- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 25 November 2008

A case of PTSD presenting with psychotic symptomatology: a case report

- Georgios D Floros 1 ,

- Ioanna Charatsidou 1 &

- Grigorios Lavrentiadis 1

Cases Journal volume 1 , Article number: 352 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

A male patient aged 43 presented with psychotic symptomatology after a traumatic event involving accidental mutilation of the fingers. Initial presentation was uncommon although the patient responded well to pharmacotherapy. The theoretical framework, management plan and details of the treatment are presented.

Recent studies have shown that psychotic symptoms can be a hallmark of post-traumatic stress disorder [ 1 , 2 ]. The vast majority of the cases reported concerned war veterans although there were sporadic incidents involving non-combat related trauma (somatic or psychic). There is a biological theoretical framework for the disease [ 3 ] as well as several psychological theories attempting to explain cognitive aspects [ 4 ].

Case presentation

A male patient, aged 43, presented for treatment with complaints tracing back a year ago to a traumatic work-related event involving mutilation of the distal phalanges of his right-hand fingers. Main complaints included mixed hallucinations, irritability, inability to perform everyday tasks and depressive mood. No psychic symptomatology was evident before the event to him or his social milieu.

Mental state examination

The patient was a well-groomed male of short stature, sturdy build and average weight. He was restless but not agitated, with a guarded attitude towards the interviewer. His speech pattern was slow and sparse, his voice low. He described his current mood as 'anxious' without being able to provide with a reason. Patient appeared dysphoric and with blunted affect. He was able to maintain a linear train of thought with no apparent disorganization or irrational connections when expressing himself. Thought content centred on his amputated fingers with a semi-compulsive tendency to gaze to his (gloved) hand. The patient was typically lost in ruminations about his accident with a focus on the precise moment which he experienced as intrusive and affectively charged in a negative and painful way. He could remember wishing for his fingers to re-attach to his hand almost as the accident took place. A trigger in his intrusive thoughts was the painful sensation of neuropathic pain from his half-mutilated fingers, an artefact of surgery.

He denied and thoughts of harming himself and demonstrated no signs of aggression towards others. Hallucinations had a predominantly depressive and ego-dystonic character. He denied any perceptual disturbances at the time of the examination. Their appearance was typically during nighttime especially in the twilight. Initially they were visual only, involving shapes and rocks tumbling down towards the patient, gradually becoming more complex and laden with significance. A mixed visual and tactile hallucination of burning rain came afterwards while in the time of examination a tall stranger clad in black and raiding a tall steed would threaten and ridicule the patient. He scored 21 on a MMSE with trouble in the attention, calculation and recall categories. The patient appeared reliable and candid to the extent of his self-disclosure, gradually opening up to the interviewer but displayed a marked difficulty on describing his emotions and memories of the accident, apparently independent of his conscious will. His judgement was adequate and he had some limited Insight into his difficulties, hesitantly attributing them to his accident.

He was married and a father of three (two boys and a girl aged 7–12) He had no prior medical history for mental or somatic problems and received no medication. He admitted to occasional alcohol consumption although his relatives confirmed that he did not present addiction symptoms. He had some trouble making ends meet for the past five years. Due to rampant unemployment in his hometown, he was periodically employed in various jobs, mostly in the construction sector. One of his children has a congenital deformity, underwent several surgical procedures with mixed results and, before the time of the patient's accident, it was likely that more surgery would be forthcoming. The patient's father was a proud man who worked hard but reportedly was victimized by his brothers, they reaping the benefits of his work in the fields by manipulating his own father. He suffered a nervous breakdown attributed to his low economic status after a failed economic endeavour ending in him being robbed of the profits, seven years before the accident. There was no other relevant family history.

Before the accident the patient was a lively man, heavily involved as a participant and organizer in important local social events from a young age. He was respected by his fellow villagers and felt his involvement as a unique source of pride in an otherwise average existence. Prior to his accident, the patient was repeatedly promised a permanent job as a labourer and fate would have it that his appointment was supposedly approved immediately after the accident only to be subsequently revoked. He viewed himself as an exploited man in his previous jobs, much the same way his father was, while he harboured an extreme bitterness over the unavailability of support for his long-standing problems. His financial status was poor, being in sick-leave from his previous job for the last four months following the accident and hoping to receive some compensation. Although his injuries were considered insufficient for disability pension he could not work to his full capacity since the hand affected was his primary one and he was a manual labourer.

Given that the patient clearly suffered a high level of distress as a result of his hallucinatory experiences he was voluntary admitted to the 2nd Psychiatric Department of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki for further assessment, observation and treatment. A routine blood workup was ordered with no abnormalities. A Rorschach Inkblot Test was administered in order to gain some insight into patient's dynamics, interpersonal relations and underlying personality characteristics while ruling out any malingering or factitious components in the presentation as suggested in Wilson and Keane [ 5 ]. Results pointed to inadequate reality testing with slight disturbances in perception and a difficulty in separating reality from fantasy, leading to mistaken impressions and a tendency to act without forethought in the face of stress. Uncertainty in particular was unbearable and adjustment to a novel environment hard. Cognitive functions (concentration, attention, information processing, executive functions) were impaired possibly due to cognitive inability or neurological disease. Emotion was controlled with a tendency for impulsive behaviour; however there was difficulty in processing and expressing emotions in an adaptive manner. There were distinct patterns of aggression and anger towards others but expressing those patterns was avoided, switching to passivity and denial rather than succumbing to destructive urges or mature competitiveness. Self-esteem was low with feelings of inferiority and inefficiency.

A neurological examination revealed a left VI cranial nerve paresis, reportedly congenital, resulting in diplopia while gazing to the extreme left, which did not significantly affect the patient. The patient had a chronic complaint of occasional vertigo, to which he partly attributed his accident, although the symptoms were not of a persisting nature.

Initial diagnosis at this stage was 'Psychotic disorder NOS' and pharmacological treatment was initiated. An MRI scan of the brain with gadolinium contrast was ordered to rule out any focal neurological lesions. It was performed fifteen days later and revealed no abnormalities.

