Advertisement

Social Media Addiction and Its Impact on College Students' Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Stress

- Regular Article

- Published: 01 November 2021

- Volume 32 , pages 81–90, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Lei Zhao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7337-3065 1 , 2

8089 Accesses

20 Citations

1 Altmetric

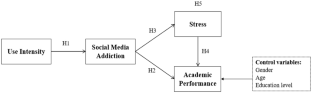

Explore all metrics

Social media use can bring negative effects to college students, such as social media addiction (SMA) and decline in academic performance. SMA may increase the perceived stress level of college students, and stress has a negative impact on academic performance, but this potential mediating role of stress has not been verified in existing studies. In this paper, a research model was developed to investigate the antecedent variables of SMA, and the relationship between SMA, stress and academic performance. With the data of 372 Chinese college students (mean age 21.3, 42.5% males), Partial Least Squares, Structural Equation Model was adopted to evaluate measurement model and structural model. The results show that use intensity is an important predictor of SMA, and both SMA and stress have a negative impact on college students’ academic performance. In addition, we further confirmed that stress plays a mediating role in the relationship between SMA and college students’ academic performance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

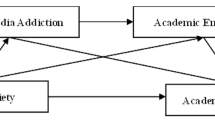

Social media addiction and academic engagement as serial mediators between social anxiety and academic performance among college students

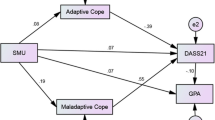

Psychological distress, social media use, and academic performance of medical students: the mediating role of coping style

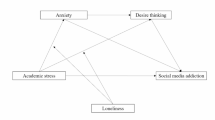

From academia to addiction: understanding the mechanism behind how academic stress fuels social media addiction in PhD students

Al-Yafi, K., El-Masri, M., & Tsai, R. (2018). The effects of using social network sites on academic performance: The case of Qatar. Journal of Enterprise Information Management , 31 (3), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-08-2017-0118 .

Andreassen, C. S., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Social network site addiction—an overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20 , 1–9.

Article Google Scholar

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64 , 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110 (2), 501–517.

Argyris, Y. E., & Xu, J. (2016). Enhancing self-efficacy for career development in Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 55 (2), 921–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.023

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55 (5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.023

Bano, S., Cisheng, W., Khan, A., & Khan, N. A. (2019). WhatsApp use and student’s psychological well-being: Role of social capital and social integration. Children and Youth Services Review, 103 , 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.06.002

Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2 (2), 285–309.

Google Scholar

Bijari, B., Javadinia, S. A., Erfanian, M., Abedini, M. R., & Abassi, A. (2013). The impact of virtual social networks on students’ academic achievement in Birjand University of Medical Sciences in East Iran. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 83 , 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.020

Błachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., & Pantic, I. (2016). Association between facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Computers in Human Behavior, 55 , 701–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.026

Brailovskaia, J., Rohmann, E., Bierhoff, H. W., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2019). The relationship between daily stress, social support and Facebook addiction disorder. Psychiatry Research, 276 , 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.014

Brailovskaia, J., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2018). Facebook addiction disorder in Germany. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21 (7), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0140

Buil, I., Martínez, E., & Matute, J. (2016). From internal brand management to organizational citizenship behaviors: Evidence from frontline employees in the hotel industry. Tourism Management, 57 (12), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.009

Busalim, A. H., Masrom, M., & Zakaria, W. N. B. W. (2019). The impact of Facebook addiction and self-esteem on students’ academic performance: A multi-group analysis. Computers & Education, 142 , 103651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103651

Carolus, A., Binder, J. F., Muench, R., Schmidt, C., Schneider, F., & Buglass, S. L. (2019). Smartphones as digital companions: Characterizing the relationship between users and their phones. New Media & Society, 21 , 914–938. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818817074

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2020. The 44th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China (in Chinese). Retrieved August 28, 2020, from http://www.cac.gov.cn/2020-08/30/c_1124938750.htm

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24 (4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Dendle, C., Baulch, J., Pellicano, R., Hay, M., Lichtwark, I., Ayoub, S., & Horne, K. (2018). Medical student psychological distress and academic performance. Medical Teacher . https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2018.99099

Doleck, T., & Lajoie, S. (2018). Social networking and academic performance: A review. Education and Information Technologies, 23 (1), 435–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9612-3

Griffths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addictions: An overview of preliminary findings. Behavioral Addictions Criteria, Evidence, and Treatment , 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9 .

Hair, J. F. J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) . Sage Publication.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of pls-sem. European Business Review, 31 (1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76 (4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

Hormes, J. M., Kearns, B., & Timko, C. A. (2014). Craving Facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction, 109 (12), 2079–2088. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12713

Hsiao, K. L., Shu, Y., & Huang, T. C. (2017). Exploring the effect of compulsive social app usage on technostress and academic performance: Perspectives from personality traits. Telematics and Informatics, 34 , 679–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.11.001

Jie, T., Yizhen, Y., Yukai, D., Ying, M., Dongying, Z., & Jiaji, W. (2014). Addictive behaviors prevalence of internet addiction and its association with stressful life events and psychological symptoms among adolescent internet users. Addictive Behaviors, 39 (3), 744–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.07.012

Juana, I., Serafín, B., Jesús, L., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of music therapy and progressive muscle relaxation in reducing stress before exams and improving academic performance in nursing students: A randomized trial. Nurse Education Today, 84 , 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104217

Kimberly, Y. (2009). Facebook addiction disorder . The Center for Online Addiction.

Lau, W. W. F. (2017). Effects of social media usage and social media multitasking on the academic performance of university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 68 (3), 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.043

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping . Springer.

Lee, W. W. S. (2017). Relationships among grit, academic performance, perceived academic failure, and stress in associate degree students. Journal of Adolescence, 60 , 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.006

Leung, L. (2007). Stressful life events, motives for Internet use, and social support among digital kids. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10 (2), 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9967

Liang, C., Gu, D., Tao, F., Jain, H. K., Zhao, Y., & Ding, B. (2017). Influence of mechanism of patient-accessible hospital information system implementation on doctor-patient relationships: A service fairness perspective. Information & Management, 54 (1), 57–72.

Lim, K., & Jeoung, Y. S. (2010). Understanding major factors in taking Internet based lectures for the national college entrance exam according to academic performance by case studies. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 10 (12), 477–491. https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2010.10.12.477

Lim, Y., & Nam, S.-J. (2016). Time spent on the Internet by multicultural adolescents in Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 37 (1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2016.1169994

Lin, C. L., Jin, Y. Q., Zhao, Q., Yu, S. W., & Su, Y. S. (2021). Factors influence students’ switching behavior to online learning under covid-19 pandemic: A push-pull-mooring model perspective. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30 (3), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00570-0

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33 (3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.004

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 83 , 262–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009

Masood, A., Luqman, A., Feng, Y., & Ali, A. (2020). Adverse consequences of excessive social networking site use on academic performance: Explaining underlying mechanism from stress perspective. Computers in Human Behavior . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106476

McDaniel, B. (2015). ‘Technoference’: Everyday intrusions and inter-ruptions of technology in couple and family relationships. In C. Bruess Içinde (Ed.), Family communication in the age of digital and social media. Peter Lang Publishing.

Nayak, J. K. (2018). Relationship among smartphone usage, addiction, academic performance and the moderating role of gender: A study of higher education students in India. Computers and Education, 123 (5), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.007

O'Brien, L. (2012). Six ways to use social media in education. Retrieved from https://cit.duke.edu/blog/2012/04/six-ways-to-use-social-media-in-education/

Orosz, G., Istvan, T., & Beata, B. (2016). Four facets of Facebook intensity—the development of the multidimensional facebook intensity scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 100 , 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.038

Oye, N. D., Adam, M. H., & Nor Zairah, A. R. (2012). Model of perceived influence of academic performance using social networking. International Journal of Computers and Technology, 2 (2), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.24297/ijct.v2i1.2612

Pang, H. (2018). How does time spent on WeChat bolster subjective well-being through social integration and social capital? Telematics and Informatics, 25 , 2147–2156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.07.015

Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2117–2127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.016

Peng, Y., & Li, J. (2021). The effect of customer education on service innovation satisfaction: The mediating role of customer participation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47 (5), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.12.014

Phu, B., & Gow, A. J. (2019). Facebook use and its association with subjective happiness and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 92 , 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.020

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology , 88 (5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 .

Prato, C. A., & Yucha, C. B. (2013). Biofeedback-assisted relaxation training to decrease test anxiety in nursing students. Nursing Education Perspectives, 34 (2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/00024776-201303000-00003

Rouis, S. (2012). Impact of cognitive absorption on facebook on students’ achievement. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15 (6), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0390

Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., & Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of facebook: A review of facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3 (3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016

Sandra, K., Dawans, B. V., Heinrichs, M., & Fuchs, R. (2013). Does the level of physical exercise affect physiological and psychological responses to psychosocial stress in women. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14 , 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.11.003

Shaw, M., & Black, D. W. (2008). Internet addiction . Springer.

Shi, C., Yu, L., Wang, N., Cheng, B., & Cao, X. (2020). Effects of social media overload on academic performance: A stressor–strain–outcome perspective. Asian Journal of Communication, 30 (2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2020.1748073

Statista (2020). Number of social media users worldwide from 2010 to 2021 (in billions). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/

Tang, J. H., Chen, M. C., Yang, C. Y., Chung, T. Y., & Lee, Y. A. (2016). Personality traits, interpersonal relationships, online social support, and Facebook addiction. Telematics and Informatics, 33 (1), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.06.003

Wang, J. L., Wang, H. Z., Gaskin, J., & Wang, L. H. (2015). The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 53 , 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.005

Wartberg, L., Kriston, L., & Thomasius, R. (2020). Internet gaming disorder and problematic social media use in a representative sample of German adolescents: Prevalence estimates, comorbid depressive symptoms and related psychosocial aspects. Computers in Human Behavior, 103 , 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.014

Xu, X. A., Xue, K. N., Wang, L. L., Gursoy, D., & Song, Z. B. (2021). Effects of customer-to-customer social interactions in virtual travel communities on brand attachment: the mediating role of social well-being. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38 , 100790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100790

Zhao, L. (2021). The impact of social media use types and social media addiction on subjective well-being of college students: A comparative analysis of addicted and non-addicted students. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4 (2), 100122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100122

Zhao, L., Liang, C., & Gu, D. (2021). Mobile social media use and trailing parents’ life satisfaction: Social capital and social integration perspective. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 92 (3), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020905549

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Planning Subject for the 14th Five-year Plan of National Education Sciences (Grant No. EIA210425).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Management, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, 230009, Anhui, China

Wendian College, Anhui University, Hefei, 230601, Anhui, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lei Zhao .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Zhao, L. Social Media Addiction and Its Impact on College Students' Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Stress. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 32 , 81–90 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00635-0

Download citation

Accepted : 21 October 2021

Published : 01 November 2021

Issue Date : February 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00635-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Use intensity

- Social media addiction

- Academic performance

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 33268185

- DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

With the increasing use of social media, the addictive use of this new technology also grows. Previous studies found that addictive social media use is associated with negative consequences such as reduced productivity, unhealthy social relationships, and reduced life-satisfaction. However, a holistic theoretical understanding of how social media addiction develops is still lacking, which impedes practical research that aims at designing educational and other intervention programs to prevent social media addiction. In this study, we reviewed 25 distinct theories/models that guided the research design of 55 empirical studies of social media addiction to identify theoretical perspectives and constructs that have been examined to explain the development of social media addiction. Limitations of the existing theoretical frameworks were identified, and future research areas are proposed.

Keywords: Facebook addiction; Internet addiction; Literature review; Problematic use; Social media addiction; Theoretical framework.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Scaling Up Research on Drug Abuse and Addiction Through Social Media Big Data. Kim SJ, Marsch LA, Hancock JT, Das AK. Kim SJ, et al. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Oct 31;19(10):e353. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6426. J Med Internet Res. 2017. PMID: 29089287 Free PMC article.

- Predictors of Problematic Social Media Use: Personality and Life-Position Indicators. Sheldon P, Antony MG, Sykes B. Sheldon P, et al. Psychol Rep. 2021 Jun;124(3):1110-1133. doi: 10.1177/0033294120934706. Epub 2020 Jun 24. Psychol Rep. 2021. PMID: 32580682

- Empirical Relationships between Problematic Alcohol Use and a Problematic Use of Video Games, Social Media and the Internet and Their Associations to Mental Health in Adolescence. Wartberg L, Kammerl R. Wartberg L, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Aug 21;17(17):6098. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176098. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. PMID: 32825700 Free PMC article.

- The "Vicious Circle of addictive Social Media Use and Mental Health" Model. Brailovskaia J. Brailovskaia J. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024 Jul;247:104306. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104306. Epub 2024 May 11. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024. PMID: 38735249 Review.

- Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Cheng C, Lau YC, Chan L, Luk JW. Cheng C, et al. Addict Behav. 2021 Jun;117:106845. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106845. Epub 2021 Jan 26. Addict Behav. 2021. PMID: 33550200 Review.

- Distal and proximal factors of wearable users' quantified-self dependence: A cognitive-behavioral model. Liu J, Chen S. Liu J, et al. Digit Health. 2024 Sep 26;10:20552076241286560. doi: 10.1177/20552076241286560. eCollection 2024 Jan-Dec. Digit Health. 2024. PMID: 39360241 Free PMC article.

- Bidirectional associations between sleep and anxiety among Chinese schoolchildren before and after the COVID-19 lockdown. Wang Z, Hong B, Su Y, Li M, Zou K, Wang L, Zhao L, Jia P, Song G. Wang Z, et al. Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 18;14(1):21807. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-72461-5. Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 39294217 Free PMC article.

- Social Media Use, Emotional Investment, Self-Control Failure, and Addiction in Relation to Mental and Sleep Health in Hispanic University Emerging Adults. Garcia MA, Cooper TV. Garcia MA, et al. Psychiatr Q. 2024 Aug 22. doi: 10.1007/s11126-024-10085-8. Online ahead of print. Psychiatr Q. 2024. PMID: 39172319

- Scrolling for fun or to cope? Associations between social media motives and social media disorder symptoms in adolescents and young adults. Thorell LB, Autenrieth M, Riccardi A, Burén J, Nutley SB. Thorell LB, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Aug 2;15:1437109. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1437109. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 39156819 Free PMC article.

- The enduring echoes of juvenile bullying: the role of self-esteem and loneliness in the relationship between bullying and social media addiction across generations X, Y, Z. Lissitsa S, Kagan M. Lissitsa S, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Aug 2;15:1446000. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1446000. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 39156810 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- ClinicalKey

- Elsevier Science

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Social Media Addiction and its Effects to Senior High School Students' Behavior in School A Research Study

Related papers

Enough (or maybe not so much) has been said about social media and its adverse consequences on humans, particularly the young ones. Yet, the concept is inexhaustible, it remains elusive as we are in a constant flux from one existing social platform to a new and more advanced, sophisticated social platform. Our aim, therefore is to look critically into the adverse effects of excessive use of social media on our growing teens especially in our contemporary era. The question is not whether social media is good or bad but how much good can be derived from it and how much efforts we are putting to curb the bad, negative effects of social media. To begin, what does it mean to be social? What is media? To be social means relating to society or its organization, to interact, mingle and contribute to the betterment of such society or community as the case may be. Media, on the other hand, are the communication outlets or tools used to store and deliver information or data. Thus, when we put these two words together, we have what is called social media. What is worthy of note in this exercise is that social media go beyond the popular Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and the likes. What then is social media? What is social media? According to Investopedia, an online resource, "social media is a computer-based technology that facilitates the sharing of ideas, thoughts, and information through the building of virtual networks and communities." By design, social media is Internet-based and gives users quick electronic communication of content. Content includes personal information, documents, videos, and photos. Users engage with social media via a computer, tablet, or smartphone via web-based software or applications.

The Island - Sunday News Paper, 2018

Social media is an internet medium through which people or communities connect. Common reasons for social networking are building and maintaining relationships, expressing beliefs and ideas, sharing information, or even combating boredom. Communication can be conducted by communities or groups interacting and sharing information. The most commonly used global social networking sites are Facebook, Twitter, Myspace, and LinkedIn. They have become increasingly popular, and social media has become a vital daily routine for most teenagers. most renowned social network, Facebook, launched in 2004; it currently has over one billion active users and is still growing.

Social media has become an increasingly important part of all cultures around the World. Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Multiply and other social media sites have swept the nation and have come to dominate the millennial generation way of thinking and behaving. Social media allows interactive dialogue and social interaction with many people who in this day spend a lot of great deal online such as working, leisure, entertaining, and so on. Many cannot deny that using internet is helped to find the great deal of information and spend less time to do so. Until today there are still surprisingly few studies conducted on the subject matter of symptoms of Internet addiction and what can and cannot be classified as such, making this so called pathological sickness debatable. Many claimed that social media is merely a channel or medium that leads to other addictions. Therefore, many researchers have been working on the benefit of using internet. However, in this study the researcher searched ...

Social media's impact on youth is creating additional challenges and opportunities. Social Networking sites provide a platform for discussion on burning issues that has been overlooked in today's scenario. The impact of social networking sites in the changing mind-set of the youth. It was survey type research and data was collected through the questionnaire. 300 sampled youth fill the questionnaire; non-random sampling technique was applied to select sample units. The main objectives were as (1) To analyze the influence of social media on youth social life (2) To assess the beneficial and preferred form of social media for youth (3) To evaluate the attitude of youth towards social media and measure the spending time on social media (4) To recommend some measure for proper use of social media in right direction to inform and educate the people. Collected data was analyzed in term of frequency, percentage, and mean score of statements. Following were main findings Majority of the respondents shows the agreements with these influences of social media. Respondents opine Facebook as their favorite social media form, and then the like Skype as second popular form of social media, the primary place for them, 46 percent responded connect social media in educational institution computer labs, mainstream responded as informative links share, respondents Face main problem during use of social are unwanted messages, social media is beneficial for youth in the field of education, social media deteriorating social norms, social media is affecting negatively on study of youth. Social media promotes unethical pictures, video clips and images among youth, anti-religious post and links create hatred among peoples of different communities, Negative use of social media is deteriorating the relationship among the countries, social media is playing a key role to create political awareness among youth. Introduction Social media is most recent form of media and having many features and characteristics. It have many facilities on same channel like as communicating ,texting, images sharing , audio and video sharing , fast publishing, linking with all over world, direct connecting. it is also cheapest fast access to the world so it is very important for all age of peoples. Its use is increasing day by day with high rate in all over the

Journal of Education Technology in Health Sciences, 2023

Abstract Utilizing the technology made our life very easier and brought the globe in our hand which has got both pros and cons. Young generation is more of techno oriented than the values that makes them to be depending on the social medias easily that affects the domains of health. A study was conducted to assess the Social media addiction among the paramedical students. Quantitative research approach with non experimental, descriptive research design was used. Non probability convenient sampling technique was used to select 140 para medical students who fulfills the inclusion criteria. Self administered structured questionnaire was used. Modified social media addiction likert scale was used with 20 items. Findings of the study shows that vast majority (103(74%)) of the students were addicted to the social media. To conclude, it is the high time for the policy-makers to restrict on this and make provision to improve the interaction skills. Keywords: Social media addiction, Social interactions.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine, 2020

Research Journey, 2019

Science Insights, 2017

Journal of information and communication convergence engineering, 2014

IRJET, 2021

isara solutions, 2023

www.ijiemr.org, 2023

International Journal of All Research Education & Scientific Methods

AJIT-e: Online Academic Journal of Information Technology, 2019

Journal of Medical Science And clinical Research, 2018

International Journal of E-Business Research

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research), 2022

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Learning Tips

- Exam Guides

- School Life

Thesis Statements about Social Media: 21 Examples and Tips

- by Judy Jeni

- January 27, 2024

A thesis statement is a sentence in the introduction paragraph of an essay that captures the purpose of the essay. Using thesis statements about social media as an example, I will guide you on how to write them well.

It can appear anywhere in the first paragraph of the essay but it is mostly preferred when it ends the introduction paragraph. learning how to write a thesis statement for your essay will keep you focused.

A thesis statement can be more than one sentence only when the essay is on complex topics and there is a need to break the statement into two. This means, a good thesis statement structures an essay and tells the reader what an essay is all about.

A good social media thesis statement should be about a specific aspect of social media and not just a broad view of the topic.

The statement should be on the last sentence of the first paragraph and should tell the reader about your stand on the social media issue you are presenting or arguing in the essay.

Reading an essay without a thesis statement is like solving a puzzle. Readers will have to read the conclusion to at least grasp what the essay is all about. It is therefore advisable to craft a thesis immediately after researching an essay.

Throughout your entire writing, every point in every paragraph should connect to the thesis. In case it doesn’t then probably you have diverged from the main issue of the essay.

How to Write a Thesis Statement?

Writing a thesis statement is important when writing an essay on any topic, not just about social media. It is the key to holding your ideas and arguments together into just one sentence.

The following are tips on how to write a good thesis statement:

Start With a Question and Develop an Answer

If the question is not provided, come up with your own. Start by deciding the topic and what you would like to find out about it.

Secondly, after doing some initial research on the topic find the answers to the topic that will help and guide the process of researching and writing.

Consequently, if you write a thesis statement that does not provide information about your research topic, you need to construct it again.

Be Specific

The main idea of your essay should be specific. Therefore, the thesis statement of your essay should not be vague. When your thesis statement is too general, the essay will try to incorporate a lot of ideas that can contribute to the loss of focus on the main ideas.

Similarly, specific and narrow thesis statements help concentrate your focus on evidence that supports your essay. In like manner, a specific thesis statement tells the reader directly what to expect in the essay.

Make the Argument Clear

Usually, essays with less than one thousand words require the statement to be clearer. Remember, the length of a thesis statement should be a single sentence, which calls for clarity.

In these short essays, you do not have the freedom to write long paragraphs that provide more information on the topic of the essay.

Likewise, multiple arguments are not accommodated. This is why the thesis statement needs to be clear to inform the reader of what your essay is all about.

If you proofread your essay and notice that the thesis statement is contrary to the points you have focused on, then revise it and make sure that it incorporates the main idea of the essay. Alternatively, when the thesis statement is okay, you will have to rewrite the body of your essay.

Question your Assumptions

Before formulating a thesis statement, ask yourself the basis of the arguments presented in the thesis statement.

Assumptions are what your reader assumes to be true before accepting an argument. Before you start, it is important to be aware of the target audience of your essay.

Thinking about the ways your argument may not hold up to the people who do not subscribe to your viewpoint is crucial.

Alongside, revise the arguments that may not hold up with the people who do not subscribe to your viewpoint.

Take a Strong Stand

A thesis statement should put forward a unique perspective on what your essay is about. Avoid using observations as thesis statements.

In addition, true common facts should be avoided. Make sure that the stance you take can be supported with credible facts and valid reasons.

Equally, don’t provide a summary, make a valid argument. If the first response of the reader is “how” and “why” the thesis statement is too open-ended and not strong enough.

Make Your Thesis Statement Seen

The thesis statement should be what the reader reads at the end of the first paragraph before proceeding to the body of the essay. understanding how to write a thesis statement, leaves your objective summarized.

Positioning may sometimes vary depending on the length of the introduction that the essay requires. However, do not overthink the thesis statement. In addition, do not write it with a lot of clever twists.

Do not exaggerate the stage setting of your argument. Clever and exaggerated thesis statements are weak. Consequently, they are not clear and concise.

Good thesis statements should concentrate on one main idea. Mixing up ideas in a thesis statement makes it vague. Read on how to write an essay thesis as part of the steps to write good essays.

A reader may easily get confused about what the essay is all about if it focuses on a lot of ideas. When your ideas are related, the relation should come out more clearly.

21 Examples of Thesis Statements about Social Media

- Recently, social media is growing rapidly. Ironically, its use in remote areas has remained relatively low.

- Social media has revolutionized communication but it is evenly killing it by limiting face-to-face communication.

- Identically, social media has helped make work easier. However,at the same time it is promoting laziness and irresponsibility in society today.

- The widespread use of social media and its influence has increased desperation, anxiety, and pressure among young youths.

- Social media has made learning easier but its addiction can lead to bad grades among university students.

- As a matter of fact, social media is contributing to the downfall of mainstream media. Many advertisements and news are accessed on social media platforms today.

- Social media is a major promoter of immorality in society today with many platforms allowing sharing of inappropriate content.

- Significantly, social media promotes copycat syndrome that positively and negatively impacts the behavior adapted by different users.

- In this affluent era, social media has made life easy but consequently affects productivity and physical strength.

- The growth of social media and its ability to reach more people increases growth in today’s business world.

- The freedom on social media platforms is working against society with the recent increase in hate speech and racism.

- Lack of proper verification when signing up on social media platforms has increased the number of minors using social media exposing them to cyberbullying and inappropriate content.

- The freedom of posting anything on social media has landed many in trouble making the need to be cautious before posting anything important.

- The widespread use of social media has contributed to the rise of insecurity in urban centers

- Magazines and journals have spearheaded the appreciation of all body types but social media has increased the rate of body shaming in America.

- To stop abuse on Facebook and Twitter the owners of these social media platforms must track any abusive post and upload and ban the users from accessing the apps.

- Social media benefits marketing by creating brand recognition, increasing sales, and measuring success with analytics by tracking data.

- Social media connects people around the globe and fosters new relationships and the sharing of ideas that did not exist before its inception.

- The increased use of social media has led to the creation of business opportunities for people through social networking, particularly as social media influencers.

- Learning is convenient through social media as students can connect with education systems and learning groups that make learning convenient.

- With most people spending most of their free time glued to social media, quality time with family reduces leading to distance relationships and reduced love and closeness.

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Social Media — Social Media Addiction

Social Media Addiction

- Categories: Social Media

About this sample

Words: 538 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 538 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Causes of social media addiction, consequences of social media addiction, addressing social media addiction.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1438 words

5 pages / 2417 words

6 pages / 2596 words

4 pages / 1935 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Media

In conclusion, the impact of social media on mental health is multifaceted, encompassing both positive and negative aspects. It is essential for individuals to approach social media with critical awareness and conscious [...]

Anderson, C. A., & Jiang, S. (2018). The value of social media data. Marketing Science, 37(3), 387-402.Boczkowski, P. J., & Mitchelstein, E. (2013). The news gap: When the information preferences of the media and the public [...]

The rise of fake news in the era of social media has given rise to a complex and multifaceted challenge that society must grapple with. The rapid dissemination of misleading or fabricated information through online platforms has [...]

Clarke, Roger. 'Dataveillance by Governments: The Technique of Computer Matching.' In Information Systems and Dataveillance, edited by Roger Clarke and Richard Wright, 129-142. Sydney, Australia: Australian Computer Society, [...]

Social media creates a dopamine-driven feedback loop to condition young adults to stay online, stripping them of important social skills and further keeping them on social media, leading them to feel socially isolated. Annotated [...]

Ever since social media was introduced as such a necessary and almost vital part of our lives, several concerns have risen about the boundaries at which we must draw in terms of our privacy. The mass of information users pour [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay on Addiction Of Social Media

Students are often asked to write an essay on Addiction Of Social Media in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Addiction Of Social Media

Understanding social media addiction.

Social media addiction is when a person spends too much time on social media sites like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, etc. This can lead to problems like ignoring schoolwork, losing sleep, and even feeling unhappy. It’s like a bad habit that’s hard to break.

The Causes of Addiction

People often get addicted to social media because it makes them feel good. They like getting likes, comments, and shares. It can also be because they feel lonely or bored. Social media seems like an easy way to feel better or pass the time.

Effects of Social Media Addiction

Being addicted to social media can cause problems. It can lead to poor grades in school because of not studying. It can also cause lack of sleep, which can make you feel tired and grumpy. You might even stop spending time with friends and family.

Overcoming Social Media Addiction

Breaking free from social media addiction is not easy but possible. One can start by setting time limits for using social media. Also, finding other activities like sports or reading can help. Talking about the problem with someone you trust can also help.

250 Words Essay on Addiction Of Social Media

Signs of social media addiction.

There are several signs that you might be addicted to social media. You might check your accounts constantly, even when you’re supposed to be doing other things. You might also feel anxious or upset if you can’t use social media. You might even ignore real-life activities to spend more time online.

Addiction to social media can have serious effects. It can hurt your school grades because you’re not focusing on your work. It can also harm your relationships because you’re not spending time with people in person. In addition, it can lead to mental health issues like anxiety and depression.

Ways to Combat Social Media Addiction

There are ways to combat social media addiction. You can set limits on how much time you spend on social media each day. You can also turn off notifications so you’re not tempted to check constantly. It’s also important to spend time doing other things you enjoy, like reading, playing sports, or hanging out with friends in person.

In conclusion, social media addiction is a serious problem that can have harmful effects. But by recognizing the signs and taking steps to control your use, you can overcome this addiction. It’s all about balance – using social media in a healthy way while still enjoying real life.

500 Words Essay on Addiction Of Social Media

Introduction.

Social media has become a big part of our lives. We use it to chat with friends, share photos, and learn about the world. But sometimes, we spend too much time on it. This is called social media addiction.

What is Social Media Addiction?

The causes of social media addiction.

There are many reasons why people get addicted to social media. One reason is that it makes them feel good. When someone likes or comments on their post, it can make them feel happy and important. Another reason is that it can help them feel less lonely. If they are feeling sad or bored, they can go on social media and talk to their friends.

The Effects of Social Media Addiction

Social media addiction can have many bad effects. It can make a person feel anxious or depressed. They might worry a lot about what other people think of them. It can also make them feel lonely. Even though they are talking to people online, they are not spending time with people in real life. This can make them feel alone and sad.

How to Overcome Social Media Addiction

Overcoming social media addiction is not easy, but it is possible. The first step is to admit that there is a problem. The next step is to set limits. This means deciding how much time to spend on social media each day, and sticking to it. It can also help to find other activities to do, like reading a book or playing a sport.

Social media can be a fun and useful tool. But like anything else, it is important to use it in a balanced way. If we spend too much time on it, it can lead to problems like anxiety, depression, and poor grades. By setting limits and finding other activities to enjoy, we can avoid these problems and have a healthier relationship with social media.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychiatry

- v.65(5); 2023 May

- PMC10309264

Self-esteem and social media addiction level in adolescents: The mediating role of body image

Mehmet colak.

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Freelance Physician, Izmir, Turkey

Ozlem Sireli Bingol

1 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Freelance Physician, Mugla, Turkey

2 Department of Psychiatry, Beykent University Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

Background:

There are many studies examining the relationship between social media and self-esteem. Studies examining the relationships between the self-esteem, social media use, and body image of adolescents are limited in the literature.

This study aimed to examine the relationship between self-esteem and social media addiction levels in adolescents and the mediating role of body image in the relationship between these two variables.

The sample of the study consisted of 204 adolescents, 67 (32.8%) girls and 137 (67.2%) boys, with a mean age of 15.90 ± 1.20 years, who were high school students. The self-esteem levels of the participants were evaluated with the “Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale”, their social media dependency levels were measured with the “Social Media Use Disorder Scale”, and their body images were measured using the “Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire”.

No significant relationship was found between the self-esteem levels of the participants and their ages or the education levels of their parents. There was a negative moderate significant relationship between the self-esteem levels of the participants and their social media addiction levels, and a positive moderate significant correlation was found between their self-esteem levels and body images. It was found that the social media addiction levels of the participants negatively predicted their self-esteem and body image levels. It was determined that body image had a partial mediator effect on the relationship between the social media addiction and self-esteem levels of the participants.

Conclusion:

Our results revealed that there is a negative correlation between self-esteem and social media addiction levels in adolescents. Body image has a partial mediating role in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem levels.

INTRODUCTION

Self-esteem refers to feelings of love, respect, and trust that a person feels toward oneself as a result of knowing oneself and evaluating oneself realistically, accepting their abilities and strengths as they are and embracing oneself.[ 1 ] Self-esteem has a very important place in human life, especially in adolescence.[ 2 ]

Adolescents use their self-perception as a tool when seeking answers to developmental questions such as what they are like and how they feel about themselves. Self-image plays an important role in the way adolescents approach themselves, and therefore, in the formation of self-esteem.[ 2 ] There are many studies examining self-esteem and the factors affecting self-esteem in adolescent individuals.[ 3 ] Studies have found that many factors such as sociodemographic variables, family structure, parental attitudes, peer relationships, perceived social support levels, academic success, and physical and/or mental illness are associated with self-esteem in adolescents.[ 3 , 4 ] Social media is thought to affect self-esteem during adolescence.[ 5 ]

Social media is defined as a structure consisting of various technological activities in social interaction and content creation. In this structure, the individual introduces oneself to other individuals, either as they are or with another identity that they want to have and can interact with.[ 6 ] Social media provides convenience in terms of acquiring and sharing information. However, it can easily turn into addiction when used frequently and/or at an uncontrollable level.[ 7 ] Studies have shown that the group with the highest frequency of social media use is adolescents.[ 7 , 8 ] Many studies have demonstrated that the excessive use of social media negatively affects areas such as academic functionality, social relationships, mental health, life satisfaction, and self-esteem in adolescents.[ 9 , 10 ] Most research has indicated a negative relationship between social media use and self-esteem. Adolescents with low self-esteem have high levels of social media use.[ 11 , 12 ] Body image is another important factor that affects self-esteem in adolescents.[ 13 ]

Body image is defined as a person’s feelings and thoughts about their own body regarding how their physical appearance is evaluated by others.[ 14 ] Studies have shown a positive relationship between body image and self-esteem in adolescents and that self-esteem levels are high in adolescents with a highly positive body image.[ 13 , 15 ]

Aside from studies reporting that the excessive use of social media negatively affects self-esteem, there are also studies showing that social media has positive effects on adolescents.[ 16 , 17 ] The differences in the results of studies on the topic suggest that some mediator variables may play a role in the relationship between social media use and self-esteem in adolescents.

As per previous research, there is a relationship between self-esteem and body image in adolescents. However, studies examining the relationships between these two variables along with the variable of social media use seem to be limited.[ 18 , 19 ] This study aimed to investigate the relationship between self-esteem and social media use in adolescents and the mediating role of body image in this relationship. The literature review that was conducted for this study revealed no previous study examining the mediating role of body image in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem levels. It is thought that the results of this study will contribute to the literature on this topic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at a public high school in the Bodrum district of Mugla in the academic year of 2020-2021. Participants were randomly selected from students studying in the first, second, third, and fourth years of high school education. The minimum required sample size was calculated with G*Power (3.1.9.4) against a nominal significance level of α = 0.5 and power values of 1-β = 0.8 and 1-β = 0.9. As per the results of the analysis, the number of participants to be included was determined as 204. Students aged 14-18 years who voluntarily agreed to participate were included in the study.

Sociodemographic Data Form: The form that was prepared by the researchers included questions on demographic information such as the age, gender, grade level, parental age, and parental education levels of the participants.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES): The scale was developed by Morris Rosenberg (1965). The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was performed by Cuhadaroglu.[ 1 ] The scale consists of 63 items and 12 subtests. In this study, only the self-esteem subtest was used. In the test, which was arranged as per the Guttman measurement method, positively and negatively worded items were ordered consecutively. As per the self-assessment system of the scale, the responded obtains a score between 0 and 6. In comparisons made with numerical measurements, self-esteem is evaluated as high (0-1 points), moderate (2-4 points), or low (5-6 points). A high total score of the scale indicates low self-esteem and a low total score indicates high self-esteem. The validity coefficient of the scale was found to be 0.71 and its reliability coefficient was 0.75 in its Turkish adaptation studies.

Social Media Use Disorder Scale (SMD-9): The scale was developed to measure the social media addiction levels of adolescents by Van den Eijnden, Lemmens, and Valkenburg (2016). The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Saricam.[ 20 ] SMD consists of two separate forms, a short form with 9 items and a long form with 27 items. While preparing the items, the criteria in the Pathological Gambling Addiction title in DSM-IV and Internet Gambling Disorders in DSM-5 were taken as the basis, and a total of nine criteria (occupation, endurance, withdrawal, insistence, escape, problems, cheating, displacement, and conflict) were used. An item pool was created. There is one item for each criterion in the nine-item short form. The scale has an 8-point rating between “0 = never” and “7 = more than 40 times a day”. The total score of the scale ranges between 0 and 63. The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was reported as 0.75 and its Guttman split half test reliability coefficient was found as 0.64. The corrected item total correlation coefficients ranged from 0.29 to 0.73 in the Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale.

Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ): This scale was developed by Winstead and Cash (1984) to determine the attitudes of individuals about their body image. MBSRQ is a 5-point Likert-type scale consisting of 57 items. The scale consists of seven dimensions. These dimensions are “physical appearance evaluation”, “appearance orientation”, “physical ability evaluation”, “physical adequacy orientation”, “health evaluation”, “health orientation”, and “satisfaction with body areas”. The minimum and maximum total scores of the scale are 57 and 285, respectively. A high total score indicates a positive body image, while a low score indicates a negative body image. The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was performed by Dogan and Dogan.[ 21 ] The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was reported as 0.94, and the internal consistency coefficients of the dimensions ranged between 0.75 and 0.91 in the Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale.

Ethics Committee approval for the study was received from Beykent University Publication Ethics Committee (July 24, 2020). The necessary permissions were obtained from the Provincial Directorate of National Education (November 17, 2020). The scales, which were converted into an online questionnaire by the researchers, were delivered to the students via e-mail. An information form about the study was sent to the students and their parents, and consent for participation was obtained. All scales were administered simultaneously, online, in a single session, and in approximately 20 minutes for each participant.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Windows version 22.0 software. The relationships between the continuous variables were evaluated with the “Pearson correlation test”, and the relationships between the variables that did not fit normal distribution were evaluated with the “Spearman correlation test”. The mediation effect of the independent variables was tested with the “causal steps approach” of Baron and Kenny.[ 22 ] The statistical significance of the mediation effect was evaluated with the bootstrap method suggested by Preacher and Hayes.[ 23 ] P <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the participants, 67 (32.8%) were girls and 137 (67.2%) were boys. The mean age of all participants was 15.90 ± 1.20 years. The mean age of the mothers of the participants was 42.58 ± 4.76 years, and the mean age of their fathers was 46.49 ± 5.28 years. Among the mothers of the participants, 63 (30.9%) were primary school graduates, 60 (29.4%) were high school graduates, and 81 (39.7%) were university graduates. It was found that among the fathers of the participants, 51 (25%) were primary school graduates, 65 (31.9%) were high school graduates, and 88 (43.1%) were university graduates. The daily social media usage times of the participants were as less than 1 hour for 14 (6.9%) participants, 1-2 hours for 71 (34.8%) participants, 3-4 hours for 67 (32.8%) participants, and more than 4 hours for 52 (25.5%) participants.

The mean RSES, SMD-9, and MBSRQ scores of the participants are given in Table 1 .

The mean RSES, SMD-9, and MBSRQ scores of the participants

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSES | 0.00 | 6.00 | 4.39 | 1.43 |

| SMD-9 | 9.00 | 36.00 | 19.33 | 6.40 |

| MBSRQ total | 117.00 | 262.00 | 195.43 | 30.15 |

RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SMD-9: Social Media Use Disorder Scale; MBSRQ: Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire; SD: Standard deviation

Some significant results were obtained in the correlation analyses performed to evaluate the relationships between the examined variables. There was a negative moderate significant relationship between the RSES scores and SMD-9 scores of the participants ( P <.001), while there was a positive moderate significant relationship between their RSES and MBSRQ total scores ( P <.001). A negative, weak, and significant correlation was found between the SMD-9 and MBSRQ total scores of the participants ( P <.05; P <.001). No significant correlation was found between the RSES scores of the participants and their ages or parental education levels ( P >.05) [ Table 2 ].

Results of the correlation analyses between RSES scores and the ages, SMD-9 scores, and MBSRQ scores of the participants

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | -0.09 | -0.16* | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| 2. Education level (mother) | - | 0.06** | -0.09 | 0.09 | 0.01 | |

| 3. Education level (father) | - | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| 4. RSES | - | -0.35** | 0.40** | |||

| 5. SMD-9 | - | -0.15* | ||||

| 6. MBSRQ total | - |

* P <0.05, ** P <0.001; Pearson Correlation Test, Spearman Correlation Test; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SMD-9: Social Media Use Disorder Scale; MBSRQ: Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire

Table 2 . Results of the correlation analyses between RSES scores and the ages, SMD-9 scores, and MBSRQ scores of the participants.

The mediating role of body image (MBSRQ) in the relationship between self-esteem (RSES) and social media use (SMD-9) levels was examined in line with three conditions suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986). First, there must be a significant relationship between SMD-9 and MBSRQ, which are both independent variables, and RSES. Second, the mediator variable, MBSRQ, must be significantly related to the two examined variables, SMD-9 and RSES. Third, when the mediator variable is controlled, there should be a decrease in the degree of relationship between the two variables. A decrease in the degree of this relationship is accepted as an indicator of partial mediation, and the loss of significance of the relationship is accepted as an indicator of complete mediation. In the model that was established to test if the necessary criteria were met, the mediation effect of MBSRQ total scores on the relationship between SMD-9 and RSES scores was tested. Three separate regression equations, which are presented in Figure 1 , were created. As per the results of the regression analysis, SMD-9 scores had a direct and significant effect on RSES scores (B = -0.08; t = -5.45; P <.001). It was seen that SMD-9 scores significantly and directly predicted the mediating variable and MBSRQ total scores (B =-0.70; t = -2.16; P <.05). When the MBSRQ total scores variable was added to the model to evaluate its mediator role, it was found that the relationship between SMD-9 and RSES scores was still significant, but there was a decrease in the level of significance of this relationship. As a result of the analysis, it was determined that the MBSRQ total scores (B = -0.06; t =-4.93; P <.001) variable played a partial mediator role in the relationship between SMD-9 and RSES scores.

The mediator role of MBSRQ scores in the relationship between SMD-9 and RSES scores. * P < .05, ** P < .001; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SMD-9: Social Media Use Disorder Scale; MBSRQ: Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire

Whether the effects of the mediator variable were significant was examined using the bootstrap method. The bootstrap method is a nonparametric method based on resampling multiple times (1,000 or 5,000) by replacement. The indirect mediator effect is calculated for each new sample. The significance of the mediator effect is determined by calculating the most known confidence interval and whether there is a zero value in this interval. The absence of a zero value in the confidence interval indicates that the indirect effect is different from zero. As suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2008), the effects of the mediator variable on a 5,000-person bootstrap sample were examined. As per the results, the partial mediator effect of the MBSRQ total scores variable was significant in the relationship between RSES and SMD-9 scores (B = -0.01; 95% BCa CI [-0.024, -0.001]).

As per the results of this study, there was no significant relationship between the self-esteem levels of the adolescents and their ages and the education levels of their parents. There was a negative significant relationship between the self-esteem and social media addiction levels of the participants, while there was a positive significant relationship between their self-esteem and body image levels. As a result of the mediation analysis, the social media addiction levels of the participants were found to negatively predict their self-esteem and body image levels. It was determined that body image had a partial mediating effect in the relationship between self-esteem and social media addiction.

In studies examining the relationship between self-esteem and sociodemographic variables in adolescents, it was found that self-esteem did not vary significantly based on age.[ 24 ] In our study, in accordance with the literature, no significant relationship was found between the self-esteem levels of the participants and their age. Studies have mostly shown a significant relationship between parental education levels and the self-esteem levels of adolescents, and as the parental education levels increase, self-esteem levels also increase.[ 25 ] In our study, no significant relationship was found between the education levels of the parents of our participants and the self-esteem levels of the participants. Our results, which were inconsistent with the literature, may have occurred due to the small sample size.

It was shown that there is a correlation between self-esteem and social media use in adolescents.[ 26 ] In a study conducted by Woods and Scott with 467 adolescents, it was found that adolescents with high levels of social media use had low self-esteem.[ 27 ] Jan et al .[ 28 ] reported a negative correlation between the daily social media usage times and self-esteem levels of their participants. Thirty three studies on the subject published between 2008 and 2016 were examined in a meta-analysis study conducted by Liu and Baumeister.[ 29 ] In the study, it was reported that there was a negative relationship between social media use and self-esteem. In our study, it was found that the self-esteem and social media addiction levels of the participants were negatively related. Additionally, it was determined that social media addiction had a direct and significant effect on the self-esteem levels of the participants. It is known that the self-esteem levels of adolescents are negatively affected by mental disorders, especially depression and/or anxiety disorder.[ 30 ] The results of our study suggested that the self-esteem and social media addiction levels of adolescents are negatively related, similarly to the literature. However, the fact the mental health statuses of the participants were not assessed in our study limits the interpretability of the results.

Many studies have shown that self-esteem is related to body image in adolescents.[ 31 ] In a cross-sectional study, 290 participants were divided into two groups (12-15 years: early adolescence and 15-19 years: late adolescence), and a positive significant relationship was observed between the self-esteem and body image of the participants in both groups.[ 32 ] Almeida and Shivakumara reported a strong, positive, and significant relationship between the self-esteem and body image levels of the participants in a study that included 120 adolescents (age range: 11-19 years).[ 33 ] Similarly, in the literature, positive and significant relationships were found between the self-esteem levels and body images of adolescents, as in this study. An individual’s body image forms a whole with their self-concept and affects their personality, values, and social relationships as per theoreticians.[ 1 ] The body and body image, which are the most concrete parts of the self, are a significant reference in the identity development process of an adolescent.[ 34 ] It may be stated that the results of this study were expected due to the effect of body image in adolescence on self-esteem.

The mediator effect of body image in the relationship between the self-esteem and social media addiction levels of adolescents was investigated in our study. Our findings revealed that the adolescents’ body image levels played a partial mediator role in the relationship between their social media addiction levels and self-esteem levels. In the literature, no study examining the mediator role of body image in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem levels was found. However, there are studies evaluating the mediator role of body image in the relationship between social media use and other variables in adolescents. A study that was conducted with a large sample revealed that a negative body image had a direct and significant effect on the relationship between the social media use levels of adolescents and their depressive symptoms (mean age: 14 years).[ 35 ] Lee et al .[ 36 ] reported that body satisfaction was low in university students who used social media for information about body image, and a negative body image directly affected the psychological wellbeing of the participants. Studies examining the relationship between social media use and body image have demonstrated a significant positive relationship between a negative body image and frequency of social media use.[ 37 ] A study conducted with 1,087 female adolescents (between the ages of 13 and 15 years) determined that 75% of the participants had at least one social media account, and the negative body image levels of the participants who used social media were significantly higher than those who did not use social media.[ 38 ] A similar study pointed to a negative significant relationship between the time adolescents spent on social media and their status of having a positive body image.[ 39 ] The results of our study and those of other studies in the literature have shown a negative relationship between the social media addiction levels and body image of adolescents, and a less positive body image affects the self-esteem of adolescents negatively. It is known that body image is affected by sociocultural factors, and the media is an important factor in shaping the ideal body image of the individual.[ 40 ] The excessive use of social media may negatively affect the ideal body images of adolescents. A negative body image may cause a decrease in self-esteem.

Our results suggested that body image plays a partial mediator role in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem levels in adolescents. It is known that self-esteem in adolescents is very important in terms of identity development and mental health. It is emphasized that considering the effects of social media addiction and social media usage levels on body image and self-esteem in adolescents with low self-esteem is important both in the treatment of mental diseases known to be directly related to self-esteem and in terms of preventive mental health interventions.

Our study had some limitations. The self-esteem, body image, and social media addiction levels of the participants were measured only with self-reported scales. The lack of a diagnostic evaluation of adolescents by face-to-face interviews was an important limitation. Our study was a cross-sectional study. It is thought that longitudinal studies are needed to better explain the causal relationships between self-esteem and other variables.

Ethical approval

Ethics Committee approval for the study was received from Beykent University Publication Ethics Committee (July 24, 2020).

Financial support and sponsorship

No financial support or sponsorship was used for this research.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The relationship between social media addiction and young people should be investigated before designing the most suitable and symptomatically approach to prevent the addiction among youngsters ...

In addition, social media addiction can also lead to physical health problems, such as obesity and carpal tunnel syndrome a result of spending too much time on the computer . Apart from the negative impacts of social media addiction on users' mental and physical health, social media addiction can also lead to other problems. For example, social ...

social media utilization. This thesis will be structured as a literature review, focusing on the potential impact of social media on communication studies and its implications for addiction. In this thesis, I will look at recent articles on social media and social media addiction. Topics addressed will include

Introduction. Today, social media (SM) (e.g., WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, etc.) have enjoyed such rapidly-growing popularity[] that around 2.67 billion users of social networks have been estimated worldwide.[] After China, India, and Indonesia, Iran ranks fourth in terms of using SM, having approximately 40 million active online social network users over the past decade, these networks have ...

This research examined the relations of social media addiction to college students' mental health and academic performance, investigated the role of self-esteem as a mediator for the relations, and further tested the effectiveness of an intervention in reducing social media addiction and its potential adverse outcomes. In Study 1, we used a survey method with a sample of college students (N ...

In a study conducted by Kirik et al. on social media addiction with 271 undergraduates, no significant difference was found in terms of gender either. There are also studies in the literature showing that social media addiction of men is higher than in women [30,31,32]. Participants in the current study were using social media for an average of ...

social media addiction scales, or general addiction in a population, and theories or models that have been applied in studies of social media addiction. Yet, it appears that 70 these reviews have a limited focus and narrow perspective. They do not cover up-to-date facets of social media addiction among young users. For example, Sun and Zhang

First, I would like to thank my Primary Thesis Advisor Nick Allen from the Department of Psychology for all of his support and time helping me examine this ... 4.4 Social Media and Social Networking Site Addiction and Prolonged Periods of Use 14 5. Discussion 16 5.1 Moderators of Beneficial Effects of Social Media and Social Networking

Social media use can bring negative effects to college students, such as social media addiction (SMA) and decline in academic performance. SMA may increase the perceived stress level of college students, and stress has a negative impact on academic performance, but this potential mediating role of stress has not been verified in existing studies. In this paper, a research model was developed ...

In this study, we reviewed 25 distinct theories/models that guided the research design of 55 empirical studies of social media addiction to identify theoretical perspectives and constructs that have been examined to explain the development of social media addiction. Limitations of the existing theoretical frameworks were identified, and future ...

social media either posting about their experiences or viewing other posts. Though social media can be fun and sometimes useful, it can also have negative effects on mental health, especially in adolescence. Researchers have done studies on these effects and developed scales to measure impacts like social media addiction.