Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 78, Issue 10

- Intergenerational transmission of health inequalities: research agenda for a life course approach to socioeconomic inequalities in health

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6090-4376 Tanja A J Houweling 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7034-1922 Ilona Grünberger 2

- 1 Department of Public Health , Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam , Rotterdam , The Netherlands

- 2 Department of Public Health Sciences , Stockholm University , Stockholm , Sweden

- Correspondence to Dr Tanja A J Houweling, Department of Public Health, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands; a.j.houweling{at}erasmusmc.nl

Explanations for socioeconomic inequalities in adult health are usually sought in behaviours and environments in adulthood. Yet, there is compelling evidence that the first two decades of life contribute substantially to both adult socioeconomic position (SEP) and adult health. This has implications for explanatory health inequalities research.

We propose an analytical framework to advance research on the intergenerational transmission of health inequalities, that is, on intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic and associated health (dis)advantages at the family level, and its contribution to health inequalities at the population level. The framework distinguishes three transmission pathways: (1) intergenerational transmission of SEP, with effects on offspring health fully mediated by offspring SEP; (2) intergenerational transmission of health problems affecting SEP and (3) intergenerational transmission of both SEP and health, without a causal relationship between offspring adult SEP and health. We describe areas for future research along this framework and discuss the challenges and opportunities to advance this field.

- Health inequalities

- Life course epidemiology

- CHILD HEALTH

- PUBLIC HEALTH

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2022-220163

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

A framework for research

Traditionally, explanations for socioeconomic inequalities in adult health are sought in behaviours and environments in adulthood. 1 Figure 1 visualises this relationship between adult socioeconomic position (SEP) and adult health. In this framework, SEP is causally related to proximal health determinants, such as smoking, and health outcomes in adulthood; and there is some reverse causation between health (determinants) and SEP (also called ‘selection’).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Traditional framework for explaining socioeconomic health inequalities. SEP, socioeconomic position.

Yet, from a broad range of disciplines, there is evidence that the early years of life contribute substantially to both adult SEP and adult health. In a companion paper, we have described how socioeconomic and health (dis)advantages are intergenerationally transmitted at the family level, and contribute to the persistence of socioeconomic health inequalities at the population level. 2 We found evidence that broadly the same mechanisms, in the fetal and postnatal environment, shape both adult SEP and adult health. This has implications for explanatory research on socioeconomic inequalities in health.

Figure 2 provides a framework for studying socioeconomic health inequalities from an intergenerational perspective. The pathways through which health inequalities are intergenerationally transmitted, can be grouped into three models.

Conceptual framework for the intergenerational transmission of health inequalities. Three models of intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic health inequalities: (1) socioeconomic transmission: intergenerational transmission of SEP, combined with an effect of offspring adult SEP on health; (2) health transmission: intergenerational transmission of parental health problems that affect SEP; (3) sociobiological transmission: parental SEP influences both offspring SEP and offspring health (determinants). SEP, socioeconomic position.

In the first model (socioeconomic transmission, red arrows), the SEP-health link is transmitted across generations as a result of intergenerational transmission of SEP. 3 Intergenerational transmission of SEP occurs through (in)direct transfers (eg, of wealth), and via the fetal and postnatal environment—through the influence of parental SEP, parental proximal health determinants and parental health outcomes associated with SEP. As long as offspring adult SEP influences health, there needs to be no direct causal relationship between parental SEP and offspring health (determinants) for health inequalities to be intergenerationally transmitted. In this model, the relationship between parental SEP and offspring health, is fully mediated by offspring SEP. Consequently, statistical adjustment for offspring SEP would lead to severe underestimation of the contribution of intergenerational transmission to adult health inequalities.

In the second model (health transmission, blue arrows), the SEP-health link is transmitted across generations through intergenerational transmission of health problems that affect SEP, such as mental health problems. There is substantial evidence that such parental problems affect child development and well-being, but there is a paucity of evidence about their role in explaining offspring adult health inequalities.

The third model (sociobiological transmission, green arrows) consists of a purely intergenerational causal effect of SEP on adult health. Here, parental SEP influences both offspring SEP and offspring health (determinants), without a causal relationship between offspring adult SEP and health. 3 This is sometimes called indirect selection. The fetal environment, the learning and psychosocial environment, and childhood and adolescent socialisation, affect offspring adult SEP and health by influencing child and adolescent cognitive, socialemotional, and physical health and development, and patterns of beliefs, values and behavioural habits.

In practice, SEP and health are causally related within and across generations—their contributions varying with the health outcome studied—such that the three above models reinforce each other. The relative importance of the three models, and how this varies over historical time and across societal contexts, remains largely unknown. Yet, this is crucial information for designing interventions and determining the appropriate timing of policies to reduce health inequalities. 4

Research agenda based on the framework

Our framework can be used as basis for asking relevant questions to advance this field, including questions around how policies and other societal conditions affect the different pathways in this framework.

Intergenerational transmission of SEP

A first set of questions relates to the intergenerational transmission of SEP. What proportion of adult health inequalities is attributable to the effect of parental SEP on offspring SEP? A rough calculation can be analogous to that of population attributable fractions. So, with what percentage would health inequalities reduce if offspring of low SEP parents had the same educational (wealth, income) distribution as offspring of high SEP parents? Next, what is the impact of structural determinants of intergenerational social mobility, for example, social protection policies and education systems, on adult health inequalities? Intergenerational social mobility is larger in some cohorts and countries than in others, 5 arguably affecting the proportion of health inequalities attributable to intergenerational SEP persistence. This suggests room for policy-making, by ensuring that all children can develop to their full potential, irrespective of parental SEP. It also suggests the need to better understand these structural factors and their political and historical determinants.

The effect of parental and offspring SEP on offspring health

A second set of questions relates to the effect of parental and offspring SEP on offspring health. Does parental SEP have an independent effect on offspring adult health, that is, not mediated by offspring adult SEP? 6–8 To what extent is the health effect of offspring adult SEP explained by parental SEP? What is the relative importance of the independent effects of offspring and parental SEP? Three methodological problems complicate answering these questions. The first is intermediate confounding. Important determinants of both offspring SEP and offspring health—including cognitive ability, socialemotional well-being and habits—are strongly influenced by parental SEP. When examining the independent health effects of offspring SEP, these factors, shaped in early life, could be important confounders. 9 The second problem is mediator-outcome confounding (collider bias). Independent effects of parental and offspring SEP are mostly examined in discordant parent-offspring pairs, that is, in cases of intergenerational upward or downward mobility. 6–8 But these may be selective groups. Analyses should, therefore, be adjusted for factors influencing both intergenerational mobility and offspring adult health. Third, intergenerational social mobility may have health effects itself, requiring the inclusion of interaction terms between parental SEP and offspring adult SEP. Modern causal mediation analyses can partly address these problems and be used to decompose the effect of parental SEP on offspring health into direct effects, and indirect effects via offspring SEP, even in the presence of interaction. 10 Also, structured approaches to compare life course models have been applied to these questions. 4 11 Howe et al have linked causal mediation analysis to a structured life course approach. 3 A next step would be to address intermediate confounding and mediator-outcome confounding in such models.

