Directional Hypothesis: Definition and 10 Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

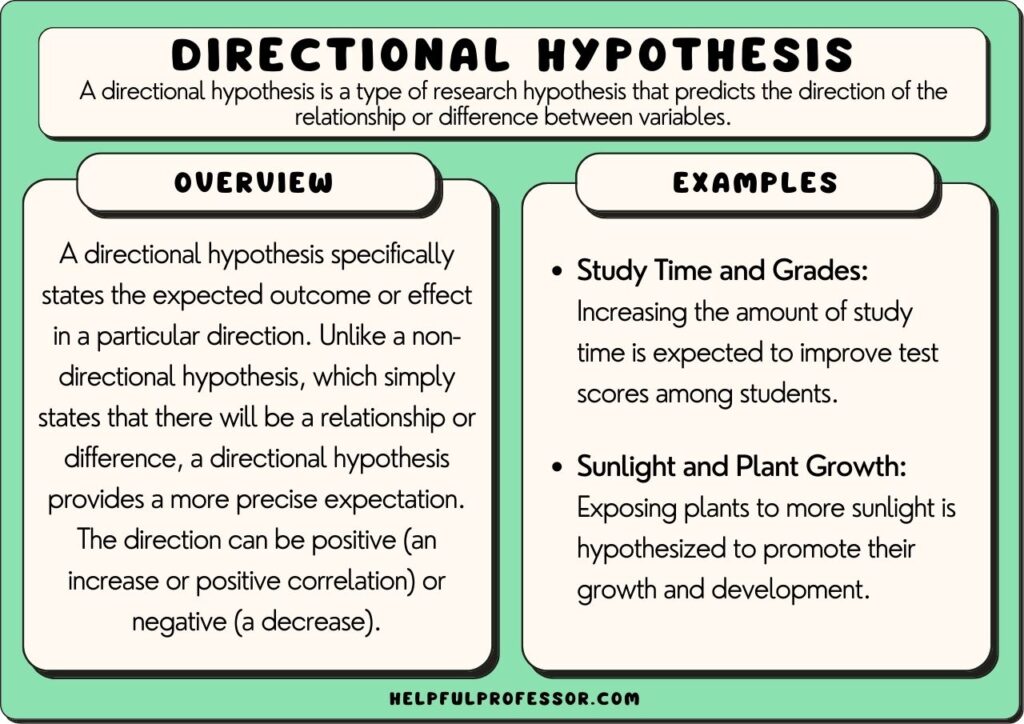

A directional hypothesis refers to a type of hypothesis used in statistical testing that predicts a particular direction of the expected relationship between two variables.

In simpler terms, a directional hypothesis is an educated, specific guess about the direction of an outcome—whether an increase, decrease, or a proclaimed difference in variable sets.

For example, in a study investigating the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance, a directional hypothesis might state that as sleep deprivation (Independent Variable) increases, cognitive performance (Dependent Variable) decreases (Killgore, 2010). Such a hypothesis offers a clear, directional relationship whereby a specific increase or decrease is anticipated.

Global warming provides another notable example of a directional hypothesis. A researcher might hypothesize that as carbon dioxide (CO2) levels increase, global temperatures also increase (Thompson, 2010). In this instance, the hypothesis clearly articulates an upward trend for both variables.

In any given circumstance, it’s imperative that a directional hypothesis is grounded on solid evidence. For instance, the CO2 and global temperature relationship is based on substantial scientific evidence, and not on a random guess or mere speculation (Florides & Christodoulides, 2009).

Directional vs Non-Directional vs Null Hypotheses

A directional hypothesis is generally contrasted to a non-directional hypothesis. Here’s how they compare:

- Directional hypothesis: A directional hypothesis provides a perspective of the expected relationship between variables, predicting the direction of that relationship (either positive, negative, or a specific difference).

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis denotes the possibility of a relationship between two variables ( the independent and dependent variables ), although this hypothesis does not venture a prediction as to the direction of this relationship (Ali & Bhaskar, 2016). For example, a non-directional hypothesis might state that there exists a relationship between a person’s diet (independent variable) and their mood (dependent variable), without indicating whether improvement in diet enhances mood positively or negatively. Overall, the choice between a directional or non-directional hypothesis depends on the known or anticipated link between the variables under consideration in research studies.

Another very important type of hypothesis that we need to know about is a null hypothesis :

- Null hypothesis : The null hypothesis stands as a universality—the hypothesis that there is no observed effect in the population under study, meaning there is no association between variables (or that the differences are down to chance). For instance, a null hypothesis could be constructed around the idea that changing diet (independent variable) has no discernible effect on a person’s mood (dependent variable) (Yan & Su, 2016). This proposition is the one that we aim to disprove in an experiment.

While directional and non-directional hypotheses involve some integrated expectations about the outcomes (either distinct direction or a vague relationship), a null hypothesis operates on the premise of negating such relationships or effects.

The null hypotheses is typically proposed to be negated or disproved by statistical tests, paving way for the acceptance of an alternate hypothesis (either directional or non-directional).

Directional Hypothesis Examples

1. exercise and heart health.

Research suggests that as regular physical exercise (independent variable) increases, the risk of heart disease (dependent variable) decreases (Jakicic, Davis, Rogers, King, Marcus, Helsel, Rickman, Wahed, Belle, 2016). In this example, a directional hypothesis anticipates that the more individuals maintain routine workouts, the lesser would be their odds of developing heart-related disorders. This assumption is based on the underlying fact that routine exercise can help reduce harmful cholesterol levels, regulate blood pressure, and bring about overall health benefits. Thus, a direction – a decrease in heart disease – is expected in relation with an increase in exercise.

2. Screen Time and Sleep Quality

Another classic instance of a directional hypothesis can be seen in the relationship between the independent variable, screen time (especially before bed), and the dependent variable, sleep quality. This hypothesis predicts that as screen time before bed increases, sleep quality decreases (Chang, Aeschbach, Duffy, Czeisler, 2015). The reasoning behind this hypothesis is the disruptive effect of artificial light (especially blue light from screens) on melatonin production, a hormone needed to regulate sleep. As individuals spend more time exposed to screens before bed, it is predictably hypothesized that their sleep quality worsens.

3. Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover

A typical scenario in organizational behavior research posits that as job satisfaction (independent variable) increases, the rate of employee turnover (dependent variable) decreases (Cheng, Jiang, & Riley, 2017). This directional hypothesis emphasizes that an increased level of job satisfaction would lead to a reduced rate of employees leaving the company. The theoretical basis for this hypothesis is that satisfied employees often tend to be more committed to the organization and are less likely to seek employment elsewhere, thus reducing turnover rates.

4. Healthy Eating and Body Weight

Healthy eating, as the independent variable, is commonly thought to influence body weight, the dependent variable, in a positive way. For example, the hypothesis might state that as consumption of healthy foods increases, an individual’s body weight decreases (Framson, Kristal, Schenk, Littman, Zeliadt, & Benitez, 2009). This projection is based on the premise that healthier foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are generally lower in calories than junk food, assisting in weight management.

5. Sun Exposure and Skin Health

The association between sun exposure (independent variable) and skin health (dependent variable) allows for a definitive hypothesis declaring that as sun exposure increases, the risk of skin damage or skin cancer increases (Whiteman, Whiteman, & Green, 2001). The premise aligns with the understanding that overexposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays can deteriorate skin health, leading to conditions like sunburn or, in extreme cases, skin cancer.

