- Program Design

- Peer Mentors

- Excelling in Graduate School

- Oral Communication

- Written communication

- About Climb

Creating a 10-15 Minute Scientific Presentation

In the course of your career as a scientist, you will be asked to give brief presentations -- to colleagues, lab groups, and in other venues. We have put together a series of short videos to help you organize and deliver a crisp 10-15 minute scientific presentation.

First is a two part set of videos that walks you through organizing a presentation.

Part 1 - Creating an Introduction for a 10-15 Minute Scientfic Presentation

Part 2 - Creating the Body of a 10-15 Minute Presentation: Design/Methods; Data Results, Conclusions

Two additional videos should prove useful:

Designing PowerPoint Slides for a Scientific Presentation walks you through the key principles in designing powerful, easy to read slides.

Delivering a Presentation provides tips and approaches to help you put your best foot forward when you stand up in front of a group.

Other resources include:

Quick Links

Northwestern bioscience programs.

- Biomedical Engineering (BME)

- Chemical and Biological Engineering (ChBE)

- Driskill Graduate Program in the Life Sciences (DGP)

- Interdepartmental Biological Sciences (IBiS)

- Northwestern University Interdepartmental Neuroscience (NUIN)

- Campus Emergency Information

- Contact Northwestern University

- Report an Accessibility Issue

- University Policies

- Northwestern Home

- Northwestern Calendar: PlanIt Purple

- Northwestern Search

Chicago: 420 East Superior Street, Rubloff 6-644, Chicago, IL 60611 312-503-8286

Peer Recognized

Make a name in academia

Research conference presentation slide template + 3 design tips

Imagine this: research conference organizers send the participants a PowerPoint presentation slide template along with instructions that sound something like this:

Your presentation should be 20 minutes long; please keep the number of presentation slides to a maximum of 20.

A scientist who has 35 PowerPoint slides from the previous conference and might think:

OK, no problem! I will simply squeeze the information from the remaining fifteen slides into the first twenty to fit the provided presentation template.

The resulting presentation slides probably look similar to the figure below.

The scientist arrives at the conference, delivers the presentation, and receives applause at the end. He puts a picture from the conference on a social network and receives a comment: Sorry, I missed your presentation. Please email me the slides.

Ahh, he thinks , it’s a good thing I jammed that extra information into the presentation slides. Otherwise, it would be difficult for the person asking to get the full overview of my work!

It seems everyone is happy. The conference organizers got their 20 slides, the presenter successfully delivered his speech, and even the person on social media got the information she requested. But one thing is missing from the story – what about the people who actually showed up for the presentation?

The listeners were probably bewildered by the PowerPoint slides resembling an explosion of a hard drive disc over the screen. Their eyes were darting to follow the laser pointer from a figure in one corner of the slide to bullet points in the other. At around the third slide, many probably started daydreaming about the appetizers they can expect during the coffee break. They energetically clapped their hands at the end of the presentation because it was finally over. They forgot the performance as soon as the next speaker took the stage.

OK, but what about the person that asked you to send her the slides? Surely she would be disappointed when receiving a presentation which she cannot understand without you being there to present it. Well, send her the research paper (see my book to learn writing an impactful research paper). This is the piece of work that is meant for sharing and has to be self-explanatory. You are on the stage for a reason! Research conference presentation slides do not have to be self-explanatory.

In this post, you will learn three crucial tips for preparing scientific conference presentation slides to efficiently explain your research.

Tip No.1: One thought per slide

Presenters often use slides to keep the talk on track. Frequently this takes the form of the dreaded bullet-point list. Such an approach is a bad idea. Despite what some people claim, humans can not multitask at things that require deliberate thinking. Too much text will draw the listener’s attention away from what you are saying and toward reading the text on the slide. Since we read faster than we can speak, your listeners will already know what you are going to say, thus losing their attention.

The best approach for keeping the presentation slides light is to limit yourself to one single thought per slide. This could be, for example, a figure and several supporting bullet points taking up not more than one row each. But do not be afraid only to have one item, like a diagram, on the slide which takes only ten seconds to explain. There is no invisible jar that will start to spill over if you pour too many slides inside. A single thought per slide will allow the audience to better follow the presentation. This will also allow you to increase the size of text and images, thus ensuring that people in the back row can follow the talk.

Instead of using presentation slides as a teleprompter, use this valuable real estate for information that adds to your presentation, not duplicates it.

