s not a question of art. It could be the Mona Lisa, but if it’s on the side of your house, your rights are violated.”

Olguin agrees that graffiti that encourages criminal behavior should be obliterated. But, he adds, society often fails to recognize that graffiti can also be art and a serious expression of cultural roots. “Not quite as complex as Navajo blanket weaving, but it has that kind of characteristic.”

Among Puerto Rican youth in New York City, for example, a master graffiti painter will draw out the mural and a group of apprentices, many of whom aspire to master status themselves, complete the project under his direction, says Olguin. “They’re seriously involved in learning a cultural aesthetic form of representation. It’s not just pure vandalism. … It’s art school just like Rubens.”

Olguin also ties graffiti to what he calls the “aesthetic of no empty space ” found in many cultures around the world. The walls of whole villages in remote parts of West Africa are painted in mural fashion, he says, and traces of these traditional motifs can be identified in African-American graffiti. “If these (African village) people occupied these offices,” he notes with a gesture toward the pristine perimeter of his Padelford office, “none of these walls would be white.”

Graffiti style makes its way into the mainstream in the lettering of this Chicano preschool sign.

The same aesthetic of filling empty space is also characteristic of pre-Columbian cultures. Walls in the ancient city of Teotehuacan, which 1,200 years ago had a population of 100,000, were entirely covered in floral murals, Olguin observes. Pre-Columbian designs, such as the feathered serpent or the step-pyramid shape, can be found today in graffiti in Mexican-American sections of cities such as Los Angeles and Albuquerque.

Olguin also ties the psychological mechanisms behind graffiti to the practice of ritual scarification (including the up-to-date “ritual scar” of pierced earlobes). He also likens it to tattoos (which he calls “personal permanent graffiti”), and even the current craze for message-bearing T-shirts, which are “thoroughly painless and another place you see all kinds of graffiti.” All of those practices, he says, reflect a deep human need to control our surrounding space.

Honaker, whose view is less academic, divides the graffiti she sees into several categories, including bubble gum (“John Loves Mary”), religious (“Jesus Saves” or “Allah Saves”), political, cartoon, gang and satanic which, she adds, is sometimes accompanied by evidence of animal mutilations such as a beheaded cat.

Each type of graffiti tends to have its own symbols. Satanist and white supremacist graffiti may be accompanied by the names of heavy metal rock ·bands such as Black Sabbath, Guns and Roses, Metallica and URU, Olguin notes. The pentagram, a five pointed star within a circle, is also a satanist symbol.

Disembodied heads are another common graffiti motif, Olguin notes, of which Kilroy, with his head and hands showing above a horizontal line, is a prime example. Chicano youth currently favor a front-view face with a goatee and perhaps a mustache, sunglasses and a fedora. Sculptors have been making disembodied heads for centuries whenever they create busts, Olguin points out. “It’s sort of canonical.”

One mysterious symbol that has cropped up in Seattle recently is a “weird squiggle,” in Olguin’s words, that at first glance suggests an Asian language. But experts at the Jackson School of International Studies have not been able to identify it. Sometimes, upon close inspection, the images resemble Roman letters elaborated almost to the point of being illegible, much like some of the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, notes Olguin, who remains mystified about what the messages signify or who is writing them.

A 1990 mural in Albuquerque, New Mexico, painted to discourage drug use, employs street graffiti styles.

Contemporary writers of political graffiti have adopted 19th century anarchist symbols such as a black flag or the letter A inside of a circle, Olguin notes, although he doubts they understand classic anarchist philosophy. “To them, anarchy means ‘There are no rules,’ which is different from ‘There is no government,’ which is what anarchy is about.”

As is often the case in popular culture, California can be a trendsetter in graffiti. Corporate symbols, such as the familiar bell of the telephone company, the logo of the Los Angeles Raiders, or oil company logos are popular territorial markers for Los Angeles gangs, says Honaker. “El Norte” and “El Sur” are gang designations seen throughout Northern and Southern California respectively. Such designations, including the gang names Bloods and Crips, tend to make their way north. One of Olguin’s friends has seen the word “Surrenos” in a neighborhood in West Seattle, the mark of a group of kids from a neighborhood in southern Orange County.