6. Study Hours and Academic Performance

A regularly assessed relationship in academia suggests that as the number of study hours (independent variable) rises, so too does academic performance (dependent variable) (Nonis, Hudson, Logan, Ford, 2013). The hypothesis proposes a positive correlation , with an increase in study time expected to contribute to enhanced academic outcomes.

7. Screen Time and Eye Strain

It’s commonly hypothesized that as screen time (independent variable) increases, the likelihood of experiencing eye strain (dependent variable) also increases (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018). This is based on the idea that prolonged engagement with digital screens—computers, tablets, or mobile phones—can cause discomfort or fatigue in the eyes, attributing to symptoms of eye strain.

8. Physical Activity and Stress Levels

In the sphere of mental health, it’s often proposed that as physical activity (independent variable) increases, levels of stress (dependent variable) decrease (Stonerock, Hoffman, Smith, Blumenthal, 2015). Regular exercise is known to stimulate the production of endorphins, the body’s natural mood elevators, helping to alleviate stress.

9. Water Consumption and Kidney Health

A common health-related hypothesis might predict that as water consumption (independent variable) increases, the risk of kidney stones (dependent variable) decreases (Curhan, Willett, Knight, & Stampfer, 2004). Here, an increase in water intake is inferred to reduce the risk of kidney stones by diluting the substances that lead to stone formation.

10. Traffic Noise and Sleep Quality

In urban planning research, it’s often supposed that as traffic noise (independent variable) increases, sleep quality (dependent variable) decreases (Muzet, 2007). Increased noise levels, particularly during the night, can result in sleep disruptions, thus, leading to poor sleep quality.

11. Sugar Consumption and Dental Health

In the field of dental health, an example might be stating as one’s sugar consumption (independent variable) increases, dental health (dependent variable) decreases (Sheiham, & James, 2014). This stems from the fact that sugar is a major factor in tooth decay, and increased consumption of sugary foods or drinks leads to a decline in dental health due to the high likelihood of cavities.

See 15 More Examples of Hypotheses Here

A directional hypothesis plays a critical role in research, paving the way for specific predicted outcomes based on the relationship between two variables. These hypotheses clearly illuminate the expected direction—the increase or decrease—of an effect. From predicting the impacts of healthy eating on body weight to forecasting the influence of screen time on sleep quality, directional hypotheses allow for targeted and strategic examination of phenomena. In essence, directional hypotheses provide the crucial path for inquiry, shaping the trajectory of research studies and ultimately aiding in the generation of insightful, relevant findings.

Ali, S., & Bhaskar, S. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 662-669. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0019-5049.190623

Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (4), 1232-1237. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418490112

Cheng, G. H. L., Jiang, D., & Riley, J. H. (2017). Organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation of regular and contractual primary school teachers in China. New Psychology, 19 (3), 316-326. Doi: https://doi.org/10.4103%2F2249-4863.184631

Curhan, G. C., Willett, W. C., Knight, E. L., & Stampfer, M. J. (2004). Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in younger women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164 (8), 885–891.

Florides, G. A., & Christodoulides, P. (2009). Global warming and carbon dioxide through sciences. Environment international , 35 (2), 390-401. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.07.007

Framson, C., Kristal, A. R., Schenk, J. M., Littman, A. J., Zeliadt, S., & Benitez, D. (2009). Development and validation of the mindful eating questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109 (8), 1439-1444. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.006

Jakicic, J. M., Davis, K. K., Rogers, R. J., King, W. C., Marcus, M. D., Helsel, D., … & Belle, S. H. (2016). Effect of wearable technology combined with a lifestyle intervention on long-term weight loss: The IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316 (11), 1161-1171.

Khan, S., & Iqbal, N. (2013). Study of the relationship between study habits and academic achievement of students: A case of SPSS model. Higher Education Studies, 3 (1), 14-26.

Killgore, W. D. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in brain research , 185 , 105-129. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00007-5

Marczinski, C. A., & Fillmore, M. T. (2014). Dissociative antagonistic effects of caffeine on alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22 (4), 298–311. doi: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.228

Muzet, A. (2007). Environmental Noise, Sleep and Health. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11 (2), 135-142. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.001

Nonis, S. A., Hudson, G. I., Logan, L. B., & Ford, C. W. (2013). Influence of perceived control over time on college students’ stress and stress-related outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 54 (5), 536-552. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018753706925

Sheiham, A., & James, W. P. (2014). A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public health nutrition, 17 (10), 2176-2184. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001400113X

Sheppard, A. L., & Wolffsohn, J. S. (2018). Digital eye strain: prevalence, measurement and amelioration. BMJ open ophthalmology , 3 (1), e000146. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2018-000146

Stonerock, G. L., Hoffman, B. M., Smith, P. J., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2015). Exercise as Treatment for Anxiety: Systematic Review and Analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49 (4), 542–556. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9685-9

Thompson, L. G. (2010). Climate change: The evidence and our options. The Behavior Analyst , 33 , 153-170. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392211

Whiteman, D. C., Whiteman, C. A., & Green, A. C. (2001). Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes & Control, 12 (1), 69-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008980919928

Yan, X., & Su, X. (2009). Linear regression analysis: theory and computing . New Jersey: World Scientific.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

psychologyrocks

Hypotheses; directional and non-directional, what is the difference between an experimental and an alternative hypothesis.

Nothing much! If the study is a true experiment then we can call the hypothesis “an experimental hypothesis”, a prediction is made about how the IV causes an effect on the DV. In a study which does not involve the direct manipulation of an IV, i.e. a natural or quasi-experiment or any other quantitative research method (e.g. survey) has been used, then we call it an “alternative hypothesis”, it is the alternative to the null.

Directional hypothesis: A directional (or one-tailed hypothesis) states which way you think the results are going to go, for example in an experimental study we might say…”Participants who have been deprived of sleep for 24 hours will have more cold symptoms the week after exposure to a virus than participants who have not been sleep deprived”; the hypothesis compares the two groups/conditions and states which one will ….have more/less, be quicker/slower, etc.

If we had a correlational study, the directional hypothesis would state whether we expect a positive or a negative correlation, we are stating how the two variables will be related to each other, e.g. there will be a positive correlation between the number of stressful life events experienced in the last year and the number of coughs and colds suffered, whereby the more life events you have suffered the more coughs and cold you will have had”. The directional hypothesis can also state a negative correlation, e.g. the higher the number of face-book friends, the lower the life satisfaction score “

Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional (or two tailed hypothesis) simply states that there will be a difference between the two groups/conditions but does not say which will be greater/smaller, quicker/slower etc. Using our example above we would say “There will be a difference between the number of cold symptoms experienced in the following week after exposure to a virus for those participants who have been sleep deprived for 24 hours compared with those who have not been sleep deprived for 24 hours.”

When the study is correlational, we simply state that variables will be correlated but do not state whether the relationship will be positive or negative, e.g. there will be a significant correlation between variable A and variable B.

Null hypothesis The null hypothesis states that the alternative or experimental hypothesis is NOT the case, if your experimental hypothesis was directional you would say…

Participants who have been deprived of sleep for 24 hours will NOT have more cold symptoms in the following week after exposure to a virus than participants who have not been sleep deprived and any difference that does arise will be due to chance alone.

or with a directional correlational hypothesis….