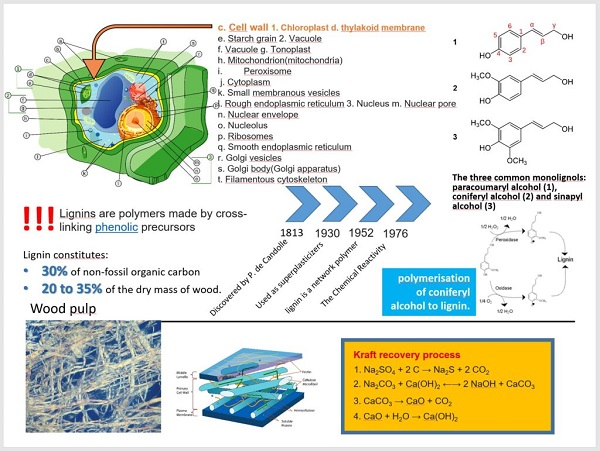

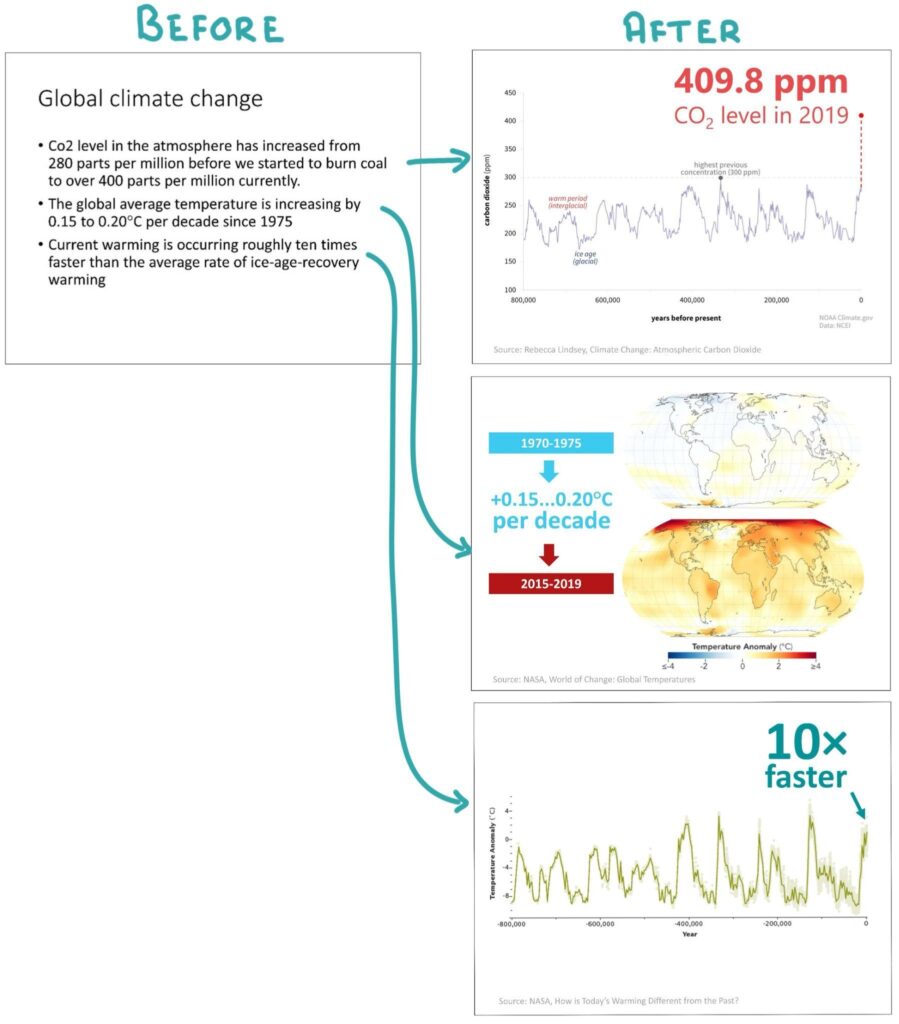

The “before” figure below presents a typical academic conference PowerPint presentation slide with three bullet points. I transformed it into three separate slides, each introducing one single thought. When displaying the “after” slides, the presenter would simply say out loud the information that was previously written.

You will notice that each of the converted slides uses visual information instead of text. Visuals draw human attention and can do a great job explaining things that would be difficult to put into words. Data charts, scientific illustrations, diagrams, or videos can all add another dimension to complement your presentation.

I am not claiming that you should strip your presentation slides of useful information or dumb them down. My reasoning stems from the vast majority of presentation slides that I have seen in research conferences. The slides are often overwhelmed with details that do more to confuse the listener than help. Focusing the slide content on visual information will help to support instead of distracting from your message. This brings us to the next topic.

Tip No.2: Presentation slides are for visual information

Even though I urge you to simplify the slides, it is clear that as a researcher, you will need to present complex information. This will most often take the form of different charts and illustrations (let’s call them graphics).

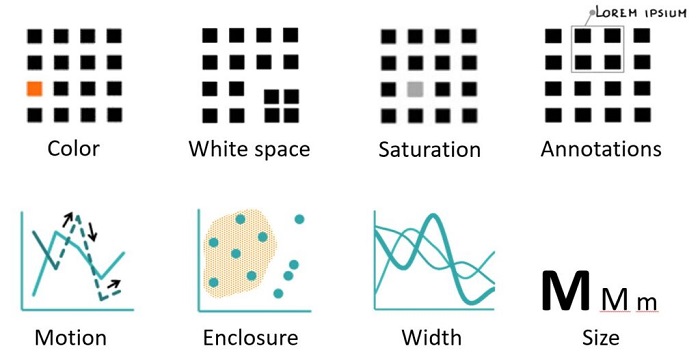

There is a lot to learn about the creation of graphics, but one element from the toolkit of designing graphics is particularly important for creating great scientific conference presentation slides. That is knowing how to guide the listeners’ attention. To do it, we must tap into a basic human instinct – people are drawn to outliers. Back at the dawn of homo-sapiens, this helped us spot danger or notice prey: think of a lion moving in a steppe – it is easy to imagine why our vision has evolved to pay attention to it.

Today we can take advantage of the 300 thousand-year-old instincts of our species to explain the all-important differences between two lines in a graph. Color, size, motion, white space, enclosure, and shape are some graphical features that can attract attention to particular elements in a chart.

Learn creating charts that tell a story

Knowing how to prepare efficient data charts and graphics will not only help you to create better slides; you will be able to use these skills to write clearer research papers and certainly it will increase your chances of obtaining research grants. My book Research Data Visualization and Scientific Graphics is a short guide that will help you to learn create charts that tell a story.

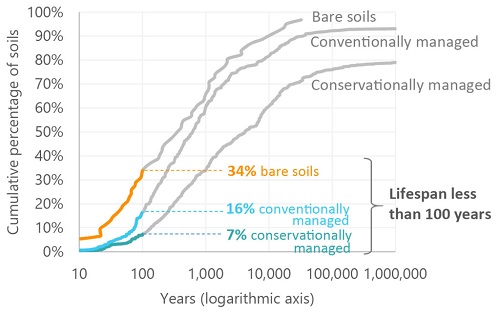

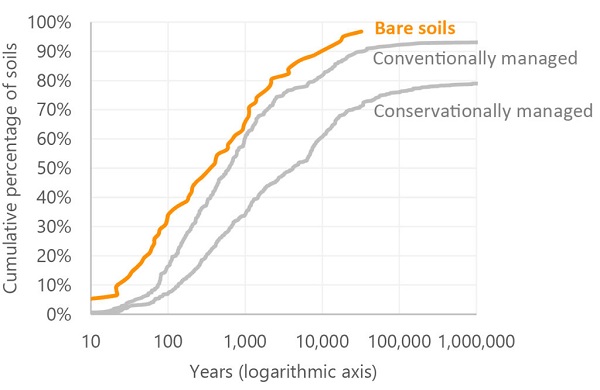

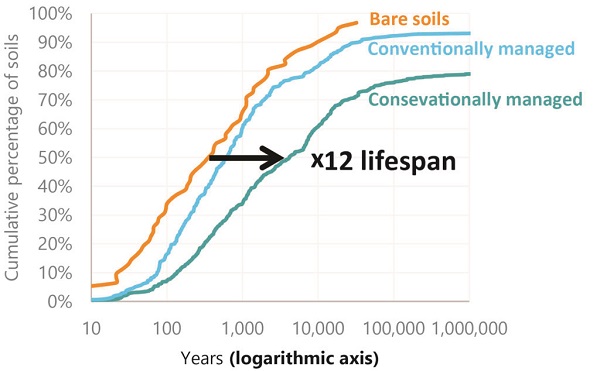

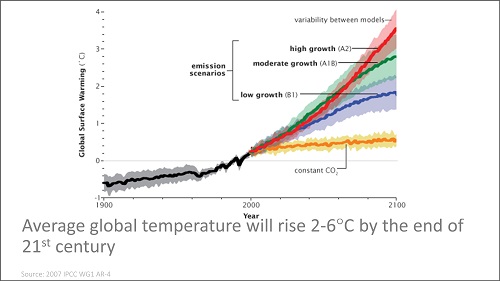

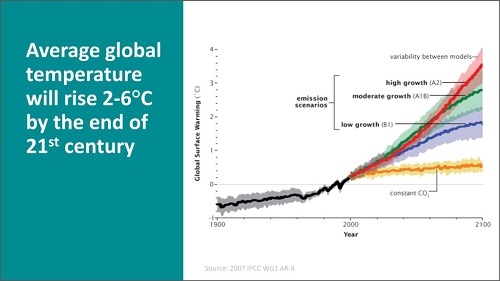

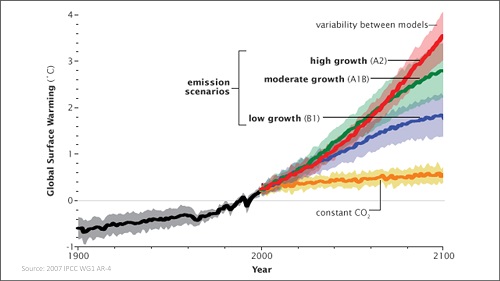

The example below directs the attention of the viewers within a single chart to the different topics that are being discussed (data from Evans et al. ). These could be presented in sequential slides.

The “Only 60 harvests ” left claims are exaggerated. Research by Evans et al. shows that depending on the soil management, only 7-34% of soils have less than 100 year lifespan.

Even most bare soils survive upwards of 300 years.

A good management practice can extend the soil’s life by several orders of magnitude.

A word of caution for those who might become too trigger-happy when discovering how easy it is to add animations to PowerPoint presentation slides: use these effects only when they add information to the story that you are telling. It quickly becomes irritating to see flying text, rotating slide transitions, expanding bullet points, and dissolving pictures. Revealing only one item at a time can be similarly annoying when done without a purpose.

Hint: Avoid using PowerPoint templates with busy backgrounds or colorful university logos on each slide. This limits your ability to draw the listeners’ attention to a particular item on the slide. On a busy background, the highlighted parts will not pop out quite as much as they would from a simple background.

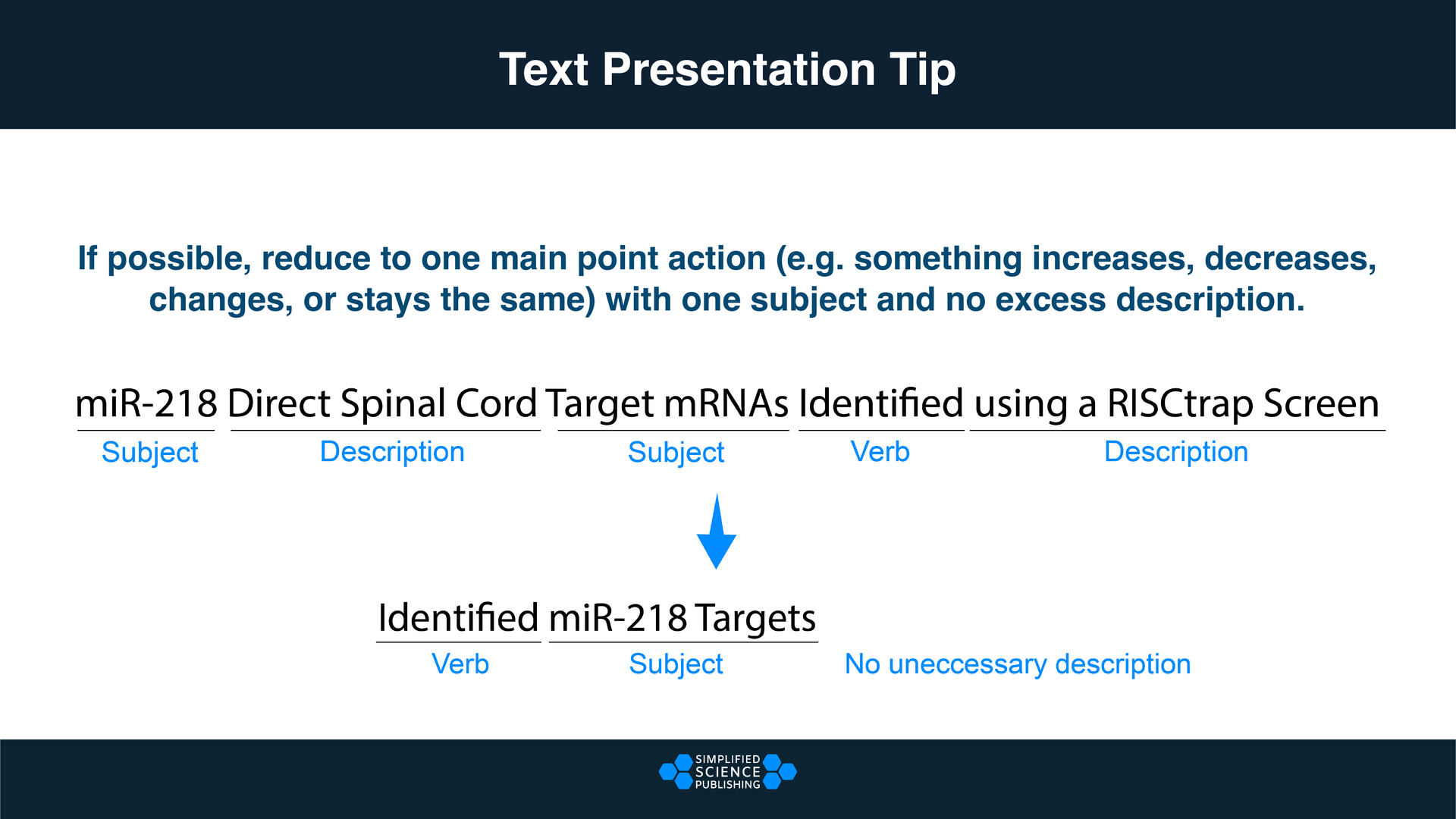

Tip No.3: Use action titles

Instinctively we can probably agree that the most important information, regardless of the type of medium, should be the largest. For example, it would be weird if the largest letters on a milk bottle would rea “Recyclable”. Interestingly, almost none of us actually follow this logic when designing scientific conference presentation slides.

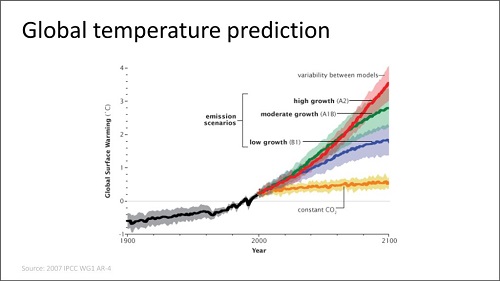

If you open PowerPoint, by default the largest text is the slide title. Since it is also located at the top of the slide, the title is going to be the first thing that draws the listener’s attention. But what do we put up there? Redundant, meaningless phrases like Methodology or Results of XYZ test . The figure below provides one such example.

The traditional PowerPoint title attracts all the attention while providing very little information.

You will probably agree that the tile Global temperature prediction does little to reveal what’s important about the information in the presentation slide. That is unless the listener has suddenly awoken from a nap and wants to understand what is the topic you are currently discussing. If this is the case, slide titles are the least of your problems.

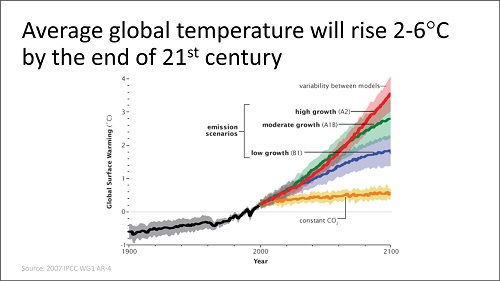

Instead of wasting the title for redundant information, a much better idea is to follow the advice from the C.N.Knaflic’s book Storytelling with Data in using an action title . An action title should provide information about the results, highlight an important observation or a conclusion for the particular slide. For example, instead of a whole block of slides having the title Results , the individual slide titles would say Observations have high variability or Simulation supports the test results .

In other words, a conference slide title should present something important about the research that the audience should not miss. It sets the expectations for what to expect from the information on the slide.

See below the different ways in which an action title can be displayed in the presentation slides. Doesn’t this approach offer more information than the traditional PowerPoint slide title that we saw earlier?

An action title highlights the key information that the listeners should not miss

Placing the action title at the bottom (and graying it out) is another option, giving more emphasis to the slide content.

The widescreen (16:9) slide size can be put to good use by dividing it into two columns: one for visual information, the other for key text.

Removing the title altogether allows increasing the size of the graphics. The presenter tells all the information that was previously written in the slide title.

Font size rule of thumb : Make sure that the listeners in the back rows can read your slides comfortably. Since you will rarely have the chance to test this, apply the rule of thumb by using 14 to 28 pt. font size for the main text and in charts. References and other background information could be smaller and grayed out to avoid distracting from the main content.

A free scientific conference presentation slide template

Now that we have reviewed three key principles of academic conference presentation slide design, use them to prepare your own slides. An even better way is to prepare a PowerPoint slide template that automatically incorporates many of these tips.

Below you will find a free PowerPoint template that I designed specifically for scientific conference presentations. It holds six preformatted slide layouts which by default follow many of the academic conference slide design tips that we just went through, including the use of action titles, focus on visual information, and large enough font size. The presentation template also holds the three design tips to serve as a reminder from this post.

You will access these free Powerpoint scientific presentation slide templates in the download

Great slides will not mask poor presentation skills

Creating great presentation slides is certainly important in order to make a memorable academic presentation. But no amount of slide polishing will mask other potential problems, including lack of substance, unclear presentation structure, and a presenter who is so stressed their mouth feels like a desert.

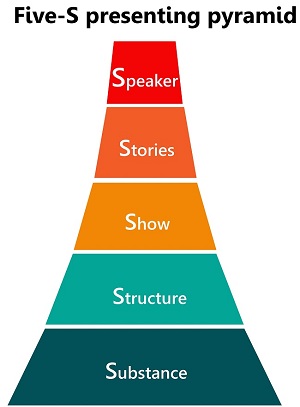

What you need is to add presentation skills to your scientific skill tool belt. My name is Martins Zaumanis and with my online course “Scientific Presentations Masterclass” I will show you how to become a masterful presenter using a system that I developed, called the “ Five S presenting pyramid ”.

Learn to give powerful academic presentations and overcome stage fright using the Five-S pyramid.

The Five-S pyramid starts from the basics of putting together the presentation Substance (first S), advances to devising a presentation Structure (second S), shows how to put up a Show (third S), tell memorable Stories (fourth S), and finally, it will offer advice for how the Speaker (fifth S) can work on improving presentation skills, including dealing with stage fright.

The Five-S pyramid starts from the basics of putting together the presentation Substance (first S), advances to devising a presentation Structure (second S), shows how to put up a Show (third S), tell memorable Stories (fourth S), and finally, it will offer advice for how the Speaker (fifth S) can work on improving presentation skills, including dealing with stage fright.

Related articles:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I want to join the Peer Recognized newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Copyright © 2024 Martins Zaumanis

Contacts: [email protected]

Privacy Policy

Research Conference Presentations: Some Tips and Examples

Useful Tips

Research talk 101 (by Lucia Dettori)

How not to give a presentation (from ScienceRoll)

Examples of Short Talks (PowerPoint files):

Mark's example of a bad research presentation

Mark's example of a somewhat better research presentation

Examples of Posters (PowerPoint files):

Poster example 1

Poster example 2

Poster example 3

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

Introduction | Introduction - main idea behind all studies |

Methods | Methods of study 1 |

Results | Results of study 1 |

Summary (take-home message ) of study 1 | |

Transition to study 2 (can be a visual of your main idea that return to) | |

Brief introduction for study 2 | |

Methods of study 2 | |

Results of study 2 | |

Summary of study 2 | |

Transition to study 3 | |

Repeat format until done | |

Summary | Summary of all studies (return to your main idea) |

Conclusion | Conclusion |

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

Get in touch

555-555-5555

Limited time offer: 20% off all templates ➞

Scientific Presentation Guide: How to Create an Engaging Research Talk

Creating an effective scientific presentation requires developing clear talking points and slide designs that highlight your most important research results..

Scientific presentations are detailed talks that showcase a research project or analysis results. This comprehensive guide reviews everything you need to know to give an engaging presentation for scientific conferences, lab meetings, and PhD thesis talks. From creating your presentation outline to designing effective slides, the tips in this article will give you the tools you need to impress your scientific peers and superiors.

Step 1. Create a Presentation Outline

The first step to giving a good scientific talk is to create a presentation outline that engages the audience at the start of the talk, highlights only 3-5 main points of your research, and then ends with a clear take-home message. Creating an outline ensures that the overall talk storyline is clear and will save you time when you start to design your slides.

Engage Your Audience

The first part of your presentation outline should contain slide ideas that will gain your audience's attention. Below are a few recommendations for slides that engage your audience at the start of the talk:

- Create a slide that makes connects your data or presentation information to a shared purpose, such as relevance to solving a medical problem or fundamental question in your field of research

- Create slides that ask and invite questions

- Use humor or entertainment

Identify Clear Main Points

After writing down your engagement ideas, the next step is to list the main points that will become the outline slide for your presentation. A great way to accomplish this is to set a timer for five minutes and write down all of the main points and results or your research that you want to discuss in the talk. When the time is up, review the points and select no more than three to five main points that create your talk outline. Limiting the amount of information you share goes a long way in maintaining audience engagement and understanding.

Create a Take-Home Message

And finally, you should brainstorm a single take-home message that makes the most important main point stand out. This is the one idea that you want people to remember or to take action on after your talk. This can be your core research discovery or the next steps that will move the project forward.

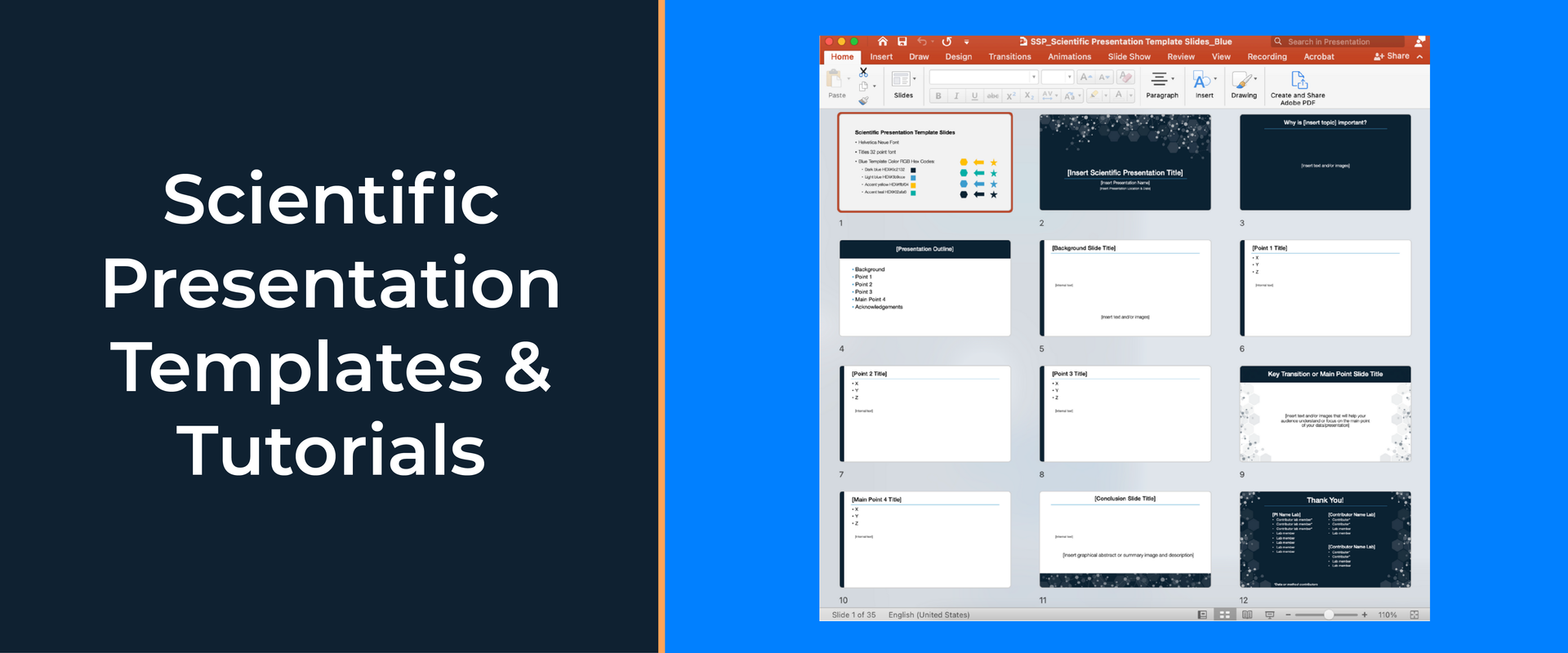

Step 2. Choose a Professional Slide Theme

After you have a good presentation outline, the next step is to choose your slide colors and create a theme. Good slide themes use between two to four main colors that are accessible to people with color vision deficiencies. Read this article to learn more about choosing the best scientific color palettes .

You can also choose templates that already have an accessible color scheme. However, be aware that many PowerPoint templates that are available online are too cheesy for a scientific audience. Below options to download professional scientific slide templates that are designed specifically for academic conferences, research talks, and graduate thesis defenses.

Step 3. Design Your Slides

Designing good slides is essential to maintaining audience interest during your scientific talk. Follow these four best practices for designing your slides:

- Keep it simple: limit the amount of information you show on each slide

- Use images and illustrations that clearly show the main points with very little text.

- Read this article to see research slide example designs for inspiration

- When you are using text, try to reduce the scientific jargon that is unnecessary. Text on research talk slides needs to be much more simple than the text used in scientific publications (see example below).

- Use appear/disappear animations to break up the details into smaller digestible bites

- Sign up for the free presentation design course to learn PowerPoint animation tricks

Scientific Presentation Design Summary

All of the examples and tips described in this article will help you create impressive scientific presentations. Below is the summary of how to give an engaging talk that will earn respect from your scientific community.

Step 1. Draft Presentation Outline. Create a presentation outline that clearly highlights the main point of your research. Make sure to start your talk outline with ideas to engage your audience and end your talk with a clear take-home message.

Step 2. Choose Slide Theme. Use a slide template or theme that looks professional, best represents your data, and matches your audience's expectations. Do not use slides that are too plain or too cheesy.

Step 3. Design Engaging Slides. Effective presentation slide designs use clear data visualizations and limits the amount of information that is added to each slide.

And a final tip is to practice your presentation so that you can refine your talking points. This way you will also know how long it will take you to cover the most essential information on your slides. Thank you for choosing Simplified Science Publishing as your science communication resource and good luck with your presentations!

Interested in free design templates and training?

Explore scientific illustration templates and courses by creating a Simplified Science Publishing Log In. Whether you are new to data visualization design or have some experience, these resources will improve your ability to use both basic and advanced design tools.

Interested in reading more articles on scientific design? Learn more below:

Data Storytelling Techniques: How to Tell a Great Data Story in 4 Steps

Best Science PowerPoint Templates and Slide Design Examples

Content is protected by Copyright license. Website visitors are welcome to share images and articles, however they must include the Simplified Science Publishing URL source link when shared. Thank you!

Online Courses

Stay up-to-date for new simplified science courses, subscribe to our newsletter.

Thank you for signing up!

You have been added to the emailing list and will only recieve updates when there are new courses or templates added to the website.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and we do not sell data. By using this website, you are giving your consent for us to set cookies: View Privacy Policy

Simplified Science Publishing, LLC

Home Blog Education How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

Since the dawn of time, humans were eager to find explanations for the world around them. At first, our scientific method was very simplistic and somewhat naive. We observed and reflected. But with the progressive evolution of research methods and thinking paradigms, we arrived into the modern era of enlightenment and science. So what represents the modern scientific method and how can you accurately share and present your research findings to others? These are the two fundamental questions we attempt to answer in this post.

What is the Scientific Method?

To better understand the concept, let’s start with this scientific method definition from the International Encyclopedia of Human Geography :

The scientific method is a way of conducting research, based on theory construction, the generation of testable hypotheses, their empirical testing, and the revision of theory if the hypothesis is rejected.

Essentially, a scientific method is a cumulative term, used to describe the process any scientist uses to objectively interpret the world (and specific phenomenon) around them.

The scientific method is the opposite of beliefs and cognitive biases — mostly irrational, often unconscious, interpretations of different occurrences that we lean on as a mental shortcut.

The scientific method in research, on the contrary, forces the thinker to holistically assess and test our approaches to interpreting data. So that they could gain consistent and non-arbitrary results.

The common scientific method examples are:

- Systematic observation

- Experimentation

- Inductive and deductive reasoning

- Formation and testing of hypotheses and theories

All of the above are used by both scientists and businesses to make better sense of the data and/or phenomenon at hand.

The Evolution of the Scientific Method

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ancient thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle are believed to be the forefathers of the scientific method. They were among the first to try to justify and refine their thought process using the scientific method experiments and deductive reasoning.

Both developed specific systems for knowledge acquisition and processing. For example, the Platonic way of knowledge emphasized reasoning as the main method for learning but downplayed the importance of observation. The Aristotelian corpus of knowledge, on the contrary, said that we must carefully observe the natural world to discover its fundamental principles.

In medieval times, thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, and Andreas Vesalius among many others worked on further clarifying how we can obtain proven knowledge through observation and induction.

The 16th–18th centuries are believed to have given the greatest advances in terms of scientific method application. We, humans, learned to better interpret the world around us from mechanical, biological, economic, political, and medical perspectives. Thinkers such as Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, and their followers also increasingly switched to a tradition of explaining everything through mathematics, geometry, and numbers.

Up till today, mathematical and mechanical explanations remain the core parts of the scientific method.

Why is the Scientific Method Important Today?

Because our ancestors didn’t have as much data as we do. We now live in the era of paramount data accessibility and connectivity, where over 2.5 quintillions of data are produced each day. This has tremendously accelerated knowledge creation.

But, at the same time, such overwhelming exposure to data made us more prone to external influences, biases, and false beliefs. These can jeopardize the objectivity of any research you are conducting.

Scientific findings need to remain objective, verifiable, accurate, and consistent. Diligent usage of scientific methods in modern business and science helps ensure proper data interpretation, results replication, and undisputable validity.

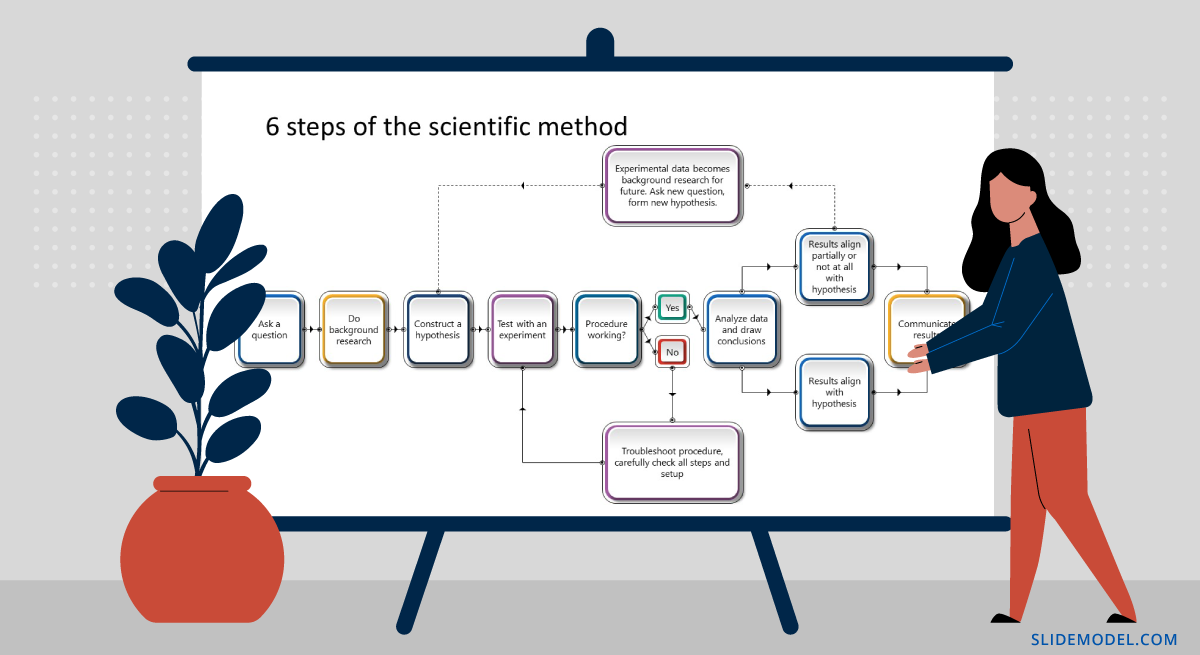

6 Steps of the Scientific Method

Over the course of history, the scientific method underwent many interactions. Yet, it still carries some of the integral steps our ancestors used to analyze the world such as observation and inductive reasoning. However, the modern scientific method steps differ a bit.

1. Make an Observation

An observation serves as a baseline for your research. There are two important characteristics for a good research observation:

- It must be objective, not subjective.

- It must be verifiable, meaning others can say it’s true or false with this.

For example, This apple is red (objective/verifiable observation). This apple is delicious (subjective, harder-to-verify observation).

2. Develop a Hypothesis

Observations tell us about the present or past. But the goal of science is to glean in the future. A scientific hypothesis is based on prior knowledge and produced through reasoning as an attempt to descriptive a future event.

Here are characteristics of a good scientific hypothesis:

- General and tentative idea

- Agrees with all available observations

- Testable and potentially falsifiable

Remember: If we state our hypothesis to indicate there is no effect, our hypothesis is a cause-and-effect relationship . A hypothesis, which asserts no effect, is called a null hypothesis.

3. Make a Prediction

A hypothesis is a mental “launchpad” for predicting the existence of other phenomena or quantitative results of new observations.

Going back to an earlier example here’s how to turn it into a hypothesis and a potential prediction for proving it. For example: If this apple is red, other apples of this type should be red too.

Your goal is then to decide which variables can help you prove or disprove your hypothesis and prepare to test these.

4. Perform an Experiment

Collect all the information around variables that will help you prove or disprove your prediction. According to the scientific method, a hypothesis has to be discarded or modified if its predictions are clearly and repeatedly incompatible with experimental results.

Yes, you may come up with an elegant theory. However, if your hypothetical predictions cannot be backed by experimental results, you cannot use them as a valid explanation of the phenomenon.

5. Analyze the Results of the Experiment

To come up with proof for your hypothesis, use different statistical analysis methods to interpret the meaning behind your data.

Remember to stay objective and emotionally unattached to your results. If 95 apples turned red, but 5 were yellow, does it disprove your hypothesis? Not entirely. It may mean that you didn’t account for all variables and must adapt the parameters of your experiment.

Here are some common data analysis techniques, used as a part of a scientific method:

- Statistical analysis

- Cause and effect analysis (see cause and effect analysis slides )

- Regression analysis

- Factor analysis

- Cluster analysis

- Time series analysis

- Diagnostic analysis

- Root cause analysis (see root cause analysis slides )

6. Draw a Conclusion

Every experiment has two possible outcomes:

- The results correspond to the prediction

- The results disprove the prediction

If that’s the latter, as a scientist you must discard the prediction then and most likely also rework the hypothesis based on it.

How to Give a Scientific Presentation to Showcase Your Methods

Whether you are doing a poster session, conference talk, or follow-up presentation on a recently published journal article, most of your peers need to know how you’ve arrived at the presented conclusions.

In other words, they will probe your scientific method for gaps to ensure that your results are fair and possible to replicate. So that they could incorporate your theories in their research too. Thus your scientific presentation must be sharp, on-point, and focus clearly on your research approaches.

Below we propose a quick framework for creating a compelling scientific presentation in PowerPoint (+ some helpful templates!).

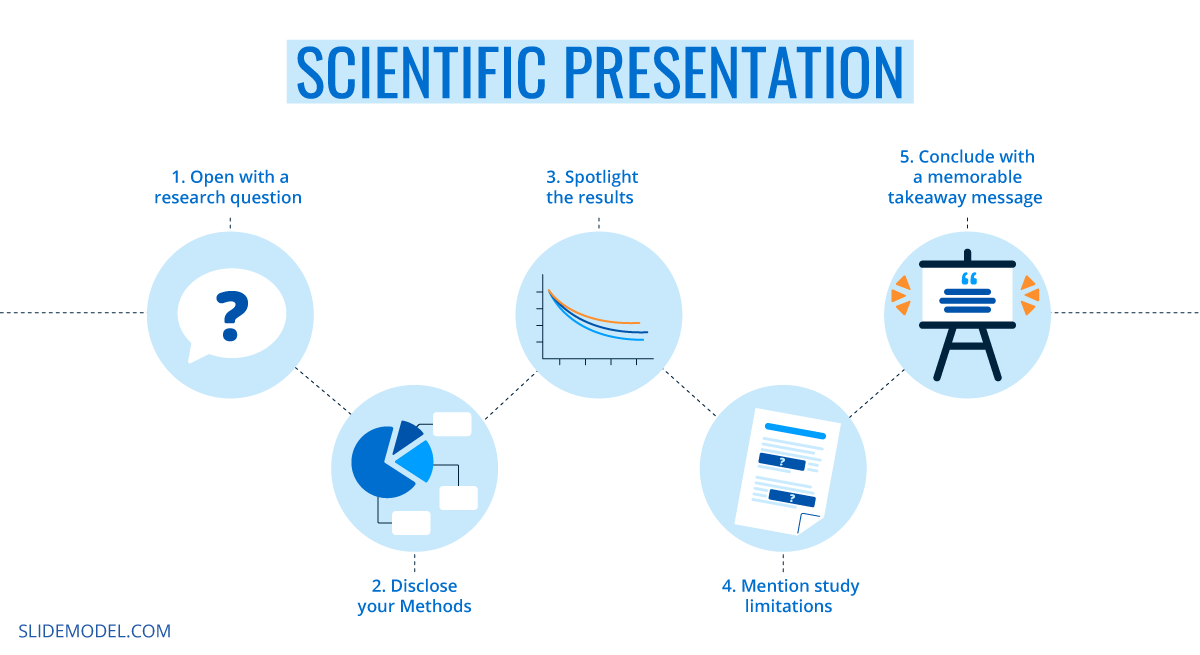

1. Open with a Research Question

Here’s how to start a scientific presentation with ease: share your research question. On the first slide, briefly recap how your thought process went. Briefly state what was the underlying aim of your research: Share your main hypothesis, mention if you could prove or disprove them.

It might be tempting to pack a lot of ideas into your first slide but don’t. Keep the opening of your presentation short to pique the audience’s initial interest and set the stage for the follow-up narrative.

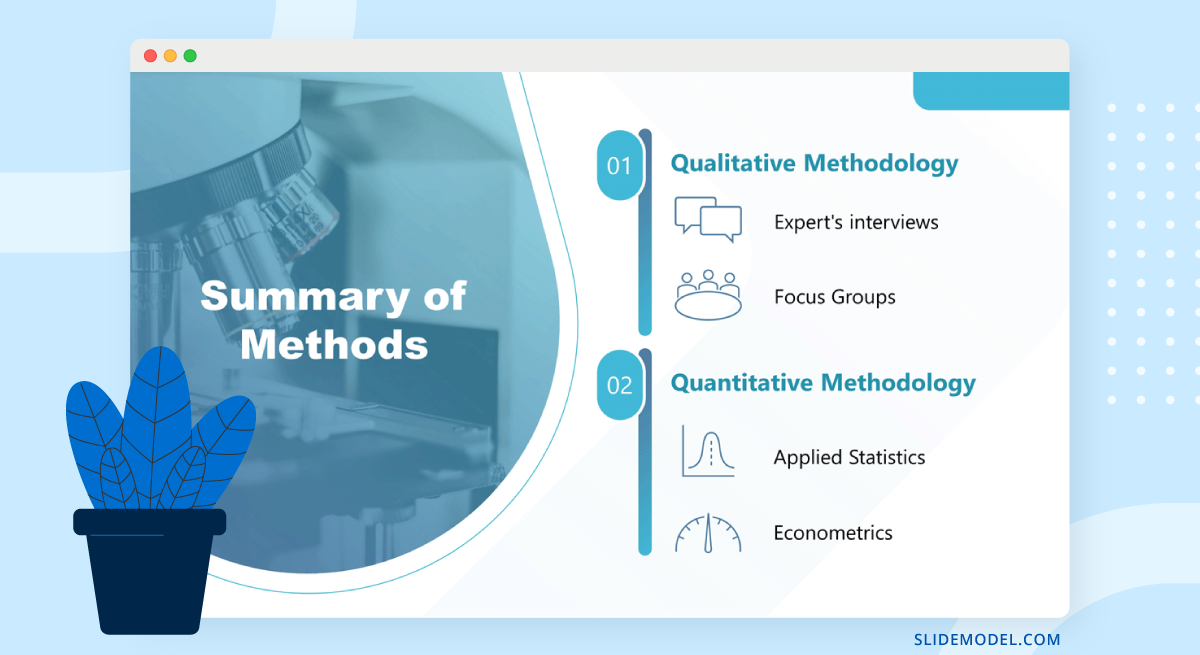

2. Disclose Your Methods

Whether you are doing a science poster presentation or conference talk, many audience members would be curious to understand how you arrived at your results. Deliver this information at the beginning of your presentation to avoid any ambiguities.

Here’s how to organize your science methods on a presentation:

- Do not use bullet points or full sentences. Use diagrams and structured images to list the methods

- Use visuals and iconography to use metaphors where possible.

- Organize your methods by groups e.g. quantifiable and non-quantifiable

Finally, when you work on visuals for your presentation — charts, graphs, illustrations, etc. — think from the perspective of a subject novice. Does the image really convey the key information around the subject? Does it help break down complex ideas?

3. Spotlight the Results

Obviously, the research results will be your biggest bragging right. However, don’t over-pack your presentation with a long-winded discussion of your findings and how revolutionary these may be for the community.

Rather than writing a wall of text, do this instead:

- Use graphs with large axis values/numbers to showcase the findings in great detail

- Prioritize formats that are known to everybody (e.g. odds ratios, Kaplan Meier curves, etc.)

- Do not include more than 5 lines of plain text per slide

Overall, when you feel that the results slide gets too cramped, it’s best to move the data to a new one.

Also, as you work on organizing data on your scientific presentation PowerPoint template , think if there are obvious limitations and gaps. If yes, make sure you acknowledge them during your speech.

4. Mention Study Limitations

The scientific method mandates objectivity. That’s why every researcher must clearly state what was excluded from their study. Remember: no piece of scientific research is truly universal and has certain boundaries. However, when you fail to personally state those, others might struggle to draw the line themselves and replicate your results. Then, if they fail to do so, they’d question the viability of your research.

5. Conclude with a Memorable Takeaway Message

Every experienced speaker will tell you that the audience best retains the information they hear first and last. Most people will attend more than one scientific presentation during the day.

So if you want the audience to better remember your talk, brainstorm a take-home message for the last slide of your presentation. Think of your last slide texts as an elevator pitch — a short, concluding message, summarizing your research.

To Conclude

Today we have no shortage of research and scientific methods for testing and proving our hypothesis. However, unlike our ancestors, most scientists experience deeper scrutiny when it comes to presenting and explaining their findings to others. That’s why it’s important to ensure that your scientific presentation clearly relays the aim, vector, and thought process behind your research.

Like this article? Please share

Education, Presentation Ideas, Presentation Skills, Presentation Tips Filed under Education

Related Articles

Filed under Design • October 17th, 2024

Architecture Project Presentation: Must-Know Secrets for Creative Slides

Impress your audience by mastering the art of architectural project presentations. This detailed guide will give you the insights for this craft.

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • October 16th, 2024

How to Add Voice Memos to Google Slides

Make your slides more interesting by learning how to add voice memos to Google Slides presentations. Step-by-step instructions here.

Filed under Business • October 8th, 2024

Data-Driven Decision Making: Presenting the Process Behind Informed Choices

Discover how to harness data for informed decision-making and create impactful presentations. A detailed guide + templates on DDDM presentation slides.

Leave a Reply

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In the course of your career as a scientist, you will be asked to give brief presentations -- to colleagues, lab groups, and in other venues. We have put together a series of short videos to help you organize and deliver a crisp 10-15 minute scientific presentation.

In this post, you will learn three crucial tips for preparing scientific conference presentation slides to efficiently explain your research. Tip No.1: One thought per slide. Tip No.2: Presentation slides are for visual information. Tip No.3: Use action titles

Research Conference Presentations: Some Tips and Examples. Useful Tips. Research talk 101 (by Lucia Dettori) How not to give a presentation (from ScienceRoll) Examples of Short Talks (PowerPoint files): Mark's example of a bad research presentation.

This guide provides a 4-step process for making a good scientific presentation: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slide outlines, constructing slides, and practicing the talk. We give advice on how to make effective slides, including tips for text, graphics, and equations, and how to use rehearsals of your talk to refine your ...

Scientific presentations are detailed talks that showcase a research project or analysis results. This comprehensive guide reviews everything you need to know to give an engaging presentation for scientific conferences, lab meetings, and PhD thesis talks.

Learn how to prepare a scientific method presentation slides in PowerPoint or Google Slides to present your scientific projects.