popular searches

- Request Info

Suggested Ways to Introduce Quotations

When you quote another writer's words, it's best to introduce or contextualize the quote.

How To Quote In An Essay?

To introduce a quote in an essay , don't forget to include author's last name and page number (MLA) or author, date, and page number (APA) in your citation. Shown below are some possible ways to introduce quotations. The examples use MLA format.

Use A Full Sentence Followed by A Colon To Introduce A Quotation

- The setting emphasizes deception: "Nothing is as it appears" (Smith 1).

- Piercy ends the poem on an ironic note: "To every woman a happy ending" (25).

Begin A Sentence with Your Own Words, Then Complete It with Quoted Words

Note that in the second example below, a slash with a space on either side ( / ) marks a line break in the original poem.

- Hamlet's task is to avenge a "foul and most unnatural murder" (Shakespeare 925).

- The speaker is mystified by her sleeping baby, whose "moth-breath / flickers among the flat pink roses" (Plath 17).

Use An Introductory Phrase Naming The Source, Followed By A Comma to Quote A Critic or Researcher

Note that the first letter after the quotation marks should be upper case. According to MLA guidelines, if you change the case of a letter from the original, you must indicate this with brackets. APA format doesn't require brackets.

- According to Smith, "[W]riting is fun" (215).

- In Smith's words, " . . .

- In Smith's view, " . . .

Use A Descriptive Verb, Followed by A Comma To Introduce A Critic's Words

Avoid using says unless the words were originally spoken aloud, for instance, during an interview.

- Smith states, "This book is terrific" (102).

- Smith remarks, " . . .

- Smith writes, " . . .

- Smith notes, " . . .

- Smith comments, " . . .

- Smith observes, " . . .

- Smith concludes, " . . .

- Smith reports, " . . .

- Smith maintains, " . . .

- Smith adds, " . . .

Don't Follow It with A Comma If Your Lead into The Quotation Ends in That or As

The first letter of the quotation should be lower case.

- Smith points out that "millions of students would like to burn this book" (53).

- Smith emphasizes that " . . .

- Smith interprets the hand washing in MacBeth as "an attempt at absolution" (106).

- Smith describes the novel as "a celebration of human experience" (233).

Other Writing Resources

Enhance your academic writing skills by exploring our additional writing resources that will help you craft compelling essays, research papers, and more.

Your New Chapter Starts Wherever You Are

The support you need and education you deserve, no matter where life leads.

because a future built by you is a future built for you.

Too many people have been made to feel that higher education isn’t a place for them— that it is someone else’s dream. But we change all that. With individualized attention and ongoing support, we help you write a new story for the future where you play the starring role.

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Phrases for introducing sources and quotations.

This handout is available for download in DOCX format and PDF format .

Capturing Authorial Action through Summaries or Paraphrasing

These phrases alert your reader that you as a writer are about to summarize or paraphrase another idea established by an authority on a chosen topic. Note that while some of these are quite neutral, others allow you to imply things about the quote’s tone, similarity, contrast, and/or significance in relation to other sources or to your larger argument.

Author X…

- acknowledges that [blank].

- agrees that [blank].

- argues that [blank].

- believes that [blank].

- celebrates the fact that [blank].

- claims that [blank].

- complains that [blank].

- concedes that [blank].

- demonstrates that [blank].

- deplores the tendency to [blank].

- denies/does not deny that [blank].

- emphasizes that [blank].

- insists that [blank].

- maintains that [blank].

- observes that [blank].

- opines that [blank].

- questions whether [blank].

- refutes the claim that [blank].

- reminds us that [blank].

- reports that [blank].

- suggests that [blank].

- urges us to [blank].

Introducing Quotations

These phrases alert your reader that you are about to quote directly from another source. As with the phrases above, some are quite neutral, while others allow you to imply things about the quote’s tone, similarity, contrast, and/or significance in relation to other sources or to your larger argument.

- X states, “ [blank] .”

- As X puts it, “ [blank] .”

- According to X, “ [blank] .”

- X writes, “ [blank] .”

- In her book/essay [blank] , X maintains that “ [blank] .”

- Writing in the journal [blank] , X complains that “ [blank] .”

- In X's view, “ [blank] .”

- X agrees when she writes, “ [blank] .”

- X disagrees when he writes, “ [blank] .”

- X complicates matters further when they write, “ [blank] .”

Explaining Quotations

Remember that every paragraph must provide clarification, interpretation, or necessary analysis of a supplied quotation or paraphrase; this allows you to explain not only the quote itself, but how it fits into your larger argument. The phrases listed here are just some of the ways in which you can alert your reader that you are about to rephrase, clarify, expand, and otherwise analyze the source you have previously introduced.

- Basically/Essentially, X is saying [blank] .

- In other words, X believes [blank] .

- In making this comment, X urges us to [blank] .

- X is corroborating the idea that [blank] .

- X's point is that [blank] .

- The core/gist/meaning/significance of X' s argument is that [blank] .

And of course, remember that all outside sources must be cited correctly! For more information on how to effectively and accurately incorporate outside sources into your writing, please refer to the handout on “Working with Quotations.”

Adapted from Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, They Say/I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014) and David Glen Smith (http://www.davidglensmith.com/Tomball/supplemental/signal-phrases.pdf) by Robert B. Cochran, Brandeis University Writing Program, 2020.

