REQUEST A FREE SCREEN

Emotional and social benefits of physical activity.

You know exercise is good for you. You’ve heard it time and time again from doctors, teachers, coaches, friends, television programs, magazines, and more for as long as you can remember.

Of course, moving more helps keep our bodies in tip-top shape, from our muscles to our joints to our heart and lungs. But did you know that regular physical activity plays a significant role in our emotional and social health?

This guide explains everything you need to know about the social benefits of exercise at every stage of your life.

Table of Contents

How does physical activity benefit your social health.

- Top 5 Emotional and Social Benefits of Exercise

Social Benefits of Exercise for Children

Social benefits of exercise for teenagers, social benefits of exercise for adults.

- Social Benefits of Exercise for the Elderly

- Want to Learn More About The Social Benefits of Exercise? Connect With One of In Motion O.C’s Fitness Experts

Whether you get your sweat on with a fitness coach, with a friend or family member, or in a group fitness class, there are several benefits to working out with others . These include:

- Maintaining proper form

- A competitive push

- Staying accountable

When looking for a person or group of people to work out with, ideal qualities include:

- A positive attitude

- Similar health and fitness goals

- Compatible schedules

If regular exercise isn’t a part of your routine, getting started alongside a community of people dedicated to maintaining a healthy lifestyle may be what you need.

That’s what you can expect from In Motion O.C.

From our wide variety of fitness programs to aquatic therapy, In Motion O.C. provides a community of fitness professionals and a community of people committed to putting their health first for you to be a part of.

Top 5 Emotional and Social Benefits of Regular Exercise

Working out has several benefits. Controlling weight or building muscle may be two benefits that immediately come to mind.

Additional physical benefits of working out regularly include:

- Improved sleep

- Increased muscle and bone density

- Metabolic syndrome

- High blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes

- Many types of cancer

But maybe you haven’t thought about what else moving regularly can do to positively impact your life.

Let’s focus on the emotional and social benefits of physical activity. From neighborhood walks to yoga classes to strength training , working out helps you with:

- Building relationships

- Increasing energy levels

- Boosting your mood

- Discipline and accountability

- Improved cognitive function.

#1: Builds Relationships

Whether in person or virtually, working out with friends, a personal trainer, or in a class is a great way to build relationships with others.

Maybe you’ve moved to a new city, joining a gym or attending a regular workout class is a great way to meet people. After all, you’ll know you already share an interest. Workout classes and camaraderie often go hand-in-hand.

Or, maybe work and life has been extra busy, leaving little quality time to spend with a good friend or significant other.

Carving out an hour a few times each week for a walk, run, or bike ride with that person allows you time for uninterrupted conversation and an opportunity to get moving.

#2: Increased Energy

Do you find you’re worn out after running around after your toddler or winded after taking the stairs? You may think an afternoon nap or a jolt of caffeine may help with that exhaustion, but a better bet may be adding regular exercise into your daily routine.

Physical activity helps build our muscles and increases our endurance when it comes to completing everyday tasks.

On top of that, exercise improves heart and lung health , increasing energy levels.

#3: Mood Boosts

You may have friends or family who hit the gym when they’re feeling upset or go for a long run to blow off some steam. There’s a scientific reason for that.

You’ve likely heard of endorphins. Endorphins are the body’s “feel-good” neurotransmitters.

Physical activity increases endorphin levels, which in turn boosts your mood and decreases depression and anxiety.

If you’re feeling stressed out or down in the dumps, regular exercise may be just what the doctor ordered!

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends getting at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity each week.

#4: Discipline

Think about this.

Are you one of those people who say they’re going to work out each morning?

You lay out your workout gear, prep your water bottle, and set your alarm to go off well before the sun rises.

You’ve got the best of intentions, but hours later, when that alarm starts beeping, you start making excuses:

- “ I didn’t get enough sleep .”

- “ I’m not feeling well .”

- “I’ll hit the gym early tomorrow morning instead.”

If you find you’re making excuses, hitting snooze, and going back to sleep more often than sweating before sunrise, having an accountability partner may be exactly what you need.

After all, you’re less likely to blow off that morning workout if a friend or fitness coach is waiting on you.

Having an accountability partner encourages healthy habits and discipline.

#5: Improved Cognitive Function

You may have heard people complain of “brain fog” or say they’re going to hit the treadmill to “clear their head.”

That’s because there’s a correlation between regular exercise and improved cognitive function.

Studies have shown that aerobic exercise boosts the size of the brain area associated with verbal memory and learning .

What Are the Social Benefits of Exercise By Age Group?

No matter if you’re…

- Learning Tae Kwon Do as a six-year-old

- Playing high school soccer

- Training for a marathon with your best friend in your 30s, or

- Strength training with your significant other so you can keep up with your grandkids

…regular exercise provides social benefits at every age.

If you invest in yourself by working out, you can expect positive impacts from increased confidence to lower stress to a group of friends to socialize with and who support your fitness goals.

Physical play isn’t just enjoyable for kids; it’s essential for their wellbeing, both cognitively and socially.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least 60 minutes of physical activity daily for children six years and older.

This activity helps kids:

- Develop social skills

- Encourages team-building

- Improve self-esteem

- Boosts academic performance

The teenage years aren’t easy. Teens deal with changing bodies, increased responsibilities, and a host of social stressors.

Besides managing weight and keeping young adults healthy, exercise helps teens:

- Manage stress levels

- Process difficult emotions

- Build confidence

Whether it’s getting involved in a team sport at school, going on hikes or bike rides with a friend, routine activity needs to be a priority for adolescents.

As we move into adulthood, exercise remains essential for both our physical and social health. It also becomes more challenging to make regular exercise a priority in this season of life.

After all, as adults, we’re often responsible for more than just ourselves. We may be responsible for:

- Young children

- Aging parents

- Managing colleagues and co-workers

- Managing finances

- And much more

Despite all of the things that demand our time and energy, making time for regular exercise provides a host of benefits:

- Improved self-esteem

- Stress relief

- Increased energy

- Improved quality of life

- Longer life expectancy

Social Benefits of Exercise for Elderly Individuals

Regular exercise is vital for older adults.

Not only does it improve overall health and fitness, but increased physical activity also reduces your risk of chronic conditions.

Strength training is a great place to start because muscle mass naturally diminishes with age. Strength training can help you preserve and enhance that muscle mass.

Regular exercise, specifically strength training and high impact cardio, can also slow the loss of bone density that often comes with age.

In addition to:

- Preventing disease

- Preserving muscle mass

- Increasing bone density

Regular exercise is key to improving mental health and wellbeing. One way to feel happy and confident as we age is by maintaining our physical and psychological independence.

Increased Independence

Getting older comes with its own challenges. It can be downright frustrating when our bodies can’t do the things they were once able to.

At In Motion O.C., our clients want to feel good when they play with their kids or grandkids.

They want to work out in such a way as to maximize their health and wellbeing, not just their biceps. That’s why our fitness coaches focus on functional strength training .

Functional strength training may be especially beneficial as part of a comprehensive program for older adults to:

- Improve balance

- Improve agility

- Increase muscle strength

- Reduce the risk of falls

Many older adults hope to continue to live in their own homes as long as possible, as opposed to moving to an assisted living center or other care facility.

If maintaining that independence is important to you, now is the time to get moving.

Regular exercise helps seniors stay mobile , increasing their ability to complete everyday tasks and live independently.

Want to Learn More About The Social Benefits of Exercise? Connect With One of In Motion O.C’s Fitness Experts

Do you want to experience the many emotional and social benefits of exercise firsthand?

Start your journey to better physical, mental, and social health with a free consultation.

In Motion O.C. isn’t just a physical therapy clinic. It isn’t just a gym.

When you become part of the In Motion O.C. family, you’re welcomed into a community of like-minded individuals. When you walk through the doors of this state-of-the-art facility, you’ll know you’re in a place where your health is our #1 priority.

In Motion O.C. is your alternative to large, impersonal gyms.

That’s because, at In Motion O.C., we focus on real relationships with our members. Our team of fitness professionals will get to know your personal goals and help you reach and exceed them.

Whether you’re beginning your fitness journey or you’re a seasoned athlete, when you join the In Motion O.C. family, you’re getting:

- A top-level fitness coach

- A workout program co-designed by physical therapists, postural specialists, and fitness coaches

- Free consultations with physical therapists whenever needed

Make a commitment to your physical, mental, and social wellness with a fitness program and wellness community today. In Motion O.C. will be with you every step of the way.

Related Posts

- Does Physical Therapy Work? How You Can Benefit From Physical Therapy Fitness

- Are You Overtraining and Undereating? Fitness

- Rowing Machine vs. Stationary Bike: Choosing the Right Machine for Your Workout Fitness

- Nonbody-Part Specific

- Sacroiliac Joint

- Performance Therapy

- Specialty Programs

- Online Scheduling

- Video for New Patients

- Massage Therapy

- Jobs at InMotion O.C.

- Community Involvement

- Our History

- Mission Statement

Between October 18–21, this website will move to a new web address (from health.gov to odphp.health.gov). During that time, some functions might not work as expected. We appreciate your patience and understanding as we’re working to make this transition as smooth as possible.

Physical Activity Is Good for the Mind and the Body

Health and Well-Being Matter is the monthly blog of the Director of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Everyone has their own way to “recharge” their sense of well-being — something that makes them feel good physically, emotionally, and spiritually even if they aren’t consciously aware of it. Personally, I know that few things can improve my day as quickly as a walk around the block or even just getting up from my desk and doing some push-ups. A hike through the woods is ideal when I can make it happen. But that’s me. It’s not simply that I enjoy these activities but also that they literally make me feel better and clear my mind.

Mental health and physical health are closely connected. No kidding — what’s good for the body is often good for the mind. Knowing what you can do physically that has this effect for you will change your day and your life.

Physical activity has many well-established mental health benefits. These are published in the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and include improved brain health and cognitive function (the ability to think, if you will), a reduced risk of anxiety and depression, and improved sleep and overall quality of life. Although not a cure-all, increasing physical activity directly contributes to improved mental health and better overall health and well-being.

Learning how to routinely manage stress and getting screened for depression are simply good prevention practices. Awareness is especially critical at this time of year when disruptions to healthy habits and choices can be more likely and more jarring. Shorter days and colder temperatures have a way of interrupting routines — as do the holidays, with both their joys and their stresses. When the plentiful sunshine and clear skies of temperate months give way to unpredictable weather, less daylight, and festive gatherings, it may happen unconsciously or seem natural to be distracted from being as physically active. However, that tendency is precisely why it’s so important that we are ever more mindful of our physical and emotional health — and how we can maintain both — during this time of year.

Roughly half of all people in the United States will be diagnosed with a mental health disorder at some point in their lifetime, with anxiety and anxiety disorders being the most common. Major depression, another of the most common mental health disorders, is also a leading cause of disability for middle-aged adults. Compounding all of this, mental health disorders like depression and anxiety can affect people’s ability to take part in health-promoting behaviors, including physical activity. In addition, physical health problems can contribute to mental health problems and make it harder for people to get treatment for mental health disorders.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the need to take care of our physical and emotional health to light even more so these past 2 years. Recently, the U.S. Surgeon General highlighted how the pandemic has exacerbated the mental health crisis in youth .

The good news is that even small amounts of physical activity can immediately reduce symptoms of anxiety in adults and older adults. Depression has also shown to be responsive to physical activity. Research suggests that increased physical activity, of any kind, can improve depression symptoms experienced by people across the lifespan. Engaging in regular physical activity has also been shown to reduce the risk of developing depression in children and adults.

Though the seasons and our life circumstances may change, our basic needs do not. Just as we shift from shorts to coats or fresh summer fruits and vegetables to heartier fall food choices, so too must we shift our seasonal approach to how we stay physically active. Some of that is simply adapting to conditions: bundling up for a walk, wearing the appropriate shoes, or playing in the snow with the kids instead of playing soccer in the grass.

Sometimes there’s a bit more creativity involved. Often this means finding ways to simplify activity or make it more accessible. For example, it may not be possible to get to the gym or even take a walk due to weather or any number of reasons. In those instances, other options include adding new types of movement — such as impromptu dance parties at home — or doing a few household chores (yes, it all counts as physical activity).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I built a makeshift gym in my garage as an alternative to driving back and forth to the gym several miles from home. That has not only saved me time and money but also afforded me the opportunity to get 15 to 45 minutes of muscle-strengthening physical activity in at odd times of the day.

For more ideas on how to get active — on any day — or for help finding the motivation to get started, check out this Move Your Way® video .

The point to remember is that no matter the approach, the Physical Activity Guidelines recommend that adults get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (anything that gets your heart beating faster) each week and at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activity (anything that makes your muscles work harder than usual). Youth need 60 minutes or more of physical activity each day. Preschool-aged children ages 3 to 5 years need to be active throughout the day — with adult caregivers encouraging active play — to enhance growth and development. Striving toward these goals and then continuing to get physical activity, in some shape or form, contributes to better health outcomes both immediately and over the long term.

For youth, sports offer additional avenues to more physical activity and improved mental health. Youth who participate in sports may enjoy psychosocial health benefits beyond the benefits they gain from other forms of leisure-time physical activity. Psychological health benefits include higher levels of perceived competence, confidence, and self-esteem — not to mention the benefits of team building, leadership, and resilience, which are important skills to apply on the field and throughout life. Research has also shown that youth sports participants have a reduced risk of suicide and suicidal thoughts and tendencies. Additionally, team sports participation during adolescence may lead to better mental health outcomes in adulthood (e.g., less anxiety and depression) for people exposed to adverse childhood experiences. In addition to the physical and mental health benefits, sports can be just plain fun.

Physical activity’s implications for significant positive effects on mental health and social well-being are enormous, impacting every facet of life. In fact, because of this national imperative, the presidential executive order that re-established the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition explicitly seeks to “expand national awareness of the importance of mental health as it pertains to physical fitness and nutrition.” While physical activity is not a substitute for mental health treatment when needed and it’s not the answer to certain mental health challenges, it does play a significant role in our emotional and cognitive well-being.

No matter how we choose to be active during the holiday season — or any season — every effort to move counts toward achieving recommended physical activity goals and will have positive impacts on both the mind and the body. Along with preventing diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and the additional risks associated with these comorbidities, physical activity’s positive effect on mental health is yet another important reason to be active and Move Your Way .

As for me… I think it’s time for a walk. Happy and healthy holidays, everyone!

