Have a language expert improve your writing

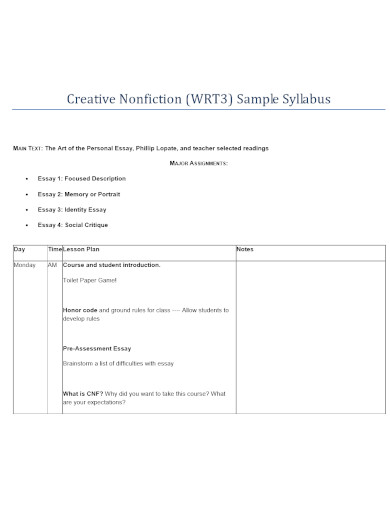

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

| Part | Content |

|---|---|

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.

A chronological approach can be useful when your essay is about a series of events. Don’t rule out other approaches, though—even when the chronological approach is the obvious one, you might be able to bring out more with a different structure.

Explore the tabs below to see a general template and a specific example outline from an essay on the invention of the printing press.

- Thesis statement

- Discussion of event/period

- Consequences

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

- Claim that the printing press marks the end of the Middle Ages

- Background on the low levels of literacy before the printing press

- Thesis statement: The invention of the printing press increased circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation

- High levels of illiteracy in medieval Europe

- Literacy and thus knowledge and education were mainly the domain of religious and political elites

- Consequence: this discouraged political and religious change

- Invention of the printing press in 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg

- Implications of the new technology for book production

- Consequence: Rapid spread of the technology and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible

- Trend for translating the Bible into vernacular languages during the years following the printing press’s invention

- Luther’s own translation of the Bible during the Reformation

- Consequence: The large-scale effects the Reformation would have on religion and politics

- Summarize the history described

- Stress the significance of the printing press to the events of this period

Essays with two or more main subjects are often structured around comparing and contrasting . For example, a literary analysis essay might compare two different texts, and an argumentative essay might compare the strengths of different arguments.

There are two main ways of structuring a compare-and-contrast essay: the alternating method, and the block method.

Alternating

In the alternating method, each paragraph compares your subjects in terms of a specific point of comparison. These points of comparison are therefore what defines each paragraph.

The tabs below show a general template for this structure, and a specific example for an essay comparing and contrasting distance learning with traditional classroom learning.

- Synthesis of arguments

- Topical relevance of distance learning in lockdown

- Increasing prevalence of distance learning over the last decade

- Thesis statement: While distance learning has certain advantages, it introduces multiple new accessibility issues that must be addressed for it to be as effective as classroom learning

- Classroom learning: Ease of identifying difficulties and privately discussing them

- Distance learning: Difficulty of noticing and unobtrusively helping

- Classroom learning: Difficulties accessing the classroom (disability, distance travelled from home)

- Distance learning: Difficulties with online work (lack of tech literacy, unreliable connection, distractions)

- Classroom learning: Tends to encourage personal engagement among students and with teacher, more relaxed social environment

- Distance learning: Greater ability to reach out to teacher privately

- Sum up, emphasize that distance learning introduces more difficulties than it solves

- Stress the importance of addressing issues with distance learning as it becomes increasingly common

- Distance learning may prove to be the future, but it still has a long way to go

In the block method, each subject is covered all in one go, potentially across multiple paragraphs. For example, you might write two paragraphs about your first subject and then two about your second subject, making comparisons back to the first.

The tabs again show a general template, followed by another essay on distance learning, this time with the body structured in blocks.

- Point 1 (compare)

- Point 2 (compare)

- Point 3 (compare)

- Point 4 (compare)

- Advantages: Flexibility, accessibility

- Disadvantages: Discomfort, challenges for those with poor internet or tech literacy

- Advantages: Potential for teacher to discuss issues with a student in a separate private call

- Disadvantages: Difficulty of identifying struggling students and aiding them unobtrusively, lack of personal interaction among students

- Advantages: More accessible to those with low tech literacy, equality of all sharing one learning environment

- Disadvantages: Students must live close enough to attend, commutes may vary, classrooms not always accessible for disabled students

- Advantages: Ease of picking up on signs a student is struggling, more personal interaction among students

- Disadvantages: May be harder for students to approach teacher privately in person to raise issues

An essay that concerns a specific problem (practical or theoretical) may be structured according to the problems-methods-solutions approach.

This is just what it sounds like: You define the problem, characterize a method or theory that may solve it, and finally analyze the problem, using this method or theory to arrive at a solution. If the problem is theoretical, the solution might be the analysis you present in the essay itself; otherwise, you might just present a proposed solution.

The tabs below show a template for this structure and an example outline for an essay about the problem of fake news.

- Introduce the problem

- Provide background

- Describe your approach to solving it

- Define the problem precisely

- Describe why it’s important

- Indicate previous approaches to the problem

- Present your new approach, and why it’s better

- Apply the new method or theory to the problem

- Indicate the solution you arrive at by doing so

- Assess (potential or actual) effectiveness of solution

- Describe the implications

- Problem: The growth of “fake news” online

- Prevalence of polarized/conspiracy-focused news sources online

- Thesis statement: Rather than attempting to stamp out online fake news through social media moderation, an effective approach to combating it must work with educational institutions to improve media literacy

- Definition: Deliberate disinformation designed to spread virally online

- Popularization of the term, growth of the phenomenon

- Previous approaches: Labeling and moderation on social media platforms

- Critique: This approach feeds conspiracies; the real solution is to improve media literacy so users can better identify fake news

- Greater emphasis should be placed on media literacy education in schools

- This allows people to assess news sources independently, rather than just being told which ones to trust

- This is a long-term solution but could be highly effective

- It would require significant organization and investment, but would equip people to judge news sources more effectively

- Rather than trying to contain the spread of fake news, we must teach the next generation not to fall for it

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Signposting means guiding the reader through your essay with language that describes or hints at the structure of what follows. It can help you clarify your structure for yourself as well as helping your reader follow your ideas.

The essay overview

In longer essays whose body is split into multiple named sections, the introduction often ends with an overview of the rest of the essay. This gives a brief description of the main idea or argument of each section.

The overview allows the reader to immediately understand what will be covered in the essay and in what order. Though it describes what comes later in the text, it is generally written in the present tense . The following example is from a literary analysis essay on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

Transitions

Transition words and phrases are used throughout all good essays to link together different ideas. They help guide the reader through your text, and an essay that uses them effectively will be much easier to follow.

Various different relationships can be expressed by transition words, as shown in this example.

Because Hitler failed to respond to the British ultimatum, France and the UK declared war on Germany. Although it was an outcome the Allies had hoped to avoid, they were prepared to back up their ultimatum in order to combat the existential threat posed by the Third Reich.

Transition sentences may be included to transition between different paragraphs or sections of an essay. A good transition sentence moves the reader on to the next topic while indicating how it relates to the previous one.

… Distance learning, then, seems to improve accessibility in some ways while representing a step backwards in others.