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

Writing Studio

Who said what introducing and contextualizing quotations.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Introducing and Contextualizing Quotations Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Quotations (as well as paraphrases and summaries) play an essential role in academic writing, from literary analyses to scientific research papers; they are part of a writer’s ever-important evidence, or support, for his or her argument.

But oftentimes, writers aren’t sure how to incorporate quotes and thus shove them into paragraphs without much attention to logic or style.

For better quotations (and better writing), try these tips.

Identify Clearly Where the Borrowed Material Begins

The quotation should include a signal phrase, or introductory statement, which tells the reader whom or what you are citing. The phrase may indicate the author’s name or credentials, the title of the source, and/or helpful background information.

Sample signal phrases

- According to (author/article)

- Author + verb

Some key verbs for signal phrases

- says, writes, accepts, criticizes, describes, disagrees, discusses, explains, identifies, insists, offers, points out, suggests, warns

Two Signal Phrase Examples

- According to scholar Mary Poovey, Shelley’s narrative structure, which allows the creature to speak from a first-person point of view, forces the reader “to identify with [the creature’s] anguish and frustration” (259).

- In an introduction to Frankenstein in 1831, the author Mary Shelley describes even her own creative act with a sense of horror: “The idea so possessed my mind, that a thrill of fear ran through me, and I wished to exchange that ghastly image of my fancy for the realities around” (172).

Create Context for the Material

Don’t just plop in quotes and expect the reader to understand. Explain, expand, or refute the quote. Remember, quotations should be used to support your ideas and points.

Here’s one simple, useful pattern: Introduce quote, give quote, explain quote.

“Introduce, Give, Explain” Example 1

[Introduce] Dorianne Laux’s “Girl in the Doorway” uses many metaphors to evoke a sense of change between the mother and daughter: [Give] “I stand at the dryer, listening/through the thin wall between us, her voice/rising and falling as she describes her new life” (3-5). [Explain] The “thin wall” is literal but also references their communication barrier; “rising and falling” is the sound of the girl’s voice but also a reference to her tumultuous preteen emotions.

“Introduce, Give, Explain” Example 2 (longer block quotation)

[Introduce] After watching the cottagers with pleasure, Frankenstein’s creature has a startling moment of revelation and horror when he sees his own reflection for the first time:

[Give] I had admired the perfect forms of my cottagers — their grace, beauty, and delicate complexions: but how was I terrified, when I viewed myself in a transparent pool! At first I started back, unable to believe that it was indeed I who was reflected in the mirror; and when I became fully convinced that I was in reality the monster that I am, I was filled with the bitterest sensations of despondence and mortification. Alas! I did not yet entirely know the fatal effects of this miserable deformity. (76)

[Explain] This literal moment of reflection is key in the creature’s growing reflection of self: In comparing himself with humans, he sees himself not just as different but as “the monster that I am.”

Additional Advice

Pay attention to proper format and grammar (See VU Writing Studio handout Quotation Basics: Grammar, Punctuation, and Style ), and always, always credit your source in order to avoid plagiarism.

Citation styles (e.g. MLA, APA, or Chicago) vary by discipline. Ask your professor if you are uncertain, and then check style guides for formats. (The above examples use MLA format.)

Last revised: 06/2008 | Adapted for web delivery: 06/2021

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Introduce Quotes in Academic Writing

- 3-minute read

- 17th October 2019

It would be hard to write a good essay without quoting sources. And as well as using quote marks , this means working quotations into your own writing. But how can you do this? In this post, we provide a few helpful tips on how to introduce quotes (short and long) in academic writing.

Introducing Short Quotations

The easiest way to quote a source is to work a short passage (sometimes just a single word) into your own sentence. For example:

The tomb was one of archaeology’s “most intriguing discoveries” (Andronicus, 1978, p. 55) and has fascinated researchers ever since.

Here, the only requirements placing the quoted text within quotation marks and making sure the quote follows grammatically from the surrounding text.

Quoting After a Colon

If you need to quote a source after a full sentence, introduce it with a colon:

On the basis of Philip II’s estimated date of death, Andronicus (1978) draws a conclusion : “This, in all probability, must be his tomb” (p. 76).

When using a colon to introduce a quotation, the text before the colon must be a full sentence. The text after the colon, however, can be just a few words.

Quoting After a Comma

Alternatively, you can use a comma to introduce a quote. When doing this, the quoted text should follow from the preceding sentence (usually after a word like “says” or “argues”):

Andronicus (1978) says , “The weapons bore witness that the tomb could not have belonged to a commoner” (p. 73).

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

However, when a quote follows the word “that,” no comma is needed:

Andronicus (1978) says that “The weapons bore witness that the tomb could not have belonged to a commoner” (p. 73).