In contrast to some cities, Honaker notes, only about two percent of Seattle’s graffiti is the work of true gang members. Olguin agrees that the percentage is small. Most gang-type work is “copy cat,” in Honaker’s words, but she declines to make public the clues that allow her to tell the difference.

If gang graffiti is an expression of “I belong,” hate graffiti is a statement of separation, Olguin says. “You get a real statement of identity, not through connection to a space but through definition of an outgroup: ‘I am not gay’ … ‘I am not black’ … ‘I am not woman.”‘

The campus has seen a recent “flurry of really ugly racist stuff,” says Anne Guthrie, administrative manager in the UW’s facility management office. Guthrie ties the wave to a resurgence of racism both here and on American campuses in general. Official policy calls for the prompt removal of all graffiti, says Guthrie, but special efforts are made to remove racist and sexist scrawls within 24 hours.

A mid-1970s mural in San Diego that promotes the United Farmworkers has not been defaced by graffiti in more than 10 years.

Political graffiti is also popular on campus, and is usually aimed at political and military hot spots from El Salvador to the Middle East. Favorite locations seem to be the west wall of campus facing 15th Avenue N.E., the back wall of Kincaid Hall near the Burke Gillman Trail and “Red Square” near the Odegaard Undergraduate Library, Guthrie says. The stairwells from the Central Plaza Garage are another popular target.

To Guthrie’s knowledge, no tally is kept of how much money and staff time is spent removing campus graffiti. But, she points out, in an era of limited budgets, every dollar or hour devoted to graffiti removal is that much less available for other, badly needed, purposes.

Removal techniques and costs vary according to the surface and the kind of paint used. Concrete can be painted over, cleaned with high pressure water hoses or sprayed over with what Honaker calls a “slurry” that, in effect, applies a thin layer of new concrete.

Brick and marble surfaces are especially expensive to clean, Honaker notes, and often require the use of chemicals which pose an environmental threat when they make their way through storm drains into rivers or other bodies of water.

Like Olguin, Honaker spends considerable time on the street getting to know the youth who engage in the graffiti. She tries to “stay away from the punitive” and works hard to maintain good relationships with known graffiti vandals who keep her up to date on “what’s new on the street,” she says.

Her experience leads her to believe that graffiti vandalism is an essentially anonymous behavior which permits individuals to, in her words, “rile without risk.” Youngsters who have failed to attract approval through academic, social or athletic achievement can, through graffiti, command a moment in the sun, she notes. Take, for example, the New York City youth who slipped into a zoo at night and spray-painted graffiti on the back side of an elephant. “He had a good story to tell at school the next day,” Honaker notes.

Most youthful vandals are from the lower economic levels, Honaker says, but the activity also attracts affluent children who “put up graffiti or run with a tag team” as a way to add a sense of risk to otherwise orderly, safe lives. A “tag team,” she explains, often consists of an artist, a lookout, and someone adept at stealing paint—which can be a major undertaking and is often a point of honor in itself. “A good piece can take as many as 500 spray cans,” she adds.

Whenever possible Honaker tries to persuade the best of the painters to design and paint murals on walls offered for that purpose by Seattle business people. The city already boasts dozens of such productions.

“There’s a lot of really good talent out there,” she notes. “Good people who are misdirected.”

Olguin urges that we work harder to re-channel not just the art but also the energy of the youths who participate in it. These youngsters, with their graffiti and gang behavior, are exploring the limits of society’s rules, he notes. “It seems to me that (exploring these limits) is what entrepreneurial societies are all about, what aesthetically creative and dynamic societies are all about.”

At top: A 1990 photo of a retaining wall on Rainier Avenue South in Seattle that is covered with hundreds of “tags.”

Jean Reichenbach is associate editor of Columns.

Be boundless

Connect with us:.

