Humanistic Theory of Personality: Definition And Examples

Sourabh Yadav (MA)

Sourabh Yadav is a freelance writer & filmmaker. He studied English literature at the University of Delhi and Jawaharlal Nehru University. You can find his work on The Print, Live Wire, and YouTube.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

The humanistic theory of personality posits that humans have an innate drive toward self-actualization , as long as they are surrounded by the right environment.

It was developed by Carl Rogers, whose work (along with that of Abraham Maslow) helped establish the humanistic school of psychology. Unlike psychoanalysis or behaviorism, the humanistic school tries to take into account the entirety of the human experience.

For example, in clinical therapy, humanistic psychologists give centrality to the client’s experiences and try to provide a positive atmosphere to help them grow. Let us discuss the concept in more detail and then look at some examples.

Humanistic Theory of Personality Definition

The humanistic theory of personality was developed by Carl Rogers, largely in response to Freud’s personality theory , with which he strongly disagreed. He believed that:

“Experience is for me, the highest authority. . . . Neither the Bible nor the prophets—neither Freud nor research—neither the revelations of God nor man—can take precedence over my own experience”. (Rogers, 1961)

During the 1950s and 60s, behaviorism and psychoanalysis were the two most prominent schools of psychology. But the behaviorists used the techniques of natural sciences, which reduced humans to animals or machines.

Psychoanalysts, on the other hand, only focused on abnormal people. As such, a new group of psychologists (led by Abraham Maslow) created the humanistic school of psychology, which tried to give a fuller account of humans.

Humanistic psychology :

“recognizes his [a human’s] status as a person, irreducible to more elementary levels, and his unique worth as a being potentially capable of autonomous judgment and action.” (Kinget, 1975)

For Carl Rogers, the most important thing was to understand how a person viewed the world—their “subjective reality”. This led him to develop his humanistic theory of personality, which argued that all humans are innately driven to pursue their innermost feelings.

However, most people are actually unable to pursue this self-actualization because of the surrounding environment. What people need are relationships that provide “unconditional positive regard”, which helps us become fully functioning humans and reach our potential.

Humanistic Theory of Personality Examples

- Client-Centered Therapy: One of the biggest contributions of the humanistic theory of personality was its influence on therapy. While Rogers was pursuing his doctorate, most psychologists were trained in the psychoanalytic tradition. But Rogers realized that psychoanalysis had severe limitations, so he created his brand of client-centric therapy, based on the central belief that “the client who knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been deeply buried” (1961). Unlike psychoanalysts, Rogers did not call his disturbed individuals “patients”. Instead, he referred to them as “clients”, made an active attempt to understand their subjective reality, and then provided a positive therapeutic atmosphere.

- Q-Technique: While working as a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, Rogers and his colleagues attempted to create the first method of objectively measuring therapy’s effectiveness. This was the Q-technique (also known as the Q-sort technique), which was originally developed by William Stephenson. Rogers’ method involved having clients describe themselves in the present (real self) and then as they would like to become (ideal self). The two selves are then measured to determine the correlation between them. As the therapy progresses, the correlation between the two would become larger. So, it helps us to measure the effectiveness of therapy at any point during or after it. (Rogers, 1954).

- Education: Humanistic psychology believes in seeing every human being as a unique individual, and this idea has played a huge influence on modern education. Rogers saw traditional schools as bureaucratic institutions that were resistant to change. He instead advocated a “student-centric” approach to education, where students would take charge and develop their learning paths. Today, this idea is brought to reality in open classrooms, where the students are self-directed, choosing what and how they should study. The teachers act as facilitators, who provide the right atmosphere and support for individual learning journeys. In the United Kingdom, A.S. Neill founded the Summerhill School, built on many of these humanistic ideas.

- Understanding Parenthood & Relationships: Besides professional therapy or education, the humanistic theory of personality can also help us understand and improve our relationships. Like Maslow, Rogers believed that humans have an innate drive toward self-actualization. However, most people do not live according to their innermost feelings because of the childhood need for positive regard. If children are not loved unconditionally, they develop “conditions of worth”, that is, they learn to act in certain ways to be loved, which continues into adulthood. Rogers says that to remedy this, a person needs “unconditional positive regard”—to be loved for what they are—and this helps them become a “fully functioning person”.

- Career Guidance: The humanistic theory of personality can help us direct the overall path of our lives. Both Maslow and Rogers believe that humans are naturally driven toward self-actualization. For Rogers, this can happen when we are surrounded by loving people (who provide “unconditional positive regard”) and pursue our innermost feelings. Rogers calls it the “organismic valuing process”, which allows us to live fulfilling lives and reach our full potential. Like existentialism, humanistic psychology tells us to not worry about the conventions imposed upon us by society but to build our values and pursue them.

- Gestalt Therapy: Gestalt therapy was developed as a humanistic psychotherapy, and it is built around the idea that people are influenced by their present environment. So, instead of delving too much into past experiences, gestalt therapy focuses on the present moment, and it tries to improve the client’s awareness, freedom, and self-direction. Developed by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls, and Paul Goodman, the therapy tries to use empathy and unconditional acceptance to help an individual achieve personal growth and balance . The goal is to help people accept and trust what they feel.

So far, we have looked at the applications of the humanistic theory of personality. Let us now discuss some real-world instances related to it:

- Abraham Lincoln: Unlike other psychologists of his time, Maslow studied successful people, one of whom was the 16th President of the United States. Maslow found out that individuals like Lincoln were rarely concerned with other people’s judgments of them. Instead, they were focused on one central problem and spent their entire lives trying to solve it. So, successful people are deeply concerned with self-actualization, and the humanistic theory of personality also advocates doing that.

- A Bank Robber: Let us now talk about a completely contrasting instance: a criminal. If humanistic psychologists believe that all humans are innately good, then what about a bank robber? The answer is that, while humans have free will (they can act according to their wishes), they are also influenced by their environment. In this case, the surrounding conditions (monetary issues, proximity to other criminals, etc.) are what turn an individual into a criminal.

- Working Towards Promotion: In our professional careers, we all try to move upwards or achieve what is known as self-actualization. For example, you might work very hard to get more clients for your company, which would allow you to gain workplace incentives and perhaps eventually a promotion. So, our actions are driven by our desire to reach our full potential, which is what humanistic psychology believes.

- Tipping Behavior: The humanistic theory of personality also suggests that we wish to have “ congruence ” between our “ideal self” and “real self”. Incongruence can lead to mental distress (say anxiety), therefore we try hard to maintain our self-concept. For example, suppose you ate at a restaurant with a friend, and they felt that your tip was not sufficient. You may defend yourself by saying that the tip was in line with the service, which would allow you to maintain your self-concept of generosity & fairness.

Humanistic Approach to Personality’s Strengths & Weaknesses

While the humanistic theory of personality provided a way of studying the “whole person”, it is also often criticized for being unscientific.

During the 1950s and 60s, humanistic psychology began as a protest against behaviorism . This new group of psychologists argued that behaviorism concentrated on trivial behavior and ignored the emotional processes that make humans unique. (Hergenhahn, 2000).

They also critiqued psychoanalysis, arguing that it focused only on abnormal individuals and emphasized sexual/unconscious motivation; it ignored healthy individuals whose primary motives are personal growth and the improvement of society.

Furthermore, they highlight the flaws of the trait theory of personality , which tended to think personality traits – such as self-esteem – are innate rather than developed through environmental and social factors .

Humanistic psychology provided an alternative way of studying humans, which took into account the “wholeness” of a person, instead of merely looking at certain behaviors or unconscious motivations.

However, humanistic psychology has also been criticized by many scholars. It presents humans in a “positive” light, but this is almost a kind of wishful thinking that is not supported by facts.

Humanistic psychology also rejects traditional science, but then what is supposed to replace it?

If humanistic psychology relies merely on “innermost feelings”, then it stops being psychology and instead becomes philosophy or perhaps even religion. Critics accuse humanistic psychology of taking the discipline back to its prescientific past (Hergenhahn)

Finally, many of the terms that humanistic psychologists use are quite vague. What exactly do we mean when we say things like “innermost feelings” or “actualizing our inherent potential”? These terms/phrases defy clear definition and verification, making them somewhat unreliable.

The humanistic theory of personality posits that all humans are driven to pursue their innermost feelings and reach their full potential.

This, however, is dependent on our surrounding environment. Most of us develop “conditions of worth”, which make us act in certain ways to be loved. Rogers’ attempt was to help people find (whether through personal relationships or therapy), “unconditional positive regard”.

This unconditional acceptance allows people to become fully functioning humans and reach their full potential. The humanistic theory of personality has been applied to various fields, such as education, client-centric therapy, etc.

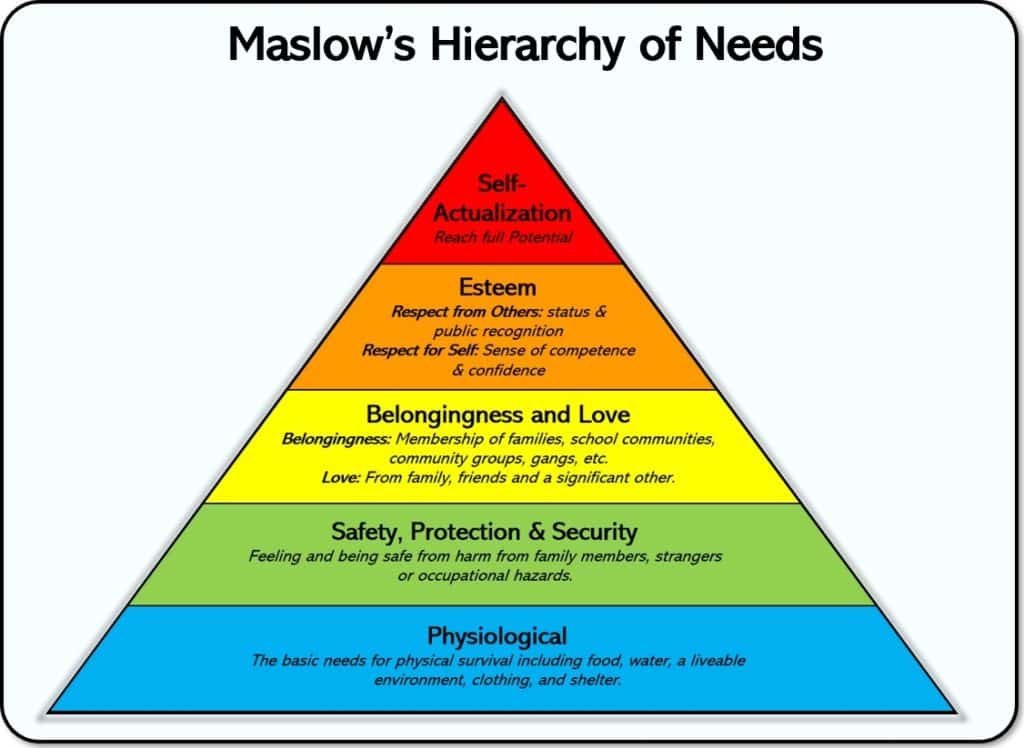

Read Next: Maslow’s Hierarchy

For students studying humanism, it’s worth taking a deep dive into Maslow’s hierarchy of needs here , which is without a doubt the most influential concept within the humanist theory of psychology. Below is a quick overview:

The states on Maslow’s hierarchy are:

- Physiological Needs – we first desire things that keep us alive, like air and water

- Safety and Security Needs – then, we desire things that make us feel safe and secure, like shelter and financial stability

- Love and Belonging (Social) Needs – then, we seek out social satisfaction through a sense of belonging to an in-group, a good family life, and finding friends or an intimate partner

- Esteem Needs – then, we seek respect from both our community and ourselves (self-esteem).

- Self-actualization – lastly, we seek self-actualization, by which Maslow means becoming the best version of ourselves. An example might be the deep satisfaction from raising happy children.

Hergenhahn, B. R. (2000). An Introduction to the History of Psychology. Wadsworth Publishing Co Inc.

Kinget, G. M. (1975). On being human: A systematic view . Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Rogers, Carl. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy . Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, Carl. (1954). Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications, and Theory . University of Chicago Press

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Indirect Democracy: Definition and Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Pluralism (Sociology): Definition and Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Equality Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Instrumental Learning: Definition and Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Carl Rogers Humanistic Theory and Contribution to Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Carl Rogers (1902-1987) was a humanistic psychologist best known for his views on the therapeutic relationship and his theories of personality and self-actualization.

Rogers (1959) believed that for a person to “grow”, they need an environment that provides them with genuineness (openness and self-disclosure ), acceptance (being seen with unconditional positive regard), and empathy (being listened to and understood).

Without these qualities, relationships and healthy personalities will not develop as they should, much like a tree will not grow without sunlight and water.

Rogers believed that every person could achieve their goals, wishes, and desires in life. When, or rather if they did so, self-actualization took place. This was one of Carl Rogers most important contributions to psychology, and for a person to reach their potential a number of factors must be satisfied.

Person-Centered Therapy

Rogers developed client-centered therapy (later re-named ‘person-centered’), a non-directive therapy, allowing clients to deal with what they considered important, at their own pace.

This method involves removing obstacles so the client can move forward, freeing him or her for normal growth and development. By using non-directive techniques, Rogers assisted people in taking responsibility for themselves.

He believed that the experience of being understood and valued gives us the freedom to grow, while pathology generally arises from attempting to earn others’ positive regard rather than following an ‘inner compass’.

Rogers recorded his therapeutic sessions, analyzed their transcripts, and examined factors related to the therapy outcome. He was the first person to record and publish complete cases of psychotherapy .

Rogers revolutionized the course of therapy. He took the, then, radical view that it might be more beneficial for the client to lead the therapy sessions rather than the therapist; as he says, ‘the client knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been buried’ (Rogers, 1961).

Personality Development

Central to Rogers’ personality theory is the notion of self or self-concept . This is “the organized, consistent set of perceptions and beliefs about oneself.”

Carl Rogers’ self-concept is a central theme in his humanistic theory of psychology. It encompasses an individual’s self-image (how they see themselves), self-esteem (how much value they place on themselves), and ideal self (the person they aspire to be).

The self is the humanistic term for who we really are as a person. The self is our inner personality, and can be likened to the soul, or Freud’s psyche . The self is influenced by the experiences a person has in their life, and out interpretations of those experiences.

