An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Research Topics

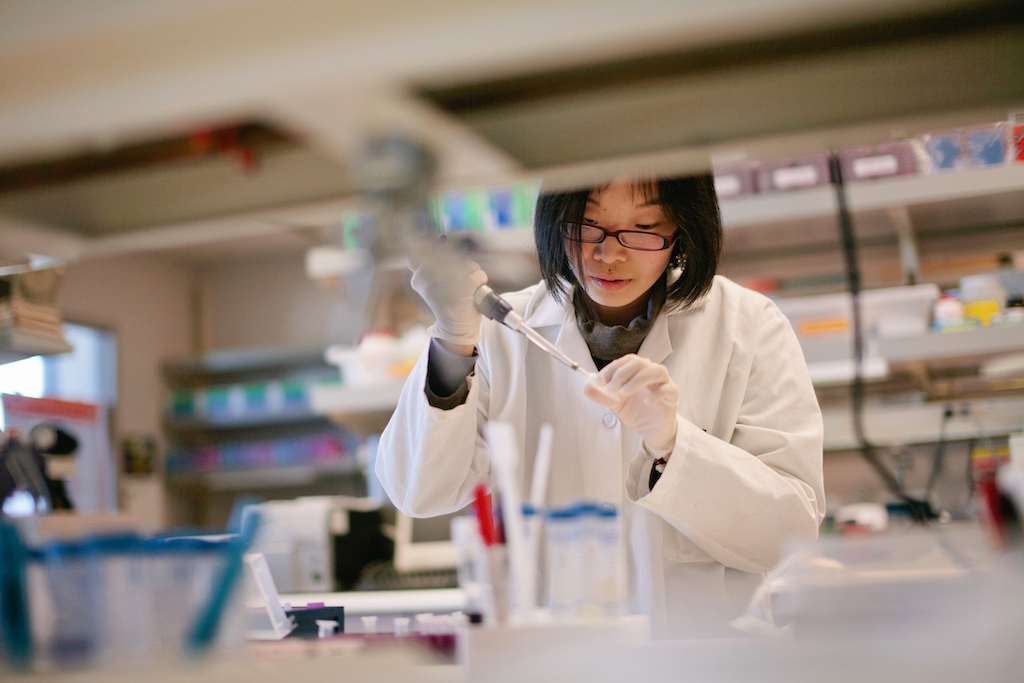

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) is the largest supporter of the world’s research on substance use and addiction. Part of the National Institutes of Health, NIDA conducts and supports biomedical research to advance the science on substance use and addiction and improve individual and public health. Look below for more information on drug use, health, and NIDA’s research efforts.

Information provided by NIDA is not a substitute for professional medical care.

In an emergency? Need treatment?

In an emergency:.

- Are you or someone you know experiencing severe symptoms or in immediate danger? Please seek immediate medical attention by calling 9-1-1 or visiting an Emergency Department . Poison control can be reached at 1-800-222-1222 or www.poison.org .

- Are you or someone you know experiencing a substance use and/or mental health crisis or any other kind of emotional distress? Please call or text 988 or chat www.988lifeline.org to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. 988 connects you with a trained crisis counselor who can help.

FIND TREATMENT:

- For referrals to substance use and mental health treatment programs, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or visit www.FindTreatment.gov to find a qualified healthcare provider in your area.

- For other personal medical advice, please speak to a qualified health professional. Find more health resources on USA.gov .

DISCLAIMER:

The emergency and referral resources listed above are available to individuals located in the United States and are not operated by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). NIDA is a biomedical research organization and does not provide personalized medical advice, treatment, counseling, or legal consultation. Information provided by NIDA is not a substitute for professional medical care or legal consultation.

Research by Substance

Find evidence-based information on specific drugs and substance use disorders.

- Cannabis (Marijuana)

- Commonly Used Drugs Charts

- Emerging Drug Trends

- Methamphetamine

- MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)

- Over-the-Counter Medicines

- Prescription Medicines

- Psilocybin (Magic Mushrooms)

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs as Medicines

- Steroids (Anabolic)

- Synthetic Cannabinoids (K2/Spice)

- Synthetic Cathinones (Bath Salts)

- Tobacco/Nicotine and Vaping

Drug Use and Addiction

Learn how science has deepened our understanding of drug use and its impact on individual and public health.

- Addiction Science

- Comorbidity

- Drug Checking

- Drug Testing

- Drugged Driving

- Drugs and the Brain

- Harm Reduction

- Infographics

- Mental Health

- Monitoring the Future

- National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS)

- Overdose Death Rates

- Overdose Prevention Centers

- Overdose Reversal Medications

- Stigma and Discrimination

- Syringe Services Programs

- Trauma and Stress

- Trends and Statistics

- Words Matter: Preferred Language for Talking About Addiction

People and Places

NIDA research supports people affected by substance use and addiction throughout the lifespan and across communities.

- The Adolescent Brain and Substance Use

- College-Age and Young Adults

- Criminal Justice

- Global Health

- LGBTQI+ People and Substance Use

- Military Life and Substance Use

- National Drug and Alcohol Facts Week Organizers and Participants

- Older Adults

- Parents and Educators

- Pregnancy and Early Childhood

- Sex, Gender, and Drug Use

Related Resources

- Learn more about Overdose Prevention from the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Learn more about substance use treatment, prevention, recovery support, and related services from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration .

- Learn more about the health effects of alcohol and alcohol use disorder from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism .

- Learn more the approval and regulation of prescription medicines from the Food and Drug Administration .

- Learn more about efforts to measure, prevent, and address public health impacts of substance use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention .

- Learn more about controlled substance law and regulation enforcement from the Drug Enforcement Administration .

- Learn more about policies impacting substance use from the Office of National Drug Control Policy .

- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

Drug Abuse, Addiction, Substance Use Disorder

- Research Drug Abuse

Start Learning About Your Topic

Create research questions to focus your topic, find books in the library catalog, find articles in library databases, find web resources, cite your sources, key search words.

Use the words below to search for useful information in books and articles .

- substance use disorder

- substance abuse

- drug addiction

- substance addiction

- chemical dependency

- war on drugs

- names of specific drugs such as methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin

- opioid crisis

Background Reading:

It's important to begin your research learning something about your subject; in fact, you won't be able to create a focused, manageable thesis unless you already know something about your topic.

This step is important so that you will:

- Begin building your core knowledge about your topic

- Be able to put your topic in context

- Create research questions that drive your search for information

- Create a list of search terms that will help you find relevant information

- Know if the information you’re finding is relevant and useful

If you're working from off campus , you'll be prompted to log in just like you do for your MJC email or Canvas courses.

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- Gale eBooks This link opens in a new window Use this database for preliminary reading as you start your research. Try searching these terms: addiction, substance abuse

Other eBooks from the MJC Library collection:

Use some of the questions below to help you narrow this broad topic. See "substance abuse" in our Developing Research Questions guide for an example of research questions on a focused study of drug abuse.

- In what ways is drug abuse a serious problem?

- What drugs are abused?

- Who abuses drugs?

- What causes people to abuse drugs?

- How do drug abusers' actions affect themselves, their families, and their communities?

- What resources and treatment are available to drug abusers?

- What are the laws pertaining to drug use?

- What are the arguments for legalizing drugs?

- What are the arguments against legalizing drugs?

- Is drug abuse best handled on a personal, local, state or federal level?

- Based on what I have learned from my research what do I think about the issue of drug abuse?

Why Use Books:

Use books to read broad overviews and detailed discussions of your topic. You can also use books to find primary sources , which are often published together in collections.

Where Do I Find Books?

You'll use the library catalog to search for books, ebooks, articles, and more.