Block Quotes

Finally, for longer quotations, use a block quote . These are also introduced with a colon, but they don’t have to follow a full sentence. Furthermore, quoted text should be indented and the block quote should begin on a new line. For example, we could introduce a block quote as follows:

Andronicus (1978) describes the fresco in the following terms:

The barely visible painting depicts three hunters with spears and five horsemen with dogs pursuing their prey, wild boars and lions. This and three other paintings discovered in the adjacent tomb are among the few extant examples of fourth-century BC Greek frescoes. (p. 72)

This emphasizes how important the discovery was for understanding…

Usually, you’ll only need block quotes for passages with more than 40 words (or four lines). The exact rules depend on the reference system you’re using, though, so be sure to check your style guide. And, when in doubt, you can always submit a document for proofreading . We can help make sure your quotations are fully integrated into the rest of your text.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Get creative with full-sentence rewrites

Polish your papers with one click, avoid unintentional plagiarism.

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction in 4 Steps

Published on July 2, 2024 by Hannah Skaggs . Revised on September 11, 2024.

Having a hard time learning how to write a research paper introduction? Follow these four steps:

- Draw readers in.

- Zoom in on your topic and its importance.

- Explain how you’ll add new knowledge.

- Tell readers what they’ll find in your paper.

To understand why a great introduction matters, imagine a friend inviting you to lunch with another friend of hers. You show up at the restaurant and find them waiting for you at the table. You sit down, and her friend says, “So I wanna tell you about my major goal in life.”

Pretty awkward, right? You don’t even know this guy’s name yet, and he’s already diving into the heavy stuff. You’d probably prefer to have your friend introduce him, then spend some time learning about his background and personality before you get into deeper conversation.

Research paper readers need this kind of warmup, too. A good introduction, or intro, lives up to its name—it introduces readers to the topic. It prepares them to care about and understand your research, and it’s more convincing.

Free Grammar Checker

Table of contents

Steps to write a research paper introduction, tips for writing a research paper introduction, tools for writing a research paper introduction, frequently asked questions about how to write a research paper.

By following the steps below, you can learn how to write an introduction for a research paper that helps readers “shake hands” with your topic. In each step, thinking about the answers to key questions can help you reach your readers.

1. Get your readers’ attention

To speak to your readers effectively, you need to know who they are. Consider who is likely to read the paper and the extent of their knowledge on the topic. Then begin your introduction with a sentence or two that will capture their interest.

For instance, you might begin with an interesting quote or an example of a situation that illustrates your argument (as we did above). Or you could start by simply stating a fact that most people aren’t aware of, which may be a better approach in scientific fields. Whichever method you choose, remember that this is academic writing —keep your phrasing formal and don’t sensationalize.

Key questions:

- Who is your audience?

- What will your paper talk about?

- What will grab your audience’s interest in the topic?

2. Explain why your topic matters

Just as you’d like to understand where a new acquaintance is coming from as you get to know them, your readers want to understand the background of your research. Once you’ve got their attention, explain why they should care.

You can give background for your research by discussing previous research on the topic. While this part should be shorter than a literature review , it can explore some of the same kinds of connections and themes. Make sure the sources you cite relate to the argument you’re making or the problem you want to solve. The information you provide here should lay a factual foundation for your research.

- Why should readers care about your topic?

- What do readers need to know to understand your research?

- What have other researchers said about the topic?

- What is the field’s overall view of the topic?

3. Lay out your argument and plan

After showing your reader the existing knowledge on the topic, you can turn to how your paper will contribute new knowledge. Tying your research to previous research is the most important aspect of this step.

Explain what knowledge is missing from the existing research and how you plan to uncover that knowledge. This is the most common place for the thesis statement, which succinctly tells readers the purpose and main idea of your paper (though it could also appear at the end of Step 4).

- How does your research relate to the studies you described in Step 2?

- What question are you aiming to answer , or what problem are you looking to solve?

- What methods will you use to answer that question or solve that problem?

4. Define your direction

Besides introducing your readers to the topic and your related findings or argument, you’re introducing them to your research process and the paper itself. This means you need to help them understand how the paper is organized and where it’s going. Add a sentence, or a few sentences, describing the sections of your paper in order or the main ideas it will cover.

While longer papers typically need to include this step, shorter ones, such as a five-paragraph essay , can usually skip it. In these cases, the thesis statement outlines the paper’s structure.

- What goal will each section of your paper accomplish?

- What should readers take away from your paper?

As you go through the steps above, keep in mind the principles of quality academic writing. Specifically, understanding how to organize and summarize will empower you to complete each step with excellence.

Keep it smooth

A good flow helps readers follow your logic. As you progress from Step 1 to Step 4, the information you give should grow more and more specific. It’s similar to how, when you meet a person, you learn basics like their name and appearance first. Then you learn about their background and more specific details, like their political views.

To make your introduction flow, start with an outline. The outline functions like a skeleton. It provides a structure for the details that make up your introduction like muscles and other tissues. It helps you make sure you don’t miss any important elements. Then, as you flesh out the details, use transition words and phrases between them to show how they relate to each other.

Keep it brief

How long should a research paper introduction be? It depends on the overall length of your paper, but the intro is typically one of the shortest sections. For example, in a short paper like an essay, you can complete each of the steps above in just a sentence or two. But in a longer one, such as a dissertation , each step may take a couple of paragraphs.

In a sense, the intro is a summary of the rest of the paper, and summarizing is all about prioritizing. As business guru Karen Martin said, “When everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.”

Martin was talking about deciding which tasks are more urgent in a business, but the same principle applies to summarizing. You must decide which ideas are the most fundamental and leave the rest out. Think about it: when you’re first meeting someone, they don’t give you an exhaustive list of all their traits. They introduce themselves with just a few of their most prominent ones.