While the above models and mechanisms could be seen as acting within relatively stable social and policy contexts, another way forward would be through research on the health effects of exogenous changes in parental and offspring adult SEP, for example, income changes due to new social security policies. A possible strategy would be to focus on determinants of adult health that are largely shaped in early life—including cognitive ability, executive functions, social-emotional well-being, habits and beliefs 12 13 —and examine to which extent these explain adult health inequalities. 14 Such a strategy could also include research on (1) stability of the association between SEP on the one hand, and cognitive ability, executive functions, behavioural habits and beliefs on the other, throughout childhood, adolescence and beyond 15 ; (2) their contribution to inequalities in health behaviours in adulthood and (3) and their interaction with the environment in both childhood and adulthood (eg, Are changes in school policies affecting children from disadvantaged backgrounds disproportionately? Is a health promoting environment more important for individuals with lower executive functions?)

Intergenerational transmission of health problems associated with SEP

A third set of questions relate to the intergenerational transmission of health problems that are associated with SEP. What is the contribution of parental health problems, such as mental health problems, which affect both parental SEP and their offspring’s development and life course outcomes, to the intergenerational transmission of health inequalities? And what is the relative importance of fetal and postnatal environmental pathways to this transmission? A first step would be to describe what proportion of parents with low SEP suffer from such health problems. In social epidemiological research, low SEP tends to be treated as a uniform category. 16 Unpacking this to understand the complex set of problems underlying low SEP, and how these problems cluster and interact, and are transmitted intergenerationally in different societal and policy contexts, is important, also for policy-making.

The first two decades of life, from the prenatal period to early adulthood, play an important role in the development of socioeconomic inequalities in adult health and help explain the persistence of these inequalities in welfare states. It is time to give more attention to these early years in research on and policies to tackle adult health inequalities. It is important to recognise that SEP, and many determinants of health and health behaviour, are formed early in life. SEP and health determinants that are shaped in these early years—including cognitive development, executive functions, beliefs and habits—should not be taken as a given. Rather, understanding their development and intergenerational transmission should be squarely rooted within health inequalities research, thereby providing a basis for preventive policies.

Methodological advances and the coming of age of many birth cohorts provide opportunities for empirical research across multiple generations. We have provided a framework to advance this research field. It will require interdisciplinary research to not only understand the complexities of the physiological processes that lead to intergenerational transmission of health inequalities, but also the social complexities that often remain hidden behind the term ‘SEP’. Importantly, our framework also describes new opportunities for action. There is a lot to be gained.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Johan P. Mackenbach for his comments on an outline of this paper and for helpful discussions during preparation of the International Symposium on the Intergenerational Transmission of Health Inequalities that TAJH organised with him on 25 October 2018 –26 October 2018, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. We thank presenters and participants at this symposium for their presentations and their contributions to the discussions.

- Mackenbach JP

- Houweling TAJ ,

- Grünberger I

- Macdonald-Wallis C , et al

- Mishra GD ,

- Goodman A , et al

- Galobardes B ,

- Hossin MZ ,

- Falkstedt D

- Loucks EB ,

- Rogers ML , et al

- VanderWeele TJ

- Black S , et al

- Early Child Development Knowledge Network of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health

- Sehmi R , et al

- Hemmingsson T ,

- v Essen J ,

- Melin B , et al

- Hackman DA ,

- Evans GW , et al

X @TanjaHouweling

Contributors TAJH conceived of and drafted the manuscript. IG critically reviewed the draft manuscript and contributed to revisions. Both authors have approved of the final manuscript before submission.

Funding TAJH is supported by NWO grant number NWA.1238.18.001 and though a grant awarded by the Norwegian Research Council (project number 288638) to the Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research (CHAIN) at the Norwegian University for Science and Technology (NTNU). The International Symposium on the Intergenerational Transmission of Health Inequalities was financially supported by the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences (KNAW) and a EUR Research Excellence initiative grant obtained by TAJH. TAJH is also member of a ZonMW funded project on socioeconomic inequalities in child development (grant number 531003013). IG is supported by a grant from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE project number 2018-00211).

Disclaimer The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the articles; and in the decision to submit it for publication.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Create new account

- Reset your password

- Translation

- Alternative Standpoint

- HT Parekh Finance Column

- Law and Society

- Strategic Affairs

- Perspectives

- Special Articles

- The Economic Weekly (1949–1965)

- Economic and Political Weekly

- Open Access

- Notes for contributors

- Style Sheet

- Track Your Submission

- Resource Kits

- Discussion Maps

- Interventions

- Research Radio

Advanced Search

A + | A | A -

Violence against Women in India

Understanding trends in the extent of violence against women can be helpful in challenging violence against women and gender inequality. In this paper, we compare the incidence of violence, as measured in the National Family Health Surveys, to the reporting of violence, as compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau. We also shed light on heterogeneity in incidence and reporting across India’s states. We find that violence against women is common, that most violence against women is not reported to the police, that violence by husbands is less likely to be reported than violence by others, and that the reporting of violence has not improved over the last decade and a half. These concerning findings highlight the urgent need for social and legal interventions to reduce violence against women, and to improve its reporting.

The authors would like to thank Vipul Paikra for helpful research assistance.

Sexual and physical violence against women is one of the clearest and most detrimental manifestations of gender inequa lity. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals aim at “eliminating violence against women and girls” (UNWomen 2022). And violence against women remains one of the core concerns of movements against patriarchy in India and globally (Kannabiran and Menon 2007). Despite this recogn ition, public discussions on violence against women in India are c onstrained by the lack of reliable information on the magnitude of violence against women, the extent to which cases are reported to the police, or trends in incidence and reporting (Bhattacharya 2013; Gupta 2014; Rukmini 2021).

Dear Reader,

To continue reading, become a subscriber.

Explore our attractive subscription offers.

To gain instant access to this article (download).

(Readers in India)

(Readers outside India)

Your Support will ensure EPW’s financial viability and sustainability.

The EPW produces independent and public-spirited scholarship and analyses of contemporary affairs every week. EPW is one of the few publications that keep alive the spirit of intellectual inquiry in the Indian media.

Often described as a publication with a “social conscience,” EPW has never shied away from taking strong editorial positions. Our publication is free from political pressure, or commercial interests. Our editorial independence is our pride.

We rely on your support to continue the endeavour of highlighting the challenges faced by the disadvantaged, writings from the margins, and scholarship on the most pertinent issues that concern contemporary Indian society.

Every contribution is valuable for our future.

- About Engage

- For Contributors

- About Open Access

- Opportunities

Term & Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Circulation

- Refund and Cancellation

- User Registration

- Delivery Policy

Advertisement

- Why Advertise in EPW?

- Advertisement Tariffs

Connect with us

320-322, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai, India 400 013

Phone: +91-22-40638282 | Email: Editorial - [email protected] | Subscription - [email protected] | Advertisement - [email protected]

Designed, developed and maintained by Yodasoft Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

September National Health Observances: Healthy Aging, Sickle Cell Disease, and More

Each month, we feature select National Health Observances (NHOs) that align with our priorities for improving health across the nation. In September, we’re raising awareness about healthy aging, sickle cell disease, substance use recovery, and HIV/AIDS.

Below, you’ll find resources to help you spread the word about these NHOs with your audiences.

- Healthy Aging Month Each September, we celebrate Healthy Aging Month to promote ways people can stay healthy as they age. Explore our healthy aging resources , bookmark the Healthy People 2030 and Older Adults page , share our Move Your Way® materials for older adults , and check out the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report . You can also share resources related to healthy aging from the National Institute on Aging — and register for the 2024 National Healthy Aging Symposium to hear from experts on innovations to improve the health and well-being of older adults.

- National Recovery Month The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) sponsors National Recovery Month to raise awareness about mental health and addiction recovery. Share our MyHealthfinder resources on substance use and misuse — and be sure to check out Healthy People 2030’s evidence-based resources related to drug and alcohol use .

- National Sickle Cell Awareness Month National Sickle Cell Awareness Month is a time to raise awareness and support people living with sickle cell disease. Help your community learn about sickle cell disease by sharing these resources from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) . You can also encourage new and expecting parents to learn about screening their newborn baby for sickle cell . And be sure to view our Healthy People 2030 objectives on improving health for people who have blood disorders .

- National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day (September 18) On September 18, we celebrate HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day to encourage older adults to get tested for HIV. Share CDC’s Let’s Stop HIV Together campaign to help promote HIV testing, prevention, and treatment. MyHealthfinder also has information for consumers about getting tested for HIV and actionable questions for the doctor about HIV testing . Finally, share these evidence-based resources on sexually transmitted infections from Healthy People 2030.

- National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day (September 27) National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day on September 27 highlights the impact of HIV on gay and bisexual men and promotes strategies to encourage testing. Get involved by sharing CDC’s social media toolkit and HIV information to encourage men to get tested — and share our MyHealthfinder resources to help people get tested for HIV and talk with their doctor about testing .

We hope you’ll join us in promoting these important NHOs with your networks to help improve health across the nation!

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Why a health...

Why a health inequalities white paper is still so vital and should not be scrapped

Linked news.

Health inequalities: Government must not abandon white paper, health leaders urge

- Related content

- Peer review

- Layla McCay , director of policy

- NHS Confederation

Health inequalities across the country have been widening for many years, and if they had ever not been obvious before, the covid-19 pandemic served to shine a spotlight on the health inequalities which are so keenly apparent in so many communities across the UK.

A significant and growing gap in life expectancy for people living in areas with the highest and lowest levels of deprivation means there is now an urgent need to create opportunities for health and care systems to drive improvements in population health outcomes at pace. So, if the rumours are to be believed and the new secretary of state for health and social care has decided to shelve the work of her predecessor and abandon the long-awaited health inequalities white paper this will deal a huge blow to the health and life chances of millions of people across the country.

The newly created Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) provide a fresh opportunity for central government and local leaders to share power locally in a flexible and dynamic way which, over time, should really help reduce inequalities in health outcomes. Through integrated care partnerships (ICPs), local leaders can embrace community power and they will have a mechanism to develop services according to the priorities of their local communities.

To improve population health, NHS, local government and social care leaders alike are urging the government not to perform such a significant and damaging volte-face, but to build on existing knowledge of what works and to consider holistically the social, economic, and commercial determinants of health when addressing inequalities. Their view is that a system-wide approach is fundamental and breaking down siloed ways of working within local systems will be crucial.

They say that the government must commit to this white paper which should consider action in four key areas to really shift the dial and reduce health inequalities once and for all.

First, leaders want to see health equity in all policies. Up to 80 per cent of what affects health—both physical and mental—is from outside of the health system, so the impact of a white paper that fails to outline a cross-government approach that looks beyond the remit of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), will be drastically constrained.

The need to adopt a cross-Whitehall approach to reduce health inequalities is widely accepted. The NHS Confederation, as a member of the Inequalities in Health Alliance, a coalition of over 150 healthcare organisations, is calling for a cross-government strategy to reduce inequalities. They have written to the new Secretary of State urging her to keep the commitment to publish it before the end of this year. A health equity in all policies approach recommends action beyond the health sector, taking into account all the drivers of ill health and promoting actions that contribute to good health and wellbeing.

Secondly, leaders want prevention to be incentivised so that local systems can allocate resources according to health need and deprivation. This will require the government to make use of the structural and regulatory levers at its disposal, such as taxes and levies, to create a society where the healthy choice is the easy choice for everyone.

Last year’s Government Spending Review which failed to commit to a real-terms increase in the public health grant and soaring inflation rates which currently stand at 9 per cent, mean the Spending Review’s commitments represent a significant real-terms cut in funding. The white paper must reinstate real-terms funding increases at the level seen before 2015.

Thirdly inclusive innovation, integration, and access will be key to driving down national and local inequalities in health. The covid-19 pandemic showed that innovation in health and care services could be delivered including remote consultation. However, while very positive, there is a real risk that without concerted action to ensure these new approaches reach the country’s most deprived areas and communities, they will exacerbate inequalities.

The white paper is needed and must set out funding proposals to close the digital gap, and a strategy for the provision of health services on the high street. A plan is also needed for a population health management approach to general practice data to enable primary prevention to begin in primary care.

Equitable innovation will mean that communities are involved and engaged in defining what it looks like and that results are monitored and evaluated over the long term. Deep partnership working with the voluntary, community, and social enterprise sector will also provide valuable links into those communities.

Finally, there needs to be real concerted action on the cost-of-living crisis for communities.

A record number of working families now find themselves living in poverty. Government support must be targeted towards those who need it most in our communities. For health and care staff, this means a fully funded, generous pay rise for healthcare staff on the lowest pay, and a national care workers’ minimum wage of £10.50. The white paper must also encourage a flexible approach to the Apprenticeship Levy, using widening participation principles to enable more people from disadvantaged or excluded communities to get into work.

With concerted action it is possible to make real inroads in tackling the increasingly disparate health outcomes experienced across the country to create the conditions for a healthier population, with no-one left behind.

Moving from silo to system in our approach to population health outcome improvement will not just allow local health and care leaders to mind the health inequity gap but will engage and empower them to mend and reduce it.

Competing interests: none declared.

Provenance and peer review: not commissioned, not peer reviewed.

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Income, Poverty, and Health Inequality

- 1 Chief population health officer of New York City Health + Hospitals, and clinical associate professor of population health and medicine at the New York University School of Medicine

The health of people with low incomes historically has been a driver of public health advances in the United States. For example, in New York City, cholera deaths during outbreaks in 1832 and 1854 concentrated among the poor helped push forward the Metropolitan Health Law, which allowed for regulation of sanitary conditions in the city. The law was an exemplar for other municipalities across the United States, saving countless lives during subsequent cholera epidemics as well as from typhus, dysentery, and smallpox.

Health inequality persists today, though our public health response—our modern Metropolitan Health Laws—must address more insidious causes and conditions of illness. There is a robust literature linking income inequality to health disparities —and thus widening income inequality is cause for concern. US Census data show a steady increase in summary measures of income inequality over the past 50 years. The association between income and life expectancy, already well established, was detailed in a landmark 2016 JAMA study by Raj Chetty, PhD, of Stanford University, and colleagues. This study found a gap in life expectancy of about 15 years for men and 10 years for women when comparing the most affluent 1% of individuals with the poorest 1%. To put this into perspective, the 10-year life expectancy difference for women is equal to the decrement in longevity from a lifetime of smoking.

Probing the Income-Health Relationship

In an editorial that accompanied the article by Chetty et al, Angus Deaton, PhD, of Princeton University, commented on the study’s geographical findings: “It is as if the top income percentiles belong to one world of elite, wealthy US adults, whereas the bottom income percentiles each belong to separate worlds of poverty, each unhappy and unhealthy in its own way.” Prior research had tried to identify these separate worlds, describing “ Eight Americas ” defined by sociodemographic characteristics, such as low-income white people in Appalachia and the Mississippi Valley, Western Native Americans, and Southern low-income rural black people. To improve health, interventions may need to account for starkly different lived experiences across different geographic contexts.

Educational attainment, sex, and race interact with and complicate the income-health relationship. Two additional dimensions add complexity: thinking beyond income to wealth and thinking beyond mortality to morbidity. Wealth refers to the total value of assets (and debts) possessed by an individual, not just the flow of money defined as income. Wealth is even more unequally divided than income : while the top 10% of the income distribution received a little more than half of all income, the top 10% of the wealth distribution held more than three-quarters of all wealth. This matters because it is one way that inequities persist over time —through, for instance, legacy effects of Jim Crow laws or discriminatory housing policy that affect family wealth and health over generations .

Studies on inequality and mortality may garner the most attention, but disparities in morbidity and quality of life are also evident. Low-income adults are more than 3 times as likely to have limitations with routine activities (like eating, bathing, and dressing) due to chronic illness, compared with more affluent individuals. Children living in poverty are more likely to have risk factors such as obesity and elevated blood lead levels, affecting their future health prospects.

Inequality or Inequity?

Is it the role of physicians and other health professionals to address poverty? Is it a “modifiable” risk factor, or should we focus on more proximate causes of illness, such as health behaviors? Our answers to these questions determine whether wealth gradients lead only to health inequality—or whether they contribute to health inequity , which is inequality that is avoidable and unfair.

Two arguments favor paying attention to income and wealth distributions as part of advancing health equity. First, health care spending—the realm of medical professionals—can worsen income inequality, at both individual and systemic levels. Individually, poor people have to spend a much greater proportion of their income on health care than richer people do. In 2014, medical outlays lowered the median income for the poorest decile of US individuals by 47.6% vs 2.7% for the wealthiest decile. Systemically, medical spending can crowd out other government spending on social services , drawing resources away from education and environmental improvement, for example. Taken together, this supports the case that “first do no harm” must extend to the financial impact of delivering health care. Clinicians who care about the social determinants of health must also pay heed to the cost (and opportunity cost) of health care.

Second, we are in a period when declines in key public health indicators may be wrought by policies that ostensibly have little to do with health—such as tax policy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that average life expectancy decreased for the second year in a row in 2016. But mean mortality changes may obscure the full picture , which is more about increasing mortality being concentrated in lower-income groups. Meanwhile, the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is likely to exacerbate income inequality. This is particularly true if the tax cuts trigger cuts in government spending , as Republican leaders have signaled. Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as food stamps) are 2 programs for low-income individuals that are likely to be targeted for cuts. Even if Medicare and Social Security are spared, life expectancy differences by income means that more affluent US adults can expect to claim those benefits over a longer lifespan.

What would be today’s analog to the Metropolitan Health Law of 1866? Addressing the root causes of health inequity requires interrupting the vicious cycle of poverty leading to illness leading to poverty—what Jacob Bor, ScD, and Sandro Galea, MD, of Boston University School of Health, have termed a “21st century health-poverty trap.” Although there are many root causes to address, perhaps the place to begin is the health of children. For instance, economic policy like the Earned Income Tax Credit has been associated with decreases in low birth weight.

Congress’ recent reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Program offers a glimmer of hope for such bipartisan paths toward health equity nationally. Focusing on resources to support children—such as nurse home visits to pregnant women, prekindergarten programs, and adolescent mental health care— can directly improve health while influencing intergenerational economic mobility. The city of Philadelphia offers a concrete example of how to do this: a tax on sugary drinks was used to fund prekindergarten, social services in neighborhood schools, and parks and libraries. In this way, health might lead to economic opportunity, leading to better health.

Corresponding Author: Dave A. Chokshi, MD, MSc ( [email protected] ).

Published Online: February 21, 2018, at https://newsatjama.jama.com/category/the-jama-forum/ .

Disclaimer: Each entry in The JAMA Forum expresses the opinions of the author but does not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of JAMA, the editorial staff, or the American Medical Association.

Additional Information: Information about The JAMA Forum, including disclosures of potential conflicts of interest, is available at https://newsatjama.jama.com/about/ .

Note: Source references are available through embedded hyperlinks in the article text online.

See More About

Chokshi DA. Income, Poverty, and Health Inequality. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1312–1313. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.2521

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2023

Social inequality, social networks, and health: a scoping review of research on health inequalities from a social network perspective

- Sylvia Keim-Klärner 1 ,

- Philip Adebahr 2 ,

- Stefan Brandt 3 ,

- Markus Gamper 4 ,

- Andreas Klärner 1 ,

- André Knabe 5 ,

- Annett Kupfer 6 ,

- Britta Müller 7 ,

- Olaf Reis 8 ,

- Nico Vonneilich 9 ,

- Maxi A. Ganser 10 ,

- Charlotte de Bruyn 11 &

- Holger von der Lippe 10

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 22 , Article number: 74 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5872 Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This review summarises the present state of research on health inequalities using a social network perspective, and it explores the available studies examining the interrelations of social inequality, social networks, and health.

Using the strategy of a scoping review, as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Int J Sci Res Methodol 8:19–32, 2005), our team performed two searches across eight scientific, bibliographic databases including papers published until October 2021. Studies meeting pre-defined eligibility criteria were selected. The data were charted in a table, and then collated, summarised, and reported in this paper.

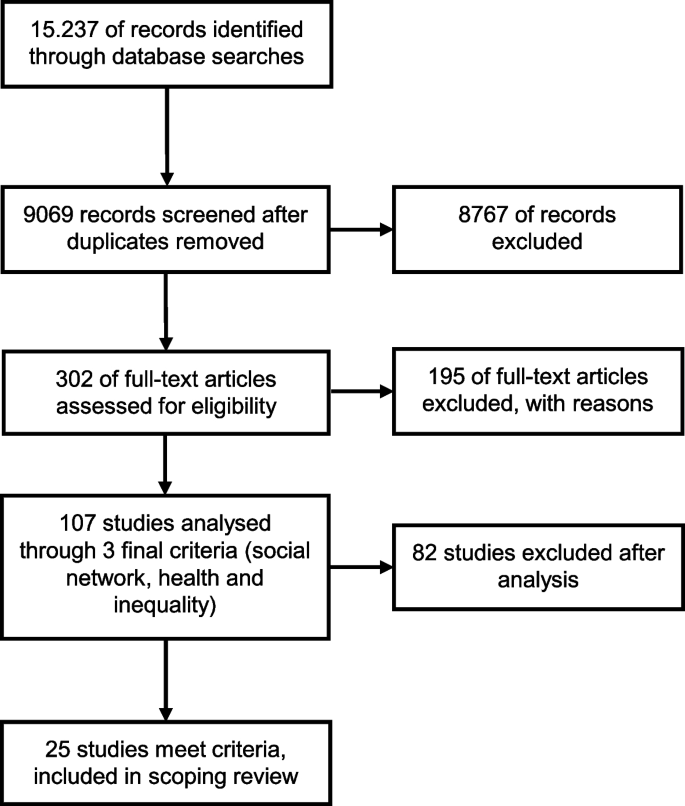

Our search provided a total of 15,237 initial hits. After deduplication ( n = 6,168 studies) and the removal of hits that did not meet our baseline criteria ( n = 8,767 studies), the remaining 302 full text articles were examined. This resulted in 25 articles being included in the present review, many of which focused on moderating or mediating network effects. Such effects were found in the majority of these studies, but not in all. Social networks were found to buffer the harsher effects of poverty on health, while specific network characteristics were shown to intensify or attenuate the health effects of social inequalities.

Conclusions

Our review showed that the variables used for measuring health and social networks differed considerably across the selected studies. Thus, our attempt to establish a consensus of opinion across the included studies was not successful. Nevertheless, the usefulness of social network analysis in researching health inequalities and the employment of health-promoting interventions focusing on social relations was generally acknowledged in the studies. We close by suggesting ways to advance the research methodology, and argue for a greater orientation on theoretical models. We also call for the increased use of structural measures; the inclusion of measures on negative ties and interactions; and the use of more complex study designs, such as mixed-methods and longitudinal studies.

Introduction

This scoping review departs from two meta-analytically substantiated insights into the sociological and psychological determinants of people’s health and health behaviour. First, there is broad evidence that social inequality engenders health inequality : the fewer economic and educational resources individuals possess, the less healthy they typically are, and the fewer – or less effective – health behaviours they exhibit [ 34 , 50 ].

Second, the literature also indicates that networks of personal relationships are important for individuals’ health and health behaviour [ 3 , 44 ]. Analyses of social networks take the structural and compositional features of people’s networks into account. These networks impact people’s health and health behaviour, with the effects ranging from helpful to harmful. For instance, networks that provide individuals with a high degree of social integration typically foster their well-being and promote social learning from their network members [ 44 ]. While these network relationships might lead people to adopt healthy behaviours, they might also push or entice people to engage in unhealthy risk behaviours. Thus, recent studies have examined all three aspects and their interrelationships,that is, they have addressed both social inequality and social networks in the context of research on health differences and inequalities.

In recent years, a large and growing number of empirical studies have examined the interrelationships between social networks and health. Although these findings are promising, research gaps have been pointed out [ 35 , 38 , 41 ]. What has so far been missing in this strand of research is a systematic exploration of how the social network perspective contributes to our understanding of the correlation between social and health inequalities.

From a theoretical point of view, the social network perspective has been identified as having the potential to improve our understanding of health inequalities [ 23 ]. This perspective may be particularly valuable when it focuses on the structures and the mechanisms that influence health outcomes, while also analysing how individual differences are multiplied by social networks, and how social inequalities are reproduced.

Therefore, this paper is guided by two leading questions:

To what extent have existing studies examined social inequality, social networks, and health inequality using a single empirical approach?

What have the findings of these studies revealed about the effects of the structural and the compositional characteristics of social networks on the association between social inequalities and health?

The topic: social networks, health, and social inequalities

Today, the term “social network” is widely used, often in reference to online networks. However, our focus is on the research perspective of social network analysis that defines social networks broadly as “webs of social relationships that surround an individual and the characteristics of those ties” ([ 3 ], p. 145). Such relationships and their interconnections are not volatile,instead, they are arranged in “lasting structures” that are constantly produced and reproduced by interactions ([ 6 ], p. 6). It is this “overall configuration or pattern of relationships” ([ 44 ], p. 6) that is of interest in network research. This configuration may, for example, be captured by:

homogeneity and homophily measures of one’s network members (indices of, respectively, the similarity of one’s network partners and their resemblance to oneself);

measures of the density or redundancy of one’s network (indices that show to what extent a network is or is not loosely knit); or

the presence and the number of bonding ties (the core network of close contacts) or bridging ties (which provide access to resources and information not available within the core network).

While these measures describe specific structural features, network indices form composite measures of different types of relations. An index that is often applied in this context is the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (SNI), which focuses on the isolation/integration of a person, and collects information on the individual’s marital status, number and frequency of contacts with children, close relatives and close friends, church group membership, and membership in other community organisations. By means of such indices, subjects can be categorised into different network types, which are often characterised as having high to low levels of social integration [ 4 ].

An assumption that underlies many network approaches is that social networks “have emergent properties not explained by the constituent parts and not present in the parts” ([ 41 ], p. 407). Thus, network research combines an interest in the specific contacts individuals have in different areas of life (e.g., relatives, friends, colleagues,plus their characteristics) with a focus on their interactions and the functional aspects of these relationships (e.g., social support). Moreover, network research is interested in the larger structure that emerges based on these single ties. Drawing on this perspective, network research goes beyond other measures and concepts of social contacts and interpersonal influences by collecting information not only on the characteristics of the individuals in the network, but also on their relationships and their interconnections.

Social capital research from Bourdieu [ 8 ] to Coleman [ 13 ] or Putnam [ 36 ] has often referred to social networks in defining social capital. However, social capital studies have used structural network measures and network theory to varying degrees, from “building a network theory of social capital” [ 27 ], to focusing exclusively on the aggregate level, by, for example, measuring involvement in organisations and associations (yes/no) and general norms of trust [ 36 ]. These aggregate measures were often based on network theoretical thinking, with the aim of measuring network variables efficiently. For example, involvement in organisations can be used as an indicator of bridging ties without the need to collect complex network data.

Given the inconsistent and often metaphorical use of the term “social networks”, we have provided a definition of social networks that guides us in this review in Table 1 . It specifies that social networks are characterised by relationship characteristics (focusing on different types of relations), by information on the function of relationships (e.g., support), and by structural information on the patterns the relationships form (e.g., density).

In health research, network studies examine the direct impacts of networks on people’s behaviour, as well as the diffusion of ideas, diseases, and behaviours within these structures [ 3 , 44 ].

Unlike in health research, social network studies are not very common in inequality research [ 16 ], even though their concepts have much to offer in investigations of inequality [ 28 ]. Network characteristics such as homophily (“birds of a feather flock together”) or transitivity (“my friend’s friend is also my friend”) can lead to segregated networks of individuals who have either high or low resources, and can therefore not just reproduce social affiliations, but also foster social inequality and inhibit social mobility. People’s social status can affect their opportunities for engaging in beneficial social contacts. For example, an individual with higher social status has access to places (e.g., clubs, business meetings, societal events) where other people in higher social positions meet, and the person can use this access to social resources to advance his/her own career. In contrast, the homogenous network of an individual with lower social status cannot provide him/her with access to such resources [ 7 ]. These dynamics can be directly connected to an individual’s health and health behaviour, as people with higher social status are known to adopt healthier behaviours, and to form relationships with similar individuals, which may also have a positive impact on their health. This pattern can lead to the widening of health disparities [ 33 ]. However, the interrelations of social networks and social inequality are complex. Social networks can also help to reduce social inequality, by, for example, buffering individuals from the detrimental effects of financial deprivation [ 18 ]. The mechanisms involved in how social networks impact individual health or buffer or foster health inequalities are complex and manifold [ 24 ]. It is therefore far beyond the scope of this paper to go into all these possible mechanisms in more detail. In what follows, we focus on moderator and mediator effects of social networks on health inequalities.

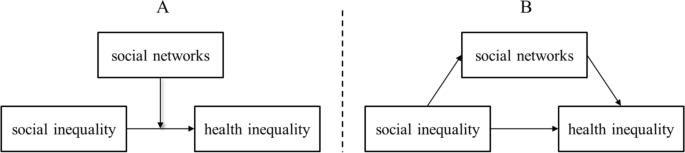

Figure 1 illustrates the most commonly identified types of interconnections between social networks and social and health inequalities. Part A of the figure displays a so-called moderator model. In this model, social networks do not have direct correlations with social or with health inequalities, but they can influence the correlations between these inequalities, by, for instance, having a buffer effect, as was mentioned above. Part B of the figure shows a so-called mediation model. Here, the baseline correlation between social and health inequalities is – fully or partially – altered (“mediated”) by the characteristics of a person’s social networks. In this model, the empirical question of whether the baseline correlation is attenuated (“statistical mediation”) or increased (“statistical suppression”) when social networks are included as a mediating variable remains open.

Schematic representation of moderator ( A ) and mediator ( B ) effects of social networks on health inequality. Source: own display

In the present scoping review, we examine to what extent existing studies have analysed the interconnections of social inequality, social networks, and health inequality using a single empirical approach. We also intend to summarise what the findings of these existing studies have revealed about the effects of the structural and the compositional characteristics of social networks on the association between social inequalities and health.

Methods: reviewing studies using a social network perspective on health inequalities

The literature reviewing process was conducted by the members of a research network on social networks and health inequalities “Soziale Netzwerke und gesundheitliche Ungleichheiten (SoNegU)” funded by the German Research Foundation. The 25 members of this group discussed, scrutinised, and critically assessed the methodological approach and the proceedings of the review on several occasions, a total of 18 members were involved in the article screening. Although we did not strictly follow the PRESS strategy [ 30 ], we employed a third party review of our search strategy by two renowned experts in the field. Given the broad nature of our research questions and the heterogeneity of the studies in the field, we used the method of a scoping review. This method is especially applicable in contexts in which concepts are blurry or heterogeneously understood (as is the case for social networks, social support, social capital), and in which there are a variety of definitions, operationalisation approaches, and research designs that are difficult to compare systematically [ 1 ].

This scoping review strategy follows the method created and outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [ 1 ]. Their methodological framework describes five steps that must be taken to adequately perform a scoping review: 1. Identifying the research question; 2. Identifying relevant studies; 3. Selecting studies; 4. Charting the data; and 5. Collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

Identifying relevant studies: data sources and search terms

The initial literature search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles in English or German language, using the following international and German medical and social science data bases: Pubmed; PsycINFO and MEDLINE via Ovid; Solis (until 2017), SA (Sociological Abstracts, from 2017), SSA (Social Services Abstracts), ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts), and Scopus. The restriction to peer-reviewed articles was made for qualitative and time-efficiency reasons. Because the term "social networks" was often used metaphorically, we had to screen a large number of articles. A restriction to peer-reviewed articles ensured both a high-quality standard and a manageable number of hits. The search was conducted until October 2021. Articles were deemed eligible for inclusion only if they contained at least one search term from each of the following three topics: health, social inequality, and social network analysis. Table 2 displays the search terms that were applied to titles , abstracts, keyword, or MeSH terms of empirical studies . Additional information on how we translated these search terms into MeSH terms is provided in Appendix 1 .

Selecting studies: article screening and eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were consensually determined by the research group. Various preparatory steps (including a pilot trial) were taken to homogenise the evaluation of the literature in the research group (a two-stage pretest, discussion sessions for dissent, etc.). Through this process, a final eligibility list was generated.

Due to the large number of resulting findings, we needed to limit the scope of research to specific contexts. Given our interest in population health, studies focusing on health service use, on specific health issues (e.g., AIDS), or on specific groups (such as homeless individuals, or men who have sex with men) were excluded, as these works may require a separate review. A clear regional focus on OECD countries was also included in the criteria. Table 3 displays all of the study exclusion criteria.

While we began the initial selection process by reviewing titles and abstracts, we then proceeded to review full texts (see Fig. 2 ). We recorded the selected texts, using a spreadsheet, indicating included or excluded texts as well as the reasons for exclusion. After reviewing full texts, it became obvious that some articles used the term “social network” in a rather metaphorical way, and often as a synonym for one-item measurements of social relations or support. We decided to exclude the studies that did not report on more advanced relational, functional, or structural indicators (see the aforementioned social network perspective). Additionally, the empirical connections the studies made between social inequality and social networks were evaluated. Papers that did not relate social inequalities to social networks, but instead treated them as independent controls, were excluded. Figure 2 displays the full sequence of the selection process.

Flowchart of paper selection process (adapted from [ 1 ]). Source: own display

Data charting and final extraction

A resulting and refined 17-column spreadsheet indicated the relevant variables for extraction. This spreadsheet was pilot-tested with 20 papers, discussed in the working group and then provided to all involved in data charting along with examples and an explanatory text. The selected studies were evaluated with regard to characteristics such as research questions, study designs, methods and variables used, and central findings. Appendix 2 illustrates this procedure using the final study selection of this review.

Results: characteristics and main findings of the eligible studies

General characteristics of the final body of studies.

The resulting 25 studies were conducted between 1999 and 2021. Of those, more than half were performed after 2010. Thus, a steady increase in the publication of relevant articles can be observed over the years, with only four of the studies being published before 2005. Of the selected studies, 15 were conducted in Europe, five were conducted in the US, two were conducted in Canada, two were conducted in Australia, and one was conducted in New Zealand.

Given our selection criteria, all 25 studies stem from academic journals, typically from health sector journals such as “Social Science and Medicine” (e.g., [ 9 *, 45 *]) and “Health & Place” (e.g., [ 2 *, 15 *, 46 *]). None of the selected articles had been published in a journal on social network research. Although network journals publish various articles on health issues, these articles did not deal with social inequalities.

Methodological characteristics of the final body of studies

Study design and methodology.

Of the 25 included studies, 24 used quantitative data and performed one or more types of regression analyses. The studies were predominantly cross-sectional, and only seven papers used longitudinal data sets. One study used a mixed-methods design [ 2 *] that began by collecting quantitative data through a postal questionnaire, followed by face-to-face interviews with participants from the questionnaire part. Cattell [ 9 *] was the only purely qualitative study included in this review. Adopting a Grounded Theory approach, this study focused on in-depth face-to-face interviews in two impoverished London neighbourhoods, and developed a typology of social networks in relation to social and health inequalities.

Types of health measurements

The numbers and the types of variables collected in order to quantitatively depict health differentials varied between the studies (cf. also Appendix 2 ). A measure for self-rated, self-reported, subjective, or perceived health was most commonly used, appearing in 11 studies. Nine studies combined three or more health measures; e.g., on physical functioning, mental health, well-being, or vitality. Other studies focused on single measures of general interest, such as BMI (two studies) or resting heart rate (one study). Measures of health behaviour, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, or physical activity, were used as dependent variables in five studies.

Types of social inequality measurements

The included studies showed less variation in their approaches to measuring vertical social inequality. Most common were measures of education and income. Among the other measures used were wealth, perceived income adequacy, employment, occupation, social class, and economic living standard.

Types of social network measurements

The studies included in this review utilised a wide array of variables measuring social networks, including relational, functional, and structural measures (see Appendix 2 ). The relationship characteristics they collected were diverse, and most commonly referred to partnerships, family and friends, and contact frequency. In contrast, one functional characteristic, social support, was used in 15 of the studies. However, these studies varied considerably in the types of support they measured (e.g., emotional, instrumental), and in whether they assumed that the support was needed, perceived, received, or provided. Structural network measures were used in 15 studies, with the variable of network size being the most frequently used (11 studies). In contrast, the use of other structural network measures was rare, and those that were included were diverse. Network density was measured in three studies, and the homogeneity of networks was also measured in three studies. One study focused on homogeneity in terms of ethnicity and gender [ 20 *], while another study focused on homogeneity of belonging to a small number of membership groups [ 9 *], and a third study measured homogeneity of income, age, race, education, being employed, living in the local area, and being family members [ 26 *]. Verhaeghe and colleagues [ 46 *] studied the occupational composition of social networks. Homophily was measured in one study using the I-E Index, which indicated the similarity of alters with ego regarding smoking, age, and education [ 31 *]. The structural constructs of bridging or bonding social relations were applied in three studies. In addition to network measures, 13 studies also used aggregate social capital measures such as trust, neighbourhood cohesion, or community activities.

Most studies covered two of the three named network characteristics: i.e., either relational and functional measures or relational and structural measures. Nine studies were more complex and used variables on multiple types of relationships, network functions, and structural information. For example, Nemeth and colleagues [ 31 *] collected information on the persons the respondent spends the most time with and the persons whom the respondent asks for advice, including information on the characteristics of these persons (e.g., age, smoking status). They also used measures of perceived support (by partner, family, and friends), network size, and density. Four studies reduced complexity by using the Social Network Index (SNI) by Berkman and Syme [ 4 ] and the Social Integration Index (SII), a modified version of the SNI [ 5 ]. These indices captured different types of relations, and they were enriched with additional support or loneliness measures [ 25 *, 29 *, 47 *, 48 *, 49 *].

Main findings of included studies on the interconnections between social inequality, social networks, and health inequality

The interconnections between the crucial three constructs of interest were predominantly analysed using statistical moderator analyses (11 studies) and mediator analyses (nine studies), but multivariate regressions were also applied (six studies). Footnote 1

Social networks as moderators of health inequalities (moderator analysis “type 1”)

Regarding the moderating effect of social networks on the correlation of social inequalities and health inequalities (here termed “type 1”; see Fig. 1 A in the introductory section), the results of four out of five studies showed the relevance of different kinds of social network measures. Richards [ 37 *] and Gele and Harsløff [ 20 *] described moderator effects. Both focused on strong and weak network ties: on close ties, activities in organisations, and having a doctor as a friend [ 20 *], and on friends, support, activities in organisations, and their frequency [ 37 *]. Gele and Harsløff [ 20 *] showed that in their sample, social networks were significant brokers of social resources. For example, they found that being linked to higher educated network partners was beneficial for the respondents’ health, particularly for those with low education. Richards [ 37 *] observed that a high level of social integration acted as a buffer for the negative correlation of well-being and financial strains. Specifically, they found that financial problems impacted a person’s happiness less severely when the person had strong and supportive informal ties as well as extensive weak ties. In the studies by Baum et al. [ 2 *] and Craveiro [ 15 *], neither the relational, structural, nor functional network characteristics under study (e.g., contact frequency, support, network size) were shown to be relevant,but aggregate measures, such as perceived neighbourhood cohesion and safety, social participation, and general network satisfaction, were found to have a moderating effect on health inequalities. However, Craveiro [ 15 *] observed these effects in central and southern Europe only. By contrast, Chappell and Funk [ 10 *] found no similar moderator effects for network size, group membership, community activities, service use, or trust. Emotional support was only used as a control variable in this study.

SES as moderators of network impact on health (moderator analysis “type 2”)

In contrast to the model displayed in Fig. 1 A, and somewhat surprisingly, six studies of the review sample also examined whether social inequality moderated the relationship between social networks and health (here termed “type 2” moderation). Four of these six studies found such moderating effects.

Schöllgen and colleagues [ 40 *] reported that SES had a moderator effect on the relationship between social resources and health. Specifically, they found that network support was more beneficial for the subjective health of individuals with lower than with higher income levels. In a similar vein, Vonneilich et al. [ 47 *] reported that the health risks associated with the lack of emotional and instrumental support were higher for subjects with lower than with higher SES. Focusing and bonding social capital, Kim et al. [ 22 *] showed that the association between social capital and health was moderated by income, with higher bonding social capital being linked with better health for low-income households only. However, the measure of network density, in combination with the health measure BMI, was found to be associated with higher health risks for persons with lower levels of education [ 12 *]. The authors explained this finding by noting that lower educated individuals tend to have less resourceful/supportive and more homophilic social networks. Unfortunately, measures of network homophily or support were not included in this study.

While Unger and colleagues [ 43 *] and Weyers and colleagues [ 49 *] did not find any “type 2” moderator effects in their data, they do no reject the relevance of social networks. The former authors assumed that it could be a mediator effect, and the latter authors stated that having a lower socio-economic position strengthens the influence of social networks on adverse health behaviour.

Social networks as mediators of health inequalities

Regarding the mediating effect of social networks on the correlation of social inequalities with health inequalities (see Fig. 1 B), seven out of nine studies reported such findings. This mediating effect was found in cross-sectional studies as well as in longitudinal studies. The study by Li [ 26 *] found that people of a higher social class were more likely to mobilise their social resources and networks for their own well-being than people of a lower social class. The authors noted, however, that these partial mediation effects of network size and diversity on health and well-being were numerically small compared to the effects of social class. In addition, Verhaeghe et al. [ 46 *] found a prevalent class effect as well as a mediator effect of social networks, with lower levels of social support contributing to a reduction in self-rated health. In a longitudinal study, Klein and colleagues [ 25 *] found that social networks mediated up to 35% of the social inequality effect on self-rated health. They showed that low SES was associated with lower levels of social integration and poorer social support, which in turn led to adverse effects on health. In their longitudinal study, Vonneilich et al. and colleagues [ 48 *] also found a considerable mediating effect, stating that “social relationships substantially contribute to the explanation of SES differences in subjective health” ([ 48 *]: 1/11).

In her qualitative study, Cattell [ 9 *] described how being financially restricted or living in a poor area impeded social participation, which in turn led to a higher risk of social exclusion (smaller networks, less support) and poor health. She also showed that structural social network features (such as density and reciprocity) and functional characteristics (such as support) reduced the harsher effects of poverty on health.

While the mediation studies discussed so far dealt with some indicator of perceived or self-rated health, [ 29 *] demonstrated that social isolation mediated the relationship between SES and resting heart rate by increasing the latter when subjects felt socially isolated and had smaller networks. Looking at different welfare regimes, Craveiro [ 14 *] found that social networks mediated the effects of SES on health, but also that the mediating variables varied across different welfare regimes. However, social support and network satisfaction were found to be consistent mediators in all regions under study.

Two studies did not find any mediating effects. Chappell and Funk [ 10 *] analysed the effects of network size, emotional support, group membership, and community activities on the perceived mental and physical health of individuals with different levels of education and income, while Sabbah and colleagues [ 39 *] researched the mediating effects of support and network size on dental health. However, while the latter authors did not reject the idea that social networks could play a role in inequality in dental health in general, they critically evaluated their applied support measures. Among other measures, they used the subjects’ “need for emotional support”, instead of the more commonly used receipt of support.

Social networks in multivariate models of health inequalities

Another strand of studies refrained from formulating explicit moderator or mediator models. Instead, these six studies investigated social and health inequalities together with social networks in multivariate models without statistical interaction terms. All of these studies showed the relevance of social networks for health inequalities. Stephens and colleagues [ 42 *] found that having a lower income was associated with having less social support, having a more restricted social network, and being less socially integrated, which in turn had detrimental health effects. Moreover, they found these social factors led to a higher risk of loneliness, which was strongly related to several adverse health effects. Similarly, Chavez et al. [ 11 *] demonstrated that people who reported having trust and feelings of reciprocity in their social context had better self-reported health. Although Veenstra [ 45 *] found that income and education were the strongest predictors for health, this author also showed that being socially integrated at work contributed to better self-reported health.

Two of these studies focused on health behaviours. Nemeth and colleagues [ 31 *] showed that when strong neighbourhood cohesion was combined with the belief in the general acceptability of smoking in a deprived neighbourhood, and when social networks contained many smokers, it was more difficult for smokers to quit, as doing so would jeopardise their social acceptance. Kamphuis and colleagues [ 21 *] showed that social networks played an important role in differences in sports participation, as people with lower SES, smaller networks, and less network cohesion had lower levels of sports participation.

The longitudinal study by Novak and colleagues [ 32 *] introduced network characteristics from past study waves as “parental control in school” and “not being popular in school”. They showed that people who had low education as well as these social network characteristics during their school years were more likely to be obese in adulthood.

Discussion and conclusion

Health inequalities have been investigated and discussed in research for many decades, and form an established research topic. Social network analysis, by contrast, is a novel research approach, but one that is gaining in popularity. Thus, the present scoping review was guided by two main questions: to what extent have existing studies examined social inequality, social networks, and health inequality using a joint empirical approach; and what have the findings of these studies revealed about the effects of the structural and the compositional characteristics of social networks on the association between social and health inequalities?

Despite the large number of initial hits in the literature research (9,064), after we reviewed the papers’ contents in more detail, we found a comparatively small number of publications (25) that fitted the aim of this review. A typical phenomenon that occurred during the selection process was that at first glance, many articles seemed suitable based on the term “social networks” in their abstract. At second glance, however, we found that the authors often used this term rather metaphorically for some unspecified kind of social relations or support. In these articles, which we excluded from this review, the authors neither made connections to the theoretical concepts or to methods of social network analysis; nor explored different types of relationships, analysed network functions, or measured structural network characteristics. Thus, despite the recent prominence of the term “social network”, there are only a few studies on health inequalities that can clearly be identified as social network analyses.