What if MJC Doesn't Have What I Need?

If you need materials (books, articles, recordings, videos, etc.) that you cannot find in the library catalog , use our interlibrary loan service .

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- EBSCOhost Databases This link opens in a new window Search 22 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. EBSCO databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Gale Databases This link opens in a new window Search over 35 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. Gale databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection This link opens in a new window Contains articles from nearly 560 scholarly journals, some dating as far back as 1965

- Access World News This link opens in a new window Search the full-text of editions of record for local, regional, and national U.S. newspapers as well as full-text content of key international sources. This is your source for The Modesto Bee from January 1989 to the present. Also includes in-depth special reports and hot topics from around the country. To access The Modesto Bee , limit your search to that publication. more... less... Watch this short video to learn how to find The Modesto Bee .

Use Google Scholar to find scholarly literature on the Web:

Browse Featured Web Sites:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA's mission is to lead the nation in bringing the power of science to bear on drug abuse and addiction. This charge has two critical components. The first is the strategic support and conduct of research across a broad range of disciplines. The second is ensuring the rapid and effective dissemination and use of the results of that research to significantly improve prevention and treatment and to inform policy as it relates to drug abuse and addiction.

- Drug Free America Foundation Drug Free America Foundation, Inc. is a drug prevention and policy organization committed to developing, promoting and sustaining national and international policies and laws that will reduce illegal drug use and drug addiction.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy A component of the Executive Office of the President, ONDCP was created by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. ONDCP advises the President on drug-control issues, coordinates drug-control activities and related funding across the Federal government, and produces the annual National Drug Control Strategy, which outlines Administration efforts to reduce illicit drug use, manufacturing and trafficking, drug-related crime and violence, and drug-related health consequences.

- Drug Policy Alliance The Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) is the nation's leading organization promoting alternatives to current drug policy that are grounded in science, compassion, health and human rights.

Your instructor should tell you which citation style they want you to use. Click on the appropriate link below to learn how to format your paper and cite your sources according to a particular style.

- Chicago Style

- ASA & Other Citation Styles

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/drugabuse

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

Search Issues

Vol. XXVIII, No. 4, Summer 2012

Eight Questions for Drug Policy Research

By Mark A. R. Kleiman , Jonathan P. Caulkins , Angela Hawken , Beau Kilmer

The current research agenda has only limited capacity to shrink the damage caused by drug abuse. Some promising alternative approaches could lead to improved results.

Drug abuse—of licit and illicit drugs alike—is a big medical and social problem and attracts a substantial amount of research attention. But the most attractive and most easily fundable research topics are not always those with the most to contribute to improved social outcomes. If the scientific effort paid more attention to the substantial opportunities for improved policies, its contribution to the public welfare might be greater.

The current research agenda around drug policy concentrates on the biology, psychology, and sociology of drugtaking and on the existing repertoire of drug-control interventions. But that repertoire has only limited capacity to shrink the damage that drug users do to themselves and others or the harms associated with drug dealing, drug enforcement, and drug-related incarceration; and the current research effort pays little attention to some innovative policies with substantial apparent promise of providing improved results.

At the same time, public opinion on marijuana has shifted so much that legalization has moved from the dreams of enthusiasts to the realm of practical possibility. Yet voters looking to science for guidance on the practicalities of legalization in various forms find little direct help.

All of this suggests the potential of a research effort less focused on current approaches and more attentive to alternatives.

The standard set of drug policies largely consists of:

- Prohibiting the production, sale, and possession of drugs

- Seizing illicit drugs

- Arresting and imprisoning dealers

- Preventing the diversion of pharmaceuticals to nonmedical use

- Persuading children not to begin drug use

- Offering treatment to people with drug-abuse disorders or imposing it on those whose behavior has brought them into conflict with the law

- Making alcohol and nicotine more expensive and harder to get with taxes and regulations

- Suspending the drivers’ licenses of those who drive while drunk and threatening them with jail if they keep doing it

With respect to alcohol and tobacco, there is great room or improvement even within the existing policy repertoire for example, by raising taxes), even before more-innovaive approaches are considered. With respect to the currently illicit drugs, it is much harder to see how increasing or slightly modifying standard-issue efforts will measurably shrink the size of the problems.

The costs—fiscal, personal, and social—of keeping half a million drug offenders (mostly dealers) behind bars are sufficiently great to raise the question of whether less comprehensive but more targeted drug enforcement might be the better course. Various forms of focused enforcement offer the promise of greatly reduced drug abuse, nondrug crime, and incarceration. These include testing and sanctions programs, interventions to shrink flagrant retail drug markets, collective deterrence directed at violent drug-dealing organizations, and drug-law enforcement aimed at deterring and incapacitating unusually violent individual dealers. Substantial increases in alcohol taxes might also greatly reduce abuse, as might developing more- effective treatments for stimulant abusers or improving the actual evidence base underlying the movement toward “evidence-based policies.”

These opportunities and changes ought to influence the research agenda. Surely what we try to find out should bear some relationship to the practical choices we face. Below we list eight research questions that we think would be worth answering. We have selected them primarily for policy relevance rather than for purely scientific interest.

1) How responsive is drug use to changes in price, risk, availability, and “normalcy”?

The fundamental policy question concerning any drug is whether to make it legal or prohibited. Although the choice s not merely binary, a fairly sharp line divides the spectrum of options. A substance is legal if a large segment of he population can purchase and possess it for unsupervised “recreational” use, and if there are no restrictions on who can produce and sell the drug beyond licensing and routine regulations.

Accepting that binary simplification, the choice becomes what kind of problem one prefers. Use and use-related problems will be more prevalent if the substance is legal. Prohibition will reduce, not eliminate, use and abuse, but with three principal costs: black markets that can be violent and corrupting, enforcement costs that exceed those of regulating a legal market, and increased damage per unit of consumption among those who use despite the ban. (Total use related harm could go up or down depending on the extent to which the reduction in use offsets the increase in harmfulness per unit of use.)

The costs of prohibition are easier to observe than are its benefits in the form of averted use and use-related problems. In that sense, prohibition is like investments in prevention, such as improving roads; it’s easier to identify the costs than to identify lives saved in accidents that did not happen.

We would like to know the long-run effect on consumption of changes in both price and the nonprice aspects of availability, including legal risks and stigma. There is now a literature estimating the price elasticity of demand for illegal drugs, but the estimates vary widely from one study to the next and many studies are based on surveys that may not give adequate weight to the heavy users who dominate consumption. Moreover, legalization would probably involve price declines that go far beyond the support of historical data.

Furthermore, as Mark Moore pointed out many years ago, the nonprice terms of availability, which he conceptualized as “search cost,” may match price effects in terms of their impact on consumption. Ye t those effects have never been quantitatively estimated for a change as profound as that from illegality to legality. The decision not to enforce laws against small cannabis transactions in the Netherlands did not cause an explosion in use; whether and how much it increased consumption and whether the establishment of retail shops mattered remain controversial questions.

This ignorance about the effect on consumption hamstrings attempts to be objective and analytical when discussing the question of whether to legalize any of the currently illicit drugs, and if so, under what conditions.

2) How responsive is the use of drug Y to changes in policy toward drug X?

Polydrug use is the norm, particularly among frequent and compulsive users. (Most users do not fall in that category, but the minority who do account for the bulk of consumption and harms.) Therefore, “scoring” policy interventions by considering only effects on the target substance is potentially misleading.