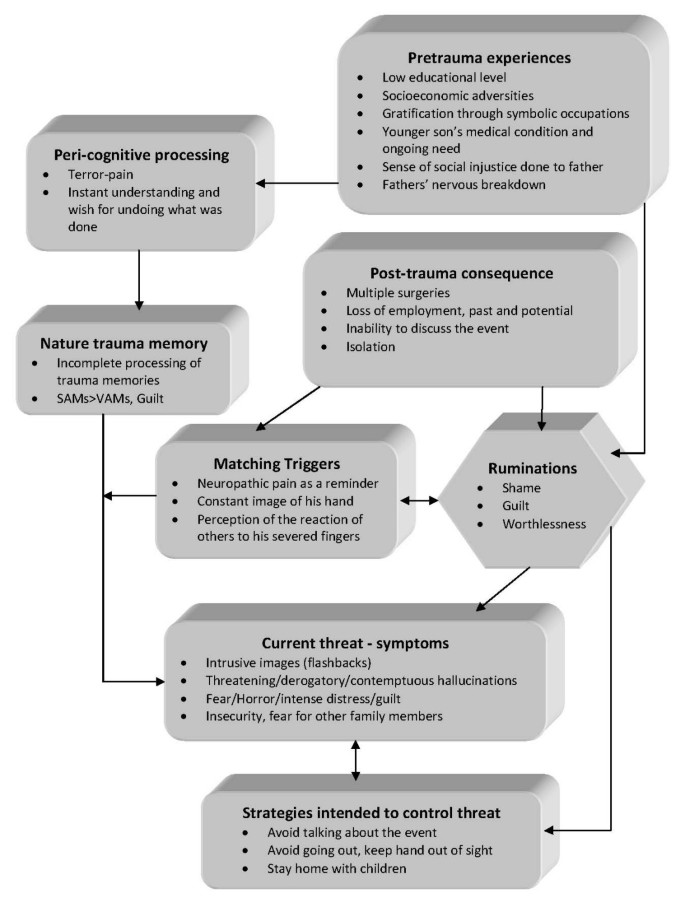

Patient was placed on ziprasidone 40 mg bid and lorazepam 1 mg bid. He reported an immediate improvement but when the attending physician enquired as to the nature of the improvement the patient replied that in his hallucinations he told the tall raider that he now had a tall doctor who would help him and the raider promptly left (sic). Apparently, the random assignment of a strikingly tall physician had an unexpected positive effect. Ziprasidone gradually increased to 80 mg bid within three days with no notable effect to the perceptual disturbances but with the development of akathisia for which biperiden was added, 1 mg tid. Duloxetine was added, 60 mg once-daily, in a hope that it could have a positive effect to his mood but also to this neuropathic pain which was frequent and demoralising. The patient had a tough time accommodating to the hospital milieu, although the grounds were extended and there was plenty of opportunity for walks and other activities. He preferred to stay in bed sometimes in obvious agony and with marked insomnia. He presented a strong fear for the welfare of his children, which he could not reason for. Due to the apparent inability of ziprasidone to make a dent in the psychotic symptomatology, medication was switched to amisulpride 400 mg bid and the patient was given a leave for the weekend to visit his home. On his return an improvement in his symptoms was reported by him and close relatives, although he still had excessive anxiety in the hospital setting. It was decided that his leave was to be extended and the patient would return for evaluation every third day. After three appointments he had a marked improvement, denied any psychotic symptoms while his sleep pattern improved. A good working relationship was established with his physician and the patient was with a schedule of follow-up appointments initially every fifteen days and following two months, every thirty days. His exit diagnosis was "Psychotic disorder Not Otherwise Specified – PTSD". He remained asymptomatic for five months and started making in-roads in a cognitively-oriented psychotherapeutic approach but unfortunately further trouble befell him, his wife losing a baby and his claim to an injury compensation rejected. He experienced a mood loss and duloxetine was increased to 120 mg per day to some positive effect. His status remains tenuous but he retains a strong will to make his appointments and work with his physician. A case conceptualization following a cognitive framework [ 6 ] is presented in Figure 1 .

Case formulation – (Persistent PTSD, adapted from Ehlers and Clark [ 6 ] ) . Case formulation following the persistent PTSD model of Ehlers and Clark [ 6 ]. It is suggested that the patient is processing the traumatic information in a way which a sense of immediate threat is perpetuated through negative appraisals of trauma or its consequences and through the nature of the traumatic experience itself. Peri-traumatic influences that operate at encoding, affect the nature of the trauma memory. The memory of the event is poorly elaborated, not given a complete context in time and place, and inadequately integrated into the general database of autobiographical knowledge. Triggers and ruminations serve to re-enact the traumatic information while symptoms and maladaptive coping strategies form a vicious circle. Memories are encoded in the SAM rather than the VAM system, thus preventing cognitive re-appraisal and eventual overcoming of traumatic experience [ 4 ].

The value of a specialized formulation is made clear in complex cases as this one. There is a relationship between the pre-existing cognitive schemas of the individual, thought patterns emerging after the traumatic event and biological triggers. This relationship, best described as a maladaptive cognitive processing style, culminates into feelings of shame, guilt and worthlessness which are unrelated to similar feelings, which emerge during trauma recollection, but nonetheless acts in a positive feedback loop to enhance symptom severity and keep the subject in a constant state of psychotic turmoil. Its central role is addressed in our case formulation under the heading "ruminations" which best describes its ongoing and unrelenting character. The "what if" character of those ruminations may serve as an escape through fantasy from an unbearably stressful cognition. Past experience is relived as current threat and the maladaptive coping strategies serve as negative re-enforcers, perpetuating the emotional suffering.

The psychosocial element in this case report, the patient's involvement with a highly symbolic activity, demonstrates the importance of individualising the case formulation. Apparently the patient had a chronic difficulty in expressing his emotions and integrating into his social surroundings, a difficulty counter-balanced somewhat with his involvement in the local social events which gave him not only a creative way out from any emotional impasse but also status and recognition. His perceived inability to continue with his symbolic activities was not only an indicator of the severity of his troubles but also a stressor in its own right.

Complex cases of PTSD presenting with hallucinatory experiences can be effectively treated with pharmacotherapy and supportive psychotherapy provided a good doctor-patient relationship is established and adverse medication effects rapidly dealt with. A cognitive framework and a Rorschach test can be valuable in deepening the understanding of individuals and obtaining a personalized view of their functioning and character dynamics. A biopsychosocial approach is essential in integrating all aspects of the patients' history in a meaningful way in order to provide adequate help.

Patient's perspective

"My life situation can't seem to get any better. I haven't had any support from anyone in all my life. Leaving home to go anywhere nowadays is hard and I can't seem to be able to stay anyplace else for a long time either. Just getting to the hospital [where the follow-up appointments are held] makes me very nervous, especially the minute I walk in. Can't seem to stay in place at all, just keep pacing while waiting for my appointment. I am only able to open up somewhat to my doctor, whom I thank for his support. Staying in hospital was close to impossible; I was very stressed and particularly concerned for my children, not being able to be close to them. I still need to have them near-by. Getting the MRI scan was also a stressful experience, confined in a small space with all that noise for so long. I succeeded only after getting extra medication.