Two primary sources that influence our self-concept are childhood experiences and evaluation by others.

According to Rogers (1959), we want to feel, experience, and behave in ways consistent with our self-image and which reflect what we would like to be like, our ideal self. The closer our self-image and ideal self are to each other, the more consistent or congruent we are and the higher our sense of self-worth.

Discrepancies between self-concept and reality can cause incongruence, leading to psychological tension and anxiety. A person is said to be in a state of incongruence if some of the totality of their experience is unacceptable to them and is denied or distorted in the self-image.

The humanistic approach states that the self is composed of concepts unique to ourselves. The self-concept includes three components:

Self-worth (or self-esteem ) is the value or worth an individual places on themselves. It’s the evaluative aspect of self-concept, influenced by the individual’s perceived successes, failures, and how they believe others view them.

High self-esteem indicates a positive self-view, while low self-esteem signifies self-doubt and criticism.

Rogers believed feelings of self-worth developed in early childhood and were formed from the interaction of the child with the mother and father.

Self-image refers to individuals’ mental representation of themselves, shaped by personal experiences and interactions with others.

It’s how people perceive their physical and personality traits, abilities, values, roles, and goals. It’s their understanding of “who I am.”

How we see ourselves, which is important to good psychological health. Self-image includes the influence of our body image on our inner personality.

At a simple level, we might perceive ourselves as a good or bad person, beautiful or ugly. Self-image affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves in the world.

Self-image vs. Real self

The self-image can sometimes be distorted or based on inaccurate perceptions . In contrast, the real self includes self-awareness of who a person truly is.

The real self represents a person’s genuine current state, including their strengths, weaknesses, and areas where they might struggle.

The ideal self is the version of oneself that an individual aspires to become.

It includes all the goals, values, and traits a person deems ideal or desirable. It’s their vision of “who I want to be.”

This is the person who we would like to be. It consists of our goals and ambitions in life, and is dynamic – i.e., forever changing. The ideal self in childhood is not the ideal self in our teens or late twenties.

According to Rogers, congruence between self-image and the ideal self signifies psychological health.

If the ideal self is unrealistic or there’s a significant disparity between the real and ideal self, it can lead to incongruence, resulting in dissatisfaction, unhappiness, and even mental health issues.

Therefore, as per Rogers, one of the goals of therapy is to help people bring their real self and ideal self into alignment, enhancing their self-esteem and overall life satisfaction.

Positive Regard and Self Worth

Carl Rogers (1951) viewed the child as having two basic needs: positive regard from other people and self-worth.

How we think about ourselves and our feelings of self-worth are of fundamental importance to psychological health and the likelihood that we can achieve goals and ambitions in life and self-actualization.

Self-worth may be seen as a continuum from very high to very low. To Carl Rogers (1959), a person with high self-worth, that is, has confidence and positive feelings about him or herself, faces challenges in life, accepts failure and unhappiness at times, and is open with people.

A person with low self-worth may avoid challenges in life, not accept that life can be painful and unhappy at times, and will be defensive and guarded with other people.

Rogers believed feelings of self-worth developed in early childhood and were formed from the interaction of the child with the mother and father. As a child grows older, interactions with significant others will affect feelings of self-worth.

Rogers believed that we need to be regarded positively by others; we need to feel valued, respected, treated with affection and loved. Positive regard is to do with how other people evaluate and judge us in social interaction. Rogers made a distinction between unconditional positive regard and conditional positive regard.

Unconditional Positive Regard

Unconditional positive regard is a concept in psychology introduced by Carl Rogers, a pioneer in client-centered therapy.

Unconditional positive regard is where parents, significant others (and the humanist therapist) accept and loves the person for what he or she is, and refrain from any judgment or criticism.

Positive regard is not withdrawn if the person does something wrong or makes a mistake.

Unconditional positive regard can be used by parents, teachers, mentors, and social workers in their relationships with children, to foster a positive sense of self-worth and lead to better outcomes in adulthood.

For example

In therapy, it can substitute for any lack of unconditional positive regard the client may have experienced in childhood, and promote a healthier self-worth.

The consequences of unconditional positive regard are that the person feels free to try things out and make mistakes, even though this may lead to getting it worse at times.

People who are able to self-actualize are more likely to have received unconditional positive regard from others, especially their parents, in childhood.

Examples of unconditional positive regard in counseling involve the counselor maintaining a non-judgmental stance even when the client displays behaviors that are morally wrong or harmful to their health or well-being.

The goal is not to validate or condone these behaviors, but to create a safe space for the client to express themselves and navigate toward healthier behavior patterns.

This complete acceptance and valuing of the client facilitates a positive and trusting relationship between the client and therapist, enabling the client to share openly and honestly.

Limitations

While simple to understand, practicing unconditional positive regard can be challenging, as it requires setting aside personal opinions, beliefs, and values.

It has been criticized as potentially inauthentic, as it might require therapists to suppress their own feelings and judgments.

Critics also argue that it may not allow for the challenging of unhelpful behaviors or attitudes, which can be useful in some therapeutic approaches.

Finally, some note a lack of empirical evidence supporting its effectiveness, though this is common for many humanistic psychological theories (Farber & Doolin, 2011).

Conditional Positive Regard

Conditional positive regard is a concept in psychology that refers to the expression of acceptance and approval by others (often parents or caregivers) only when an individual behaves in a certain acceptable or approved way.

In other words, this positive regard, love, or acceptance is conditionally based on the individual’s behaviors, attitudes, or views aligning with those expected or valued by the person giving the regard.

According to Rogers, conditional positive regard in childhood can lead to conditions of worth in adulthood, where a person’s self-esteem and self-worth may depend heavily on meeting certain standards or expectations.

These conditions of worth can create a discrepancy between a person’s real self and ideal self, possibly leading to incongruence and psychological distress.

Conditional positive regard is where positive regard, praise, and approval, depend upon the child, for example, behaving in ways that the parents think correct.

Hence the child is not loved for the person he or she is, but on condition that he or she behaves only in ways approved by the parent(s).

For example, if parents only show love and approval when a child gets good grades or behaves in ways they approve, the child may grow up believing they are only worthy of love and positive regard when they meet certain standards.

This may hinder the development of their true self and could contribute to struggles with self-esteem and self-acceptance.

At the extreme, a person who constantly seeks approval from other people is likely only to have experienced conditional positive regard as a child.

Congruence & Incongruence

A person’s ideal self may not be consistent with what actually happens in life and the experiences of the person. Hence, a difference may exist between a person’s ideal self and actual experience. This is called incongruence.

Where a person’s ideal self and actual experience are consistent or very similar, a state of congruence exists. Rarely, if ever, does a total state of congruence exist; all people experience a certain amount of incongruence.

The development of congruence is dependent on unconditional positive regard. Carl Rogers believed that for a person to achieve self-actualization, they must be in a state of congruence.

According to Rogers, we want to feel, experience, and behave in ways which are consistent with our self-image and which reflect what we would like to be like, our ideal-self.

The closer our self-image and ideal-self are to each other, the more consistent or congruent we are and the higher our sense of self-worth. A person is said to be in a state of incongruence if some of the totality of their experience is unacceptable to them and is denied or distorted in the self-image.

Incongruence is “a discrepancy between the actual experience of the organism and the self-picture of the individual insofar as it represents that experience.

As we prefer to see ourselves in ways that are consistent with our self-image, we may use defense mechanisms like denial or repression in order to feel less threatened by some of what we consider to be our undesirable feelings.

A person whose self-concept is incongruent with her or his real feelings and experiences will defend himself because the truth hurts.

Self Actualization

The organism has one basic tendency and striving – to actualize, maintain, and enhance the experiencing organism (Rogers, 1951, p. 487).

Rogers rejected the deterministic nature of both psychoanalysis and behaviorism and maintained that we behave as we do because of the way we perceive our situation. “As no one else can know how we perceive, we are the best experts on ourselves.”

Carl Rogers (1959) believed that humans have one basic motive, which is the tendency to self-actualize – i.e., to fulfill one’s potential and achieve the highest level of “human-beingness” we can.

According to Rogers, people could only self-actualize if they had a positive view of themselves (positive self-regard). This can only happen if they have unconditional positive regard from others – if they feel that they are valued and respected without reservation by those around them (especially their parents when they were children).

Self-actualization is only possible if there is congruence between the way an individual sees themselves and their ideal self (the way they want to be or think they should be). If there is a large gap between these two concepts, negative feelings of self-worth will arise that will make it impossible for self-actualization to take place.

The environment a person is exposed to and interacts with can either frustrate or assist this natural destiny. If it is oppressive, it will frustrate; if it is favorable, it will assist.

Like a flower that will grow to its full potential if the conditions are right, but which is constrained by its environment, so people will flourish and reach their potential if their environment is good enough.

However, unlike a flower, the potential of the individual human is unique, and we are meant to develop in different ways according to our personality. Rogers believed that people are inherently good and creative.

They become destructive only when a poor self-concept or external constraints override the valuing process. Carl Rogers believed that for a person to achieve self-actualization, they must be in a state of congruence.

This means that self-actualization occurs when a person’s “ideal self” (i.e., who they would like to be) is congruent with their actual behavior (self-image).

Rogers describes an individual who is actualizing as a fully functioning person. The main determinant of whether we will become self-actualized is childhood experience.

The Fully Functioning Person

Rogers believed that every person could achieve their goal. This means that the person is in touch with the here and now, his or her subjective experiences and feelings, continually growing and changing.

In many ways, Rogers regarded the fully functioning person as an ideal and one that people do not ultimately achieve.

It is wrong to think of this as an end or completion of life’s journey; rather it is a process of always becoming and changing.

Rogers identified five characteristics of the fully functioning person:

- Open to experience : both positive and negative emotions accepted. Negative feelings are not denied, but worked through (rather than resorting to ego defense mechanisms).

- Existential living : in touch with different experiences as they occur in life, avoiding prejudging and preconceptions. Being able to live and fully appreciate the present, not always looking back to the past or forward to the future (i.e., living for the moment).

- Trust feelings : feeling, instincts, and gut-reactions are paid attention to and trusted. People’s own decisions are the right ones, and we should trust ourselves to make the right choices.

- Creativity : creative thinking and risk-taking are features of a person’s life. A person does not play safe all the time. This involves the ability to adjust and change and seek new experiences.

- Fulfilled life : a person is happy and satisfied with life, and always looking for new challenges and experiences.

For Rogers, fully functioning people are well-adjusted, well-balanced, and interesting to know. Often such people are high achievers in society.

Critics claim that the fully functioning person is a product of Western culture. In other cultures, such as Eastern cultures, the achievement of the group is valued more highly than the achievement of any one person.

Carl Rogers Quotes

The very essence of the creative is its novelty, and hence we have no standard by which to judge it. (Rogers, 1961, p. 351)

I have gradually come to one negative conclusion about the good life. It seems to me that the good life is not any fixed state. It is not, in my estimation, a state of virtue, or contentment, or nirvana, or happiness. It is not a condition in which the individual is adjusted or fulfilled or actualized. To use psychological terms, it is not a state of drive-reduction , or tension-reduction, or homeostasis. (Rogers, 1967, p. 185-186)

The good life is a process, not a state of being. It is a direction not a destination. (Rogers, 1967, p. 187)

Unconditional positive regard involves as much feeling of acceptance for the client’s expression of negative, ‘bad’, painful, fearful, defensive, abnormal feelings as for his expression of ‘good’, positive, mature, confident, social feelings, as much acceptance of ways in which he is inconsistent as of ways in which he is consistent. It means caring for the client, but not in a possessive way or in such a way as simply to satisfy the therapist’s own needs. It means a caring for the client as a separate person, with permission to have his own feelings, his own experiences’ (Rogers, 1957, p. 225)

Frequently Asked Questions

How did carl rogers’ humanistic approach differ from other psychological theories of his time.

Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach differed from other psychological theories of his time by emphasizing the importance of the individual’s subjective experience and self-perception.

Unlike behaviorism , which focused on observable behaviors, and psychoanalysis , which emphasized the unconscious mind, Rogers believed in the innate potential for personal growth and self-actualization.

His approach emphasized empathy, unconditional positive regard, and genuineness in therapeutic relationships, aiming to create a supportive and non-judgmental environment where individuals could explore and develop their true selves.

Rogers’ humanistic approach placed the individual’s subjective experience at the forefront, prioritizing their unique perspective and personal agency.

What criticisms have been raised against Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach to psychology?

Critics of Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach to psychology argue that it lacks scientific rigor and empirical evidence compared to other established theories.

Some claim that its emphasis on subjective experiences and self-perception may lead to biased interpretations and unreliable findings. Additionally, critics argue that Rogers’ approach may overlook the influence of external factors, such as social and cultural contexts, on human behavior and development.

Critics also question the universal applicability of Rogers’ theories, suggesting that they may be more relevant to certain cultural or individual contexts than others.

How has Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach influenced other areas beyond psychology?

Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach has had a significant impact beyond psychology, influencing various areas such as counseling, education, leadership, and interpersonal relationships.

In counseling, his emphasis on empathy, unconditional positive regard, and active listening has shaped person-centered therapy and other therapeutic approaches. In education, Rogers’ ideas have influenced student-centered learning, fostering a more supportive and individualized approach to teaching.

His humanistic principles have also been applied in leadership development, promoting empathetic and empowering leadership styles.

Moreover, Rogers’ emphasis on authentic communication and understanding has influenced interpersonal relationships, promoting empathy, respect, and mutual growth.

What is the current relevance of Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach in modern psychology?

Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach maintains relevance in modern psychology by emphasizing the importance of individual agency, personal growth, and the therapeutic relationship.

It continues to inform person-centered therapy and other humanistic therapeutic modalities. Rogers’ focus on empathy, acceptance, and authenticity resonates with contemporary approaches that prioritize the client’s subjective experience and self-determination.

Additionally, his ideas on the role of positive regard and the creation of a safe, non-judgmental environment have implications for various domains, including counseling, education, and interpersonal relationships.

The humanistic approach serves as a reminder of the significance of the individual’s unique perspective and the power of empathetic connections in fostering well-being and growth.

- Bozarth, J. D. (1998). Person-centred therapy: A revolutionary paradigm . Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books

- Farber, B. A., & Doolin, E. M. (2011). Positive regard . Psychotherapy , 48 (1), 58.

- Mearns, D. (1999). Person-centred therapy with configurations of self. Counselling, 10(2), 125±130.

- Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory . London: Constable.

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change . Journal of consulting psychology , 21 (2), 95.

- Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In (ed.) S. Koch, Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the person and the social context . New York: McGraw Hill.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a person: A psychotherapists view of psychotherapy . Houghton Mifflin.

- Rogers, C. R., Stevens, B., Gendlin, E. T., Shlien, J. M., & Van Dusen, W. (1967). Person to person: The problem of being human: A new trend in psychology. Lafayette, CA: Real People Press.

- Wilkins, P. (1997). Congruence and countertransference: similarities and differences. Counselling, 8(1), 36±41.

- Wilkins, P. (2000). Unconditional positive regard reconsidered . British Journal of Guidance & Counselling , 28 (1), 23-36.

Case study: Musings on ‘John,’ his glasses, and existential-humanistic psychotherapy

“John” came to psychotherapy complaining of anxiety, dark moods, and difficulty connecting with others. A slight man, John wore glasses and made little eye contact with me in our our first meeting. When he did make eye contact though, I could not help but notice that he squinted, as if straining to see me.

He quickly detailed a laundry list of things in his life left undone for a number of vague reasons that, to me, were circular and hard to follow. He had not yet filed his divorce papers from a separation four years ago. He left a graduate program and owed the school money. He had been unemployed for several years and needed to find work. He wanted to smoke less marijuana. He needed to be more assertive with a friend, etc. From our first session, John struck me as an incredibly bright individual whose will had atrophied over the years.

Conventional (i.e., medical-model, treatment-focused) thinking in psychotherapy might say something like, “John is depressed, likely because of a chemical dysfunction in his brain. One of his primary symptoms is amotivation . Because he is depressed, he is unable to attend to the matters required of him (e.g., divorce papers, school loans).

While I do not wholly discount this reasoning, as a psychotherapist trained in existential-humanistic psychotherapy, I have a simultaneous, yet different perspective. Irvin Yalom suggested clients often present to psychotherapy feeling disappointed with the way they are living their lives. They experience existential guilt for making decisions that led to only partial fulfillment or complete denial of their potential. This guilt often manifests as depression, anxiety, or a combination of the two. With this in mind, we might say that John’s depression did not cause his lack of motivation, but his lack of motivation—his repeated decision to not act when an action was required—has led to his current depressed state.

Yalom also suggested that the work of psychotherapy is, in part, to re-engage the will of our clients so that they may live more fully within natural human limitations we all face. Additionally, existential-humanistic psychotherapy holds that the client will bring his or her way of being in the world into the consulting room. These ideas came to life when, several sessions into our work together, John began to make more eye contact (a good sign, I thought) and I commented on his squinting.

“Yes, yes,” he said. “It is a real problem. I got these bifocals two years ago and I’ve never been able to see with them.”

“You have gone two years with glasses that don’t help you see?” I asked, somewhat shocked.

“Yes,” he said. “And I think it really contributes to my mood. But there’s nothing I can do about it.”

“How’s that?”

“Well, I suppose I could do something about it,” he responded. “They just don’t fit right and never worked from the start.”

“How often have you thought about doing something about it?” I asked.

“I think about it all the time!” he said. “It drives me crazy, not being able to see.”

As this exchange continued, John attempted to move on to other topics several times. However, I found myself slightly obsessed with his glasses. It seemed like such an important symbol for his struggle to self-motivate. Having worn glasses myself, I found it hard to imagine how John could go so long not seeing clearly. Over and over, I brought us back to the glasses in the here-and-now, gently nudging him to deepen into what it was like for him to have this problem that drove him crazy but not to do anything about it. Although I immediately wanted to help him develop a plan to remedy the situation, I fought the impulse, opting instead to stay in John’s dilemma of inaction with him. I realized that to move too quickly would have been to impose my will on John, rather than waiting for John to come to his own willful action.

Now the reader might expect that I am going to finish this post by writing that John eventually bought new glasses and no longer strains to see me in my office. However, no such luck. What I can say is that John and I have discussed his glasses in subsequent sessions and, at his suggestion, have even discussed options (read choices) available to him to find new glasses. At the same time, in subtle ways, connections between his glasses and other domains of his life replete with unfinished business have been made. All of this feels like progress to me. However, conventional psychology, driven by behavioral outcomes, might argue otherwise. Perhaps it might argue that if I am going to use John’s glasses and his lack of motivation to get a new pair as any kind of indicator at all, then our work has not yet served him. After all, he still can’t see well.

As an existential-humanistic therapist, I guess I see it differently.

Humanistic Psychology’s Approach to Wellbeing: 3 Theories

That sounds quite nice, doesn’t it? Let’s repeat that again.

Humans are innately good.

Driving forces, such as morality, ethical values, and good intentions, influence behavior, while deviations from natural tendencies may result from adverse social or psychological experiences, according to the premise of humanistic psychology.

What does it mean to flourish as a human being? Why is it important to achieve self-actualization? And what is humanistic psychology, anyway?

Humanistic psychology has the power to provide individuals with self-actualization, dignity, and worth. Let’s see how that works in this article.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free . These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is the humanistic psychology approach, brief history of humanistic psychology, 10 real-life examples in therapy & education, popular humanistic theories of wellbeing, humanistic psychology and positive psychology, 4 techniques for humanistic therapists, 4 common criticisms of humanistic psychology, fascinating books on the topic, more resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Humanistic psychology is a holistic approach in psychology that focuses on the whole person. Humanists believe that a person is “in the process of becoming,” which places the conscious human experience as the nucleus of psychological establishment.

Humanistic psychology was developed to address the deficiencies of psychoanalysis , psychodynamic theory , and behaviorism . The foundation for this movement is understanding behavior by means of human experience.

This entity of psychology takes a phenomenological stance, where personality is studied from an individual’s subjective point of view.

Key focus of humanistic psychology

The tenets of humanistic psychology, which are also shared at their most basic level with transpersonal and existential psychology, include:

- Humans cannot be viewed as the sum of their parts or reduced to functions/parts.

- Humans exist in a unique human context and cosmic ecology.

- Human beings are conscious and are aware of their awareness.

- Humans have a responsibility because of their ability to choose.

- Humans search for meaning, value, and creativity besides aiming for goals and being intentional in causing future events (Aanstoos et al., 2000).

In sum, the focus of humanistic psychology is on the person and their search for self-actualization .

At this time, humanistic psychology was considered the third force in academic psychology and viewed as the guide for the human potential movement (Taylor, 1999).

The separation of humanistic psychology as its own category was known as Division 32. Division 32 was led by Amedeo Giorgi, who “criticized experimental psychology’s reductionism, and argued for a phenomenologically based methodology that could support a more authentically human science of psychology” (Aanstoos et al., 2000, p. 6).

The Humanistic Psychology Division (32) of the American Psychological Association was founded in September 1971 (Khan & Jahan, 2012). Humanistic psychology had not fully emerged until after the radical behaviorism era; however, we can trace its roots back to the philosophies of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger.

Husserl spurred the phenomenological movement and suggested that theoretical assumptions be set aside, and philosophers and scientists should instead describe immediate experiences of phenomena (Schneider et al., 2015).

Who founded humanistic psychology?

The first phase of humanistic psychology, which covered the period between 1960 to 1980, was largely driven by Maslow’s agenda for positive psychology . It articulated a view of the human being as irreducible to parts, needing connection, meaning, and creativity (Khan & Jahan, 2012).

The original theorists of humanistic theories included Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May, who postulated that behaviorism and psychoanalysis were inadequate in explaining human nature (Schneider et al., 2015).

Prior to these researchers, Allport, Murray, and Murphy had protested the reductionist movement, including the white laboratory rat as a method for comparing human behavior (Schneider et al., 2015). Influential women in the development of this branch of psychology included Frieden and Criswell (Serlin & Criswell, 2014).

Carl Rogers’s work

Carl Rogers developed the concept of client-centered therapy , which has been widely used for over 40 years (Carter, 2013). This type of therapy encourages the patient toward self-actualization through acceptance and empathetic listening by the therapist. This perspective asserts that a person is fully developed if their self is aligned with their organism (Robbins, 2008).

In other words, a fully functioning person is someone who is self-actualized. This concept is important, as it presents the need for therapy as a total experience.

Rogers’s contribution assisted the effectiveness of person-centered therapy through his facilitation of clients reaching self-actualization and fully functional living. In doing so, Rogers focused on presence, congruence, and acceptance by the therapist (Aanstoos et al., 2000).

The Humanistic Theory by Carl Rogers – Mister Simplify

The human mind is not just reactive; it is reflective, creative, generative, and proactive (Bandura, 2001). With this being said, humanistic psychology has made major impacts in therapeutic and educational settings.

Humanistic psychology in therapy

The humanistic, holistic perspective on psychological development and self-actualization provides the foundation for individual and family counseling (Khan & Jahan, 2012). Humanistic therapies are beneficial because they are longer, place more focus on the client, and focus on the present (Waterman, 2013).

Maslow and Rogers were at the forefront of delivering client-centered therapy as they differentiated between self-concept as understanding oneself, society’s perception of themselves, and actual self. This humanistic psychological approach provides another method for psychological healing and is viewed as a more positive form of psychology. Rogers “emphasized the personality’s innate drive toward achieving its full potential” (McDonald & Wearing, 2013, p. 42–43).

Other types of humanistic-based therapies include:

- Logotherapy is a therapeutic approach aimed at helping individuals find the meaning of life. This technique was created by Victor Frankl, who posited that to live a meaningful life, humans need a reason to live (Melton & Schulenberg, 2008).

- Gestalt Therapy’s primary aim is to restore the wholeness of the experience of the person, which may include bodily feelings, movements, emotions, and the ability to creatively adjust to environmental conditions. This type of therapy is tasked with providing the client with awareness and awareness tools (Yontef & Jacobs, 2005). This includes the use of re-enactments and role-play by empowering awareness in the present moment.

- Existential Therapy aims to aid clients in accepting and overcoming the existential fears inherent in being human. Clients are guided in learning to take responsibility for their own choices. Rather than explaining the human predicament, existential therapy techniques involve exploring and describing the conflict.

- Narrative Therapy is goal directed, with change being achieved by exploring how language is used to construct and maintain problems. The method involves the client’s narrative interpretation of their experience in the world (Etchison & Kleist, 2000).

Humanistic psychology has developed a variety of research methodologies and practice models focused on facilitating the development and transformation of individuals, groups, and organizations (Resnick et al., 2001).

The methodologies include narrative, imaginal, and somatic approaches. The practices range from personal coaching and organizational consulting through creative art therapies to philosophy (Resnick et al., 2001).

Humanistic approach in education

The thoughts of Dewey and Bruner regarding the humanistic movement and education greatly affect education today. Dewey proclaimed that schools should influence social outcomes by teaching life skills in a meaningful way (Starcher & Allen, 2016).

Bruner was an enthusiast of constructivist learning and believed in making learners autonomous by using methods such as scaffolding and discovery learning (Starcher & Allen, 2016).

Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (Resnick et al., 2001) asserts that there are eight different types of intelligence: linguistic, logical/mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalist. In education, it is important for educators to address as many of these areas as possible.

These psychologists soon set the tone for a more intense focus on humanistic skills, such as self-awareness, communication, leadership ability, and professionalism. Humanistic psychology impacts the educational system with its perspectives on self-esteem and self-help (Khan & Jahan, 2012; Resnick et al., 2001).

Maslow extended this outlook with his character learning (Starcher & Allen, 2016). Character learning is a means for obtaining good habits and creating a moral compass. Teaching young children morality is paramount in life (Birhan et al., 2021).

In concentrating on these aspects, the focus is placed on the future, self-improvement, and positive change. Humanistic psychology rightfully provides individuals with self-actualization, dignity, and worth.

Silvan Tomkins theorized the script theory, which led to the advancement of personality psychology and opened the door to many narrative-based theories involving myths, plots, episodes, character, voices, dialogue, and life stories (McAdams, 2001).

Tomkins’s affect theory followed this theory and explains human behavior as falling into scripts or patterns. It appears as though this theory’s acceptance led to many more elements of experience being considered (McAdams, 2001).

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs has contributed much to humanistic psychology and impacts mental and physical health . This pyramid is frequently used within the educational system, specifically for classroom management purposes. In the 1960s and 1970s, this model was expanded to include cognitive, aesthetic, and transcendence needs (McLeod, 2017).

Maslow’s focus on what goes right with people as opposed to what goes wrong with them and his positive accounts of human behavior benefit all areas of psychology.

Download 3 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find meaning in life help and pursue directions that are in alignment with values.

Download 3 Free Meaning Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Although humanistic psychology and positive psychology share the basic ideas of psychological wellbeing – the intent to achieve individual human potential and a humanistic framework – their origins are quite different (Medlock, 2012). Humanistic psychology adds two important elements to the establishment of positive psychology: epistemology and its audience (Taylor, 2001).

Humanistic psychology and positive psychology share many overlapping thematic contents and theoretical presuppositions (Robbins, 2008).

Much of the work in positive psychology was developed from the work in humanistic psychology (Medlock, 2012). Positive psychology was also first conceived by Maslow in 1954 and then further discussed in an article by Martin Seligman (Shourie & Kaur, 2016).

Seligman’s purpose for positive psychology was to focus on the characteristics that make life worth living as opposed to only studying the negatives, such as mental illness (Shrestha, 2016).

Congruence refers to both the intra- and interpersonal characteristics of the therapist (Kolden et al., 2011).

This requires the therapist to bring a mindful genuineness and conscientiously share their experience with the client.

Active listening

Active listening helps to foster a supportive environment. For example, response tokens such as “uh-huh” and “mm-hmm” are effective ways to prompt the client to continue their dialogue (Fitzgerald & Leudar, 2010).

Looking at the client, nodding occasionally, using facial expressions, being aware of posture, paraphrasing, and asking questions are also ways to maintain active listening.

Reflective understanding

Similar to active listening, reflective understanding includes restating and clarifying what the client is saying. This technique is important, as it draws the client’s awareness to their emotions, allowing them to label. Employing Socratic questioning would ensure a reflective understanding in your practice (Bennett-Levy et al., 2009).

Unconditional positive regard

Unconditional positive regard considers the therapist’s attitude toward the patient. The therapist’s enduring warmth and consistent acceptance shows their value for humanity and, more specifically, their client.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Some may assert that humanistic psychology is not exclusively defined by the senses or intellect (Taylor, 2001).

Humanistic psychology was also once thought of as a touchy-feely type of psychology. Instead, internal dimensions such as self-knowledge, intuition, insight, interpreting one’s dreams, and the use of guided mental imagery are considered narcissistic by critics of humanistic psychology (Robbins, 2008; Taylor, 2001).

Further, studying internal conditions, such as motives or traits, was frowned upon at one time (Polkinghorne, 1992).

Aanstoos et al. (2000) note Skinner’s thoughts concerning humanistic psychology as being the number one barrier in psychology’s stray from a purely behavioral science. Religious fundamentalists were also opposed to this new division and referred to people of humanistic psychology as secular humanists.

Humanistic psychology is sometimes difficult to assess and has even been charged as being poor empirical science (DeRobertis, 2021). That is because of the uncommon belief that the outcome should be driven more by the participants rather than the researchers (DeRobertis & Bland, 2021).

If you find this topic intriguing and want to find out even more, then take a look at the following books.

1. Becoming an Existential-Humanistic Therapist: Narratives From the Journey – Julia Falk and Louis Hoffman

If you’re interested in becoming an existential-humanistic psychologist or counselor, you may want to refer to this collection of therapists and counselors who have already made this journey.

Perhaps you are a student who is considering pursuing this direction in psychology.

Regardless, this book contains reflective exercises for individuals considering pursuing a career as an existential-humanistic counselor or therapist, as well as exercises for current therapists to reflect on their own journey.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy – Carl Rogers

If your intent is to explore client-centered therapy more in depth, you may want to pick up this book by one of humanistic psychology’s founders.

In this text, Rogers sheds light on this important therapeutic encounter and human potential.

3. Man’s Search for Meaning – Viktor Frankl

Also by one of humanistic psychology’s founders, Man’s Search for Meaning provides an explanation of Logotherapy.

With his actual horrific experiences in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl declares that humans’ primary drive in life is not pleasure, but the discovery and pursuit of what they personally find meaningful.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of humanistic psychology, our article The Five Founding Fathers and a History of Positive Psychology would be an excellent reference, as the roots of humanistic and positive psychology are entangled.

In humanistic psychology, self-awareness and introspection are important. Try using our Self-Awareness Worksheet for Adults to learn more about yourself and increase your self-knowledge.

Journaling is an effective way to boost your internal self-awareness. Try using this Gratitude Journal and Who Am I? worksheet as starting points.

Perhaps you would benefit from our science and research-driven 17 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises . Use them to help others choose directions for their lives in alignment with what is truly important to them.

17 Tools To Encourage Meaningful, Value-Aligned Living

This 17 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises [PDF] pack contains our best exercises for helping others discover their purpose and live more fulfilling, value-aligned lives.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Humanistic psychology is a total package because it encompasses legends of the field, empirical research, strong philosophical foundations, and arts and literature connections (Bargdill, 2011).

Some may refute this statement, but prior to humanistic psychology, there was not an effective method for truly understanding humanistic issues without deviating from traditional psychological science (Kriz & Langle, 2012).

Humanistic psychology offers a different approach that can be used to positively impact your therapeutic practice or enhance your classroom practice. We hope you find these theories and techniques helpful in facilitating self-actualization, dignity, and worth in your clients and students.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free .

- Aanstoos, C. M., Serlin, I., & Greening, T. (2000). A history of division 32: Humanistic psychology. In D. A. Dewsbury (Ed.). History of the divisions of APA (pp. 85–112). APA Books.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology , 52 , 1–26.

- Bargdill, R. (2011). The youth movement in humanistic psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 39 (3), 283–287.

- Bennett-Levy, J., Thwaites, R., Chaddock, A., & Davis, M. (2009). Reflective practice in cognitive behavioural therapy: the engine of lifelong learning. In R. Dallos & J. Stedmon (Eds.), Reflective practice in psychotherapy and counselling (pp. 115–135). Open University Press.

- Birhan, W., Shiferaw, G., Amsalu, A., Tamiru, M., & Tiruye, H. (2021). Exploring the context of teaching character education to children in preprimary and primary schools. Social Sciences & Humanities Open , 4 (1), 100171.

- Carter, S. (2013). Humanism . Research Starters: Education.

- Corbett, L., & Milton, M. (2011). Existential therapy: A useful approach to trauma? Counselling Psychology Review , 26 (1), 62–74.

- DeRobertis, E. M. (2021). Epistemological foundations of humanistic psychology’s approach to the empirical. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology . Advance online publication.

- DeRobertis, E. M., & Bland, A. M. (2021). Humanistic and positive psychologies: The continuing narrative after two decades. Journal of Humanistic Psychology .

- Etchison, M., & Kleist, D. M. (2000). Review of narrative therapy: Research and utility. The Family Journal , 8 (1), 61–66.

- Falk, J., & Hoffman, L. (2022). Becoming an existential-humanistic therapist: Narratives from the journey. University Professors Press.

- Fitzgerald, P., & Leudar, I. (2010). On active listening in person-centred, solution-focused psychotherapy. Journal of Pragmatics , 42 (12), 3188–3198.

- Frankl, V. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

- Khan, S., & Jahan, M. (2012). Humanistic psychology: A rise for positive psychology. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology , 3 (2), 207–211.

- Kolden, G. G., Klein, M. H., Wang, C. C., & Austin, S. B. (2011). Congruence/genuineness. Psychotherapy , 48 (1), 65–71.

- Kriz, J., & Langle, A. (2012). A European perspective on the position papers. Psychotherapy , 49 (4), 475–479.

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology , 5 (2), 100–122.

- McDonald, M., & Wearing, S. (2013). A reconceptualization of the self in humanistic psychology: Heidegger, Foucault and the sociocultural turn. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology , 44 (1), 37–59.

- McLeod, S. A. (2017). Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs . SimplyPsychology. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

- Medlock, G. (2012). The evolving ethic of authenticity: From humanistic to positive psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 40 (1), 38–57.

- Melton, A. M., & Schulenberg, S. E. (2008). On the measurement of meaning: Logotherapy’s empirical contributions to humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist , 36 (1), 31–44.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1992). Research methodology in humanistic psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 20 (2–3), 218–242.

- Resnick, S., Warmoth, A., & Serlin, I. A. (2001). The humanistic psychology and positive psychology connection: Implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 41 (1), 73–101.

- Robbins, B. D. (2008). What is the good life? Positive psychology and the renaissance of humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist , 36 (2), 96–112.

- Rogers, C. (1995). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. HarperOne.

- Schneider, K. J., Pierson, J. F., & Bugental, J. F. T. (Eds.). (2015). The handbook of humanistic psychology: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Serlin, I. A., & Criswell, E. (2014). Humanistic psychology and women. In K. J. Schneider, J. F. Pierson, & J. F. T. Bugental (Eds.), The handbook of humanistic psychology: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 27–40). SAGE.

- Shourie, S., & Kaur, H. (2016). Gratitude and forgiveness as correlates of well-being among adolescents. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing , 7 (8), 827–833.

- Shrestha, A. K. (2016). Positive psychology: Evolution, philosophical foundations, and present growth. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology , 7 (4), 460–465.

- Starcher, D., & Allen, S. L. (2016). A global human potential movement and a rebirth of humanistic psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 44 (3), 227–241.

- Taylor, E. (1999). An intellectual renaissance of humanistic psychology? Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 39 (2), 7–25.

- Taylor, E. (2001). Positive psychology and humanistic psychology: A reply to Seligman. Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 41 (1), 13–29.

- Waterman, A. S. (2013). The humanistic psychology–positive psychology divide: Contrasts in philosophical foundations. American Psychologist , 68 (3), 124–133.

- Yontef, G., & Jacobs, L. (2005). Gestalt therapy. In R. J. Corsini & D. Wedding (Eds.), Current psychotherapies (pp. 299–336).

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Hierarchy of Needs: A 2024 Take on Maslow’s Findings

One of the most influential theories in human psychology that addresses our quest for wellbeing is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. While Maslow’s theory of [...]

Emotional Development in Childhood: 3 Theories Explained

We have all witnessed a sweet smile from a baby. That cute little gummy grin that makes us smile in return. Are babies born with [...]

Using Classical Conditioning for Treating Phobias & Disorders

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell? Classical conditioning, a psychological phenomenon first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the late 19th century, has proven to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (22)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (37)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies for Substance Abuse. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 1999. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 34.)

Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies for Substance Abuse.

- Order print copy from SAMHSA

Chapter 6 --Brief Humanistic and Existential Therapies

Humanistic and existential psychotherapies use a wide range of approaches to case conceptualization, therapeutic goals, intervention strategies, and research methodologies. They are united by an emphasis on understanding human experience and a focus on the client rather than the symptom. Psychological problems (including substance abuse disorders) are viewed as the result of inhibited ability to make authentic, meaningful, and self-directed choices about how to live. Consequently, interventions are aimed at increasing client self-awareness and self-understanding.

Whereas the key words for humanistic therapy are acceptance and growth , the major themes of existential therapy are client responsibility and freedom . This chapter broadly defines some of the major concepts of these two therapeutic approaches and describes how they can be applied to brief therapy in the treatment of substance abuse disorders. A short case illustrates how each theory would approach the client's issues. Many of the characteristics of these therapies have been incorporated into other therapeutic approaches such as narrative therapy.

Humanistic and existential approaches share a belief that people have the capacity for self-awareness and choice. However, the two schools come to this belief through different theories. The humanistic perspective views human nature as basically good, with an inherent potential to maintain healthy, meaningful relationships and to make choices that are in the interest of oneself and others. The humanistic therapist focuses on helping people free themselves from disabling assumptions and attitudes so they can live fuller lives. The therapist emphasizes growth and self-actualization rather than curing diseases or alleviating disorders. This perspective targets present conscious processes rather than unconscious processes and past causes, but like the existential approach, it holds that people have an inherent capacity for responsible self-direction. For the humanistic therapist, not being one's true self is the source of problems. The therapeutic relationship serves as a vehicle or context in which the process of psychological growth is fostered. The humanistic therapist tries to create a therapeutic relationship that is warm and accepting and that trusts that the client's inner drive is to actualize in a healthy direction.

The existentialist, on the other hand, is more interested in helping the client find philosophical meaning in the face of anxiety by choosing to think and act authentically and responsibly. According to existential therapy, the central problems people face are embedded in anxiety over loneliness, isolation, despair, and, ultimately, death. Creativity, love, authenticity, and free will are recognized as potential avenues toward transformation, enabling people to live meaningful lives in the face of uncertainty and suffering. Everyone suffers losses (e.g., friends die, relationships end), and these losses cause anxiety because they are reminders of human limitations and inevitable death. The existential therapist recognizes that human influence is shaped by biology, culture, and luck. Existential therapy assumes the belief that people's problems come from not exercising choice and judgment enough--or well enough--to forge meaning in their lives, and that each individual is responsible for making meaning out of life. Outside forces, however, may contribute to the individual's limited ability to exercise choice and live a meaningful life. For the existential therapist, life is much more of a confrontation with negative internal forces than it is for the humanistic therapist.

In general, brief therapy demands the rapid formation of a therapeutic alliance compared with long-term treatment modalities. These therapies address factors shaping substance abuse disorders, such as lack of meaning in one's life, fear of death or failure, alienation from others, and spiritual emptiness. Humanistic and existential therapies penetrate at a deeper level to issues related to substance abuse disorders, often serving as a catalyst for seeking alternatives to substances to fill the void the client is experiencing. The counselor's empathy and acceptance, as well as the insight gained by the client, contribute to the client's recovery by providing opportunities for her to make new existential choices, beginning with an informed decision to use or abstain from substances. These therapies can add for the client a dimension of self-respect, self-motivation, and self-growth that will better facilitate his treatment. Humanistic and existential therapeutic approaches may be particularly appropriate for short-term substance abuse treatment because they tend to facilitate therapeutic rapport, increase self-awareness, focus on potential inner resources, and establish the client as the person responsible for recovery. Thus, clients may be more likely to see beyond the limitations of short-term treatment and envision recovery as a lifelong process of working to reach their full potential.

Because these approaches attempt to address the underlying factors of substance abuse disorders, they may not always directly confront substance abuse itself. Given that the substance abuse is the primary presenting problem and should remain in the foreground, these therapies are most effectively used in conjunction with more traditional treatments for substance abuse disorders. However, many of the underlying principles that have been developed to support these therapies can be applied to almost any other kind of therapy to facilitate the client-therapist relationship.

- Using Humanistic and Existential Therapies

Many aspects of humanistic and existential approaches (including empathy, encouragement of affect, reflective listening, and acceptance of the client's subjective experience) are useful in any type of brief therapy session, whether it involves psychodynamic, strategic, or cognitive-behavioral therapy. They help establish rapport and provide grounds for meaningful engagement with all aspects of the treatment process.

While the approaches discussed in this chapter encompass a wide variety of therapeutic interventions, they are united by an emphasis on lived experience, authentic (therapeutic) relationships, and recognition of the subjective nature of human experience. There is a focus on helping the client to understand the ways in which reality is influenced by past experience, present perceptions, and expectations for the future. Schor describes the process through which our experiences assume meaning as apperception ( Schor, 1998 ). Becoming aware of this process yields insight and facilitates the ability to choose new ways of being and acting.

For many clients, momentary circumstances and problems surrounding substance abuse may seem more pressing, and notions of integration, spirituality, and existential growth may be too remote from their immediate experience to be effective. In such instances, humanistic and existential approaches can help clients focus on the fact that they do, indeed, make decisions about substance abuse and are responsible for their own recovery.

Essential Skills

By their very nature, these models do not rely on a comprehensive set of techniques or procedures. Rather, the personal philosophy of the therapist must be congruent with the theoretical underpinnings associated with these approaches. The therapist must be willing and able to engage the client in a genuine and authentic fashion in order to help the client make meaningful change. Sensitivity to "teachable" or "therapeutic" moments is essential.

When To Use Brief Humanistic and Existential Therapies