Yours in health, Paul

Paul Reed, MD Rear Admiral, U.S. Public Health Service Deputy Assistant Secretary for Health Director, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review

Aditya mahindru, pradeep patil, varun agrawal.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Aditya Mahindru [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2022 Oct 12; Accepted 2023 Jan 7; Collection date 2023 Jan.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

In addition to the apparent physical health benefits, physical activity also affects mental health positively. Physically inactive individuals have been reported to have higher rates of morbidity and healthcare expenditures. Commonly, exercise therapy is recommended to combat these challenges and preserve mental wellness. According to empirical investigations, physical activity is positively associated with certain mental health traits. In nonclinical investigations, the most significant effects of physical exercise have been on self-concept and body image. An attempt to review the current understanding of the physiological and psychological mechanisms by which exercise improves mental health is presented in this review article. Regular physical activity improves the functioning of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Depression and anxiety appear to be influenced by physical exercise, but to a smaller extent in the population than in clinical patients. Numerous hypotheses attempt to explain the connection between physical fitness and mental wellness. Physical activity was shown to help with sleep and improve various psychiatric disorders. Exercise in general is associated with a better mood and improved quality of life. Physical exercise and yoga may help in the management of cravings for substances, especially in people who may not have access to other forms of therapy. Evidence suggests that increased physical activity can help attenuate some psychotic symptoms and treat medical comorbidities that accompany psychotic disorders. The dearth of literature in the Indian context also indicated that more research was needed to evaluate and implement interventions for physical activity tailored to the Indian context.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, morbidity, mental health, physical activity

Introduction and background

Physical activity has its origins in ancient history. It is thought that the Indus Valley civilization created the foundation of modern yoga in approximately 3000 B.C. during the early Bronze Age [ 1 ]. The beneficial role of physical activity in healthy living and preventing and managing health disorders is well documented in the literature. Physical activity provides various significant health benefits. Mechanical stress and repeated exposure to gravitational forces created by frequent physical exercise increase a variety of characteristics, including physical strength, endurance, bone mineral density, and neuromusculoskeletal fitness, all of which contribute to a functional and independent existence. Exercise, defined as planned, systematic, and repetitive physical activity, enhances athletic performance by improving body composition, fitness, and motor abilities [ 2 ]. The function of physical activity in preventing a wide range of chronic illnesses and premature mortality has been extensively examined and studied. Adequate evidence links medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease and individual lifestyle behaviours, particularly exercise [ 3 ]. Regular exercise lowered the incidence of cardiometabolic illness, breast and colon cancer, and osteoporosis [ 4 ]. In addition to improving the quality of life for those with nonpsychiatric diseases such as peripheral artery occlusive disease and fibromyalgia, regular physical activity may help alleviate the discomforts of these particular diseases [ 5 ]. Exercise also helps with various substance use disorders, such as reducing or quitting smoking. As physical exercise strongly impacts health, worldwide standards prescribe a weekly allowance of "150 minutes" of modest to vigorous physical exercise in clinical and non-clinical populations [ 6 ]. When these recommendations are followed, many chronic diseases can be reduced by 20%-30%. Furthermore, thorough evaluations of global studies have discovered that a small amount of physical exercise is sufficient to provide health benefits [ 7 ].

Methodology

In this review article, a current understanding of the underlying physiological and psychological processes during exercise or physical activity that are implicated in improving mental health is presented. Search terms like "exercise" or "physical activity" and "mental health", "exercise" or "physical activity" and "depression", "exercise" or "physical activity" and "stress", "exercise" or "physical activity" and "anxiety", "exercise" or "physical activity" and "psychosis," "exercise" or "physical activity" and "addiction" were used as search terms in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Medline. An overwhelming majority of references come from works published within the past decade.

The impact of physical health on mental health

There is an increasing amount of evidence documenting the beneficial impacts of physical activity on mental health, with studies examining the effects of both brief bouts of exercise and more extended periods of activity. Systematic evaluations have indicated better outcomes for mental diseases with physical activity. Numerous psychological effects, such as self-esteem, cognitive function, mood, depression, and quality of life, have been studied [ 8 ]. According to general results, exercise enhances mood and self-esteem while decreasing stress tendencies, a factor known to aggravate mental and physical diseases [ 9 ]. Studies show that people who exercise regularly have a better frame of mind. However, it should be highlighted that a consistent link between mood enhancement and exercise in healthy individuals has not been established.

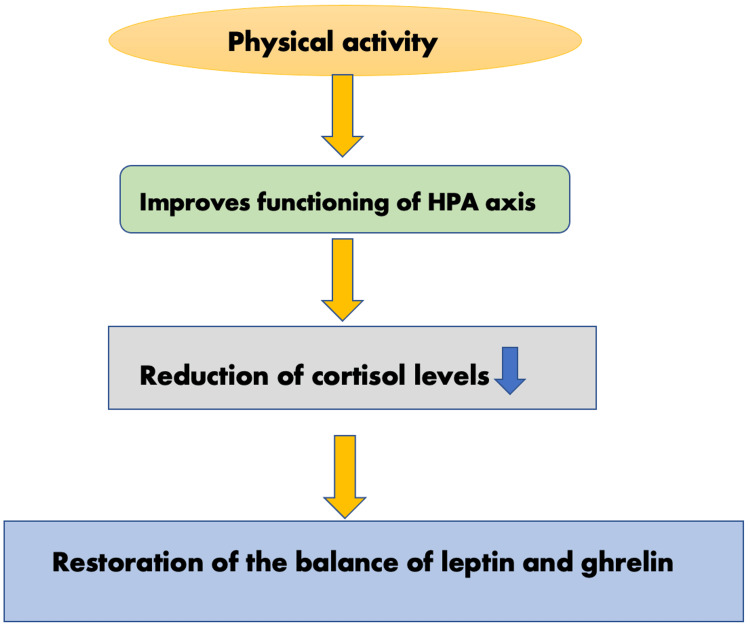

Additionally, human beings produce more of these two neurochemicals when they engage in physical activity. Human bodies manufacture opioids and endocannabinoids that are linked to pleasure, anxiolytic effects, sleepiness, and reduced pain sensitivity [ 10 ]. It has been shown that exercise can improve attention, focus, memory, cognition, language fluency, and decision-making for up to two hours [ 11 ]. Researchers state that regular physical activity improves the functioning of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, lowering cortisol secretion and restoring the balance of leptin and ghrelin (Figure 1 ) [ 12 ].

Figure 1. The effects of physical activity on the HPA axis.

HPA: hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal

This image has been created by the authors.

Regular exercise has immunomodulatory effects such as optimising catecholamine, lowering cortisol levels, and lowering systemic inflammation. Physical activity has been shown to increase plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is thought to reduce amyloid-beta toxicity linked to Alzheimer's disease progression [ 13 ].

Although no causal correlations have been proven, methodologically sound research has discovered a related improvement in mentally and physically ill populations. These findings are based on research and studies conducted all across the globe, particularly in the Western Hemisphere. In order to address a widespread health problem in India, it is useful to do a literature review that draws on research conducted in a variety of settings. In addition, the prevalence of these mental illnesses and the benefits of exercise as a complementary therapy might be made clear by a meta-analysis of research undertaken in India [ 14 ].

This review also analysed published literature from India to understand the effects of exercise on mental health and the implications for disease management and treatment in the Indian context. Results from Indian studies were consistent with those found in global meta-analyses. The Indian government has made public data on interventions, such as the effects of different amounts of physical exercise. Exercising and yoga have been shown to be effective adjunct therapies for a variety of mental health conditions [ 12 ]. Though yoga may not require a lot of effort to perform, other aspects of the program, such as breathing or relaxation exercises, may have an impact on a practitioner's mental health at the same time. Due to its cultural significance as a common physical practice among Indians and its low to moderate activity level, yoga would be an appropriate activity for this assessment [ 15 ].