Besides narrowing your focus, another way to keep your introduction short is to write concisely. Plain, direct language helps hold the reader’s attention, but wordy sentences will make them nod off and lose interest.

Since the introduction of a research paper is basically a summary, you may find it helpful to write it last, after you’ve finished the rest of your paper. If you write it first, there’s a good chance you’ll have to change some of its main points later. This can happen because the other sections of your paper, which your intro is based on, may evolve while you’re writing them.

Of course, you should always go back and take a second or even third look at every section of your research paper to check for errors and other necessary changes. But if you write your intro last, editing it is likely to take much less time.

Now that we’ve introduced you to the basics of writing a research paper introduction, we’d like to introduce you to QuillBot. At every step of writing your intro, it can help you upgrade your writing skills:

- Cite sources using the Citation Generator .

- Avoid plagiarism using the Plagiarism Checker .

- Reword statements from previous research (but still cite them) using the Paraphraser .

- Write spectacular and concise thesis statements (or even your whole introduction section!) using the Summarizer .

A research paper introduction starts by acquainting readers with the topic generally. Then it explores the background of the research. Finally, it explains the specific purpose of the research and its contribution.

Quotes , anecdotes, and interesting facts are all effective hooks to begin the introduction of a research paper. Which one you choose depends on the subject of your paper and your field of study.

Is this article helpful?

Hannah Skaggs

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

How to write an effective introduction for your research paper

Last updated

20 January 2024

Reviewed by

However, the introduction is a vital element of your research paper . It helps the reader decide whether your paper is worth their time. As such, it's worth taking your time to get it right.

In this article, we'll tell you everything you need to know about writing an effective introduction for your research paper.

- The importance of an introduction in research papers

The primary purpose of an introduction is to provide an overview of your paper. This lets readers gauge whether they want to continue reading or not. The introduction should provide a meaningful roadmap of your research to help them make this decision. It should let readers know whether the information they're interested in is likely to be found in the pages that follow.

Aside from providing readers with information about the content of your paper, the introduction also sets the tone. It shows readers the style of language they can expect, which can further help them to decide how far to read.

When you take into account both of these roles that an introduction plays, it becomes clear that crafting an engaging introduction is the best way to get your paper read more widely. First impressions count, and the introduction provides that impression to readers.

- The optimum length for a research paper introduction

While there's no magic formula to determine exactly how long a research paper introduction should be, there are a few guidelines. Some variables that impact the ideal introduction length include:

Field of study

Complexity of the topic

Specific requirements of the course or publication

A commonly recommended length of a research paper introduction is around 10% of the total paper’s length. So, a ten-page paper has a one-page introduction. If the topic is complex, it may require more background to craft a compelling intro. Humanities papers tend to have longer introductions than those of the hard sciences.

The best way to craft an introduction of the right length is to focus on clarity and conciseness. Tell the reader only what is necessary to set up your research. An introduction edited down with this goal in mind should end up at an acceptable length.

- Evaluating successful research paper introductions

A good way to gauge how to create a great introduction is by looking at examples from across your field. The most influential and well-regarded papers should provide some insights into what makes a good introduction.

Dissecting examples: what works and why

We can make some general assumptions by looking at common elements of a good introduction, regardless of the field of research.

A common structure is to start with a broad context, and then narrow that down to specific research questions or hypotheses. This creates a funnel that establishes the scope and relevance.

The most effective introductions are careful about the assumptions they make regarding reader knowledge. By clearly defining key terms and concepts instead of assuming the reader is familiar with them, these introductions set a more solid foundation for understanding.

To pull in the reader and make that all-important good first impression, excellent research paper introductions will often incorporate a compelling narrative or some striking fact that grabs the reader's attention.

Finally, good introductions provide clear citations from past research to back up the claims they're making. In the case of argumentative papers or essays (those that take a stance on a topic or issue), a strong thesis statement compels the reader to continue reading.

Common pitfalls to avoid in research paper introductions

You can also learn what not to do by looking at other research papers. Many authors have made mistakes you can learn from.

We've talked about the need to be clear and concise. Many introductions fail at this; they're verbose, vague, or otherwise fail to convey the research problem or hypothesis efficiently. This often comes in the form of an overemphasis on background information, which obscures the main research focus.

Ensure your introduction provides the proper emphasis and excitement around your research and its significance. Otherwise, fewer people will want to read more about it.

- Crafting a compelling introduction for a research paper

Let’s take a look at the steps required to craft an introduction that pulls readers in and compels them to learn more about your research.

Step 1: Capturing interest and setting the scene

To capture the reader's interest immediately, begin your introduction with a compelling question, a surprising fact, a provocative quote, or some other mechanism that will hook readers and pull them further into the paper.

As they continue reading, the introduction should contextualize your research within the current field, showing readers its relevance and importance. Clarify any essential terms that will help them better understand what you're saying. This keeps the fundamentals of your research accessible to all readers from all backgrounds.

Step 2: Building a solid foundation with background information

Including background information in your introduction serves two major purposes:

It helps to clarify the topic for the reader

It establishes the depth of your research

The approach you take when conveying this information depends on the type of paper.

For argumentative papers, you'll want to develop engaging background narratives. These should provide context for the argument you'll be presenting.