I hope that things will get better. I don't trust anyone for any help any more; they should have helped me earlier."

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

stands for 'Post Traumatic Stress Disorder'

for 'Verbally Accessible Memory'

for 'Situationally Accessible Memory'

Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, Braff DL: Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1996, 39: 839-844. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00314-2.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, Emsley RA, Stein DJ: Linking Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Psychosis: A Look at Epidemiology, Phenomenology, and Treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003, 191: 675-10.1097/01.nmd.0000092177.97317.26.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Nutt DJ: The psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000, 61: 24-29.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brewin CR, Holmes EA: Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003, 23: 339-376. 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3.

Wilson JP, Keane TM: Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. 2004, The Guilford Press

Google Scholar

Ehlers A, Clark DM: A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000, 38: 319-345. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and direction offered by the department's chair, Professor Ioannis Giouzepas who places the utmost importance in creating a suitable therapeutic environment for our patients and a superb learning environment for the SHO's and registrars in his department.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

2nd Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Hospital of Thessaloniki, 196 Langada str., 564 29, Thessaloniki, Greece

Georgios D Floros, Ioanna Charatsidou & Grigorios Lavrentiadis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Georgios D Floros .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GF was the attending SHO and the major contributor in writing the manuscript. IC performed the psychological evaluation and Rorschach testing and interpretation. GL provided valuable guidance in diagnosis and handling of the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Floros, G.D., Charatsidou, I. & Lavrentiadis, G. A case of PTSD presenting with psychotic symptomatology: a case report. Cases Journal 1 , 352 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-352

Download citation

Received : 12 September 2008

Accepted : 25 November 2008

Published : 25 November 2008

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-352

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ziprasidone

- Psychotic Disorder

- Amisulpride

- Hallucinatory Experience

Cases Journal

ISSN: 1757-1626

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.58(6); 2020 Nov

Work-related post-traumatic stress disorder: report of five cases

Stefano m. candura.

1 Occupational Medicine Unit, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Sciences, University of Pavia, Italy

2 Occupational Medicine Unit, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri IRCCS, Institute of Pavia, Italy

Emanuela PETTENUZZO

Claudia negri.

3 Psychiatry Service, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri IRCCS, Institute of Pavia, Italy

Alessia GALLOZZI

Fabrizio scafa.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may arise after events involving a risk to physical integrity or to life, one’s own or that of others. It is characterized by intrusive symptoms, avoidance behaviors, and hyper-excitability. Outside certain categories (e.g., military and police), the syndrome is rarely described in the occupational setting. We report here five unusual cases of work-related PTSD, diagnosed with an interdisciplinary protocol (occupational health visit, psychiatric interview, psychological counselling and testing): (1) a 51-yr-old woman who had undergone three armed robbery attempts while working in a peripheral post office; (2) a 53-yr-old maintenance workman who had suffered serious burns on the job; (3) a 33-yr-old beauty center receptionist after sexual harassment and stalking by her male employer; (4) a 57-yr-old male psychiatrist assaulted by a psychotic outpatient; (5) a 40-yr-old woman, sales manager in a shoe store, after physical aggression by a thief. All patients required psychiatric help and pharmacological treatment, with difficulty of varying degrees in resuming work. We conclude that PTSD can develop even in professional categories generally considered to be at low risk. In such cases, a correct interdisciplinary diagnostic approach is fundamental for addressing therapy and for medico-legal actions.

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric condition which may develop after a terrifying event, usually involving a risk to physical integrity or to life, one’s own or of other people. Clinically, PTSD is characterized by: re-experience of the event with recurrent and intrusive recollections, distressing dreams, nightmares and flashbacks; avoidance of situations recalling the event; hyper-arousal causing difficulty in falling asleep or concentrating, or exaggerated startle response 1 , 2 , 3 ) .

PTSD is common in military personnel, especially after combat experiences. Other occupations at risk include police officers, firefighters, war correspondents, and health workers (mostly in emergency and intensive care units). Outside of these categories, work-related PTSD is rarely observed 4 ) .

In the occupational setting, PTSD should be differentiated by adjustment disorder (AD: a much more common diagnosis), that is another mental health condition occurring in response to a stressor, in which a number of life changes act as precipitants. Even though DA is less severe than PTSD, patients with DA display either marked distress or impairment in functioning (inability to work or perform other activities) 2 , 5 , 6 ) .

PTSD is a substantial medical and economic burden, and it has recently been highlighted as a public mental health priority 7 ) . To provide new insight which might facilitate prevention and diagnosis of work-related PTSD, we describe a series of patients, employed in occupations considered to be low risk, among whom the disorder was identified utilizing an interdisciplinary diagnostic protocol.

Patients and Methods

We report five outpatients (three females and two males, all Caucasian) who required a specialist assessment at the Occupational Medicine Unit of our Institute, for psychological health problems related to violence and/or job stress in the workplace.

The diagnostic process began with an evaluation by an occupational health specialist: for each patient a careful work history was collected, as well as family, social, physiological and pathological anamnesis. This step was followed by a complete physical examination.

Subsequently, the diagnostic protocol, developed by our group over the years, included: psychological counselling; Cognitive Behavioral Assessment 2.0 (CBA-2.0); complete personality test MMPI-2 (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2); SCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), axis I and II; Short-Negative Acts Questionnaire (S-NAQ); Maugeri Stress Index-reduced form (MASI-R); psychiatric visit 5 , 8 , 9 ) .

The CBA-2.0 is an automated assessment package investigating the cognitive-verbal response system. It includes ten primary scales consisting of: (1) self-reports and questionnaires aimed at identifying and specifying patients’ problems; (2) a group of programs and logical rules, implemented on personal computers, providing an editor with items, questionnaire scoring and an analysis of responses; (3) an intelligent program which analyzes the responses emerging from the questionnaires and forms hypotheses for the selection of secondary scales and for further assessment 10 ) .