© 2024 University of Washington | Seattle, WA

Advertisement

Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2015

- Volume 22 , pages 107–125, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gabry Vanderveen 1 &

- Gwen van Eijk 2

54k Accesses

23 Citations

50 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Annoying paintings everywhere, [it] should be forbidden, and the perpetrators [should] clean everything with a toothbrush. It is pollution. There is an exception, what happens in cities, a boring wall is embellished with a nice painting made by experienced professional artists.

Introduction

The citation above, of a participant in our study who describes his first image of graffiti that comes to mind, summarizes our argument: public opinions on disorder (graffiti, in this case) may vary considerably, not only between people but people themselves make different judgments, depending on what they see in which context. Indeed, studies prove that ‘graffiti has been called everything from urban blight to artistic expression’ (Gomez 1993 : 634). Lombard ( 2012 ) calls graffiti ‘art crimes’ because it is criminal and artistic at the same time, which makes it also difficult to distinguish ‘artists’ from ‘criminals’. Even graffiti writers recognize that graffiti, while for them in the first place art, in some contexts is damaging or inappropriate (Rowe and Hutton 2012 ). According to Brighenti, graffiti is an ‘interstitial practice’: a practice about which different actors hold different conceptions, depending on how it is related to other practices such as ‘art and design (as aesthetic work), criminal law (as vandalism crime), politics (as a message of resistance and liberation), and market (as merchandisable product)’ ( 2010 : 316). A response to an interstitial practice always comes in a ‘yes, but’ form: graffiti is crime, or art — but it is always also something else (ibid.). Therefore, White ( 2000 : 253) argues, we should not condemn, nor celebrate graffiti, without considering ‘the ambiguities inherent in its various manifestations’.

Graffiti comes in many forms, varying from tag graffiti to artistic pieces and stencil art, and from illegal sprayings on public or private property to murals on legally designated walls. Our perspective is that there is no clear-cut distinction between graffiti and street art and that definitions based on form (e.g. tag, mural) cross legal definitions — the works of the (in)famous writer Banksy illustrate this point (Banksy’s work is often illegal but his work has also been sold and has featured in exhibitions, for example alongside Andy Warhol). Graffiti can be problematic, but not all graffiti is. The question as to when and why which forms of graffiti are perceived as criminal and by whom, remains an open question.

Yet, authorities, and many criminologists as well, tend to see graffiti as an unambiguous signal of disorder or even crime. Informed by the broken windows theory, many local governments seek to prevent and remove graffiti (e.g. Snyder 2006 ; Young 2010 ; Kramer 2010a ; Tempfli 2012 ; Uittenbogaard and Ceccato 2014 ). Studies in the tradition of the broken windows theory and social disorganization theory seem to assume that the public more or less agrees on what phenomena are ‘disorder’, and graffiti would be one of such phenomena. In this line of argument, ‘disorder’ would trigger fear (Ross and Jang 2000 ; Xu et al. 2005 ), undermine collective efficacy (Sampson et al. 1997 ; Kleinhans and Bolt 2013 ) and invite crime (Wilson and Kelling 1982 ; Wagers et al. 2008 ).

Our study engages with and critiques this line of argument in two ways. First, we observe that there has been much less attention for diverging (and conflicting) interpretations among the public. Many studies point at the mismatch of interpretations of graffiti as either art or crime between writers on the one hand and authorities, (supposedly) reflecting the concerns of the public, on the other hand (Whitford 1991 ; Gomez 1993 ; Halsey and Young 2006 ; Millie 2008 ; Snyder 2006 ; Dickinson 2008 ; Edwards 2009 ; Lombards 2012 ; McAuliffe 2012 ; Young 2012 ; Haworth et al. 2013 ). Indeed, we would expect that the perspective of graffiti writers differs from the perspective of the public (Brighenti 2010 ), as the underlying meaning and subcultural codes of graffiti are unknown to the average street user (Ferrell 2009 ; Young 2012 ). It is assumed that the uninformed public, as well as authorities and media, cannot distinguish one form of graffiti from another, thus interpreting all graffiti as evidence of increased gang activity, young people’s disrespect for authority or a threat to property values and neighbourhood safety (Ferrell 2009 ). However, in our study we show that opinions on disorder also vary significantly among the public. Based on qualitative and quantitative data we empirically unravel the different viewpoints on graffiti of the public in the Netherlands. Here we build on Millie’s ( 2011 ) work on value judgments in relation to criminalization.

Second, we elaborate insights on the role of context by examining judgments of graffiti in various micro places . Quantitative studies have generally examined context by focusing on the role of neighbourhood characteristics such as crime levels, population composition and stigma (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Franzini et al. 2008 ). We take a different approach and build on knowledge from mostly qualitative studies on context-related expectation and norms (e.g. Dixon et al. 2006 ; Cresswell 1996 ; Millie 2008 ). These studies draw our attention to the ways in which norms and expectations are tied to specific places, which together construct the meaning of places and of elements, such as graffiti, in those places. Using quantitative data, we investigate whether these ideas hold among a larger population (i.e. the Dutch public).

Studying responses to graffiti has broader relevance for research and policies on disorder, as graffiti is part of a larger ‘grey area’ of deviant behaviour that is not obviously criminal or harmful but nonetheless often labelled as ‘disorder’ (e.g. loitering, skateboarding, public drinking, noise). For example, following Jane Jacobs’ ( 1961 ) argument about the role of ‘eyes on the street’ in multifunctional neighbourhoods, people’s presence in the streets could contribute to safe street life and attract more people, but currently there is a tendency to see people hanging around in urban spaces as ‘social disorder’ (e.g. Ruggiero 2010 ; Binken and Blokland 2012 ). The same goes for public drinking: often banned in public space, but also tolerated when it contributes to the ‘aesthetic of the night-time economy’ (Dixon et al. 2006 ; Millie 2008 ). Particularly in the context of zero tolerance policies towards disorder, anti-social behaviour and incivilities, it is important to understand why and when behaviour is something that needs to be prevented, removed or punished. Critics of zero tolerance policies warn that in public space only certain behaviours from certain people are tolerated, while everything that deviates from the ‘mainstream’ is removed or excluded (e.g. Mitchell 2003 ; Beckett and Herbert 2008 ; MacLeod and Johnstone 2012 ). Diverging perspectives on disorder, graffiti included, lead to confusion about appropriate policy responses: if offensiveness is subjective, how can authorities discern what is acceptable and what is not? And to whom should authorities listen: to the majority, to those with most political or economic clout, or to more marginal groups who seem to struggle to enact their right to the city (Millie 2011 ; Kramer 2010a )? We return to these questions in the discussion. Before presenting our data, methods and results, we briefly discuss current trends in graffiti policy and criminological research on graffiti.

Graffiti as Art and/or Crime: Policy and Criminology

Even though ‘tough on graffiti’ approaches still dominate policies in countries such as Australia, the Netherlands, the UK and the US, the idea that the public responds in different ways to graffiti seems to be trickling down into policies, at least in some countries and cities. Repressive policies are concerned with preventing and removing graffiti, for example through applying special coatings and quickly removing all graffiti (e.g. Tempfli 2012 ; Uittenbogaard and Ceccato 2014 ). However, authorities have limited resources and thus need to prioritize which graffiti to remove first, which requires them to distinguish different types of graffiti (and for instance target offensive graffiti first, see Taylor et al. 2010 ; Vanderveen and Jelsma 2012 ). Moreover, local and national authorities do seem to distinguish between graffiti as a form of art and graffiti as crime, through mixing preventative and punitive measures with offering designated spaces for authorized graffiti (Kramer 2010b ; Lombard 2012 ; McAuliffe 2012 , 2013 ; Young 2010 ; Tempfli 2012 ). In some cities, graffiti (i.e. murals or pieces) is even used to prevent graffiti (Craw et al. 2006 ). Unwanted graffiti is in this way prevented and graffiti writers are offered alternatives. A bifurcated approach like this builds upon the idea that not all graffiti is received in the same way.