However , considering the issue of personal interaction among students presents a different picture.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarized in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, how to write the body of an essay | drafting & redrafting, transition sentences | tips & examples for clear writing, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Academic Editing and Proofreading

- Tips to Self-Edit Your Dissertation

- Guide to Essay Editing: Methods, Tips, & Examples

- Journal Article Proofreading: Process, Cost, & Checklist

- The A–Z of Dissertation Editing: Standard Rates & Involved Steps

- Research Paper Editing | Guide to a Perfect Research Paper

- Dissertation Proofreading | Definition & Standard Rates

- Thesis Proofreading | Definition, Importance & Standard Pricing

- Research Paper Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Essay Proofreading | Options, Cost & Checklist

- Top 10 Paper Editing Services of 2024 (Costs & Features)

- Top 10 Essay Checkers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- Top 10 AI Proofreaders to Perfect Your Writing in 2024

- Top 10 English Correctors to Perfect Your Text in 2024

- Top 10 Essay Editing Services of 2024

- 10 Advanced AI Text Editors to Transform Writing in 2024

- Personal Statement Editing Services: Craft a Winning Essay

- Top 10 Academic Proofreading Services & How They Help

Academic Research

- Research Paper Outline: Free Templates & Examples to Guide You

- How to Write a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- Research Methodology Guide: Writing Tips, Types, & Examples

- The 10 Best Essential Resources for Academic Research

- 100+ Useful ChatGPT Prompts for Thesis Writing in 2024

- Best ChatGPT Prompts for Academic Writing (100+ Prompts!)

- Sampling Methods Guide: Types, Strategies, and Examples

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Meaning & Examples

Academic Writing & Publishing

- Difference Between Paper Editing and Peer Review

- What are the different types of peer review?

- How to Handle Journal Rejection: Essential Tips

- Editing and Proofreading Academic Papers: A Short Guide

- How to Carry Out Secondary Research

- The Results Section of a Dissertation

- Checklist: Is my Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- Types of Research Articles to Boost Your Research Profile

- 8 Types of Peer Review Processes You Should Know

- The Ethics of Academic Research

- How does LaTeX based proofreading work?

- How to Improve Your Scientific Writing: A Short Guide

- Chicago Title, Cover Page & Body | Paper Format Guidelines

- How to Write a Thesis Statement: Examples & Tips

- Chicago Style Citation: Quick Guide & Examples

- The A-Z Of Publishing Your Article in A Journal

- What is Journal Article Editing? 3 Reasons You Need It

- 5 Powerful Personal Statement Examples (Template Included)

- Complete Guide to MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Book in APA Style | Format & Examples

- How to Start a Research Paper | Step-by-step Guide

- APA Citations Made Easy with Our Concise Guide for 2024

- A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Formatting Style (7th Edition)

- Top 10 Online Dissertation Editing Services of 2024

- Academic Writing in 2024: 5 Key Dos & Don’ts + Examples

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- MLA Works Cited Page: Quick Tips & Examples

- 2024’s Top 10 Thesis Statement Generators (Free Included!)

- Top 10 Title Page Generators for Students in 2024

- What Is an Open Access Journal? 10 Myths Busted!

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources: Definition, Types & Examples

- How To Write a College Admissions Essay That Stands Out

- How to Write a Dissertation & Thesis Conclusion (+ Examples)

- APA Journal Citation: 7 Types, In-Text Rules, & Examples

- What Is Predatory Publishing and How to Avoid It!

- What Is Plagiarism? Meaning, Types & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Dissertation & Thesis Introduction

- How to Cite a Book in MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Website in MLA Format | 9th Edition Rules

- 10 Best AI Conclusion Generators (Features & Pricing)

- Top 10 Academic Editing Services of 2024 [with Pricing]

- 100+ Writing Prompts for College Students (10+ Categories!)

- How to Create the Perfect Thesis Title Page in 2024

- Additional Resources

- Preventing Plagiarism in Your Thesis: Tips & Best Practices

- Final Submission Checklist | Dissertation & Thesis

- 7 Useful MS Word Formatting Tips for Dissertation Writing

- How to Write a MEAL Paragraph: Writing Plan Explained in Detail

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- The 10 Best Citation Generators in 2024 | Free & Paid Plans!

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- The 10 Best Free Character and Word Counters of 2024

- Know Everything About How to Make an Audiobook

- Mastering Metaphors: Definition, Types, and Examples

- Citation and Referencing

- Citing References: APA, MLA, and Chicago

- How to Cite Sources in the MLA Format

- MLA Citation Examples: Cite Essays, Websites, Movies & More

- Citations and References: What Are They and Why They Matter

- APA Headings & Subheadings | Formatting Guidelines & Examples

- Formatting an APA Reference Page | Template & Examples

- Research Paper Format: APA, MLA, & Chicago Style

- How to Create an MLA Title Page | Format, Steps, & Examples

- How to Create an MLA Header | Format Guidelines & Examples

- MLA Annotated Bibliography | Guidelines and Examples

- APA Website Citation (7th Edition) Guide | Format & Examples

- APA Citation Examples: The Bible, TED Talk, PPT & More

- APA Header Format: 5 Steps & Running Head Examples

- APA Title Page Format Simplified | Examples + Free Template

- How to Write an Abstract in MLA Format: Tips & Examples

- 10 Best Free Plagiarism Checkers of 2024 [100% Free Tools]

- 5 Reasons to Cite Your Sources Properly | Avoid Plagiarism!

- Dissertation Writing Guide

- Writing a Dissertation Proposal

- The Acknowledgments Section of a Dissertation

- The Table of Contents Page of a Dissertation

- The Introduction Chapter of a Dissertation

- The Literature Review of a Dissertation

- The Only Dissertation Toolkit You’ll Ever Need!

- 5 Thesis Writing Tips for Master Procrastinators

- How to Write a Dissertation | 5 Tips from Academic Editors

- The 5 Things to Look for in a Dissertation Editing Service

- Top 10 Dissertation Editing & Proofreading Services

- Why is it important to add references to your thesis?

- Thesis Editing | Definition, Scope & Standard Rates

- Expert Formatting Tips on MS Word for Dissertations

- A 7-Step Guide on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- 350 Best Dissertation Topic Ideas for All Streams in 2024

- A Guide on How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- Dissertation Defense: What to Expect and How to Prepare

- Creating a Dissertation Title Page (Examples & Templates)

- Essay Writing Guide

- Essential Research Tips for Essay Writing

- What Is a Mind Map? Free Mind Map Templates & Examples

- How to Write an Essay Outline: 5 Examples & Free Template

- How to Write an Essay Header: MLA and APA Essay Headers

What Is an Essay? Structure, Parts, and Types

- How to Write an Essay in 8 Simple Steps (Examples Included)

- 8 Types of Essays | Quick Summary with Examples

- Expository Essays | Step-by-Step Manual with Examples

- Narrative Essay | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay (Examples Included)

- Guide to a Perfect Descriptive Essay [Examples & Outline Included]

- How to Start an Essay: 4 Introduction Paragraph Examples

- How to Write a Conclusion for an Essay (Examples Included!)

- How to Write an Impactful Personal Statement (Examples Included)

- Literary Analysis Essay: 5 Steps to a Perfect Assignment

- Compare and Contrast Essay | Quick Guide with Examples

- Top AI Essay Writers in 2024: 10 Must-Haves

- 100 Best College Essay Topics & How to Pick the Perfect One!

- College Essay Format: Tips, Examples, and Free Template

- Structure of an Essay: 5 Tips to Write an Outstanding Essay

- 10 Best AI Essay Outline Generators of 2024

- The Best Essay Graders of 2024 That You Can Use for Free!

- Top 10 Free Essay Writing Tools for Students in 2024

Still have questions? Leave a comment

Add Comment

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Need editing and proofreading services.

- Tags: Academic Writing , Essay , Essay Writing

Writing an effective and impactful essay is crucial to your academic or professional success. Whether it’s getting into the college of your dreams or scoring high on a major assignment, writing a well-structured essay will help you achieve it all. But before you learn how to write an essay , you need to know its basic components.

In this article, we will understand what an essay is, how long it should be, and its different parts and types. We will also take a detailed look at relevant examples to better understand the essay structure.

Get an A+ with our essay editing and proofreading services! Learn more

What is an essay?

An essay is a concise piece of nonfiction writing that aims to either inform the reader about a topic or argue a particular perspective. It can either be formal or informal in nature. Most academic essays are highly formal, whereas informal essays are commonly found in journal entries, social media, or even blog posts.

As we can see from this essay definition, the beauty of essays lies in their versatility. From the exploration of complex scientific concepts to the history and evolution of everyday objects, they can cover a vast range of topics.

How long is an essay?

The length of an essay can vary from a few hundred to several thousand words but typically falls between 500–5,000 words. However, there are exceptions to this norm, such as Joan Didion and David Sedaris who have written entire books of essays.

Let’s take a look at the different types of essays and their lengths with the help of the following table:

How many paragraphs are in an essay?

Typically, an essay has five paragraphs: an introduction, a conclusion, and three body paragraphs. However, there is no set rule about the number of paragraphs in an essay.

The number of paragraphs can vary depending on the type and scope of your essay. An expository or argumentative essay may require more body paragraphs to include all the necessary information, whereas a narrative essay may need fewer.

Structure of an essay

To enhance the coherence and readability of your essay, it’s important to follow certain rules regarding the structure. Take a look:

1. Arrange your information from the most simple to the most complex bits. You can start the body paragraph off with a general statement and then move on to specifics.

2. Provide the necessary background information at the beginning of your essay to give the reader the context behind your thesis statement.

3. Select topic statements that provide value, more information, or evidence for your thesis statement.

There are also various essay structures , such as the compare and contrast structure, chronological structure, problem method solution structure, and signposting structure that you can follow to create an organized and impactful essay.

Parts of an essay

An impactful, well-structured essay comes down to three important parts: the introduction, body, and conclusion.

1. The introduction sets the stage for your essay and is typically a paragraph long. It should grab the reader’s attention and give them a clear idea of what your essay will be about.

2. The body is where you dive deeper into your topic and present your arguments and evidence. It usually consists of two paragraphs, but this can vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing.

3. The conclusion brings your essay to a close and is typically one paragraph long. It should summarize the main points of the essay and leave the reader with something to think about.

The length of your paragraphs can vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing. So, make sure you take the time to plan out your essay structure so each section flows smoothly into the next.

Introduction

When it comes to writing an essay, the introduction is a critical component that sets the tone for the entire piece. A well-crafted introduction not only grabs the reader’s attention but also provides them with a clear understanding of what the essay is all about. An essay editor can help you achieve this, but it’s best to know the brief yourself!

Let’s take a look at how to write an attractive and informative introductory paragraph.

1. Construct an attractive hook

To grab the reader’s attention, an opening statement or hook is crucial. This can be achieved by incorporating a surprising statistic, a shocking fact, or an interesting anecdote into the beginning of your piece.

For example, if you’re writing an essay about water conservation you can begin your essay with, “Clean drinking water, a fundamental human need, remains out of reach for more than one billion people worldwide. It deprives them of a basic human right and jeopardizes their health and wellbeing.”

2. Provide sufficient context or background information

An effective introduction should begin with a brief description or background of your topic. This will help provide context and set the stage for your discussion.

For example, if you’re writing an essay about climate change, you start by describing the current state of the planet and the impact that human activity is having on it.

3. Construct a well-rounded and comprehensive thesis statement

A good introduction should also include the main message or thesis statement of your essay. This is the central argument that you’ll be making throughout the piece. It should be clear, concise, and ideally placed toward the end of the introduction.

By including these elements in your introduction, you’ll be setting yourself up for success in the rest of your essay.

Let’s take a look at an example.

Essay introduction example

- Background information

- Thesis statement

The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane in 1903 revolutionized the way humans travel and explore the world. Prior to this invention, transportation relied on trains, boats, and cars, which limited the distance and speed of travel. However, the airplane made air travel a reality, allowing people to reach far-off destinations in mere hours. This breakthrough paved the way for modern-day air travel, transforming the world into a smaller, more connected place. In this essay, we will explore the impact of the Wright Brothers’ invention on modern-day travel, including the growth of the aviation industry, increased accessibility of air travel to the general public, and the economic and cultural benefits of air travel.

Body paragraphs

You can persuade your readers and make your thesis statement compelling by providing evidence, examples, and logical reasoning. To write a fool-proof and authoritative essay, you need to provide multiple well-structured, substantial arguments.

Let’s take a look at how this can be done:

1. Write a topic sentence for each paragraph

The beginning of each of your body paragraphs should contain the main arguments that you’d like to address. They should provide ground for your thesis statement and make it well-rounded. You can arrange these arguments in several formats depending on the type of essay you’re writing.

2. Provide the supporting information

The next point of your body paragraph should provide supporting information to back up your main argument. Depending on the type of essay, you can elaborate on your main argument with the help of relevant statistics, key information, examples, or even personal anecdotes.

3. Analyze the supporting information

After providing relevant details and supporting information, it is important to analyze it and link it back to your main argument.

4. Create a smooth transition to the next paragraph

End one body paragraph with a smooth transition to the next. There are many ways in which this can be done, but the most common way is to give a gist of your main argument along with the supporting information with transitory words such as “however” “in addition to” “therefore”.

Here’s an example of a body paragraph.

Essay body paragraph example

- Topic sentence

- Supporting information

- Analysis of the information

- Smooth transition to the next paragraph

The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane revolutionized air travel. They achieved the first-ever successful powered flight with the Wright Flyer in 1903, after years of conducting experiments and studying flight principles. Despite their first flight lasting only 12 seconds, it was a significant milestone that paved the way for modern aviation. The Wright Brothers’ success can be attributed to their systematic approach to problem-solving, which included numerous experiments with gliders, the development of a wind tunnel to test their designs, and meticulous analysis and recording of their results. Their dedication and ingenuity forever changed the way we travel, making modern aviation possible.

A powerful concluding statement separates a good essay from a brilliant one. To create a powerful conclusion, you need to start with a strong foundation.

Let’s take a look at how to construct an impactful concluding statement.

1. Restructure your thesis statement

To conclude your essay effectively, don’t just restate your thesis statement. Instead, use what you’ve learned throughout your essay and modify your thesis statement accordingly. This will help you create a conclusion that ties together all of the arguments you’ve presented.

2. Summarize the main points of your essay

The next point of your conclusion consists of a summary of the main arguments of your essay. It is crucial to effectively summarize the gist of your essay into one, well-structured paragraph.

3. Create a lasting impression with your concluding statement

Conclude your essay by including a key takeaway, or a powerful statement that creates a lasting impression on the reader. This can include the broader implications or consequences of your essay topic.

Here’s an example of a concluding paragraph.

Essay conclusion example

- Restated thesis statement

- Summary of the main points

- Broader implications of the thesis statement

The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane forever changed history by paving the way for modern aviation and countless aerospace advancements. Their persistence, innovation, and dedication to problem-solving led to the first successful powered flight in 1903, sparking a revolution in transportation that transformed the world. Today, air travel remains an integral part of our globalized society, highlighting the undeniable impact of the Wright Brothers’ contribution to human civilization.

Types of essays

Most essays are derived from the combination or variation of these four main types of essays . let’s take a closer look at these types.

1. Narrative essay

A narrative essay is a type of writing that involves telling a story, often based on personal experiences. It is a form of creative nonfiction that allows you to use storytelling techniques to convey a message or a theme.

2. Descriptive essay

A descriptive essay aims to provide an immersive experience for the reader by using sensory descriptors. Unlike a narrative essay, which tells a story, a descriptive essay has a narrower scope and focuses on one particular aspect of a story.

3. Argumentative essays

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that aims to persuade the reader to adopt a particular stance based on factual evidence and is one of the most common forms of college essays.

4. Expository essays

An expository essay is a common format used in school and college exams to assess your understanding of a specific topic. The purpose of an expository essay is to present and explore a topic thoroughly without taking any particular stance or expressing personal opinions.

While this article demonstrates what is an essay and describes its types, you may also have other doubts. As experts who provide essay editing and proofreading services , we’re here to help.

Our team has created a list of resources to clarify any doubts about writing essays. Keep reading to write engaging and well-organized essays!

- How to Write an Essay in 8 Simple Steps

- How to Write an Essay Header

- How to Write an Essay Outline

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between an argumentative and an expository essay, what is the difference between a narrative and a descriptive essay, what is an essay format, what is the meaning of essay, what is the purpose of writing an essay.

Found this article helpful?

Leave a Comment: Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Your vs. You’re: When to Use Your and You’re

Your organization needs a technical editor: here’s why, your guide to the best ebook readers in 2024, writing for the web: 7 expert tips for web content writing.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Get carefully curated resources about writing, editing, and publishing in the comfort of your inbox.

How to Copyright Your Book?

If you’ve thought about copyrighting your book, you’re on the right path.

© 2024 All rights reserved

- Terms of service

- Privacy policy

- Self Publishing Guide

- Pre-Publishing Steps

- Fiction Writing Tips

- Traditional Publishing

- Academic Writing and Publishing

- Partner with us

- Annual report

- Website content

- Marketing material

- Job Applicant

- Cover letter

- Resource Center

- Case studies

Academic Skills

- Academic Writing

- Essay Structure

- Essay Preparation

- Where to start

- Research strategies

- Critical Analysis

- Referencing

Your Academic Support Officer

If you have any questions about academic skills or would like some support, contact your Academic Support Officer:

Kevin Byrne

Structuring essays

On this page:

Once you've understood the assignment and prepared your argument, you need to decide how you're going to present your essay in a logical structure.

Use our quick guide to planning out an essay to help you decide where and what to include in you introduction, conclusion, and main body of your text.

Introduction

The introduction of your essay serves as a road map establishing the scope of the discussion and presenting the central argument that will be developed throughout the essay. This is a space to make a positive first impression of your argument, your writing style, and the overall quality of your work. It will provide a solid ground for your assignment - providing you do everything you say you will .

Plan of Action

Your introduction should outline how the main body of your writing will proceed. It will give the reader a general idea of the theme of your work, why you think it is important, and where you plan to detail all of your arguments and ideas. By the end of the introduction you should have formed an outline for a coherent structure that your reader can follow.

Definition of Terms

Use the introduction to define specific terms related to the essay question to demonstrate engagement and clarity. For example:

This essay will explore the concept of 'social media' as platforms that facilitate online interactions among users.

Breadth of Discussion

Show the range of viewpoints relevant to the essay question. For instance:

Social media's impact on mental health outcomes is multifaceted, encompassing economic, social, and psychological perspectives. This essay will focus on the social and psychological aspects, particularly examining...

The main body of the essay elaborates on the points introduced in the introduction and develops arguments supported by evidence. It should me structured in paragraphs, and each paragraph should follow a logical sequence that build up to your conclusion.

Self-contained Paragraphs

Each paragraph should focus on a specific point related to the main argument. Start with a clear topic sentence that relates directly to the thesis statement.

- Unified: All the sentences in a single paragraph should be related to a single idea (often expressed in the topic sentence of the paragraph).

- Clearly related to the thesis or question being asked: The sentences should all refer to the central idea, question or thesis, of the paper.

- Coherent: The sentences should be arranged logically and should follow a definite plan for development.

- Well-developed: Every idea discussed in the paragraph should be adequately explained and supported through evidence and details that work together to explain the paragraph's central theme.

Provide Evidence

Support your arguments with evidence such as data, examples, or scholarly sources. For example:

Studies have shown a correlation between excessive social media use and increased feelings of anxiety and depression (Smith, 2020).

Relate Back to the Thesis

Ensure that each paragraph explicitly connects back to the central argument or the essay question. This helps maintain a clear and focused argument.

It is helpful to check your essay plan, your introduction and the conclusion as you go along to make sure everything adds up.

The conclusion brings together the key points of the essay and restates the central argument in light of the evidence provided in the main body. This is your opportunity to synthesise your ideas into a coherent conclusion, summarise what you have written, and reiterate the thesis statement from your introduction.

Bring all your ideas together and address the question one final time in one concise paragraph. Here you will abridge what you have accomplished, (dis)proven, or demonstrated within your main body. It is your final chance to ensure that the reader has been provided evidence to establish the main point of the writing. It is also your final chance to explicitly illustrate how you have met the assignment brief.

Briefly summarise the main points discussed in the essay. Avoid introducing new information, but make sure to reference

Restate the thesis statement, emphasising its significance in light of the evidence presented in the main body. This will help you make sure you have kept on-topic and achieved your aim. For example:

In conclusion, this essay has demonstrated that social media can have significant impacts on mental health outcomes, particularly in relation to...

- << Previous: Academic Writing

- Next: Essay Preparation >>

- Last Updated: Sep 24, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://northlindsey.libguides.com/c.php?g=722379

This Reading Mama

Non-Fiction Text Features and Text Structure

*This post contains affiliate links. Please read my full disclosure policy for more information.

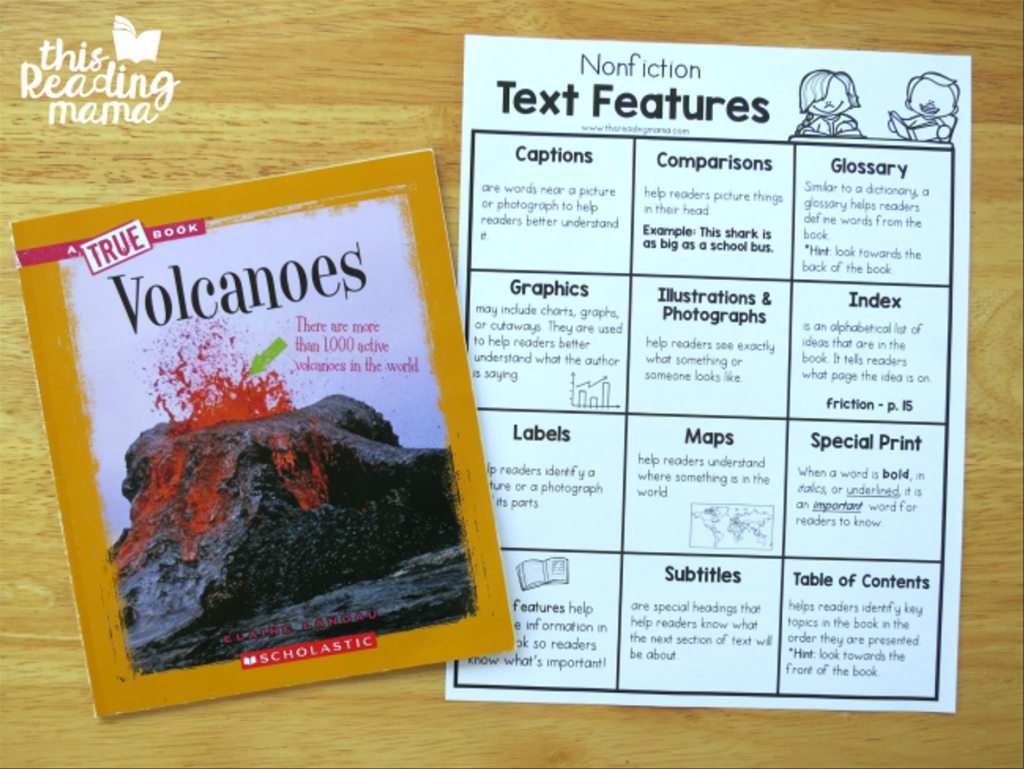

What are Text Features?

Text features are to non-fiction what story elements are to fiction. Text features help the reader make sense of what they are reading and are the building blocks for text structure (see below). So what exactly are non-fiction text features?

Text Features and Comprehension

Text features go hand-in-hand with comprehension. If the author wants a reader to understand where a country is in the world, then providing a map helps the reader visualize and understand the importance of that country’s location. If the anatomy of an animal is vitally important to understanding a text, a detailed photograph with labels gives the reader the support he needs to comprehend the text.

Text features also help readers determine what is important to the text and to them. Without a table of contents or an index, readers can spend wasted time flipping through the book to find the information they need. Special print helps draw the attention of the reader to important or key words and phrases.

In my experience, readers of all ages, especially struggling readers tend to skip over many of the text features provided within a text. To help readers understand their importance, take some time before reading to look through the photographs/illustrations, charts, graphs, or maps and talk about what you notice. Make some predictions about what they’ll learn or start a list of questions they have based off of the text features.

Sometimes, it’s even fun to make a point to those readers who like to skip over the text features by retyping the text with no features and asking them to read the text without them first. Once they do that, discuss how difficult comprehension was. Then, give them the original text and help them to see the difference it makes in understanding.

Find our free Nonfiction Text Features Chart !

Some Common Text Features within Non-Fiction

- Captions: Help you better understand a picture or photograph

- Comparisons: These sentences help you to picture something {Example: A whale shark is a little bit bigger than a school bus.}

- Glossary: Helps you define words that are in the book

- Graphics: Charts, graphs, or cutaways are used to help you understand what the author is trying to tell you

- Illustrations/Photographs: Help you to know exactly what something looks like

- Index: This is an alphabetical list of ideas that are in the book. It tells you what page the idea is on.

- Labels: These help you identify a picture or a photograph and its parts

- Maps: help you to understand where places are in the world

- Special Print: When a word is bold , in italics , or underlined , it is an important word for you to know

- Subtitles: These headings help you to know what the next section will be about

- Table of Contents: Helps you identify key topics in the book in the order they are presented

What is Text Structure?

Simply put, text structure is how the author organizes the information within the text.

Why do text structures matter to readers?

- When readers what kind of structure to expect, it helps them connect to and remember what they’ve read better.

- It gives readers clues as to what is most important in the text.

- It helps readers summarize the text. For example, if we’re summarizing a text that has a sequence/time order structure, we want to make sure we summarize in the same structure. (It wouldn’t make sense to tell an autobiography out of order.)

Examples of Non-Fiction Text Structure

While there are differences of opinion on the exact amount and names of different kinds of text structure, these are the 5 main ones I teach.

You can read more about each one on day 3 and day 4 of our Teaching Text Structure to Readers series .

1. Problem/Solution

The author will introduce a problem and tell us how the problem could be fixed. There may be one solution to fix the problem or several different solutions mentioned. Real life example : Advertisements in magazines for products (problem-pain; solution-Tylenol)

2. Cause and Effect

The author describes something that has happened which has had an effect on or caused something else to happen. It could be a good effect or a bad effect. There may be more than one cause and there may also be more than one effect. (Many times, problem/solution and cause and effect seem like “cousins” because they can be together.) Real life example : A newspaper article about a volcano eruption which had an effect on tourism

3. Compare/Contrast

The author’s purpose is to tell you how two things are the same and how they are different by comparing them. Real life example : A bargain hunter writing on her blog about buying store-brand items and how it compares with buying name-brand items.

4. Description/List

Although this is a very common text structure, I think it’s one of the trickiest because the author throws a lot of information at the reader (or lists facts) about a certain subject. It’s up to the reader to determine what he thinks is important and sometimes even interesting enough to remember. Real life example : A soccer coach’s letter describing to parents exactly what kind of cleats to buy for their kids.

5. Time Order/Sequence

Texts are written in an order or timeline format. Real life examples : recipes, directions, events in history

Note: Sometimes the text structure isn’t so easy to distinguish. For example, the structure of the text as a whole may be Description/List (maybe about Crocodilians), but the author may devote a chapter to Compare/Contrast (Alligators vs. Crocodiles). We must be explicit about this with students.

More Text Structure Resources:

- 5 Days of Teaching Text Structure to Readers {contains FREE printable packs for Fiction AND Non-fiction, as seen above}

- Fiction Story Elements and Text Structure

- Teaching Kids How to Retell with Fiction (Fiction Text Structure)

- Teaching Kids How to Summarize

- Our Favorite Nonfiction Series Books , perfect companions for working on text features/structures!

Enjoy teaching! ~Becky

The Structure of Non-Fiction Texts

Understanding the structure of non-fiction texts involves analysing how writers organise information, ideas, and arguments to effectively convey their message. Here's Revision World’s comprehensive guide to help you revise structure in non-fiction texts, along with examples:

Introduction:

Introduces the topic and sets the tone for the rest of the text.

Example: In an opinion article about climate change, the introduction might begin with a startling statistic or a thought-provoking question to grab the reader's attention.

This states the central argument or purpose of the text.

Example: In an argumentative essay on the importance of exercise, the main statement might be: "Regular physical activity is essential for maintaining physical health and mental well-being."

Body Paragraphs:

Present supporting evidence, examples, and arguments to develop the main idea.

Example: Each body paragraph in a persuasive speech about animal rights might focus on a specific aspect of the topic, such as cruelty in factory farming or the environmental impact of animal agriculture.

Transitions:

Connect ideas and paragraphs smoothly, ensuring coherence and logical progression.

Example: Transitional phrases like "furthermore," "in addition," and "however" signal shifts between different points or perspectives in an argumentative essay.

Counterarguments and Rebuttals:

Address opposing viewpoints to strengthen the argument.

Example: In a debate script about the benefits of renewable energy, the writer might anticipate and refute common objections, such as concerns about the reliability of solar power.

Conclusion:

Summarises key points and restates the main theme, leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

Example: In a documentary exploring the impacts of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems, the conclusion might encourage viewers to adopt eco-friendly practices such as reducing single-use plastic consumption and supporting organisations dedicated to ocean conservation.

Chronological Order:

Presents events or information in the order they occurred.

Example: A biography of Nelson Mandela might follow his life chronologically, from his childhood to his time in prison to his presidency of South Africa.

Cause and Effect:

Explores the relationship between events, actions, or phenomena and their consequences.

Example: In a journalistic investigation into the root causes and consequences of rising crime rates in urban areas, the article may explore factors such as socioeconomic inequality, lack of access to education and employment opportunities, and ineffective law enforcement strategies. It would then discuss the resulting impacts on communities, including increased rates of violence, property crime, and strained police resources.

Problem-Solution:

Identifies a problem or issue and proposes solutions or strategies for resolution.

Example: A policy brief on homelessness might outline the root causes of homelessness and recommend interventions such as affordable housing initiatives and support services for at-risk populations.

Comparison and Contrast:

Examines similarities and differences between two or more subjects or ideas.

Example: In a blog post comparing the benefits and drawbacks of electric cars versus traditional petrol or diesel powered vehicles, the writer may discuss factors such as environmental impact, cost of ownership, driving range, and availability of charging infrastructure. By highlighting both the advantages and limitations of each type of vehicle, readers can make informed decisions when considering their next car purchase.

Understanding the structure of non-fiction texts helps readers follow the flow of ideas and arguments, aiding comprehension and critical analysis. By identifying the components of structure and their functions, you can better appreciate how writers organise their writing to effectively communicate with their audience.

Reading Skills

Analyzing the text structure of non-fiction texts.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: June 26, 2023

Introduction

Exploring the world of non-fiction is like embarking on an exciting treasure hunt. Each piece of non-fiction literature presents a wealth of knowledge and perspectives to uncover. A crucial tool on this quest? Understanding non-fiction text structure. Grasping this concept can transform your reading experience, providing you a map to navigate the text’s content more efficiently.

What is Text Structure?

Text structure is how an author sets up what they’re writing. Think of it like a builder using a plan to make a house. An author uses a certain structure to share their thoughts in a clear way. This could be telling events in order they happened for a history story, showing a cause and then its effect for a science paper, laying out a problem and then its solution for a persuasive article, or looking at similarities and differences in a critical review.

Authors use these structures to make their text make sense and guide their readers. Knowing the text structure helps readers guess what comes next, understand complex ideas, and connect better with the text. It’s like a hidden support that keeps a text together and gives it its aim and meaning.

Why Should Readers Analyze Text Structure?

Analyzing text structure is like looking under the hood of a car; it shows us how things work and lets us see the hard work that goes into making it. When we look into how a text is structured, we get a chance to understand how the author thinks and how they built their story or argument. This doesn’t just help us understand the text better; it also improves our ability to think critically and relate to others

By spotting patterns, picking out main ideas, and getting the flow of thoughts, readers can feel more connected to the text, making reading more enjoyable. Plus, analyzing text structure helps readers have good conversations, write better essays, and, in a bigger sense, be more critical when they take in information. So, looking at text structure gives readers useful skills that they can use not just in school, but also in their daily life.

Common Text Structures

Understanding non-fiction texts involves recognizing their underlying structure. Let’s explore five of the most common text structures found in non-fiction:

- Cause and Effect

- Problem and Solution

- Description

- Compare and Contrast

Cause and Effect Text Structure

This kind of text shows how one thing leads to another. The cause is why something happened, and the effect is what happened as a result. You might see this in science or history books. These books carefully link an action or event (the cause) with what changed or happened afterward (the effect). Spotting this structure helps you understand the reason behind different events and processes.

Problem- Solution Text Structure

Texts using the problem-solution structure talk about a problem, then suggest ways to solve it. You’ll see this a lot in work about social, political, or environmental problems. These texts discuss a problem and then suggest possible ways to fix it. Knowing this structure lets you think critically about the suggested solutions to different problems

Sequence Text Structure

The sequence structure puts information in a certain order, often the order things happened. This structure is used a lot in history books, biographies, how-to guides, or instructions. It gives readers a step-by-step rundown or timeline of events. Spotting this structure can help you follow the chain of events or steps accurately.

Description Text Structure

Texts with a description structure give lots of information about a topic, often using words that paint a picture for the reader. These texts can be about anything from scientific ideas to historical events. They dive into the details to give readers a full understanding of the subject. Knowing this structure helps you visualize and understand complex ideas.

Compare and Contrast Text Structure

This structure analyzes the similarities and differences between two or more topics. It’s used to provide nuanced perspectives on multiple subjects. Non-fiction authors often use this structure to compare different theories, concepts, events, or entities. Understanding this structure can help you see different perspectives and make informed comparisons.

How to Analyze the Structure of Non-Fiction Texts

Now that you’ve learned about the different types of text structures, it’s important to understand how to determine the structure of a particular text. Analyzing the structure of non-fiction texts involves a few important steps.

Step 1 : Begin with an open mind and read through the text. Try to understand the big picture without focusing too much on little details.

Step 2 : Pay attention to how the author shares information. Are events told in the order they happened? Does the author talk about a problem and then suggest a solution? Or maybe the text gives a lot of information about one subject? Spotting these patterns will help you figure out the text’s structure.

Step 3: Try to think about why the author picked this structure. How does it help get the main ideas and themes across? How does it change how you understand the text as a reader?

Step 4: Link the text structure to the author’s goal or point of view. Ask yourself, “How does this structure support what the author is trying to say or do?”

By following these steps, you’ll get a deeper understanding of the text, which will help you understand what you’re reading and think critically about it. If you do this often, you’ll become a stronger, more analytical reader.

How Text Structure Contributes to the Author’s Purpose

A non-fiction author’s purpose or point of view can shape their text structures. For instance, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is a complex piece of non-fiction writing that integrates various text structures, as it addresses different aspects of the civil rights struggle. King’s purpose is shaped by the use of two primary text structures: problem-solution and cause and effect.

- Problem-Solution: Throughout the letter, King identifies various problems related to racial injustice and segregation. For instance, he discusses the problem of unjust laws and racial discrimination. He then proposes nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience as solutions to these problems.

- Cause and Effect: King also uses the cause and effect structure to demonstrate the relationship between racial discrimination (cause) and the resulting civil unrest and protest (effect). He explains how systemic oppression leads to nonviolent resistance and protests, emphasizing that these actions are the effects of ongoing racial prejudice and inequality.

Understanding the structure of non-fiction texts allows you to appreciate these nuances and gain a more profound insight into the author’s message. Just like each author’s personal background and purpose shape a novel, these factors influence the structure and presentation of non-fiction works, making each one a unique contribution to our collective knowledge.

Text Structure Practice: Analyzing George Bush’s 9/11 Speech

Let’s use what we know about text structures to look at George W. Bush’s speech after the 9/11 attacks.

Read through the speech carefully. While you read, underline or mark important points and transitions.

Think about possible text structures. Think about whether ‘Cause and Effect’ or ‘Chronological’ structures might apply. In ‘Cause and Effect’, we would expect the text to talk about a cause (like the terrorist attacks) and then focus on what happened because of it. In a ‘Chronological’ structure, the speech would mostly be organized by time. However, while there are pieces of these structures, the speech doesn’t mainly follow them.

Confirm the text structure. Based on what you’ve looked at, figure out the main text structure. In this case, the speech’s focus on a problem (the attacks) and the suggested solution (actions for safety and unity) fits the ‘Problem and Solution’ structure.

Spot the ‘Problem’. In Bush’s speech, this is the 9/11 attacks. Pay attention to how he talks about the events and how they’ve affected the country. For example, the quote “Today, our fellow citizens, our way of life, our very freedom came under attack in a series of deliberate and deadly terrorist acts.” identifies the problem.

Look for the ‘Solution’. Bush talks about this when he shares the steps being taken for the country’s safety and his call for unity and strength. A good example of this is in the line: “We go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.” This is where Bush is discussing bringing the country together, promoting unity, and encouraging strength.

By following these steps, you can dissect the ‘Problem and Solution’ structure of Bush’s speech. This approach will help you understand the speech’s purpose, see how it was designed to reassure a shocked nation, and grasp how the speaker encouraged unity and resilience in a time of crisis. Applying these steps to other non-fiction texts will enhance your comprehension and analytical skills, revealing deeper layers of understanding.

In this digital age, understanding how to analyze and comprehend non-fiction text structures is a crucial skill for students. By recognizing and understanding structures like Cause and Effect, Problem- Solution, Sequence, Description, and Compare and Contrast, you can unlock a deeper understanding of the texts you encounter.

Whether it’s a novel by a renowned author, an informative article, or a powerful speech like George W. Bush’s 9/11 address, recognizing these structures will empower you to grasp an author’s purpose, viewpoint, and strategy more fully.

Practice Makes Perfect

By analyzing non-fiction texts, you not only develop your reading comprehension skills but also gain a deeper understanding of the underlying ideas and themes. However, just like any skill, effective analysis of text structure requires regular practice.

Here at Albert, we offer engaging and comprehensive resources to help you perfect this skill. Our practice questions and reading exercises are specifically designed to hone your understanding of different non-fiction text structures.

For more practice with this essential skill, check out our Text Structure Practice Questions in our Short Readings course , designed to provide thorough, step-by-step practice. Readers at all ability levels may enjoy our Leveled Readings course, which offers Lexile® leveled passages focused on a unifying essential question that keeps all students on the same page regardless of reading level. Learn more about the Lexile Framework here !

So, keep practicing, keep breaking down texts, and keep working on this important skill. Remember, every new text you read is a chance to get even better at analyzing.

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

AQA GCSE English Language

Understanding structure in non-fiction texts, recognising organisation and layout.

Non-fiction texts come in various forms, each with its own typical structure. For example, essays often follow a clear introduction-body-conclusion structure, while reports may be divided into sections with headings and subheadings. Articles might start with a lead paragraph that summarises the main points, followed by supporting paragraphs.

As you read, note the layout of the text. How is it organised? What sections can you identify?

Understanding Text Features

Non-fiction texts often include features like headings, subheadings, bullet points, captions and diagrams. These features serve specific purposes, such as organising information, emphasising key points or providing additional information.

- Headings and Subheadings – These are used to organise information into manageable sections. They give a snapshot of what the following section is about, helping you to navigate the text.

- Bullet Points – These are used to list information in a clear, concise manner. They’re often used to summarise points, list steps in a process or highlight key pieces of information.

- Captions – These are short descriptions that accompany pictures, diagrams or graphs. They help explain what the visual element is showing and how it relates to the text.

- Diagrams – These are visual representations of information. They can help explain complex ideas or processes in a simple, visual way.

Identifying the Argument or Main Point

In non-fiction, the author’s main argument or point is the central idea they want to communicate to their readers. This could be an opinion, a fact, a discovery or a perspective. It’s the ‘why’ behind the text – why the author felt it necessary to write this piece. The main argument or point is usually stated clearly in the introduction and then developed throughout the text.

For example, in A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, the main point is to explain complex concepts in cosmology to a general audience. This point is developed through detailed explanations and examples.

Try to summarise the main argument or point in one sentence. Then, identify how this point is developed throughout the text.

Analysing the Structure’s Contribution

The structure of a non-fiction text can contribute to its clarity, persuasiveness or impact. A well-structured text will present information in a logical and coherent way, making it easier for readers to understand and engage with the content.

Consider how the structure of the text affects your understanding. Does it make the argument clearer? Does it make the text more persuasive or impactful?

You’ve used 3 of your 10 free revision notes for the month

Sign up to get unlimited access to revision notes, quizzes, audio lessons and more.

Last updated: April 27th, 2024

Please read these terms and conditions carefully before using our services.

Definitions

For these Terms and Conditions:

- Affiliate means an entity that controls, is controlled by or is under common control with a party, where “control” means ownership of 50% or more of the shares, equity interest or other securities entitled to vote for the election of directors or other managing authority.

- Account means a unique account created for you to access our services or some of our services.

- Country refers to the United Kingdom

- Company refers to Shalom Education Ltd, 86 London Road, (Kingsland Church), Colchester, Essex, CO3 9DW, and may be referred to as ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’, or ‘Shalom Education’ in this agreement.

- Device means any device that can access the Service, such as a computer, a mobile phone or a digital tablet.

- Feedback means feedback, innovations or suggestions sent by You regarding the attributes, performance or features of our service.

- Free Trial refers to a limited period of time that may be free when purchasing a subscription.

- Orders mean a request by you to purchase services or resources from us.

- Promotions refer to contests, sweepstakes or other promotions offered by us through our website or official social media platforms.

- Services refer to our website, resources and tutoring service.

- Subscriptions refer to the services or access to the service offered on a subscription basis by the company to you.

- Terms and Conditions (also referred to as “Terms”) mean these Terms and Conditions that form the entire agreement between you and Shalom Education Ltd regarding the use of the services we offer.

- Third-party Social Media Service means any services or content (including data, information, products or services) provided by a third party that may be displayed, included or made available on the website.

- Website refers to Shalom-education.com, accessible from https://www.shalom-education.com

- You means the individual accessing or using our services, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using our services.

- Tutor refers to an individual that teaches a single pupil or a small group of students which have registered with Shalom Education Ltd.

- Tutee refers to a student or a pupil that has registered for tutoring with Shalom Education Ltd, which is administered through our tutoring platform.

Acknowledgement

Thank you for choosing Shalom Education Tuition for your educational needs. These terms and conditions outline the rules and regulations for the use of our services, and the agreement that will govern your relationship with us.

By accessing or using our services, you accept and agree to be bound by these terms and conditions, and our privacy policy , which describes our policies and procedures for the collection, use, and disclosure of your personal information when you use our website.

It is important that you read both documents carefully before using our services, as they outline your rights and obligations as a user of our services. If you do not agree to these terms and conditions or our privacy policy, please do not use our services. We hope you have a positive and educational experience with Shalom Education Tuition.

Signing up for Tutoring or Membership Accounts

By signing up for tutoring or membership accounts through the website, you confirm that you have the legal ability to enter into a binding contract.

Your information

When you place an order, we may ask you to provide certain information, such as your name, email, phone number, credit card details and billing address.

You confirm that you have the right to use the payment method you choose, and that the information you provide is accurate and complete. By submitting your information, you give us permission to share it with payment processing third parties to complete your order.

Order cancellation

We reserve the right to cancel your order at any time for various reasons, including but not limited to:

- Unavailability of services (e.g. no tutors available)

- Errors in the description or prices of services

- Errors in your order

- Suspected fraud or illegal activity

Cancelling your order

Any services that you purchase can only be returned in accordance with these terms and conditions. Our Returns Policy forms a part of these Terms and Conditions.

In general, you have the right to cancel your order and receive a full refund within 14 days of placing it. However, you cannot cancel an order for services that are made to your specifications or are clearly personalised, or for services that you have already received in part.

Money-Back Guarantee: If you are not satisfied with the quality of your tutoring session, you may be eligible for a full or partial refund or credit. To request a refund or credit, please contact us within 24 hours after the end of the session and provide a detailed explanation of your dissatisfaction. We will review your request and, if approved, will issue a refund or credit to your account.

- Please note that refunds or credits may not be available for all types of tutoring services and may be subject to fees or other charges. For more information, please contact us.

Errors and inaccuracies

We strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information about the service we offer, but we cannot guarantee that everything will be completely accurate and up-to-date at all times. Prices, product images, descriptions, availability, and services may be inaccurate, incomplete, or out of date.

We reserve the right to change or update any information, and to correct errors, inaccuracies, or omissions at any time without prior notice.

Prices policy

We reserve the right to change our prices at any time before accepting your order.

All tutoring services and membership accounts purchased on our website must be paid for in full at the time of purchase, for the required time of use. We accept a variety of payment methods, including credit cards, debit cards, and online payment services like PayPal.

Your payment card may be subject to validation checks and authorisation by your card issuer. If we do not receive the necessary authorisation, we cannot be held responsible for any delays or failure to deliver your order.

Subscriptions

Subscription period.

Our tutoring services are available with a pay-as-you-go option or a subscription option that is billed on a monthly or annual basis. The tutoring account subscription will end at the end of the period. You can choose the subscription option that best suits your needs and cancel at any time.

Our membership accounts are billed monthly or annually and do not automatically renew after the period. You can choose to renew your membership account at the end of the period if you wish to continue your membership.

Subscription cancellations (tutoring services)

You can cancel your tutoring subscription renewal by contacting us at [email protected].

You can cancel your learning resources subscription renewal through your account settings or by contacting us at [email protected].

Please note that you will not receive a refund for fees you have already paid for your current subscription period, and you will be able to access the service until the end of your current subscription period.

We need accurate and complete billing information from you, including your full name, address, postal code, telephone number, and a valid payment method. If automatic billing fails, you will not receive tutoring services until a payment is made. If payment is not made within a reasonable time period, your account may be terminated.

Fee changes

We reserve the right to modify the subscription fees at any time. Any change in fees will take effect at the end of your current subscription period.

We will give you reasonable notice of any fee changes so you have the opportunity to cancel your subscription before the changes take effect. If you continue to use the service after the fee change, you agree to pay the modified amount.

In general, paid subscription fees are non-refundable. However, we may consider certain refund requests on a case-by-case basis and grant them at our discretion.

We may offer free trials of our subscriptions at our discretion. You may be asked to provide billing information to sign up for a free trial. If you do provide billing information, you will not be charged until the free trial period ends.

On the last day of the free trial, unless you have cancelled your subscription, you will be automatically charged the applicable subscription fees for the plan you have chosen. We reserve the right to modify or cancel free trial offers at any time without notice.

From time to time, we may offer promotions through the Service, such as discounts, special offers, or contests. These promotions may be governed by separate rules and regulations.

If you choose to participate in a promotion, please review the applicable rules and our privacy policy carefully. In the event of a conflict between the promotion rules and these terms and conditions, the promotion rules will take precedence.

Please note that any promotion may be modified or discontinued at any time, and we reserve the right to disqualify any participant who violates the rules or engages in fraudulent or dishonest behaviour. By participating in a promotion, you agree to be bound by the applicable rules and our decisions, which are final and binding in all matters related to the promotion.

User Accounts

In order to access certain features of our services, you may be required to create an account. When you create an account, you agree to provide accurate, complete, and current information about yourself as prompted by the account registration process. If you provide any false, inaccurate, outdated, or incomplete information, or if we have reasonable grounds to suspect that you have done so, we reserve the right to suspend or terminate your account.

You are solely responsible for maintaining the confidentiality of your account and password, and you agree to accept responsibility for all activities that occur under your account. If you believe that your account has been compromised or that there has been any unauthorised access to it, you must notify us immediately.