Scales 1 and 4 are autobiographical files that investigate educational and school history, current conditions of coexistence, significant emotional relationships and related problems, general health status, eating and sleeping habits, reported psychological problems and the motivation for a possible psychological treatment. Scales 2 (20 items), 3 (20 items) and 10 (10 items) assess anxiety. Scale 5 (48 items) evaluates some stable personality dimensions such as introversion-extroversion, emotional stability, maladjustment and antisociality, simulation and social naivety. Scale 6 (30 items) provides an assessment of stress and psychophysiological disorders. Scale 7 (58 items) assesses fears. Scale 8 (24 items) assesses depressive symptoms. Finally, scale 9 (21 items) analyzes obsessions and compulsions.

The MMPI-2, the updated and standardized version of the MMPI test, assesses the most important structural features of personality and emotional disorders. It includes 567 questions on different topics: general health, neurological conditions, cranial nerves, motility and coordination, sensitivity, vasomotor function, trophism, speech, secretory functions, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems, habits, family and marital situation, professional activity, education, sexual, social and religious behavior, attitudes towards politics, law and order, morality, masculinity, femininity, presence of depression, manic, obsessive and compulsive disorders, presence of hallucinations, illusions, delusions, phobias, sexual sadistic and masochistic trends. Patients are required to respond to items with “True” or “False”; all omissions and items with dual response are considered as a response “I don’t know.” The usefulness of information obtained through the MMPI-2 depends on the ability of the subject to understand instructions, carry out the required task, understand and interpret the content of the items, and record the answers correctly. To calculate the scores, a computer program and a manual scoring are available 11 , 12 ).

Although MMPI-2 was born in a clinical context, thanks to the fact that it can study both normal and pathological personality characteristics, its administration proves useful also in the occupational and forensic field.

The SCID is a method that, based on a specific protocol, attributes specific symptoms, on which the examiner focuses, to the different disease conditions. For axis I, the process starts with patient history and leads to evaluate the presence of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression. The axis II consists of a self-report questionnaire followed by an interview regarding critical items of the questionnaire, to identify personality disorders and mental retardation 2 ) .

The S-NAQ is a psychometrically sound and easy to use instrument to identify targets exposed to varying degrees of workplace bullying. It consists of nine questions on specific negative behaviors, measuring exposure to harassment within the last six months. Patients score the frequency of each negative act according to the following response categories: 1-Never, 2-Rarely, 3-Monthly, 4-Weekly, and 5-Daily 13 ) .

The MASI-R is a multidimensional self-report questionnaire to evaluate job-related stress factors, assessing the impact of job strain on a team or on a single worker. It is composed of 37 items with response on a Likert scale from 0 to 5, and two visual analogues graded 0–100. The tool consists of four scales [Wellness (7 items), Resilience (16 items), Social support (5 items), and Coping (5 items)] and a Lie control scale (4 items). The two visual analogues ask the subject to express an evaluation of satisfaction in the workplace (Analog A) and outside of work (Analog B), thus allowing a comparison between these two important life areas. The instrument provides a reliable and valid measure, useful for early identification of stress levels in workers or in a team along the eustress–distress continuum 14 ) .

At the end of the tests, the patients met a clinical psychologist with specific experience in the field of work psychology, in order to deepen the knowledge of their interpersonal dynamics and to outline their personality structure. The interview was mainly focused on work issues, without neglecting to explore family and social life. The psychological interview also provided the opportunity to critically re-evaluate the responses provided by the subject to psychometric tests.

The psychiatric visit included psychiatric history (family and personal) and mental status assessment (speech, emotional expressiveness, thought and perception, cognitive functions). The answers to psychological tests were again discussed. The psychodiagnosis were formulated according to the DSM-5 criteria.

Informed consent was obtained from each subject, and the ethics committee of ICS Maugeri IRCCS approved the utilization of the patients’ clinical data (in anonymous form) for the present scientific report.

Female, 51-year-old. No psychiatric familiarity. Married with daughter and son. Nothing relevant in the previous medical history (in particular, no psychiatric record). After completing her studies (high school degree), she started working at the age of 20, initially as a typographer, then as a substitute teacher in kindergarten, and later as a clothing shop assistant.

At age 28 hired by the Italian postal service. After working as a postwoman and front clerk, at 41 she was promoted to director of a peripheral post office. She reported stressful working conditions: lack of preliminary training and professional updating, work overload, frequent overtime, lack of collaborators, occasional hostile behavior from customers, difficulty in commuting, poor support from hierarchical superiors and, above all, lack of security measures.

During the two years preceding our evaluation, the patient, while at work, underwent an armed robbery and two similar, failed attempts (the first time the woman herself managed to lock the door before the entry of the robbers, the second the attackers fled as the alarm system had gone off). As a consequence, she developed a continuous state of anxiety and emotional tension in terror of new attacks, insecurity, fear of going to work (with the need to be taken to and from work by her husband), hyper-arousal in circumstances evoking the working context, panic attacks, and sleep disturbances with nightmares. At this time, a diagnosis of PTSD was formulated by a private psychiatrist.

After a month of absence from work, the patient obtained a job transfer to a larger and less decentralized postal office, with partial improvement of disturbances, but considerable difficulties in adapting to the new situation, with repercussions on social and private life.

At the time of our consultation, the patient was on sick leave and on fluoxetine therapy. Nothing relevant on physical examination. Psychological counselling, psychiatric assessment, CBA-2.0, MMPI-2, and SCID revealed persisting work-related emotional distress, anxious-depressive state (with asthenia, pessimism, and distrust), sleep disturbances, impaired job performance with sense of guilt and inadequacy. Absence of cognitive impairment and pathological personality traits. Defense systems preserved. The patient reported negative behaviors at S-NAQ. MASI-R scores indicated high perceived work-related stress, poor job satisfaction, low coping and no support from colleagues.

Final diagnosis was adjustment disorder with anxiety and depressed mood in pre-existent PTSD (not completely resolved). The patient was referred to the territorial psychiatric service, with the suggestion to resume working only after the reduction of occupational stress factors.

Male, 53-yr-old. Mother with anxiety-depressive syndrome. Married with a son. Nothing relevant in physiological anamnesis. After completing his studies (middle school degree), he worked from the age of 17 in the metalworking sector for several employers, as carpenter, pipe maker and welder, suffering four traumatic accidents at work, with loss of distal phalanges of the second, third and fourth fingers of the right hand, as well as two fractures of the right radius. Additionally, he underwent bilateral inguinal hernioplasty and lumbar microdiscectomy.

At age 51, he started working for a large company, dealing with the installation and maintenance of chemical, oil and food plants. Two years before our evaluation, the patient was enveloped by a flare of methane while carrying out structural adjustments in a fuel depot, suffering second and third degree burns on 40% of the body surface. He was hospitalized in a burn center, where serious infectious complications (cutaneous and respiratory) occurred with the need for mechanical ventilation. The burns required multiple skin grafts, and numerous cycles of physiokinesitherapy to recover limb mobility.

After these events, the subject (without previous psychiatric record) developed anxiety with dysphoric mood, phobia, brooding with intrusive thoughts, sleep disturbances with nightmares, significant social distress (with fear to show the burn outcomes). He started private psychotherapy and treatment with anxiolytics and antidepressants. Despite this, the symptoms were still present and serious at the time of our observation. On physical examination: extensive, partly retracting dyschromic scars (left ear, neck, upper limbs, left hip and buttock). The patient (who was on sick leave) told us to have all mirrors and reflecting surfaces removed from his house, to avoid seeing his scars.

Psychological counselling and psychiatric assessment, led to the diagnosis of PTSD (with thymic axis oriented in depressive direction). Absence of cognitive impairment and pathological personality traits. Defense systems adequate. The patient did not report negative behaviors at S-NAQ. MASI-R scores indicated high job satisfaction, but modest support from colleagues.

We advised the patient to continue psychotherapy, and to return to work gradually, and followed by the company occupational physician.

Female, 33-yr-old. No psychiatric familiarity. Married without children. Nothing relevant in physiological and remote pathological anamnesis (in particular, no psychiatric record). After completing her university studies (philosophy degree), she worked from the age of 25 as a receptionist and assistant manager in several beauty centers.

Problems started 14 months before our evaluation, when the woman ended a love affair with her employer, who, from that moment, began to victimize her, both in and out of work: marginalization, threats, humiliations, blackmail, stalking, heavy sexual harassment. She developed anxiety, sense of guilt, loss of personal self-esteem, insomnia, intrusive thoughts, hyper-alertness, avoidance behaviors, compulsive actions of personal cleansing, self-injurious thoughts, and physical problems (loss of appetite, vomiting, weight loss, and menstrual irregularities). She took alprazolam for a couple of weeks, without benefit.

The patient quit the job, filed a complaint with the police, and asked for help from the unions and a center for violence against women. The persecution stopped, and the woman entered a psychological support program. In the meantime, she started a new job at a dental office with administrative and secretarial duties. The disturbances improved. However, at the time of our evaluation, she still reported anxiety, depressed mood, fear, brooding, sense of guilt and inadequacy. Nothing relevant on physical examination. Psychological counselling and psychiatric assessment led to the diagnosis of PTSD (in ameliorative evolution). Absence of cognitive impairment and pathological personality traits. Defense systems adequate. S-NAQ and MASI-R scores indicated good adaptation to the new job, with good support from the new employer.

Male, 57-yr-old. No psychiatric familiarity. Married with a son. Suffering from arterial hypertension (in pharmacological treatment) and recurrent lumbosciatalgia (two previous discectomy interventions). No previous psychiatric record. After completing his university studies (medical degree and specialization in psychiatry), he worked as a psychiatrist in hospital and territorial services. From age 47, head of a public outpatient unit.

Thirteen months before our evaluation, he was physically attacked by a psychotic patient, resulting in the fracture of two right ribs with pulmonary contusion. During the attack, he managed to avoid worse injuries by fleeing to barricade himself in another room. The attacker returned to look for him in the following days with a threatening attitude, until he was subjected to mandatory medical treatment.

After two months of absence, the psychiatrist resumed working in a different town, with difficulties in commuting and in adapting to the new situation. At the time of our evaluation, he was on sick leave again and on paroxetine therapy. Nothing relevant on physical examination (except the scar outcomes of previous operations on the spine). Psychological counselling, psychiatric assessment, CBA-2.0, MMPI-2, and SCID disclosed profound distress with anguish, depressed mood with crying fits, loss of personal self-esteem, persecution phobia (for himself and his family), re-experience of the event with intrusive recollections, insomnia with recurrent nightmares, remarkable social and occupational difficulties. Absence of cognitive impairment and pathological personality traits. Defense systems sufficiently adequate. The patient reported negative behaviors at S-NAQ. MASI-R scores indicated high perceived work-related stress, poor job satisfaction, low coping and no support from colleagues.

Final diagnosis was PTSD. We advised the patient to start psychotherapy, and to resume working only after clinical improvement and reduction of occupational stressful factors.

Female, 40-yr-old. Mother with bipolar syndrome. Married with a son. Nothing relevant in the previous medical history (in particular, no psychiatric record). After completing her studies (high school degree), she started working at the age of 20, initially as a bartender, then as sales assistant in various shops. From age 29, she worked in a large shoe store, where she was subsequently promoted to sales manager.

Six years before our evaluation, the woman tried to intercept a thief who had stolen some goods. As a result, she was physically attacked by him, reporting multiple contusions, distraction of the right shoulder, and sprain of the fourth finger of the right hand. Consequently, she developed anxiety, persistent discomfort and concern, continuous state of alert, intrusive thoughts, recurring nightmares, and psychosomatic disturbances (headache, tachycardia, dyspepsia, and menstrual irregularities). She consulted a psychiatrist, who formulated the diagnosis of severe anxiety-phobic syndrome, and started psychotherapy and psychoanalysis sessions.

The clinical picture slightly improved, and the patient resumed working after a couple of months. At this point, she began to be harassed by two hierarchical superiors, without apparent reason: physical and verbal attacks, denigration and humiliation (even in front of customers), obstructionism, disciplinary measures for futile reasons. She also reported degradation with a change of work place, then revoked after legal action.

At the time of our evaluation, the woman was on sick leave and on alprazoloam therapy. Nothing relevant on physical examination. Psychological counselling, psychiatric visit, CBA-2.0, MMPI-2, and SCID revealed work-related emotional distress, apathy, anxious-depressive state (with very low self-esteem and crying fits), poor sleep quality, and persistence of the psychosomatic disturbances. Absence of cognitive impairment and pathological personality traits. Defense systems preserved. The patient reported serious negative behaviors at S-NAQ. MASI-R scores indicated high perceived work-related stress, absence of job satisfaction, low coping and no support from colleagues.

Final diagnosis was pre-existent PTSD (not completely resolved) and adjustment disorder (with anxiety and depressed mood), likely resulting from mobbing at work. We advised the patient to continue psychiatric treatment. Work resumption was judged extremely difficult, due to the persistence of occupational stress factors.

Medico-legal actions

The cases were reported to the Judicial Authority, as established by the Italian Penal Code, and referred to the Italian Workers’ Compensation Authority (INAIL).

Work-related psychological trauma is quite common. However, diagnosing psychiatric disorders caused by occupational stress is not simple: the evaluation is mostly based on the patient’s self-reported symptoms, and hospital physicians do not usually have the means to verify directly the existence of stressful agents in the workplace. For various reasons, patients may hide or minimize their symptoms (for example, out of shame or fear of losing their job). Conversely, they may be induced to emphasize them (sometimes even unconsciously), in an attempt to get compensation for the damage suffered or other benefits. To overcome, at least in part, this difficulty, our group has developed an interdisciplinary diagnostic protocol that comprises the examination of the patient by three specialists (occupational physician, psychiatrist and occupational psychologist), and the administration of psychometric tests. Over the past twenty years, this approach has proven useful in diagnosing adaptation disorder and other psychiatric disturbances caused by mobbing and other work-related stressors, differentiating these conditions from non-work-related psychiatric disorders 5 , 9 ) . The five cases reported here indicate that the same protocol is also useful for diagnosing PTSD, a condition rarely found in outpatient occupational medicine practice. In addition, the five cases are particularly interesting for the unusual jobs and circumstances in which the triggering traumatic events occurred.

The first is a middle-aged woman in whom the disorder arose after three armed robbery attempts. Indeed, exposure to more than one robbery increases the rates of PTSD 15 , 16 ). Other recognized risk factors, to which our patient was exposed, are proximity to the robber and the presence of weapons 17 , 18 ) .

In recent years, bank and postal robberies have been less frequent, due to increased security measures 17 , 19 ) . Other businesses are now more exposed, such as small retail shops and all night convenience stores 20 ) . Our case indicates that peripheral post offices may also be at high risk.

The second case is the victim of a terrible accident at work, causing extensive burns, life-threatening complications, and disfiguring scars. Previous studies indicate that PTSD may be identified in up to 30% of such patients, stressing the need for a dedicated staff psychiatrist in modern burn centers 21 , 22 ) . In burn victims, life threat perception is the strongest predictor for PTSD occurrence, followed by acute intrusive symptoms and pain associated with the injuries 23 ) . Scarring involving the face and/or other visible body areas (like in our patient) is another important risk factor 24 ) .

In the third subject (a 33-yr-old woman), the PTSD was the consequence of psychological aggression, sexual harassment, and stalking perpetrated by a male employer. Violence against women is a substantial mental health concern worldwide. Younger women are more at risk. Among victims, PTSD, depression and substance abuse are potential and even likely mental health outcomes 25 , 26 ) . Our patient fought back: she changed job and asked for help (police, unions, antiviolence center, and psychological support), obtaining the cessation of persecution and, consequently, a clinical improvement. This indicates that prompt counteractions can favorably influence the evolution of PTSD in female violence victims.

In the last two patients, the syndrome was the result of physical violence and personal injuries on the workplace. The fourth case is a psychiatrist. Mental health professionals may be exposed to aggression from patients, and report high levels of PTSD symptoms 27 ) . Our observation, however, is quite unusual in that the acts of violence generally take place in the hospital (emergency room or psychiatric wards) rather than in territorial outpatient services, involving nursing staff more often than doctors 28 ) .

The fifth subject was assaulted by a shoplifter she had tried to intercept. Similarly to case one, the PTSD was the consequence of a criminal act. For both these women, work resumption was particularly difficult, and they subsequently developed an overlapped adjustment disorder, thus receiving a double psychodiagnosis. This is uncommon, since people who have experienced a traumatic event are usually diagnosed as either suffering from PTSD or from AD, however it should not be considered surprising for two reasons: (i) workers suffering from PTSD and other stress-related disturbances readapt with difficulty to their previous job 29 ) ; (ii) in many cases, there is a co-morbidity between PTSD and other disorders (such as depression, anxiety and substance abuse). For example, in a study of combat veterans, nearly 80% of PTSD cases met the criteria for at least one personality disorder 30 ) . Our diagnostic conclusions were based on an analysis of the chronological appearance of symptoms: both patients first manifested the PTSD, then benefited from a period of sick leave, started treatment with partial improvement of disturbances, returned to the same job encountering notable difficulties, and only thereafter did they develop the AD.

The case of the fifth patient is singular, since she was subjected to mobbing after resuming working. Indeed, women quite often experience hostile behavior after returning from sick leave or maternity 5 ) . Mobbing (or bullying) is one of the most formidable psychosocial risk factors found in the workplace. It consists of repeated and prolonged psychological harassment, towards a worker, due to hostile actions usually carried out by a superior (vertical mobbing or bossing) or by a small group of colleagues (horizontal or transversal mobbing), exercised through aggressive, persecuting and detrimental behaviors of personal and professional dignity, capable of provoking damage to individual psychophysical health 31 ) .

Treatment of PTSD includes psychological and pharmacological interventions. Most guidelines identify trauma-focused psychological interventions (such as cognitive behavioral therapy) as first-line treatment options 32 , 33 ) . In the acute phase following the traumatic event, it is important that the individual regains emotional control, restores interpersonal communication and group identity, recuperates a sense of empowerment through participation in work, and strengthens hope and the expectation of recovery. Such an approach, known as psychological first aid, has given satisfactory results 34 ) . Pharmacological treatments include antidepressants (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors), sympatholytic drugs such as alpha-blockers, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines 1 , 35 ) . In this context, the correct diagnostic assessment of work-related PTSD by hospital occupational medicine units can be very useful to address patients towards an appropriate therapeutic path, in order to promote their psychological well-being and work reintegration.

The evolution of work-related PTSD (as well as of other conditions due to occupational stress) is complicated and difficult to predict. In a significant portion of patients, the disorder tends to improve over time, even in the absence of treatment. However, in many others the symptoms persist even after several years, making return to work difficult or impossible 29 , 36 ) , as in the cases reported here.

The present report highlights the need for preventive interventions. Prevention of work-related PTSD includes a sound organizational and psychosocial work environment, systematic training of employees, social support from colleagues and managers, and a proper follow-up of employees after a critical event 37 ) .

The five cases were referred to the appropriate legal authorities. Work-related stress and resulting disease has complex medico-legal implications, in the penal, civil, and insurance contexts 38 ) . For example, the Italian Workers’ Compensation Authority (INAIL) includes “mental and psychosomatic illnesses due to work organization dysfunction (organizational coerciveness)” among the inventory of occupational diseases (Italian Ministry of Labour and Social Policy: Decree 27th April 2004). Thus, an accurate diagnostic procedure is essential not only for clinical (prognostic and therapeutic-rehabilitative) reasons, but also for the possible demonstration of the causal link between traumatic events in the workplace and suffered mental damages 5 ) . At the time this article is written, the medico-legal evaluation of the five reported cases is still ongoing. A previous explorative follow-up study indicated that our certifications lead to outcomes favorable to the worker, after litigations (or extrajudicial agreements) with INAIL and/or the employer, in at least half of the cases 29 ) .

PTSD can arise as a consequence of accidents or assaults in the workplace, even in professional categories generally considered to be at low risk. In such cases, a correct interdisciplinary diagnostic approach is fundamental for addressing therapy and for medico-legal fulfillments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Broughton for linguistic revision.

Case Example: Terry, a 42-year-old Earthquake Survivor

Through the use of repeated imaginal exposures, Terry slowly began to feel more conformable with discussing the trauma and telling people about his experience.

About this Example

Terry's Story

Terry, a 42-year-old earthquake survivor, had been experiencing PTSD symptoms for more than eight years. Terry consistently avoided thoughts and images related to witnessing the injuries and deaths of others during the earthquake. Throughout the years, he began spending an increasing amount of time at work and filling his days with hobbies and activities.

By the time he sought treatment, Terry had managed to fill his entire week with various obligations in order to keep his mind occupied and to minimize the possibility that he would think about the traumatic event. He also worked hard to convince others that the earthquake had not affected him. He did this by avoiding people that knew he had gone through this experience and by quickly changing the topic when it came up. However, he found that whenever he had free time, he would have unwanted intrusive thoughts and images about the earthquake. In addition, he was having increasingly distressing nightmares that were causing him to lose several hours of sleep each night. His repeated violent awakenings throughout the night had also disturbed his wife’s sleep, resulting in them no longer sharing a bedroom. Terry found that the harder he worked to avoid these thoughts, the more frequent they would become, and that they were getting stronger each day. He feared that if he thought about the memory he would lose control of his emotions and would not be able to cope. He was concerned that the fear and panic that occurred when he was reminded of the trauma would last forever. By avoiding thoughts about the memory, he never allowed himself to test out his predictions. Furthermore, through his repeated avoidance of the trauma memory, his fear continued to grow.

Terry eventually sought treatment because his symptoms were significantly impairing his work and family life. After receiving a thorough assessment of his PTSD and comorbid symptoms, psychoeducation about PTSD symptoms, and a rationale for using imaginal exposures, Terry received a number of sessions of imaginal exposure. With encouragement from his therapist, he engaged with the trauma memory in session by providing a detailed account of what he witnessed during the earthquake. The therapist prompted him to begin the account at the point at which he initially was aware that the earthquake was happening. She prompted him to describe in detail where he was at the time, who he was with, what he saw, how it ended, the sensations he had, and importantly, what he was thinking and feeling at the time. With each recounting, the therapist asked Terry to provide even more sensory and emotional details about the experience to facilitate habituation to the memory and to increase his mastery of his anxiety related to facing it. These retellings were recorded so that Terry could listen to the account outside of session for homework.

By engaging with the memory in a systematic manner and not allowing himself to escape or avoid it, he recognized that his fear and anxiety subsided as the exposures went on. Furthermore, he was able to test some of the predictions he had made about what would happen if he allowed himself to think about the trauma. He recognized that he could fully maintain control of his emotions and that, although he felt fear and anxiety throughout the exposure, these feelings quickly passed. Through the use of repeated imaginal exposures, Terry slowly began to feel more comfortable with discussing the trauma and telling people about his experience. He no longer feared the memory and was able to recognize that the memory itself was not dangerous.

Excerpt from an In-Session Imaginal Exposure

The following case example is an excerpt from an imaginal exposure with a client who was in a motor vehicle accident with his wife and young child, in which his child was killed. Although only part of the exposure is provided, when conducting imaginal exposures in session, the exposure should be conducted until the end of the memory and repeated for at least 45 to 60 minutes. The example below was the first imaginal exposure conducted with this client. With the first exposure it is common for a client’s Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) rating to be elevated throughout the entire memory. With repetition during the session, as well as across several sessions, the memory will elicit lower distress ratings and it will take a shorter duration to have the distress rating reduce across the exposure.

Therapist: Let’s start by having you close your eyes and sit comfortably in your chair. I’d like you to go back to the memory of what happened during the accident. Try to talk about it as if you were back in the moment or as if it were happening right now. Remember to talk in first person and not as if you were watching the event take place from another person’s perspective. You may experience a number of strong emotions, but I want you to remember that it is just a memory and that a memory itself can’t cause you any harm. You are safe here in the office. The memory alone isn’t dangerous. During the exposure I’m going to ask you how distressed you are using the SUDS ratings. Try to tell me as quickly as you can and go right back into the memory. If you feel overly afraid or anxious, you may open your eyes, but try to stay with the memory. However, do your best to keep them closed throughout the exposure. During the exposure I won’t be speaking much, except to help keep you moving forward. We will talk about it when you are done. Are you ready to start?

Client: Yes.

Therapist: What is your SUDS just before we start?

Client: 80.

Therapist: Okay. Take yourself back to the day of the accident. What happened just before?

Client: I am driving home from visiting my brother-in-law and his family. It is getting dark and it is drizzling. It’s hard to see the lines dividing my lane from oncoming traffic. I’m looking in my rearview mirror to check on my son who is falling asleep in his car seat. My wife is sitting beside me and asking me about something that her brother had said to me while she was in the kitchen. I’m looking in the rearview mirror again and I see a car. It’s coming toward us extremely fast. Its high beams are on and it’s flashing them at me. Now I see another car just behind it. They keep on cutting each other off. They are getting very close to my car and are trying to pass me. I try to move over to let them pass, but there is no shoulder on the road for me to slow down or pull onto. My wife is very nervous. She turns to look out the rear windshield. I’m shaking and I don’t know what to do. The cars are very close now. They are just behind me to the right. They are trying to squeeze past me on the right side, between me and the guardrail.

I try to let them pass by moving a bit into the oncoming traffic lane. Their high beams are hitting my mirror and making it hard for me to see.

Therapist: What’s your SUDS rating?

Client: 100. They are finally passing me on my right side. My wife is screaming at me to move over. I hear a loud horn. My car is still partly in the oncoming traffic lane . . . (The client pauses for a number of seconds.)

Therapist: You’re doing great. Keep going.