More generally, the way in which policy makers and citizens think about cities and a liveable urban environment is changing. Recent urban development seems to influence viewpoints on graffiti. Particularly the ‘creative city’ discourse offers opportunities to rethink the value of the creative practices of graffiti writers (McAuliffe 2012 ). Since Florida’s ( 2004 ) ‘recipe’ for successful cities (the 3 T’s in short: Technology, Tolerance and Talent — the latter T is measured by the share of people working in the creative sector), urban governments have promoted creativity in all forms and places to make their cities attractive. Indeed, in some places, graffiti in the form of murals is desired by policy makers to beautify locations and attract tourists (e.g. Millie 2011 ; Koster and Randall 2005 ; Zukin and Braslow 2011 ; McAuliffe 2012 ). However, city marketing may also result in a ‘get tough on graffiti approach’, as was the case in Melbourne in response to the run-up to the Commonwealth Games to be hosted in Melbourne in March 2006 (Young 2010 ). In London, authorities first painted over graffiti that mocked the Olympic Games and corporate sponsors, but recently commissioned graffiti as part of the Canals Project for East London’s waterways (Wainwright 2013 ). Such developments do not necessarily demonstrate a greater leniency towards graffiti. In the words of street artist Mau Mau: ‘when it suits them, they [the Council] choose who paints where’ (ibid.). So even when we may find that authorities are rethinking the meaning of graffiti, this is not necessarily applied to all graffiti in all places, which underscores our point that we need to consider responses to graffiti in relation to its form and context.

Given the ambiguity in how authorities deal with graffiti, we think it is striking that the dominant approach in criminological research on disorder views graffiti unambiguously as a social problem: something threatening that must be prevented and dealt with because it would cause fear and (more) crime. This idea is most common in studies following the ecological tradition (social disorganization theory) or the broken windows theory. Within ecological research, graffiti is often taken as an example of physical disorder (although it may also be seen as social disorder, see Skogan 1990 ), similar to other signs of physical disorder such as boarded-up houses, rubbish on the street and defaced bus stops. For example, in Wyant’s ( 2008 ) study on perceived incivilities and fear of crime, respondents were asked to indicate on a 4-point scale whether they thought various ‘neighbourhood problems’ capturing ‘perceived incivilities’ were a ‘serious problem’ in their neighbourhood, one of which is ‘graffiti on sidewalks and walls’ (see also, with varying questions or items: Ross and Jang 2000 ; Markowitz et al. 2001 ; Foster et al. 2010 ; Paquet et al. 2010 ; Gainey et al. 2011 ; Kleinhans and Bolt 2013 ).

Moreover, the broken windows theory suggests that graffiti and other signs of disorder in neighbourhoods cause not only fear but also crime, because fear would weaken social control and thus signal opportunities for crime to motivated offenders (Wilson and Kelling 1982 ; Wagers et al. 2008 ). A rare test of the assumed causal link between perceiving disorder and crime is the study of Keizer and colleagues ( 2008a ) which suggests that when people see norm transgression they are more likely to overstep a rule themselves. In one of the six field experiments, they demonstrate that in an environment with tag graffiti on a wall, people are more likely to litter, compared to a clean environment. However, Keizer and colleagues tested only for tag graffiti. They did consider different types of graffiti for their research design and decided on ‘simple tags as the more elaborated “pieces” might be perceived as art instead of norm violations’ (Keizer et al. 2008b ). However, while Keizer and colleagues acknowledge that different types of graffiti are valued differently, they still seem to assume that tag graffiti (as opposed to pieces) is always a norm violation, thus disregarding the variety of meanings, also to the public, of graffiti. While the broken windows thesis is popular among policy makers around the globe, the idea that there is a causal link between neighbourhood disorder and neighbourhood crime has been criticized (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Harcourt and Ludwig 2006 ). It is indeed questionable when we consider that disorder is an ambiguous phenomenon. However, even studies that do distinguish different graffiti types (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 : tags, political and gang graffiti; Foster et al. 2010 : on public property and on private property; Perkins and Taylor 1996 : graffiti on residential and non-residential property) usually combine the different types with items such as vandalism and litter to construct a scale measuring ‘physical disorder’. Thus, all graffiti, regardless of type and location, is taken as disorder.