For empirical papers, highlighting past research is the key. Often, there will be some questions that weren't answered in those past papers. If your paper is focused on those areas, those papers make ideal candidates for you to discuss and critique in your introduction.

Step 3: Pinpointing the research challenge

To capture the attention of the reader, you need to explain what research challenges you'll be discussing.

For argumentative papers, this involves articulating why the argument you'll be making is important. What is its relevance to current discussions or problems? What is the potential impact of people accepting or rejecting your argument?

For empirical papers, explain how your research is addressing a gap in existing knowledge. What new insights or contributions will your research bring to your field?

Step 4: Clarifying your research aims and objectives

We mentioned earlier that the introduction to a research paper can serve as a roadmap for what's within. We've also frequently discussed the need for clarity. This step addresses both of these.

When writing an argumentative paper, craft a thesis statement with impact. Clearly articulate what your position is and the main points you intend to present. This will map out for the reader exactly what they'll get from reading the rest.

For empirical papers, focus on formulating precise research questions and hypotheses. Directly link them to the gaps or issues you've identified in existing research to show the reader the precise direction your research paper will take.

Step 5: Sketching the blueprint of your study

Continue building a roadmap for your readers by designing a structured outline for the paper. Guide the reader through your research journey, explaining what the different sections will contain and their relationship to one another.

This outline should flow seamlessly as you move from section to section. Creating this outline early can also help guide the creation of the paper itself, resulting in a final product that's better organized. In doing so, you'll craft a paper where each section flows intuitively from the next.

Step 6: Integrating your research question

To avoid letting your research question get lost in background information or clarifications, craft your introduction in such a way that the research question resonates throughout. The research question should clearly address a gap in existing knowledge or offer a new perspective on an existing problem.

Tell users your research question explicitly but also remember to frequently come back to it. When providing context or clarification, point out how it relates to the research question. This keeps your focus where it needs to be and prevents the topic of the paper from becoming under-emphasized.

Step 7: Establishing the scope and limitations

So far, we've talked mostly about what's in the paper and how to convey that information to readers. The opposite is also important. Information that's outside the scope of your paper should be made clear to the reader in the introduction so their expectations for what is to follow are set appropriately.

Similarly, be honest and upfront about the limitations of the study. Any constraints in methodology, data, or how far your findings can be generalized should be fully communicated in the introduction.

Step 8: Concluding the introduction with a promise

The final few lines of the introduction are your last chance to convince people to continue reading the rest of the paper. Here is where you should make it very clear what benefit they'll get from doing so. What topics will be covered? What questions will be answered? Make it clear what they will get for continuing.

By providing a quick recap of the key points contained in the introduction in its final lines and properly setting the stage for what follows in the rest of the paper, you refocus the reader's attention on the topic of your research and guide them to read more.

- Research paper introduction best practices

Following the steps above will give you a compelling introduction that hits on all the key points an introduction should have. Some more tips and tricks can make an introduction even more polished.

As you follow the steps above, keep the following tips in mind.

Set the right tone and style

Like every piece of writing, a research paper should be written for the audience. That is to say, it should match the tone and style that your academic discipline and target audience expect. This is typically a formal and academic tone, though the degree of formality varies by field.

Kno w the audience

The perfect introduction balances clarity with conciseness. The amount of clarification required for a given topic depends greatly on the target audience. Knowing who will be reading your paper will guide you in determining how much background information is required.

Adopt the CARS (create a research space) model

The CARS model is a helpful tool for structuring introductions. This structure has three parts. The beginning of the introduction establishes the general research area. Next, relevant literature is reviewed and critiqued. The final section outlines the purpose of your study as it relates to the previous parts.

Master the art of funneling

The CARS method is one example of a well-funneled introduction. These start broadly and then slowly narrow down to your specific research problem. It provides a nice narrative flow that provides the right information at the right time. If you stray from the CARS model, try to retain this same type of funneling.

Incorporate narrative element

People read research papers largely to be informed. But to inform the reader, you have to hold their attention. A narrative style, particularly in the introduction, is a great way to do that. This can be a compelling story, an intriguing question, or a description of a real-world problem.

Write the introduction last

By writing the introduction after the rest of the paper, you'll have a better idea of what your research entails and how the paper is structured. This prevents the common problem of writing something in the introduction and then forgetting to include it in the paper. It also means anything particularly exciting in the paper isn’t neglected in the intro.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Research Paper Introduction Examples

Looking for research paper introduction examples? Quotes, anecdotes, questions, examples, and broad statements—all of them can be used successfully to write an introduction for a research paper. It’s instructive to see them in action, in the hands of skilled academic writers.

