- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Consumer Health Information, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 690

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Consumer health literacy is an important component of modern healthcare practice because it enables patients to be proactive in understanding the issues that impact their health, as well as in recognizing how to best overcome personal health concerns that influence their own perspectives regarding health. It is important to recognize that many consumers who are tech-savvy may have a tendency to self-diagnose using various websites; however, this does not replace truthful and unbiased healthcare information comprised of the facts that is available from reputable sources. It is necessary for consumers to properly decipher and interpret health information effectively in order to identify areas where health information is lacking or is inappropriate in meeting patient needs.

Interpreting health information in the appropriate manner requires a high level of focus and an understanding of the different expectations that consumers have regarding information that is easily accessible on the web and in other locations (Goldberg et.al, 2011). In this context, consumers must be able to obtain health information that is accurate and timely, rather than to rely on information that is untruthful and outdated (Goldberg et.al, 2011). Health information must be properly evaluated and provide useful insight regarding health issues of concern that impact many consumers (Goldberg et.al, 2011). Consumers must also be receptive and willing to learn about health issues through skill development and literacy strategies to improve confidence in health information and in the experts who provide this information to the masses (Car et.al, 2011). These practices require expert knowledge and guidance in advancing health and in supporting preventative and proactive strategies to protect health through improved knowledge and awareness (Car et.al, 2011).

Patients must be adequately prepared to improve their health literacy and to seek out information freely regarding health topics; however, this practice must also take other factors into consideration, such as preventative education that is used to address primary health concerns (Car et.al, 2011). Health literacy is a lifelong phenomenon that requires an effective understanding of the different elements that attract consumers to this practice, such as information that is truthful yet relatively easy to understand (Schnitzer et.al, 2011). These practices require individuals to take the steps that are required to ensure they are health literate and possess knowledge of a variety of health topics from a honest and truthful perspective so that they are able to better understand their own issues more effectively (Schnitzer et.al, 2011). At the same time, it is important for consumers to develop an effective understanding of their needs and to be proactive in recognizing that health literacy is a critical factor in their own growth and maturity (Sheridan et.al, 2011). These factors require experts to educate others regarding health literacy and to be cognizant of the issues that may emerge that impact health knowledge in different ways (Sheridan et.al, 2011).

Consumers must be able to receive and comprehend health information in an effective manner, as this provides a greater sense of accomplishment and an understanding of the different elements that impact their own wellbeing. Health literacy is a lifelong process that requires health knowledge to be accurate and appropriate for consumers so that they are able to identify specific factors related to their own health. This practice also requires a long-term commitment to educating individuals across different age groups so that they are able to actively participate in making decisions regarding their own health that will have a positive impact on their lives throughout the life span.

Car, J., Lang, B., Colledge, A., Ung, C., & Majeed, A. (2011). Interventions for enhancing consumers’ online health literacy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev , 6 .

Goldberg, L., Lide, B., Lowry, S., Massett, H. A., O’Connell, T., Preece, J., … & Shneiderman, (2011). Usability and accessibility in consumer health informatics: current trends and future challenges. American journal of preventive medicine , 40 (5), S187-S197.

Schnitzer, A. E., Rosenzweig, M., & Harris, B. (2011). Health literacy: A survey of the issues and solutions. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet , 15 (2), 164-179.

Sheridan, S. L., Halpern, D. J., Viera, A. J., Berkman, N. D., Donahue, K. E., & Crotty, K. (2011). Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: a systematic review. Journal of Health Communication , 16 (sup3), 30-54.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Death of a Sales Man, Movie Review Example

Tips for Online Students, Research Paper Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Relatives, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 364

Voting as a Civic Responsibility, Essay Example

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Interviews

- Research Curations

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Submission Site

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Consumer Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, self-drivers, social drivers, solution drivers, service-provider drivers, societal/situational drivers, future directions, author notes.

- < Previous

The 5S's of Consumer Health: A Framework and Curation of JCR Articles on Health and Medical Decision-Making

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Szu-chi Huang, Leonard Lee, The 5S's of Consumer Health: A Framework and Curation of JCR Articles on Health and Medical Decision-Making, Journal of Consumer Research , Volume 49, Issue 5, February 2023, Pages 926–939, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac051

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Every day, consumers make decisions that have both direct and indirect impact on their health. The COVID-19 pandemic, and the long-term physical and mental complications that have ensued, underscores the importance of developing a holistic understanding of drivers of consumers’ health and medical decisions. Without this comprehensive approach, health appeals or interventions are destined to fall short of achieving positive and long-lasting outcomes. Beyond the pandemic, medical and biotechnological advancements can have greater impact on global lifespan when the behavioral sciences offer a critical, complementary lens to enhance the understanding, adoption, and implementation of these new technologies. By illuminating how consumers think, feel, choose, and behave in this multi-faceted decision environment, consumer researchers are well equipped to contribute to the ongoing quest to improve population health.

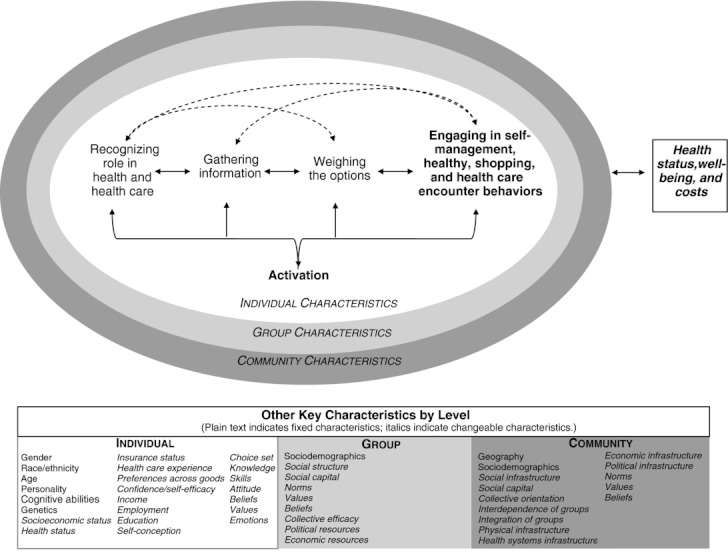

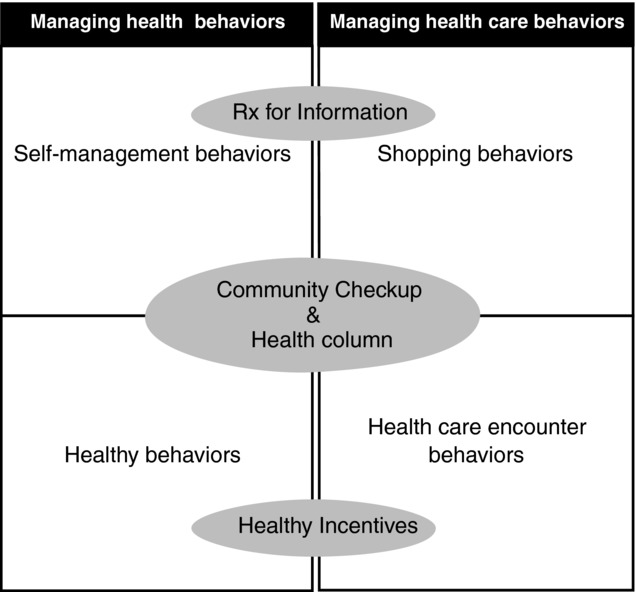

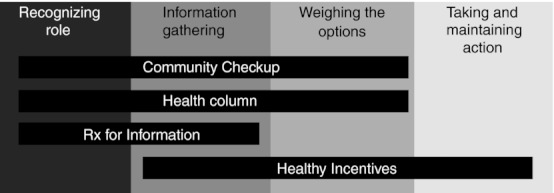

In this curation, we review many articles published in the Journal of Consumer Research ( JCR ) that focus on a spectrum of health and medical decisions, while highlighting five ( Bolton et al. 2008 ; Botti, Orfali, and Iyengar 2009 ; Briley, Rudd, and Aaker 2017 ; Longoni, Bonezzi, and Morewedge 2019 ; Moorman and Matulich 1993 ). We define consumer health and medical decisions broadly, as those relating to the prevention (e.g., minimizing stress, moderating alcohol consumption), diagnosis (e.g., utilizing health professionals for checkups), remedy and improvement (e.g., taking medication to cure an infection), and maintenance (e.g., monitoring dietary intake) of consumer health ( Moorman and Matulich 1993 ). We build on these articles to propose a new 5S ( S elf, S ocial, S olution, S ervice provider, S ocietal/ S ituational) framework to explain holistic drivers underlying consumers’ health and medical decisions ( figure 1 ). We hope that researchers will find this conceptual framework useful in structuring the existing consumer research literature on health. Furthermore, the 5S framework provides a clear set of four key directions that future researchers will find worthwhile in undertaking research on health and medical decision-making—either by delving deeper into the 5Ss or by going bigger and broader beyond the scope of past research.