Client: The second car is now passing and I hear the horn again. It’s loud. Like a big truck. I still can’t see very well and I’m sweating. My wife is saying something to me but I can’t make out what she is saying. The horn is getting louder and it keeps sounding over and over again. Even with the second car passing me, something is still blinding me. I realize that it is a truck coming toward us and that I’m in its way because I moved into its lane. I try to swerve back into my lane, but it is too late. (The client, now visibly distressed, is having trouble continuing. He is crying and shaking his head back and forth, as if saying “no”.)

Therapist: Remember, it’s just a memory. You are safe here in the office; keep going.

Client: The truck hits us on the back left side door, the seat where my son was sitting. (The client is sweating and becoming tearful.)

Therapist: I know this is hard, but stay with the memory. (The therapist notes this section of the memory as a potential hot spot. The client pauses for a few more seconds and then continues.)

Client: I hear a loud crash. The car is spinning violently. My wife keeps screaming and the car keeps spinning. I can’t see anything and all I hear is my wife’s screaming. The car finally stops. I’m bleeding from my left arm and the window is broken. I look at my wife beside me and she is crying. I ask her if she is hurt. She says no. We simultaneously look at the backseat to check on our son. His car seat is turned in the backseat and he is lying sideways in it. His body is twisted in the car seat. He isn’t moving and he isn’t breathing. He isn’t making a sound. I’m screaming for my wife to call 911, but she is just sitting there sobbing. I crawl over the seat and now I’m in the backseat with my son. I want to hold him but I know I shouldn’t move him. I fumble to find my cell phone in my pocket and call 911. The dispatch operator answers almost immediately. She asks if I need firefighters, an ambulance, or the police, but I can’t answer. I am crying and I keep repeating, “It was an accident.” My wife is screaming now. She keeps on saying, “My baby is dead, my baby is dead.” The dispatch operator asks for my location. I tell her I’m just east of Exit 92 heading west on the I90. She tells me that help is on the way. She’s now asking me to check on the baby. I tell her that he’s not breathing and she tells me not to touch him and that the ambulance will be there soon. I can hear sirens. The sound is getting louder and louder. It sounds as if there are 100 police cars heading toward us. The police and paramedics arrive. They take my wife and I to the back of an ambulance and turn us so we can’t see our car. The paramedics ask us if we are okay. I tell them we are fine, but my wife can’t stop crying. She is shaking and screaming. The paramedics see the cut on my arm and start to treat it. They tell me that it isn’t too deep and that I won’t need stiches. I keep asking about my baby, but the paramedics won’t give me a response. Finally, I see a police officer begin to move toward us. (The client pauses. He is tearful.)

Therapist: You’re doing great; what happened next?

Client: The police officer looks stoic. His face looks flat. He looks at my wife and I and says that he is very sorry. Our son did not survive the crash. My wife begins to scream again, “My baby is dead, my baby is dead.” Her crying seems out of control and the paramedics try to comfort her. I look at the officer with a blank stare and ask him what I’m supposed to do. I can’t feel anything. I feel empty. I know I’m supposed to cry, supposed to feel sad, supposed to feel something, but all I can do is ask the police officer what I’m supposed to do. The officer gives me the address of the hospital where my son is being taken and gives me instructions on how to claim his body from the morgue. I thank the police officer. He then asks me what happened. I tell him about the cars that were racing and the oncoming truck. The police officer takes my statement. He tells me that the truck driver was injured and taken to the hospital. I finish giving him my statement. Another police officer comes and asks my wife for her statement. She has calmed down by now. She returns to where I am sitting, on the back of the ambulance but doesn’t say anything. A police officer tells us that he will take care of getting us home. We get into his car, I give him our address and none of us speak for the entire ride.

Client: 70.

Therapist: I know how hard that was for you. You did a great job, and I appreciate you sharing that memory with me. I know at times it feels tough, but it will get easier each time.

Client: I didn’t think I was going to be able to continue.

Therapist: Sometimes it can feel that way, but it’s important to keep going. Remember, it is just a memory, and a memory on its own can’t hurt you. As we keep practicing these exposures you will feel less fear and anxiety. Eventually the memory will no longer cause you any fear. You should be really proud of what you just did. It took a lot of courage to talk about the accident so openly. How do you feel?

Client: I feel okay. A little anxious still.

Therapist: Do you think you could try that again?

Client: I think so.

Therapist: Okay, when you are ready, I want you to start again.

Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work

This case example is reprinted with permission from: Monson, C. M. & Shnaider, P. (2014). Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Other Case Examples

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Jill, a 32-year-old Afghanistan War Veteran

- Cognitive Therapy Philip, a 60-year-old who was in a traffic accident (PDF, 294KB)

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Mike, a 32-year-old Iraq War Veteran

- Narrative Exposure Therapy Eric, a 24-year-old Rwandan refugee living in Uganda (PDF, 28KB)

- View PDF

- Download full issue

Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry

Post-traumatic stress disorder: a biopsychosocial case-control study investigating peripheral blood protein biomarkers.

- • Overlapping symptomology of PTSD with depression and anxiety presents diagnostic challenges.

- • EGF, tPA and IL-8 were differentially expressed in PTSD vs. control participants.

- • Using a biopsychosocial approach may improve PTSD diagnosis and treatment management.

- Previous article in issue

- Next article in issue

Cited by (0)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Case Examples. Examples of strongly and conditionally recommended interventions in the treatment of PTSD. Strongly Recommended Treatments. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Jill, a 32-year-old Afghanistan War veteran. Jill had been experiencing PTSD symptoms for more than five years.

This is a case example for the treatment of PTSD using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. It is strongly recommended by the APA Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD. Download case example (PDF, 108KB).

Complex cases of PTSD presenting with hallucinatory experiences can be effectively treated with pharmacotherapy and supportive psychotherapy provided a good doctor-patient relationship is established and adverse medication effects rapidly dealt with.

We report here five unusual cases of work-related PTSD, diagnosed with an interdisciplinary protocol (occupational health visit, psychiatric interview, psychological counselling and testing): (1) a 51-yr-old woman who had undergone three armed robbery attempts while working in a peripheral post office; (2) a 53-yr-old maintenance workman who had...

About this Example. The first case example about Terry documents the treatment of PTSD using Prolonged Exposure. The second is an example of in-session imaginal exposure with a different client. Prolonged Exposure is strongly recommended by the APA Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD. Download case study (PDF, 107KB).

This case-control study (n = 40) aimed to identify differences in peripheral blood biomarkers, and biomarker combinations, able to distinguish PTSD participants from controls, and examine in a biopsychosocial framework.