There will NOT be a positive correlation between the number of stress life events experienced in the last year and the number of coughs and colds suffered, whereby the more life events you have suffered the more coughs and cold you will have had”

With a non-directional or two tailed hypothesis…

There will be NO difference between the number of cold symptoms experienced in the following week after exposure to a virus for those participants who have been sleep deprived for 24 hours compared with those who have not been sleep deprived for 24 hours.

or for a correlational …

there will be NO correlation between variable A and variable B.

When it comes to conducting an inferential stats test, if you have a directional hypothesis , you must do a one tailed test to find out whether your observed value is significant. If you have a non-directional hypothesis , you must do a two tailed test .

Exam Techniques/Advice

- Remember, a decent hypothesis will contain two variables, in the case of an experimental hypothesis there will be an IV and a DV; in a correlational hypothesis there will be two co-variables

- both variables need to be fully operationalised to score the marks, that is you need to be very clear and specific about what you mean by your IV and your DV; if someone wanted to repeat your study, they should be able to look at your hypothesis and know exactly what to change between the two groups/conditions and exactly what to measure (including any units/explanation of rating scales etc, e.g. “where 1 is low and 7 is high”)

- double check the question, did it ask for a directional or non-directional hypothesis?

- if you were asked for a null hypothesis, make sure you always include the phrase “and any difference/correlation (is your study experimental or correlational?) that does arise will be due to chance alone”

Practice Questions:

- Mr Faraz wants to compare the levels of attendance between his psychology group and those of Mr Simon, who teaches a different psychology group. Which of the following is a suitable directional (one tailed) hypothesis for Mr Faraz’s investigation?

A There will be a difference in the levels of attendance between the two psychology groups.

B Students’ level of attendance will be higher in Mr Faraz’s group than Mr Simon’s group.

C Any difference in the levels of attendance between the two psychology groups is due to chance.

D The level of attendance of the students will depend upon who is teaching the groups.

2. Tracy works for the local council. The council is thinking about reducing the number of people it employs to pick up litter from the street. Tracy has been asked to carry out a study to see if having the streets cleaned at less regular intervals will affect the amount of litter the public will drop. She studies a street to compare how much litter is dropped at two different times, once when it has just been cleaned and once after it has not been cleaned for a month.

Write a fully operationalised non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis for Tracy’s study. (2)

3. Jamila is conducting a practical investigation to look at gender differences in carrying out visuo-spatial tasks. She decides to give males and females a jigsaw puzzle and will time them to see who completes it the fastest. She uses a random sample of pupils from a local school to get her participants.

(a) Write a fully operationalised directional (one tailed) hypothesis for Jamila’s study. (2) (b) Outline one strength and one weakness of the random sampling method. You may refer to Jamila’s use of this type of sampling in your answer. (4)

4. Which of the following is a non-directional (two tailed) hypothesis?

A There is a difference in driving ability with men being better drivers than women

B Women are better at concentrating on more than one thing at a time than men

C Women spend more time doing the cooking and cleaning than men

D There is a difference in the number of men and women who participate in sports

Revision Activities

writing-hypotheses-revision-sheet

Quizizz link for teachers: https://quizizz.com/admin/quiz/5bf03f51add785001bc5a09e

By Psychstix by Mandy wood

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

What is a Directional Hypothesis? (Definition & Examples)

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter . For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

Whenever we perform a hypothesis test, we always write down a null and alternative hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ): The sample data occurs purely from chance.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ): The sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

A hypothesis test can either contain a directional hypothesis or a non-directional hypothesis:

- Directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the less than (“”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is a positive or negative effect.

- Non-directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the not equal (“≠”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is some effect, without specifying the direction of the effect.

Note that directional hypothesis tests are also called “one-tailed” tests and non-directional hypothesis tests are also called “two-tailed” tests.

Check out the following examples to gain a better understanding of directional vs. non-directional hypothesis tests.

Example 1: Baseball Programs

A baseball coach believes a certain 4-week program will increase the mean hitting percentage of his players, which is currently 0.285.

To test this, he measures the hitting percentage of each of his players before and after participating in the program.

He then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = .285 (the program will have no effect on the mean hitting percentage)

- H A : μ > .285 (the program will cause mean hitting percentage to increase)

This is an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the greater than “>” sign. The coach believes that the program will influence the mean hitting percentage of his players in a positive direction.

Example 2: Plant Growth

A biologist believes that a certain pesticide will cause plants to grow less during a one-month period than they normally do, which is currently 10 inches.

To test this, she applies the pesticide to each of the plants in her laboratory for one month.

She then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = 10 inches (the pesticide will have no effect on the mean plant growth)

This is also an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the less than “negative direction.

Example 3: Studying Technique

A professor believes that a certain studying technique will influence the mean score that her students receive on a certain exam, but she’s unsure if it will increase or decrease the mean score, which is currently 82.

To test this, she lets each student use the studying technique for one month leading up to the exam and then administers the same exam to each of the students.

- H 0 : μ = 82 (the studying technique will have no effect on the mean exam score)

- H A : μ ≠ 82 (the studying technique will cause the mean exam score to be different than 82)

This is an example of a non-directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the not equal “≠” sign. The professor believes that the studying technique will influence the mean exam score, but doesn’t specify whether it will cause the mean score to increase or decrease.

Additional Resources

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test

How to Perform a Partial F-Test in Excel

4 examples of confidence intervals in real life, related posts, how to normalize data between -1 and 1, vba: how to check if string contains another..., how to interpret f-values in a two-way anova, how to create a vector of ones in..., how to determine if a probability distribution is..., what is a symmetric histogram (definition & examples), how to find the mode of a histogram..., how to find quartiles in even and odd..., how to calculate sxy in statistics (with example), how to calculate sxx in statistics (with example).

Directional Hypothesis

Definition:

A directional hypothesis is a specific type of hypothesis statement in which the researcher predicts the direction or effect of the relationship between two variables.

Key Features

1. Predicts direction:

Unlike a non-directional hypothesis, which simply states that there is a relationship between two variables, a directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction of the relationship.

2. Involves one-tailed test:

Directional hypotheses typically require a one-tailed statistical test, as they are concerned with whether the relationship is positive or negative, rather than simply whether a relationship exists.

3. Example:

An example of a directional hypothesis would be: “Increasing levels of exercise will result in greater weight loss.”

4. Researcher’s prior belief:

A directional hypothesis is often formed based on the researcher’s prior knowledge, theoretical understanding, or previous empirical evidence relating to the variables under investigation.

5. Confirmatory nature:

Directional hypotheses are considered confirmatory, as they provide a specific prediction that can be tested statistically, allowing researchers to either support or reject the hypothesis.

6. Advantages and disadvantages:

Directional hypotheses help focus the research by explicitly stating the expected relationship, but they can also limit exploration of alternative explanations or unexpected findings.

Directional and non-directional hypothesis: A Comprehensive Guide

Karolina Konopka

Customer support manager

Want to talk with us?

In the world of research and statistical analysis, hypotheses play a crucial role in formulating and testing scientific claims. Understanding the differences between directional and non-directional hypothesis is essential for designing sound experiments and drawing accurate conclusions. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or simply curious about the foundations of hypothesis testing, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools to navigate this fundamental aspect of scientific inquiry.

Understanding Directional Hypothesis

Understanding directional hypotheses is crucial for conducting hypothesis-driven research, as they guide the selection of appropriate statistical tests and aid in the interpretation of results. By incorporating directional hypotheses, researchers can make more precise predictions, contribute to scientific knowledge, and advance their fields of study.

Definition of directional hypothesis

Directional hypotheses, also known as one-tailed hypotheses, are statements in research that make specific predictions about the direction of a relationship or difference between variables. Unlike non-directional hypotheses, which simply state that there is a relationship or difference without specifying its direction, directional hypotheses provide a focused and precise expectation.

A directional hypothesis predicts either a positive or negative relationship between variables or predicts that one group will perform better than another. It asserts a specific direction of effect or outcome. For example, a directional hypothesis could state that “increased exposure to sunlight will lead to an improvement in mood” or “participants who receive the experimental treatment will exhibit higher levels of cognitive performance compared to the control group.”

Directional hypotheses are formulated based on existing theory, prior research, or logical reasoning, and they guide the researcher’s expectations and analysis. They allow for more targeted predictions and enable researchers to test specific hypotheses using appropriate statistical tests.

The role of directional hypothesis in research

Directional hypotheses also play a significant role in research surveys. Let’s explore their role specifically in the context of survey research:

- Objective-driven surveys : Directional hypotheses help align survey research with specific objectives. By formulating directional hypotheses, researchers can focus on gathering data that directly addresses the predicted relationship or difference between variables of interest.

- Question design and measurement : Directional hypotheses guide the design of survey question types and the selection of appropriate measurement scales. They ensure that the questions are tailored to capture the specific aspects related to the predicted direction, enabling researchers to obtain more targeted and relevant data from survey respondents.

- Data analysis and interpretation : Directional hypotheses assist in data analysis by directing researchers towards appropriate statistical tests and methods. Researchers can analyze the survey data to specifically test the predicted relationship or difference, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of their findings. The results can then be interpreted within the context of the directional hypothesis, providing more meaningful insights.

- Practical implications and decision-making : Directional hypotheses in surveys often have practical implications. When the predicted relationship or difference is confirmed, it informs decision-making processes, program development, or interventions. The survey findings based on directional hypotheses can guide organizations, policymakers, or practitioners in making informed choices to achieve desired outcomes.

- Replication and further research : Directional hypotheses in survey research contribute to the replication and extension of studies. Researchers can replicate the survey with different populations or contexts to assess the generalizability of the predicted relationships. Furthermore, if the directional hypothesis is supported, it encourages further research to explore underlying mechanisms or boundary conditions.

By incorporating directional hypotheses in survey research, researchers can align their objectives, design effective surveys, conduct focused data analysis, and derive practical insights. They provide a framework for organizing survey research and contribute to the accumulation of knowledge in the field.

Examples of research questions for directional hypothesis

Here are some examples of research questions that lend themselves to directional hypotheses:

- Does increased daily exercise lead to a decrease in body weight among sedentary adults?

- Is there a positive relationship between study hours and academic performance among college students?

- Does exposure to violent video games result in an increase in aggressive behavior among adolescents?

- Does the implementation of a mindfulness-based intervention lead to a reduction in stress levels among working professionals?

- Is there a difference in customer satisfaction between Product A and Product B, with Product A expected to have higher satisfaction ratings?

- Does the use of social media influence self-esteem levels, with higher social media usage associated with lower self-esteem?

- Is there a negative relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover, indicating that lower job satisfaction leads to higher turnover rates?

- Does the administration of a specific medication result in a decrease in symptoms among individuals with a particular medical condition?

- Does increased access to early childhood education lead to improved cognitive development in preschool-aged children?

- Is there a difference in purchase intention between advertisements with celebrity endorsements and advertisements without, with celebrity endorsements expected to have a higher impact?

These research questions generate specific predictions about the direction of the relationship or difference between variables and can be tested using appropriate research methods and statistical analyses.

Definition of non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses, also known as two-tailed hypotheses, are statements in research that indicate the presence of a relationship or difference between variables without specifying the direction of the effect. Instead of making predictions about the specific direction of the relationship or difference, non-directional hypotheses simply state that there is an association or distinction between the variables of interest.

Non-directional hypotheses are often used when there is no prior theoretical basis or clear expectation about the direction of the relationship. They leave the possibility open for either a positive or negative relationship, or for both groups to differ in some way without specifying which group will perform better or worse.

Advantages and utility of non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses in survey s offer several advantages and utilities, providing flexibility and comprehensive analysis of survey data. Here are some of the key advantages and utilities of using non-directional hypotheses in surveys:

- Exploration of Relationships : Non-directional hypotheses allow researchers to explore and examine relationships between variables without assuming a specific direction. This is particularly useful in surveys where the relationship between variables may not be well-known or there may be conflicting evidence regarding the direction of the effect.

- Flexibility in Question Design : With non-directional hypotheses, survey questions can be designed to measure the relationship between variables without being biased towards a particular outcome. This flexibility allows researchers to collect data and analyze the results more objectively.

- Open to Unexpected Findings : Non-directional hypotheses enable researchers to be open to unexpected or surprising findings in survey data. By not committing to a specific direction of the effect, researchers can identify and explore relationships that may not have been initially anticipated, leading to new insights and discoveries.

- Comprehensive Analysis : Non-directional hypotheses promote comprehensive analysis of survey data by considering the possibility of an effect in either direction. Researchers can assess the magnitude and significance of relationships without limiting their analysis to only one possible outcome.

- S tatistical Validity : Non-directional hypotheses in surveys allow for the use of two-tailed statistical tests, which provide a more conservative and robust assessment of significance. Two-tailed tests consider both positive and negative deviations from the null hypothesis, ensuring accurate and reliable statistical analysis of survey data.

- Exploratory Research : Non-directional hypotheses are particularly useful in exploratory research, where the goal is to gather initial insights and generate hypotheses. Surveys with non-directional hypotheses can help researchers explore various relationships and identify patterns that can guide further research or hypothesis development.

It is worth noting that the choice between directional and non-directional hypotheses in surveys depends on the research objectives, existing knowledge, and the specific variables being investigated. Researchers should carefully consider the advantages and limitations of each approach and select the one that aligns best with their research goals and survey design.

- Share with others

- Twitter Twitter Icon

- LinkedIn LinkedIn Icon

Related posts

Popup surveys: definition, types, and examples, mastering matrix questions: the complete guide + one special technique, microsurveys: complete guide, recurring surveys: the ultimate guide, close-ended questions: definition, types, and examples, top 10 typeform alternatives and competitors, get answers today.

- No credit card required

- No time limit on Free plan

You can modify this template in every possible way.

All templates work great on every device.

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a one-tailed hypothesis that states the direction of the difference or relationship (e.g. boys are more helpful than girls).

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Research Methods: MCQ Revision Test 1 for AQA A Level Psychology

Topic Videos

Example Answers for Research Methods: A Level Psychology, Paper 2, June 2018 (AQA)

Exam Support

Example Answer for Question 14 Paper 2: AS Psychology, June 2017 (AQA)

Model answer for question 11 paper 2: as psychology, june 2016 (aqa), a level psychology topic quiz - research methods.

Quizzes & Activities

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Crit Care Med

- v.23(Suppl 3); 2019 Sep

An Introduction to Statistics: Understanding Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Errors

Priya ranganathan.

