- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Understanding the Milgram Experiment in Psychology

A closer look at Milgram's controversial studies of obedience

Isabelle Adam (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) via Flickr

Factors That Influence Obedience

- Ethical Concerns

- Replications

How far do you think people would go to obey an authority figure? Would they refuse to obey if the order went against their values or social expectations? Those questions were at the heart of an infamous and controversial study known as the Milgram obedience experiments.

Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted these experiments during the 1960s. They explored the effects of authority on obedience. In the experiments, an authority figure ordered participants to deliver what they believed were dangerous electrical shocks to another person. These results suggested that people are highly influenced by authority and highly obedient . More recent investigations cast doubt on some of the implications of Milgram's findings and even the results and procedures themselves. Despite its problems, the study has, without question, made a significant impact on psychology .

At a Glance

Milgram's experiments posed the question: Would people obey orders, even if they believed doing so would harm another person? Milgram's findings suggested the answer was yes, they would. The experiments have long been controversial, both because of the startling findings and the ethical problems with the research. More recently, experts have re-examined the studies, suggesting that participants were often coerced into obeying and that at least some participants recognized that the other person was just pretending to be shocked. Such findings call into question the study's validity and authenticity, but some replications suggest that people are surprisingly prone to obeying authority.

History of the Milgram Experiments

Milgram started his experiments in 1961, shortly after the trial of the World War II criminal Adolf Eichmann had begun. Eichmann’s defense that he was merely following instructions when he ordered the deaths of millions of Jews roused Milgram’s interest.

In his 1974 book "Obedience to Authority," Milgram posed the question, "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?"

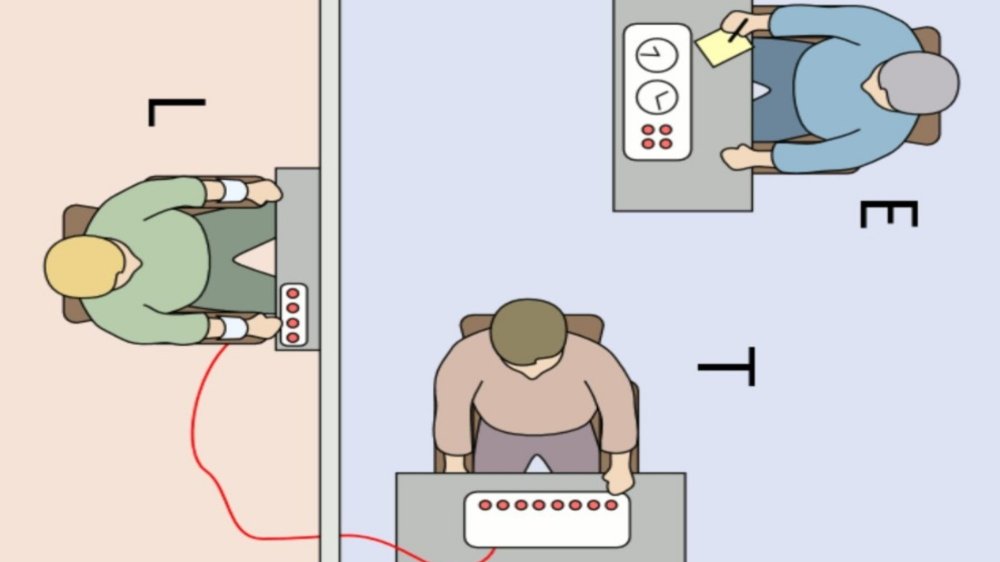

Procedure in the Milgram Experiment

The participants in the most famous variation of the Milgram experiment were 40 men recruited using newspaper ads. In exchange for their participation, each person was paid $4.50.

Milgram developed an intimidating shock generator, with shock levels starting at 15 volts and increasing in 15-volt increments all the way up to 450 volts. The many switches were labeled with terms including "slight shock," "moderate shock," and "danger: severe shock." The final three switches were labeled simply with an ominous "XXX."

Each participant took the role of a "teacher" who would then deliver a shock to the "student" in a neighboring room whenever an incorrect answer was given. While participants believed that they were delivering real shocks to the student, the “student” was a confederate in the experiment who was only pretending to be shocked.

As the experiment progressed, the participant would hear the learner plead to be released or even complain about a heart condition. Once they reached the 300-volt level, the learner would bang on the wall and demand to be released.

Beyond this point, the learner became completely silent and refused to answer any more questions. The experimenter then instructed the participant to treat this silence as an incorrect response and deliver a further shock.

Most participants asked the experimenter whether they should continue. The experimenter then responded with a series of commands to prod the participant along:

- "Please continue."

- "The experiment requires that you continue."

- "It is absolutely essential that you continue."

- "You have no other choice; you must go on."

Results of the Milgram Experiment

In the Milgram experiment, obedience was measured by the level of shock that the participant was willing to deliver. While many of the subjects became extremely agitated, distraught, and angry at the experimenter, they nevertheless continued to follow orders all the way to the end.

Milgram's results showed that 65% of the participants in the study delivered the maximum shocks. Of the 40 participants in the study, 26 delivered the maximum shocks, while 14 stopped before reaching the highest levels.

Why did so many of the participants in this experiment perform a seemingly brutal act when instructed by an authority figure? According to Milgram, there are some situational factors that can explain such high levels of obedience:

- The physical presence of an authority figure dramatically increased compliance .

- The fact that Yale (a trusted and authoritative academic institution) sponsored the study led many participants to believe that the experiment must be safe.

- The selection of teacher and learner status seemed random.

- Participants assumed that the experimenter was a competent expert.

- The shocks were said to be painful, not dangerous.

Later experiments conducted by Milgram indicated that the presence of rebellious peers dramatically reduced obedience levels. When other people refused to go along with the experimenter's orders, 36 out of 40 participants refused to deliver the maximum shocks.

More recent work by researchers suggests that while people do tend to obey authority figures, the process is not necessarily as cut-and-dried as Milgram depicted it.

In a 2012 essay published in PLoS Biology , researchers suggested that the degree to which people are willing to obey the questionable orders of an authority figure depends largely on two key factors:

- How much the individual agrees with the orders

- How much they identify with the person giving the orders

While it is clear that people are often far more susceptible to influence, persuasion , and obedience than they would often like to be, they are far from mindless machines just taking orders.

Another study that analyzed Milgram's results concluded that eight factors influenced the likelihood that people would progress up to the 450-volt shock:

- The experimenter's directiveness

- Legitimacy and consistency

- Group pressure to disobey

- Indirectness of proximity

- Intimacy of the relation between the teacher and learner

- Distance between the teacher and learner

Ethical Concerns in the Milgram Experiment

Milgram's experiments have long been the source of considerable criticism and controversy. From the get-go, the ethics of his experiments were highly dubious. Participants were subjected to significant psychological and emotional distress.

Some of the major ethical issues in the experiment were related to:

- The use of deception

- The lack of protection for the participants who were involved

- Pressure from the experimenter to continue even after asking to stop, interfering with participants' right to withdraw

Due to concerns about the amount of anxiety experienced by many of the participants, everyone was supposedly debriefed at the end of the experiment. The researchers reported that they explained the procedures and the use of deception.

Critics of the study have argued that many of the participants were still confused about the exact nature of the experiment, and recent findings suggest that many participants were not debriefed at all.

Replications of the Milgram Experiment

While Milgram’s research raised serious ethical questions about the use of human subjects in psychology experiments , his results have also been consistently replicated in further experiments. One review further research on obedience and found that Milgram’s findings hold true in other experiments. In one study, researchers conducted a study designed to replicate Milgram's classic obedience experiment. The researchers made several alterations to Milgram's experiment.

- The maximum shock level was 150 volts as opposed to the original 450 volts.

- Participants were also carefully screened to eliminate those who might experience adverse reactions to the experiment.

The results of the new experiment revealed that participants obeyed at roughly the same rate that they did when Milgram conducted his original study more than 40 years ago.

Some psychologists suggested that in spite of the changes made in the replication, the study still had merit and could be used to further explore some of the situational factors that also influenced the results of Milgram's study. But other psychologists suggested that the replication was too dissimilar to Milgram's original study to draw any meaningful comparisons.

One study examined people's beliefs about how they would do compared to the participants in Milgram's experiments. They found that most people believed they would stop sooner than the average participants. These findings applied to both those who had never heard of Milgram's experiments and those who were familiar with them. In fact, those who knew about Milgram's experiments actually believed that they would stop even sooner than other people.

Another novel replication involved recruiting participants in pairs and having them take turns acting as either an 'agent' or 'victim.' Agents then received orders to shock the victim. The results suggest that only around 3.3% disobeyed the experimenter's orders.

Recent Criticisms and New Findings

Psychologist Gina Perry suggests that much of what we think we know about Milgram's famous experiments is only part of the story. While researching an article on the topic, she stumbled across hundreds of audiotapes found in Yale archives that documented numerous variations of Milgram's shock experiments.

Participants Were Often Coerced

While Milgram's reports of his process report methodical and uniform procedures, the audiotapes reveal something different. During the experimental sessions, the experimenters often went off-script and coerced the subjects into continuing the shocks.

"The slavish obedience to authority we have come to associate with Milgram’s experiments comes to sound much more like bullying and coercion when you listen to these recordings," Perry suggested in an article for Discover Magazine .

Few Participants Were Really Debriefed

Milgram suggested that the subjects were "de-hoaxed" after the experiments. He claimed he later surveyed the participants and found that 84% were glad to have participated, while only 1% regretted their involvement.

However, Perry's findings revealed that of the 700 or so people who took part in different variations of his studies between 1961 and 1962, very few were truly debriefed.

A true debriefing would have involved explaining that the shocks weren't real and that the other person was not injured. Instead, Milgram's sessions were mainly focused on calming the subjects down before sending them on their way.

Many participants left the experiment in a state of considerable distress. While the truth was revealed to some months or even years later, many were simply never told a thing.

Variations Led to Differing Results

Another problem is that the version of the study presented by Milgram and the one that's most often retold does not tell the whole story. The statistic that 65% of people obeyed orders applied only to one variation of the experiment, in which 26 out of 40 subjects obeyed.

In other variations, far fewer people were willing to follow the experimenters' orders, and in some versions of the study, not a single participant obeyed.

Participants Guessed the Learner Was Faking

Perry even tracked down some of the people who took part in the experiments, as well as Milgram's research assistants. What she discovered is that many of his subjects had deduced what Milgram's intent was and knew that the "learner" was merely pretending.

Such findings cast Milgram's results in a new light. It suggests that not only did Milgram intentionally engage in some hefty misdirection to obtain the results he wanted but that many of his participants were simply playing along.

An analysis of an unpublished study by Milgram's assistant, Taketo Murata, found that participants who believed they were really delivering a shock were less likely to obey, while those who did not believe they were actually inflicting pain were more willing to obey. In other words, the perception of pain increased defiance, while skepticism of pain increased obedience.

A review of Milgram's research materials suggests that the experiments exerted more pressure to obey than the original results suggested. Other variations of the experiment revealed much lower rates of obedience, and many of the participants actually altered their behavior when they guessed the true nature of the experiment.

Impact of the Milgram Experiment

Since there is no way to truly replicate the experiment due to its serious ethical and moral problems, determining whether Milgram's experiment really tells us anything about the power of obedience is impossible to determine.

So why does Milgram's experiment maintain such a powerful hold on our imaginations, even decades after the fact? Perry believes that despite all its ethical issues and the problem of never truly being able to replicate Milgram's procedures, the study has taken on the role of what she calls a "powerful parable."

Milgram's work might not hold the answers to what makes people obey or even the degree to which they truly obey. It has, however, inspired other researchers to explore what makes people follow orders and, perhaps more importantly, what leads them to question authority.

Recent findings undermine the scientific validity of the study. Milgram's work is also not truly replicable due to its ethical problems. However, the study has led to additional research on how situational factors can affect obedience to authority.

Milgram’s experiment has become a classic in psychology , demonstrating the dangers of obedience. The research suggests that situational variables have a stronger sway than personality factors in determining whether people will obey an authority figure. However, other psychologists argue that both external and internal factors heavily influence obedience, such as personal beliefs and overall temperament.

Milgram S. Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. Harper & Row.

Russell N, Gregory R. The Milgram-Holocaust linkage: challenging the present consensus . State Crim J. 2015;4(2):128-153.

Russell NJC. Milgram's obedience to authority experiments: origins and early evolution . Br J Soc Psychol . 2011;50:140-162. doi:10.1348/014466610X492205

Haslam SA, Reicher SD. Contesting the "nature" of conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo's studies really show . PLoS Biol. 2012;10(11):e1001426. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001426

Milgram S. Liberating effects of group pressure . J Person Soc Psychol. 1965;1(2):127-234. doi:10.1037/h0021650

Haslam N, Loughnan S, Perry G. Meta-Milgram: an empirical synthesis of the obedience experiments . PLoS One . 2014;9(4):e93927. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093927

Perry G. Deception and illusion in Milgram's accounts of the obedience experiments . Theory Appl Ethics . 2013;2(2):79-92.

Blass T. The Milgram paradigm after 35 years: some things we now know about obedience to authority . J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(5):955-978. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00134.x

Burger J. Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? . Am Psychol . 2009;64(1):1-11. doi:10.1037/a0010932

Elms AC. Obedience lite . American Psychologist . 2009;64(1):32-36. doi:10.1037/a0014473

Miller AG. Reflections on “replicating Milgram” (Burger, 2009) . American Psychologist . 2009;64(1):20-27. doi:10.1037/a0014407

Grzyb T, Dolinski D. Beliefs about obedience levels in studies conducted within the Milgram paradigm: Better than average effect and comparisons of typical behaviors by residents of various nations . Front Psychol . 2017;8:1632. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01632

Caspar EA. A novel experimental approach to study disobedience to authority . Sci Rep . 2021;11(1):22927. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-02334-8

Haslam SA, Reicher SD, Millard K, McDonald R. ‘Happy to have been of service’: The Yale archive as a window into the engaged followership of participants in Milgram’s ‘obedience’ experiments . Br J Soc Psychol . 2015;54:55-83. doi:10.1111/bjso.12074

Perry G, Brannigan A, Wanner RA, Stam H. Credibility and incredulity in Milgram’s obedience experiments: A reanalysis of an unpublished test . Soc Psychol Q . 2020;83(1):88-106. doi:10.1177/0190272519861952

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How Would People Behave in Milgram’s Experiment Today?

Photo from the Milgram Experiment.

More than fifty years ago, then Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted the famous—or infamous—experiments on destructive obedience that have come to be known as “Milgram’s shocking experiments” (pun usually intended). Milgram began his experiments in July 1961, the same month that the trial of Adolf Eichmann—the German bureaucrat responsible for transporting Jews to the extermination camps during the Holocaust—concluded in Jerusalem. The trial was made famous by the philosopher Hannah Arendt’s reports, later published in book form as Eichmann in Jerusalem . Arendt claimed that Eichmann was a colorless bureaucrat who blandly followed orders without much thought for the consequences, and whose obedient behavior demonstrated the “banality of evil.”

Milgram himself was Jewish, and his original question was whether nations other than Germany would differ in their degrees of conformity to authority. He assumed that the citizens of America, home of rugged individualism and apple pie, would display much lower levels of conformity when commanded by authorities to engage in behavior that might harm others. His Yale experiments were designed to set a national baseline.

Half of a century after Milgram probed the nature of destructive obedience to authority, we are faced with the unsettling question: What would citizens do today?

The Original Experiment

In Milgram’s original experiment, participants took part in what they thought was a “learning task.” This task was designed to investigate how punishment—in this case in the form of electric shocks—affected learning. Volunteers thought they were participating in pairs, but their partner was in fact a confederate of the experimenter. A draw to determine who would be the “teacher” and who would be the “learner” was rigged; the true volunteer always ended up as the teacher and the confederate as learner.

The pairs were moved into separate rooms, connected by a microphone. The teacher read aloud a series of word pairs, such as “red–hammer,” which the learner was instructed to memorize. The teacher then read the target word (red), and the learner was to select the original paired word from four alternatives (ocean, fan, hammer, glue).

Did Milgram’s experiment demonstrate that humans have a universal propensity to destructive obedience or that they are merely products of their cultural moment?

If the learner erred, the teacher was instructed to deliver an electric shock as punishment, increasing the shock by 15-volt increments with each successive error. Although the teacher could not see the learner in the adjacent room, he could hear his responses to the shocks as well as to the questions. According to a prearranged script, at 75 volts, the learner started to scream; from 150 volts to 330 volts, he protested with increasing intensity, complaining that his heart was bothering him; at 330 volts, he absolutely refused to go on. After that the teacher’s questions were met by silence. Whenever the teacher hesitated, the experimenter pressed the teacher to continue, insisting that the “the experiment requires that you continue” and reminding him that “although the shocks may be painful, they cause no permanent tissue damage.”

Milgram was horrified by the results of the experiment . In the “remote condition” version of the experiment described above, 65 percent of the subjects (26 out of 40) continued to inflict shocks right up to the 450-volt level, despite the learner’s screams, protests, and, at the 330-volt level, disturbing silence. Moreover, once participants had reached 450 volts, they obeyed the experimenter’s instruction to deliver 450-volt shocks when the subject continued to fail to respond.

Putting Milgram’s Work in Context

Milgram’s experiment became the subject of a host of moral and methodological critiques in the 1960s. These became somewhat moot with the publication of the American Psychological Association’s ethical principles of research with human subjects in 1973 and the restrictions on the use of human subjects included in the National Research Act of 1974, which effectively precluded psychologists from conducting experiments that, like Milgram’s, were likely to cause serious distress to subjects. This was undoubtedly a good thing for experimental subjects, but it also blocked attempts to answer a question that many were asking: Did Milgram’s experiment demonstrate that humans have a universal propensity to destructive obedience or that they are merely products of their cultural moment?

Cross-cultural studies at the time provided a partial answer. The U.S. mean obedience rate of 60.94 percent was not significantly different from the foreign mean obedience rate of 65.94 percent, although there was wide variation in the results (rates ranged from 31 to 91 percent in the U.S. and from 28 to 87.5 percent in foreign studies) and design of the studies. However, a historical question remained: Would subjects today still display the same levels of destructive obedience as the subjects of fifty years ago?

There are grounds to believe they would not. In the 1950s, psychologists and the general public were shocked by the results of Solomon Asch’s experiments on conformity . In a series of line-judgement studies, subjects were asked to decide which of three comparison lines matched a target line. Crucially, these judgements were made in a social context, among other participants. Only one of the subjects in the experiment was a naive subject, while the other six were confederates of the experimenter instructed to give incorrect answers. When they gave answers that were incorrect, and seemed plainly incorrect to the naive subjects, about one-third of the naive subjects gave answers that conformed with the majority. In other words, people were happy to ignore the evidence before their eyes in order to conform to the group consensus.

For some observers, these results threatened America’s image as the land of individualism and autonomy. Yet in the 1980s, replications of Asch’s experiment failed to detect even minimal levels of conformity, suggesting that Asch’s results were a child of 1950s, the age of “other-directed” people made famous by David Reisman in his 1950 work The Lonely Crowd . Might the same failure to replicate be true today if people faced Milgram’s experiment anew?

Understanding Milgram’s Work Today

Although full replications of Milgram’s experiment are precluded in the United States because of ethical and legal constraints on experimenters, there have been replications attempted in other countries, and attempts by U.S. experimenters to sidestep these constraints.

A replication conducted by Dariusz Dolinski and colleagues in 2015 generated levels of obedience higher than the original Milgram experiment , although the study may be criticized because it employed lower levels of shock.

More intriguing was the 2009 replication by Jerry Burger, who found an ingenious way of navigating the ethical concerns about Milgram’s original experiment . Burger noted that in the original experiment 79 percent of subjects who continued after the 150 volts—after the learner’s first screams—continued all the way to the end of the scale, at 450 volts. Assuming that the same would be true of subjects today, Burger determined how many were willing to deliver shocks beyond the 150-volt level, at which point the experiment was discontinued.

Given social support, most subjects refused to continue to administer shocks, suggesting that social solidarity serves as a kind of a defense against destructive obedience to authority.

About 70 percent were willing to continue the experiment at this point, suggesting that subjects remain just as compliant in the 21st century. Nonetheless, Burger’s study was based upon a questionable assumption, namely that 150-volt compliance has remained a reliable predictor of 450-volt compliance. Subjects today might be willing to go a bit beyond 150 volts, but perhaps not to the far end of the scale (after learners demand that the experiment be discontinued etc.). In fact, this assumption begs the critical question at issue.

However, French television came to the rescue. One game show replicated Milgram’s experiment , with the game show host as the authority and the “questioner” as the subject. In a study reported in the 2012 European Review of Applied Psychology , J.-L. Beauvois and colleagues replicated Milgram’s voice feedback condition , with identical props, instructions, and scripted learner responses and host prods. One might question whether a game show host has as much authority as a scientific experimenter, but whatever authority they had managed to elicit levels of obedience equivalent to Milgram’s original experiment (in fact somewhat higher, 81 percent as opposed to the original 65 percent). It would seem that at least French nationals are as compliant today as Milgram’s original subjects in the 1960s.

In fact, the replication suggests a darker picture. One of the optimistic findings of the original Milgram experiment was his condition 7, in which there were three teachers, two of whom (both confederates of the experimenter) defied the experimenter. Given this social support, most subjects refused to continue to administer shocks, suggesting that social solidarity serves as a kind of a defense against destructive obedience to authority. Unfortunately, this did not occur in the French replication, in which the production assistant protested about the immorality of the procedure with virtually no effect on levels of obedience. And unfortunately, not in the Burger study either: Burger found that the intervention of an accomplice who refused to continue had no effect on the levels of obedience. So it may be that we are in fact more compliant today than Milgram’s original subjects, unmoved by social support. A dark thought for our dark times.

What Does Boredom Teach Us About How We Engage with History?

The Surprising Origins of Our Obsession with Creativity

A New Look at the History of U.S. Immigration: A Conversation with Ran Abramitzky

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

Milgram experiment

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Open University - OpenLearn - Psychological research, obedience and ethics: 1 Milgram’s obedience study

- Social Science LibreTexts - The Milgram Experiment- The Power of Authority

- Verywell Mind - What was the Milgram Experiment?

- BCcampus Open Publishing - Ethics in Law Enforcement - The Milgram Experiment

- Nature - Modern Milgram experiment sheds light on power of authority

- SimplyPsychology - Stanley Milgram Shock Experiment: Summary, Results, & Ethics

- University of California - College of Natural Resources - Milgrams Experiment on Obedience to Authority

Milgram experiment , controversial series of experiments examining obedience to authority conducted by social psychologist Stanley Milgram . In the experiment, an authority figure, the conductor of the experiment, would instruct a volunteer participant, labeled the “teacher,” to administer painful, even dangerous, electric shocks to the “learner,” who was actually an actor. Although the shocks were faked, the experiments are widely considered unethical today due to the lack of proper disclosure, informed consent, and subsequent debriefing related to the deception and trauma experienced by the teachers. Some of Milgram’s conclusions have been called into question. Nevertheless, the experiments and their results have been widely cited for their insight into how average people respond to authority.

Milgram conducted his experiments as an assistant professor at Yale University in the early 1960s. In 1961 he began to recruit men from New Haven , Connecticut , for participation in a study he claimed would be focused on memory and learning . The recruits were paid $4.50 at the beginning of the study and were generally between the ages of 20 and 50 and from a variety of employment backgrounds. When they volunteered, they were told that the experiment would test the effect of punishment on learning ability. In truth, the volunteers were the subjects of an experiment on obedience to authority. In all, about 780 people, only about 40 of them women, participated in the experiments, and Milgram published his results in 1963.

Volunteers were told that they would be randomly assigned either a “teacher” or “learner” role, with each teacher administering electric shocks to a learner in another room if the learner failed to answer questions correctly. In actuality, the random draw was fixed so that all the volunteer participants were assigned to the teacher role and the actors were assigned to the learner role. The teachers were then instructed in the electroshock “punishment” they would be administering, with 30 shock levels ranging from 15 to 450 volts. The different shock levels were labeled with descriptions of their effects, such as “Slight Shock,” “Intense Shock,” and “Danger: Severe Shock,” with the final label a grim “XXX.” Each teacher was given a 45-volt shock themselves so that they would better understand the punishment they believed the learner would be receiving. Teachers were then given a series of questions for the learner to answer, with each incorrect answer generally earning the learner a progressively stronger shock. The actor portraying the learner, who was seated out of sight of the teacher, had pre-recorded responses to these shocks that ranged from grunts of pain to screaming and pleading, claims of suffering a heart condition, and eventually dead silence. The experimenter, acting as an authority figure, would encourage the teachers to continue administering shocks, telling them with scripted responses that the experiment must continue despite the reactions of the learner. The infamous result of these experiments was that a disturbingly high number of the teachers were willing to proceed to the maximum voltage level, despite the pleas of the learner and the supposed danger of proceeding.

Milgram’s interest in the subject of authority, and his dark view of the results of his experiments, were deeply informed by his Jewish identity and the context of the Holocaust , which had occurred only a few years before. He had expected that Americans, known for their individualism , would differ from Germans in their willingness to obey authority when it might lead to harming others. Milgram and his students had predicted only 1–3% of participants would administer the maximum shock level. However, in his first official study, 26 of 40 male participants (65%) were convinced to do so and nearly 80% of teachers that continued to administer shocks after 150 volts—the point at which the learner was heard to scream—continued to the maximum of 450 volts. Teachers displayed a range of negative emotional responses to the experiment even as they continued to obey, sometimes pleading with the experimenters to stop the experiment while still participating in it. One teacher believed that he had killed the learner and was moved to tears when he eventually found out that he had not.

Milgram included several variants on the original design of the experiment. In one, the teachers were allowed to select their own voltage levels. In this case, only about 2.5% of participants used the maximum shock level, indicating that they were not inclined to do so without the prompting of an authority figure. In another, there were three teachers, two of whom were not test subjects, but instead had been instructed to protest against the shocks. The existence of peers protesting the experiment made the volunteer teachers less likely to obey. Teachers were also less likely to obey in a variant where they could see the learner and were forced to interact with him.

The Milgram experiment has been highly controversial, both for the ethics of its design and for the reliability of its results and conclusions. It is commonly accepted that the ethics of the experiment would be rejected by mainstream science today, due not only to the handling of the deception involved but also to the extreme stress placed on the teachers, who often reacted emotionally to the experiment and were not debriefed . Some teachers were actually left believing they had genuinely and repeatedly shocked a learner before having the truth revealed to them later. Later researchers examining Milgram’s data also found that the experimenters conducting the tests had sometimes gone off-script in their attempts to coerce the teachers into continuing, and noted that some teachers guessed that they were the subjects of the experiment. However, attempts to validate Milgram’s findings in more ethical ways have often produced similar results.

The Milgram Experiment: How Far Will You Go to Obey an Order?

Understand the infamous study and its conclusions about human nature

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Psychology, University of California - Santa Barbara

- B.A., Psychology and Peace & Conflict Studies, University of California - Berkeley

A brief Milgram experiment summary is as follows: In the 1960s, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted a series of studies on the concepts of obedience and authority. His experiments involved instructing study participants to deliver increasingly high-voltage shocks to an actor in another room, who would scream and eventually go silent as the shocks became stronger. The shocks weren't real, but study participants were made to believe that they were.

Today, the Milgram experiment is widely criticized on both ethical and scientific grounds. However, Milgram's conclusions about humanity's willingness to obey authority figures remain influential and well-known.

Key Takeaways: The Milgram Experiment

- The goal of the Milgram experiment was to test the extent of humans' willingness to obey orders from an authority figure.

- Participants were told by an experimenter to administer increasingly powerful electric shocks to another individual. Unbeknownst to the participants, shocks were fake and the individual being shocked was an actor.

- The majority of participants obeyed, even when the individual being shocked screamed in pain.

- The experiment has been widely criticized on ethical and scientific grounds.

Detailed Milgram’s Experiment Summary

In the most well-known version of the Milgram experiment, the 40 male participants were told that the experiment focused on the relationship between punishment, learning, and memory. The experimenter then introduced each participant to a second individual, explaining that this second individual was participating in the study as well. Participants were told that they would be randomly assigned to roles of "teacher" and "learner." However, the "second individual" was an actor hired by the research team, and the study was set up so that the true participant would always be assigned to the "teacher" role.

During the Milgram experiment, the learner was located in a separate room from the teacher (the real participant), but the teacher could hear the learner through the wall. The experimenter told the teacher that the learner would memorize word pairs and instructed the teacher to ask the learner questions. If the learner responded incorrectly to a question, the teacher would be asked to administer an electric shock. The shocks started at a relatively mild level (15 volts) but increased in 15-volt increments up to 450 volts. (In actuality, the shocks were fake, but the participant was led to believe they were real.)

Participants were instructed to give a higher shock to the learner with each wrong answer. When the 150-volt shock was administered, the learner would cry out in pain and ask to leave the study. He would then continue crying out with each shock until the 330-volt level, at which point he would stop responding.

During this process, whenever participants expressed hesitation about continuing with the study, the experimenter would urge them to go on with increasingly firm instructions, culminating in the statement, "You have no other choice, you must go on." The study ended when participants refused to obey the experimenter’s demand, or when they gave the learner the highest level of shock on the machine (450 volts).

Milgram found that participants obeyed the experimenter at an unexpectedly high rate: 65% of the participants gave the learner the 450-volt shock.

Critiques of the Milgram Experiment

The Milgram experiment has been widely criticized on ethical grounds. Milgram’s participants were led to believe that they acted in a way that harmed someone else, an experience that could have had long-term consequences. Moreover, an investigation by writer Gina Perry uncovered that some participants appear to not have been fully debriefed after the study —they were told months later, or not at all, that the shocks were fake and the learner wasn’t harmed. Milgram’s studies could not be perfectly recreated today, because researchers today are required to pay much more attention to the safety and well-being of human research subjects.

Researchers have also questioned the scientific validity of Milgram’s results. In her examination of the study, Perry found that Milgram’s experimenter may have gone off script and told participants to obey many more times than the script specified. Additionally, some research suggests that participants may have figured out that the learner was not harmed: in interviews conducted after the Milgram experiment, some participants reported that they didn’t think the learner was in any real danger. This mindset is likely to have affected their behavior in the study.

Variations on the Milgram Experiment

Milgram and other researchers conducted numerous versions of the experiment over time. The participants' levels of compliance with the experimenter’s demands varied greatly from one study to the next. For example, when participants were in closer proximity to the learner (e.g. in the same room), they were less likely to give the learner the highest level of shock.

Another version of the Milgram experiment brought three "teachers" into the experiment room at once. One was a real participant, and the other two were actors hired by the research team. During the experiment, the two non-participant teachers would quit as the level of shocks began to increase. Milgram found that these conditions made the real participant far more likely to "disobey" the experimenter, too: only 10% of participants gave the 450-volt shock to the learner.

In yet another version of the Milgram experiment, two experimenters were present, and during the experiment, they would begin arguing with one another about whether it was right to continue the study. In this version, none of the participants gave the learner the 450-volt shock.

Replicating the Milgram Experiment

Researchers have sought to replicate Milgram's original study with additional safeguards in place to protect participants. In 2009, Jerry Burger replicated Milgram’s famous experiment at Santa Clara University with new safeguards in place: the highest shock level was 150 volts, and participants were told that the shocks were fake immediately after the experiment ended. Additionally, participants were screened by a clinical psychologist before the experiment began, and those found to be at risk of a negative reaction to the study were deemed ineligible to participate.

Burger found that participants obeyed at similar levels as Milgram’s participants: 82.5% of Milgram’s participants gave the learner the 150-volt shock, and 70% of Burger’s participants did the same.

The Legacy of the Milgram Experiment

Milgram’s interpretation of his research was that everyday people are capable of carrying out unthinkable actions in certain circumstances. His research has been used to explain atrocities such as the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide, though these applications are by no means widely accepted or agreed upon.

Importantly, not all participants obeyed the experimenter’s demands , and Milgram’s studies shed light on the factors that enable people to stand up to authority. In fact, as sociologist Matthew Hollander writes, we may be able to learn from the participants who disobeyed, as their strategies may enable us to respond more effectively to an unethical situation. The Milgram experiment suggested that human beings are susceptible to obeying authority, but it also demonstrated that obedience is not inevitable.

- Baker, Peter C. “Electric Schlock: Did Stanley Milgram's Famous Obedience Experiments Prove Anything?” Pacific Standard (2013, Sep. 10). https://psmag.com/social-justice/electric-schlock-65377

- Burger, Jerry M. "Replicating Milgram: Would People Still Obey Today?." American Psychologist 64.1 (2009): 1-11. http://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2008-19206-001

- Gilovich, Thomas, Dacher Keltner, and Richard E. Nisbett. Social Psychology . 1st edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006.

- Hollander, Matthew. “How to Be a Hero: Insight From the Milgram Experiment.” HuffPost Contributor Network (2015, Apr. 29). https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/how-to-be-a-hero-insight-_b_6566882

- Jarrett, Christian. “New Analysis Suggests Most Milgram Participants Realised the ‘Obedience Experiments’ Were Not Really Dangerous.” The British Psychological Society: Research Digest (2017, Dec. 12). https://digest.bps.org.uk/2017/12/12/interviews-with-milgram-participants-provide-little-support-for-the-contemporary-theory-of-engaged-followership/

- Perry, Gina. “The Shocking Truth of the Notorious Milgram Obedience Experiments.” Discover Magazine Blogs (2013, Oct. 2). http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/crux/2013/10/02/the-shocking-truth-of-the-notorious-milgram-obedience-experiments/

- Romm, Cari. “Rethinking One of Psychology's Most Infamous Experiments.” The Atlantic (2015, Jan. 28) . https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/01/rethinking-one-of-psychologys-most-infamous-experiments/384913/

- Gilligan's Ethics of Care

- What Is Behaviorism in Psychology?

- What Was the Robbers Cave Experiment in Psychology?

- What Is the Zeigarnik Effect? Definition and Examples

- What Is a Conditioned Response?

- Psychodynamic Theory: Approaches and Proponents

- Social Cognitive Theory: How We Learn From the Behavior of Others

- Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development

- What's the Difference Between Eudaimonic and Hedonic Happiness?

- Genie Wiley, the Feral Child

- What Is the Law of Effect in Psychology?

- What Is the Recency Effect in Psychology?

- Heuristics: The Psychology of Mental Shortcuts

- What Is Survivor's Guilt? Definition and Examples

- 5 Psychology Studies That Will Make You Feel Good About Humanity

- What Is Cognitive Bias? Definition and Examples

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

Taking a closer look at milgram's shocking obedience study.

Behind the Shock Machine

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

In the early 1960s, Stanley Milgram, a social psychologist at Yale, conducted a series of experiments that became famous. Unsuspecting Americans were recruited for what purportedly was an experiment in learning. A man who pretended to be a recruit himself was wired up to a phony machine that supposedly administered shocks. He was the "learner." In some versions of the experiment he was in an adjoining room.

The unsuspecting subject of the experiment, the "teacher," read lists of words that tested the learner's memory. Each time the learner got one wrong, which he intentionally did, the teacher was instructed by a man in a white lab coat to deliver a shock. With each wrong answer the voltage went up. From the other room came recorded and convincing protests from the learner — even though no shock was actually being administered.

The results of Milgram's experiment made news and contributed a dismaying piece of wisdom to the public at large: It was reported that almost two-thirds of the subjects were capable of delivering painful, possibly lethal shocks, if told to do so. We are as obedient as Nazi functionaries.

Or are we? Gina Perry, a psychologist from Australia, has written Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments . She has been retracing Milgram's steps, interviewing his subjects decades later.

"The thought of quitting never ... occurred to me," study participant Bill Menold told Perry in an Australian radio documentary . "Just to say: 'You know what? I'm walking out of here' — which I could have done. It was like being in a situation that you never thought you would be in, not really being able to think clearly."

In his experiments, Milgram was "looking to investigate what it was that had contributed to the brainwashing of American prisoners of war by the Chinese [in the Korean war]," Perry tells NPR's Robert Siegel.

Interview Highlights

On turning from an admirer of Milgram to a critic

"That was an unexpected outcome for me, really. I regarded Stanley Milgram as a misunderstood genius who'd been penalized in some ways for revealing something troubling and profound about human nature. By the end of my research I actually had quite a very different view of the man and the research."

Watch A Video Of One Of The Milgram Obedience Experiments

On the many variations of the experiment

"Over 700 people took part in the experiments. When the news of the experiment was first reported, and the shocking statistic that 65 percent of people went to maximum voltage on the shock machine was reported, very few people, I think, realized then and even realize today that that statistic applied to 26 of 40 people. Of those other 700-odd people, obedience rates varied enormously. In fact, there were variations of the experiment where no one obeyed."

On how Milgram's study coincided with the trial of Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann — and how the experiment reinforced what Hannah Arendt described as "the banality of evil"

"The Eichmann trial was a televised trial and it did reintroduce the whole idea of the Holocaust to a new American public. And Milgram very much, I think, believed that Hannah Arendt's view of Eichmann as a cog in a bureaucratic machine was something that was just as applicable to Americans in New Haven as it was to people in Germany."

On the ethics of working with human subjects

"Certainly for people in academia and scholars the ethical issues involved in Milgram's experiment have always been a hot issue. They were from the very beginning. And Milgram's experiment really ignited a debate particularly in social sciences about what was acceptable to put human subjects through."

Gina Perry is an Australian psychologist. She has previously written for The Age and The Australian. Chris Beck/Courtesy of The New Press hide caption

Gina Perry is an Australian psychologist. She has previously written for The Age and The Australian.

On conversations with the subjects, decades after the experiment

"[Bill Menold] doesn't sound resentful. I'd say he sounds thoughtful and he has reflected a lot on the experiment and the impact that it's had on him and what it meant at the time. I did interview someone else who had been disobedient in the experiment but still very much resented 50 years later that he'd never been de-hoaxed at the time and he found that really unacceptable."

On the problem that one of social psychology's most famous findings cannot be replicated

"I think it leaves social psychology in a difficult situation. ... it is such an iconic experiment. And I think it really leads to the question of why it is that we continue to refer to and believe in Milgram's results. I think the reason that Milgram's experiment is still so famous today is because in a way it's like a powerful parable. It's so widely known and so often quoted that it's taken on a life of its own. ... This experiment and this story about ourselves plays some role for us 50 years later."

Related NPR Stories

Shocking TV Experiment Sparks Ethical Concerns

How stanley milgram 'shocked the world', research news, scientists debate 'six degrees of separation'.

The Milgram Shock Experiment

Would you give someone a deadly electric shock? Would you follow orders to commit a violent crime against an innocent person? Would you support an unjust cause, just because you are told to?

People rarely see themselves as violent or capable of committing violent acts. People rarely see themselves on the wrong side of history. And yet, human history is full of violence, genocides, and atrocities. You might see friends and family now, people that you believe are good people, supporting violence. How does this happen?

I’m going to tell you about an experiment in psychology that set out to explain why people commit violence against others. And then I’ll ask you these questions again. The true answers to these questions might surprise you.

History of the Milgram Shock Study

This study is most commonly known as the Milgram Shock Study or the Milgram Experiment. Its name comes from Stanley Milgram, the psychologist behind the study.

Milgram was born in the 1930s in New York City to Jewish immigrant parents. As he grew up, he witnessed the atrocities of the Holocaust from thousands of miles away. How could people commit such atrocities? How could people see the horror in front of them and continue to participate in it?

These questions followed him as he became a psychologist at Yale University. In 1961, he decided to set up a study that might show how people follow orders from authority, even if it goes against their morals.

How Did the Study Work?

Over the course of two years, Milgram recruited men to participate in a study. Milgram created a few variations of the study, but in general, they involved the participant, a “learner,” and an experimenter. The participant acted as a “teacher,” reading out words to the learner. The learner would have to repeat the words back to the participant. If the learner got it wrong, the teacher had to deliver an electric shock.

These shocks increased in voltage. At first, the shocks were around 15 volts - just a mild sensation. But the shocks reached up to 450 volts, which is extremely dangerous. (Of course, these shocks weren’t real. The learner was an actor who played along with the study.)

The experimenter encouraged the participants to administer the shocks whenever the learner was incorrect. As the voltages increased, some participants resisted. In some variations of the study, the experimenter would urge the participants to administer the shocks. This happened in stages. Some participants were told to please continue, and eventually told that they had no choice but to continue.

In some variations of the study, the participant would beg the participant not to administer the shocks, complaining of a heart problem. The participant would even fake death once the highest voltages were reached.

Conclusions

You might be surprised to hear that this study even took place - there are obviously some ethical concerns behind asking participants to deliver dangerous electric shocks. The trauma of that study could impact participants, some of whom did not learn the truth about the study for months after it was over.

But you also might be surprised to hear that a lot of the participants did administer the most dangerous shocks.

After the experiment was complete, Milgram asked a group of his students how many participants they thought would deliver the highest shock. The students predicted 3%. But in the most well-known variation of the study, a shocking 65% of participants reached the highest level of shocks. All of the participants reached the 300-volt level.

Legacy of the Study

The Milgram Shock Study took place over 50 years ago, and it is still considered one of the most controversial and infamous studies in modern history. The study even inspired made-for-TV movies!

But not everyone praises Milgram for his boldness.

Critiques of the Study

The results of this study aren’t particularly optimistic, and there have been critiques from psychologists over the years. After all, Milgram’s selection of participants wasn’t perfect. All of the participants were male, a group that only represents 50% of the population. Would the results be different if women were asked to deliver the electric shocks? Another factor to consider is that, like in the Stanford Prison Experiment, all of the participants answered a newspaper ad to participate in the study for money. Would the results be different if the participants were not the type to volunteer for an unknown study?

Other critics believe that documentation of Milgram’s experiment suggest that some participants were coerced into completing the study. Psychologist Gina Perry believes that participants were even “bullied” into completing the study.

Perry also believes that Milgram failed to tell participants the truth about the study. Rather than telling participants that the learner was an actor and shocks were never delivered, experimenters simply allowed participants to calm down after the study and sent them home. Many were never told the truth. That’s not very ethical, especially when their participation could have meant injuring another person.

Replications

With most studies from 50 years ago, psychologists have attempted to retest Milgram’s theories. It’s been hard to replicate the study because of its controversial methods. But similar studies that have slightly tweaked Milgram’s methods have yielded similar results. Other replications take Milgram’s findings a step further. People are more obedient than they might seem.

Does this mean that we’re all bad people, just hiding under a mirage of sound judgement? Not exactly. Five years after the publication of Milgram’s experiment, psychologist Walter Mischel published Personality and Assessment. It suggested that trait theorists were looking at personality theory all wrong. Mischel suggested that different situations could drive different behaviors. Thus, situationism was born. Studies like Milgram’s experiment and the Stanford Prison Experiment are still considered supporting evidence of situationism.

So let me ask the questions that I asked at the beginning of this video. Would you give someone a deadly electric shock? Would you follow orders to commit a violent crime against an innocent person? Would you support an unjust cause, just because you are told to? Would it just depend on the situation?

Related posts:

- Stanley Milgram (Psychologist Biography)

- The Psychology of Long Distance Relationships

- The Monster Study (Summary, Results, and Ethical Issues)

- Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI Test)

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

November 1, 2012

What Milgram’s Shock Experiments Really Mean

Replicating Milgram's shock experiments reveals not blind obedience but deep moral conflict

By Michael Shermer

In 2010 I worked on a Dateline NBC television special replicating classic psychology experiments, one of which was Stanley Milgram's famous shock experiments from the 1960s. We followed Milgram's protocols precisely: subjects read a list of paired words to a “learner” (an actor named Tyler), then presented the first word of each pair again. Each time Tyler gave an incorrect matched word, our subjects were instructed by an authority figure (an actor named Jeremy) to deliver an electric shock from a box with toggle switches that ranged in 15-volt increments up to 450 volts (no shocks were actually delivered). In Milgram's original experiments, 65 percent of subjects went all the way to the end. We had only two days to film this segment of the show (you can see all our experiments at http://tinyurl.com/3yg2v29 ), so there was time for just six subjects, who thought they were auditioning for a new reality show called What a Pain!

Contrary to Milgram's conclusion that people blindly obey authorities to the point of committing evil deeds because we are so susceptible to environmental conditions, I saw in our subjects a great behavioral reluctance and moral disquietude every step of the way. Our first subject, Emily, quit the moment she was told the protocol. “This isn't really my thing,” she said with a nervous laugh. When our second subject, Julie, got to 75 volts and heard Tyler groan, she protested: “I don't think I want to keep doing this.” Jeremy insisted: “You really have no other choice. I need you to continue until the end of the test.” Despite our actor's stone-cold authoritative commands, Julie held her moral ground: “No. I'm sorry. I can just see where this is going, and I just—I don't—I think I'm good. I think I'm good to go.” When the show's host Chris Hansen asked what was going through her mind, Julie offered this moral insight on the resistance to authority: “I didn't want to hurt Tyler. And then I just wanted to get out. And I'm mad that I let it even go five [wrong answers]. I'm sorry, Tyler.”

Our third subject, Lateefah, became visibly upset at 120 volts and squirmed uncomfortably to 180 volts. When Tyler screamed, “Ah! Ah! Get me out of here! I refuse to go on! Let me out!” Lateefah made this moral plea to Jeremy: “I know I'm not the one feeling the pain, but I hear him screaming and asking to get out, and it's almost like my instinct and gut is like, ‘Stop,’ because you're hurting somebody and you don't even know why you're hurting them outside of the fact that it's for a TV show.” Jeremy icily commanded her to “please continue.” As she moved into the 300-volt range, Lateefah was noticeably shaken, so Hansen stepped in to stop the experiment, asking, “What was it about Jeremy that convinced you that you should keep going here?” Lateefah gave us this glance into the psychology of obedience: “I didn't know what was going to happen to me if I stopped. He just—he had no emotion. I was afraid of him.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Our fourth subject, a man named Aranit, unflinchingly cruised through the first set of toggle switches, pausing at 180 volts to apologize to Tyler—“I'm going to hurt you, and I'm really sorry”—then later cajoling him, “Come on. You can do this…. We are almost through.” After completing the experiment, Hansen asked him: “Did it bother you to shock him?” Aranit admitted, “Oh, yeah, it did. Actually it did. And especially when he wasn't answering anymore.” When asked what was going through his mind, Aranit turned to our authority, explicating the psychological principle of diffusion of responsibility: “I had Jeremy here telling me to keep going. I was like, ‘Well, should be everything's all right….’ So let's say that I left all the responsibilities up to him and not to me.”

Human moral nature includes a propensity to be empathetic, kind and good to our fellow kin and group members, plus an inclination to be xenophobic, cruel and evil to tribal others. The shock experiments reveal not blind obedience but conflicting moral tendencies that lie deep within.

SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ONLINE Comment on this article at ScientificAmerican.com/nov2012

Rethinking One of Psychology's Most Infamous Experiments

In the 1960s, Stanley Milgram's electric-shock studies showed that people will obey even the most abhorrent of orders. But recently, researchers have begun to question his conclusions — and offer some of their own.

In 1961, Yale University psychology professor Stanley Milgram placed an advertisement in the New Haven Register . “We will pay you $4 for one hour of your time,” it read, asking for “500 New Haven men to help us complete a scientific study of memory and learning.”

Only part of that was true. Over the next two years, hundreds of people showed up at Milgram’s lab for a learning and memory study that quickly turned into something else entirely. Under the watch of the experimenter, the volunteer—dubbed “the teacher”—would read out strings of words to his partner, “the learner,” who was hooked up to an electric-shock machine in the other room. Each time the learner made a mistake in repeating the words, the teacher was to deliver a shock of increasing intensity, starting at 15 volts (labeled “slight shock” on the machine) and going all the way up to 450 volts (“Danger: severe shock”). Some people, horrified at what they were being asked to do, stopped the experiment early, defying their supervisor’s urging to go on; others continued up to 450 volts, even as the learner pled for mercy, yelled a warning about his heart condition—and then fell alarmingly silent. In the most well-known variation of the experiment, a full 65 percent of people went all the way.

Until they emerged from the lab, the participants didn’t know that the shocks weren’t real, that the cries of pain were pre-recorded, and that the learner—railroad auditor Jim McDonough —was in on the whole thing, sitting alive and unharmed in the next room. They were also unaware that they had just been used to prove the claim that would soon make Milgram famous: that ordinary people, under the direction of an authority figure, would obey just about any order they were given, even to torture. It’s a phenomenon that’s been used to explain atrocities from the Holocaust to the Vietnam War’s My Lai massacre to the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. “To a remarkable degree,” Peter Baker wrote in Pacific Standard in 2013, “Milgram’s early research has come to serve as a kind of all-purpose lightning rod for discussions about the human heart of darkness.”

In some ways, though, Milgram’s study is also—as promised—a study of memory, if not the one he pretended it was.

More than five decades after it was first published in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology in 1963, it’s earned a place as one of the most famous experiments of the 20th century. Milgram’s research has spawned countless spinoff studies among psychologists, sociologists, and historians, even as it’s leapt from academia into the realm of pop culture. It’s inspired songs by Peter Gabriel (lyrics: “We do what we’re told/We do what we’re told/Told to do”) and Dar Williams (“When I knew it was wrong, I played it just like a game/I pressed the buzzer”); a number of books whose titles make puns out of the word “shocking”; a controversial French documentary disguised as a game show ; episodes of Law and Order and Bones ; a made-for-TV movie with William Shatner; a jewelry collection (bizarrely) from the company Enfants Perdus; and most recently, the biopic The Experimenter , starring Peter Sarsgaard as the title character—and this list is by no means exhaustive.

But as with human memory, the study—even published, archived, enshrined in psychology textbooks—is malleable. And in the past few years, a new wave of researchers have dedicated themselves to reshaping it, arguing that Milgram’s lessons on human obedience are, in fact, misremembered—that his work doesn’t prove what he claimed it does.

The problem is, no one can really agree on what it proves instead.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the experiments’ publication (or, technically, the 51st), the Journal of Social Issues released a themed edition in September 2014 dedicated to all things Milgram. “There is a compelling and timely case for reexamining Milgram’s legacy,” the editors wrote in the introduction, noting that they were in good company: In 1964, the year after the experiments were published, fewer than 10 published studies referenced Milgram’s work; in 2012, that number was more than 60.

It’s a trend that surely would have pleased Milgram, who crafted his work with an audience in mind from the beginning. “Milgram was a fantastic dramaturg. His studies are fantastic little pieces of theater. They’re beautifully scripted,” said Stephen Reicher, a professor of psychology at the University of St. Andrews and a co-editor of the Journal of Social Issues ’ special edition. Capitalizing on the fame his 1963 publication earned him, Milgram went on to publish a book on his experiments in 1974 and a documentary, Obedience , with footage from the original experiments.

But for a man determined to leave a lasting legacy, Milgram also made it remarkably easy for people to pick it apart. The Yale University archives contain boxes upon boxes of papers, videos, and audio recordings, an entire career carefully documented for posterity. Though Milgram’s widow Alexandra donated the materials after his death in 1984, they remained largely untouched for years, until Yale’s library staff began to digitize all the materials in the early 2000s. Able to easily access troves of material for the first time, the researchers came flocking.

“There’s a lot of dirty laundry in those archives,” said Arthur Miller, a professor emeritus of psychology at Miami University and another co-editor of the Journal of Social Issues . “Critics of Milgram seem to want to—and do—find material in these archives that makes Milgram look bad or unethical or, in some cases, a liar.”

One of the most vocal of those critics is Australian author and psychologist Gina Perry, who documented her experience tracking down Milgram’s research participants in her 2013 book Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments . Her project began as an effort to write about the experiments from the perspective of the participants—but when she went back through the archives to confirm some of their stories, she said, she found some glaring issues with Milgram’s data. Among her accusations: that the supervisors went off script in their prods to the teachers, that some of the volunteers were aware that the setup was a hoax, and that others weren’t debriefed on the whole thing until months later. “My main issue is that methodologically, there have been so many problems with Milgram’s research that we have to start re-examining the textbook descriptions of the research,” she said.

But many psychologists argue that even with methodological holes and moral lapses, the basic finding of Milgram’s work, the rate of obedience, still holds up. Because of the ethical challenge of reproducing the study, the idea survived for decades on a mix of good faith and partial replications—one study had participants administer their shocks in a virtual-reality system, for example—until 2007, when ABC collaborated with Santa Clara University psychologist Jerry Burger to replicate Milgram’s experiment for an episode of the TV show Basic Instincts titled “ The Science of Evil ,” pegged to Abu Ghraib.

Burger’s way around an ethical breach: In the most well-known experiment, he found, 80 percent of the participants who reached a 150-volt shock continued all the way to the end. “So what I said we could do is take people up to the 150-volt point, see how they reacted, and end the study right there,” he said. The rest of the setup was nearly identical to Milgram’s lab of the early 1960s (with one notable exception: “Milgram had a gray lab coat and I couldn’t find a gray, so I got a light blue.”)

At the end of the experiment, Burger was left with an obedience rate around the same as the one Milgram had recorded—proving, he said, not only that Milgram’s numbers had been accurate, but that his work was as relevant as ever. “[The results] didn’t surprise me,” he said, “but for years I had heard from my students and from other people, ‘Well, that was back in the 60s, and somehow how we’re more aware of the problems of blind obedience, and people have changed.’”

In recent years, though, much of the attention has focused less on supporting or discrediting Milgram’s statistics, and more on rethinking his conclusions. With a paper published earlier this month in the British Journal of Social Psychology , Matthew Hollander, a sociology Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin, is among the most recent to question Milgram’s notion of obedience. After analyzing the conversation patterns from audio recordings of 117 study participants, Hollander found that Milgram’s original classification of his subjects—either obedient or disobedient—failed to capture the true dynamics of the situation. Rather, he argued, people in both categories tried several different forms of protest—those who successfully ended the experiment early were simply better at resisting than the ones that continued shocking.

“Research subjects may say things like ‘I can’t do this anymore’ or ‘I’m not going to do this anymore,’” he said, even those who went all the way to 450 volts. “I understand those practices to be a way of trying to stop the experiment in a relatively aggressive, direct, and explicit way.”

It’s a far cry from Milgram’s idea that the capacity for evil lies dormant in everyone, ready to be awakened with the right set of circumstances. The ability to disobey toxic orders, Hollander said, is a skill that can be taught like any other—all a person needs to learn is what to say and how to say it.

In some ways, the conclusions Milgram drew were as much a product of their time as they were a product of his research. At the time he began his studies, the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the major architects of the Holocaust, was already in full swing. In 1963, the same year that Milgram published his studies, writer Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe Eichmann in her book on the trial, Eichmann in Jerusalem .

Milgram, who was born in New York City in 1933 to Jewish immigrant parents, came to view his studies as a validation of Arendt’s idea—but the Holocaust had been at the forefront of his mind for years before either of them published their work. “I should have been born into the German-speaking Jewish community of Prague in 1922 and died in a gas chamber some 20 years later,” he wrote in a letter to a friend in 1958. “How I came to be born in the Bronx Hospital, I’ll never quite understand.”

And in the introduction of his 1963 paper, he invoked the Nazis within the first few paragraphs: “Obedience, as a determinant of behavior, is of particular relevance to our time,” he wrote. “Gas chambers were built, death camps were guarded; daily quotas of corpses were produced … These inhumane policies may have originated in the mind of a single person, but they could only be carried out on a massive scale if a very large number of persons obeyed orders.”

Though the term didn’t exist at the time, Milgram was a proponent of what today’s social psychologists call situationism: the idea that people’s behavior is determined largely by what’s happening around them. “They’re not psychopaths, and they’re not hostile, and they’re not aggressive or deranged. They’re just people, like you and me,” Miller said. “If you put us in certain situations, we’re more likely to be racist or sexist, or we may lie, or we may cheat. There are studies that show this, thousands and thousands of studies that document the many unsavory aspects of most people.”

But continued to its logical extreme, situationism “has an exonerating effect,” he said. “In the minds of a lot of people, it tends to excuse the bad behavior … it’s not the person’s fault for doing the bad thing, it’s the situation they were put in.” Milgram’s studies were famous because their implications were also devastating: If the Nazis were just following orders, then he had proved that anyone at all could be a Nazi. If the guards at Abu Ghraib were just following orders, then anyone was capable of torture.

The latter, Reicher said, is part of why interest in Milgram’s work has seen a resurgence in recent years. “If you look at acts of human atrocity, they’ve hardly diminished over time,” he said, and news of the abuse at Abu Ghraib was surfacing around the same time that Yale’s archival material was digitized, a perfect storm of encouragement for scholars to turn their attention once again to the question of what causes evil.

He and his colleague Alex Haslam, the third co-editor of The Journal of Social Issues ’ Milgram edition and a professor of psychology at the University of Queensland, have come up with a different answer. “The notion that we somehow automatically obey authority, that we are somehow programmed, doesn’t account for the variability [in rates of obedience] across conditions,” he said; in some iterations of Milgram’s study, the rate of compliance was close to 100 percent, while in others it was closer to zero. “We need an account that can explain the variability—when we obey, when we don’t.”

“We argue that the answer to that question is a matter of identification,” he continued. “Do they identify more with the cause of science, and listen to the experimenter as a legitimate representative of science, or do they identify more with the learner as an ordinary person? … You’re torn between these different voices. Who do you listen to?”

The question, he conceded, applies as much to the study of Milgram today as it does to what went on in his lab. “Trying to get a consensus among academics is like herding cats,” Reicher said, but “if there is a consensus, it’s that we need a new explanation. I think nearly everybody accepts the fact that Milgram discovered a remarkable phenomenon, but he didn’t provide a very compelling explanation of that phenomenon.”

What he provided instead was a difficult and deeply uncomfortable set of questions—and his research, flawed as it is, endures not because it clarifies the causes of human atrocities, but because it confuses more than it answers.

Or, as Miller put it: “The whole thing exists in terms of its controversy, how it’s excited some and infuriated others. People have tried to knock it down, and it always comes up standing.”

About the Author

More Stories

The Definitive April Fool's Prank Bracket

The State Department Is Spring Breaking, Badly

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 18 February 2016

Modern Milgram experiment sheds light on power of authority

- Alison Abbott

Nature volume 530 , pages 394–395 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

2 Citations

417 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

People obeying commands feel less responsibility for their actions.

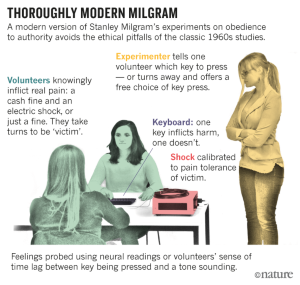

More than 50 years after a controversial psychologist shocked the world with studies that revealed people’s willingness to harm others on order, a team of cognitive scientists has carried out an updated version of the iconic ‘Milgram experiments’.

Their findings may offer some explanation for Stanley Milgram's uncomfortable revelations: when following commands, they say, people genuinely feel less responsibility for their actions — whether they are told to do something evil or benign.