For example, driving up the price of one drug, say cocaine, might reduce its use, but victory celebrations should be tempered if the reduction stemmed from users switching to methamphetamine or heroin. On the other hand, school based drug-prevention efforts may generate greater benefits through effects on alcohol and tobacco abuse than via their effects on illegal drug use. Comparing them to other drug-control interventions, such as mandatory minimum sentences for drug dealers, in terms of ability to control illegal drugs alone is a mistake; those school-based prevention interventions are not (just) illicit-drug–control programs.

But policy is largely made one substance at a time. Drugs are added to schedules of prohibited substances based on their potential for abuse and for use as medicine. Reformers clamor for evidence-based policies that rank individual drugs’ harmfulness, as attempted recently by David Nutt, and ban only the most dangerous. Ye t it makes little practical sense to allow powder cocaine while banning crack, because anyone with baking soda and a microwave oven can convert powder to crack.

Considerations of substitution or complementarity ought to arise in making policy toward some of the so-called designer drugs. Mephedrone looks relatively good if most of its users would otherwise have been abusing methamphetamine; it looks terrible if in fact it acts as a stepping stone to methamphetamine use. But no one knows which is the case.

Marijuana legalization is in play in a way it has not been since the 1970s. Various authors have produced social-welfare analyses of marijuana legalization, toting up the benefits of reduced enforcement costs and the costs of greater need for treatment, accounting for potential tax revenues and the like.

Yet the marijuana-specific gains and losses from legalization would be swamped by the uncertainties concerning its effects on alcohol consumption. The damage from alcohol is a large multiple of the damage from cannabis; thus a 10% change, up or down, in alcohol abuse could outweigh any changes in marijuana-related outcomes.

There is conflicting evidence as to whether marijuana and alcohol are complements or substitutes; no one can rule out even larger increases or decreases in alcohol use as a result of marijuana legalization, especially in the long run.

Marijuana legalization might also influence heavy use of cocaine or cigarette smoking. But again, no one knows whether that effect would be to drive cocaine or cigarette use up or down, let alone by how much. If doubling marijuana use led to even a 1% increase or decrease in tobacco use, it could produce 4,000 more or 4,000 fewer tobacco related deaths per year, far more than the (quite small) number of deaths associated with marijuana.

This uncertainty makes it impossible to produce a solid benefit/cost analysis of marijuana legalization with existing data. That suggests both caution in drawing policy conclusions and aggressive efforts to learn more about cross-elasticities among drugs prone to abuse.

3) Can we stop large numbers of drug-involved criminal offenders from using illicit drugs?

Many county, state, and federal initiatives target drug use among criminal offenders. Ye t most do little to curtail drug use or crime. An exception is the drug courts process; some implementations of that idea have been shown to reduce drug use and other illegal behavior. Unfortunately, the resource intensity of drug courts limits their potential scope. The requirement that every participant must appear regularly before a judge for a status hearing means that a drug court judge can oversee fewer than 100 offenders at any time.

The HOPE approach to enforcing conditions of probation and parole, named after Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement, offers the potential for reducing use among drug-involved offenders at a larger scale. Like drug courts, HOPE provides swift and certain sanctions for probation violations, including drug use. HOPE starts with a formal warning that any violation of probation conditions will lead to an immediate but brief stay in jail. Probationers are then subject to regular random drug testing: six times a month at first, diminishing in frequency with sustained compliance. A positive drug test leads to an immediate arrest and a brief jail stay (usually a few days but in some jurisdictions as little as a few hours in a holding cell). Probationers appear before the judge only if they have violated a rule; in contrast, a drug court judge participates in every status review. Thus HOPE sites can supervise large numbers of offenders; a single judge in Hawaii now supervises more than 2,000 HOPE probationers.

In a large randomized controlled trial (RCT), Hawaii’s HOPE program greatly outperformed standard probation in reducing drug use, new crimes, and incarceration among a population of mostly methamphetamine-using felony probationers. A similar program in Tarrant County, Texas (encompassing Arlington and Fort Worth), appears to produce similar results, although this has not yet been verified by an RCT, as has a smaller-scale program (verified by an RCT) among parolees in Seattle. Reductions in drug use of 80%, in new arrests of 30 to 50%, and in days behind bars of 50% appear to be achievable at scale. The last result is the most striking; get-tough automatic-incarceration policies can reduce incarceration rather than increasing it, if the emphasis is on certainty and celerity rather than severity.

The Department of Justice is funding four additional RCTs; those results should help clarify how generalizable the HOPE outcomes are. But to date there has been no systematic experimentation to test how variations in program parameters lead to variations in results.

Hawaii’s HOPE program uses two days in jail as its typical first sanction. Penalties escalate for repeated violations, and the 15% or so of participants who violate a fourth time face a choice between residential treatment and prison. No one is mandated to undergo treatment except after repeated failures. The results suggest that this is an effective design, but is it optimal? Would some sanction short of jail for the first violation—a curfew, home confinement, or community service—work as well? Are escalating penalties necessary and if so, what is the optimal pattern of escalation? Is there a subset of offenders who ought to be mandated to treatment immediately rather than waiting for failures to accumulate? Should cannabis be included in the list of drugs tested for, as it is in Hawaii, or excluded? How about synthetically produced cannabinoids (sold as “Spice”) and cathinones (sold as “bath salts”), which require more complex and costly screening? Would adding other services to the mix improve outcomes? How can HOPE be integrated with existing treatment-diversion programs and drug courts? How can HOPE principles best be applied to parole, pretrial release, and juvenile offenders?

Answering these questions would require measuring the results of systematic variation in program conditions. There is no strong reason to think that the optimal program design will be the same in every jurisdiction or for every offender population. But it’s time to move beyond the question “Does HOPE work?” to consider how to optimize the design of testing-and-sanctions programs.

4) Can we stop alcohol-abusing criminal offenders from getting drunk?

Under current law, state governments effectively give every adult a license to purchase and consume alcohol in unlimited quantities. Judges in some jurisdictions can temporarily revoke that license for those with an alcohol-related offense by prohibiting drinking and going to bars as conditions of bail or probation. However, because alcohol passes through the body quickly, a typical random-but-infrequent testing regiment would miss most violations, making the revocation toothless.

In 2005, South Dakota embraced an innovative approach to this problem, called 24/7 Sobriety. As a condition of bail, repeat drunk drivers who were ordered to abstain from alcohol were now subject to twice-a-day breathalyzer tests, every day. Those testing positive or missing the test were immediately subject to a short stay in jail, typically a night or two. What started as a five-county pilot program expanded throughout the state, and judges began applying the program to offenders with all types of alcohol-related criminal behavior, not just drunk driving. Some jurisdictions even started using continuous alcohol-monitoring bracelets, which can remotely test for alcohol consumption every 30 minutes. Approximately 20,000 South Dakotans have participated in 24/7—an astounding figure for a state with a population of 825,000.

The anecdotal evidence about the program is spectacular; fewer than 1% of the 4.8 million breathalyzer tests ordered since 2005 were failed or missed. That is not because the offenders have no interest in drinking. About half of the participants miss or fail at least one test, but very few do so more than once or twice. 24/7 is now up and running in other states, and will soon be operating in the United Kingdom. As of yet there are no peer-reviewed studies of 24/7, but preliminary results from a rigorous quasi-experimental evaluation suggest that the program did reduce repeat drunk driving in South Dakota. Furthermore, as with HOPE, there remains a need to better understand for whom the program works, how long the effects last, the mechanism(s) by which it works, and whether it can be effective in a more urban environment.

Programs such as HOPE and 24/7 can complement traditional treatment by providing “behavioral triage.” Identifying which subset of substance abusers cannot stop drinking on their own, even under the threat of sanctions, allows the system to direct scarce treatment resources specifically to that minority.