1 Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

The second article in this series on biostatistics covers the concepts of sample, population, research hypotheses and statistical errors.

How to cite this article

Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS. An Introduction to Statistics: Understanding Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Errors. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(Suppl 3):S230–S231.

Two papers quoted in this issue of the Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine report. The results of studies aim to prove that a new intervention is better than (superior to) an existing treatment. In the ABLE study, the investigators wanted to show that transfusion of fresh red blood cells would be superior to standard-issue red cells in reducing 90-day mortality in ICU patients. 1 The PROPPR study was designed to prove that transfusion of a lower ratio of plasma and platelets to red cells would be superior to a higher ratio in decreasing 24-hour and 30-day mortality in critically ill patients. 2 These studies are known as superiority studies (as opposed to noninferiority or equivalence studies which will be discussed in a subsequent article).

SAMPLE VERSUS POPULATION

A sample represents a group of participants selected from the entire population. Since studies cannot be carried out on entire populations, researchers choose samples, which are representative of the population. This is similar to walking into a grocery store and examining a few grains of rice or wheat before purchasing an entire bag; we assume that the few grains that we select (the sample) are representative of the entire sack of grains (the population).

The results of the study are then extrapolated to generate inferences about the population. We do this using a process known as hypothesis testing. This means that the results of the study may not always be identical to the results we would expect to find in the population; i.e., there is the possibility that the study results may be erroneous.

HYPOTHESIS TESTING

A clinical trial begins with an assumption or belief, and then proceeds to either prove or disprove this assumption. In statistical terms, this belief or assumption is known as a hypothesis. Counterintuitively, what the researcher believes in (or is trying to prove) is called the “alternate” hypothesis, and the opposite is called the “null” hypothesis; every study has a null hypothesis and an alternate hypothesis. For superiority studies, the alternate hypothesis states that one treatment (usually the new or experimental treatment) is superior to the other; the null hypothesis states that there is no difference between the treatments (the treatments are equal). For example, in the ABLE study, we start by stating the null hypothesis—there is no difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs. We then state the alternate hypothesis—There is a difference between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs. It is important to note that we have stated that the groups are different, without specifying which group will be better than the other. This is known as a two-tailed hypothesis and it allows us to test for superiority on either side (using a two-sided test). This is because, when we start a study, we are not 100% certain that the new treatment can only be better than the standard treatment—it could be worse, and if it is so, the study should pick it up as well. One tailed hypothesis and one-sided statistical testing is done for non-inferiority studies, which will be discussed in a subsequent paper in this series.

STATISTICAL ERRORS

There are two possibilities to consider when interpreting the results of a superiority study. The first possibility is that there is truly no difference between the treatments but the study finds that they are different. This is called a Type-1 error or false-positive error or alpha error. This means falsely rejecting the null hypothesis.

The second possibility is that there is a difference between the treatments and the study does not pick up this difference. This is called a Type 2 error or false-negative error or beta error. This means falsely accepting the null hypothesis.

The power of the study is the ability to detect a difference between groups and is the converse of the beta error; i.e., power = 1-beta error. Alpha and beta errors are finalized when the protocol is written and form the basis for sample size calculation for the study. In an ideal world, we would not like any error in the results of our study; however, we would need to do the study in the entire population (infinite sample size) to be able to get a 0% alpha and beta error. These two errors enable us to do studies with realistic sample sizes, with the compromise that there is a small possibility that the results may not always reflect the truth. The basis for this will be discussed in a subsequent paper in this series dealing with sample size calculation.

Conventionally, type 1 or alpha error is set at 5%. This means, that at the end of the study, if there is a difference between groups, we want to be 95% certain that this is a true difference and allow only a 5% probability that this difference has occurred by chance (false positive). Type 2 or beta error is usually set between 10% and 20%; therefore, the power of the study is 90% or 80%. This means that if there is a difference between groups, we want to be 80% (or 90%) certain that the study will detect that difference. For example, in the ABLE study, sample size was calculated with a type 1 error of 5% (two-sided) and power of 90% (type 2 error of 10%) (1).

Table 1 gives a summary of the two types of statistical errors with an example

Statistical errors

| (a) Types of statistical errors | |||

| : Null hypothesis is | |||

| True | False | ||

| Null hypothesis is actually | True | Correct results! | Falsely rejecting null hypothesis - Type I error |

| False | Falsely accepting null hypothesis - Type II error | Correct results! | |

| (b) Possible statistical errors in the ABLE trial | |||

| There is difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | There difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | ||

| Truth | There is difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | Correct results! | Falsely rejecting null hypothesis - Type I error |

| There difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | Falsely accepting null hypothesis - Type II error | Correct results! | |

In the next article in this series, we will look at the meaning and interpretation of ‘ p ’ value and confidence intervals for hypothesis testing.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

Directional Hypothesis Statement

Ai generator.

Grasping the intricacies of a directional hypothesis is a stepping stone in advanced research. It offers a clear perspective, pointing towards a specific prediction. From meticulously crafted examples to a thesis statement writing guide, and invaluable tips – this segment shines a light on the essence of formulating a precise and informed directional hypothesis. Embark on this enlightening journey and amplify the quality and clarity of your research endeavors.

What is a Directional hypothesis?

A directional hypothesis, often referred to as a one-tailed hypothesis , is a specific type of hypothesis that predicts the direction of the expected relationship between variables. This type of hypothesis is used when researchers have enough preliminary evidence or theoretical foundation to predict the direction of the relationship, rather than merely stating that a relationship exists.

For example, based on previous studies or established theories, a researcher might hypothesize that a specific intervention will lead to an increase (or decrease) in a certain outcome, rather than just hypothesizing that the intervention will have some effect without specifying the direction of that effect.

What is an example of a Directional hypothesis Statement?

“Children exposed to interactive educational software will demonstrate a higher increase in mathematical skills compared to children who receive traditional classroom instruction.” In this statement, the direction of the expected relationship is clear – the use of interactive educational software is predicted to have a positive effect on mathematical skills. You may also be interested in our non directional .

100 Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples

Size: 244 KB

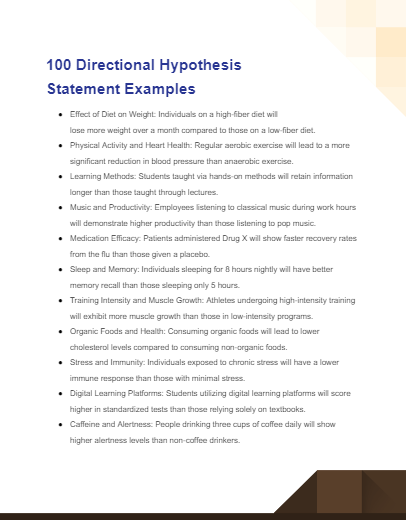

Directional hypotheses are pivotal in streamlining research focus, providing a clear trajectory by anticipating a specific trend or outcome. They’re an embodiment of informed predictions, crafted based on prior knowledge or insightful observations. Discover below a plethora of examples showcasing the essence of these one-tailed, directional assertions.

- Effect of Diet on Weight: Individuals on a high-fiber diet will lose more weight over a month compared to those on a low-fiber diet.

- Physical Activity and Heart Health: Regular aerobic exercise will lead to a more significant reduction in blood pressure than anaerobic exercise.