THE 5S FRAMEWORK OF DRIVERS OF HEALTH AND MEDICAL DECISIONS

Many “self” variables drive health and medical decisions. Consumers belong to different demographic groups ( Connell, Brucks, and Nielsen 2014 ; Du, Sen, and Bhattacharya 2008 ) and have different health goals, abilities, perceptions, and beliefs. To pursue any action toward health, consumers have to believe that they can do it (i.e., self-efficacy) and that this action will lead to desirable outcomes (i.e., response-outcome expectancies; Bandura 1982 ); consumers’ perception of their own health abilities are thus critical ( Han, Duhachek, and Agrawal 2016 ; Keller 2006 ; Moorman and Matulich 1993 ). Consumers’ existing beliefs and perceptions about diagnoses and remedies are similarly important. For instance, consumers can hold different beliefs about healthy food ( Haws, Reczek, and Sample 2017 ; Raghunathan, Naylor, and Hoyer 2006 ), the accuracy and certainty of a diagnosis ( Wang, Keh, and Bolton 2010 ), and how effective a recommended remedy is ( Keller 2006 ). Consequentially, knowing that a remedy is highly effective can conversely lower consumers’ perception of risk, resulting in a boomerang effect on consumers’ pursuit of overall health ( Bolton, Cohen, and Bloom 2006 ). Below, we highlight three articles, including a focal article from this curation ( Moorman and Matulich 1993 ), that examined health motivation and health ability, self-efficacy and response efficacy, and consumers’ lay beliefs about remedies.

Health Motivation and Health Ability

Moorman and Matulich (1993) proposed a comprehensive framework to theorize how consumers acquire health information and what motivates consumers’ health maintenance behaviors, offering a thorough review of a large set of health models studying a wide variety of behaviors spanning from breast self-examination and nutrition labeling to AIDS information search. The authors propose two key constructs for understanding “self” drivers: (1) health motivation, defined as consumers' goal-directed arousal to engage in preventive health behaviors, and (2) health ability, defined as consumers' resources, skills, or proficiencies for performing preventive health behaviors. The article delineates a host of predictions including how health motivation promotes health behaviors, and how health knowledge, health status, health locus of control, health behavioral control, and demographic variables (education, [young] age, and income) will each promote health behaviors when health motivation is already high. Key among them is the idea that consumers must be motivated to pursue these health actions, and idiosyncratic differences in real and imagined health abilities can all contribute to the ultimate actions taken. Health motivation and health ability thus go hand in hand; policies and interventions that address only one self-driver and neglect the other will be leaving a lot on the table.

Self-Efficacy versus Response Efficacy

Keller’s (2006) influential article investigated successful health messaging and found a matching effect between consumers’ motivational orientation (i.e., regulatory focus) and their perceived effectiveness of a remedy (i.e., whether the remedy uses a self-efficacy or a response-efficacy appeal). For consumers who have a promotion focus, a self-efficacy message featuring an easy means toward a desired health state is more motivating; in contrast, for consumers who have a prevention focus, a response-efficacy message featuring an effective means toward a desired health state will be more motivating.

In one study, Keller recruited 61 students from a middle school. These students were primed to activate either a promotion or a prevention focus; they then saw a full-page sunscreen appeal: one side of the appeal displayed a picture of a young woman with half her face altered to show the negative effects of the sun; the other side of the appeal displayed either a self-efficacy message (“You can do it! It’s as easy as 1–2–3”) or a response-efficacy message (“Sunscreen Works! There is no better way”). The author found that when the students were guided to think about hopes and aspirations (i.e., a promotion focus), the self-efficacy message was more effective; but when the students were guided to think about duties and responsibilities (i.e., a prevention focus), the response-efficacy message worked better. This article highlights the importance of understanding consumers’ motivation orientations—whether they are more concerned about their own abilities or the remedy’s effectiveness in achieving the desired health state. Designing appeals for different motivational orientations goes a long way toward sustaining the effectiveness of these appeals.

Lay Beliefs about Remedy

In addition to health motivation and the perception of ability, consumers also have many existing beliefs about remedies and treatments that are available in the marketplace. Wang et al. (2010) examined the lay theories consumers hold about two aspects of medical decision-making—specifically, lay beliefs about diagnosis and lay beliefs about health remedies.

In a study with 100 Chinese college students, the authors directly manipulated how certain the diagnosis was and whether these students had a class presentation to make in 2 or 10 days. Consistent with the authors’ theory that consumers’ lay beliefs drive their preference for specific remedies, these participants preferred traditional Chinese medicine over Western medicine in all situations except for one condition: when diagnosis uncertainty was low and the class presentation was in two days, participants’ preference shifted toward Western medicine because of their lay belief that Western medicine has higher causal certainty and faster response efficacy.

These beliefs critically drive consumers’ desire to pursue a healthy lifestyle. The authors’ subsequent studies found that traditional Chinese medicine that attends to the whole body are less likely to backfire in the pursuit of a healthy lifestyle because these remedies acknowledge the interaction of treatment with the rest of the body and the mind. In contrast, Western medicine that emphasizes cause–effect sequences tends to narrow consumers’ focus and neglect other health-related actions, leading to a boomerang effect and decreasing consumers’ desire to engage in a healthy lifestyle. Here, the authors highlight the importance of understanding global lay beliefs about diagnosis and remedies so that healthcare practitioners can provide tailored recommendations that minimize backfiring and promote well-rounded health outcomes.

Consumers are social beings; not surprisingly, consumers’ health decisions are heavily driven by social forces. One particularly powerful way that social factors impact health is through social comparison. Other people in our social network serve as meaningful reference points, and we gain self-knowledge by comparing our situations to those of others ( Festinger 1954 ; Tesser 1988 ). For instance, consumers going through medical treatments can affiliate with others undergoing similar procedures for support and knowledge exchange. By assimilating with others who have successfully overcome a health challenge, consumers can feel more optimistic about their own chance of success ( Huang et al. 2015 ; Kulik and Mahler 2000 ). In addition to assimilation, consumers may contrast themselves against undesirable social groups to signal their own identity (e.g., consuming less food than the undesirable social group, McFerran et al. 2010 ). Furthermore, social comparison can either boost or discourage consumers’ adoption of innovative health solutions depending on whether consumers are holistic or analytical thinkers ( Chung and Lee 2019) .

The second powerful way that social others influence us is by sharing and altering our decision-making process ( Dzhogleva and Lamberton 2014 ; Fishbach and Tu 2016 ; Fitzsimons and Finkel 2010 ; Liu, Dallas, and Fitzsimons 2019 ). In the medical context, consumers’ decisions can not only be shared and shaped by others but can also be completely given or delegated to others—in these cases, social others go beyond merely altering our decisions but become the decision-makers themselves. Examples include parents choosing a treatment plan for their child, a person deciding whether to remove life support for their partner who is in a coma, or children choosing a personal-care provider for their aging parent. Below, we discuss these two broad categories of social forces by highlighting two articles, respectively, including one of our focal articles ( Botti et al. 2009 ).

Social Comparison

While assimilation can be easily observed in medical settings such as through various support groups at hospitals, it may be harder to imagine how consumers’ desire to contrast against undesirable social groups would affect their health decisions. Berger and Rand (2008) examined this social factor and leveraged it to increase life-benefiting decisions. They observed that undergraduates at Stanford University were reluctant to wear helmets because graduate students—a group the undergraduates did not identify with—wore helmets. The authors leveraged this insight to reduce risky behaviors such as alcohol consumption by highlighting how these behaviors were popular among out-groups.

In one field experiment, the authors posted flyers to promote responsible drinking in restrooms and on bulletin boards at two freshman dorms. At the treatment dorm, the flyer linked alcohol consumption with graduate students by depicting a graduate student holding an alcoholic beverage; the message ended with “Nobody wants to be mistaken for this guy.” At the control dorm, the flyers provided typical information about negative health effects of alcohol without evoking any social identity. Using follow-up surveys and self-reported alcohol consumption measures, the authors found an interesting interaction between the flyers and freshmen’s existing attitude toward graduate students (i.e., the out-group). For freshmen who did not want to be affiliated with graduate students, the treatment flyers created a strong effect, resulting in significantly less alcohol consumption. This effect did not occur for freshmen who did not mind such an affiliation. Social others thus can serve as powerful facilitators for, or inhibitors to, consumers’ health and medical decisions.

Choosers versus Consumers

When medical decisions are made by others, social forces affect both the “consumers” of the decision (e.g., the patients) and the “choosers” (e.g., the guardians). The award-winning article by Botti et al. (2009) studied this unique decision dynamic through both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Their focus was on highly consequential and undesirable decisions: parents deciding to discontinue their infants’ life support.

By leveraging a subset of interviews drawn from a large comparative ethnographic study on parents’ experiences in newborn intensive care units, these authors tapped into invaluable insights revealed by parents in two countries—the United States and France—whose babies died after the physicians offered the option to interrupt the life-sustaining treatment and who either autonomously made this tragic decision (American parents) or witnessed the physicians deciding on their behalf (French parents).

The authors found that having autonomy to make tragic choices negatively affected American parents’ psychological pain and grief. While guilt was never mentioned or even indirectly expressed in French parents’ narrative, it was commonly mentioned by American parents. Follow-up lab studies further verified that perceived causality was the driving mechanism: even when most choosers made the “right” decision and reported higher confidence than non-choosers, they felt worse for having made the difficult decision. This research points to the importance of understanding complex medical decision chains in which choosers are not always the consumers of the chosen solution. While the effectiveness of the decision can be lifechanging for the consumers, the process through which these decisions are made can also affect the choosers.

A critical aspect of health and medical decision-making is that this decision process often begins with a health concern/problem, or an anticipation of one. Consumers—driven by self and social factors—seek a solution to address this health concern. The solution can involve (1) human providers such as physicians, (2) non-human providers made available by new technologies such as AI-powered medical assistants, and (3) solution products such as treatment plans and medication. When it comes to human and non-human providers, an interaction between the provider and the patient occurs and a relationship can be developed over time ( Szasz and Hollender 1956 ). Furthermore, providers can express their expertise in various ways, and patients can decide to trust, cooperate, comply, or search for solutions elsewhere. As for the third category of solution products, consumers can hold different beliefs and perceptions about how the products are developed (natural vs. synthetic; Scott, Rozin, and Small 2020 ), how the products actually work (e.g., holistic treatment vs. cause–effect focused, slow vs. fast; Wang et al. 2010 ), and how the products compare with the other options (typical vs. atypical products; Huang and Sengupta 2020 ). Below, we discuss three articles that examined human providers, non-human providers, and product solutions accordingly.

Human Providers

Friedman and Churchill (1987) examined patient–physician relationships from the lens of social power. The authors asked participants to listen to a tape-recorded conversation between a physician and a patient. These recordings featured various medical situations and physicians’ power behaviors and were created based on content analyses of 25 videotaped and 50 transcribed, audiotaped conversations of naturally occurring patient–physician interactions.

The authors found that power behaviors affected patients’ satisfaction and outcomes, but the nature of these influences was rather complex. High (vs. low) expert-legitimate power behaviors led to greater satisfaction and more positive consequences when the medical situation was risky, but these variables were less important in a non-risky situation. High expert-legitimate power behavior also produced greater satisfaction and more positive consequences when the patient and physician had an ongoing relationship but not for new or one-time relationships. Social power behaviors from physicians thus can be effective depending on how serious the patient’s condition is and the nature of the patient–physician relationship.

These results suggest that when a patient interacts with a human provider, the provider’s behaviors and traits (e.g., expertise and power) and the patient’s expectation play important roles in determining whether the patient trusts and follows the provider’s recommendations and the patient’s ultimate health outcome. As it turns out, the patient’s expectation is also a critical driver when the provider is not a human.

Non-Human Providers

With the rapid growth of new technologies and the wide adoption of these technologies in health care, consumers’ receptiveness to medical innovations has emerged as one of the most critical challenges for solution providers to overcome. Through a series of studies, the authors of one of our focal articles ( Longoni et al. 2019 ) demonstrated when consumers are less willing to utilize AI-powered health care, have lower reservation price for it, and derive negative utility from these automated providers.

In one study, the authors informed participants that the analysis of their data could be carried out either by a doctor (human provider) or by a computer (non-human provider) and specified that the two providers had the same accuracy rate of 89%. They further emphasized that there would be no interaction with the provider performing the analysis and that the medical diagnosis would entail the same information and would be delivered according to the same timeline. They found that the participants were willing to pay on average $13.78 USD less to use the non-human provider.

Leveraging the proposed mechanism of “uniqueness neglect,” in another study, the authors manipulated the salience of the provider’s ability to personalize and tailor the analyses and recommendations for the patient (“…the analysis was personalized and tailored to your unique characteristics”). They found that personalized recommendations successfully alleviated consumers’ reluctance to follow the recommendation from the non-human provider. Developing non-human providers that can account for consumers’ unique characteristics and circumstances is thus important in increasing the solutions’ adoption. As medical resources continue to be overtaxed and the need for more efficient, technology-driven providers continues to rise, more research is needed to examine how society can scale up healthcare providers without dampening consumers’ perceptions of the providers’ accuracy and effectiveness, as well as their willingness to follow the recommended actions. We discuss these opportunities further in the Future Directions section.

Solution Products

While medical solutions often involve a certified provider (e.g., meeting with a doctor for diagnosis and prescription), these solutions may eventually be executed through consumers’ purchasing a service (e.g., an fMRI scan) or a product (e.g., a medication). The third category of solutions thus centers on products that consumers purchase to address a health or medical concern. An exemplary article in this category is by Scott et al. (2020) .

These authors showed that natural products—products that do not involve prior human intervention and additives—are preferred when used to prevent a problem than when used to cure a problem. In one study, the authors used publicly available data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to explore 9,972 consumers’ reported use of complementary and alternative medicines over the past year. They found that consumers were more likely to prefer natural remedies when using a treatment as a preventative than as a curative.

This preference occurs because consumers believe that natural products are safer and less potent. When seeking prevention (vs. cure) products, consumers care more about safety and thus are more likely to choose a natural product. Leveraging this underlying mechanism, the authors were able to directly reverse this lay belief by framing the natural drug as stronger and having more side effects (more risk), and the synthetic drug as weaker and having fewer side effects (less risk). This framing successfully reversed the pattern, such that consumers preferred the natural drug when choosing a curative.

While solution drivers are essential in shaping consumers’ health and medical decisions, an effective solution cannot be fully understood or judiciously adopted by consumers without effective marketing communication. Accordingly, health messaging and marketing strategies are used ubiquitously by practitioners and organizations to promote healthy behaviors (see Bou-Karroum et al. 2017 for a review). For example, the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control advocates a number of marketing-based recommendations to discourage smoking, whether in terms of promoting the use of plain (standardized) packaging, displaying enlarged graphic health warnings on cigarette packages, or curbing point-of-sale product displays.

In this section, we take a marketing perspective and highlight some articles that have illuminated how the core elements of the marketing mix can influence consumers’ health and medical decisions, including one of our focal articles ( Bolton et al. 2008 ). Findings from these articles not only enable consumers to better understand the antecedents of their decisions but also inform practitioners in both public and private sectors on how they can strategize to improve the physical and psychological wellbeing of target consumers/constituents.

Health Marketing

Marketers and policymakers use a variety of messages and communication strategies to promote health and medical products, services, and practices. Prior research has shown that the degree to which a health message is persuasive depends on how the message is designed and framed, as well as its interaction with consumers’ dispositional tendencies and situational states ( Aaker and Lee 2001 ; Chandran and Menon 2004 ; Keller 2006 ; Menon, Block, and Ramanathan 2002 ).

Following this line of enquiry, Han et al. (2016) demonstrated that the construal level at which a health message is presented interacts with consumers’ coping strategies to affect the message’s effectiveness. For example, in one study, undergraduates at a US university indicated more favorable attitudes toward a government-run educational program designed to promote healthy physical activities when the ad for the program was framed at a high-level construal (i.e., “Why Do You Engage in Physical Activities in This Program”) among participants induced to think about the positive benefits of emotion-focused coping, but when the ad was framed at a low-level construal (i.e., “How Do You Engage in Physical Activities in This Program”) among participants induced to think about the positive benefits of problem-focused coping.

The authors demonstrated in another study that this matching effect was accompanied by actual reduction of stress in terms of cortisol level. The authors further show that different mechanisms underlie this effect for the two groups of consumers, such that response efficacy mediates the effect of a match between emotion-focused coping and the high-construal level of the health message on persuasion, whereas self-efficacy mediates the effect of a match between problem-focused coping and the low-construal level of the health message on persuasion.

Product Marketing

In medical marketing, even well-intentioned product positioning can backfire, as demonstrated by Bolton et al. (2008) . In this research, how a product is positioned and marketed—either as a drug or a health supplement—led to widely different downstream behaviors by changing how consumers think about their health risks and ability to combat these risks. Surprisingly, they found that marketing a product as a drug (rather than a supplement) makes consumers less likely to engage in healthy lifestyle practices.

The researchers posit that this boomerang effect is attributable to two reasons. First, drugs may reduce consumers’ risk perceptions and hence their perceived importance of and motivation to engage in complementary health-protective behaviors, such as eating low-cholesterol foods. Second, drugs may be associated with poor health that reduces self-efficacy to engage in healthy behaviors. By unpacking these potential mechanisms, the authors suggest (and demonstrate empirically) the potential of using a combined intervention—designed to increase health motivation and health ability—to assuage the adverse boomerang effect of drug marketing.

Pricing is another way that marketers can impact consumers’ health and medical decisions. The price of a drug can even affect consumers’ beliefs about its efficacy ( Waber et al. 2008 ) and thus can lead to a placebo effect ( Shiv, Carmon, and Ariely 2005 ).

Samper and Schwartz (2013) offered a unique perspective of the effects of pricing, showing that the price of a medical product can affect how consumers perceive risk, and in turn, how much of the product to consume. They distinguished between sacred and secular products; medical drugs are generally regarded as lifesaving and are hence sacred products—consider a skin ointment that has a lifesaving function (e.g., prevents skin cancer) instead of one that has a cosmetic benefit (e.g., prevents age spots). Lower prices in sacred, lifesaving products signal these products’ greater accessibility to anyone in need, thereby making consumers think they are more at risk, and in turn, increasing consumers’ intention to consume the products. Conversely, higher prices reduce risk assessment and thus consumption.

Since the abovementioned consumption reduction (due to higher prices and lower risk perception) could apply to both necessary and unnecessary care, it may lead to negative effects on consumer welfare if consumers under-consume the drugs that they ought to. Therefore, to the extent that price serves as a simple proxy for risk and that proxy is inaccurate, appropriate “consumer education about communal need and objective risk” (p. 1354) should accompany price transparency to better inform consumption.

While the highlighted articles above shed light on some ways in which the core elements of the marketing mix, particularly marketing messaging and pricing, can affect consumers’ health and medical decisions, other elements may also play an influential role. For instance, it is conceivable that how a product/service is distributed (e.g., intensively, selectively, or exclusively), where it is sold (e.g., online vs. brick-and-mortar store vs. hybrid/omnichannel), and how it is packaged (e.g., where the picture of a product is located on the packaging; Deng and Kahn 2009 ) can also affect consumers’ judgments and decisions.

Furthermore, turning from these direct influences to more indirect/incidental influences, a longstanding debate in our society is how much mass-media advertising and entertainment have led to adverse effects on health (e.g., through advertising of unhealthy foods, movies depicting smoking, drug use, and alcohol consumption—often through product placement), with moralists and capitalists often standing on opposite sides. Using a compelling natural experiment and NHIS data in the United States, Thomas (2019) demonstrated that television had considerable impact on inducing smoking. His analysis revealed that, between 1946 and 1980, television increased the share of smokers in the population by a striking 5–15%, generating roughly 11 million smokers in the United States. This effect was more influential than price fluctuations and was especially dominant among teens. Juxtaposed against an earlier finding from Connell et al. (2014) where childhood advertising can create biased product evaluations that persist into adulthood, Thomas’ finding is at once alarming and sobering.

Beyond internal factors of the self and external influences of social, solution, and service-provider drivers, consumers’ broader societal and situational environment can also affect their health and medical decisions in systematic ways. As Ross and Nisbett (2011) reminded us in their seminal volume “The Person and the Situation,” the context in which consumers find themselves often interact with their dispositions to influence how they think and behave. Here, we consider work on this driver, including our focal article ( Briley et al. 2017 ).

Consumers’ cultural background may not only shape their self-view ( Markus and Kitayama 1991 ) but also affect how they think and process external information. Centering on the question of how consumers confront health challenges in life, Briley et al. (2017) convincingly demonstrated that cultural background plays a pivotal role in cultivating optimism in difficult times. In particular, the authors distinguish between two mental frames that people can adopt in the face of health challenges: an initiator frame (“how will I act, regardless of the situation I encounter”) and a respondent frame (“how will I react to the situations I encounter”). While optimism is essential in helping people cope with health challenges and recover successfully, the authors propose that people with an independent cultural background are more optimistic about their recovery when adopting an initiator (vs. a responder) frame, whereas people with an interdependent cultural background are more optimistic when adopting a responder (vs. initiator) frame, demonstrating these effects for a variety of health challenges (cancer, diabetes, serious injury from a car accident) and health outcomes (e.g., feeling more optimistic and energetic, willingness to take on more challenging physical therapy, sticking to a doctor-recommended diet).

In one study (study 6), undergraduate students were asked to consider having to confront various health threats after experiencing torrential rains and severe flooding where they lived (e.g., communicable diseases spread by contaminated water). They were then exposed to a public health message about a fictitious vaccine, Immunasil, with either initiator language (“Act now to protect yourself—get vaccinated”) or responder language (“Respond now to protect yourself—get vaccinated”). The authors found that participants with a greater independent self-view were more likely to get vaccinated if they were exposed to the initiator-framed health message, while those with a greater interdependent self-view were more likely to get vaccinated if they were exposed to the responder-framed health message; these results were mediated by the ease with which participants imagined getting vaccinated and their optimism toward the vaccine. These findings provide valuable guidance to firms and public health communicators in their design of health products and messages, reminding practitioners of the importance of considering target consumers’ cultural background in fostering greater optimism and improved wellbeing.

Evolutionary Forces

At a more fundamental level, consumers’ incidental exposure to myriad cues in their environment can activate evolutionarily adapted survival instincts and drive their cognition and behavior. Disease cues are an example of such situational triggers (e.g., Galoni, Carpenter, and Rao 2020 ). These cues have been especially prevalent in the last few years as the world wrestles with multiple variants of the COVID-19 virus and consumers are exposed to widespread daily media coverage of the protracted pandemic.

Huang and Sengupta (2020) show how disease cues may activate consumers’ behavioral immune system and cause them to prefer atypical consumer products (e.g., pomegranate juice) and shy away from more typical products (e.g., orange juice), arguing that disease salience triggers the instinctual, unconscious motivation to avoid social others and, consequently, generate aversion to typical products as such products are associated with many (vs. few) people. Accordingly, this effect was attenuated when the disease with which the cues were associated was noncontagious (e.g., cancer), when anti-disease interventions were also made salient (e.g., handwashing), and when the use of the focal product was less likely to carry the risk of infection (e.g., a set of plates used for decoration rather than as dinnerware).

Huang and Sengupta’s (2020) findings suggest that amid the ongoing pandemic, researchers and practitioners could leverage these insights to boost adoption of certain health-related products (e.g., oat milk) and practices (e.g., fitness programs) by highlighting the atypicality and exclusivity of such offerings. Connecting these findings with the earlier discussion on consumers’ lay beliefs ( Wang et al. 2010 ), Western medicine may be perceived as more (or less) typical than traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine depending on consumers’ cultural background. In this vein, an extrapolation of Huang and Sengupta’s (2020) findings may suggest that exposure to disease cues would lead consumers to prefer the type of medicine that they deem more atypical. Furthermore, they observed the hypothesized evolutionary-adaptation effects by activating less immediately threatening disease cues, which were quite different from the highly salient COVID-19 disease cue. Prolonged social isolation arising from the pandemic may instead lead consumers to desire greater social connectedness, and accordingly, prefer more typical products.

Together, these two articles reveal how deep-seated societal (cultural) and situational (evolutionary) drivers could impact consumers’ health and medical decision-making. They add to a growing body of work that has highlighted the critical roles that these drivers play (e.g., how cultural factors affect the effectiveness of health communication with regard to the source, message, and channel of the communication; Kreuter and McClure 2004 ).

The 5S framework offers rich opportunities and fruitful directions for future research on consumer health and medical decision-making. Below, we highlight four major directions. The former two directions call for research that dives deeper into the complexity of consumer health phenomena, to enhance our understanding of how multiple drivers interact, reinforce, or cancel each other, and how a variety of methodologies and unique samples can be leveraged to shed light on complex yet critical nuances involving different decision types.

The latter two directions call for research that goes bigger —beyond the scope of typical consumer health research—challenging consumer researchers to think more broadly about how improving health and medical decisions can (ironically) be a double-edged sword, potentially leading to undesirable consequences on consumers’ wellbeing and the society. In addition, we encourage researchers to examine how health care can be effectively scaled up to address the prevailing challenges in limited supply and to serve the broader and diverse population. Future research along these lines will generate invaluable insights to ensure positive long-term gain on the health of all consumers.

Going Deeper: Cross-Driver Interactions

To truly understand how consumers make health and medical decisions, the five drivers in the 5S framework cannot be studied in isolation. Indeed, many influential articles we have discussed so far explored cross-driver interactions of two key drivers, such as the effect of a service-provider driver (e.g., product marketing) on a self-driver (e.g., health motivation and health ability, Bolton et al. 2008 ) and the effect of a novel solution driver (e.g., AI provider) on a self -driver (e.g., need for uniqueness, Longoni et al. 2019 ). Potential interactions between two self -drivers have also been of considerable interest to consumer researchers, such as studying how lay beliefs and motivational orientations affect consumers’ perceptions of self-efficacy and response efficacy ( Keller 2006 ; Wang et al. 2010 ).

Beyond Two Drivers

In essence, consumer health is an inherently complex topic that often goes beyond two drivers. For instance, the solution driver of an AI provider can interact with social drivers of assimilation and contrast to inform consumers’ perceptions about themselves: seeing a specific group of consumers (e.g., millennials) rely on technology-mediated treatment platforms may turn away consumers of other age groups (e.g., contrast), especially for consumers whose health abilities or self-efficacy beliefs are low. To truly understand and predict the adoption of AI providers, researchers thus need to consider not only the solution drivers of interest but also relevant self and social drivers simultaneously.

It is also important to recognize that one focal construct can affect two drivers at the same time. For instance, power can be both a societal/situational driver (e.g., some societies have a larger power distance) and a solution driver (e.g., the power conveyed by the physicians, Friedman and Churchill 1987 ); power can even be a service-provider driver (e.g., conveying expertise and power through a marketing message or through price). Hence, to examine how power affects consumers’ medical decisions, researchers may need to consider the interaction between the power in consumers’ environment and the power conveyed by the provider, and how these two types of power jointly affect consumers’ expectations, perceived abilities, and motivation ( Moorman and Matulich 1993 ).

There are also significant opportunities for researchers to dive further into the complexity of societal/situational drivers. As modern consumers place greater emphasis on corporates’ social responsibility efforts, companies and medical institutions are becoming more eager to connect their marketing messages with consumers’ values, such as ensuring equal pay of medical staff, increasing energy efficiency, and reducing medical waste (e.g., the Top 25 Environmental Excellence Awards were recently established to recognize healthcare organizations’ environmental achievements). Societal/situational drivers hence interact heavily with consumers’ self-drivers to inform how service providers should communicate and market their healthcare offerings in the 21st century.

Beyond Two Stakeholders

While researchers should consider the complexity of medical decisions that go beyond two drivers, it is similarly important to consider health decisions that involve more than two stakeholders. For instance, as the population ages, greater insights are needed to understand how consumers select care providers for their aging parents, and how these care providers make day-to-day decisions for the wellbeing of these aging clients. The juxtaposition across these stakeholders underscores the complexity of medical decision-making for aging consumers: while one stakeholder is the ultimate recipient of the service, the second stakeholder makes decisions driven by their social relationship (e.g., duty and love), whereas the third stakeholder—driven mostly by a contractual relationship—may have the most intimate knowledge about the patient’s health conditions and changing mental state. A fourth stakeholder may include distant agencies (e.g., policymakers and payment organizations) who impact treatment through accessibility, legislation, and funding. Future research is needed to ask bold questions and explore complex dimensions involving multiple stakeholders and across multiple drivers.

Going Deeper: Complex Decision Types

Decision type considerations.

Health and medical decisions differ widely along various dimensions ( table 1 ). Depending on the specific attributes of the focal decision, different decision processes (e.g., maximizing vs. satisficing, analytical vs. heuristic based vs. feeling based, compensatory vs. non-compensatory) and psychological mechanisms may operate. While most research focuses on specific decision types, extending the focal decision to other (and more complex) decision types along one or more dimensions may prove advantageous in illuminating the unique psychology driving these decisions. In addition, from a practical and substantive perspective, such an approach will help to inspire new research questions (focusing on new decision contexts/types) and novel ideas to address the health or medical issue at hand.

DIMENSIONS OF COMPLEX DECISION TYPES

For example, prior research has shown that high-stake decisions and those that carry a more persistent impact generally entail a more deliberative and analytical decision process than lower-stake and one-time, short-lived decisions. Would the perceived importance of health as a domain (compared to, say, finance) attenuate these differences, such that more categories of drivers (in the 5S framework) are considered by consumers and exert greater impact even for low-stake medical decisions? While persistent (vs. temporary) health issues may lead to habitual decision-making, given the importance of health as a domain, would the longer duration of impact actually prompt consumers to be more deliberative when choosing? Conversely, might the inherent complexity of these decisions result in consumers’ relying more on arguably less-relevant social and incidental situational drivers?

Another example is health lifecycle. Would the weight consumers put on these drivers change as decisions advance from one health-lifecycle stage (e.g., screening) to another (e.g., maintenance)? What about products that could serve both a preventive/maintenance role and a cure/treatment role ( Scott et al. 2020 ), as in some forms of Asian medication (e.g., cordyceps), depending on the dosage amount? How would consumers perceive such dual-purpose products, and how would these perceptions affect their downstream decisions or behaviors?

Furthermore, what if these health and medical decisions were made jointly (e.g., by two partners in a romantic relationship, or by members of a family)? Would this result in a polarizing effect or an averaging effect on consumers’ risk perceptions? And would this social dynamic depend on the heterogeneity of the decision-making unit ( Yaniv 2011 )? A thoughtful consideration of these rich decision dimensions will help consumer researchers deepen their inquiries, enhancing the generalizability of their theories and establishing meaningful boundaries for their proposed effects.

Methodological Considerations

Depending on the nature and complexity of the health decision that researchers intend to study, a diverse set of methodologies and participant samples may be necessary to lend greater relevance as well as confidence to the findings. Accordingly, prior research has employed a variety of methodologies, from lab and field experiments ( Berger and Rand 2008 ; Bolton et al. 2008 ; Cadario and Chandon 2020 ; Haws et al. 2022 ) to qualitative interviews and participatory-action research ( Botti et al. 2009 ; Tian et al. 2014 ), and from natural experiments and econometric modeling ( Thomas 2019 ) to ethnographic methods ( Hirschman 1992 ; Thompson and Troester 2002 ). Besides providing triangulation and ensuring greater robustness in the empirical results, these varied methods may be necessary to inject diverse perspectives that help illuminate the complexity of the decision or issue of interest.

Furthermore, rather than deductive or inductive methods, an abductive approach ( Janiszewski and van Osselaer 2022 ) can prove beneficial for the discovery of novel theories arising from more complex health and medical decisions. This empirical approach prioritizes system validity ( Reiss 2019 ) over internal or external validity, “encourages broad boundary-expanding exploration,” and possesses “the potential to propose original theories that encompass a large set of relationships” ( Janiszewski and van Osselaer 2022 , 175). Advanced quantitative techniques such as systems modeling and simulation, and the use of genetic algorithms may also be useful in capturing the complexity and evolving nature of these multi-faceted and multiply determined relationships.

Going Bigger: Broader and Opposing Consequences

While the two previous research directions relate to deepening our understanding of the core drivers of health and medical decisions, particularly for decisions that possess vastly different attributes along the five dimensions, the next two research directions call for broadening the scope of research on health and medical decisions, and improving understanding of the implications of this expansion.

Although much of the research on consumer health has focused on specific, unilateral consumer decisions and outcomes, some of these decisions and outcomes may have other downstream consequences for consumers, specific communities, or the society at large. These outcomes can have opposing valence or be even unrelated to health, presenting a tradeoff (or double-edged sword) that necessitates the consideration of multiple perspectives and diverse criteria in evaluating the overall impact. (Notably, the five drivers can serve either as enablers/catalysts or detractors/impediments to positive health and medical decision-making.)

Beyond Price and Risk Perception

For instance, consider the findings of Samper and Schwartz (2013) discussed above. While setting a high price for drugs and medicine may discourage consumption through lowering risk perception, this pricing strategy can also help prevent abuse of the drug and over-consumption (as in the case of antibiotics, whose liberal use may result in adverse health consequences in the long run by making everyone less resistant to new bacterial variants or superbugs). To what extent should public health policymakers simply rely on market forces to drive prices down in response to reduced demand? More broadly, might these authors’ findings help to foster greater education efforts and public awareness of health and preventive actions, leading to additional positive spill-over effects?

Beyond Technology and Mass Production

As another example, consider the burgeoning use of AI, synthetic drugs, and other technological innovations that standardize the quality of health care and mass produce these solutions [see Wood and Schulman (2019) on the importance of understanding how patients respond to five types of disruptive healthcare innovations]. While such advances may render healthcare services more efficient and potentially more affordable and accessible, might they also generate consumer overconfidence, resulting in a boomerang or risk compensation effect ( Peltzman 1975 ), such that consumers perceive a false sense of security and take more risks than otherwise warranted (e.g., being more delinquent in adhering to a prescribed medication regime)? From a systemic standpoint, might the increasing use of non-human technology-mediated solutions in health care enhance efficiency and accuracy at the expense of reduced human warmth, empathy, and trust—qualities that may be especially vital for certain medical decisions (e.g., decisions related to terminal illness, psychotherapy) and for some vulnerable groups of patients (e.g., the elderly, people with disabilities)?

Key Questions

In approaching this research direction, it will be worthwhile to consider several pertinent questions. First, to what extent might consumers’ actions and decisions affect other stakeholders (other than consumers themselves), whether these stakeholders belong to the immediate medical ecosystem or beyond, and whether in terms of health-related or health-unrelated outcomes? Second, what criteria should we use to assess the overall welfare impact of consumers’ decisions (the normative or prescriptive view), either at the consumer level or the broader societal and global level? Third, extending beyond the domain of health care, which other domains are most intimately linked to health and medical decisions (e.g., financial decisions, corporate responsibility, environmental sustainability such as food safety and food security) that key stakeholders and policymakers should consider in concert, either to achieve greater effectiveness (to allow for a more holistic evaluation) or efficiency (to conserve scarce resources)?

Going Bigger: Scaling Up Health Care

We live in a world of limited resources. The limitation lies in human resource, natural resource, software and hardware, money and time. The limitations in health care are startling. Many people cannot access health care because of its cost and their income, others cannot access health care because of geographical constraints, and yet others cannot access health care because they are uninsured. In fact, an estimated 9.6% of US residents (i.e., 31.1 million people) lacked health insurance when surveyed in early 2021 by the CDC. To improve consumers’ health and medical outcomes, we need effective solutions driven by behavioral science to scale up healthcare resources: to (1) increase supply, (2) redefine quality, and (3) broaden the reach.

Increase Supply

To increase the “supply” in health care, we need advanced medical research to discover effective procedures, treatments, and medicines, as well as dedicated policy support to ensure sufficient funding and efficient deployment of resources. Equally important, we also need to recruit behavioral science to help overcome erroneous perceptions and beliefs as well as psychological hurdles in implementation.

Take medical innovation as an example. One way to scale up human providers is to deploy non-human providers more broadly. Instead of seeing a physician for every minor health concern, an AI doctor can leverage data to provide quick diagnoses and issue prescriptions at scale. However, prior research has shown that consumers are hesitant to trust non-human service providers ( Longoni et al. 2019 ; Wood and Schulman 2019 ). In addition, even doctors prefer to rely on their own intuition rather than computerized models ( Keeffe et al. 2005 ). What makes matters worse is that doctors who rely on computerized aids may be evaluated as less competent by others ( Palmeira and Spassova 2015 ; Shaffer et al. 2013 ). To scale up automated service providers, therefore, we not only require better technologies but also a much deeper understanding of human psychologies that are holding us back. One such solution is tested in study 9 in Longoni et al. (2019) . The authors tested a theory-driven task allocation between human and non-human providers—having the non-human provider serve the supporting role and not the substitute effectively alleviated consumers’ reservation about AI providers. We encourage future research to explore more innovative and practical ideas and interventions that can help to scale up healthcare accessibility, leading to broader adoption across different segments of consumers and different domains of service providers, so that more patients can benefit from these medical advancements.

Redefine Quality

Scaling up health care also means bringing better-quality care to more consumers. What constitutes “better-quality care,” however, is debatable. Wang et al. (2010) showed that while Western medicine is known for tackling a specific cause effectively and fixing a focal issue quickly, Eastern medicine is known for its holistic approach, which often takes more time for patients to see improvement. Our society has put great emphasis on efficiency and has little patience for solutions that are slow or when progress is less observable; yet slower but more holistic approach may actually help to strengthen consumers’ overall health, leading to long-term improvements and thus reducing future need for medical treatments. In this light, research that helps consumers and service providers re-envision what constitutes better-quality care will go a long way toward solving the demand-versus-supply issue in health care.

Similarly, holistic care, by definition, aims to address patients' physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs, restore their balance, and enable them to deal with their illnesses, consequently improving their quality of life ( Tjale and Bruce 2007 ). This means that service providers and solution drivers should think carefully about the delicate balance between prolonging one’s life and ensuring one’s wellbeing or general life quality. A shortsighted focus on prolonging life alone not only taxes the healthcare system but can also induce substantial harm to the patient and the patient’s social circle. But unless consumers are made aware of these broader and longer-term costs, they will likely continue to rely on service providers’ recommendations and feel compelled to exhaust all solutions. Research on these psychological obstacles and experiments on smart interventions are needed to increase consumers’ awareness, trust, and knowledge about these intricate and difficult tradeoffs.

Broaden Reach

Finally, scaling up health care means broadening the reach of health and medical resources, especially for vulnerable consumer segments and underserved communities. For instance, Du et al. (2008) studied how a corporate oral health initiative can be beneficial (on both societal and business terms) to disadvantaged Hispanic families by strengthening these children’s beliefs about the physical and psychosocial benefits of oral health behaviors. Research on the health and medical needs of specific ethnic groups is desperately needed to increase adoption and ensure fairness as we scale up healthcare resource.

Another example is the aging consumer. Based on a report by the World Health Organization, by 2030, one in six people in the world will be aged 60 years or over. The number of persons aged 80 years or older is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050 to reach 426 million, and 80% of older people will be living in low- and middle-income countries. The aging population introduces a unique challenge to health care, as recent research has shown that objective and subjective age are often orthogonal ( Amatulli et al. 2018 ; Park et al. 2021 ): whereas geriatric physicians often describe their elderly patients with stereotypical traits associated with old age (e.g., tired and frail), their patients tend to describe themselves instead with traits reflecting young age (e.g., energetic and lively; Kastenbaum et al. 1972 ). Such patient–physician discrepancies can affect the quality of care for the elderly, the patients’ willingness to accept care, and their ultimate health outcomes and life expectancy ( Markides and Pappas 1982 ). More generally, elderly consumers have different health and medical needs than younger adults; on a morbid yet critical note, healthcare systems may have over-emphasized prolonging lives instead of also helping individuals prepare for their exit ( Gawande 2014 ). Accordingly, it would be imperative for consumer researchers to employ behavioral science to better understand the needs and wants of elderly consumers and to help them achieve healthier longevity and lead more fulfilling lives.

Just like many behavioral science domains, research on health and medical decision-making has long suffered from the WEIRD phenomenon, in which the majority of social science studies have focused on participants who are Western, educated, and from industrialized, rich, and democratic countries ( Arnett 2008 ; Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan 2010 ; Rad, Martingano, and Ginges 2018 ). To meaningfully broaden the reach of health care, our mission as behavioral scientists is to broaden our research—to identify unique psychological barriers as well as unique opportunities to improve health and medical decisions among the consumer segments that are traditionally less studied. Failure in understanding these unique psychologies will prevent an effective scale-up of our medical resources; success in capturing these unique psychologies and decision-making processes, on the other hand, will benefit our society as a whole. The challenge is huge, and we believe that consumer researchers play a critical role in leading this change.

Szu-chi Huang ( [email protected] ) is an associate professor of marketing and an R. Michael Shanahan Faculty Scholar at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, 655 Knight Way, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Leonard Lee ( [email protected] ) is a professor of marketing at NUS Business School and Deputy Director at Lloyd's Register Foundation Institute for the Public Understanding of Risk, National University of Singapore (NUS), 15 Kent Ridge Drive, 119245, Singapore. Please address correspondence to Szu-chi Huang.

The authors thank Carolyn Lo and Jason Zhou for their research assistance on this work. The authors also thank the editors, especially Stacy Wood, for the invaluable feedback and comments.

This curation was invited by editors Bernd Schmitt, June Cotte, Markus Giesler, Andrew Stephen, and Stacy Wood.

Aaker Jennifer L. , Lee Angela Y. ( 2001 ), “ I’ Seek Pleasures and ‘We’ Avoid Pains: The Role of Self-Regulatory Goals in Information Processing and Persuasion ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 28 ( 1 ), 33 – 49 .

Google Scholar

Amatulli Cesare , Peluso Alessandro M. , Guido Gianluigi , Yoon Carolyn ( 2018 ), “ When Feeling Younger Depends on Others: The Effects of Social Cues on Older Consumers ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 45 ( 4 ), 691 – 709 .

Arnett Jeffrey J. ( 2008 ), “ The Neglected 95%: Why American Psychology Needs to Become Less American ,” The American Psychologist , 63 ( 7 ), 602 – 14 .

Aubree Shay L. , Lafata Jennifer Elston ( 2015 ), “ Where Is the Evidence? A Systematic Review of Shared Decision Making and Patient Outcomes ,” Medical Decision Making , 35 ( 1 ), 114 – 31 .

Bandura Albert ( 1982 ), “ Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency ,” American Psychologist , 37 ( 2 ), 122 – 47 .

Berger Jonah , Rand Lindsay ( 2008 ), “ Shifting Signals to Help Health: Using Identity Signaling to Reduce Risky Health Behaviors ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 35 ( 3 ), 509 – 18 .

Bolton Lisa E. , Cohen Joel B. , Bloom Paul N. ( 2006 ), “ Does Marketing Products as Remedies Create ‘Get out of Jail Free Cards’? ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 33 ( 1 ), 71 – 81 .

Bolton Lisa E. , Reed Americus , Volpp Kevin G. , Armstrong Katrina ( 2008 ), “ How Does Drug and Supplement Marketing Affect a Healthy Lifestyle? ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 34 ( 5 ), 713 – 26 .

Botti Simona , Orfali Kristina , Iyengar Sheena S. ( 2009 ), “ Tragic Choices: Autonomy and Emotional Responses to Medical Decisions ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 36 ( 3 ), 337 – 52 .

Bou-Karroum Lama , El-Jardali Fadi , Hemadi Nour , Faraj Yasmine , Ojha Utkarsh , Shahrour Maher , Darzi Andrea , Ali Maha , Doumit Carine , Langlois Etienne V. , Melki Jad , AbouHaidar Gladys Honein , Akl Elie A. ( 2017 ), “ Using Media to Impact Health Policy-Making: An Integrative Systematic Review ,” Implementation Science , 12 ( 1 ), 52 .

Briley Donnel A. , Rudd Melanie , Aaker Jennifer ( 2017 ), “ Cultivating Optimism: How to Frame Your Future during a Health Challenge ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 44 ( 4 ), 895 – 915 .

Cadario Romain , Chandon Pierre ( 2020 ), “ Which Healthy Eating Nudges Work Best? A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments ,” Marketing Science , 39 ( 3 ), 465 – 86 .

Chandran Sucharita , Menon Geeta ( 2004 ), “ When a Day Means More than a Year: Effects of Temporal Framing on Judgments of Health Risk ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 31 ( 2 ), 375 – 89 .

Chung Jaeyeon (Jae) , Lee Leonard ( 2019 ), “ To Buy or to Resist: When Upward Social Comparison Discourages New Product Adoption ,” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research , 4 ( 3 ), 280 – 92 .

Connell Paul M. , Brucks Merrie , Nielsen Jesper H. ( 2014 ), “ How Childhood Advertising Exposure Can Create Biased Product Evaluations That Persist into Adulthood ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 41 ( 1 ), 119 – 34 .

Deng Xiaoyan , Kahn Barbara E. ( 2009 ), “ Is Your Product on the Right Side? The ‘Location Effect’ on Perceived Product Heaviness and Package Evaluation ,” Journal of Marketing Research , 46 ( 6 ), 725 – 38 .

Du Shuili , Sen Sankar , Bhattacharya C. B. ( 2008 ), “ Exploring the Social and Business Returns of a Corporate Oral Health Initiative Aimed at Disadvantaged Hispanic Families ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 35 ( 3 ), 483 – 94 .

Dzhogleva Hristina , Lamberton Cait Poynor ( 2014 ), “ Should Birds of a Feather Flock Together? Understanding Self-Control Decisions in Dyads ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 41 ( 2 ), 361 – 80 .

Festinger Leon ( 1954 ), “ A Theory of Social Comparison Processes ,” Human Relations , 7 ( 2 ), 117 – 40 .

Fishbach Ayelet , Tu Yanping ( 2016 ), “ Pursuing Goals with Others ,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass , 10 ( 5 ), 298 – 312 .

Fitzsimons Gráinne M. , Finkel Eli J. ( 2010 ), “ Interpersonal Influences on Self-Regulation ,” Current Directions in Psychological Science , 19 ( 2 ), 101 – 5 .

Friedman Margaret L. , Churchill Gilbert A. Jr. ( 1987 ), “ Using Consumer Perceptions and a Contingency Approach to Improve Health Care Delivery ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 13 ( 4 ), 492 .

Galoni Chelsea , , Gregory S. Carpenter , and , Hayagreeva Rao ( 2020 ), “ Disgusted and Afraid: Consumer Choices under the Threat of Contagious Disease ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 47 ( 3 ), 373 – 92 .

Gawande Atul ( 2014 ), Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End , New York : Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company.

Google Preview

Han Dahee , Duhachek Adam , Agrawal Nidhi ( 2016 ), “ Coping and Construal Level Matching Drives Health Message Effectiveness via Response Efficacy or Self-Efficacy Enhancement ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 43 ( 3 ), 429 – 47 .

Haws Kelly L. , Liu Peggy J. , McFerran Brent , Chandon Pierre ( 2022 ), “ Examining Eating: Bridging the Gap between ‘Lab Eating’ and ‘Free-Living Eating’ ,” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research , 7 ( 4 ), 403 – 18 .

Haws Kelly L. , Reczek Rebecca Walker , Sample Kevin L. ( 2017 ), “ Healthy Diets Make Empty Wallets: The Healthy 5 Expensive Intuition ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 43 ( 6 ), ucw078 .

Henrich Joseph , Heine Steven J. , Norenzayan Ara ( 2010 ), “ The Weirdest People in the World? ,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences , 33 ( 2-3 ), 61 – 83 .

Hirschman Elizabeth C. ( 1992 ), “ The Consciousness of Addiction: Toward a General Theory of Compulsive Consumption ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 19 ( 2 ), 155 – 79 .

Huang Yunhui , Sengupta Jaideep ( 2020 ), “ The Influence of Disease Cues on Preference for Typical versus Atypical Products ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 47 ( 3 ), 393 – 411 .

Huang Szu-Chi , Broniarczyk Susan M. , Zhang Ying , Beruchashvili Mariam ( 2015 ), “ From Close to Distant: The Dynamics of Interpersonal Relationships in Shared Goal Pursuit ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 41 ( 5 ), 1252 – 66 .

Janiszewski Chris , van Osselaer Stijn M. J. ( 2022 ), “ Abductive Theory Construction ,” Journal of Consumer Psychology , 32 ( 1 ), 175 – 93 .

Kastenbaum Robert , Derbin Valerie , Sabatini Paul , Artt Steven ( 1972 ), “ The Ages of Me’: Toward Personal and Interpersonal Definitions of Functional Aging ,” Aging and Human Development , 3 ( 2 ), 197 – 211 .

Keeffe Brian , Subramanian Usha , Tierney William M. , Udris Edmunds , Willems Jim , McDonell Mary , Fihn Stephan D. ( 2005 ), “ Provider Response to Computer-Based Care Suggestions for Chronic Heart Failure ,” Medical Care , 43 ( 5 ), 461 – 5 .

Keller Punam A. ( 2006 ), “ Regulatory Focus and Efficacy of Health Messages ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 33 ( 1 ), 109 – 14 .

Kreuter Matthew W. , McClure Stephanie M. ( 2004 ), “ The Role of Culture in Health Communication ,” Annual Review of Public Health , 25 , 439 – 55 .

Kulik James A. , Mahler Heike I. M. ( 2000 ), “Social Comparison, Affiliation, and Emotional Contagion under Threat,” in Handbook of Social Comparison , ed. Jerry Suls and Ladd Wheeler, Boston, MA : Springer , 295 – 320 .

Liu Peggy , Dallas Steven K. , Fitzsimons Gavan J. ( 2019 ), “ A Framework for Understanding Consumer Choices for Others ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 46 ( 3 ), 407 – 34 .

Longoni Chiara , Bonezzi Andrea , Morewedge Carey K. ( 2019 ), “ Resistance to Medical Artificial Intelligence ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 46 ( 4 ), 629 – 50 .

Markides Kyriakos S. , Pappas Charisse ( 1982 ), “ Subjective Age, Health, and Survivorship in Old Age ,” Research on Aging , 4 ( 1 ), 87 – 96 .

Markus Hazel R. , Kitayama Shinobu ( 1991 ), “ Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation ,” Psychological Review , 98 ( 2 ), 224 – 53 .

McFerran Brent , Dahl Darren W. , Fitzsimons Gavan J. , Morales Andrea C. ( 2010 ), “ I’ll Have What She’s Having: Effects of Social Influence and Body Type on the Food Choices of Others ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 36 ( 6 ), 915 – 29 .

Menon Geeta , Block Lauren G. , Ramanathan Suresh ( 2002 ), “ We’re at as Much Risk as We Are Led to Believe: Effects of Message Cues on Judgments of Health Risk ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 28 ( 4 ), 533 – 49 .

Moorman Christine , Matulich Erika ( 1993 ), “ A Model of Consumers’ Preventive Health Behaviors: The Role of Health Motivation and Health Ability ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 20 ( 2 ), 208 – 28 .

Palmeira Mauricio , Spassova Gerri ( 2015 ), “ Consumer Reactions to Professionals Who Use Decision Aids ,” European Journal of Marketing , 49 ( 3/4 ), 302 – 26 .

Park Jen H , Huang Szu‐chi , Rozenkrants Bella , Kupor Daniella ( 2021 ), “ Subjective Age and the Greater Good ,” Journal of Consumer Psychology , 31 ( 3 ), 429 – 49 .

Peltzman Sam ( 1975 ), “ The Effects of Automobile Safety Regulation ,” Journal of Political Economy , 83 ( 4 ), 677 – 725 .

Rad Mostafa Salari , Martingano Alison Jane , Ginges Jeremy ( 2018 ), “ Toward a Psychology of Homo Sapiens: Making Psychological Science More Representative of the Human Population ,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 115 ( 45 ), 11401 – 5 .

Raghunathan Rajagopal , Naylor Rebecca Walker , Hoyer Wayne D. ( 2006 ), “ The Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition and Its Effects on Taste Inferences, Enjoyment, and Choice of Food Products ,” Journal of Marketing , 70 ( 4 ), 170 – 84 .

Reiss Julian ( 2019 ), “ Against External Validity ,” Synthese , 196 ( 8 ), 3103 – 21 .

Ross Lee , Nisbett Richard E. ( 2011 ), The Person and the Situation: Perspectives of Social Psychology , London, UK : Pinter & Martin Publishers.

Samper Adriana , Schwartz Janet A. ( 2013 ), “ Price Inferences for Sacred versus Secular Goods: Changing the Price of Medicine Influences Perceived Health Risk ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 39 ( 6 ), 1343 – 58 .

Scott Sydney E. , Rozin Paul , Small Deborah A. ( 2020 ), “ Consumers Prefer ‘Natural’ More for Preventatives than for Curatives ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 47 ( 3 ), 454 – 71 .

Shaffer Victoria A. , Probst C. Adam , Merkle Edgar C. , Arkes Hal R. , Medow Mitchell A. ( 2013 ), “ Why Do Patients Derogate Physicians Who Use a Computer-Based Diagnostic Support System? ,” Medical Decision Making , 33 ( 1 ), 108 – 18 .

Shiv Baba , Carmon Ziv , Ariely Dan ( 2005 ), “ Placebo Effects of Marketing Actions: Consumers May Get What They Pay For ,” Journal of Marketing Research , 42 ( 4 ), 383 – 93 .

Strull William M. , Lo Bernard , Charles Gerald ( 1984 ), “ Do Patients Want to Participate in Medical Decision Making? ,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association , 252 ( 21 ), 2990 – 4 .

Szasz Thomas S. , Hollender Marc H. ( 1956 ), “ A Contribution to the Philosophy of Medicine: The Basic Models of the Doctor-Patient Relationship ,” A.M.A. Archives of Internal Medicine , 97 ( 5 ), 585 – 92 .

Tesser Abraham ( 1988 ), “ Toward a Self-Evaluation Maintenance Model of Social Behavior ,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology , 21 ( C ), 181 – 227 .

Thomas Michael ( 2019 ), “ Was Television Responsible for a New Generation of Smokers? ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 46 ( 4 ), 689 – 707 .

Thompson Craig J. , Troester Maura ( 2002 ), “ Consumer Value Systems in the Age of Postmodern Fragmentation: The Case of the Natural Health Microculture ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 28 ( 4 ), 550 – 71 .