Another way to take away someone’s drinking license would be to require that bars and package stores card every would be to require that bars and package stores card every buyer and to issue modified driver’s licenses with nondrinker markings on them to those convicted of alcohol-related crimes. This approach would probably face legal and political challenges, but that should not discourage serious analysis of the idea.

There is also strong evidence that increasing the excise tax on alcohol could reduce alcohol-related crime. Duke University economist Philip Cook estimates that doubling the federal tax, leading to a price increase of about 10%, would reduce violent crime and auto fatalities by about 3%, a striking saving in deaths for a relatively minor and easy-to-administer policy change. There is also evidence that formal treatment, both psychological and pharmacological, can yield improvements in outcomes for those who accept it.

There is also strong evidence that increasing the excise linked. Among people with drug problems who are also crimtax on alcohol could reduce alcohol-related crime. Duke Uni- inally active, criminal activity tends to rise and fall with drug versity economist Philip Cook estimates that doubling the consumption. Reductions in crime constitute a major benfederal tax, leading to a price increase of about 10%, would efit of providing drug treatment for the offender population, reduce violent crime and auto fatalities by about 3%, a strik- or of imposing HOPE-style community supervision. ing saving in deaths for a relatively minor and easy-to-ad- Reducing drug use among active offenders could also minister policy change. There is also evidence that formal shrink illicit drug markets, producing benefits everywhere, treatment, both psychological and pharmacological, can yield from inner-city neighborhoods wracked by flagrant drug improvements in outcomes for those who accept it.

5) How concentrated is hard-drug use among active criminals?

Literally hundreds of substances have been prohibited, but the big three expensive drugs (sometimes called the “hard” drugs)—cocaine, including crack; heroin; and methamphetamine— account for most of the societal harm. The serious criminal activity and other harms associated with those substances are further highly concentrated among a minority of their users. Many people commit a little bit of crime or use hard drugs a handful of times, but relatively few make a habit of either one. Despite their relatively small numbers, those frequent users and their suppliers account for a large share of all drug-related crime and violence.

The populations overlap; an astonishing proportion of those committing income-generating crimes, such as robbery, as opposed to arson, are drug-dependent and/or intoxicated at the time of their offense, and a large proportion of frequent users of expensive drugs commit income-generating crime. Moreover, the two sets of behaviors are causally linked. Among people with drug problems who are also criminally active, criminal activity tends to rise and fall with drug consumption. Reductions in crime constitute a major benefit of providing drug treatment for the offender population, or of imposing HOPE-style community supervision.

Reducing drug use among active offenders could also shrink illicit drug markets, producing benefits everywhere, from inner-city neighborhoods wracked by flagrant drug dealing to source and transit countries such as Colombia and Mexico.

A back-of-the envelope calculation suggests the potential size of these effects. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates users in the household population. The Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program measures the rate of active substance use among active offenders (by self-report and urinalysis). Two decades ago, an author of this article (Kleiman) and Chris Putala, then on the Senate Judiciary Committee staff, used the predecessors of those surveys to estimate that about three-quarters of all heavy (morethan-weekly) cocaine users had been arrested for a nondrug felony in the previous year.

Applying the Pareto Law’s rule of thumb that 80% of the volume of any activity is likely to be accounted for by about 20% of those who engage in it—true, for example, about the distribution of alcohol consumption—suggests that something like three-fifths of all the cocaine is used by people who get arrested in the course of a typical year and who are therefore likely to be on probation, parole, or pretrial release if not behind bars.

Combining that calculation with the result from HOPE that frequent testing with swift and certain sanctions can shrink (in the Hawaii case) methamphetamine use among heavily drug-involved felony probationers by 80%, suggests that total hard-drug volume might be reduced by something like 50% if HOPE-style supervision were applied to all heavy users of hard drugs under criminal-justice supervision. No known drug-enforcement program has any comparable capability to shrink illicit-market volumes.

By the same token, HOPE seems to reduce criminal activity, as measured by felony arrests, by 30 to 50%. If frequent offenders commit 80% of income-generating crime, and half of those frequent offenders also have serious harddrug problems, such a reduction in offending within that group could reduce total income-generating crime by approximately 15 to 20%, while also decreasing the number of jail and prison inmates.

The Kleiman and Putala estimate was necessarily crude because it was based on studies that weren’t designed to measure the concentration of hard-drug use among offenders. Unfortunately, no one in the interim has attempted to refine that estimate with more precise methods (for example, stochastic-process modeling) or more recent data.

6) What is the evidence for evidence-based practices?

Many agencies now recommend (and some states and federal grant programs mandate) adoption of prevention and treatment programs that are evidence-based. But the move toward evidence-based practices has one serious limitation: the quality of the evidence base. It is important to ask what qualifies as evidence and who gets to produce it. Many programs are expanded and replicated on the basis of weak evidence. Study design matters. A review by George Mason University Criminologist David Weisburd and colleagues showed that the effect size of offender programs is negatively related to study quality: The more rigorous the study is, the smaller its reported effects.

Who does the evaluation can also make a difference. Texas A&M Epidemiologist Dennis Gorman found that evaluations authored by program developers report much larger effect sizes than those authored by independent researchers. Yet Benjamin Wright and colleagues reported that more than half of the substance-abuse programs targeting criminal-justice programs that were designated as evidence-based on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) National Registry of Evidence Based Programs and Practices (NREPP) include the program developer as evaluator. Consequently, we may be spending large sums of money on ineffective programs. Many jurisdictions, secure in their illusory evidence base, could become complacent about searching for alternative programs that really do work.

We need to get better at identifying effective strategies and helping practitioners sort through the evidence. Requiring that publicly funded programs be evaluated and show improved outcomes using strong research designs—experimental designs where feasible, well-designed historicalcontrol strategies where experiments can’t be done, and “intent-to-treat” analyses rather than cherry-picking success by studying program completers only—would cut the number of programs designated as promising or evidence-based by more than 75%. Not only would this relieve taxpayers of the burden of supporting ineffective programs, it would also help researchers identify more promising directions for future intervention research.

The potential for selection biases when studying druginvolved people is substantial and thus makes experimental designs much more valuable. Small is key. It avoids expense, and equally important, it avoids champions with bruised egos. It is difficult to scale back a program once an agency becomes invested in the project. Small pilot evaluations that do show positive outcomes can then be replicated and expanded if the replications show similarly positive results.

7) What treats stimulant abuse?

Science can alleviate social problems not only by guiding policy but also by inventing better tools. The holy grail of such innovations would be a technology that addresses stimulant dependence.

The ubiquitous “treatment works” mantra masks a sharp disparity in technologies available for treating opiates (heroin and oxycodone) as opposed to stimulants (notably cocaine, crack, and meth). A variety of so-called opiate-substitute therapies (OSTs) exist that essentially substitute supervised use of legal, pure, and cheap opiates for unsupervised use of street opiates. Methadone is the first and best-known OST, but there are others. A number of countries even use clinically supplied heroin to substitute for street heroin.

OST stabilizes dependent individuals’ chaotic lives, with positive effects on a wide range of life outcomes, such as increased employment and reduced criminality and rates of overdose. Sometimes stabilization is a first step toward abstinence, but for better and for worse the dominant thinking since the 1980s has been to view substitution therapy as an open-ended therapy, akin to insulin for diabetics. Either way, OST consistently fares very well in evaluations that quantify social benefits produced relative to program costs.

There is no comparable technology for treating stimulant dependence. This is not for lack of trying. The National Institute on Drug Abuse has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in the quest for pharmacotherapies for stimulants. Decades of work have produced many promising advances in basic science, but with comparatively little effect on clinical practice. The gap between opiate and stimulant treatment technologies matters more in the United States and the rest of the Western Hemisphere, where stimulants have a large market, than in the rest of the world, where opiates remain predominant.

There are two reactions to this zero-for-very-many batting average. One is to redouble efforts; after all, Edison tried a lot of filament materials before hitting on carbonized bamboo. The other is to give up on the quest for a chemical that can offset, undo, or modulate stimulants’ effects in the brain and pursue other approaches. For example, immunotherapies are a fundamentally different technology inasmuch as the active introduced agent does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Rather, the antibodies act almost more like interdiction agents, but interdicting the drug molecules between ingestion and their crossing the blood-brain barrier rather than interdicting at the nation’s border.

There is evidence from clinical trials showing that some cognitive-behavioral therapies can reduce stimulant consumption for some individuals. Contingency management also takes a behavioral rather than a chemical approach, essentially incentivizing dependent users to remain abstinent. The stunning finding is that, properly deployed, very small incentives (for example, vouchers for everyday items) can induce much greater behavioral change than can conventional treatment methods alone.

The ability of contingency management to reduce consumption, and the finding that even the heaviest users respond to price increases by consuming less, profoundly challenge conventional thinking about the meaning of addiction. They seem superficially at odds with the clear evidence that addiction is a brain disease with a physiological basis. Brainimaging studies let us see literally how chronic use changes the brain in ways that are not reversed by mere withdrawal of the drugs. So just as light simultaneously displays characteristics of a particle and a wave, so too addiction simultaneously has characteristics of a physiological disease and a behavior over which the person has (at least limited) control.

8) What reduces drug-market violence?

Drug dealers can be very violent. Some use violence to settle disputes about territory or transactions; others use violence to climb the organizational ladder or intimidate witnesses or enforcement officials. Because many dealers have guns or have easy access to them, they also sometimes use these weapons to address conflicts that have nothing to do with drugs. Because the market tends to replace drug dealers who are incarcerated, there is little reason to think that routine drug-law enforcement can reduce violence; the opposite might even be true if greater enforcement pressure makes violence more advantageous to those most willing to use it.

That raises the question of whether drug-law enforcement can be designed specifically to reduce violence. One set of strategies toward this end is known as focused deterrence or pulling-levers policing. These approaches involve lawenforcement officials directly communicating a credible threat to violent individuals or groups, with the goal of reducing the violence level, even if the level of drug dealing or gang activity remains the same. Such interventions aim to tip situations from high-violence to low-violence equilibria by changing the actual and perceived probability of punishment; for example, by making violent drug dealing riskier, in enforcement terms, than less violent drug dealing.

The seminal effort was the Boston gun project Ceasefire, which focused on reducing juvenile homicides in the mid-1990s. Recognizing that many of the homicides stemmed from clashes between juvenile gangs, the strategy focused on telling members of each gang that if anyone in the gang shot someone (usually a member of a rival gang) police and prosecutors would pull every lever legally available against the entire gang, regardless of which individual had pulled the trigger. Instead of receiving praise from colleagues for increasing the group’s prestige, the potential shooter now had to deal with the fact that killing put the entire group at risk. Thus the social power of the gang was enlisted on the side of violence reduction. The results were dramatic: Youth gun homicides in Boston fell from two a month before the intervention to zero while the intervention lasted. Variants of Ceasefire have been implemented across the country, some with impressive results.

An alternative to the Ceasefire group-focused strategy is a focus on specific drug markets where flagrant dealing leads to violence and disorder. Police and prosecutors in High Point, North Carolina, adopted a focused-deterrence approach, which involved strong collaborations with community members. Their model, referred to as the Drug Market Intervention, involved identifying all of the dealers in the targeted market, making undercover buys from them (often on film), arresting the most violent dealers, and not arresting the others. Instead, the latter were invited to a community meeting where they were told that, although cases were made against them, they were going to get another chance as long as they stopped dealing. The flagrant drug market in that neighborhood, as David Kennedy reports, vanished literally overnight and has not reappeared for the subsequent seven years. The program has been replicated in dozens of jurisdictions, and there is a growing evidence base showing that it can reduce crime.

A third approach recognizes the heterogeneity in violence among individual drug dealers. By focusing enforcement on those identified as the most violent, police can create both Darwinian and incentive pressures to reduce the overall violence level. This technique has yet to be systematically evaluated. This seems like an attractive research opportunity if a jurisdiction wants to try out such an approach.

An especially challenging problem is dealing-related violence in Mexico, now claiming more than 1,000 lives per month. It is worth considering whether a Ceasefire-style strategy might start a tipping process toward a less violent market. Such a strategy could exploit two features of the current situation: The Mexican groups make most of their money selling drugs for distribution in the United States, and the United States has much greater drug enforcement capacity than does Mexico. If the Mexican government were to select one of the major organizations and target it for destruction after a transparent process based on relative violence levels, U.S. drug-law enforcement might be able to put the target group out of business by focusing attention on the U.S. distributors that buy their drugs from the target Mexican organization, thereby pressuring them to find an alternative source. If that happened, the target organization would find itself without a market for its product.

If one organization could be destroyed in this fashion, the remaining groups might respond to an announcement that a second selection process was underway by competitively reducing their violence levels, each hoping that one of its rivals would be chosen as the second target. The result might be—with the emphasis on might—a dramatic reduction in bloodshed.

Whatever the technical details of violence-minimizing drug-law enforcement, its conceptual basis is the understanding that in established markets enforcement pressure can have a greater effect on how drugs are sold than on how much is sold. So violence reduction is potentially more feasible than is greatly reducing drug dealing generally.

Drug policy involves contested questions of value as well as of fact; that limits the proper role of science in policymaking. And many of the factual questions are too hard to be solved with the current state of the art: The mechanisms of price and quantity determination in illicit markets, for example, have remained largely impervious to investigation. Conversely, research on drug abuse can provide insight into a variety of scientifically interesting questions about the nature of human motivation and self-regulation, complicated by imperfect information, intoxication, and impairment, and engaging group dynamics and tipping phenomena; not every study needs to be justified in terms of its potential contribution to making better policy. However, good theory is often developed in response to practical challenges, and policymakers need the guidance of scientists. Broadening the current research agenda away from biomedical studies and evaluations of the existing policy repertoire could produce both more interesting science and more successful policies.

Join the Conversation

Sign up for the Issues in Science and Technology newsletter to get the latest policy insights delivered direct to your inbox. When you do, you'll receive a special offer for nearly 50% off a one-year subscription to the magazine—or simply subscribe now at this special rate .

- Name * First Last

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Signs of Addiction

Addiction Research

Discover the latest in addiction research, from the neuroscience of substance use disorders to evidence-based treatment practices. reports, updates, case studies and white papers are available to you at hazelden betty ford’s butler center for research..

Why do people become addicted to alcohol and other drugs? How effective is addiction treatment? What makes certain substances so addictive? The Butler Center for Research at the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation investigates these and other questions and publishes its scientific findings in a variety of alcohol and drug addiction research papers and reports. Research topics include:

- Evidence-based treatment practices

- Addiction treatment outcomes

- Addiction, psychiatry and the brain

- Addictive substances such as prescription opioids and heroin

- Substance abuse in youth/teens, older adults and other demographic groups such as health care or legal professionals

These research queries and findings are presented in the form of updates, white papers and case studies. In addition, the Butler Center for Research collaborates with the Recovery Advocacy team to study special-focus addiction research topics, summarized in monthly Emerging Drug Trends reports. Altogether, these studies provide the latest in addiction research for anyone interested in learning more about the neuroscience of addiction and how addiction affects individuals, families and society in general. The research also helps clinicians and health care professionals further understand, diagnose and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Learn more about each of the Butler Center's addiction research studies below.