- Learning Methods: Students taught via hands-on methods will retain information longer than those taught through lectures.

- Music and Productivity: Employees listening to classical music during work hours will demonstrate higher productivity than those listening to pop music.

- Medication Efficacy: Patients administered Drug X will show faster recovery rates from the flu than those given a placebo.

- Sleep and Memory: Individuals sleeping for 8 hours nightly will have better memory recall than those sleeping only 5 hours.

- Training Intensity and Muscle Growth: Athletes undergoing high-intensity training will exhibit more muscle growth than those in low-intensity programs.

- Organic Foods and Health: Consuming organic foods will lead to lower cholesterol levels compared to consuming non-organic foods.

- Stress and Immunity: Individuals exposed to chronic stress will have a lower immune response than those with minimal stress.

- Digital Learning Platforms: Students utilizing digital learning platforms will score higher in standardized tests than those relying solely on textbooks.

- Caffeine and Alertness: People drinking three cups of coffee daily will show higher alertness levels than non-coffee drinkers.

- Therapy Types: Patients undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy will show greater reductions in depressive symptoms than those in talk therapy.

- E-Books and Reading Speed: Individuals reading from e-books will process content faster than those reading traditional paper books.

- Urban Living and Mental Health: Residents in urban areas will report higher stress levels than those living in rural regions.

- UV Exposure and Skin Health: Consistent exposure to UV rays will lead to faster skin aging compared to limited sun exposure.

- Yoga and Flexibility: Engaging in daily yoga practices will increase flexibility more significantly than bi-weekly practices.

- Meditation and Stress Reduction: Practicing daily meditation will lead to a more substantial decrease in cortisol levels than sporadic meditation.

- Parenting Styles and Child Independence: Children raised with authoritative parenting styles will demonstrate higher levels of independence than those raised with permissive styles.

- Economic Incentives: Workers receiving performance-based bonuses will exhibit higher job satisfaction than those with fixed salaries.

- Sugar Intake and Energy: Consuming high sugar foods will lead to a more rapid energy decline than low-sugar foods.

- Language Acquisition: Children exposed to bilingual environments before age five will develop superior linguistic skills compared to those exposed later in life.

- Herbal Teas and Sleep: Drinking chamomile tea before bedtime will result in a better sleep quality compared to drinking green tea.

- Posture and Back Pain: Individuals who practice regular posture exercises will experience less chronic back pain than those who don’t.

- Air Quality and Respiratory Issues: Residents in cities with high air pollution will report more respiratory issues than those in cities with cleaner air.

- Online Marketing and Sales: Businesses employing targeted online advertising strategies will see a higher increase in sales than those using traditional advertising methods.

- Pet Ownership and Loneliness: Seniors who own pets will report lower levels of loneliness than those who don’t have pets.

- Dietary Supplements and Immunity: Regular intake of vitamin C supplements will lead to fewer instances of common cold than a placebo.

- Technology and Social Skills: Children who spend over five hours daily on electronic devices will exhibit weaker face-to-face social skills than those who spend less than an hour.

- Remote Work and Productivity: Employees working remotely will report higher job satisfaction than those working in a traditional office setting.

- Organic Farming and Soil Health: Farms employing organic methods will have richer soil nutrient content than those using conventional methods.

- Probiotics and Digestive Health: Consuming probiotics daily will lead to improved gut health compared to not consuming any.

- Art Therapy and Trauma Recovery: Individuals undergoing art therapy will show faster emotional recovery from trauma than those using only talk therapy.

- Video Games and Reflexes: Regular gamers will demonstrate quicker reflex actions than non-gamers.

- Forest Bathing and Stress: Engaging in monthly forest bathing sessions will reduce stress levels more significantly than urban recreational activities.

- Vegan Diet and Heart Health: Individuals following a vegan diet will have a lower risk of heart diseases compared to those on omnivorous diets.

- Mindfulness and Anxiety: Practicing mindfulness meditation will result in a more significant reduction in anxiety levels than general relaxation techniques.

- Solar Energy and Cost Efficiency: Over a decade, households using solar energy will report more cost savings than those relying on traditional electricity sources.

- Active Commuting and Fitness Level: People who cycle or walk to work will have better cardiovascular health than those who commute by car.

- Online Learning and Retention: Students who engage in interactive online learning will retain subject matter better than those using passive video lectures.

- Gardening and Mental Wellbeing: Engaging in regular gardening activities will lead to improved mental well-being compared to non-gardening related hobbies.

- Music Therapy and Memory: Alzheimer’s patients exposed to regular music therapy sessions will display better memory retention than those who aren’t.

- Organic Foods and Allergies: Individuals consuming primarily organic foods will report fewer food allergies compared to those consuming non-organic foods.

- Class Size and Learning Efficiency: Students in smaller class sizes will demonstrate higher academic achievements than those in larger classes.

- Sports and Leadership Skills: Teenagers engaged in team sports will develop stronger leadership skills than those engaged in solitary activities.

- Virtual Reality and Pain Management: Patients using virtual reality as a distraction method during minor surgical procedures will report lower pain levels than those using traditional methods.

- Recycling and Environmental Awareness: Communities with mandatory recycling programs will demonstrate higher environmental awareness than those without such programs.

- Acupuncture and Migraine Relief: Migraine sufferers receiving regular acupuncture treatments will experience fewer episodes than those relying only on medication.

- Urban Green Spaces and Mental Health: Residents in cities with ample green spaces will show lower rates of depression compared to cities predominantly built-up.

- Aquatic Exercises and Joint Health: Individuals with arthritis participating in aquatic exercises will report greater joint mobility than those who do land-based exercises.

- E-books and Reading Comprehension: Students using e-books for study will demonstrate similar reading comprehension levels as those using traditional textbooks.

- Financial Literacy Programs and Debt Management: Adults who attended financial literacy programs in school will manage their debts more effectively than those who didn’t.

- Play-based Learning and Creativity: Children educated through play-based learning methods will exhibit higher creativity levels than those in a strictly academic environment.

- Caffeine Consumption and Cognitive Function: Moderate daily caffeine consumption will lead to improved cognitive function compared to high or no caffeine intake.

- Vegetable Intake and Skin Health: Individuals consuming a diet rich in colorful vegetables will have healthier skin compared to those with minimal vegetable intake.

- Physical Activity and Bone Density: Post-menopausal women engaging in weight-bearing exercises will maintain better bone density than those who don’t.

- Intermittent Fasting and Metabolism: Individuals practicing intermittent fasting will demonstrate a more efficient metabolism rate than those on regular diets.

- Public Transport and Air Quality: Cities with extensive public transport systems will have better air quality than cities primarily reliant on individual car use.

- Sleep Duration and Immunity: Adults sleeping between 7-9 hours nightly will have stronger immune responses than those sleeping less or more than this range.

- Hands-on Learning and Skill Retention: Students taught through hands-on practical methods will retain technical skills better than those taught purely theoretically.

- Nature Exposure and Concentration: Regular breaks involving nature exposure during work will result in higher concentration levels than indoor breaks.

- Yoga and Stress Reduction: Individuals practicing daily yoga sessions will experience a more significant reduction in stress levels compared to non-practitioners.

- Pet Ownership and Loneliness: People who own pets, especially dogs or cats, will report lower feelings of loneliness than those without pets.

- Bilingualism and Cognitive Flexibility: Individuals who are bilingual will exhibit higher cognitive flexibility compared to those who speak only one language.

- Green Tea and Weight Loss: Regular consumption of green tea will result in a higher rate of weight loss than those who consume other beverages.

- Plant-based Diets and Heart Health: Individuals following a plant-based diet will show a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases compared to those on omnivorous diets.

- Forest Bathing and Mental Wellbeing: People who frequently engage in forest bathing or nature walks will demonstrate improved mental wellbeing than those who don’t.

- Online Learning and Independence: Students who predominantly learn through online platforms will develop stronger independent study habits than those in traditional classroom settings.

- Gardening and Life Satisfaction: Individuals engaged in regular gardening will report higher life satisfaction scores than non-gardeners.

- Video Games and Reflexes: People who play action video games frequently will exhibit quicker reflexes than non-gamers.

- Daily Meditation and Anxiety Levels: Individuals who practice daily meditation sessions will experience reduced anxiety levels compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Volunteering and Self-esteem: Regular volunteers will have higher self-esteem and a more positive outlook than those who don’t volunteer.

- Art Therapy and Emotional Expression: Individuals undergoing art therapy will exhibit a broader range of emotional expression than those undergoing traditional counseling.

- Morning Sunlight and Sleep Patterns: Exposure to morning sunlight will result in better nighttime sleep quality than exposure to late afternoon sunlight.

- Probiotics and Digestive Health: Regular intake of probiotics will lead to improved gut health and fewer digestive issues than those not consuming probiotics.

- Digital Detox and Social Skills: Individuals who frequently engage in digital detoxes will develop better face-to-face social skills than constant device users.

- Physical Libraries and Reading Habits: Students with access to physical libraries will exhibit more consistent reading habits than those relying solely on digital sources.

- Public Speaking Training and Confidence: Individuals who undergo public speaking training will express higher confidence levels in various social scenarios than those who don’t.

- Music Lessons and Mathematical Abilities: Children who take music lessons, especially in instruments like the piano, will show improved mathematical abilities compared to non-musical peers.

- Dance and Coordination: Engaging in dance classes will lead to better physical coordination and balance than other forms of exercise.

- Home Cooking and Nutritional Intake: Individuals who predominantly consume home-cooked meals will have a more balanced nutritional intake than those relying on take-out or restaurant meals.

- Organic Foods and Health Outcomes: Individuals consuming predominantly organic foods will exhibit fewer health issues related to preservatives and pesticides than those consuming conventionally grown foods.

- Podcast Consumption and Listening Skills: People who regularly listen to podcasts will demonstrate better active listening skills compared to those who rarely or never listen to podcasts.

- Urban Farming and Community Engagement: Urban areas with community farming initiatives will experience higher levels of community engagement and social interaction than areas without such initiatives.

- Mindfulness Practices and Emotional Regulation: Individuals practicing mindfulness techniques, like deep breathing or body scans, will manage their emotional responses better than those not practicing mindfulness.

- E-books and Reading Speed: People who primarily read e-books will exhibit a faster reading speed compared to those reading printed books.

- Aerobic Exercises and Endurance: Engaging in regular aerobic exercises will lead to higher endurance levels compared to anaerobic exercises.

- Digital Note-taking and Information Retention: Students who use digital platforms for note-taking will retain and recall information less effectively than those taking handwritten notes.

- Cycling to Work and Cardiovascular Health: Individuals who cycle to work will have better cardiovascular health than those who commute using motorized transportation.

- Active Learning Techniques and Academic Performance: Students exposed to active learning strategies will perform better academically than students in traditional lecture-based settings.

- Ergonomic Workspaces and Physical Discomfort: Workers who use ergonomic office furniture will report fewer musculoskeletal problems than those using conventional office furniture.

- Reforestation Initiatives and Air Quality: Areas with proactive reforestation initiatives will have significantly better air quality than areas without such efforts.

- Mediterranean Diet and Lifespan: People following a Mediterranean diet will generally have a longer lifespan compared to those following Western diets.

- Virtual Reality Training and Skill Acquisition: Individuals trained using virtual reality platforms will acquire new skills more rapidly than those trained using traditional methods.

- Solar Energy Adoption and Electricity Bills: Households that adopt solar energy solutions will experience lower monthly electricity bills than those relying solely on grid electricity.

- Journaling and Stress Reduction: Regular journaling will lead to a more significant reduction in perceived stress levels than non-journaling practices.

- Noise-cancelling Headphones and Productivity: Workers using noise-cancelling headphones in open office environments will show higher productivity levels than those not using such headphones.

- Early Birds and Task Efficiency: Individuals who start their day early, or “early birds”, will generally be more efficient in completing tasks than night owls.

- Coding Bootcamps and Job Placement: Graduates from coding bootcamps will find job placements more rapidly than those with only traditional computer science degrees.

- Plant-based Milks and Lactose Intolerance: Consuming plant-based milks, such as almond or oat milk, will cause fewer digestive problems for lactose-intolerant individuals than cow’s milk.

- Sensory Deprivation Tanks and Creativity: Regular sessions in sensory deprivation tanks will lead to heightened creativity levels compared to traditional relaxation methods.

Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples for Psychology

In the realm of psychology, directional psychology hypothesis are valuable as they specifically predict the nature and direction of a relationship or effect. These statements make pointed predictions about expected outcomes in psychological studies, paving the way for focused investigations.

- Emotion Regulation Techniques: Individuals trained in emotion regulation techniques will exhibit lower levels of anxiety than those untrained.

- Positive Reinforcement in Learning: Children exposed to positive reinforcement will exhibit faster learning rates than those exposed to negative reinforcement.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Depression: Patients undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy will show more significant improvements in depressive symptoms than those using other therapeutic methods.

- Social Media Use and Self-esteem: Adolescents with higher social media usage will report lower self-esteem than their less active counterparts.

- Mindfulness Meditation and Attention Span: Regular practitioners of mindfulness meditation will have longer attention spans than non-practitioners.

- Childhood Trauma and Adult Relationships: Individuals who experienced trauma in childhood will display more attachment issues in adult romantic relationships than those without such experiences.

- Group Therapy and Social Skills: Individuals attending group therapy will demonstrate improved social skills compared to those receiving individual therapy.

- Extrinsic Motivation and Task Performance: Students driven by extrinsic motivation will have lower task persistence than those driven by intrinsic motivation.

- Visual Imagery and Memory Retention: Participants using visual imagery techniques will recall lists of items more effectively than those using rote memorization.

- Parenting Styles and Adolescent Rebellion: Adolescents raised with authoritarian parenting styles will show higher levels of rebellion than those raised with permissive styles.

Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples for Research

In research, a directional research hypothesis narrows down the prediction to a specific direction of the effect. These hypotheses can serve various fields, guiding researchers toward certain anticipated outcomes, making the study’s goal clearer.

- Online Learning Platforms and Student Engagement: Students using interactive online learning platforms will have higher engagement levels than those using traditional online formats.

- Work from Home and Employee Productivity: Employees working from home will report higher job satisfaction but slightly reduced productivity compared to office-going employees.

- Green Spaces and Urban Well-being: Urban areas with more green spaces will have residents reporting higher well-being scores than areas dominated by concrete.

- Dietary Fiber Intake and Digestive Health: Individuals consuming diets rich in fiber will have fewer digestive issues than those on low-fiber diets.