Let’s begin with David M. Kennedy’s superb history, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . Kennedy begins each chapter with a quote, followed by his text. The quote above chapter 1 shows President Hoover speaking in 1928 about America’s golden future. The text below it begins with the stock market collapse of 1929. It is a riveting account of just how wrong Hoover was. The text about the Depression is stronger because it contrasts so starkly with the optimistic quotation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

“We in America today are nearer the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.”—Herbert Hoover, August 11, 1928 Like an earthquake, the stock market crash of October 1929 cracked startlingly across the United States, the herald of a crisis that was to shake the American way of life to its foundations. The events of the ensuing decade opened a fissure across the landscape of American history no less gaping than that opened by the volley on Lexington Common in April 1775 or by the bombardment of Sumter on another April four score and six years later. (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); The ratcheting ticker machines in the autumn of 1929 did not merely record avalanching stock prices. In time they came also to symbolize the end of an era. (David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 10)

Kennedy has exciting, wrenching material to work with. John Mueller faces the exact opposite problem. In Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War , he is trying to explain why Great Powers have suddenly stopped fighting each other. For centuries they made war on each other with devastating regularity, killing millions in the process. But now, Mueller thinks, they have not just paused; they have stopped permanently. He is literally trying to explain why “nothing is happening now.” That may be an exciting topic intellectually, it may have great practical significance, but “nothing happened” is not a very promising subject for an exciting opening paragraph. Mueller manages to make it exciting and, at the same time, shows why it matters so much. Here’s his opening, aptly entitled “History’s Greatest Nonevent”:

On May 15, 1984, the major countries of the developed world had managed to remain at peace with each other for the longest continuous stretch of time since the days of the Roman Empire. If a significant battle in a war had been fought on that day, the press would have bristled with it. As usual, however, a landmark crossing in the history of peace caused no stir: the most prominent story in the New York Times that day concerned the saga of a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest. This book seeks to develop an explanation for what is probably the greatest nonevent in human history. (John Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War . New York: Basic Books, 1989, p. 3)

In the space of a few sentences, Mueller sets up his puzzle and reveals its profound human significance. At the same time, he shows just how easy it is to miss this milestone in the buzz of daily events. Notice how concretely he does that. He doesn’t just say that the New York Times ignored this record setting peace. He offers telling details about what they covered instead: “a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest.” Likewise, David Kennedy immediately entangles us in concrete events: the stunning stock market crash of 1929. These are powerful openings that capture readers’ interests, establish puzzles, and launch narratives.

Sociologist James Coleman begins in a completely different way, by posing the basic questions he will study. His ambitious book, Foundations of Social Theory , develops a comprehensive theory of social life, so it is entirely appropriate for him to begin with some major questions. But he could just as easily have begun with a compelling story or anecdote. He includes many of them elsewhere in his book. His choice for the opening, though, is to state his major themes plainly and frame them as a paradox. Sociologists, he says, are interested in aggregate behavior—how people act in groups, organizations, or large numbers—yet they mostly examine individuals:

A central problem in social science is that of accounting for the function of some kind of social system. Yet in most social research, observations are not made on the system as a whole, but on some part of it. In fact, the natural unit of observation is the individual person… This has led to a widening gap between theory and research… (James S. Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990, pp. 1–2)

After expanding on this point, Coleman explains that he will not try to remedy the problem by looking solely at groups or aggregate-level data. That’s a false solution, he says, because aggregates don’t act; individuals do. So the real problem is to show the links between individual actions and aggregate outcomes, between the micro and the macro.

The major problem for explanations of system behavior based on actions and orientations at a level below that of the system [in this case, on individual-level actions] is that of moving from the lower level to the system level. This has been called the micro-to-macro problem, and it is pervasive throughout the social sciences. (Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory , p. 6)

Explaining how to deal with this “micro-to-macro problem” is the central issue of Coleman’s book, and he announces it at the beginning.

Coleman’s theory-driven opening stands at the opposite end of the spectrum from engaging stories or anecdotes, which are designed to lure the reader into the narrative and ease the path to a more analytic treatment later in the text. Take, for example, the opening sentences of Robert L. Herbert’s sweeping study Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society : “When Henry Tuckerman came to Paris in 1867, one of the thousands of Americans attracted there by the huge international exposition, he was bowled over by the extraordinary changes since his previous visit twenty years before.” (Robert L. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988, p. 1.) Herbert fills in the evocative details to set the stage for his analysis of the emerging Impressionist art movement and its connection to Parisian society and leisure in this period.

David Bromwich writes about Wordsworth, a poet so familiar to students of English literature that it is hard to see him afresh, before his great achievements, when he was just a young outsider starting to write. To draw us into Wordsworth’s early work, Bromwich wants us to set aside our entrenched images of the famous mature poet and see him as he was in the 1790s, as a beginning writer on the margins of society. He accomplishes this ambitious task in the opening sentences of Disowned by Memory: Wordsworth’s Poetry of the 1790s :

Wordsworth turned to poetry after the revolution to remind himself that he was still a human being. It was a curious solution, to a difficulty many would not have felt. The whole interest of his predicament is that he did feel it. Yet Wordsworth is now so established an eminence—his name so firmly fixed with readers as a moralist of self-trust emanating from complete self-security—that it may seem perverse to imagine him as a criminal seeking expiation. Still, that is a picture we get from The Borderers and, at a longer distance, from “Tintern Abbey.” (David Bromwich, Disowned by Memory: Wordsworth’s Poetry of the 1790s . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 1)

That’s a wonderful opening! Look at how much Bromwich accomplishes in just a few words. He not only prepares the way for analyzing Wordsworth’s early poetry; he juxtaposes the anguished young man who wrote it to the self-confident, distinguished figure he became—the eminent man we can’t help remembering as we read his early poetry.

Let us highlight a couple of other points in this passage because they illustrate some intelligent writing choices. First, look at the odd comma in this sentence: “It was a curious solution, to a difficulty many would not have felt.” Any standard grammar book would say that comma is wrong and should be omitted. Why did Bromwich insert it? Because he’s a fine writer, thinking of his sentence rhythm and the point he wants to make. The comma does exactly what it should. It makes us pause, breaking the sentence into two parts, each with an interesting point. One is that Wordsworth felt a difficulty others would not have; the other is that he solved it in a distinctive way. It would be easy for readers to glide over this double message, so Bromwich has inserted a speed bump to slow us down. Most of the time, you should follow grammatical rules, like those about commas, but you should bend them when it serves a good purpose. That’s what the writer does here.

The second small point is the phrase “after the revolution” in the first sentence: “Wordsworth turned to poetry after the revolution to remind himself that he was still a human being.” Why doesn’t Bromwich say “after the French Revolution”? Because he has judged his book’s audience. He is writing for specialists who already know which revolution is reverberating through English life in the 1790s. It is the French Revolution, not the earlier loss of the American colonies. If Bromwich were writing for a much broader audience—say, the New York Times Book Review—he would probably insert the extra word to avoid confusion.

The message “Know your audience” applies to all writers. Don’t talk down to them by assuming they can’t get dressed in the morning. Don’t strut around showing off your book learnin’ by tossing in arcane facts and esoteric language for its own sake. Neither will win over readers.

Bromwich, Herbert, and Coleman open their works in different ways, but their choices work well for their different texts. Your task is to decide what kind of opening will work best for yours. Don’t let that happen by default, by grabbing the first idea you happen upon. Consider a couple of different ways of opening your thesis and then choose the one you prefer. Give yourself some options, think them over, then make an informed choice.

Using the Introduction to Map out Your Writing

Whether you begin with a story, puzzle, or broad statement, the next part of the research paper introduction should pose your main questions and establish your argument. This is your thesis statement—your viewpoint along with the supporting reasons and evidence. It should be articulated plainly so readers understand full well what your paper is about and what it will argue.

After that, give your readers a road map of what’s to come. That’s normally done at the end of the introductory section (or, in a book, at the end of the introductory chapter). Here’s John J. Mearsheimer presenting such a road map in The Tragedy of Great Power Politics . He not only tells us the order of upcoming chapters, he explains why he’s chosen that order and which chapters are most important:

The Plan of the Book The rest of the chapters in this book are concerned mainly with answering the six big questions about power which I identified earlier. Chapter 2, which is probably the most important chapter in the book, lays out my theory of why states compete for power and why they pursue hegemony. In Chapters 3 and 4, I define power and explain how to measure it. I do this in order to lay the groundwork for testing my theory… (John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics . New York: W. W. Norton, 2001, p. 27)

As this excerpt makes clear, Mearsheimer has already laid out his “six big questions” in the research paper introduction. Now he’s showing us the path ahead, the path to answering those questions.

At the end of the research paper introduction, give your readers a road map of what’s to come. Tell them what the upcoming sections will be and why they are arranged in this particular order.

Learn how to write an introduction for a research paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

Table of Contents

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1

What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

What is the introduction for a research paper?

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

Why is the introduction important in a research paper?

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

Check out how Peace Alemede uses Paperpal to write her research paper

Peace Alemede, Student, University of Ilorin

Paperpal has been an excellent and beneficial tool for editing my research work. With the help of Paperpal, I am now able to write and produce results at a much faster rate. For instance, I recently used Paperpal to edit a research article that is currently being considered for publication. The tool allowed me to align the language of my paragraph ideas to a more academic setting, thereby saving me both time and resources. As a result, my work was deemed accurate for use. I highly recommend this tool to anyone in need of efficient and effective research paper editing. Peace Alemede, Student, University of Ilorin, Nigeria

Start Writing for Free

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address.

Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

1. Introduce the research topic:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

2. Determine a research niche:

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

3. Place your research within the research niche:

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

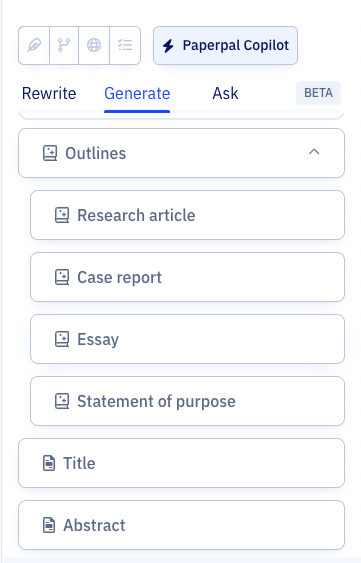

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the purpose of the introduction in research papers.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

How long should the research paper introduction be?

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2

For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

What should be included in the research paper introduction?

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3

Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction.

- Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic.

- Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects.

- Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought.

- Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance.

- Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study

- Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Should I include citations in the introduction for a research paper?

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through.

Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review.

A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

Should I provide a literature review in the research paper introduction?

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following:

- Introduces the topic

- Establishes the study’s significance

- Provides an overview of the relevant literature

- Provides context for the study using literature

- Identifies knowledge gaps

However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction:

- Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research

- Avoid direct quoting

- Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Key points to remember

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

- Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

- Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

- Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

- Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, how to cite in apa format (7th edition):..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples.

Free Introduction to Research Generator

📖 introductions in research.

- ✅ 7 Tips for Introductions

- ⚡ 7 Mistakes to Avoid

🔗 References

Research is crucial in developing new knowledge, solving complex tasks, and gaining headway in various fields. Sometimes, a researcher has the perfect subject to work with and is ready to write about it. However, they realize that they struggle to compose their thoughts and start on their task.

Our research introduction generator is perfect for such occasions.

- Is easy to use,

- Saves time,

- Helps tailor a unique introduction.

The tool might inspire you to take the paper in a new direction. Aside from a user-friendly instrument, we also provide valuable information and advice to make paper writing much easier.

Essay Writing and Introductions

The introduction is the first part of a research paper or an essay in an academic setting . It explains the reason for looking into an issue, its significance, and its goals. With that said, an introduction doesn't cover the study methods or the results of the study. There are separate paper sections to expand on this information in great detail.

A good intro begins with a general statement and narrows it down to the selected research subject. It provides used sources and is usually no longer than four paragraphs. However, the size of the introduction may vary depending on the style guide and research topic . It differs from one field to another, which our introduction in research generator is designed to accommodate.

How to Structure an Intro Paragraph

The introduction gives a concise overview of your research. Important background information makes it easier for the audience to comprehend the significance of your work . Understanding the proper structure of the introduction is vital to get your point across in a straightforward manner.

A well-made intro consists of three elements :

| ✏️ Hook sentence | An introduction starts with a that captivates the reader. It either makes or breaks any incentive to continue with the paper. Researchers should take extra time and effort to perfect the hook sentence. It will serve as an appetizer to the research they've poured their heart into. |

| 🔎️ Background research overview | After the hook sentence, one should briefly explain the . You must talk about the previous studies on the issue that will be further addressed in the paper. It gives readers a taste of what's to come later in the article. |

| 📝 Strong thesis statement | A good introduction ends with a thesis statement anchoring the entire research paper. It explains the main argument for which you'll build a case in one or two sentences. |

✅ 7 Tips for Successful Research Paper Introductions

This section covers the most effective tips for improving your introduction. Several things play into its success:

- Start with the general and narrow it down . The first paragraph briefly covers the broader research field and moves to a particular subject. This approach makes the paper easier to understand for the wider audience .

- Explain the importance and objectives . One should clearly state their aims with a particular research topic. Otherwise, the readers won't understand why they should care about its outcome.

- Use the right amount of citations . The introduction should be based on the latest related data. Do not overuse quotations , as they distract readers from the paper itself.

- Provide a clear-cut research question or hypothesis . The former works best for papers on formal sciences and exploratory research. You may use the later format for empirical scientific research.

- Provide an overview of the paper when possible . The last part of the introduction may include a rundown of the document's structure. Note that its addition varies from one discipline to another. It's more prevalent in papers on technology and less so in medical research.

- Keep it short . The introduction part should be around 500-1000 words. Check the guidelines or ask your professors to better pinpoint the right length for your intro.

- Don't provide too much detail . Avoid mentioning too many specifics in the introductory part. There will be dedicated sections of the paper disclosing them later on. Better use general statements and exclude lengthy explanations.

⚡ 7 Mistakes to Avoid When Writing an Intro

Introductions are often considered to be the most difficult part of writing an essay – perhaps, even more difficult than conclusions! This is why we've also prepared a list of common mistakes you better avoid when working on them.

When writing an introduction, try to avoid...

| ❌ | . Sometimes researchers include data unrelated to the subject of their work. It wastes their time and makes the introductory part harder to structure. |

| ❌ | . As mentioned before, this paper segment should state the article's aim in general terms. If you explain everything at the beginning, there's no reason to write the rest of the document. |

| ❌ | . Sometimes the introduction fails to convince readers about the importance of the work in concrete terms. Make sure to concentrate on the value your work will bring to your field. |

| ❌ | . This tells the readers that the writer doesn't have a fair grasp of the subject. Weigh each piece of information and stick only to relevant facts. |

| ❌ | . The entire paper has to be original. Our handy research introduction generator will help ensure that your writing is unique and effective. |

| ❌ | . A good introduction should clearly state the importance of the study you've decided to investigate. One may achieve this by hinting at the broader . |

| ❌ | . As with all writing, the introductory part needs to be structured efficiently. When sentences feel out of place, it makes readers less likely to continue reading your paper. |

Our research introduction generator will help deal with your writer's block and be beneficial in later work! Remember to give our FAQ a look.

❓ Research Introduction Generator - FAQ

Updated: Jul 19th, 2024

- Introduction to Research. – Richard F. Taflinger, Washington State University

- Introduction Sections in Scientific Research Reports. – George Mason University

- How to Write a Good Introduction in 3 Steps (With Example). – Indeed

- The Role of an Introduction. – Pomona College

- 5 Things to Avoid When Writing an Introduction. – Walden University

- Introduction to Research. – Michigan Technological University

- Introductions and Conclusions. – Leora Freedman and Jerry Plotnick, University of Toronto

- Avoid these three mistakes when writing your introduction. – David Otey, Speaking of Solutions

- Organizing Academic Research Papers: The Introduction. – Sacred Heart University Library

- Introductions. – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers