Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2018

Quantitative account of social interactions in a mental health care ecosystem: cooperation, trust and collective action

- Anna Cigarini 1 , 2 ,

- Julián Vicens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0643-0469 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Jordi Duch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2639-6333 3 , 4 ,

- Angel Sánchez 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 &

- Josep Perelló ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8533-6539 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 8 , Article number: 3794 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

9676 Accesses

12 Citations

51 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Applied mathematics

- Human behaviour

- Psychology and behaviour

- Public health

An Author Correction to this article was published on 26 September 2018

This article has been updated

Mental disorders have an enormous impact in our society, both in personal terms and in the economic costs associated with their treatment. In order to scale up services and bring down costs, administrations are starting to promote social interactions as key to care provision. We analyze quantitatively the importance of communities for effective mental health care, considering all community members involved. By means of citizen science practices, we have designed a suite of games that allow to probe into different behavioral traits of the role groups of the ecosystem. The evidence reinforces the idea of community social capital, with caregivers and professionals playing a leading role. Yet, the cost of collective action is mainly supported by individuals with a mental condition - which unveils their vulnerability. The results are in general agreement with previous findings but, since we broaden the perspective of previous studies, we are also able to find marked differences in the social behavior of certain groups of mental disorders. We finally point to the conditions under which cooperation among members of the ecosystem is better sustained, suggesting how virtuous cycles of inclusion and participation can be promoted in a ‘care in the community’ framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reformulating computational social science with citizen social science: the case of a community-based mental health care research

Investigation of turning points in the effectiveness of Covid-19 social distancing

An agent-based model of social care provision during the early stages of Covid-19

Introduction.

Approximately one fifth of the world population will suffer some mental disorder (MD) at some point in their lives, such as anxiety or depression 1 . The direct economic costs of MD, including care and indirect effects, is estimated to reach $6 trillion in 2030, which is more than cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases combined 2 . As part of a global effort to scale up services and bring down costs, reliance is increasingly made upon informal social networks 3 . A holistic approach to mental health promotion and care provision is then necessary, and emphasis is placed on the idea of individuals-in-community: individuals with MD are defined not just alone but in relationship to others 4 . Such a paradigm shift implies superseding the traditional physician-patient dyad to include caregivers, relatives, social workers, and the community as a whole, recognizing their crucial role in the recovery process.

A key aspect in the definition and aetiology of MD has to do with social behavior 5 : behavioral symptoms, or consequences at the behavioral level, characterize most MD. For instance, autism, social phobia, or personality disorders are determined by the presence of impairments in social interaction. Other disorders result in significant difficulties in the social domain, such as depression or psychotic disorders. Further, conditions that are intrinsically behavioral (as for eating disorders or substance abuse) seem to be exacerbated by the influence of social peers. A large body of research has therefore looked at the neural basis of social decision-making among individuals with MD to identify objective biomarkers that may prove useful for its diagnosis, therapy evaluation, and understanding 6 , 7 , 8 . However, such a methodology does not well fit into the individuals-in-community paradigm. We argue that an agent-based approach which draws upon experimental game theory might prove insightful and ecologically valid for the study of behavior in a given social environment.

Within the mental health literature, the use of game theory as a way to understand the multi-faceted dimensions of behavior has received already quite some attention 9 , 10 . Most research addressed the issue of behavioral differences between individuals with MD and healthy populations 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 . These works, that point to cognitive and affective processing impairments 6 , 16 , 17 , further support the idea that MDs are associated with significant and pervasive difficulties in social cognition and altered decision-making at various levels. Yet, despite these studies are of very much interest, they are primarly concerned with dyadic interactions among people with specific MDs. That is, they lack insights into the complexity of individual behaviors of MD within a specific social context.

Here we adopt a novel community perspective. Our objective is twofold: First, we aim to develop a thorough taxonomy of the behavioral traits of role groups within the collective. We thus account for both the heterogeneity of actors, and for multiple types of social interactions. We strongly believe that to predict and understand behavior is necessary to consider the relationship context in which individuals are embedded. Therefore diversity of roles, motivations or capabilities, must be taken into account. Also, real life social interactions occur in different forms; sometimes people must work together, some others they have to coordinate or anti-coordinate their behaviors, yet in other situations they find themselves in more or less disadvantaged positions. It is therefore of crucial importance to encompass a comprehensive range of strategic situations if we are to appreciate behavior. That is, traits such as trust, altruism, or reciprocity, along with the person’s own expectations, all play a role in the process of decision making in social contexts. This calls for an experimental approach in which participants face several strategic settings. Our second objective is to provide quantitative accounts of social capital within the mental health community, bringing the notion of social capital into the forefront of mental health care. Far from being universally defined, its core contention is that social networks are a valuable asset, providing a basis for social cohesion and cooperation towards a common goal 18 (which is, in our case, mental care provision). It thus encompasses those norms and forces that shape social interactions, serving as the glue that holds society together 19 .

For these purposes, we have designed an experimental setup that probes into the complexity of the interdependencies at play within the mental health ecosystem. Accordingly, our experiments take place in a socialized, lab-in-the-field setting 20 , in order to be as close as possible to the dynamic and unique nature of real-life social interactions. The design of our socialized setup is based on a participatory process and citizen science practices 20 which counted on the collaboration of all stakeholders of the mental health ecosystem. By combining all these ingredients, we have developed a framework that, as will be shown below, allows to capture some difficult-to-observe aspects of behavior and social capital within mental health ecosystems as a way to understand how communities contribute to care and resocialization.

A full description of the games we implemented can be found in the Methods section below, but for clarity we briefly describe here the games we used. We had participants play two dyadic games, namely the Trust game, in which they had to lend money to another player who then obtains a return, and has the option to send some money back to the lender; players played in both roles. They also played the well known Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which they had to choose to cooperate or to try to benefit from the other’s cooperation. Finally, they played a collective risk dilemma, in which the whole group had to reach a common goal to avert a catastrophe that most likely would wipe out their money. Participants belonging to the mental health ecosystem played with each other in group of six players. However, they could by no means guess with whom they were actually playing.

We begin the presentation of our results from the dyadic games of our suite of strategic interactions. Aggregate behavioral measures point to systematic deviations from self-interested predictions which are in line with previous literature on experimental game play 21 . In the Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD), the average cooperation rate across all individuals is c = 0.61 ± 0.03 (standard error of the mean), which is notoriously well above the Nash equilibrium prediction of c = 0. Participants behavior in the PD is also significantly associated with their estimates about the likely cooperation of the partner ( \({\chi }^{2}=32.48\) , p = 1.2 · 10 8 ), with 44% of all participants expecting the partner to cooperate, and thus cooperating themselves. This points to the crucial role of positive expectations on cooperative behavior 22 . Further, participants trust and reciprocate positive amounts in the Trust Game (5.79 ± 0.15 monetary units (MU) and 41.3 ± 1.37% of the amount available to return, respectively), again departing largely from Nash equilibrium conjectures of 0 MU transferred. The results also suggest that in considering the mental health community in its whole, thus accounting for the diversity of actors and roles, the global picture does not substantially differ from society at large.

Sectorial and dyadic behavior

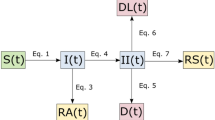

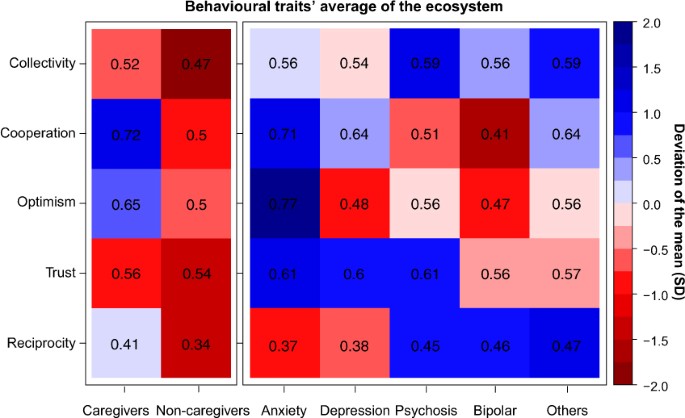

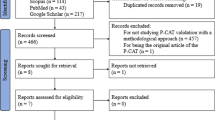

As we stated above, our main interest is to delve into the behavior of the different actors who make up the mental health ecosystem Fig. 1 summarizes the results for the five groups of individuals concerned. The heatmap yields several insights that are worth commenting upon.

Heatmap of behavioural traits’ average and deviation of the mean across games. Collectivity refers to the ratio of contribution in the Collective-Risk Social Dilemma. Cooperation and Optimism refers to the ratio of cooperation and expected cooperation, respectively, in Prisoner’s Dilemma. Trust and Reciprocity refers to the ratio of capital trusted and reciprocated in Trust Game. The left part shows the ratio of individuals without mental conditions: caregivers (professionals and relatives with caregiving tasks) and non-caregivers (relatives without caregiving tasks, friends and others). The right part shows the actions of individuals with mental conditions. Therefore, the number in each cell indicates the ratio of social preferences per subjects in each social dilemma and the color scale shows the deviation of the mean measured in SD units.

In one-shot dyadic interactions some marked differences in the frequency of cooperative behaviors (PD) arise within the collective formed by affected with MD, caregivers, non-caregivers (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, \(H=6.04,df=2,p=0.0488\) ). Further pairwise comparisons (see Supplementary Table S1 ) show that participants with anxiety and caregivers are more likely to opt for the cooperative strategy compared to participants with bipolar disorder, psychosis or other members of the collective. Participants with anxiety are also the ones with the most positive expectations about the partner’s behavior compared to all but caregivers (see Supplementary Table S2 ). Also, relatives, friends and other members with no MD defect more than caregivers (Mann-Whitney U test, \(U=1352,p=0.02839\) ), being relatives remarkably less cooperative than the rest of the collective c = 0.33 ± 0.16. This suggests that cooperation among members of the mental health ecosystem is contextually based, depending on the role that actors play in the recovery process. It also varies across diagnostics, revealing a marked cooperativeness and optimism of individuals with anxiety disorders.

On the other hand, in sequential dyadic interactions (TG) all participants trust more than half of their endowment, being the distribution of initial transfers similar across groups. No variation is indeed found in trust levels between participants with MD, caregivers and non caregivers (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, \(H=2.75,df=2,p=0.25\) ). Yet, at the time of reciprocating the partner’s behavior, participants with anxiety and depression return the least (37.5 ± 3.3%). The difference is significant if compared to return transfers of participants with psychosis or other diagnostics (see Supplementary Table S4 ).

Group interaction

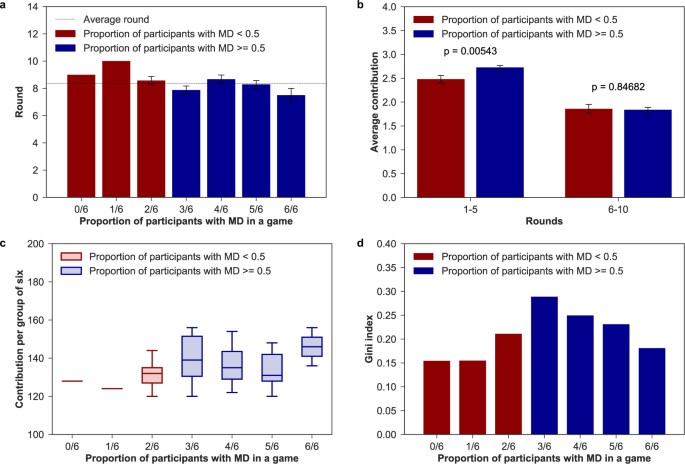

Our experimental setup has proven extremely informative in its most novel section, namely the analysis of group interactions framed within the Collective Risk Dilemma (CRD), with no prior result within the mental health literature. In global terms, the average amount contributed to the public good (22.6 MUs) is much more than the fair contribution of 20 MUs, where by fair we understand sharing equally the total amount needed for the threshold (120 MUs) among all six participants. Here it is important to keep in mind that participants were told that all money contributed would go to reforestation projects, so it is not irrational to keep contributing beyond the threshold as many of our subjects did. The key result in the CRD is that large, significant differences (t-test, \(t=2.85,df=242,p=0.0047\) ) are found between participants with and without mental disorders. The former contribute with 22.95 ± 0.63 MUs compared to 20.34 ± 0.68 MUs from the latter, and therefore it appears that when repeated interaction and sustained teamwork (CRD) are required, people with MD contribute much more to the common goal (See Supplementary Section 1.6.2).

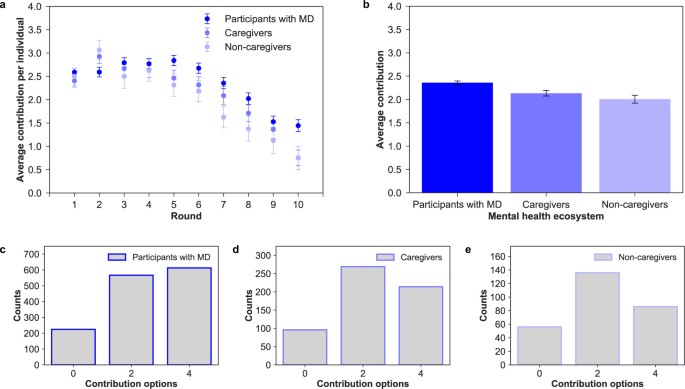

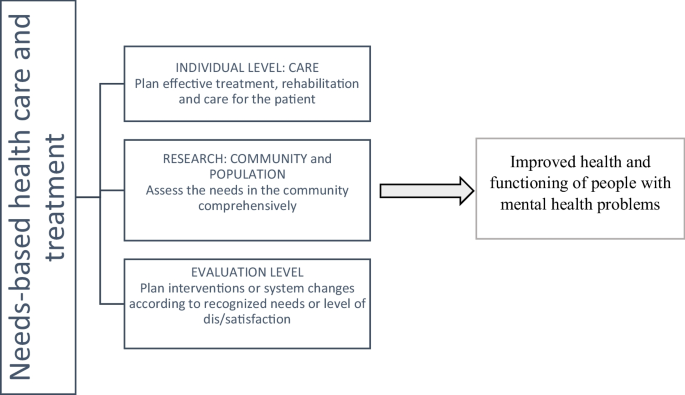

Contribution dynamics vary according to group composition in terms of number of participants with mental disorder conditions and other actors involved in the recovery process. All groups successfully reach the target collecting on average 135.64 ± 1.75 MUs (see Supplementary Section 1.6.1). Similarly to other public good experiments, contributions decrease over time 23 . While in the first round participants contribute around 56.3% of the allowed contribution per round (2.2 ± 0.07 MUs, where the social optimum is 2 MU), contributions drop when the endgame effect sets in. A Spearman’s rank-order correlation of contributions over rounds corroborates this negative time trend ( \(\rho =-0.757,p < 0.05\) ). Both patients and actors involved in the recovery process reduce their contributions by the end of the game. However, in almost all rounds, participants with a mental condition contribute more than caregivers and non caregivers, for whom motivations to contribute decline steadily (see Fig. 2 ).

(a) Individual contribution over rounds. Evolution of contributions (mean and standard error of the mean) during the game between participants with mental disorder conditions, caregivers and non-caregivers. We can see that all groups behave similarly and in an identical way to a previous experiment run outside the mental health ecosystem 40 . (b) Average individual contribution per round. Average contribution and standard error of the mean in the mental health ecosystem. There are significant differences between participant with MD and the rest of actors, caregivers (t-test, \(t=2.107,df=155,p < 0.0294\) ) and non-caregivers (t-test, \(t=2.499,df=48,p=0.01588\) ). Distribution of choices by participants with MD ( c ), caregivers (d) and non-caregivers ( e ). The most of participants with MD (43.6%) selected the maximum contribution (4), while the caregivers (46.5%) and non-caregivers (48.9%) mostly selected the fair contribution (2).

In terms of the group composition, groups where individuals with MD conditions constitute half or the majority of the group (n = 36) do much better in sustaining cooperation compared to groups where firsthand affected are the minority (n = 9). It is here worth to mention that participants may see who the rest of the members are but ignore who is exactly making the choice in the game (see Methods for further details). As Fig. 3b shows, while average individual contributions are similar in the last periods (rounds 6–10 t-test, t = 0.19, p = 0.85), groups with half or more individuals with MD contribute significantly more at the beginning of the game (rounds 1–5 t-test, t = 2.79, p = 0.0054). Hence, the presence of three or more individuals with a mental condition in the group has a positive and stabilizing effect on average individual contributions. Likewise, in games with a low proportion of participants affected with MD the group achieved the goal, on average, later than in games with more than 50% of participants affected with MD (see Fig. 3a ).

(a) Average round of achievement. Round (mean and standard error of the mean) in which the group of six achieved the target. (b) Aggregated contributions per group composition. Contributions (mean and standard error of the mean) in the first and last five-rounds per number of individuals with MD in a group. There are significant differences (t-test p < 0.01) in contributions in the first part of the game. (c ) Contributions per group of six. Total group contributions by number of individuals with mental conditions in the group. (d ) Gini index of final payoff within groups. Level of inequality in final payoff based on the number of individuals with MD in each group.

If we then break down the analysis by group type, we find that group members contribute and benefit differently from cooperation (see Fig. 3c ). Indeed, final payoffs within groups are far from being equally distributed (see Fig. 3d ), with the highest inequality found in the group where the number of patients equals the number of actors involved in the recovery process (Gini coefficient = 0.289). We thus see clearly that the cost of collective action is mainly supported by individuals with a mental disorder. Given that they contribute the most within all groups, lower investments are needed for other members of the collective to reach the common target. Yet, in 4/6 and 5/6 groups caregivers reduce average individual contributions while non-caregivers pay more than their fair share. In 1/6 and 2/6 groups, on the other hand, caregivers are the ones who compensate the unfair contributions of other members. These last groups are the ones that ensure the lowest inequality in final payoffs. Therefore, while our results are unambiguous about the larger readiness for collective action among people with MD, we cannot claim nothing about the rest of the collective.

Let us now turn to the discussion of the above results and their implications (see Table 1 for a summary of the key findings). As a first general remark, through our lab-in-the field experiment we found that an ecosystem approach to mental health care brings with it a quite complex scenario with several interesting insights. To begin with, participants with anxiety symptoms display a markedly different behavior compared to other diagnostics: they are more likely to opt for the cooperative strategy compared to individuals with bipolar disorder or depression, and return significantly less than participants with psychosis or other disorders. Since the current study is the first to investigate social decision-making within a heterogeneous population of individuals diagnosed with MD, a comparison with previous research is only possible referring to studies focusing on specific clinical and quite homogeneous populations. Several experiments have demonstrated deficits in cooperative behavior among individuals with anxiety or depression when playing iterated versions of the PD 11 , 17 , 24 , 25 , but results about altruism (Ultimatum Game) and trust are inconsistent between studies 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 , 17 , 26 . Individuals with major depressive disorders (which include anxiety and depressive symptoms) have also been found to systematically differ when their emotional responses to fairness are compared 6 , 17 , showing higher levels of negative feelings when faced with unfair treatments. One of the hypothesis advanced to explain the systematic behavioral differences of individuals with anxiety relates to a potentiated sensitivity to negative stimuli as well as a tendency to treat neutral or ambiguous stimuli as negative or as less positive 6 , 12 , 17 , 27 . This hypothesis might find support in our results as for the low returns in the Trust Game, despite displaying relatively high trust in the partner’s behavior and very high expectations. Indeed, participants with depressive or anxiety symptoms in our experiment significantly over-punish trustee transfers, but the low returns are independent of the amount received. This seems to imply that participants with mood disorders respond negatively to their partner behavior, as if they interpret their partner’s choice in a negative sense. Alternatively, fairness considerations may be playing a role: low returns of participants with mood disorders might therefore be due to different fairness perceptions 6 , 12 , 17 , which result in a bias towards negative reactions rather than positive rewarding.

Deficits in economic game play have also been documented for individuals with bipolar disorder. Studies report low and decreasing trust levels over sequential interactions, skeptical beliefs about the partner’s behavior and a tendency to break cooperative interactions 28 , 29 . Again, this is partly supported by our results. Negative expectations of participants with bipolar disorder indeed agree with a low frequency of cooperative choices, little amounts of money sent to trustees, and low contributions to collective action. In line with King-Casas et al . results 29 , while individuals with depression trust in the cooperativeness of other people, those with bipolar personality disorders do not. Cognitive dysfunctions (insula response) might possibly reflect an atypical social norm in this group 29 . Consequently, defection by partners might not violate the social expectations of individuals with BPD. In contrast, in our experiment, participants with bipolar disorder return the most within the group of individuals with a mental disorder. That is, they report a strong willingness to positively respond to a norm of trust as to signal their partner trustworthiness. Therefore, conditioned on the previous action of the partner, it seems that individuals with BPD are willing to show cooperative behavior. Considering now individuals with high levels of psychopathy, they have been found to make less fair offers, accept less fair offers, and show very high levels of defection 15 , 16 , 30 . Major explanations for such behavior point to deficits in emotion regulations (amygdala dysfunctions), which would lead to lack of anxiety, empathy, and guilt, coupled with exaggerated levels of anger and frustration 30 and to the absence of prepotent biases toward minimizing the distress of others 16 . In this case, our experiments do not confirm those previous results: Indeed, participants with psychosis are the ones who trust, contribute the most to the public good, and are willing to take costly actions to reciprocate their partner’s behavior. It could be possible that, as psychopathic disorders are in fact a large group of different ones, behavioral differences among subgroups may lead to this discrepancy. In connection with these results, it is interesting to note that recent results on a large population of patients with paranoia suggest that distrust is not the best explanation for reduced cooperation and alternative explanations incorporating self-interest might be more relevant 31 , 32 . This calls for further research into this particular family of MD to clarify whether or not the behavioral characterization applies to all or to a subclass of them.

However, pointing to deficits in social cognition can only account for a partial explanation of individual behavior, and does not contribute to community care narratives. The fact that nothing in this direction has been reported before also reinforces the need to adopt a more holistic view on the interdependencies at play within the mental health collective. Indeed, if statistically relevant differences in cooperative behavior are found across diagnostics, they also depend on the role that actors play in the recovery process. That is, caregivers display exceedingly large degrees of cooperativeness and optimism in one-shot interactions. Caregivers can be thus considered the strong ties of the mental health ecosystem, of particular value when one seeks emotional support. With the de-institutionalization of health systems, caregivers have indeed become key players in care provision. Taking into account their behavior and expectations is therefore of particular interest to extend the support tailored to their needs. These actions should improve the effectiveness of their role by guiding them 33 . Yet, relatives who do not strictly contribute to caregiving practices turn out to be the weak links. It is thus likely that interventions designed to increase their participation in the community might help improve the recovery process.

Also, members of the mental health ecosystem do not equally contribute and benefit from collective action. Rather, systematic behavioral differences arise as the number of social interactions increase, i.e., when teamwork is required for the collective to benefit as a whole. This suggests that considering repeated games may prove extremely insightful for the purpose of the research. Indeed, our experiments show that individuals with MD are the ones who contribute the most to the public good: they make larger efforts towards reaching the collective goal, thus playing a leading role for the functioning of the ecosystem. As a consequence, groups with half or more participants with MD do better in sustaining cooperation in the first rounds, which implies that a community care setting might prove successful for capability building. Yet, large proportions of individuals with MD in a group result in higher inequalities in final gains, which reach the maximum when the number of individuals with MD equals the number of caregivers or relatives. This means that community care perspectives might also take account of group composition to deal with potential inequalities arising from differential capabilities. In summary, we have explored the behavior of all individuals and role groups who make up the mental health ecosystem through an extensive suite of games that simulate strategic social situations. Overall, the results point to the availability of large social capital in the mental health community that can make a difference in the welfare and recovery process of firsthand affected, and suggest that the community-centered approach to mental care may turn out to be very beneficial. Indeed, the behavior of individuals with MD can be better explained by examining not only their cognitive abilities, but also the web of relationships in which they are embedded. Yet, that web of relationships presents opportunities and imposes constraints.

Though we depicted some behavioral differences in dyadic interactions, most importantly we found that individuals with MD show a remarkably larger disposition towards sustaining cooperation within groups. The larger readiness of individuals with MD to contribute to the collective action problem can thus be seen as a way to claim their place in the community. By having participants unaware of their partner’s identity, we could indeed measure participants decisions based solely on the value they placed on the group’s welfare, independently of its composition or other factors. Yet, the fact that participants with MD contribute the most implies for other members of the group lower investments to reach the common target. This, on the other hand, unveils the vulnerability of individuals with a diagnosis of MD. Repeated or periodic and more situated experiments with digital platforms 34 , in the future, can surely provide further valuable insights into the effect of participants prior knowledge of and relation with the partner on their behavior. We are indeed sure that our experimental setup can prove helpful in complementing the diagnostic process of physicians and health professionals and even to evaluate care service providers. On the other hand, other possible application of this approach arises in the realm of behavior change interventions 35 , that should focus on the aspects that are more specific of every disorder.

In conclusion, the results reinforce the idea of community social capital as a key approach to the recovery process based on an ecosystem paradigm (see also the recent results in ref. 36 about the role and impact of family and community social capital on MD in children and adolescents). Also, if on the one hand the fact that the results of our dyadic games are in general agreement with previous studies validates our procedure; on the other hand it supports the validity and contributions of neuroeconomics and experimental approaches to the study of MD. Finally, given that our work has been carried out in a fully socialized context, this approach can be applied to any similar’ ‘care in the community’ initiative. The adoption of our setup could lead to the identification of core groups that can boost and sustain cooperation within a given community. It can also help in discriminating among different communities in order to identify best practices and optimize resource allocation 37 .

All participants were fully informed about the purpose, methods and intended uses of the research. No participant could approach any experimental station without having signed a written informed consent. The use of pseudonyms ensured the anonymity of participants’ identity, in agreement with the Spanish Law for Personal Data Protection. No association was ever made between the participants’ real names and the results. The whole procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitat de Barcelona. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental design

As indicated in the main text, the dialogue with the main stakeholders of the mental health ecosystem was at the centre of the project. Around 20 representatives including members of the Catalonia Federation of Mental Health (Federació Salut Mental Catalunya), firsthand affected, relatives, caregivers, and other professionals related to both the health and social sector, informed and validated the whole research through focus groups and further discussions, leading to the largest experiment of this kind ever carried out. Citizen science principles guided the whole experimental design process in order to raise concerns grounded in the daily life of mental health professionals and service users, and to increase public awareness. The experimental dilemmas being proposed served both to advance in knowledge on the social dynamics at play within ‘care in the community’ settings and as a self-reflection experience for all participants. The experimental design process developed in four main phases: (i) identification of the behavioral traits perceived as of fundamental importance within the community, (ii) operationalization of those same behavioral traits thorugh game theoretical paradigms and literature reviews, (iii) definition of the socio-demographic information relevant for the analysis, and (iv) a beta testing of the digital interface (including contents, time duration, and language used). The locations where the experiments took place were accorded with the Catalonia Federation of Mental Health in an attempt to explore the functioning of some communities of interest for inclusive and effective policy making. The Federation provided a fundamental support throughout the whole experiments’ implementation, serving as a crucial intermediaire between the scientists and different mental health collectives. It also provided valuable insights to better interpret the data obtained.

Participants and procedure

To our knowledge, experimental work on this issue has been conducted only recently and on specific collectives of orders of magnitude smaller. A total of 270 individuals participated in the experiments, that were run over 45 sessions between October 2016 and March 2017. The experiments were carried out in Girona (n = 60), Lleida (n = 120), Sabadell (n = 48) and Valls (n = 42). Participants were either diagnosed with a mental condition (n = 169) or members of the broader mental health ecosystem (n = 101), including professionals of the health and social sector (n = 52), formal and informal caregivers (n = 17), relatives (n = 9), friends (n = 4) and other members of the collective (n = 19). Individuals with a mental condition had to self-assess their diagnosis selecting one from a spectrum of options agreed upon with representatives of the mental health ecosystem during the co-design phases of the experiment. Those participants who had received more than one diagnosis had to select the one they considered to be the most relevant. Overall, they had received a diagnosis of psychosis (n = 63), depression (n = 33), anxiety (n = 31), bipolar disorder (n = 17) or other unspecified diagnosis (n = 25). They ranged in age from 21 to 77 years old (these are weighted values since for ethical and privacy reasons participants were only asked to choose among different age ranges) with 47.2 years on average. Further, 55.6% were men and 44.4% were women. Yet, actors involved in the recovery process were predominantly women (76.2%), and up to 21.8% of them was over 60 years old (see Supplementary Section 1.1). Participants were told that they would play against each others a set of games meant to explore human decision-making processes. They played in random groups of six players through a web interface specifically developed for the research. They were informed that they had to make a decision under different conditions and against different opponents in every round. Every game represented an interactive situation requiring the participants to make a decision, the result of which depended also on the opponent’s behavior. To incentivize the participation, they would earn a voucher worth their final score (the experimental settings and instructions, can be found in the Supplementary Section 1.2 and 1.3 respectively). First, participants participated in a Collective Risk Dilemma 23 against five opponents. Briefly, the game is a public goods game with threshold: If the participants’ total contribution after 10 rounds is lower than a given threshold, they loose all the money they kept with a probability of 90%. Otherwise, they are told that the money collected in the common fund are spent in reforesting land plots in Catalonia, where the experimental sessions took place, and each participants earns the money left in the personal account. After completing the task, participants played one round of the Trust Game 38 in both roles: as trustors and as trustees. They played against different partners in each role. Finally, they played one round of a Prisoner Dilemma 39 with (unincentivized) belief elicitation about their counterpart’s behavior prior to playing. Before starting the games, participants had to complete a brief survey covering some key dimensions of their sociodemographic background. The assignment of players’ partners in the dyadic games was completely random and every action was made with a different partner. The average (standard error of the mean) time for completing the three experiments (CRD, PD and TG and tutorials) is around 12 minutes, 705.86 ± 17.93 s. At the end of each session, participants received a gift card worth their earnings. The average individual earning is 46.84 ± 0.77 MUs equivalent to a 4.04 ± 0.077 EUR voucher. The behavioral patterns that emerged do not reveal significant variation across the different experiments, which may suggest that our results are robust to generalizations (see Supplementary Section 1.7).

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed at two levels: first, we tested for behavioral differences between the whole group of individuals with mental condition compared to members of the mental health ecosystem; we then checked for systematic behavioral variation across diagnostics and role played in the recovery process. In one shot, two-person dyadic interactions we performed Mann-Whitney-U tests for independent groups to compare the distributions of cooperative choices (PD), and initial and back transfers (TG), between individuals with and without a mental condition. We then checked for marginal differences within groups using Kruskal-Wallis tests, and post-hoc comparisons were run with Mann-Whitney-U tests adjusting for p-values with the Holm-Bonferroni method. Welch’s two-tailed t-tests were performed to check for differences in average contributions (CRD) between participants with and without a MD, controlling for unequal variances and sample sizes. Finally, ANOVA and further Tukey HSD post-hoc comparisons served to check for differences in average contributions over round across diagnostics and members of the mental health community.

Accession codes

Data is available in an structured way at Zenodo public repository with DOI 10.5281/zenodo.1175627.

Change history

26 september 2018.

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

Steel, Z. et al . The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43 , 476–493 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Insel, T. R., Collins, P. Y. & Hyman, S. E. Darkness invisible: The hidden global costs of mental illness. Foreign Affairs 94 (2015).

White, R. G., Jain, S., Orr, D. M. R. & Read, U. M. The Palgrave handbook of sociocultural perspectives on global mental health. The Palgrave handbook of sociocultural perspectives on global mental health. (2017).

Chapter Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2001: mental health, new understanding, new hope. World Health Report 1–169 (2001).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition TR. (2000).

Gradin, V. B. et al . Abnormal brain responses to social fairness in depression: an fMRI study using the Ultimatum Game. Psychol. Med. 45 , 1241–51 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Shao, R., Zhang, H. & Lee, T. M. C. The neural basis of social risky decision making in females with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychologia 67 , 100–10 (2015).

Guroglu, B., van den Bos, W., Rombouts, S. A. R. B. & Crone, E. A. Unfair? It depends: Neural correlates of fairness in social context. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 5 , 414–423 (2010).

Wang, Y., Yang, L. –Q., Li, S. & Zhou, Y. Game Theory Paradigm: A New Tool for Investigating Social Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 6 , 128 (2015).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

King–Casas, B. & Chiu, P. H. Understanding interpersonal function in psychiatric illness through multiplayer economic games. Biol. Psychiatry 72 , 119–125 (2012).

Pulcu, E. et al . Social–economical decision making in current and remitted major depression. Psychol. Med. 45 , 1–13 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al . Impaired social decision making in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 14 , 18 (2014).

Csukly, G., Polgár, P., Tombor, L., Réthelyi, J. & Kéri, S. Are patients with schizophrenia rational maximizers? Evidence from an ultimatum game study. Psychiatry Res. 187 , 11–17 (2011).

Agay, N., Kron, S., Carmel, Z., Mendlovic, S. & Levkovitz, Y. Ultimatum bargaining behavior of people affected by schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 157 , 39–46 (2008).

Mokros, A. et al . Diminished cooperativeness of psychopaths in a prisoner’s dilemma game yields higher rewards. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 117 , 406–413 (2008).

Rilling, J. K. et al . Neural Correlates of Social Cooperation and Non-Cooperation as a Function of Psychopathy. Biol. Psychiatry 61 , 1260–1271 (2007).

Scheele, D., Mihov, Y., Schwederski, O., Maier, W. & Hurlemann, R. A negative emotional and economic judgment bias in major depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 263 , 675–683 (2013).

Putnam, R. D. Bowling Aalone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. J. Democr. 6 , 1–18 (2000).

Google Scholar

Ostrom, E. In Handbook of Social Capital: The troika of sociology, political science and economics, pp. 17–35 (2009).

Sagarra, O., Gutiérrez-Roig, M., Bonhoure, I. & Perelló, J. Citizen science practices for computational social science research: The conceptualization of pop-up experiments. Front. Phys. 3 , 93 (2016).

Camerer, C.F., Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction (Princeton University Press, 2003).

Brañas-Garza, P., Rodríguez-Lara, I. & Sánchez, A. Humans expect generosity. Sci. Rep. 7 , 42446 (2017).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Milinski, M., Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H.-J., Reed, F. A. & Marotzke, J. The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Nat’l. Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 2291–2294 (2008).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Surbey, M. K. Adaptive significance of low levels of self-deception and cooperation in depression. Evol. Hum. Behav. 32 , 29–40 (2011).

Clark, C. B., Thorne, C. B., Hardy, S. & Cropsey, K. L. Cooperation and depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 150 , 1184–1187 (2013).

Destoop, M., Schrijvers, D., De Grave, C., Sabbe, B. & De Bruijn, E. R. A. Better to give than to take? Interactive social decision–making in severe major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 137 , 98–105 (2012).

Harlé, K. M., Allen, J. J. B., Sanfey, A. G., Harlé, K. M. & Sanfey, A. G. The impact of depression on social economic decision making. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 119 , 440–446 (2010).

Unoka, Z., Seres, I., Aspán, N., Bódi, N. & Kéri, S. Trust game reveals restricted interpersonal transactions in patients with borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 23 , 399–409 (2009).

King-Casas, B. et al . The rupture and repair of cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Science 321 , 806–810 (2008).

Koenigs, M., Kruepke, M. & Newman, J. P. Economic decision-making in psychopathy: A comparison with ventromedial prefrontal lesion patients. Neuropsychologia 48 , 2198–2204 (2010).

Raihani, N. J. & Bell, V. Paranoia and the social representation of others: a large-scale game theory approach. Scientific Reports 7 , 4544, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04805-3 (2017).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Raihani, N. J. & Bell, V. Conflict and cooperation in paranoia: a large-scale behavioural experiment. Psychological Medicine 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003075 (2017).

Collins, L. G. & Swartz, K. Caregiver care. American family physician 83 , 1309–1317 (2011).

PubMed Google Scholar

Aledwood, T. et al . Data collection for mental health studies through digital platforms: requirements and design of a prototype. JMIR research protocols 6 (6), 1–11 (2017).

Blaga, O. M., Vasilescu, L. & Chereches, R. M. Use and effectiveness of behavioural economics in interventions for lifestyle risk factors of non-communicable diseases: a systematic review with policy implications. Perspectives in Public Health 20 (10), 1–11 (2017).

McPherson, K. E. et al . The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: an integrative systematic review. BMC psychology 2 , 7, https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7283-2-7 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Almedom, A. M. Social capital and mental health: An interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Social Science and Medicine 61 , 943–964 (2005).

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J. & McCabe, K. Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econ. Behav. 10 , 122–142 (1995).

Rapoport, A. & Chammah, A. M. Prisoner’s Dilemma (University of Michigan Press, 1965).

Vicens, J. et al . Resource heterogeneity leads to unjust effort distribution in climate change mitigation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.02857 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the community of patients, caregivers and families working within the Federació de Salut Mental Catalunya (Catalonia Mental Health Federation) for the enthusiasm and for their invaluable help in the design and realization of the experiments. We are also especially thankful to I Bonhoure for the necessary logistics to make the experiments possible, to F Español for contributing in the first steps in the experimental design, to M Poll for always giving us the institutional support from inside the Federation, to both E Ferrer and F Muñoz for building the bridge between us and the mental health ecosystem and to X Trabado for encouraging us to run this research. This work was partially supported by Federació de Salut Mental Catalunya; by MINEICO (Spain), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) through grants FIS2013-47532-C3-1-P (JD), FIS2016-78904-C3-1-P (JD), FIS2013-47532-C3-2-P (JP), FIS2016-78904-C3-2-P (JP, AC); by Generalitat de Catalunya (Spain) through Complexity Lab Barcelona (contract no. 2014 SGR 608, JP) and through Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca (contract no. 2013 DI 49, JD, JV); and by the EU through FET Open Project IBSEN (contract no. 662725, AS) and FET-Proactive Project DOLFINS (contract no. 640772, AS).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Departament de Física de la Matèria Condensada, Universitat de Barcelona, 08028, Barcelona, Spain

Anna Cigarini, Julián Vicens & Josep Perelló

Universitat de Barcelona Institute of Complex Systems UBICS, 08028, Barcelona, Spain

Departament d’Enginyeria Informàtica i Matemàtiques, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, 43007, Tarragona, Spain

Julián Vicens & Jordi Duch

Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems (NICO), Northwestern University, 60208, Evanston, IL, USA

Grupo Interdisciplinar de Sistemas Complejos (GISC), Unidad de Matemática, Modelización y Ciencia Computacional, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 28911, Leganés, Spain

Angel Sánchez

Unidad Mixta Interdisciplinar de Comportamiento y Complejidad Social (UMICCS) UC3M-UV-UZ, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 28911, Leganés, Spain

Institute UC3M-BS of Financial Big Data, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 28903, Getafe, Spain

Instituto de Biocomputación y Física de Sistemas Complejos (BIFI), Universidad de Zaragoza, 50009, Zaragoza, Spain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.D., A.S., and J.P. conceived the original idea for the experiment; J.V. and J.D. prepared the software for the final experimental setup; A.C. and J.V. analyzed the data; and all authors carried out the experiments, discussed the analysis results, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Josep Perelló .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cigarini, A., Vicens, J., Duch, J. et al. Quantitative account of social interactions in a mental health care ecosystem: cooperation, trust and collective action. Sci Rep 8 , 3794 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21900-1

Download citation

Received : 15 November 2017

Accepted : 01 February 2018

Published : 28 February 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21900-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental Health

- Community Social Capital

- Group Roles

- Dyadic Games

- Average Individual Contribution

This article is cited by

Gender-based pairings influence cooperative expectations and behaviours.

- Anna Cigarini

- Julián Vicens

- Josep Perelló

Scientific Reports (2020)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: AI and Robotics newsletter — what matters in AI and robotics research, free to your inbox weekly.

- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 10 October 2019

An integrative review on methodological considerations in mental health research – design, sampling, data collection procedure and quality assurance

- Eric Badu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0593-3550 1 ,

- Anthony Paul O’Brien 2 &

- Rebecca Mitchell 3

Archives of Public Health volume 77 , Article number: 37 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

20 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Several typologies and guidelines are available to address the methodological and practical considerations required in mental health research. However, few studies have actually attempted to systematically identify and synthesise these considerations. This paper provides an integrative review that identifies and synthesises the available research evidence on mental health research methodological considerations.

A search of the published literature was conducted using EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search was limited to papers published in English for the timeframe 2000–2018. Using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, three reviewers independently screened the retrieved papers. A data extraction form was used to extract data from the included papers.

Of 27 papers meeting the inclusion criteria, 13 focused on qualitative research, 8 mixed methods and 6 papers focused on quantitative methodology. A total of 14 papers targeted global mental health research, with 2 papers each describing studies in Germany, Sweden and China. The review identified several methodological considerations relating to study design, methods, data collection, and quality assurance. Methodological issues regarding the study design included assembling team members, familiarisation and sharing information on the topic, and seeking the contribution of team members. Methodological considerations to facilitate data collection involved adequate preparation prior to fieldwork, appropriateness and adequacy of the sampling and data collection approach, selection of consumers, the social or cultural context, practical and organisational skills; and ethical and sensitivity issues.

The evidence confirms that studies on methodological considerations in conducting mental health research largely focus on qualitative studies in a transcultural setting, as well as recommendations derived from multi-site surveys. Mental health research should adequately consider the methodological issues around study design, sampling, data collection procedures and quality assurance in order to maintain the quality of data collection.

Peer Review reports

In the past decades there has been considerable attention on research methods to facilitate studies in various academic fields, such as public health, education, humanities, behavioural and social sciences [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. These research methodologies have generally focused on the two major research pillars known as quantitative or qualitative research. In recent years, researchers conducting mental health research appear to be either employing both qualitative and quantitative research methods separately, or mixed methods approaches to triangulate and validate findings [ 5 , 6 ].

A combination of study designs has been utilised to answer research questions associated with mental health services and consumer outcomes [ 7 , 8 ]. Study designs in the public health and clinical domains, for example, have largely focused on observational studies (non-interventional) and experimental research (interventional) [ 1 , 3 , 9 ]. Observational design in non-interventional research requires the investigator to simply observe, record, classify, count and analyse the data [ 1 , 2 , 10 ]. This design is different from the observational approaches used in social science research, which may involve observing (participant and non- participant) phenomena in the fieldwork [ 1 ]. Furthermore, the observational study has been categorized into five types, namely cross-sectional design, case-control studies, cohort studies, case report and case series studies [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The cross-sectional design is used to measure the occurrence of a condition at a one-time point, sometimes referred to as a prevalence study. This approach of conducting research is relatively quick and easy but does not permit a distinction between cause and effect [ 1 ]. Conversely, the case-control is a design that examines the relationship between an attribute and a disease by comparing those with and without the disease [ 1 , 2 , 12 ]. In addition, the case-control design is usually retrospective and aims to identify predictors of a particular outcome. This type of design is relevant when investigating rare or chronic diseases which may result from long-term exposure to particular risk factors [ 10 ]. Cohort studies measure the relationship between exposure to a factor and the probability of the occurrence of a disease [ 1 , 10 ]. In a case series design, medical records are reviewed for exposure to determinants of disease and outcomes. More importantly, case series and case reports are often used as preliminary research to provide information on key clinical issues [ 12 ].

The interventional study design describes a research approach that applies clinical care to evaluate treatment effects on outcomes [ 13 ]. Several previous studies have explained the various forms of experimental study design used in public health and clinical research [ 14 , 15 ]. In particular, experimental studies have been categorized into randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled trials, and quasi-experimental designs [ 14 ]. The randomized trial is a comparative study where participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups. This research examines a comparison between a group receiving treatment and a control group receiving treatment as usual or receiving a placebo. Herein, the exposure to the intervention is determined by random allocation [ 16 , 17 ].

Recently, research methodologists have given considerable attention to the development of methodologies to conduct research in vulnerable populations. Vulnerable population research, such as with mental health consumers often involves considering the challenges associated with sampling (selecting marginalized participants), collecting data and analysing it, as well as research engagement. Consequently, several empirical studies have been undertaken to document the methodological issues and challenges in research involving marginalized populations. In particular, these studies largely addresses the typologies and practical guidelines for conducting empirical studies in mental health. Despite the increasing evidence, however, only a few studies have yet attempted to systematically identify and synthesise the methodological considerations in conducting mental health research from the perspective of consumers.

A preliminary search using the search engines Medline, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus Index and EMBASE identified only two reviews of mental health based research. Among these two papers, one focused on the various types of mixed methods used in mental health research [ 18 ], whilst the other paper, focused on the role of qualitative studies in mental health research involving mixed methods [ 19 ]. Even though the latter two studies attempted to systematically review mixed methods mental health research, this integrative review is unique, as it collectively synthesises the design, data collection, sampling, and quality assurance issues together, which has not been previously attempted.

This paper provides an integrative review addressing the available evidence on mental health research methodological considerations. The paper also synthesises evidence on the methods, study designs, data collection procedures, analyses and quality assurance measures. Identifying and synthesising evidence on the conduct of mental health research has relevance to clinicians and academic researchers where the evidence provides a guide regarding the methodological issues involved when conducting research in the mental health domain. Additionally, the synthesis can inform clinicians and academia about the gaps in the literature related to methodological considerations.

Methodology

An integrative review was conducted to synthesise the available evidence on mental health research methodological considerations. To guide the review, the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of mental health has been utilised. The WHO defines mental health as: “a state of well-being, in which the individual realises his or her own potentials, ability to cope with the normal stresses of life, functionality and work productivity, as well as the ability to contribute effectively in community life” [ 20 ]. The integrative review enabled the simultaneous inclusion of diverse methodologies (i.e., experimental and non-experimental research) and varied perspectives to fully understand a phenomenon of concern [ 21 , 22 ]. The review also uses diverse data sources to develop a holistic understanding of methodological considerations in mental health research. The methodology employed involves five stages: 1) problem identification (ensuring that the research question and purpose are clearly defined); 2) literature search (incorporating a comprehensive search strategy); 3) data evaluation; 4) data analysis (data reduction, display, comparison and conclusions) and; 5) presentation (synthesising findings in a model or theory and describing the implications for practice, policy and further research) [ 21 ].

Inclusion criteria

The integrative review focused on methodological issues in mental health research. This included core areas such as study design and methods, particularly qualitative, quantitative or both. The review targeted papers that addressed study design, sampling, data collection procedures, quality assurance and the data analysis process. More specifically, the included papers addressed methodological issues on empirical studies in mental health research. The methodological issues in this context are not limited to a particular mental illness. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed articles published in the English Language, from January 2000 to July 2018.

Exclusion criteria

Articles that were excluded were based purely on general health services or clinical effectiveness of a particular intervention with no connection to mental health research. Articles were also excluded when it addresses non-methodological issues. Other general exclusion criteria were book chapters, conference abstracts, papers that present opinion, editorials, commentaries and clinical case reviews.

Search strategy and selection procedure

The search of published articles was conducted from six electronic databases, namely EMBASE, CINAHL (EBSCO), Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO and Medline. We developed a search strategy based on the recommended guidelines by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [ 23 ]. Specifically, a three-step search strategy was utilised to conduct the search for information (see Table 1 ). An initial limited search was conducted in Medline and Embase (see Table 1 ). We analysed the text words contained in the title and abstract and of the index terms from the initial search results [ 23 ]. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was then repeated across all remaining five databases (see Table 1 ). Finally, the reference lists of all eligible studies were manually hand searched [ 23 ].

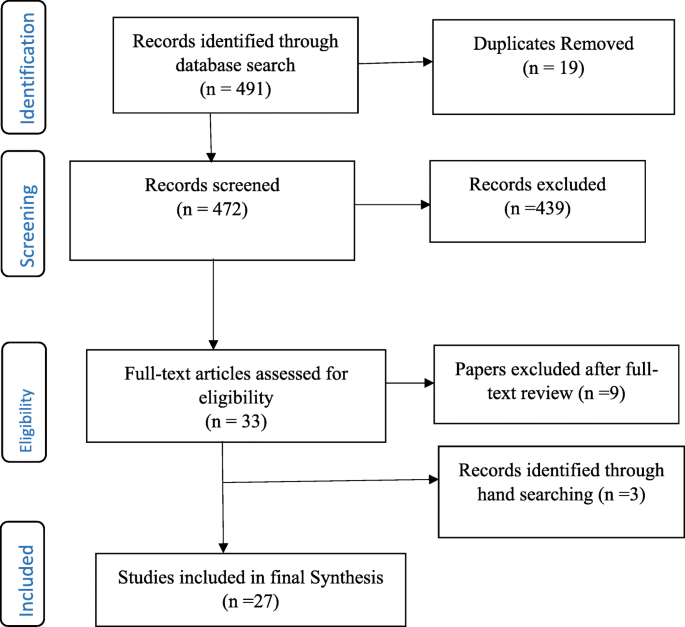

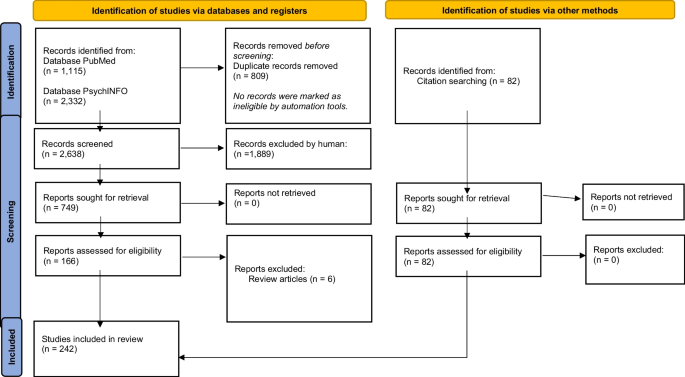

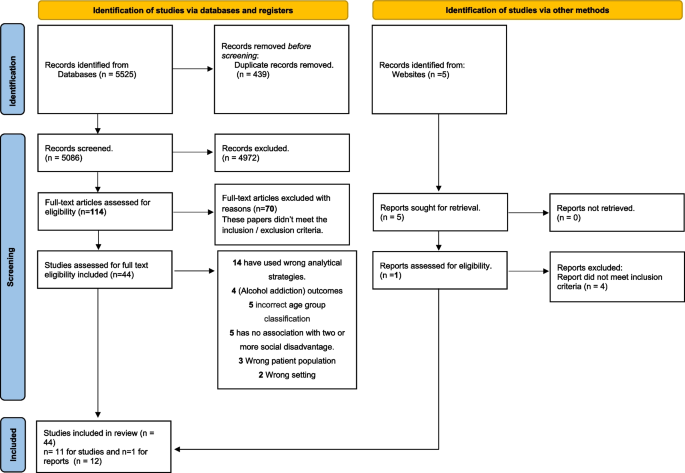

The selection of eligible articles adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 24 ] (see Fig. 1 ). Firstly, three authors independently screened the titles of articles that were retrieved and then approved those meeting the selection criteria. The authors reviewed all the titles and abstracts and agreed on those needing full-text screening. E.B (Eric Badu) conducted the initial screening of titles and abstracts. A.P.O’B (Anthony Paul O’Brien) and R.M (Rebecca Mitchell) conducted the second screening of titles and abstracts of all the identified papers. The authors (E.B, A.P.O’B and R.M) conducted full-text screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Flow Chart of studies included in the review

Data management and extraction

The integrative review used Endnote ×8 to screen and handle duplicate references. A predefined data extraction form was developed to extract data from all included articles (see Additional file 1 ). The data extraction form was developed according to Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [ 23 ] and Cochrane [ 24 ] manuals, as well as the literature associated with concepts and methods in mental health research. The data extraction form was categorised into sub-sections, such as study details (citation, year of publication, author, contact details of lead author, and funder/sponsoring organisation, publication type), objective of the paper, primary subject area of the paper (study design, methods, sampling, data collection, data analysis, quality assurance). The data extraction form also had a section on additional information on methodological consideration, recommendations and other potential references. The authors extracted results of the included papers in numerical and textual format [ 23 ]. EB (Eric Badu) conducted the data extraction, A.P.O’B (Anthony Paul O’Brien) and R.M (Rebecca Mitchell), conducted the second review of the extracted data.

Data synthesis

Content analysis was used to synthesise the extracted data. The content analysis process involved several stages which involved noting patterns and themes, seeing plausibility, clustering, counting, making contrasts and comparisons, discerning common and unusual patterns, subsuming particulars into general, noting relations between variability, finding intervening factors and building a logical chain of evidence [ 21 ] (see Table 2 ).

Study characteristics

The integrative review identified a total of 491 records from all databases, after which 19 duplicates were removed. Out of this, 472 titles and abstracts were assessed for eligibility, after which 439 articles were excluded. Articles not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded. Specifically, papers excluded were those that did not address methodological issues as well as papers addressing methodological consideration in other disciplines. A total of 33 full-text articles were assessed – 9 articles were further excluded, whilst an additional 3 articles were identified from reference lists. Overall, 27 articles were included in the final synthesis (see Fig. 1 ). Of the total included papers, 12 contained qualitative research, 9 were mixed methods (both qualitative and quantitative) and 6 papers focused on quantitative data. Conversely, a total of 14 papers targeted global mental health research and 2 papers each describing studies in Germany, Sweden and China. The papers addressed different methodological issues, such as study design, methods, data collection, and analysis as well as quality assurance (see Table 3 ).

Mixed methods design in mental health research

Mixed methods research is defined as a research process where the elements of qualitative and quantitative research are combined in the design, data collection, and its triangulation and validation [ 48 ]. The integrative review identified four sub-themes that describe mixed methods design in the context of mental health research. The sub-themes include the categories of mixed methods, their function, structure, process and further methodological considerations for mixed methods design. These sub-themes are explained as follows:

Categorizing mixed methods in mental health research

Four studies highlighted the categories of mixed methods design applicable to mental health research [ 18 , 19 , 43 , 48 ]. Generally, there are differences in the categories of mixed methods design, however, three distinct categories predominantly appear to cross cut in all studies. These categories are function, structure and process. Some studies further categorised mixed method design to include rationale, objectives, or purpose. For instance, Schoonenboom and Johnson [ 48 ] categorised mixed methods design into primary and secondary dimensions.

The function of mixed methods in mental health research

Six studies explain the function of conducting mixed methods design in mental health research. Two studies specifically recommended that mixed methods have the ability to provide a more robust understanding of services by expanding and strengthening the conclusions from the study [ 42 , 45 ]. More importantly, the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods have the ability to provide innovative solutions to important and complex problems, especially by addressing diversity and divergence [ 48 ]. The review identified five underlying functions of a mixed method design in mental health research which include achieving convergence, complementarity, expansion, development and sampling [ 18 , 19 , 43 ].

The use of mixed methods to achieve convergence aims to employ both qualitative and quantitative data to answer the same question, either through triangulation (to confirm the conclusions from each of the methods) or transformation (using qualitative techniques to transform quantitative data). Similarly, complementarity in mixed methods integrates both qualitative and quantitative methods to answer questions for the purpose of evaluation or elaboration [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. Two papers recommend that qualitative methods are used to provide the depth of understanding, whilst the quantitative methods provide a breadth of understanding [ 18 , 43 ]. In mental health research, the qualitative data is often used to examine treatment processes, whilst the quantitative methods are used to examine treatment outcomes against quality care key performance targets.

Additionally, three papers indicated that expansion as a function of mixed methods uses one type of method to answer questions raised by the other type of method [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. For instance, qualitative data is used to explain findings from quantitative analysis. Also, some studies highlight that development as a function of mixed methods aims to use one method to answer research questions, and use the findings to inform other methods to answer different research questions. A qualitative method, for example, is used to identify the content of items to be used in a quantitative study. This approach aims to use qualitative methods to create a conceptual framework for generating hypotheses to be tested by using a quantitative method [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. Three papers suggested that using mixed methods for the purpose of sampling utilize one method (eg. quantitative) to identify a sample of participants to conduct research using other methods (eg. qualitative) [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. For instance, quantitative data is sequentially utilized to identify potential participants to participate in a qualitative study and the vice versa.

Structure of mixed methods in mental health research

Five studies categorised the structure of conducting mixed methods in mental health research, into two broader concepts including simultaneous (concurrent) and sequential (see Table 3 ). In both categories, one method is regarded as primary and the other as secondary, although equal weight can be given to both methods [ 18 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 48 ]. Two studies suggested that the sequential design is a process where the data collection and analysis of one component (eg. quantitative) takes place after the data collection and analysis of the other component (eg qualitative). Herein, the data collection and analysis of one component (e.g. qualitative) may depend on the outcomes of the other component (e.g. quantitative) [ 43 , 48 ]. An earlier review suggested that the majority of contemporary studies in mental health research use a sequential design, with qualitative methods, more often preceding quantitative methods [ 18 ].

Alternatively, the concurrent design collects and analyses data of both components (e.g. quantitative and qualitative) simultaneously and independently. Palinkas, Horwitz [ 42 ] recommend that one component is used as secondary to the other component, or that both components are assigned equal priority. Such a mixed methods approach aims to provide a depth of understanding afforded by qualitative methods, with the breadth of understanding offered by the quantitative data to elaborate on the findings of one component or seek convergence through triangulation of the results. Schoonenboom and Johnson [ 48 ] recommended the use of capital letters for one component and lower case letters for another component in the same design to indicate that one component is primary and the other is secondary or supplemental.

Process of mixed methods in mental health research

Five papers highlighted the process for the use of mixed methods in mental health research [ 18 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 48 ]. The papers suggested three distinct processes or strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative data. These include merging or converging the two data sets, connecting the two datasets by having one build upon the other; and embedding one data set within the other [ 19 , 43 ]. The process of connecting occurs when the analysis of one dataset leads to the need for the other data set. For instance, in the situation where quantitative results lead to the subsequent collection and analysis of qualitative data [ 18 , 43 ]. A previous study suggested that most studies in mental health sought to connect the data sets. Similarly, the process of merging the datasets brings together two sets of data during the interpretation, or transforms one type of data into the other type, by combining the data into new variables [ 18 ]. The process of embedding data into mixed method designs in mental health uses one dataset to provide a supportive role to the other dataset [ 43 ].

Consideration for using mixed methods in mental health research

Three studies highlighted several factors that need to be considered when conducting mixed methods design in mental health research [ 18 , 19 , 45 ]. Accordingly, these factors include developing familiarity with the topic under investigation based on experience, willingness to share information on the topic [ 19 ], establishing early collaboration, willingness to negotiate emerging problems, seeking the contribution of team members, and soliciting third-party assistance to resolve any emerging problems [ 45 ]. Additionally, Palinkas, Horwitz [ 18 ] recommended that mixed methods in the context of mental health research are mostly applied in studies that assess needs of services, examine existing services, developing new or adapting existing services, evaluating services in randomised control trials, and examining service implementation.

Qualitative study in mental health research

This theme describes the various qualitative methods used in mental health research. The theme also addresses methodological considerations for using qualitative methods in mental health research. The key emerging issues are discussed below:

Considering qualitative components in conducting mental health research

Six studies recommended the use of qualitative methods in mental health research [ 19 , 26 , 28 , 32 , 36 , 44 ]. Two qualitative research paradigms were identified, including the interpretive and critical approach [ 32 ]. The interpretive methodologies predominantly explore the meaning of human experiences and actions, whilst the critical approach emphasises the social and historical origins and contexts of meaning [ 32 ]. Two studies suggested that the interpretive qualitative methods used in mental health research are ethnography, phenomenology and narrative approaches [ 32 , 36 ].

The ethnographic approach describes the everyday meaning of the phenomena within a societal and cultural context, for instance, the way phenomena or experience is contrasted within a community, or by collective members over time [ 32 ]. Alternatively, the phenomenological approach explores the claims and concerns of a subject with a speculative development of an interpretative account within their cultural and physical environments focusing on the lived experience [ 32 , 36 ].

Moreover, the critical qualitative approaches used in mental health research are predominantly emancipatory (for instance, socio-political traditions) and participatory action-based research. The emancipatory traditions recognise that knowledge is acquired through critical discourse and debate but are not seen as discovered by objective inquiry [ 32 ]. Alternatively, the participatory action based approach uses critical perspectives to engage key stakeholders as participants in the design and conduct of the research [ 32 ].

Some studies highlighted several reasons why qualitative methods are relevant to mental health research. In particular, qualitative methods are significant as they emphasise naturalistic inquiry and have a discovery-oriented approach [ 19 , 26 ]. Two studies suggested that qualitative methods are often relevant in the initial stages of research studies to understand specific issues such as behaviour, or symptoms of consumers of mental services [ 19 ]. Specifically, Palinkas [ 19 ] suggests that qualitative methods help to obtain initial pilot data, or when there is too little previous research or in the absence of a theory, such as provided in exploratory studies, or previously under-researched phenomena.

Three studies stressed that qualitative methods can help to better understand socially sensitive issues, such as exploring the solutions to overcome challenges in mental health clinical policies [ 19 , 28 , 44 ]. Consequently, Razafsha, Behforuzi [ 44 ] recommended that the natural holistic view of qualitative methods can help to understand the more recovery-oriented policy of mental health, rather than simply the treatment of symptoms. Similarly, the subjective experiences of consumers using qualitative approaches have been found useful to inform clinical policy development [ 28 ].

Sampling in mental health research

The theme explains the sampling approaches used in mental health research. The section also describes the methodological considerations when sampling participants for mental health research. The sub-themes emerging are explained in the following sections:

Sampling approaches (quantitative)

Some studies reviewed highlighted the sampling approaches previously used in mental health research [ 25 , 34 , 35 ]. Generally, all quantitative studies tend to use several probability sampling approaches, whilst qualitative studies used non-probability techniques. The quantitative mental health studies conducted at community and population level employ multi-stage sampling techniques usually involving systematic sampling, stratified and random sampling [ 25 , 34 ]. Similarly, quantitative studies that recruit consumers in the hospital setting employ consecutive sampling [ 35 ]. Two studies reviewed highlighted that the identification of consumers of mental health services for research is usually conducted by service providers. For instance, Korver, Quee [ 35 ] research used a consecutive sampling approach by identifying consumers through clinicians working in regional psychosis departments, or academic centres.

Sampling approaches (qualitative)