Research Updates

Written by Butler Center for Research staff, our one-page, topic-specific summaries discuss current research on topics of interest within the drug abuse and addiction treatment field.

View our most recent updates, or view the archive at the bottom of the page.

Patient Outcomes Study Results at Hazelden Betty Ford

Trends and Patterns in Cannabis Use across Different Age Groups

Alcohol and Tobacco Harm Reduction Interventions

Harm Reduction: History and Context

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities and Addiction

Psychedelics as Therapeutic Treatment

Sexual and Gender Minority Youth and SUDs

Health Care Professionals and Mental Health

Grief and Addiction

Helping Families Cope with Addiction

Emerging Drug Trends Report and National Surveys

Shedding New Light on America’s No. 1 Health Problem

In collaboration with the University of Maryland School of Public Health and with support from the Butler Center for Research, the Recovery Advocacy team routinely issues research reports on emerging drug trends in America. Recovery Advocacy also commissions national surveys on attitudes, behaviors and perspectives related to substance use. From binge drinking and excessive alcohol use on college campuses, to marijuana potency concerns in an age of legalized marijuana, deeper analysis and understanding of emerging drug trends allows for greater opportunities to educate, inform and prevent misuse and deaths.

Each drug trends report explores the topic at hand, documenting the prevalence of the problem, relevant demographics, prevention and treatment options available, as well as providing insight and perspectives from thought leaders throughout the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.

View the latest Emerging Drug Trends Report:

Pediatricians First Responders for Preventing Substance Use

- Clearing Away the Confusion: Marijuana Is Not a Public Health Solution to the Opioid Crisis

- Does Socioeconomic Advantage Lessen the Risk of Adolescent Substance Use?

- The Collegiate Recovery Movement Is Gaining Strength

- Considerations for Policymakers Regarding Involuntary Commitment for Substance Use Disorders

- Widening the Lens on the Opioid Crisis

- Concerns Rising Over High-Potency Marijuana Use

- Beyond Binging: “High-Intensity Drinking”

View the latest National Surveys :

- College Administrators See Problems As More Students View Marijuana As Safe

College Parents See Serious Problems From Campus Alcohol Use

- Youth Opioid Study: Attitudes and Usage

About Recovery Advocacy

Our mission is to provide a trusted national voice on all issues related to addiction prevention, treatment and recovery, and to facilitate conversation among those in recovery, those still suffering and society at large. We are committed to smashing stigma, shaping public policy and educating people everywhere about the problems of addiction and the promise of recovery. Learn more about recovery advocacy and how you can make a difference.

Evidence-Based Treatment Series

To help get consumers and clinicians on the same page, the Butler Center for Research has created a series of informational summaries describing:

- Evidence-based addiction treatment modalities

- Distinctive levels of substance use disorder treatment

- Specialized drug and alcohol treatment programs

Each evidence-based treatment series summary includes:

- A definition of the therapeutic approach, level of care or specialized program

- A discussion of applicability, usage and practice

- A description of outcomes and efficacy

- Research citations and related resources for more information

View the latest in this series:

Motivational Interviewing

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Case Studies and White Papers

Written by Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation researchers and clinicians, case studies and white papers presented by the Butler Center for Research provide invaluable insight into clinical processes and complex issues related to addiction prevention, treatment and recovery. These in-depth reports examine and chronicle clinical activities, initiatives and developments as a means of informing practitioners and continually improving the quality and delivery of substance use disorder services and related resources and initiatives.

- What does it really mean to be providing medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction?

Adolescent Motivational Interviewing

Peer Recovery Support: Walking the Path Together

Addiction and Violence During COVID-19

The Brain Disease Model of Addiction

Healthcare Professionals and Compassion Fatigue

Moving to Trauma-Responsive Care

Virtual Intensive Outpatient Outcomes: Preliminary Findings

Driving Under the Influence of Cannabis

Vaping and E-Cigarettes

Using Telehealth for Addiction Treatment

Grandparents Raising Grandchildren

Substance Use Disorders Among Military Populations

Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

Women and Alcohol

Prescription Rates of Opioid Analgesics in Medical Treatment Settings

Applications of Positive Psychology to Substance Use Disorder

Substance Use Disorders Among Legal Professionals

Factors Impacting Early Alcohol and Drug Use Among Youths

Animal-Assisted Therapy for Substance Use Disorders

Prevalence of Adolescent Substance Misuse

Problem Drinking Behaviors Among College Students

The Importance of Recovery Management

Substance Use Factors Among LGBTQ individuals

Prescription Opioids and Dependence

Alcohol Abuse Among Law Enforcement Officers

Helping Families Cope with Substance Dependence

The Social Norms Approach to Student Substance Abuse Prevention

Drug Abuse, Dopamine and the Brain's Reward System

Women and Substance Abuse

Substance Use in the Workplace

Health Care Professionals: Addiction and Treatment

Cognitive Improvement and Alcohol Recovery

Drug Use, Misuse and Dependence Among Older Adults

Emerging Drug Trends

Does Socioeconomic Advantage Lessen the Risk of Adolescent Substance Use

The Collegiate Recovery Movement is Gaining Strength

Involuntary Commitment for Substance Use Disorders

Widening the Lens of the Opioid Crisis

Beyond Binge Drinking: High Intensity Drinking

High Potency Marijuana

National Surveys

College Administrators See Problems as More Students View Marijuana as Safe

Risky Opioid Use Among College-Age Youth

Case Studies/ White Papers

What does it really mean to be providing medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction

Are you or a loved one struggling with alcohol or other drugs? Call today to speak confidentially with a recovery expert. Most insurance accepted.

Harnessing science, love and the wisdom of lived experience, we are a force of healing and hope for individuals, families and communities affected by substance use and mental health conditions..

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

An Exploration of Student Attitudes towards Illicit Drug Use: A Normalisation Perspective

While a great deal of research has examined students’ attitudes towards illicit drug use in America, little academic literature has focused on students attitudes towards illicit drug use. Therefore this dissertation was a small exploratory study into student attitudes towards illicit drug use. Thus, the primary question which was addressed in the research was ‘what are student attitudes towards illicit drug use?’ This question was examined in relation to Parker et al’s. (2002) five dimensions of normalisation, to explore whether students at Glasgow University held normative attitudes towards illicit drug use. A sub question of this research project was what illicit drugs (if any) have been normalised according to Parker et al’s. (2002) theory. The research involved utilising the method of vignettes in a semi-structured interview setting, to gain information on students’ attitudes towards illicit drug use. Hence, 11 students within the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University were interviewed. The findings from this research supported Parker et al’s. (2002) theory as students seemed to hold normative attitudes to some drugs. The drugs which students seemed to hold normative attitudes towards were: cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy and study aids. However, the research did find a number of differences from Parker et al’s. (2002) theory, and thus builds on Parker et al’s. (2002) original theory by arguing there are only four dimensions of normalisation and both young people and adults hold normative attitudes not just young people as Parker et al. (2002) suggested. Therefore this dissertation concludes that it seems that students within the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University hold normative attitudes towards some illicit drugs.

Related Papers

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health

Jeanette Ostergaard

Aims: Previous studies indicate that young people who have positive attitudes towards illicit drugs are more inclined to experiment with them. The first aim of our study was to identify the sociodemographic and risk behaviour characteristics of young people (16–24 years) with positive attitudes towards illicit drug use. The second aim was to identify the characteristics of young people with positive attitudes towards illicit drugs among those who had never tried drugs, those who had tried cannabis but no other illicit drugs, and those who regularly used cannabis and/or had tried other illicit drugs. Methods: The analysis was based on a population-based survey from 2013 ( N = 3812). Multiple logistic regression was used to analyse the association between sociodemographic and risk behaviour characteristics and positive attitudes towards illicit drugs. Results: Young men had twice the odds of having positive attitudes towards illicit drug use compared with young women (AOR = 2.1). Also...

Drugs: education, prevention and policy

Christopher Wibberley

William Sedlacek

Dr Brian McMillan

Substance Use & Misuse

François Beck

Australian Journal of Public Health

Catherine Spooner

William Sedlacek , Lydia Minatoya

International Journal of Drug Policy

Hilary Pilkington

Judith Aldridge

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Drugs: Education, Policy, Prevention

Kat Kolar , Geraint Osborne

Drug and Alcohol Dependence

Christopher Spencer

Sharon Pienaar

Education Sciences

Susana Vidigal Alfaya

International Journal on Disability and Human Development

Susan Rasmussen

Manju Khokhar and Bhagat Singh

Bhagat Singh

Preventive Medicine

Yıldız Akvardar

Comprehensive Psychiatry

Margaret Linn

Teresa Whitaker , Pearl Treacy

Alan Peter Rogers

Sociology-the Journal of The British Sociological Association

Lisa Williams

Elizaveta Berezina

International Journal of Advanced Research

Jane A FISCHER

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology

Emilio J . Sanz

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 28 May 2022

A qualitative study exploring how young people perceive and experience substance use services in British Columbia, Canada

- Roxanne Turuba 1 , 2 ,

- Anurada Amarasekera 1 , 2 ,

- Amanda Madeleine Howard 1 , 2 ,

- Violet Brockmann 1 , 2 ,

- Corinne Tallon 1 , 2 ,

- Sarah Irving 1 , 2 ,

- Steve Mathias 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Joanna Henderson 6 , 7 ,

- Kirsten Marchand 1 , 4 , 5 , 8 &

- Skye Barbic 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 8

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 17 , Article number: 43 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

11 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Substance use among youth (ages 12–24) is troublesome given the increasing risk of harms associated. Even more so, substance use services are largely underutilized among youth, most only accessing support when in crisis. Few studies have explored young people’s help-seeking behaviours to address substance use concerns. To address this gap, this study explored how youth perceive and experience substance use services in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Participatory action research methods were used by partnering with BC youth (under the age of 30) from across the province who have lived and/or living experience of substance use to co-design the research protocol and materials. An initial focus group and interviews were held with 30 youth (ages 12–24) with lived and/or living experience of substance use, including alcohol, cannabis, and illicit substances. The discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically using a data-driven approach.

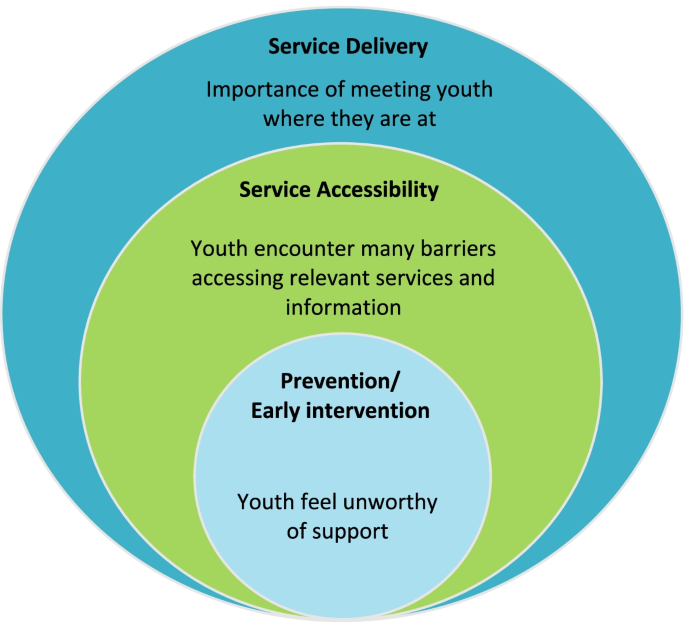

Three main themes were identified and separated by phase of service interaction, starting with: Prevention/Early intervention , where youth described feeling unworthy of support; Service accessibility , where youth encountered many barriers finding relevant substance use services and information; and Service delivery , where youth highlighted the importance of meeting them where they are at, including supporting those who have milder treatment needs and/or do not meet the diagnosis criteria of a substance use disorder.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a clear need to prioritize substance use prevention and early interventions specifically targeting youth and young adults. Youth and peers with lived and/or living experience should be involved in co-designing and co-delivering such programs to ensure their relevance and credibility among youth. The current disease model of care leaves many of the needs of this population unmet, calling for a more integrated youth-centred approach to address the multifarious concerns linked to young people’s substance use and service outcomes and experiences.

Substance use initiation is common during adolescence and young adulthood [ 1 ]. In North America, youth (defined here as aged 12–24) report the highest prevalence of substance use compared to older age groups [ 2 , 3 ], alcohol being the most common (youth 15–19: 57%; youth 20–24: 83%), followed by cannabis (youth 15–19: 19%; youth 20–24: 33%), and illicit substances (youth 15–19: 4%; youth 20–24: 10%) [ 2 ]. High rates of substance use among youth are worrisome given the ample evidence linking early onset to an increased risk of developing a substance use disorder (SUD) and further mental health and psychosocial problems [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Youth are also more likely to use more heavily and in riskier ways than adults, making them especially vulnerable to substance use related harms [ 2 , 7 ]. For example, polysubstance use is more common and increasing among youth [ 8 , 9 , 10 ], which has been associated with an increase in youth overdose hospitalizations [ 11 ]. Substance use is also associated with several leading causes of death among youth (e.g., suicide, unintentional injury, violence) [ 12 , 13 ], demonstrating an urgent need to provide effective substance use services to this population.

Current evidence-based recommendations to address substance use issues among youth include a range of comprehensive services, including family-oriented treatments, behavioural therapy, harm reduction services, pharmacological treatments, and long-term recovery services [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Like with adults, these services should be tailored based on young people’s individual needs and circumstances and should consider concurrent mental health disorders which are common among youth who use substances [ 3 , 15 , 18 ]. Merikangas et al. [ 18 ] reported rates of co-occurring mental health disorders as high as 77% among a community sample of youth with a SUD diagnosis. Regardless of precedence, both mental health and SUD can have exacerbating effects on each other if not treated, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and early access to care [ 19 ]. However, current practices utilizing an integrative approach to diagnose and treat SUD and concurrent mental health disorders have yet to be widely implemented [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Further, the current substance use service landscape has been largely designed to treat SUD in adult populations [ 17 ], who often require more intensive treatment compared to youth [ 15 ].

Literature suggests that there are differences between how youth and adults perceive and present substance use issues, suggesting different approaches may be needed to address substance use concerns [ 15 ]. For example, youth have shorter substance use histories and therefore often express fewer negative consequences related to their substance use, which may reduce their perceived need for services [ 15 ]. Further, the normalization of substance use among younger populations and the influence of peers and family members may also play a factor in reducing young people’s ability to recognize problems that arise due to their substance use [ 9 , 23 ]. Confidentiality concerns may also prevent youth from accessing services when needed [ 23 ]. Youth are therefore unlikely to access substance use services before they are in crisis. The 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [ 24 ] reported that only 7.2% of youth ages 12–25 who were identified as needing specialized substance use treatment (defined as substance use treatment received at a hospital (inpatient), rehabilitation facility (inpatient or outpatient), or a mental health centre) accessed appropriate services and that 92% of youth did not feel they needed to access specialized services for substance use. In 2020, the percentage of youth who received specialized treatment dropped to 3.6 and 98% of youth did not perceive the need for it [ 3 ], demonstrating the exacerbating effects the pandemic has had on young people’s service trajectory and experiences.

Although help-seeking behaviours to address mental health concerns among youth have been explored [ 25 , 26 ], few studies have been specifically designed to explore young people’s experiences with substance use services. Existing evidence has largely focused on the experiences of street entrenched youth and youth who specifically use illicit substances (e.g., opioids, heroin, fentanyl) ([ 1 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ], (Marchand K, Fogarty O, Pellat KM, Vig K, Melnychuk J, Katan C, et al: “We need to build a better bridge”: findings from a multi-site qualitative analysis of opportunities for improving opioid treatment services for youth, Under review)), which remains an important research focus, but may not be representative of those who have milder treatment needs. As such, this qualitative study aims to understand how youth perceive and experience substance use services in British Columbia (BC) more broadly. This study also explored young people’s recommendations to improving current models of care to address substance use concerns.

Study design & setting

This study is part of the Building capacity for early intervention: Increasing access to youth-centered, evidence-based substance use and addictions services in BC and Ontario project, which aims to create youth-informed substance use training for peer support workers and other service providers working within an integrated care model. The project is being led by Foundry Central Office and the Youth Wellness Hubs Ontario (YWHO), two youth integrated health service hubs in BC and Ontario respectively. As part of this project, the BC project team conducted a qualitative research study, entitled The Experience Project , to support the development of substance use training. This paper focuses on this BC study, which follows standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) [ 31 ].

In May 2020, we applied participatory action research (PAR) methods [ 32 , 33 ], by partnering with 14 youth (under the age of 30) throughout the course of the project, who had lived and/or living experience of substance use and lived in BC. Youth advisors were recruited through social media and targeted outreach (i.e., advisory councils from Indigenous-led organizations and rural and remote communities) in order to engage a diverse group of young people. A full description of our youth engagement methods has been described elsewhere (Turuba R, Irving S, Turnbull H, Howard AM, Amarasekera A, Brockmann V, et al: Practical considerations for engaging youth with lived and/or living experience of substance use as youth advisors and co-researchers, Under review). British Columbia has a population of approximately 4.6 million people, 88% of which reside within a metropolitan area; only 12% live in rural and remote communities across a vast region of land. Nationally, BC has been disproportionately impacted by the opioid crisis, counting 1782 illicit drug overdose deaths in 2021 alone, 84% of which were due to fentanyl poisoning [ 34 ]. Although more than half of BC’s population reside in the Metro Vancouver area, rates of illicit drug overdose deaths are similar across all health regions [ 34 ].

The youth partners formed a project advisory which co-created and revised the research protocol and materials. The initial focus group questions were informed by Foundry’s Clinician Working Group, based on what Foundry clinicians wanted to know about youth who use substances and how best to support them. The subsequent interview guide was developed based on the focus group learnings and debriefing sessions with the project youth advisory (see Data Collection section below). Three advisory members were also hired as youth research assistants to support further research activities including data collection, transcription, and analysis.

Participants

Participants were defined as youth between the ages of 12–24 who had lived and/or living experience of substance use (including alcohol, cannabis, and/or illicit substance use) in their lifetime and lived in BC. Substance use service experience was not a requirement as we wanted to understand young people’s perception of services and barriers to accessing them. Youth were recruited through Foundry’s social media pages and targeted advertisements. Organizations serving youth across the province were contacted about the study and asked to share recruitment adverts with youth clients. Organizations were identified by our youth advisors and Foundry service teams from across the province in order to recruit a geographically diverse sample of youth. This included mental health services, child and family services, social services, crisis centres, youth shelters, harm reduction services, treatment centres, substance use research partners, community centres, friendship centres, schools, and youth advisories. Interested youth contacted the research coordinator (author RT) to confirm their eligibility. Youth under the age of 16 required consent from a parent or legal guardian and gave their assent in order to participate, while youth ages 16–24 consented on their own behalf. Verbal consent was obtained from participants/legal guardians over the phone or Zoom after being read the consent form, prior to the focus group/interview. A hard copy of their consent form was signed by the research coordinator and sent to the participant/legal guardian for their records.

Data collection

Data collection began in November 2020 until April 2021. An initial semi-structured 2-h focus group with 3 youth (ages 16–24) was facilitated by 2 trained research team members, including a youth research assistant with lived/living experience. A peer support worker was also available for further support. The focus group discussion highlighted youth participants’ multifarious experiences with substance use services and the variety of substances used, which led us to change our data collection methods to individual in-depth interviews. Two interview guides were developed based on the focus group learnings to reflect the different range of service experiences. Interviews questions were reviewed and modified with the project youth advisory. Semi-structured interviews were held with 27 youth participants, which were facilitated by 1–2 members of the research team and lasted 30-min to an hour. In an effort to promote a safe and inclusive space for youth to share their experiences, participants were given the option to request a focus group/interview facilitator who identified as a person of color if preferred. The focus group/interviews began with introductions and the development of a community agreement to ensure youth felt safe to share their experiences. Participants were also sent a demographic survey to fill out prior to the focus group/interview, which was voluntary and not a requirement for participating in the qualitative focus group/interview. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the discussions were conducted virtually over Zoom. Participants were provided with a $30 or $50 honoraria for taking part in an interview or focus group, respectively.

Data analysis

The focus group and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically using NVivo (version 12) following an inductive approach using Braun and Clarke’s six step method [ 35 ]. The research coordinator led the analysis and debriefed regularly with author KM, who has extensive experience with qualitative health research in substance use [ 36 , 37 ]. The transcripts were read multiple times and initial memos were taken. A data driven approach was used to generate verbatim codes and identify themes. Meetings were also held with the youth research assistants to discuss the data and review and refine the themes to strengthen the credibility and validity of the findings, given their role as facilitators and their lived/living experience with substance use. This included selecting supporting quotes to highlight in the manuscript and conference presentations.

We interviewed a total of 30 youth participants. Socio-demographics, substance use patterns and service experiences are listed in Table 1 . Participants’ median age was 21 and primarily identified as women (55.6%) and white/Caucasian (66.7%). Most youth had used multiple substances in their lifetime and over the past 12-months, with alcohol being the most common, followed by marijuana/cannabis, psychedelics, amphetamines (e.g., MDMA, ecstasy) and other stimulants, non-prescription or illicit opioids, depressants, and inhalants. More than half (55.6%) had some post-secondary education and almost all participants were either in school and/or employed (94.4%). Seventy-five percent of participants had experience accessing substance use services.

Three overarching themes of youths’ substance use service perceptions and experiences were identified (see Fig. 1 ). These themes were specific to the phase of service interaction youth described, given that they were all at different phases of their substance use journeys and had different levels of interaction with substance use services. For example, some youth had never accessed substance use services but described their perceptions of services based on the information available to them, while others described specific service interactions they had. The themes were therefore separated by phase of service interaction, starting with 1. Prevention/Early intervention, where youth describe feeling unworthy of support; 2. Service accessibility, where youth encounter many barriers finding relevant services and information; and 3. Service delivery, where youth highlight the importance of meeting them where they are at.

Overarching themes describing young people’s experiences with substance use services

Prevention/early intervention: youth feel unworthy of support

Many youth described feeling unworthy of health and social services, especially when they did not identify as having a SUD. Young people’s perception of SUD typically revolved around the use of “ harder substances”, which participants defined as heroin, crack cocaine, intravenous drugs, and being in crisis situations, such as being homeless or at risk of an overdose. Youth perceived that most services were geared towards this population and therefore not for them. Many described suffering from “ imposter syndrome ” fearing that they would be taking space away from others who needed it more or judged by services providers for accessing services they did not ‘need’: