MINI REVIEW article

Sexual orientation and gender identity: review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems.

- Instituto Universitário de Lisboa ISCTE-IUL, CIS, Lisboa, Portugal

Numerous controversies and debates have taken place throughout the history of psychopathology (and its main classification systems) with regards to sexual orientation and gender identity. These are still reflected on present reformulations of gender dysphoria in both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and the International Classification of Diseases, and in more or less subtle micro-aggressions experienced by lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans patients in mental health care. The present paper critically reviews this history and current controversies. It reveals that this deeply complex field contributes (i) to the reflection on the very concept of mental illness; (ii) to the focus on subjective distress and person-centered experience of psychopathology; and (iii) to the recognition of stigma and discrimination as significant intervening variables. Finally, it argues that sexual orientation and gender identity have been viewed, in the history of the field of psychopathology, between two poles: gender transgression and gender variance/fluidity.

Numerous controversies and debates have taken place throughout the history of psychopathology and mental health care with regards to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. The present paper aims to review relevant concepts in this literature, its historical and current controversies, and their relation to the main psychopathology classification systems.

Concepts and Definitions

Concepts and definitions that refer to sexual orientation and gender identity are an evolving field. Many of the terms used in the past to describe LGBT people, namely in the mental health field, are now considered to be outdated and even offensive.

Sexual orientation refers to the sex of those to whom one is sexually and romantically attracted ( American Psychological Association, 2012 ). Nowadays, the terms ‘lesbian’ and ‘gay’ are used to refer to people who experience attraction to members of the same sex, and the term ‘bisexual’ describe people who experience attraction to members of both sexes. It should be noted that, although these categories continue to be widely used, sexual orientation does not always appear in such definable categories and, instead, occurs on a continuum ( American Psychological Association, 2012 ), and people perceived or described by others as LGB may identify in various ways ( D’Augelli, 1994 ).

The expression gender identity was coined in the middle 1960s, describing one’s persistent inner sense of belonging to either the male and female gender category ( Money, 1994 ). The concept of gender identity evolved over time to include those people who do not identify either as female or male: a “person’s self concept of their gender (regardless of their biological sex) is called their gender identity” ( Lev, 2004 , p. 397). The American Psychological Association (2009a , p. 28) described it as: “the person’s basic sense of being male, female, or of indeterminate sex.” For decades, the term ‘transsexual’ was restricted for individuals who had undergone medical procedures, including genital reassignment surgeries. However, nowadays, ‘transsexual’ refers to anyone who has a gender identity that is incongruent with the sex assigned at birth and therefore is currently, or is working toward, living as a member of the sex other than the one they were assigned at birth, regardless of what medical procedures they may have undergone or may desire in the future (e.g., Serano, 2007 ; American Psychological Association, 2009a ; Coleman et al., 2012 ). In this paper we use the prefix trans when referring to transsexual people.

Since the 1990’s the word transgender has been used primarily as an umbrella term to describe those people who defy societal expectations and assumptions regarding gender (e.g., Lev, 2004 ; American Psychological Association, 2009a ). It includes people who are transsexual and intersex, but also those who identify outside the female/male binary and those whose gender expression and behavior differs from social expectations. As in the case of sexual orientation, people perceived or described by others as transgender – including transsexual men and women – may identify in various ways (e.g., Pinto and Moleiro, 2015 ).

Discrimination and Impact on Mental Health

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people often suffer from various forms of discrimination, stigma and social exclusion – including physical and psychological abuse, bullying, persecution, or economic alienation ( United Nations, 2011 ; Bostwick et al., 2014 ; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014 ). Moreover, experiences of discrimination may occur in various areas, such as employment, education and health care, but also in the context of meaningful interpersonal relationships, including family (e.g., Milburn et al., 2006 ; Feinstein et al., 2014 ; António and Moleiro, 2015 ). Accordingly, several studies strongly suggest that experiences of discrimination and stigmatization place LGBT people at higher risk for mental distress ( Cochran and Mays, 2000 ; Dean et al., 2000 ; Cochran et al., 2003 ; Meyer, 2003 ; Shilo, 2014 ).

For example, LGB populations may be at increased risk for suicide ( Hershberger and D’Augelli, 1995 ; Mustanski and Liu, 2013 ), traumatic stress reactions ( D’Augelli et al., 2002 ), major depression disorders ( Cochran and Mays, 2000 ), generalized anxiety disorders ( Bostwick et al., 2010 ), or substance abuse ( King et al., 2008 ). In addition, transgender people have been identified as being at a greater risk for developing: anxiety disorders ( Hepp et al., 2005 ; Mustanski et al., 2010 ); depression ( Nuttbrock et al., 2010 ; Nemoto et al., 2011 ); social phobia and adjustment disorders ( Gómez-Gil et al., 2009 ); substance abuse ( Lawrence, 2008 ); or eating disorders ( Vocks et al., 2009 ). At the same time, data on suicide ideation and attempts among this population are alarming: Maguen and Shipherd (2010) found the percentage of attempted suicides to be as high as 40% in transsexual men and 20% in transsexual women. Nuttbrock et al. (2010) , using a sample of 500 transgender women, found that around 30% had already attempted suicide, around 35% had planned to do so, and close to half of the participants expressed suicide ideation. In particular, adolescence has been identified as a period of increased risk with regard to the mental health of transgender and transsexual people ( Dean et al., 2000 ).

In sum, research clearly recognizes the role of stigma and discrimination as significant intervening variables in psychopathology among LGBT populations. Nevertheless, the relation between sexual orientation or gender identity and stress may be mediated by several variables, including social and family support, low internalized homophobia, expectations of acceptance vs. rejection, contact with other LGBT people, or religiosity ( Meyer, 2003 ; Shilo and Savaya, 2012 ; António and Moleiro, 2015 ; Snapp et al., 2015 ). Thus, it seems important to focus on subjective distress and in a person-centered experience of psychopathology.

On the History of Homosexuality and Psychiatric Diagnoses

While nowadays we understand that higher rates of psychological distress among LGB people are related to their minority status and to discrimination, by the early 20th century, psychiatrists mostly regarded homosexuality as pathological per se ; and in the mid-20th century psychiatrics, physicians, and psychologists were trying to “cure” and change homosexuality ( Drescher, 2009 ). In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association published its first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-I), in which homosexuality was considered a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” In DSM-II, published in 1968, homosexuality was reclassified as a “sexual deviation.” However, in December 1973, the American Psychiatric Association’s Board of Trustees voted to remove homosexuality from the DSM.

The most significant catalyst to homosexuality’s declassification as a mental illness was lesbian and gay activism, and its advocacy efforts within the American Psychiatric Association ( Drescher, 2009 ). Nevertheless, during the discussion that led to the diagnostic change, APA’s Nomenclature Committee also wrestled with the question of what constitutes a mental disorder. Concluding that “they [mental disorders] all regularly caused subjective distress or were associated with generalized impairment in social effectiveness of functioning” ( Spitzer, 1981 , p. 211), the Committee agreed that homosexuality by itself was not one.

However, the diagnostic change did not immediately end the formal pathologization of some presentations of homosexuality. After the removal of the “homosexuality” diagnosis, the DSM-II contained the diagnosis of “sexual orientation disturbance,” which was replaced by “ego dystonic homosexuality” in the DSM-III, by 1980. These diagnoses served the purpose of legitimizing the practice of sexual “conversion” therapies among those individuals with same-sex attractions who were distressed and reported they wished to change their sexual orientation ( Spitzer, 1981 ; Drescher, 2009 ). Nonetheless, “ego-dystonic homosexuality” was removed from the DSM-III-R in 1987 after several criticisms: as formulated by Drescher (2009 , p. 435): “should people of color unhappy about their race be considered mentally ill?”

The removal from the DSM of psychiatric diagnoses related to sexual orientation led to changes in the broader cultural beliefs about homosexuality and culminated in the contemporary civil rights quest for equality ( Drescher, 2012 ). In contrast, it was only in 1992 that the World Health Organization ( World Health Organization, 1992 ) removed “homosexuality” from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), which still contains a diagnosis similar to “ego-dystonic homosexuality.” However, this is expected to change in the next revision, planned for publication in 2017 ( Cochran et al., 2014 ).

Controversies on Gender Dysphoria and (Trans)Gender Diagnoses

Mental health diagnoses that are specific to transgender and transsexual people have been highly controversial. In this domain, the work of Harry Benjamin was fundamental for trans issues internationally, through the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (presently, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, WPATH). In the past few years, there has been a vehement discussion among interested professionals, trans and LGBT activists, and human rights groups concerning the reform or removal of (trans)gender diagnoses from the main health diagnostic tools. However, discourses on this topic have been inconclusive, filled with mixed messages and polarized opinions ( Kamens, 2011 ). Overall, mental health diagnoses which are specific to transgender people have been criticized in large part because they enhance the stigma in a population which is already particularly stigmatized ( Drescher, 2013 ). In fact, it has been suggested that the label “mental disorder” is the main factor underlying prejudice toward trans people ( Winter et al., 2009 ).

The discussion reached a high point during the recent revision process of the DSM-5 ( American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ), in which the diagnosis of “gender identity disorder” was revised into one of “gender dysphoria.” Psychiatric diagnosis was thus limited to those who are, in a certain moment of their lives, distressed about living with a gender assignment they experience as incongruent with their gender identity ( Drescher, 2013 ). The change of criteria and nomenclature “is less pathologizing as it no longer implies that one’s identity is disordered” ( DeCuypere et al., 2010 , p. 119). In fact, gender dysphoria is not a synonym for transsexuality, nor should it be used to describe transgender people in general ( Lev, 2004 ); rather, “[it] is a clinical term used to describe the symptoms of excessive pain, agitation, restless, and malaise that gender-variant people seeking therapy often express” ( Lev, 2004 , p. 910). Although the changes were welcomed (e.g., DeCuypere et al., 2010 ; Lev, 2013 ), there are still voices arguing for the “ultimate removal” ( Lev, 2013 , p. 295) of gender dysphoria from the DSM. Nevertheless, attention is presently turned to the ongoing revision of the ICD. Various proposals concerning the revision of (trans)gender diagnoses within ICD have been made, both originating from transgender and human rights groups (e.g., Global Action for Trans ∗ Equality, 2011 ; TGEU, 2013 ) and the health profession community (e.g., Drescher et al., 2012 ; World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2013 ). These include two main changes: the reform of the diagnosis of transsexualism into one of “gender incongruence”; and the change of the diagnosis into a separate chapter from the one on “mental and behavioral disorders.”

Mental Health Care Reflecting Controversies

There is evidence that LGBT persons resort to psychotherapy at higher rates than the non-LGBT population ( Bieschke et al., 2000 ; King et al., 2007 ); hence, they may be exposed to higher risk for harmful or ineffective therapies, not only as a vulnerable group, but also as frequent users.

Recently, there has been a greater concern in the mental health field oriented to the promotion of the well-being among non-heterosexual and transgender people, which has paralleled the diagnostic changes. This is established, for instance, by the amount of literature on gay and lesbian affirmative psychotherapy which has been developed in recent decades (e.g., Davis, 1997 ) and, also, by the fact that major international accrediting bodies in counseling and psychotherapy have identified the need for clinicians to be able to work effectively with minority clients, namely LGBT people. The APA’s guidelines for psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual client ( American Psychological Association, 2000 , 2012 ) are a main reference. These ethical guidelines highlight, among several issues, the need for clinicians to recognize that their own attitudes and knowledge about the experiences of sexual minorities are relevant to the therapeutic process with these clients and that, therefore, mental health care providers must look for appropriate literature, training, and supervision.

However, empirical research also reveals that some therapists still pursue less appropriate clinical practices with LGBT clients. In a review of empirical research on the provision of counseling and psychotherapy to LGB clients, Bieschke et al. (2006) encountered an unexpected recent explosion of literature focused on “conversion therapy.” There are, in fact, some mental health professionals that still attempt to help lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients to become heterosexual ( Bartlett et al., 2009 ), despite the fact that a recent systematic review of the peer-reviewed journal literature on sexual orientation change efforts concluded that “efforts to change sexual orientation are unlikely to be successful and involve some risk of harm” ( American Psychological Association, 2009b , p. 1).

Moreover, there is evidence of other forms of inappropriate (while less blatant) clinical practices with LGBT clients (e.g., Garnets et al., 1991 ; Jordan and Deluty, 1995 ; Liddle, 1996 ; Hayes and Erkis, 2000 ). Even those clinicians who intend to be affirmative and supportive of LGBT individuals can reveal subtle heterosexist bias in the work with these clients ( Pachankis and Goldfried, 2004 ). Examples of such micro-aggressions ( Sue, 2010 ) might be automatically assuming that a client is heterosexual, trying to explain the etiology of the client’s homosexuality, or focusing on the sexual orientation of a LGB client despite the fact that this is not an issue at hand (e.g., Shelton and Delgado-Romero, 2011 ). Heterosexual bias in counseling and psychotherapy may manifest itself also in what Brown (2006 , p. 350) calls “sexual orientation blindness,” i.e., struggling for a supposed neutrality and dismissing the specificities related to the minority condition of non-heterosexual clients. This conceptualization of the human experience mostly in heterosexual terms, found in the therapeutic setting, does not seem to be independent of psychotherapist’s basic training and the historical heterosexist in the teaching of medicine and psychology ( Simoni, 1996 ; Alderson, 2004 ).

With regards to the intervention with trans people, for decades the mental health professionals’ job was to sort out the “true” transsexuals from all other transgender people. The former would have access to physical transition, and the later would be denied any medical intervention other than psychotherapy. By doing this, whether deliberately or not, professionals – acting as gatekeepers – pursued to ‘ensure that most people who did transition would not be “gender-ambiguous” in any way’ ( Serano, 2007 , p. 120). Research shows that currently trans people still face serious challenges in accessing health care, including those related to inappropriate gatekeeping ( Bockting et al., 2004 ; Bauer et al., 2009 ). Some mental health professionals still focus on the assessment of attributes related to identity and gender expressions, rather than on the distress with which trans people may struggle with ( Lev, 2004 ; Serano, 2007 ). Hence, trans people may feel the need to express a personal narrative consistent with what they believe the clinicians’ expectations to be, for accessing hormonal or surgical treatments ( Pinto and Moleiro, 2015 ). Thus, despite the revisions of (trans)gender diagnoses within the DSM, more recent diagnoses seem to still be used as if they were identical with the diagnosis of transsexualism – in a search for the “true transsexual” ( Cohen-Kettenis and Pfäfflin, 2010 ). It seems clear that social and cultural biases have significantly influenced – and still do – diagnostic criteria and the access to hormonal and surgical treatments for trans people.

Controversies and debates with regards to medical classification of sexual orientation and gender identity contribute to the reflection on the very concept of mental illness. The agreement that mental disorders cause subjective distress or are associated with impairment in social functioning was essential for the removal of “homosexuality” from the DSM in the 1970s ( Spitzer, 1981 ). Moreover, (trans)gender diagnoses constitute a significant dividing line both within trans related activism (e.g., Vance et al., 2010 ) and the health professionals’ communities (e.g., Ehrbar, 2010 ). The discussion has taken place between two apposite positions: (1) trans(gender) diagnoses should be removed from health classifying systems, because they promote the pathologization and stigmatization of gender diversity and enhance the medical control of trans people’s identities and lives; and (2) trans(gender) diagnoses should be retained in order to ensure access to care, since health care systems rely on diagnoses to justify medical treatment – which many trans people need. In fact, trans people often describe experiences of severe distress and argue for the need for treatments and access to medical care ( Pinto and Moleiro, 2015 ), but at the same time reject the label of mental illness for themselves ( Global Action for Trans ∗ Equality, 2011 ; TGEU, 2013 ). Thus, it may be important to understand how the debate around (trans)diagnoses may be driven also by a history of undue gatekeeping and by stigma involving mental illness.