- Public Transportation and Air Quality: Cities that invest more in public transportation will experience better air quality than cities reliant on individual car usage.

- Gamification and Learning Outcomes: Educational modules that incorporate gamification will yield better learning outcomes than traditional modules.

- Open Source Software and System Security: Systems using open-source software will encounter fewer security breaches than those using proprietary software.

- Organic Farming and Soil Health: Farmlands practicing organic farming methods will have richer soil quality than conventionally farmed lands.

- Renewable Energy Sources and Power Grid Stability: Power grids utilizing a higher percentage of renewable energy sources will experience fewer outages than those predominantly using fossil fuels.

- Artificial Sweeteners and Weight Gain: Regular consumers of artificial sweeteners will not necessarily exhibit lower weight gain compared to consumers of natural sugars.

Directional Hypothesis Statement Examples for Correlation Study

Correlation studies evaluate the relationship between two or more variables. Directional hypotheses in correlation studies anticipate a specific type of association – either positive, negative, or neutral.

- Physical Activity and Mental Health: There will be a positive correlation between regular physical activity levels and self-reported mental well-being.

- Sedentary Lifestyle and Cardiovascular Issues: An increased sedentary lifestyle duration will correlate positively with cardiovascular health issues.

- Reading Habits and Vocabulary Size: There will be a positive correlation between the frequency of reading and the breadth of an individual’s vocabulary.

- Fast Food Consumption and Health Risks: A higher frequency of fast food consumption will correlate with increased health risks, such as obesity or high blood pressure.

- Financial Literacy and Debt Management: Individuals with higher financial literacy will have a negative correlation with unmanaged debts.

- Sleep Duration and Cognitive Performance: There will be a positive correlation between the optimal sleep duration (7-9 hours) and cognitive performance in adults.

- Volunteering and Life Satisfaction: Individuals who volunteer regularly will show a positive correlation with overall life satisfaction scores.

- Alcohol Consumption and Reaction Time: A higher frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption will negatively correlate with reaction times in motor tasks.

- Class Attendance and Academic Grades: There will be a positive correlation between the number of classes attended and the final academic grades of students.

- Eco-friendly Practices and Brand Loyalty: Brands adopting more eco-friendly practices will experience a positive correlation with consumer loyalty and trust.

Directional Hypothesis vs Non-Directional Hypothesis

Directional Hypothesis: A directional hypothesis , as the name implies, provides a specific direction for the expected relationship or difference between variables. It predicts which group will have higher or lower scores or how two variables will relate specifically, such as predicting that one variable will increase as the other decreases.

Advantages of a Directional Hypothesis:

- Offers clarity in predictions.

- Simplifies data interpretation, since the expected outcome is clearly stated.

- Can be based on previous research or established theories, lending more weight to its predictions.

Example of Directional Hypothesis: “Students who receive mindfulness training will have lower stress levels than those who do not receive such training.”

Non-Directional Hypothesis (Two-tailed Hypothesis): A non-directional hypothesis , on the other hand, merely states that there will be a difference between the two groups or a relationship between two variables without specifying the nature of this difference or relationship.

Advantages of a Non-Directional Hypothesis:

- Useful when research is exploratory in nature.

- Provides a broader scope for exploring unexpected results.

- Less bias as it doesn’t anticipate a specific outcome.

Example of Non-Directional Hypothesis: “Students who receive mindfulness training will have different stress levels than those who do not receive such training.”

How do you write a Directional Hypothesis Statement? – Step by Step Guide

1. Identify Your Variables: Before drafting a hypothesis, understand the dependent and independent variables in your study.

2. Review Previous Research: Consider findings from past studies or established theories to make informed predictions.

3. Be Specific: Clearly state which group or condition you expect to have higher or lower scores or how the variables will relate.

4. Keep It Simple: Ensure that the hypothesis is concise and free of jargon.

5. Make It Testable: Your hypothesis should be framed in such a way that it can be empirically tested through experiments or observations.

6. Revise and Refine: After drafting your hypothesis, review it to ensure clarity and relevance. Get feedback if possible.

7. State Confidently: Use definitive language, such as “will” rather than “might.”

Example of Writing Directional Hypothesis: Based on a study that indicates mindfulness reduces stress, and intending to research its impact on students, you might draft: “Students undergoing mindfulness practices will report lower stress levels.”

Tips for Writing a Directional Hypothesis Statement

1. Base Your Predictions on Evidence: Whenever possible, root your hypotheses in existing literature or preliminary observations.

2. Avoid Ambiguity: Be clear about the specific groups or conditions you are comparing.

3. Stay Focused: A hypothesis should address one primary question or relationship. If you find your hypothesis complicated, consider breaking it into multiple hypotheses.

4. Use Simple Language: Complex wording can muddle the clarity of your hypothesis. Ensure it’s understandable, even to those outside your field.

5. Review and Refine: After drafting, set it aside, then revisit with fresh eyes. It can also be helpful to get peers or mentors to review your hypothesis.

6. Avoid Personal Bias: Ensure your hypothesis is based on empirical evidence or theories and not personal beliefs or biases.

Remember, a directional hypothesis is just a starting point. While it provides a roadmap for your research, it’s essential to remain open to whatever results your study yields, even if they contradict your initial predictions.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

- Secondary School

Directional hypothesis

A hypothesis that is built upon a certain directional relationship between two variables and constructed upon an already existing theory, is called a directional hypothesis.

New questions in Psychology

- Social Studies

- High School

What might cause a researcher to state a directional hypothesis rather than a non-directional hypothesis? what about the reverse?

Expert-verified answer.

- 15.3K answers

- 17.7M people helped

The fact that may cause a researcher to state a directional hypothesis rather than a non-directional hypothesis is that it all depends upon the purpose of the study.

Let's say a pharmaceutical business wants to assess the differences between a potential new medicine and one they already sold. Assume the new product was produced at a considerably lower cost. They would need to know if the new item was superior. Consequently, this could be a better example: Theoretically, a new product has a decreased incidence of a particular adverse effect. A directed hypothesis might use this as an illustration.

Imagine a researcher who was interested in learning whether men or women consumed more or fewer eggs, but who had no idea what the result may be. This would suggest that the amount of eggs consumed by men and women is equal. This serves as an illustration of a non-directional hypothesis.

To learn more about directional hypothesis here,

brainly.com/question/11032292

- 13.4K answers

- 4.7M people helped

Final answer:

A researcher opts for a directional hypothesis when there is existing evidence or theory indicating a specific outcome, whereas a non-directional hypothesis is used in the absence of such evidence, representing a broader inquiry into an observed effect.

Explanation:

A researcher might state a directional hypothesis rather than a non-directional hypothesis when there is existing theory or preliminary data suggesting a particular effect or outcome. For instance, if previous studies indicate that sunlight exposure increases plant growth, a researcher may specifically predict that plants in sunlight will grow taller compared to those in the shade.

In contrast, a non-directional hypothesis is used when there is no strong basis for predicting the specific direction of an effect. As such, a researcher may simply hypothesize that there will be a difference in growth between plants exposed to sunlight and those that are not, without specifying which group will grow taller.

Inductive reasoning might lead to a non-directional hypothesis, beginning from observations to broader generalizations, while deductive reasoning often results in a directional hypothesis, moving from a general theory to specific predictions about outcomes.