Yoga as an adjunctive treatment

Although yoga is a centuries-old Hindu practice, its possible therapeutic effects have recently been studied in the West. Mind-body approaches have been the subject of a lot of studies, and some of the findings suggest they may aid with mental health issues on the neurosis spectrum. As defined by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, "mind-body interventions" aim to increase the mind's potential to alter bodily functions [ 16 ]. Due to its beneficial effects on the mind-body connection, yoga is used as a treatment for a wide range of conditions. Possible therapeutic benefits of yoga include the activation of antagonistic neuromuscular systems, stimulation of the limbic system, and a reduction in sympathetic tone.

Anxiety and depression sufferers might benefit from practising yoga. Yoga is generally safe for most people and seldom causes unintended negative consequences. Adding yoga to traditional treatment for mental health issues may be beneficial. Many of the studies on yoga included meditation as an integral part of their methodology. Meditation and other forms of focused mental practice may set off a physiological reaction known as the relaxation response. Functional imaging has been used to implicate certain regions of the brain that show activity during meditation. According to a wealth of anatomical and neurochemical evidence, meditation has been shown to have far-reaching physiological effects, including changes in attention and autonomic nervous system modulation [ 17 ]. Left anterior brain activity, which is associated with happiness, was shown to rise considerably during meditation. There's also some evidence that meditation might worsen psychosis by elevating dopamine levels [ 18 - 20 ]. We do not yet know enough about the possible downsides of meditation for patients with mental illness, since this research lacks randomised controlled trials.

Physical activity and schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a debilitating mental disorder that often manifests in one's early years of productive life (late second decade). Remission of this disorder occurs in just a small fraction of cases. More than 60% will have relapses, and they might occur with or without noticeable deficits. Apart from delusions, hallucinations, and formal thought disorders, many patients exhibit cognitive deficits that emerge in the early stages of the disease and do not respond adequately to therapy [ 21 ].

Treatment for schizophrenia is challenging to master. Extrapyramidal side effects are a problem with first-generation antipsychotic drugs. Obesity and dyslipidemia have been related to second-generation drugs, which may cause or exacerbate these conditions. The majority of patients do not achieve complete remission, and many do not even experience satisfactory symptom relief. Even though certain antipsychotic medications may alleviate or even exacerbate negative and cognitive symptoms, these responses are far less common. This means that patients may benefit from cognitive rehabilitation. Because of their illness or a negative reaction to their medicine, they may also have depressive symptoms. This would make their condition even more disabling. Many patients also deal with clinical and emotional complications. Tardive extrapyramidal illnesses, metabolic syndromes, defect states, and attempted suicide are all in this category. Patient compliance with treatment plans is often poor. The caregivers take on a lot of stress and often get exhausted as a result.

Evidence suggests that increased physical activity can aid in attenuating some psychotic symptoms and treating medical comorbidities that accompany psychotic disorders, particularly those subject to the metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotics. Physically inactive people with mental disorders have increased morbidity and healthcare costs. Exercise solutions are commonly recommended to counteract these difficulties and maintain mental and physical wellness [ 22 ].

The failure of current medications to effectively treat schizophrenia and the lack of improvement in cognitive or negative symptoms with just medication is an argument in favour of utilising yoga as a complementary therapy for schizophrenia. Even without concomitant medication therapy, co-occurring psychosis and obesity, or metabolic syndrome, are possible. The endocrine and reproductive systems of drug abusers undergo subtle alterations. Numerous studies have shown that yoga may improve endocrine function, leading to improvements in weight management, cognitive performance, and menstrual regularity, among other benefits. In this context, the role of yoga in the treatment of schizophrenia has been conceptualized. However, yoga has only been studied for its potential efficacy as a therapy in a tiny number of studies. There might be several reasons for this. To begin with, many yoga academies frown against the practice being adapted into a medical modality. The second misconception is that people with schizophrenia cannot benefit from the mental and physical aspects of yoga practised in the ways that are recommended. Third, scientists may be hesitant to recommend yoga to these patients because of their lack of knowledge and treatment compliance.

In a randomised controlled experiment with a yoga group (n = 21) and an exercise group (n = 20), the yoga group exhibited a statistically significant reduction in negative symptoms [ 2 ]. In accordance with the most recent recommendations of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the above research provides substantial evidence for the use of yoga in the treatment of schizophrenia. According to a meta-analysis of 17 distinct studies [ 23 ] on the subject, frequent physical activity reduces the negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia considerably.

Physical activity and alcohol dependence syndrome

Substance abuse, namely alcohol abuse, may have devastating effects on a person's mental and physical health. Tolerance and an inability to control drinking are some hallmarks of alcoholism. Research shows that physical activity is an effective supplement in the fight against alcohol use disorder. In addition to perhaps acting centrally on the neurotransmitter systems, physical exercise may mitigate the deleterious health consequences of drinking. Evidence suggests that persons with alcohol use disorder are not physically active and have low cardiorespiratory fitness. A wide number of medical comorbidities, like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and other cardiovascular illnesses, occur with alcohol use disorders. Physical exercise may be highly useful in aiding the management of these comorbidities [ 24 ].

Physical exercise and yoga may help in the management of cravings for substances when other forms of therapy, such as counselling or medication for craving management are not feasible or acceptable. Physical exercise has been shown to have beneficial effects on mental health, relieve stress, and provide an enjoyable replacement for the substance. However, the patient must take an active role in physical activity-based therapies rather than passively accept the process as it is, which is in stark contrast to the approach used by conventional medicine. Since most substance use patients lack motivation and commitment to change, it is recommended that physical activity-based therapies be supplemented with therapies focusing on motivation to change to maximise therapeutic outcomes.

One hundred seventeen persons with alcohol use disorder participated in a single-arm, exploratory trial that involved a 12-minute fitness test using a cycle ergometer as an intervention. Statistically, significantly fewer cravings were experienced by 40% [ 24 ]. Exercise programmes were found to significantly reduce alcohol intake and binge drinking in people with alcohol use disorder in a meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the effects of such therapies [ 25 ].

Physical activity and sleep

Despite widespread agreement that they should prioritise their health by making time for exercise and sufficient sleep, many individuals fail to do so. Sleep deprivation has negative impacts on immune system function, mood, glucose metabolism, and cognitive ability. Slumber is a glycogenetic process that replenishes glucose storage in neurons, in contrast to the waking state, which is organised for the recurrent breakdown of glycogen. Considering these findings, it seems that sleep has endocrine effects on the brain that are unrelated to the hormonal control of metabolism and waste clearance at the cellular level. Several factors have been proposed as potential triggers for this chain reaction: changes in core body temperature, cytokine concentrations, energy expenditure and metabolic rate, central nervous system fatigue, mood, and anxiety symptoms, heart rate and heart rate variability, growth hormone and brain-derived neurotrophic factor secretion, fitness level, and body composition [ 26 ].

After 12 weeks of fitness training, one study indicated that both the quantity and quality of sleep in adolescents improved. Studies using polysomnography indicated that regular exercise lowered NREM stage N1 (very light sleep) and raised REM sleep (and REM sleep continuity and performance) [ 22 ]. As people age, both short- and long-term activities have increasingly deleterious effects on sleep. In general, both short- and long-term exercise were found to have a favourable effect on sleep quality; however, the degree of this benefit varied substantially among different sleep components. On measures of sleep quality, including total sleep time, slow-wave sleep, sleep onset latency, and REM sleep reduction, acute exercise had no effect. But both moderate and strenuous exercise has been shown to increase sleep quality [ 27 ]. According to a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, exercise has shown a statistically significant effect on sleep quality in adults with mental illness [ 28 ]. These findings emphasise the importance that exercise plays in improving outcomes for people suffering from mental illnesses.

Physical activity in depressive and anxiety disorders

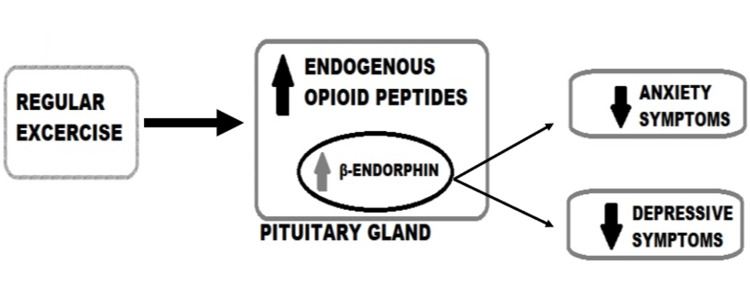

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the global burden of disease, as per the World Health Organization. However, only 10%-25% of depressed people actually seek therapy, maybe due to a lack of money, a lack of trained doctors, or the stigma associated with depression [ 29 ]. For those with less severe forms of mental illness, such as depression and anxiety, regular physical exercise may be a crucial part of their treatment and management. Exercise and physical activity might improve depressive symptoms in a way that is comparable to, if not more effective than, traditional antidepressants. However, research connecting exercise to a decreased risk of depression has not been analysed in depth [ 30 ]. Endorphins, like opiates, are opioid polypeptide compounds produced by the hypothalamus-pituitary system in vertebrates in response to extreme physical exertion, emotional arousal, or physical pain. The opioid system may mediate analgesia, social bonding, and depression due to the link between b-endorphins and depressive symptoms (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2. Flow chart demonstrating the link between beta-endorphins and depressive and anxiety symptoms.

The "endorphin hypothesis" states that physical activity causes the brain to produce more endogenous opioid peptides, which reduce pain and boost mood. The latter reduces feelings of worry and hopelessness. A recent study that demonstrated endorphins favourably improved mood during exercise, and provided support for these theories suggested that further research into the endorphin theory is required [ 31 ].

Physical activity and exercise have been shown to improve depressive symptoms and overall mood in people of all ages. Exercise has been implicated in lowering depressive and anxious symptoms in children and adolescents as well [ 32 ]. Pooled research worldwide has revealed that physical exercise is more effective than a control group and is a viable remedy for depression [ 33 ]. Most forms of yoga that start with a focus on breathing exercises, self-awareness, and relaxation techniques have a positive effect on depression and well-being [ 34 ]. Despite claims that exercise boosts mood, the optimal kind or amount of exercise required to have this effect remains unclear and seems to depend on a number of factors [ 35 ].

Exercise as a therapy for unipolar depression was studied in a meta-analysis of 23 randomised controlled trials involving 977 subjects. The effect of exercise on depression was small and not statistically significant at follow-up, although it was moderate in the initial setting. When compared to no intervention, the effect size of exercise was large and significant, and when compared to normal care, it was moderate but still noteworthy [ 36 ]. A systematic evaluation of randomised controlled trials evaluating exercise therapies for anxiety disorders indicated that exercise appeared useful as an adjuvant treatment for anxiety disorders but was less effective than antidepressant treatment [ 37 ].

Conclusions

The effects of exercise on mental health have been shown to be beneficial. Among persons with schizophrenia, yoga was shown to have more positive effects with exercise when compared with no intervention. Consistent physical activity may also improve sleep quality significantly. Patients with alcohol dependence syndrome benefit from a combination of medical therapy and regular exercise since it motivates them to battle addiction by decreasing the craving. There is also adequate evidence to suggest that physical exercise improves depressive and anxiety symptoms. Translating the evidence of the benefits of physical exercise on mental health into clinical practice is of paramount importance. Future implications of this include developing a structured exercise therapy and training professionals to deliver it. The dearth of literature in the Indian context also indicates that more research is required to evaluate and implement interventions involving physical activity that is tailored to the Indian context.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- 1. Positive impact of prescribed physical activity on symptoms of schizophrenia: randomized clinical trial. Curcic D, Stojmenovic T, Djukic-Dejanovic S, et al. Psychiatr Danub. 2017;29:459–465. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2017.459. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia--a randomized controlled trial. Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Yoga therapy for schizophrenia. Bangalore NG, Varambally S. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:85–91. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.98212. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Depression among Indian university students and its association with perceived university academic environment, living arrangements and personal issues. Deb S, Banu PR, Thomas S, Vardhan RV, Rao PT, Khawaja N. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;23:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.07.010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Physical activity and mental health: the association between exercise and mood. Peluso MA, Guerra de Andrade LH. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2005;60:61–70. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000100012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Effect of yoga therapy on facial emotion recognition deficits, symptoms and functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Behere RV, Arasappa R, Jagannathan A, et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01605.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13 doi: 10.4088/PCC.10r01068. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Physical activity and mental health: evidence is growing. Biddle S. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:176–177. doi: 10.1002/wps.20331. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Functional improvement and social participation through sports activity for children with mental retardation: a field study from a developing nation. Ghosh D, Datta TK. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36:339–347. doi: 10.1177/0309364612451206. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Effects of suryanamaskar on relaxation among college students with high stress in Pune, India. Godse AS, Shejwal BR, Godse AA. Int J Yoga. 2015;8:15–21. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.146049. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. "Happy feet": evaluating the benefits of a 100-day 10,000 step challenge on mental health and wellbeing. Hallam KT, Bilsborough S, de Courten M. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:19. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1609-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Increased mental well-being and reduced state anxiety in teachers after participation in a residential yoga program. Telles S, Gupta RK, Bhardwaj AK, Singh N, Mishra P, Pal DK, Balkrishna A. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2018;24:105–112. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.909200. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Effect of yoga on different aspects of mental health. Telles S, Singh N, Yadav A, Balkrishna A. https://www.ijpp.com/IJPP%20archives/2012_56_3_%20July%20-%20Sep/IJPP_2012_Vol_56_3_Final.pdf#page=56 . Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;56:245–254. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Yoga in schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Vancampfort D, Vansteelandt K, Scheewe T, Probst M, Knapen J, De Herdt A, De Hert M. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01865.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Therapeutic efficacy of add-on yogasana intervention in stabilized outpatient schizophrenia: randomized controlled comparison with exercise and waitlist. Varambally S, Gangadhar BN, Thirthalli J, et al. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:227–232. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102414. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? [ Sep; 2023 ]. 2022. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name

- 17. Emotional style and susceptibility to the common cold. Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Turner RB, Alper CM, Skoner DP. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:652–657. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077508.57784.da. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Mania precipitated by meditation: a case report and literature review. Yorston GA. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2001;4:209–213. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Precipitation of acute psychotic episodes by intensive meditation in individuals with a history of schizophrenia. Walsh R, Roche L. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:1085–1086. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.8.1085. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Psychiatric problems precipitated by transcendental meditation. Lazarus AA. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/790439/ Psychol Rep. 1976;39:601–602. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1976.39.2.601. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Enduring negative symptoms in first-episode psychosis: comparison of six methods using follow-up data. Edwards J, McGorry PD, Waddell FM, Harrigan SM. Schizophr Res. 1999;40:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00043-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Physical activity and sleep quality in relation to mental health among college students. Ghrouz AK, Noohu MM, Dilshad Manzar M, Warren Spence D, BaHammam AS, Pandi-Perumal SR. Sleep Breath. 2019;23:627–634. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-01780-z. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Meditation-based mind-body therapies for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. Sabe M, Sentissi O, Kaiser S. Schizophr Res. 2019;212:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.07.030. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Physical activity as treatment for alcohol use disorders (FitForChange): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Hallgren M, Andersson V, Ekblom Ö, Andréasson S. Trials. 2018;19:106. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2435-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Exercise as a useful intervention to reduce alcohol consumption and improve physical fitness in individuals with alcohol use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lardier DT, Coakley KE, Holladay KR, Amorim FT, Zuhl MN. Front Psychol. 2021;12:675285. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.675285. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Interrelationship between sleep and exercise: a systematic review. Dolezal BA, Neufeld EV, Boland DM, Martin JL, Cooper CB. Adv Prev Med. 2017;2017:1364387. doi: 10.1155/2017/1364387. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Effects of exercise timing on sleep architecture and nocturnal blood pressure in prehypertensives. Fairbrother K, Cartner B, Alley JR, Curry CD, Dickinson DL, Morris DM, Collier SR. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2014;10:691–698. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S73688. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Does exercise improve sleep quality in individuals with mental illness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lederman O, Ward PB, Firth J, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;109:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.11.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression. Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0633-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:633–638. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Lessons in exercise neurobiology: the case of endorphins. Dishman RK, O’Connor PJ. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2009;2(1):4–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Larun L, Nordheim LV, Ekeland E, Hagen KB, Heian F. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:0. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004691.pub2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Physical activity and quality of life among adults with Paraplegia in Odisha, India. Ganesh S, Mishra C. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16:0–61. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2016.16.01.010. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:357–368. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Role of exercise in the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Manthou E, Georgakouli K, Fatouros IG, Gianoulakis C, Theodorakis Y, Jamurtas AZ. Biomed Rep. 2016;4:535–545. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.626. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Exercise for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Jayakody K, Gunadasa S, Hosker C. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:187–196. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091287. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (279.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

Hope, Happiness And Social Connection: Hidden Benefits Of Regular Exercise

Stephanie O'Neill

In a new book The Joy of Movement: How Exercise Helps Us Find Happiness, Hope, Connection, and Courage, author Kelly McGonigal argues that we should look beyond weight loss to the many social and emotional benefits of exercise. Boris Austin/Getty Images hide caption

In a new book The Joy of Movement: How Exercise Helps Us Find Happiness, Hope, Connection, and Courage, author Kelly McGonigal argues that we should look beyond weight loss to the many social and emotional benefits of exercise.

If ever there was a time to up your fitness game, the arrival of the new year and the new decade is it. But after the allure of the new gym membership wears off, our sedentary habits, more often than not, consume our promise of daily workouts. It doesn't have to be this way, says health psychologist and author, Kelly McGonigal .

In her new book, The Joy of Movement: How Exercise Helps Us Find Happiness, Hope, Connection, and Courage, the Stanford University lecturer offer new motivation to get moving that has less to do with how we look, or feeling duty-bound to exercise, and everything to do with how movement makes us feel. She shares with readers the often profound, yet lesser-known benefits of exercise that make it a worthy, lifelong activity whether you're young, old, fit or disabled.

The Joy of Movement

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

"I want them to understand [exercise] in a different way than the usual conversation we always have about weight loss, preventing disease and making our bodies look a certain way," McGonigal tells NPR.

Among its many life-altering rewards: the generation of hope, happiness, a sense of purpose, greater life satisfaction and rewarding connections with others.

"These benefits are seen throughout the life span," she writes. "They apply to every socioeconomic strata and appear to be culturally universal."

And they aren't activity-specific and they don't require you to be a superathlete. Whether you run, swim, dance, bike, lift weights, do yoga or participate in team sports — it doesn't matter, McGonigal says — moderate physical activity does far more than make us physically stronger and healthier.

Here are five of the ways movement can help you enjoy life.

1) Activate pleasure

During exercise, McGonigal explains, our brains release neurotransmitters, in particular dopamine and endocannabinoids, that can generate a natural high similar to that of cannabis, or marijuana.

"Many of the effects of cannabis are consistent with descriptions of exercise-induced highs, including the sudden disappearance of worries or stress, a reduction in pain, the slowing of time and a heightening of the senses," she writes.

Shots - Health News

Fresh starts, guilty pleasures and other pro tips for sticking to good habits.

And while exercise activates the same channels of the brain's reward system that addictive drugs do, she explains, it does so "in a way that has the complete opposite effect on your capacity to enjoy life."

Exactly how it all works isn't fully understood.

"But the basic idea is that your brain will have a more robust response to everyday pleasures," she says, "whether it's your child smiling at you, or the taste of food or your enjoyment of looking at something beautiful — and that's the exact opposite effect of addiction."

2) Become a "more social version of yourself"

In a chapter on the collective joy of exercise, McGonigal explains how endorphins — another type of neurotransmitters released during sustained physical activity — help bond us to others. It's a connection, she writes, that "can be experienced anytime and anywhere people gather to move in unison," be it during the flow of yoga class, during the synchronicity of team rowing, while running with friends or while practicing tai chi with others.

Soul Line Dancing: Come For The Fitness. Stay For The Friendships

And it also helps explain why those with whom we participate on teams or share fitness friendships often feel like family, she says. Endorphins help strengthen ties to individuals we're not related to, which helps us build extended families and important social networks that help stave off loneliness and social isolation.

Of course, humans can build bonds through sedentary activities as well, McGonigal says.

"But there's something about getting your heart rate up a little bit and using your muscles that creates that brain state that makes you more willing to trust others — that enhances the pleasure you get from interacting with others that often makes you this more social version of yourself," she says.

3) Help with depression

In a section on "green exercise," McGonigal discusses the positive shifts in mood and outlook reported by those who exercise in nature.

"It actually alters what's happening in your brain in a way that looks really similar to meditation," she says. "People report feeling connected to all of life ... and they feel more hopeful about life itself."

Indeed, an Austrian study McGonigal cites found that among people who had previously attempted suicide, the addition of mountain hiking to their standard medical treatment reduced suicidal thinking and hopelessness.

From Couch Potato To Fitness Buff: How I Learned To Love Exercise

McGonigal says she heard many similar stories among those she interviewed for the book: "So many people who struggle with anxiety, grief or depression find a kind of relief in being active in nature that they don't find any other way."

4) Reveal hidden strength

Even for those who don't struggle with mental or physical illness, adopting a regular exercise routine can provide powerful transformation. McGonigal shares stories of several women who overcame limiting beliefs through exercise to reveal new, more powerful selves.

"If there is a voice in your head saying, 'You're too old, too awkward, too big, too broken, too weak,' physical sensations from movement can provide a compelling counterargument," McGonigal writes. "Even deeply held beliefs about ourselves can be challenged by direct, physical experiences, as new sensations overtake old memories and stories."

5) A boost for the brain

McGonigal offers insights drawn from research into ultraendurance athletes and how they survive mentally and physically grueling events designed to last six or more hours.

When researchers at the Berlin-based Center for Space Medicine and Extreme Environments measured the blood of ultraendurance athletes, they found high levels a family of proteins called myokines, known to help the body burn fat as fuel, to act as natural antidepressants and to provide a possible shield against cognitive decline.

But as she reports, you don't need to be a superathlete to experience the benefits of myokines. McGonigal cites a 2018 study that identified 35 of these proteins released by the quadriceps muscles during just one hour of bike riding.

Emerging research, she says, suggests that when exercised, your muscles become "basically a pharmacy for your physical and mental health."

"If you are willing to move," she writes, "your muscles will give you hope. Your brain will orchestrate pleasure. And your entire physiology will adjust to help you find the energy, purpose and courage you need to keep going."

- social connection

- mental health

- Systematic review update

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2023

The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: a systematic review and the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model

- Narelle Eather ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6320-4540 1 , 2 ,

- Levi Wade ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4007-5336 1 , 3 ,

- Aurélie Pankowiak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0178-513X 4 &

- Rochelle Eime ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8614-2813 4 , 5

Systematic Reviews volume 12 , Article number: 102 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

91k Accesses

37 Citations

332 Altmetric

Metrics details

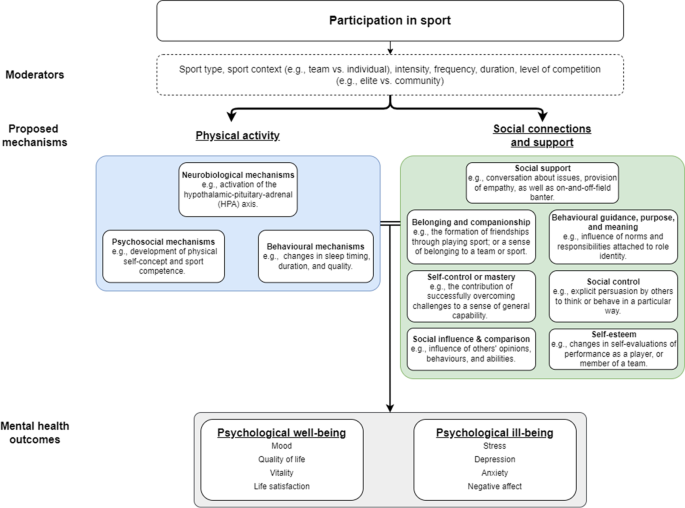

Sport is a subset of physical activity that can be particularly beneficial for short-and-long-term physical and mental health, and social outcomes in adults. This study presents the results of an updated systematic review of the mental health and social outcomes of community and elite-level sport participation for adults. The findings have informed the development of the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model for adults.

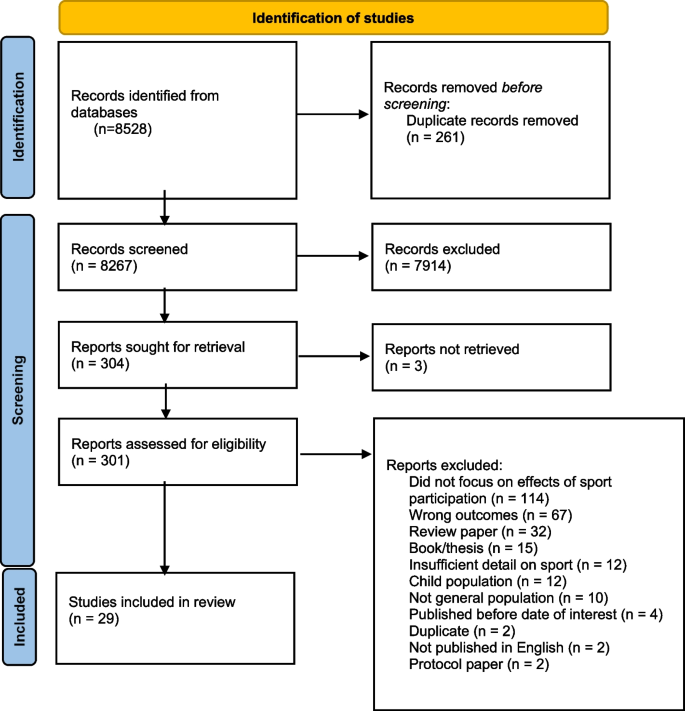

Nine electronic databases were searched, with studies published between 2012 and March 2020 screened for inclusion. Eligible qualitative and quantitative studies reported on the relationship between sport participation and mental health and/or social outcomes in adult populations. Risk of bias (ROB) was determined using the Quality Assessment Tool (quantitative studies) or Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (qualitative studies).

The search strategy located 8528 articles, of which, 29 involving adults 18–84 years were included for analysis. Data was extracted for demographics, methodology, and study outcomes, and results presented according to study design. The evidence indicates that participation in sport (community and elite) is related to better mental health, including improved psychological well-being (for example, higher self-esteem and life satisfaction) and lower psychological ill-being (for example, reduced levels of depression, anxiety, and stress), and improved social outcomes (for example, improved self-control, pro-social behavior, interpersonal communication, and fostering a sense of belonging). Overall, adults participating in team sport had more favorable health outcomes than those participating in individual sport, and those participating in sports more often generally report the greatest benefits; however, some evidence suggests that adults in elite sport may experience higher levels of psychological distress. Low ROB was observed for qualitative studies, but quantitative studies demonstrated inconsistencies in methodological quality.

Conclusions

The findings of this review confirm that participation in sport of any form (team or individual) is beneficial for improving mental health and social outcomes amongst adults. Team sports, however, may provide more potent and additional benefits for mental and social outcomes across adulthood. This review also provides preliminary evidence for the Mental Health through Sport model, though further experimental and longitudinal evidence is needed to establish the mechanisms responsible for sports effect on mental health and moderators of intervention effects. Additional qualitative work is also required to gain a better understanding of the relationship between specific elements of the sporting environment and mental health and social outcomes in adult participants.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The organizational structure of sport and the performance demands characteristic of sport training and competition provide a unique opportunity for participants to engage in health-enhancing physical activity of varied intensity, duration, and mode; and the opportunity to do so with other people as part of a team and/or club. Participation in individual and team sports have shown to be beneficial to physical, social, psychological, and cognitive health outcomes [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Often, the social and mental health benefits facilitated through participation in sport exceed those achieved through participation in other leisure-time or recreational activities [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Notably, these benefits are observed across different sports and sub-populations (including youth, adults, older adults, males, and females) [ 11 ]. However, the evidence regarding sports participation at the elite level is limited, with available research indicating that elite athletes may be more susceptible to mental health problems, potentially due to the intense mental and physical demands placed on elite athletes [ 12 ].

Participation in sport varies across the lifespan, with children representing the largest cohort to engage in organized community sport [ 13 ]. Across adolescence and into young adulthood, dropout from organized sport is common, and especially for females [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], and adults are shifting from organized sports towards leisure and fitness activities, where individual activities (including swimming, walking, and cycling) are the most popular [ 13 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Despite the general decline in sport participation with age [ 13 ], the most recent (pre-COVID) global data highlights that a range of organized team sports (such as, basketball, netball volleyball, and tennis) continue to rank highly amongst adult sport participants, with soccer remaining a popular choice across all regions of the world [ 13 ]. It is encouraging many adults continue to participate in sport and physical activities throughout their lives; however, high rates of dropout in youth sport and non-participation amongst adults means that many individuals may be missing the opportunity to reap the potential health benefits associated with participation in sport.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health refers to a state of well-being and effective functioning in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, is resilient to the stresses of life, and is able to make a positive contribution to his or her community [ 20 ]. Mental health covers three main components, including psychological, emotional and social health [ 21 ]. Further, psychological health has two distinct indicators, psychological well-being (e.g., self-esteem and quality of life) and psychological ill-being (e.g., pre-clinical psychological states such as psychological difficulties and high levels of stress) [ 22 ]. Emotional well-being describes how an individual feels about themselves (including life satisfaction, interest in life, loneliness, and happiness); and social well–being includes an individual’s contribution to, and integration in society [ 23 ].

Mental illnesses are common among adults and incidence rates have remained consistently high over the past 25 years (~ 10% of people affected globally) [ 24 ]. Recent statistics released by the World Health Organization indicate that depression and anxiety are the most common mental disorders, affecting an estimated 264 million people, ranking as one of the main causes of disability worldwide [ 25 , 26 ]. Specific elements of social health, including high levels of isolation and loneliness among adults, are now also considered a serious public health concern due to the strong connections with ill-health [ 27 ]. Participation in sport has shown to positively impact mental and social health status, with a previous systematic review by Eime et al. (2013) indicated that sports participation was associated with lower levels of perceived stress, and improved vitality, social functioning, mental health, and life satisfaction [ 1 ]. Based on their findings, the authors developed a conceptual model (health through sport) depicting the relationship between determinants of adult sports participation and physical, psychological, and social health benefits of participation. In support of Eime’s review findings, Malm and colleagues (2019) recently described how sport aids in preventing or alleviating mental illness, including depressive symptoms and anxiety or stress-related disease [ 7 ]. Andersen (2019) also highlighted that team sports participation is associated with decreased rates of depression and anxiety [ 11 ]. In general, these reviews report stronger effects for sports participation compared to other types of physical activity, and a dose–response relationship between sports participation and mental health outcomes (i.e., higher volume and/or intensity of participation being associated with greater health benefits) when adults participate in sports they enjoy and choose [ 1 , 7 ]. Sport is typically more social than other forms of physical activity, including enhanced social connectedness, social support, peer bonding, and club support, which may provide some explanation as to why sport appears to be especially beneficial to mental and social health [ 28 ].

Thoits (2011) proposed several potential mechanisms through which social relationships and social support improve physical and psychological well-being [ 29 ]; however, these mechanisms have yet to be explored in the context of sports participation at any level in adults. The identification of the mechanisms responsible for such effects may direct future research in this area and help inform future policy and practice in the delivery of sport to enhance mental health and social outcomes amongst adult participants. Therefore, the primary objective of this review was to examine and synthesize all research findings regarding the relationship between sports participation, mental health and social outcomes at the community and elite level in adults. Based on the review findings, the secondary objective was to develop the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model.

This review has been registered in the PROSPERO systematic review database and assigned the identifier: CRD42020185412. The conduct and reporting of this systematic review also follows the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 30 ] (PRISMA flow diagram and PRISMA Checklist available in supplementary files ). This review is an update of a previous review of the same topic [ 31 ], published in 2012.

Identification of studies

Nine electronic databases (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Informit, Medline, PsychINFO, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, Scopus, and SPORTDiscus) were systematically searched for relevant records published from 2012 to March 10, 2020. The following key terms were developed by all members of the research team (and guided by previous reviews) and entered into these databases by author LW: sport* AND health AND value OR benefit* OR effect* OR outcome* OR impact* AND psych* OR depress* OR stress OR anxiety OR happiness OR mood OR ‘quality of life’ OR ‘social health’ OR ‘social relation*’ OR well* OR ‘social connect*’ OR ‘social functioning’ OR ‘life satisfac*’ OR ‘mental health’ OR social OR sociolog* OR affect* OR enjoy* OR fun. Where possible, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were also used.

Criteria for inclusion/exclusion

The titles of studies identified using this method were screened by LW. Abstract and full text of the articles were reviewed independently by LW and NE. To be included in the current review, each study needed to meet each of the following criteria: (1) published in English from 2012 to 2020; (2) full-text available online; (3) original research or report published in a peer-reviewed journal; (4) provides data on the psychological or social effects of participation in sport (with sport defined as a subset of exercise that can be undertaken individually or as a part of a team, where participants adhere to a common set of rules or expectations, and a defined goal exists); (5) the population of interest were adults (18 years and older) and were apparently healthy. All papers retrieved in the initial search were assessed for eligibility by title and abstract. In cases where a study could not be included or excluded via their title and abstract, the full text of the article was reviewed independently by two of the authors.

Data extraction

For the included studies, the following data was extracted independently by LW and checked by NE using a customized Google Docs spreadsheet: author name, year of publication, country, study design, aim, type of sport (e.g., tennis, hockey, team, individual), study conditions/comparisons, sample size, where participants were recruited from, mean age of participants, measure of sports participation, measure of physical activity, psychological and/or social outcome/s, measure of psychological and/or social outcome/s, statistical method of analysis, changes in physical activity or sports participation, and the psychological and/or social results.

Risk of bias (ROB) assessment

A risk of bias was performed by LW and AP independently using the ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies’ OR the ‘Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies’ for the included quantitative studies, and the ‘Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist for the included qualitative studies [ 32 , 33 ]. Any discrepancies in the ROB assessments were discussed between the two reviewers, and a consensus reached.

The search yielded 8528 studies, with a total of 29 studies included in the systematic review (Fig. 1 ). Tables 1 and 2 provide a summary of the included studies. The research included adults from 18 to 84 years old, with most of the evidence coming from studies targeting young adults (18–25 years). Study samples ranged from 14 to 131, 962, with the most reported psychological outcomes being self-rated mental health ( n = 5) and depression ( n = 5). Most studies did not investigate or report the link between a particular sport and a specific mental health or social outcome; instead, the authors’ focused on comparing the impact of sport to physical activity, and/or individual sports compared to team sports. The results of this review are summarized in the following section, with findings presented by study design (cross-sectional, experimental, and longitudinal).

Flow of studies through the review process

Effects of sports participation on psychological well-being, ill-being, and social outcomes

Cross-sectional evidence.

This review included 14 studies reporting on the cross-sectional relationship between sports participation and psychological and/or social outcomes. Sample sizes range from n = 414 to n = 131,962 with a total of n = 239,394 adults included across the cross-sectional studies.

The cross-sectional evidence generally supports that participation in sport, and especially team sports, is associated with greater mental health and psychological wellbeing in adults compared to non-participants [ 36 , 59 ]; and that higher frequency of sports participation and/or sport played at a higher level of competition, are also linked to lower levels of mental distress in adults . This was not the case for one specific study involving ice hockey players aged 35 and over, with Kitchen and Chowhan (2016) Kitchen and Chowhan (2016) reporting no relationship between participation in ice hockey and either mental health, or perceived life stress [ 54 ]. There is also some evidence to support that previous participation in sports (e.g., during childhood or young adulthood) is linked to better mental health outcomes later in life, including improved mental well-being and lower mental distress [ 59 ], even after controlling for age and current physical activity.

Compared to published community data for adults, elite or high-performance adult athletes demonstrated higher levels of body satisfaction, self-esteem, and overall life satisfaction [ 39 ]; and reported reduced tendency to respond to distress with anger and depression. However, rates of psychological distress were higher in the elite sport cohort (compared to community norms), with nearly 1 in 5 athletes reporting ‘high to very high’ distress, and 1 in 3 reporting poor mental health symptoms at a level warranting treatment by a health professional in one study ( n = 749) [ 39 ].