The present paper argues that sexual orientation and gender identity have been viewed, in the history of the field of psychopathology, between two poles: gender transgression and gender variance/fluidity.

On the one hand, aligned with a position of “transgression” and/or “deviation from a norm,” people who today are described as LGBT were labeled as mentally ill. Inevitably, classification systems reflect(ed) the existing social attitudes and prejudices, as well as the historical and cultural contexts in which they were developed ( Drescher, 2012 ; Kirschner, 2013 ). In that, they often failed to differentiate between mental illness and socially non-conforming behavior or fluidity of gender expressions. This position and the historical roots of this discourse are still reflected in the practices of some clinicians, ranging from “conversion” therapies to micro-aggressions in the daily lives of LGBT people, including those experienced in the care by mental health professionals.

On the other hand, lined up with a position of gender variance and fluidity, changes in the diagnostic systems in the last few decades reflect a broader respect and value of the diversity of human sexuality and of gender expressions. This position recognizes that the discourse and practices coming from the (mental) health field may lead to changes in the broader cultural beliefs ( Drescher, 2012 ). As such, it also recognizes the power of medical classifications, health discourses and clinical practices in translating the responsibility of fighting discrimination and promoting LGBT people’s well-being.

In conclusion, it seems crucial to emphasize the role of specific training and supervision in the development of clinical competence in the work with sexual minorities. Several authors (e.g., Pachankis and Goldfried, 2004 ) have argued for the importance of continuous education and training of practitioners in individual and cultural diversity competences, across professional development. This is in line with APA’s ethical guidelines ( American Psychological Association, 2000 , 2012 ), and it is even more relevant when we acknowledge the significant and recent changes in this field. Furthermore, it is founded on the very notion that LGBT competence assumes clinicians ought to be aware of their own personal values, attitudes and beliefs regarding human sexuality and gender diversity in order to provide appropriate care. These ethical concerns, however, have not been translated into training programs in medicine and psychology in a systematic manner in most European countries, and to the mainstreaming of LGBT issues ( Goldfried, 2001 ) in psychopathology.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alderson, K. G. (2004). A different kind of outing: training counsellors to work with sexual minority clients. Can. J. Couns. 38, 193–210.

Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th Edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychological Association (2000). Guidelines for psychotherapy with lesbian, Gay Bisexual Clients. Am. Psychol. 55, 1440–1451.

American Psychological Association (2009a). Report of the Task Force on Gender Identity and Gender Variance. Available at: http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/policy/gender-identity-report.pdf

American Psychological Association (2009b). Report of the American Psychological Association Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/therapeutic-response.pdf

American Psychological Association (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Am. Psychol. 67, 10–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024659

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

António, R., and Moleiro, C. (2015). Social and parental support as moderators of the effects of homophobic bullying on psychological distress in youth. Psychol. Schools 52, 729–742. doi: 10.1002/pits.21856

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bartlett, A., Smith, G., and King, M. (2009). The response of mental health professionals to clients seeking help to change or redirect same-sex sexual orientation. BMC Psychiatry 9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-11

Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., and Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: how erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 20, 348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004

Bieschke, K. J., McClanahan, M., Tozer, E., Grzegorek, J. L., and Park, J. (2000). “Programmatic research on the treatment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients: the past, the present, and the course for the future,” in Handbook of Counseling and Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients , eds R. M. Perez, K. A. DeBord, and K. J. Bieschke (Washington DC: American Psychological Association), 309–335.

Bieschke, K. J., Paul, P. L., and Blasko, K. A. (2006). “Review of empirical research focused on the experience of lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients in counseling and psychotherapy,” in Handbook of Counseling and Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients , eds K. Bieschke, R. Perez, and K. DeBord (Washington DC: American Psychological Association), 293–316.

Bockting, W., Robinson, B., Benner, A., and Scheltema, K. (2004). Patient satisfaction with transgender health services. J. Sex Marital Ther. 30, 277–294. doi: 10.1080/00926230490422467

Bostwick, W. B., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T. L., and McCabe, S. E. (2010). Sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 100, 468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942

Bostwick, W. B., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T. L., West, B. T., and McCabe, S. E. (2014). Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry (Am. Psychol. Assoc.) 84, 35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0098851

Brown, L. S. (2006). “The neglect of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered clients,” in Evidence-Based Practices in Mental Health , eds J. C. Norcross, L. E. Beutler, and R. F. Levant (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 346–353.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Cochran, S., Drescher, J., Kismödi, E., Giami, A., García-Moreno, C., Atalla, E., et al. (2014). Proposed declassification of disease categories related to sexual orientation in the international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-11). Bull. World Health Organ. Bull. 92, 672–679. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.135541

Cochran, S. D., and Mays, V. M. (2000). Relation between psychiatric syndromes and behaviourally defined sexual orientation in a sample of the U.S. population. Am. J. Public Health 92, 516–523.

Cochran, S. D., Sullivan, J. G., and Mays, V. M. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J. Couns. Clin. Psychol. 71, 53–61.

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., and Pfäfflin, F. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 39, 499–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9562-y

Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen - Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., et al. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people, 7th version. Int. J. Transgend. 13, 165–232.

D’Augelli, A. R. (1994). “Identity development and sexual orientation: toward a model of lesbian, gay, and bisexual development,” in Human Diversity: Perspectives on People in Context , eds E. J. Trickett, R. J. Watts, and D. Birman (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

D’Augelli, A. R., Pilkington, N. W., and Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychol. Q. 17, 148–167. doi: 10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854

Davis, D. (1997). “Towards a model of gay affirmative therapy,” in Pink Therapy: A Guide for Counsellors and Therapists Working with Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Clients , eds D. Davies and C. Neal (Buckingham: Oxford University Press), 24–40.

Dean, L., Meyer, I. H., Robinson, K., Sell, R. L., Sember, R., Silenzio, V. M. B., et al. (2000). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: findings and concerns. J. Gay Lesbian Med. Assoc. 4, 102–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1009573800168

DeCuypere, G. D., Knudson, G., and Bockting, W. (2010). Response of the world professional association for transgender health to the proposed dsm 5 criteria for gender incongruence. Int. J. Transgend. 12, 119–123. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2010.509214

Drescher, J. (2009). Queer diagnoses: parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality. Gender Variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Arch. Sex. Behav. 39, 427–460. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9531-5

Drescher, J. (2012). The removal of homosexuality from the dsm: its impact on today’s marriage equality debate. J. Gay Lesbian Mental Health 16, 124–135. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2012.653255

Drescher, J. (2013). Controversies in gender diagnoses. LGBT Health 1, 10–14.

Drescher, J., Cohen-Kettenis, F., and Winter, S. (2012). Minding the body: situating gender identity diagnoses in the ICD-1. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 24, 568–577. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.741575

Ehrbar, R. D. (2010). Consensus from differences: lack of professional consensus on the retention of the gender identity disorder diagnosis. Int. J. Transgend. 12, 60–74. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2010.513928

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014). European LGBT Survey: Main Results. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Feinstein, B. A., Wadsworth, L. P., Davila, J., and Goldfried, M. R. (2014). Do parental acceptance and family support moderate associations between dimensions of minority stress and depressive symptoms among lesbians and gay men? Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 45, 239–246. doi: 10.1037/a0035393

Garnets, L., Hancock, K. A., Cochran, S. D., Goodchilds, J., and Peplau, L. A. (1991). Issues in psychotherapy with lesbians and gay men. A Survey of Psychologists. Am. Psychol. 46, 964–972. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.9.964

Global Action for Trans ∗ Equality (2011). It’s Time for Reform. Trans ∗ Health Issues in the International Classification of Diseases. A Report on the GATE Experts Meeting. Available at: http://globaltransaction.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/its-time-for-reform.pdf

Goldfried, M. R. (2001). Integrating lesbian, gay, and bisexual issues into mainstream psychology. Am. Psychol. 56, 977–988. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.11.977

Gómez-Gil, E., Trilla, A., Salamero, M., Godás, T., and Valdés, M. (2009). Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychiatric characteristics of transsexuals from Spain. Arch. Sex. Behav. 38, 378–392. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9307-8

Hayes, J., and Erkis, A. (2000). Therapist homophobia, client sexual orientation, and source of client HIV infection as predictors of therapist reactions to clients with HIV. J. Couns. Psychol. 47, 71–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.71

Hepp, U., Kraemer, B., Schynder, U., Miller, N., and Delsignore, A. (2005). Psychiatric comorbidity in gender identity disorder. J. Psychosom. Res. 58, 259–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.010

Hershberger, S. L., and D’Augelli, A. R. (1995). The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Dev. Psychol. 31, 65–74. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.65

Jordan, K. M., and Deluty, R. H. (1995). Clinical Interventions by psychologists with lesbians and gay men. J. Clin. Psychol. 51, 448–456.

Kamens, S. R. (2011). On the proposed sexual and gender identity diagnoses for dsm-5: history and controversies. Hum. Psychol. 39, 37–59. doi: 10.1080/08873267.2011.539935

King, M., Semlyen, J., Killaspy, H., Nazareth, I., and Osborn, D. (2007). A Systematic Review of Research on Counselling and Psychotherapy for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender People. London: British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy.

King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., et al. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

Kirschner, S. R. (2013). Diagnosis and its discontents: critical perspectives on psychiatric nosology and the DSM. Fem. Psychol. 23, 10–28. doi: 10.1177/0959353512467963

Lawrence, A. A. (2008). “Gender identity disorders in adults: diagnosis and treatment,” in Handbook of Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders , eds D. L. Rowland and L. Incrocci (New York, NY: Wiley), 423–456.

Lev, A. I. (2004). Transgender Emergence: Therapeutic Guidelines for Working with Gender-Variant People and their Families. New York, NY: Haworth Clinical Practice Press.

Lev, A. I. (2013). Gender dysphoria: two steps forward, one step back. Clin. Soc. Work J. 41, 288–296. doi: 10.1007/s10615-013-0447-0

Liddle, B. J. (1996). Therapist sexual orientation, gender, and counseling practices as they relate to ratings of helpfulness by gay and lesbian clients. J. Couns. Psychol. 43, 394–401. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.43.4.394

Maguen, S., and Shipherd, J. (2010). Suicide risk among transgender individuals. Psychol. Sex. 1, 34–43. doi: 10.1080/19419891003634430

Meyer, I. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual. (issues)and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Milburn, N. G., Ayala, G., Rice, E., Batterham, P., and Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2006). Discrimination and exiting homelessness among homeless adolescents. Cultur. Divers Ethn. Minor Psychol. 12, 658–672. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.658

Money, J. (1994). The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years. J. Sex Marital Ther. 20, 163–177. doi: 10.1080/00926239408403428

Mustanski, B., and Liu, R. T. (2013). A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Arch. Sex. Behav. 42, 437–448. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9

Mustanski, B. S., Garofalo, R., and Emerson, E. M. (2010). Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Res. Pract. 100, 2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319

Nemoto, T., Bodeker, B., and Iwamoto, M. (2011). Social support, exposure to violence, and transphobia: correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. Am. J. Public Health 101, 1980–1988. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285

Nuttbrock, L., Hwahng, S., Bockting, W., Rosenblum, A., Mason, M., Macri, M., et al. (2010). Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. J. Sex Res. 47, 12–23. doi: 10.1080/00224490903062258

Pachankis, J. E., and Goldfried, M. R. (2004). Clinical issues in working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Psychotherapy Theor. Res. Pract. Train. 41, 227–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.3.227

Pinto, N., and Moleiro, C. (2015). Gender trajectories: transsexual people coming to terms with their gender identities. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 46, 12–20. doi: 10.1037/a0036487

Serano, J. (2007). Whipping Girl. A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press.

Shelton, K., and Delgado-Romero, E. A. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: the experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer clients in psychotherapy. J. Couns. Psychol. 58, 210–221. doi: 10.1037/a0022251

Shilo, G. R., and Savaya, R. (2012). Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and young adults: differential effects of age, gender, religiosity, and sexual orientation. J. Res. On Adolesc. 22, 310–325.

Shilo, G. Z. (2014). The Impact of Minority Stressors on the Mental and Physical Health of Lesbian. Gay, and Bisexual Youths and Young Adults. Health Soc. Work 39, 161–171.

Simoni, J. M. (1996). Confronting heterosexism in the teaching of psychology. Teach. Psychol. 23, 220–226. doi: 10.1207/s15328023top2304_3

Snapp, S. D., Watson, R. J., Russell, S. T., Diaz, R. M., and Ryan, C. (2015). Social support networks for lgbt young adults: low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Fam. Relations 64, 420–430. doi: 10.1111/fare.12124

Spitzer, R. L. (1981). The diagnostic status of homosexuality in the DSM-III: a reformulation of the issues. Am. J. Psychiatry 138, 210–215. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.2.210

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley.

TGEU (2013). TGEU’s Position on the Revision of the ICD z10. Available at: http://www.tgeu.org/sites/default/files/TGEU%20Position%20ICD%20Revision_0.pdf

United Nations (2011). Discriminatory Laws and Practices and Acts of Violence Against Individuals Based on their Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Available at: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/19session/A.HRC.19.41_English.pdf

Vance, S., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Drescher, J., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F., Pfäfflin, F., and Zucker, K. J. (2010). Opinions about the dsm gender identity disorder diagnosis: results from an international survey administered to organizations concerned with the welfare of transgender people. Int. J. Transgend. 12, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/15532731003749087

Vocks, S., Stahn, C., Loenser, L., and Tegenbauer, U. (2009). Eating and body image disturbances in male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals. Arch. Sex. Behav. 38, 364–377. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9424-z

Winter, S., Chalungsooth, P., Teh, Y., Rojanalert, N., Maneerat, K., Wong, Y., et al. (2009). Transpeople, transprejudice and pathologization: a seven-country factor analysis study. Int. J. Sex. Health 21, 96–118. doi: 10.1080/19317610902922537

World Health Organization (1992). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th rev.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Professional Association for Transgender Health (2013). WPATH ICD-11 Consensus Meeting. Available at: http://www.wpath.org/uploaded_files/140/files/ICD%20Meeting%20Packet-Report-Final-sm.pdf

Keywords : sexual orientation, gender identity, transgender, discrimination, psychopathology, mental health care

Citation: Moleiro C and Pinto N (2015) Sexual orientation and gender identity: review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Front. Psychol. 6:1511. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01511

Received: 29 July 2015; Accepted: 18 September 2015; Published: 01 October 2015.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2015 Moleiro and Pinto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carla Moleiro, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa ISCTE-IUL, CIS, Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisbon, Portugal, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Analysis Author Guidelines

- Analysis Reviews Author Guidelines

- Submission site

- Why Publish with Analysis?

- About Analysis

- About The Analysis Trust

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. gender identity first, 3. the no connection view, 4. contextualism, 5. pluralism, 6. further and future work.

- < Previous

Recent Work on Gender Identity and Gender

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Rach Cosker-Rowland, Recent Work on Gender Identity and Gender, Analysis , Volume 83, Issue 4, October 2023, Pages 801–820, https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/anad027

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Our gender identity is our sense of ourselves as a woman, a man, as genderqueer or as another gender. Trans people have a gender identity that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth. Some recent work has discussed what it is to have a sense of ourselves as a particular gender, what it is to have a gender identity ( Andler 2017 , Bettcher 2009 , 2017 , Jenkins 2016 , 2018 , McKitrick 2015 ). But beyond the question of how we should understand gender identity is the question of how gender identities relate to genders.

Our gender is the property we have of being a woman, being a man, being non-binary or being another gender. What is the relationship between our gender identity and our gender? According to many people’s conceptions and the standards operative in trans communities, our gender identity always determines our gender. Other people and communities have different views and standards: some hold that our gender is determined by the gender we are socially positioned or classed as, others hold that our gender is determined by whether we have particular biological features, such as the chromosomes we have. If our gender is determined by our gendered social position or whether we have certain biological features, then our gender identity will not determine our gender.

There are several different ways of approaching the question what is the relationship between our gender identity and our gender? We can approach this question as a descriptive or hermeneutical question about our current concepts of gender identity and gender: what is the relationship between our concept of gender identity and our concept of gender? ( Bettcher 2013 , Diaz-Leon 2016 , Laskowski 2020 , McGrath 2021 , Cosker-Rowland forthcoming , Saul 2012 ) Rather than focusing on descriptive questions about our gender concepts, many feminists, such as Sally Haslanger (2000) and Katharine Jenkins (2016) , have proposed ameliorative accounts of the concepts of gender which we should accept; these are gender concepts which they argue that we can use to further the feminist purposes of fights against gender injustice and campaigns for trans rights. We might then ask the ameliorative question, what is the relationship between our gender identity and our gender according to the concepts of gender and gender identity that we should accept? However, some of the most interesting recent work on the relationship between gender identity and gender has focussed on the metaphysical issue of the relationship between being a member of a particular gender kind G (e.g. being a woman) and having gender identity G (e.g. having a female gender identity). As we’ll see, we can answer these different questions in different ways: for instance, we can hold that we should adopt concepts such that someone is a woman iff they have a female gender identity but hold that metaphysically someone is a woman iff they are treated as a woman by their society, that is, iff they are socially positioned as a woman.

Four positions about the relationship between gender identity and gender that give answers to these ameliorative and metaphysical questions have emerged. This article will explain and evaluate these four positions. In order to understand these different views about the relationship between gender identity and gender it will help to have a little understanding of recent work on gender identity. The two most well-known and popular accounts of gender identity in the analytical philosophy literature are the self-identification account and the norm-relevancy account. On the self-identification account, to have a female gender identity is to self-identify as a woman. One way of explaining what it means to self-identify as a woman is to hold that such self-identification consists in a disposition to assert that one is a woman when asked what gender one is. 1 On the norm-relevancy account, to have a female gender identity is to experience the norms associated with women in your social context (e.g. the norm, women should shave their legs) as relevant to you ( Jenkins 2016 , 2018 ).

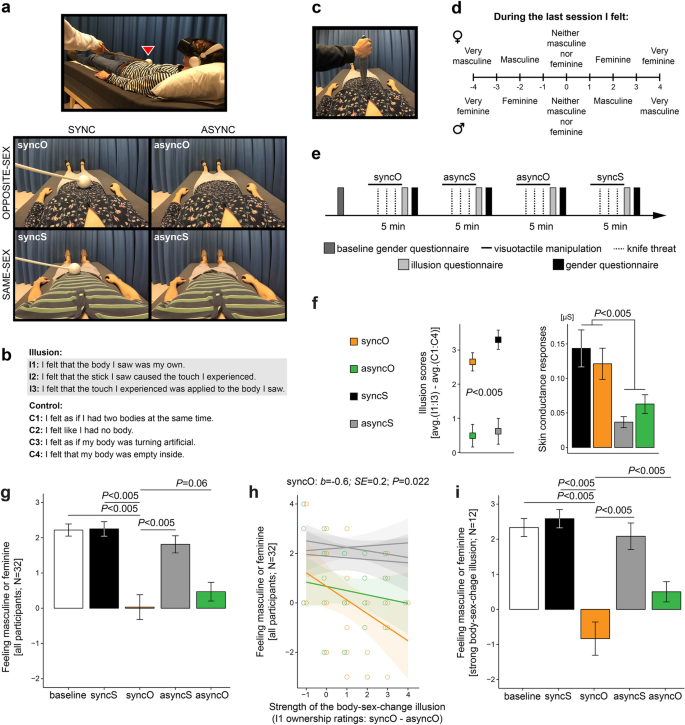

A first view of the relationship between gender and gender identity is what we can call gender identity first . According to a metaphysical version of gender identity first , what it is to be gender G (e.g. a woman) is to have a G gender identity (e.g. to have a female gender identity). Talia Bettcher (2009 : 112), B.R. George and R.A. Briggs (m.s.: §1.3–4), Iskra Fileva (2020 : esp. 193), and Susan Stryker (2006 : 10) argue for gender identity first or views similar to it. And the view that our gender is always determined by our gender identity is, as Briggs and George discuss, part of the standard view in many trans communities and among activists for trans rights. One key virtue of gender identity first is that it ensures that gender is always consensual: on this view, we can be correctly gendered as gender G (e.g. as a woman) only if we identify as a G , and so we can be correctly gendered as a G only if we consent to be gendered as a G by others ( George and Briggs m.s. : §1.3) ( Figure 1 ). 2

Gender identity first

Elizabeth Barnes (2022 : 2) argues that we should reject gender identity first as both a metaphysical and as an ameliorative view. She argues that

(i) Some severely cognitively disabled people do not have gender identities, but

(ii) These severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders and should be categorized as having genders.

And in this case, although having gender identity G is sufficient for being gender G , it is not necessary for being gender G nor necessary for being categorized as a G according to the concepts of gender that we should accept. So, we should reject gender identity first as both a metaphysical view and as an ameliorative view.

Regarding (i), Barnes argues that gender identity

requires awareness of various social norms and roles (and, moreover an awareness of them as gendered), the ability to articulate one’s own relationship to those norms and roles, and so on. But many cognitively disabled people have little or no access to language. Many tend not to understand social norms, much less to identify those norms as specifically gendered. (6)

The norm-relevancy account of gender identity implies that this is true, since on this view having a gender identity involves taking certain gendered social norms to be relevant to you. And the self-identification account also seems to imply that having a gender identity involves having capacities that many severely cognitively disabled people do not have, since self-identification as a particular gender involves a linguistic capacity to say or be disposed to say that one is, or think of oneself as, a particular gender, and many severely cognitively disabled people do not have these capacities.

Barnes has two arguments for

(ii) Severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders.

First, Barnes argues that severely cognitively disabled people who do not have gender identities nonetheless have genders because they suffer gender-based oppression ( 2022 : 11–12). For instance, severely cognitively disabled women are subject to gendered violence and forced sterilization to a greater degree than severely cognitively disabled men. This argument may seem strongest as an argument for (ii) as a metaphysical claim: the view that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders is the best explanation of what we find happening in the world.

Second, Barnes argues that holding that some severely cognitively disabled people do not have genders because they do not have gender identities would involve othering, alienating or dehumanizing these severely cognitively disabled people. Gender identity first implies that agender people do not have genders because their gender identity is that they have no gender. But Barnes argues that gender identity first’s implication that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities lack a gender is more pernicious. Agender people have the capacity to form a gender identity but they opt-out of gender. Gender identity first implies that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities fail to have genders because they do not have the capacity to form a gender identity. So, it implies that they fail to have a gender in the way that tables and animals fail to have a gender – by failing to have the right capacities to have a gender – rather than in the way that agender people do so; for agender people have these capacities. Therefore, Barnes argues, gender identity first others and alienates severely cognitively disabled people from other humans, since all other humans have the capacity to have a gender and having a gender (or opting out of it) is a central part of human (social life). 3 This second argument seems best understood as an argument that we shouldn’t adopt concepts of gender that imply that one is gender G iff one has gender identity G because there are moral and political costs to adopting such concepts.

A second account of the relationship between gender identity and gender is the opposite view; this view understands gender identity and gender as entirely disconnected. On this no connection view, the fact that a woman has a sense of herself as a woman is never what makes her a woman; other features of her, such as the way that she is socially positioned, the way she was socialized, or her biological features, make her a woman.

Several accounts of gender imply the no connection view, including Haslanger’s (2000) influential account of gender. Haslanger’s account was originally proposed as an ameliorative account of the concepts of gender that we should adopt rather than as a metaphysical account of gender properties. But in later work Haslanger also endorsed her account of gender as a metaphysical account of gender properties ( 2012 : e.g. 133–134). On Haslanger’s account, to be a woman is to be systematically subordinated because one is observed or imagined to have bodily features that are presumed to be evidence of a female’s biological role in reproduction; on Haslanger’s view, women are sexually marked subordinates. This view of what it is to be a woman implies that one’s being a woman is never determined by one’s female gender identity. Since, whether one has a sense of oneself as a woman, is disposed to assert that one is a woman or takes norms associated with women to be relevant to one, is neither necessary nor sufficient for one to be a sexually marked subordinate.

Although our gender is not directly determined by our gender identity on Haslanger’s account, one’s female gender identity can indirectly lead one to be a woman on Haslanger’s account. For instance, a trans woman’s female gender identity may lead her to take estradiol which will make her have female sex characteristics, which may lead to her being assumed to play a female biological role in reproduction, to be oppressed accordingly, and so to be a woman on Haslanger’s account. In this case, on Haslanger’s account, someone’s female gender identity can indirectly lead to their becoming a woman ( Figure 2 ).

The n o connection view

Other accounts of gender similarly imply the no connection view of the relationship between gender identity and gender. According to Bach’s (2012) account of gender, to be a woman one has to have been socialized as a woman. But one can have a sense of oneself as a woman without having been socialized as a woman and one can be socialized as a woman without forming a sense of oneself as a woman. So, having a female gender identity is neither necessary nor sufficient to be a woman on Bach’s account (although it may be more likely that A will have a sense of themself as a woman if A was socialized as a woman). Biological or sex-based accounts of gender on which our genders are determined by our biological features, such as our chromosomes, also imply the no connection view, since to have a female gender identity is neither necessary nor sufficient for having XX chromosomes. 4

The no connection view implies that many trans women are not women. For instance, Haslanger’s version of this view implies that trans women who are not presumed to have female sex characteristics by those in their society are not women; so trans women who are not recognised as women, or who ‘do not pass’, 5 are not women. This is because such trans women are not observed or imagined to have features that are presumed to be evidence of a female’s biological role in reproduction. There are many such trans women. So, no connection views such as Haslanger’s imply that many trans women are not women ( Jenkins 2016 : 398–402). Some have argued that this is an unacceptable result for a metaphysical view about the relationship between gender identity and gender, either because all trans women are women or because this view would marginalize trans women within contemporary feminism ( Mikkola 2016 : 100–102). These implications are even more problematic for ameliorative no connection views, that is, for views of how gender identity and gender are related according to the concepts that we ought to accept. For we should not adopt gender concepts that imply that we should not classify many trans women as women ( Jenkins 2016 ).

Furthermore, trans communities and trans-inclusive communities ascribe gender entirely on the basis of the gender identities people express or which people are presumed to have. Another problem with the no connection view is that it may seem to imply that there are no genders being tracked or ascribed in these communities ( Jenkins 2016 : 400–401; Ásta 2018 : 73–74).

These problems do not establish that Haslanger’s account of gender should be abandoned entirely. Elizabeth Barnes (2020) has recently argued that we can rescue Haslanger’s account of gender from the problem that it excludes trans women by understanding it as an account of what explains our experiences of gender. According to Barnes’ version of Haslanger’s account, our practices of gendering people, and our gender identities, are the product of Haslangerian social practices of subordinating and privileging people on the basis of perceived sex characteristics. Barnes’ version of Haslanger’s account does not imply that one is a woman iff one is systematically subordinated because one is observed or imagined to have bodily features that are presumed to be evidence of one’s playing a female’s biological role in reproduction. This is because Barnes’ account is only an account of what gives rise to our experiences of gender rather than an account of who has what gender properties or of the gender concepts that we should accept. Barnes might rescue a version of Haslanger’s account from the problem that it excludes trans women. But if she does, she does this by revising Haslanger’s account so that it drops the no connection view of the relationship between gender identities and gender; Barnes’ revised version of Haslanger’s account of gender is instead silent on the issue of the relationship between having gender identity G and being a member of gender G . So, Barnes’ rescue of Haslanger’s account of gender does not rescue the no connection view of the relationship between gender identity and gender.

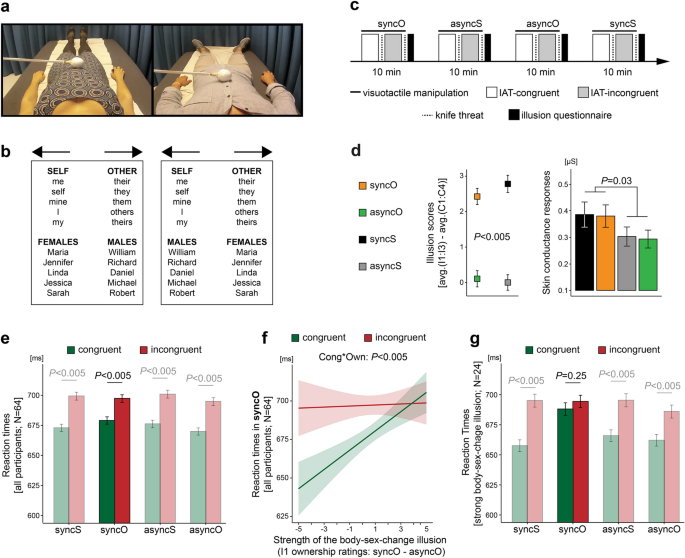

Gender identity first and no connection views such as Haslanger’s are invariantist views of the relationship between gender identity and gender: they hold that the relationship between gender identity and gender does not vary across different contexts. A third account of the relationship between gender identity and gender is the opposite of invariantism, contextualism. According to this view, the features that determine our gender, and so the relationship between gender identity and gender, is different from context to context.

Ásta (2018) and Robin Dembroff (2018) have proposed and/or defended forms of (metaphysical) contextualism. On their views, the gender properties that we have, or the gender kinds that we are members of, are determined by the way that we are treated in particular contexts. We are a member of gender G in virtue of our gender identity G in certain contexts, namely trans-inclusive contexts where people are treated as genders based on their (avowed) gender identities. But in other contexts, we are never a member of gender G in virtue of our gender identity G : in contexts in which people are treated as a gender based on features other than their gender identities – such as traditional or conservative societies – we are not members of genders based on our gender identities. For instance, trans woman Amy is a woman in the context of the support group Trans Leeds – she is a woman (Trans Leeds) – but she is not a women in the context of her conservative parents in Henley who don’t recognize her as a woman and who treat people as women based on the chromosomes that they believe them to have – she is not a woman (family-in-Henley) . And Alex is non-binary in the context of the support group Non-Binary Leeds, where one is conferred a particular gender status based on one’s avowed self-identification – they are non-binary (Non-Binary Leeds) – but Alex is perceived as male in most contexts and is treated as male regardless of their self-identification at school, work and in public, and so Alex is not non-binary in most contexts – e.g. they are not non-binary (Alex’s school) . Importantly, on this view, there is no such thing as being gender G simpliciter , that is, beyond whether one is a G -relative-to-a-certain-context – and the way one is treated or the standards that are operative in that context. So, it is not the case that Alex is non-binary simpliciter or genuinely non-binary; they are merely non-binary relative to one standard or context and not non-binary relative to another.

Contextualism can explain why the way that some people are gendered varies from context to context: in explaining her contextualist view, Ásta (2018 : 73–74) gives an example of a coder who is one of the guys at work, neither a guy nor a girl at the bars they go to after work, and one of the women – and expected to help out like all the other women – at their grandmother’s house (85–86). Contextualism also allows us to explain how sometimes people are gendered on the basis of their perceived biological features and sometimes gendered based on their avowed (or assumed) gender identities. Dembroff argues that a contextualist view is particularly useful in explaining how, in many societies and contexts, trans people are unjustly constrained, or as they put it ‘ontologically oppressed’, by being constructed and categorized as a member of a category with which they do not identify; identifying such ontological oppression is essential to explaining the oppression that trans people face ( Dembroff 2018 : 24–26, Jenkins 2020 ) ( Figure 3 ).

Contextualism

However, there are several problems with contextualism. One problem is that it implies that gender critical feminists are, in a sense, right when they claim that trans women are not women and trans men are not men because trans women are not women according to the standards of many people and of many places: in many places trans women, for instance, are not treated as women, and in many places trans women are not women relative to the dominant standard for who is a woman, which is sex-based or biology-based. So, for instance, when in 2021 the then Tory UK Health Secretary Sajid Javid said that ‘only women have cervixes’, according to contextualism, what he said was true in a sense: only women (dominant UK-standards) have cervixes; and only women (Tory party conference) have cervixes. Even though it is false that only women (Trans Leeds) have cervixes because trans men have cervixes. This conclusion may seem problematic and paralyzing because it implies that Javid’s claim is true in a sense in certain contexts, and we cannot truthfully claim that it is just plain false ( Saul 2012 : 209–210, Diaz-Leon 2016 : 247–248). 6

Ásta (2018 : e.g. 87–88) and Dembroff (2018) argue that we can solve this problem by holding that, although it is true that trans men are not men relative to most dominant UK contexts, we should still treat and classify trans men as men. We should classify trans men as men because facts about how we should classify someone – the gender properties that we should treat them as having – are established by moral and political considerations. But although we should classify trans men as men, they are not – as a matter of social metaphysical fact – men (dominant UK contexts) . So, we should accept contextualism as a metaphysical view about the relationship between gender identity and gender but not as an ameliorative view about the gender concepts we should accept; we can call this combination of views purely metaphysical contextualism.

Dembroff (2018 : 38–48) recognizes that purely metaphysical contextualism may seem to have problematic implications. It may seem to imply that many trans women (for instance) are mistaken when they say that they are women in many contexts, such as dominant UK and US contexts, where there are chromosomes-based or assigned-sex-at-birth-based gender standards. Yet Dembroff argues that purely metaphysical contextualism does not have this problematic implication because trans women are women relative to the gender kinds operative in trans-inclusive contexts.

However, this will not always be a helpful form of correctness. Suppose that Alicia is a trans woman in London in 1840. There are no trans-inclusive societies, communities or contexts that she knows of. But she takes herself to be a woman, and suppose that according to both of the accounts of gender identity that we discussed in §1, Alicia has a female gender identity. We can say that Alicia’s judgement that she is a woman is correct in the sense that it is correct-relative to the gender kinds operative in future contexts and fictional contexts. But any judgment that we might make is true relative to the standards in some future or merely possible context. And we might wonder why it matters that someone’s judgment about their own gender is true relative to the standards operative in some future context that they could not possibly be aware of. This form of truth is not what they want and it’s hard to see why it should be relevant in this context. Furthermore, trans people are widely held to be misguided, mentally unstable, suffering from a delusion or making believe ( Bettcher 2007 , Serano 2016 : ch. 2, Lopez 2018 , Rajunov and Duane 2019 : xxiv). If the only interesting way in which Alicia is correct about her gender is that she is that gender according to standards far in the future that she is not aware of, then it would seem that Alicia is misguided about her gender – given that she could not know about these standards – and that she is in a sense making believe. This seems like an undesirable consequence, especially if we think that Alicia is really a woman, that is, that she is not misguided.

There are two further, more general, problems for contextualism. 7 First, contextualism seems to clash with how many of us think about our own and others’ genders. For instance, many trans men think that they should be classified as men because they are men, and not just because they are men-relative to the standards of trans-inclusive communities and societies ( Saul 2012 : 209–210). 8 Gender critical feminists think that trans women are not women, that standards which align with this view track the standard-independent truth, and standards which don’t align with this view do not.

Second, contextualism seems to be in tension with the idea that many of our disagreements about gender are genuine disagreements. Suppose that contextualism is true and that we (and everyone else) accept it. In this case, it is hard for us to sincerely genuinely disagree with Javid about whether only women have cervixes. Since, when he says that only women have cervixes we know that he means that only those who count as women, relative to the dominant UK standards or relative to the standards operative amongst Tory MPs and members, have cervixes. And we agree with him about this, since we know that according to these standards trans men are women. So, if contextualism is true and we accept it, it is hard for us to genuinely disagree with Javid. Contextualism could be true without our knowing or believing it. In this case, we could genuinely disagree with Javid. But our disagreement here would only be possible because we are significantly mistaken about what kinds of things gender kinds are; we think gender kinds are not all context- or standard-relative but in fact they are. And attributing such a significant mistake to all of us is a significant cost of a metaphysical theory, for other things equal we should accept more charitable theories that do not imply that we are significantly mistaken rather than theories that do imply this ( Olson 2011 : 73–77, McGrath 2021 : 35, 46–48).

These problems with contextualism about the relationship between gender identity and gender are analogues of problems that contextualist views face in other domains such as in metaethics. According to metaethical contextualism, moral claims, their meanings and their truth are always standard-relative. There is no such thing as an act being morally wrong, only its being morally-wrong-relative-to-utilitarianism or morally-wrong-relative-to-the-standards-of-Victorian-England. But metaethical contextualism faces a problem explaining fundamental moral disagreement. Act-utilitarians and Kantians agree that pushing the heavy man off of the bridge in the footbridge trolley case is wrong (Kantianism) and right (act-utilitarianism) but they still disagree and they take themselves to be disagreeing about which of their moral standards is correct, and which standard tracks the truth about which actions are right and wrong simpliciter ( Olson 2011 : 73–77, Cosker-Rowland 2022 : 57–59). If there are no non-context- or standard-relative properties of right and wrong, then although Kantians and Utilitarians do disagree – they think there are such properties – there is in fact nothing for them to disagree about. So, metaethical contextualism seems to be committed to a kind of error theory about morality that, other things equal, we should avoid: Kantians and Utilitarians think that they are talking about which of their moral standards is independently correct, but there is no such standard-independent moral correctness. Contextualists in metaethics have developed several types of resources to mitigate this kind of problem or to enable contextualism to explain what’s happening in these disagreements better. Perhaps these proposals could be used to mitigate the analogous problems with contextualism about the relationship between gender identity and gender. McGrath (2021 : esp. 42–49) considers this possibility and argues that these responses are not plausible, and that they face similar problems to the problems faced by the analogous responses proposed by contextualists in metaethics. 9 More broadly, whether contextualists’ proposals to mitigate these problems for metaethical contextualism do, or could, succeed is contested ( Cosker-Rowland 2022 : 59–64). 10

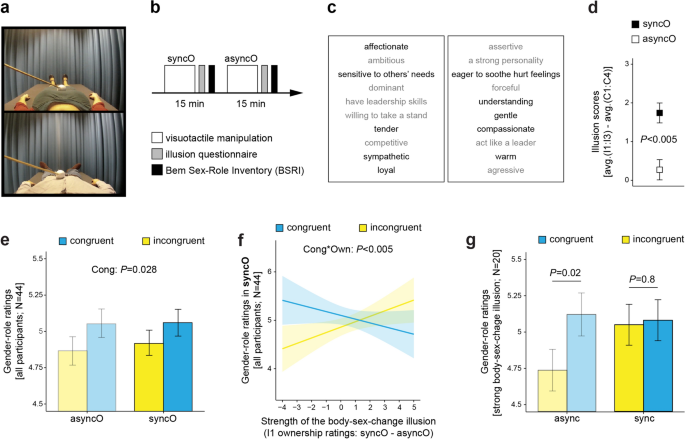

Contextualism holds that the features that determine our gender vary from context to context and so whether our gender identity determines our gender varies from context to context. Invariantist views such as gender identity first and the no connection view hold that one feature (e.g. gender identity or whether one is a sexually marked subordinate) determines our gender in every context. But we need not adopt such a monist invariantist view; we can instead adopt a pluralist invariantist view that holds that multiple features are relevant to, or determine, our genders across different contexts ( Figure 4 ). A version of pluralism that has been proposed is what we can call the two properties view. According to the two properties view, two and only two properties determine our gender in all contexts: our gender identity and our gendered social position or class. Gender identity first and Haslanger’s no connection view hold that one of these two properties determines our gender in every context; the two properties view holds that both of these properties can make us a particular gender in every context. 11

Views of the relationship between gender identity and gender

Katharine Jenkins (2016) proposes an ameliorative version of the two properties view. She proposes that we accept gender concepts according to which there are two senses of woman . In one sense of woman , to be a woman is to have a female gender identity; in another second sense, to be a woman is to be socially classed as a woman, which we can understand in terms of Haslanger’s account: to be a woman in this second sense is to be a sexually marked subordinate. Jenkins argues that if we accept gender concepts according to which there are two senses of ‘woman’, we do not objectionably exclude trans women, since trans women who are not socially classed as women do have female gender identities and so are still women on this view. So, Jenkins argues that we should accept gender concepts such that A is a woman iff A is socially classed as a woman or has a female gender identity. She then argues that, although we should accept gender concepts on which there are two senses of gender, we should, at least primarily, use ‘woman’ to refer to people with a female gender identity rather than those who are classed as women.

Jenkins’ two properties view avoids the problems with the ameliorative gender identity first and no connection views. It does not imply that severely cognitively disabled women are not women and it does not imply that trans women are not women. Yet if we adopt a concept of ‘woman’ with two senses but use ‘woman’ to refer to people with female gender identities, it still seems that we adopt concepts according to which trans women who are not socially classed as women are not women in an important sense. We may want to avoid this consequence with our ameliorative proposals, since trans women want to be thought of as women, and many trans women want to be thought of as in no way men, rather than merely being referred to as women rather than men (see e.g. Wynn 2018 ). We might also worry that adoption of Jenkins’ view would create a hierarchy of women on which someone who is a woman in both senses is more of a woman than someone who is a woman in only one sense: we might worry that if such concepts of gender were adopted, a trans woman who does not have her womanhood socially recognized would be seen as less of a woman than a trans woman who is socially positioned as a woman. 12

Elizabeth Barnes (2022 : 24–25) briefly articulates a similar metaphysical two properties view. On this view, there are two different properties that one can have that can make it the case that one is gender G : the property of being socially classed as a G and the property of having gender identity G . And the relevant gender identity property takes priority when A is socially classed as a G1 (e.g. as a man) but has gender identity G2 (e.g. a female gender identity): in such a case A is a G2 (a woman) rather than a G1 (a man) ( Figure 5 ).

The two properties view

However, the two properties view needs to explain why our gender identities take precedence over our gendered social position in determining our gender when the two conflict. Without further supplementation the metaphysical two property view does not do this; it does not explain why A is a man when A has a male gender identity but is socially positioned as a woman. If the two properties view does not explain this, it has an explanatory deficiency, and this deficiency gives us reason to accept competing views that do not face this explanatory problem over the two properties view.

One natural way to supplement the two properties view to try to solve this explanatory problem is to hold that moral and political considerations determine that gender identity takes priority over gender class when they conflict. 13 . First, it is controverisal that there is moral encroachment on gender metaphysics, that what's morally best makes a difference to what gender we metaphysically are. For instance, Ásta (2018) , Dembroff (2018) and Jenkins (2020) argue that morality does not encroach on gender metaphysics in this way.

Second, we can think of this as the moral encroachment explanation. However, moral encroachment does not look like a plausible explanation of how, metaphysically, gender identity takes priority over gendered social position in determining our genders. To see this, suppose that Alexa understands herself to be a woman and is treated by those around her as a woman. An evil demon will kill 2000 members of Alexa’s community unless we hold that Alexa is a man, treat Alexa as, think of Alexa as, and assert that Alexa is a man for the next hour. In this case, moral and political considerations establish that we morally ought to treat Alexa as a man for the next hour, but this doesn’t mean that Alexa is in fact a man. 14

It might seem that a nearby view on which moral and political considerations play a smaller role is more plausible. On this view, moral and political considerations only come in to determine whether, metaphysically, A is a member of gender G1 or of gender G2 when A is socially classed as a G1 but has identity G2 . But this view would also generate counterintuitive results. To see this, suppose that Beth has a female gender identity and she was assigned female at birth, but she is socially classed as a man – she doesn’t resist this because of the strong economic advantages she receives, which outweigh the discomfort she feels by being constantly misgendered. Now suppose that an eccentric, very powerful and malevolent millionaire brings these facts to light but will torture everyone in our society unless we continue to classify, think of and refer to Beth as a man. In this case, plausibly, moral and political considerations establish that we should classify Beth as a man, but these facts do not seem to bear on whether Beth is a man or a woman; intuitively Beth is a woman, and intuitively the fact that morally we should think of, treat, and classify Beth as a man does not make it the case that Beth is a man – and really has nothing to do with Beth’s gender in this case. So, if moral and political considerations play this more limited role in determining our genders, they still sometimes generate the wrong result because there are cases in which the social and political considerations side with someone’s gendered social position rather than their gender identity, but in which this does not seem to be relevant to, or establish that, their gender lines up with their gendered social position. So, the moral encroachment explanation does not seem to solve the explanatory problem for the two properties view. 15

These evil millionaire cases may be too fantastical for some. But the same point can be made with real world examples too. Norah Vincent (2006) disguised herself as a man for 18 months so that she could investigate men and their experiences. She became socially positioned as, and treated by others as, a man. While she was effectively disguised as a man, moral and political considerations seem to have established that everyone should treat her as a man: those who didn’t know her real gender had an obligation to take her assertions that she was a man as genuine and those who did know her real gender had an obligation not to blow her cover. But although everyone ought to have treated Vincent as a man, she was not a man: she did not identify as a man at the time, nor prior or subsequent to her journalistic project. Moral and political considerations favoured treating Vincent in line with her social position as a man rather than in line with her female gender identity. But these factors do not establish that she was a man rather than a woman. So, the moral encroachment explanation generates the wrong results in this case too.

One way to respond to this problem for the two properties view is to drop the view that gender identity takes priority. But this would be problematic for then trans women who are socially positioned as men would be both men and women on this view – and not just people with female gender identities who are socially positioned as men. This is implausible. This view is also different from contextualism since contextualism holds that such trans women are women-relative-to-the-standards-of-trans-inclusive-contexts and men-relative-to-other-contexts; a version of the two properties view that drops the priority of gender identity holds that such trans women are both men and women tout court .

In this paper I’ve discussed metaphysical and ameliorative inquiries into the relationship between gender identity and gender. I’ve discussed four different views about this relationship. All four views face problematic objections. Gender identity first seems to objectionably exclude some severely cognitively disabled people from having genders. No connection views seem to be objectionably trans exclusionary. Contextualism seems to be in tension with how we think about gender and implies that trans people are not the genders that line up with their gender identities in many contexts; despite contextualists’ best efforts, these implications still seem problematic. Pluralist views struggle to plausibly explain how their plurality of features interact when they conflict to determine our genders.

One avenue of future research involves examining the extent to which these objections really undermine these different views. For instance, we might question whether Barnes really shows that we should reject gender identity first. Barnes has two arguments for the view that, contra gender identity first, severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders.