Violence in Movies and Its Effects Cause and Effect Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Violence in movies has been a topic of a heated debate for many decades. Some people claim that violence in movies negatively affects people (especially adolescents), whereas others argue that violence in movies does not lead to violence in life. However, there is one thing researchers agree upon: movies only reveal trends existing in the contemporary society. It is agreed that violence in movies appear as it is a part of the human society.

Thus, the cause of violence in movies is quite clear, but its effects are still unidentified. The ongoing research provides quite controversial data on the matter. However, it is necessary to note that violence in movies does affect many people (especially adolescents) as some start seeking for more violence in media or real-life, some become ‘inspired’ by the films or may feel depressed for a while.

In the first place, it is necessary to note that adolescents are the most vulnerable group. Reportedly, adolescents tend to seek for violent imagery more than adults do (Kirsh 90). A number of surveys show that “individuals who are high in sensation seeking find violence in television and film more appealing than do their low sensation-seeking counterparts” (Kirsh 90).

These adolescents prefer watching films with more violence. This need is yet to be explained. However, researchers agree that adolescents tend to be more aggressive than adults. In other words, researchers note that adolescence is the period of the human life that is associated with most aggression.

Notably, watching violence on TV can become insufficient for some adolescents who will start seeking for it in real life. Apart from watching violent scenes, some adolescents can become eager to participate in such scenes (and video games will not be enough). Some may even wish to initiate violent episodes to get new experiences.

At this point it is necessary to mention another possible effect of violence in movies. Researchers claim that violence in media can affect adolescents’ self-efficacy. In other words, young people can feel more confident when they associate themselves with certain characters created by filmmakers (Kirsh 102). Thus, watching superheroes or ‘tough guys’ coping with difficulties can positively affect adolescents’ self-efficacy. Apart from this, sometimes these adolescents can feel like exercising their power and initiate some violent episodes.

Watching films containing violence can provide young people with ideas how to exercise their power. Some films can be regarded as a guide full of tips. Adolescents can try to repeat actions and ‘amusements’ revealed in a film. More so, Simmons provides a detailed analysis of reception of two films which contained a lot of violent scenes and notes that those films (like many other movies) tell a story of young men who were involved in a number of violent episodes and remained unpunished.

The author notes that people believed that the major message of the film was as follows: “If there were enough hoodlums and they behaved in a menacing way, they could get away with it” (qtd. in Simmons 385). Therefore, adolescents may wish to try things they see in movies. Of course, only some adolescents can seek for violence in real life.

Some adolescents may detest violence and feel depressed when they watch it. Thus, violent scenes may haunt adolescents in their dreams, which can lead to certain anxiety or even depression. Unfortunately, now people are exposed to violence on TV.

Notably, Simmons notes that violence has become an indispensible part of movies since the middle of the twentieth century when people understood that violence in movies brought money (390). Vast majority of films contain violent scenes. Sometimes it is simply impossible to be sure the film is violence-free, even if its genre is defined as a romantic comedy.

Thus, the group of adolescents who are less sensation-seeking may feel anxious about violent scenes, but they will hardly escape from watching a violent scene even if they stop watching action movies. Besides, victimized adolescents can also feel uneasy watching violent scenes as they may associate themselves with the victims in the films. These scenes can bring back memories of events which adolescents try to forget. Admittedly, this can contribute to their anxiety and depressive symptoms, which are common for adolescents.

To sum up, even though many people argue that violence in films has no effect on people, it is clear that violent scenes do affect some groups, e.g. adolescents. Violence in movies can make adolescents more aggressive and make them seek for more violence. Violent scenes can also be regarded as certain kind of guide to follow in real life as some adolescents will feel like trying some ‘tricks’ shown.

Finally, violence in films can contribute to development of anxiety or depressive symptoms in adolescents. Of course, violence is a part of the human society and will inevitably be revealed in movies. However, filmmakers should be more thoughtful when incorporating violence into their films. They should try to seek for other tools to reveal their ideas and they should cut down the amount of violence in movies.

Works Cited

Kirsh, Steven J. Children, Adolescents, and Media Violence: A Critical Look at the Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2006. Print.

Simmons, J. “Violent Youth: The Censoring and Public Reception of “The Wild One” and “The Blackboard Jungle”.” Film History 20.3 (2008): 381-391. Print.

- Independent Study: Tim Burton

- The Film "Walk the Line" and the Role of Music in It

- Great Game of Life (GGOL) Program: Simmons

- "Why I Don't Do Crossfit" by Erin Simmons

- "Global Environment History" a Book by Ian G. Simmons

- Director’s Cinematic Vision in Films

- One Aspect of Cinema During the Silent Era

- How is One Particular Film Similar to, and Different From, Other Films Made by the same Director or Studio?

- A Beautiful Mind: Understanding Schizophrenia and Its Impact on the Individual and the Family

- Summary of "We Were Soldiers" Movie

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 6). Violence in Movies and Its Effects. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-in-movies-and-its-effects/

"Violence in Movies and Its Effects." IvyPanda , 6 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/violence-in-movies-and-its-effects/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Violence in Movies and Its Effects'. 6 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Violence in Movies and Its Effects." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-in-movies-and-its-effects/.

1. IvyPanda . "Violence in Movies and Its Effects." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-in-movies-and-its-effects/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Violence in Movies and Its Effects." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-in-movies-and-its-effects/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- About The Journalist’s Resource

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Violent media and real-world behavior: Historical data and recent trends

2015 study from Stetson University published in Journal of Communications that explores violence in movies and video games and rates of societal violence over the same period.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Devon Maylie, The Journalist's Resource February 18, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/violent-media-real-world-behavior-historical-data-recent-trends/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The relationship between violent media and real-world violence has been the subject of extensive debate and considerable academic research , yet the core question is far from answered. Do violent games and movies encourage more violence, less, or is there no effect? Complicating matters is what seems like a simultaneous rise in onscreen mayhem and the number of bloody events in our streets — according to a 2014 report from the FBI, between 2007 and 2013 there were an average of 16.4 active-shooter incidents in the U.S. every year, more than 150% higher than the annual rate between 2000 and 2006.

But as has long been observed, any correlation is not necessarily causation . While Adam Lanza and James Holmes — respectively, the perpetrators of the Newtown and Aurora mass shootings — both played violent video games , so do millions of law-abiding Americans. A 2014 study in Psychology of Popular Media Culture found no evidence of an association between violent crime and video game sales and the release dates of popular violent video games. “Unexpectedly, many of the results were suggestive of a decrease in violent crime in response to violent video games,” write the researchers, based at Villanova and Rutgers. A 2015 study from the University of Toledo showed that playing violent video games could desensitize children and youth to violence, but didn’t establish a definitive connection with real-world behavior, positive or negative.

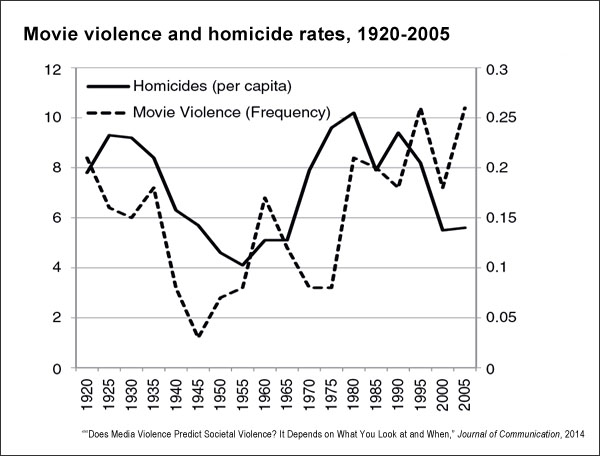

A 2014 study in Journal of Communication , “Does Media Violence Predict Societal Violence? It Depends on What You Look at and When,” builds on prior research to look closer at media portrayals of violence and rates of violent behavior. The research, by Christopher J. Ferguson of Stetson University, had two parts: The first measured the frequency and graphicness of violence in movies between 1920 and 2005 and compared it to homicide rates, median household income, policing, population density, youth population and GDP over the same period. The second part looked at the correlation between the consumption of violent video games and youth behavior from 1996 to 2011.

The study’s findings include:

- Overall, no evidence was found to support the conclusion that media violence and societal violence are meaningfully correlated.

- Across the 20th century the frequency of movie violence followed a rough U-pattern: It was common in the 1920s, then declined before rising again in the latter part of the 20th century. This appears to correspond to the period of the Motion Picture Production Code (known as the Hays Code), in force from 1930 to the late 1960s.

- The frequency of movie violence and murder rates were correlated in the mid-20th century, but not earlier or later in the period studied. “By the latter 20th century … movie violence [was] associated with reduced societal violence in the form of homicides. Further, the correlation between movie and societal violence was reduced when policing or real GDP were controlled.”

- The graphicness of movie violence shows an increasing pattern across the 20th century, particularly beginning in the 1950s, but did not correlate with societal violence.

- The second part of the study found that for the years 1996 to 2011, the consumption of violent video games was inversely related to youth violence.

- Youth violence decreased during the 15-year study period despite high levels of media violence in society. However, the study period is relatively short, the researcher cautioned, and therefore results could be imperfect.

“Results from the two studies suggest that socialization models of media violence may be inadequate to our understanding of the interaction between media and consumer behavior at least in regard to serious violence,” Ferguson concludes. “Adoption of a limited-effects model in which user motivations rather than content drive media experiences may help us understand how media can have influences, yet those influences result in only limited aggregate net impact in society.” Given that effects on individual users may differ widely, Ferguson suggests that policy discussion should be more focused on “more pressing” issues that influence violence in society such as poverty or mental health.

Related research: A 2015 research roundup, “The Contested Field of Violent Video Games,” gives an overview of recent scholarship on video games and societal violence, including ones that support a link and others that refute it. Also of interest is a 2014 research roundup, “Mass Murder, Shooting Sprees and Rampage Violence.”

Keywords: video games, violence, aggression, desensitization, empathy, technology, youth, cognition, guns, crime, entertainment

About The Author

Devon Maylie

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Violence, media effects, and criminology.

- Nickie D. Phillips Nickie D. Phillips Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, St. Francis College

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.189

- Published online: 27 July 2017

Debate surrounding the impact of media representations on violence and crime has raged for decades and shows no sign of abating. Over the years, the targets of concern have shifted from film to comic books to television to video games, but the central questions remain the same. What is the relationship between popular media and audience emotions, attitudes, and behaviors? While media effects research covers a vast range of topics—from the study of its persuasive effects in advertising to its positive impact on emotions and behaviors—of particular interest to criminologists is the relationship between violence in popular media and real-life aggression and violence. Does media violence cause aggression and/or violence?

The study of media effects is informed by a variety of theoretical perspectives and spans many disciplines including communications and media studies, psychology, medicine, sociology, and criminology. Decades of research have amassed on the topic, yet there is no clear agreement about the impact of media or about which methodologies are most appropriate. Instead, there continues to be disagreement about whether media portrayals of violence are a serious problem and, if so, how society should respond.

Conflicting interpretations of research findings inform and shape public debate around media effects. Although there seems to be a consensus among scholars that exposure to media violence impacts aggression, there is less agreement around its potential impact on violence and criminal behavior. While a few criminologists focus on the phenomenon of copycat crimes, most rarely engage with whether media directly causes violence. Instead, they explore broader considerations of the relationship between media, popular culture, and society.

- media exposure

- criminal behavior

- popular culture

- media violence

- media and crime

- copycat crimes

Media Exposure, Violence, and Aggression

On Friday July 22, 2016 , a gunman killed nine people at a mall in Munich, Germany. The 18-year-old shooter was subsequently characterized by the media as being under psychiatric care and harboring at least two obsessions. One, an obsession with mass shootings, including that of Anders Breivik who ultimately killed 77 people in Norway in 2011 , and the other an obsession with video games. A Los Angeles, California, news report stated that the gunman was “an avid player of first-person shooter video games, including ‘Counter-Strike,’” while another headline similarly declared, “Munich gunman, a fan of violent video games, rampage killers, had planned attack for a year”(CNN Wire, 2016 ; Reuters, 2016 ). This high-profile incident was hardly the first to link popular culture to violent crime. Notably, in the aftermath of the 1999 Columbine shooting massacre, for example, media sources implicated and later discredited music, video games, and a gothic aesthetic as causal factors of the crime (Cullen, 2009 ; Yamato, 2016 ). Other, more recent, incidents have echoed similar claims suggesting that popular culture has a nefarious influence on consumers.

Media violence and its impact on audiences are among the most researched and examined topics in communications studies (Hetsroni, 2007 ). Yet, debate over whether media violence causes aggression and violence persists, particularly in response to high-profile criminal incidents. Blaming video games, and other forms of media and popular culture, as contributing to violence is not a new phenomenon. However, interpreting media effects can be difficult because commenters often seem to indicate a grand consensus that understates more contradictory and nuanced interpretations of the data.

In fact, there is a consensus among many media researchers that media violence has an impact on aggression although its impact on violence is less clear. For example, in response to the shooting in Munich, Brad Bushman, professor of communication and psychology, avoided pinning the incident solely on video games, but in the process supported the assertion that video gameplay is linked to aggression. He stated,

While there isn’t complete consensus in any scientific field, a study we conducted showed more than 90% of pediatricians and about two-thirds of media researchers surveyed agreed that violent video games increase aggression in children. (Bushman, 2016 )

Others, too, have reached similar conclusions with regard to other media. In 2008 , psychologist John Murray summarized decades of research stating, “Fifty years of research on the effect of TV violence on children leads to the inescapable conclusion that viewing media violence is related to increases in aggressive attitudes, values, and behaviors” (Murray, 2008 , p. 1212). Scholars Glenn Sparks and Cheri Sparks similarly declared that,

Despite the fact that controversy still exists about the impact of media violence, the research results reveal a dominant and consistent pattern in favor of the notion that exposure to violent media images does increase the risk of aggressive behavior. (Sparks & Sparks, 2002 , p. 273)

In 2014 , psychologist Wayne Warburton more broadly concluded that the vast majority of studies have found “that exposure to violent media increases the likelihood of aggressive behavior in the short and longterm, increases hostile perceptions and attitudes, and desensitizes individuals to violent content” (Warburton, 2014 , p. 64).

Criminologists, too, are sensitive to the impact of media exposure. For example, Jacqueline Helfgott summarized the research:

There have been over 1000 studies on the effects of TV and film violence over the past 40 years. Research on the influence of TV violence on aggression has consistently shown that TV violence increases aggression and social anxiety, cultivates a “mean view” of the world, and negatively impacts real-world behavior. (Helfgott, 2015 , p. 50)

In his book, Media Coverage of Crime and Criminal Justice , criminologist Matthew Robinson stated, “Studies of the impact of media on violence are crystal clear in their findings and implications for society” (Robinson, 2011 , p. 135). He cited studies on childhood exposure to violent media leading to aggressive behavior as evidence. In his pioneering book Media, Crime, and Criminal Justice , criminologist Ray Surette concurred that media violence is linked to aggression, but offered a nuanced interpretation. He stated,

a small to modest but genuine causal role for media violence regarding viewer aggression has been established for most beyond a reasonable doubt . . . There is certainly a connection between violent media and social aggression, but its strength and configuration is simply not known at this time. (Surette, 2011 , p. 68)

The uncertainties about the strength of the relationship and the lack of evidence linking media violence to real-world violence is often lost in the news media accounts of high-profile violent crimes.

Media Exposure and Copycat Crimes

While many scholars do seem to agree that there is evidence that media violence—whether that of film, TV, or video games—increases aggression, they disagree about its impact on violent or criminal behavior (Ferguson, 2014 ; Gunter, 2008 ; Helfgott, 2015 ; Reiner, 2002 ; Savage, 2008 ). Nonetheless, it is violent incidents that most often prompt speculation that media causes violence. More specifically, violence that appears to mimic portrayals of violent media tends to ignite controversy. For example, the idea that films contribute to violent crime is not a new assertion. Films such as A Clockwork Orange , Menace II Society , Set it Off , and Child’s Play 3 , have been linked to crimes and at least eight murders have been linked to Oliver Stone’s 1994 film Natural Born Killers (Bracci, 2010 ; Brooks, 2002 ; PBS, n.d. ). Nonetheless, pinpointing a direct, causal relationship between media and violent crime remains elusive.

Criminologist Jacqueline Helfgott defined copycat crime as a “crime that is inspired by another crime” (Helfgott, 2015 , p. 51). The idea is that offenders model their behavior on media representations of violence whether real or fictional. One case, in particular, illustrated how popular culture, media, and criminal violence converge. On July 20, 2012 , James Holmes entered the midnight premiere of The Dark Knight Rises , the third film in the massively successful Batman trilogy, in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. He shot and killed 12 people and wounded 70 others. At the time, the New York Times described the incident,

Witnesses told the police that Mr. Holmes said something to the effect of “I am the Joker,” according to a federal law enforcement official, and that his hair had been dyed or he was wearing a wig. Then, as people began to rise from their seats in confusion or anxiety, he began to shoot. The gunman paused at least once, several witnesses said, perhaps to reload, and continued firing. (Frosch & Johnson, 2012 ).

The dyed hair, Holme’s alleged comment, and that the incident occurred at a popular screening led many to speculate that the shooter was influenced by the earlier film in the trilogy and reignited debate around the impact about media violence. The Daily Mail pointed out that Holmes may have been motivated by a 25-year-old Batman comic in which a gunman opens fire in a movie theater—thus further suggesting the iconic villain served as motivation for the attack (Graham & Gallagher, 2012 ). Perceptions of the “Joker connection” fed into the notion that popular media has a direct causal influence on violent behavior even as press reports later indicated that Holmes had not, in fact, made reference to the Joker (Meyer, 2015 ).

A week after the Aurora shooting, the New York Daily News published an article detailing a “possible copycat” crime. A suspect was arrested in his Maryland home after making threatening phone calls to his workplace. The article reported that the suspect stated, “I am a [sic] joker” and “I’m going to load my guns and blow everybody up.” In their search, police found “a lethal arsenal of 25 guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition” in the suspect’s home (McShane, 2012 ).

Though criminologists are generally skeptical that those who commit violent crimes are motivated solely by media violence, there does seem to be some evidence that media may be influential in shaping how some offenders commit crime. In his study of serious and violent juvenile offenders, criminologist Ray Surette found “about one out of three juveniles reports having considered a copycat crime and about one out of four reports actually having attempted one.” He concluded that “those juveniles who are self-reported copycats are significantly more likely to credit the media as both a general and personal influence.” Surette contended that though violent offenses garner the most media attention, copycat criminals are more likely to be career criminals and to commit property crimes rather than violent crimes (Surette, 2002 , pp. 56, 63; Surette 2011 ).

Discerning what crimes may be classified as copycat crimes is a challenge. Jacqueline Helfgott suggested they occur on a “continuum of influence.” On one end, she said, media plays a relatively minor role in being a “component of the modus operandi” of the offender, while on the other end, she said, “personality disordered media junkies” have difficulty distinguishing reality from violent fantasy. According to Helfgott, various factors such as individual characteristics, characteristics of media sources, relationship to media, demographic factors, and cultural factors are influential. Overall, scholars suggest that rather than pushing unsuspecting viewers to commit crimes, media more often influences how , rather than why, someone commits a crime (Helfgott, 2015 ; Marsh & Melville, 2014 ).

Given the public interest, there is relatively little research devoted to exactly what copycat crimes are and how they occur. Part of the problem of studying these types of crimes is the difficulty defining and measuring the concept. In an effort to clarify and empirically measure the phenomenon, Surette offered a scale that included seven indicators of copycat crimes. He used the following factors to identify copycat crimes: time order (media exposure must occur before the crime); time proximity (a five-year cut-off point of exposure); theme consistency (“a pattern of thought, feeling or behavior in the offender which closely parallels the media model”); scene specificity (mimicking a specific scene); repetitive viewing; self-editing (repeated viewing of single scene while “the balance of the film is ignored”); and offender statements and second-party statements indicating the influence of media. Findings demonstrated that cases are often prematurely, if not erroneously, labeled as “copycat.” Surette suggested that use of the scale offers a more precise way for researchers to objectively measure trends and frequency of copycat crimes (Surette, 2016 , p. 8).

Media Exposure and Violent Crimes

Overall, a causal link between media exposure and violent criminal behavior has yet to be validated, and most researchers steer clear of making such causal assumptions. Instead, many emphasize that media does not directly cause aggression and violence so much as operate as a risk factor among other variables (Bushman & Anderson, 2015 ; Warburton, 2014 ). In their review of media effects, Brad Bushman and psychologist Craig Anderson concluded,

In sum, extant research shows that media violence is a causal risk factor not only for mild forms of aggression but also for more serious forms of aggression, including violent criminal behavior. That does not mean that violent media exposure by itself will turn a normal child or adolescent who has few or no other risk factors into a violent criminal or a school shooter. Such extreme violence is rare, and tends to occur only when multiple risk factors converge in time, space, and within an individual. (Bushman & Anderson, 2015 , p. 1817)

Surette, however, argued that there is no clear linkage between media exposure and criminal behavior—violent or otherwise. In other words, a link between media violence and aggression does not necessarily mean that exposure to violent media causes violent (or nonviolent) criminal behavior. Though there are thousands of articles addressing media effects, many of these consist of reviews or commentary about prior research findings rather than original studies (Brown, 2007 ; Murray, 2008 ; Savage, 2008 ; Surette, 2011 ). Fewer, still, are studies that specifically measure media violence and criminal behavior (Gunter, 2008 ; Strasburger & Donnerstein, 2014 ). In their meta-analysis investigating the link between media violence and criminal aggression, scholars Joanne Savage and Christina Yancey did not find support for the assertion. Instead, they concluded,

The study of most consequence for violent crime policy actually found that exposure to media violence was significantly negatively related to violent crime rates at the aggregate level . . . It is plain to us that the relationship between exposure to violent media and serious violence has yet to be established. (Savage & Yancey, 2008 , p. 786)

Researchers continue to measure the impact of media violence among various forms of media and generally stop short of drawing a direct causal link in favor of more indirect effects. For example, one study examined the increase of gun violence in films over the years and concluded that violent scenes provide scripts for youth that justify gun violence that, in turn, may amplify aggression (Bushman, Jamieson, Weitz, & Romer, 2013 ). But others report contradictory findings. Patrick Markey and colleagues studied the relationship between rates of homicide and aggravated assault and gun violence in films from 1960–2012 and found that over the years, violent content in films increased while crime rates declined . After controlling for age shifts, poverty, education, incarceration rates, and economic inequality, the relationships remained statistically non-significant (Markey, French, & Markey, 2015 , p. 165). Psychologist Christopher Ferguson also failed to find a relationship between media violence in films and video games and violence (Ferguson, 2014 ).

Another study, by Gordon Dahl and Stefano DellaVigna, examined violent films from 1995–2004 and found decreases in violent crimes coincided with violent blockbuster movie attendance. Here, it was not the content that was alleged to impact crime rates, but instead what the authors called “voluntary incapacitation,” or the shifting of daily activities from that of potential criminal behavior to movie attendance. The authors concluded, “For each million people watching a strongly or mildly violent movie, respectively, violent crime decreases by 1.9% and 2.1%. Nonviolent movies have no statistically significant impact” (Dahl & DellaVigna, p. 39).

High-profile cases over the last several years have shifted public concern toward the perceived danger of video games, but research demonstrating a link between video games and criminal violence remains scant. The American Psychiatric Association declared that “research demonstrates a consistent relation between violent video game use and increases in aggressive behavior, aggressive cognitions and aggressive affect, and decreases in prosocial behavior, empathy and sensitivity to aggression . . .” but stopped short of claiming that video games impact criminal violence. According to Breuer and colleagues, “While all of the available meta-analyses . . . found a relationship between aggression and the use of (violent) video games, the size and interpretation of this connection differ largely between these studies . . .” (APA, 2015 ; Breuer et al., 2015 ; DeCamp, 2015 ). Further, psychologists Patrick Markey, Charlotte Markey, and Juliana French conducted four time-series analyses investigating the relationship between video game habits and assault and homicide rates. The studies measured rates of violent crime, the annual and monthly video game sales, Internet searches for video game walkthroughs, and rates of violent crime occurring after the release dates of popular games. The results showed that there was no relationship between video game habits and rates of aggravated assault and homicide. Instead, there was some indication of decreases in crime (Markey, Markey, & French, 2015 ).

Another longitudinal study failed to find video games as a predictor of aggression, instead finding support for the “selection hypothesis”—that physically aggressive individuals (aged 14–17) were more likely to choose media content that contained violence than those slightly older, aged 18–21. Additionally, the researchers concluded,

that violent media do not have a substantial impact on aggressive personality or behavior, at least in the phases of late adolescence and early adulthood that we focused on. (Breuer, Vogelgesang, Quandt, & Festl, 2015 , p. 324)

Overall, the lack of a consistent finding demonstrating that media exposure causes violent crime may not be particularly surprising given that studies linking media exposure, aggression, and violence suffer from a host of general criticisms. By way of explanation, social theorist David Gauntlett maintained that researchers frequently employ problematic definitions of aggression and violence, questionable methodologies, rely too much on fictional violence, neglect the social meaning of violence, and assume the third-person effect—that is, assume that other, vulnerable people are impacted by media, but “we” are not (Ferguson & Dyck, 2012 ; Gauntlett, 2001 ).

Others, such as scholars Martin Barker and Julian Petley, flatly reject the notion that violent media exposure is a causal factor for aggression and/or violence. In their book Ill Effects , the authors stated instead that it is simply “stupid” to query about “what are the effects of [media] violence” without taking context into account (p. 2). They counter what they describe as moral campaigners who advance the idea that media violence causes violence. Instead, Barker and Petley argue that audiences interpret media violence in a variety of ways based on their histories, experiences, and knowledge, and as such, it makes little sense to claim media “cause” violence (Barker & Petley, 2001 ).

Given the seemingly inconclusive and contradictory findings regarding media effects research, to say that the debate can, at times, be contentious is an understatement. One article published in European Psychologist queried “Does Doing Media Violence Research Make One Aggressive?” and lamented that the debate had devolved into an ideological one (Elson & Ferguson, 2013 ). Another academic journal published a special issue devoted to video games and youth and included a transcript of exchanges between two scholars to demonstrate that a “peaceful debate” was, in fact, possible (Ferguson & Konijn, 2015 ).

Nonetheless, in this debate, the stakes are high and the policy consequences profound. After examining over 900 published articles, publication patterns, prominent authors and coauthors, and disciplinary interest in the topic, scholar James Anderson argued that prominent media effects scholars, whom he deems the “causationists,” had developed a cottage industry dependent on funding by agencies focused primarily on the negative effects of media on children. Anderson argued that such a focus presents media as a threat to family values and ultimately operates as a zero-sum game. As a result, attention and resources are diverted toward media and away from other priorities that are essential to understanding aggression such as social disadvantage, substance abuse, and parental conflict (Anderson, 2008 , p. 1276).

Theoretical Perspectives on Media Effects

Understanding how media may impact attitudes and behavior has been the focus of media and communications studies for decades. Numerous theoretical perspectives offer insight into how and to what extent the media impacts the audience. As scholar Jenny Kitzinger documented in 2004 , there are generally two ways to approach the study of media effects. One is to foreground the power of media. That is, to suggest that the media holds powerful sway over viewers. Another perspective is to foreground the power and heterogeneity of the audience and to recognize that it is comprised of active agents (Kitzinger, 2004 ).

The notion of an all-powerful media can be traced to the influence of scholars affiliated with the Institute for Social Research, or Frankfurt School, in the 1930–1940s and proponents of the mass society theory. The institute was originally founded in Germany but later moved to the United States. Criminologist Yvonne Jewkes outlined how mass society theory assumed that members of the public were susceptible to media messages. This, theorists argued, was a result of rapidly changing social conditions and industrialization that produced isolated, impressionable individuals “cut adrift from kinship and organic ties and lacking moral cohesion” (Jewkes, 2015 , p. 13). In this historical context, in the era of World War II, the impact of Nazi propaganda was particularly resonant. Here, the media was believed to exhibit a unidirectional flow, operating as a powerful force influencing the masses. The most useful metaphor for this perspective described the media as a “hypodermic syringe” that could “‘inject’ values, ideas and information directly into the passive receiver producing direct and unmediated ‘effects’” (Jewkes, 2015 , pp. 16, 34). Though the hypodermic syringe model seems simplistic today, the idea that the media is all-powerful continues to inform contemporary public discourse around media and violence.

Concern of the power of media captured the attention of researchers interested in its purported negative impact on children. In one of the earliest series of studies in the United States during the late 1920s–1930s, researchers attempted to quantitatively measure media effects with the Payne Fund Studies. For example, they investigated how film, a relatively new medium, impacted children’s attitudes and behaviors, including antisocial and violent behavior. At the time, the Payne Fund Studies’ findings fueled the notion that children were indeed negatively influenced by films. This prompted the film industry to adopt a self-imposed code regulating content (Sparks & Sparks, 2002 ; Surette, 2011 ). Not everyone agreed with the approach. In fact, the methodologies employed in the studies received much criticism, and ultimately, the movement was branded as a moral crusade to regulate film content. Scholars Garth Jowett, Ian Jarvie, and Kathryn Fuller wrote about the significance of the studies,

We have seen this same policy battle fought and refought over radio, television, rock and roll, music videos and video games. Their researchers looked to see if intuitive concerns could be given concrete, measurable expression in research. While they had partial success, as have all subsequent efforts, they also ran into intractable problems . . . Since that day, no way has yet been found to resolve the dilemma of cause and effect: do crime movies create more crime, or do the criminally inclined enjoy and perhaps imitate crime movies? (Jowett, Jarvie, & Fuller, 1996 , p. 12)

As the debate continued, more sophisticated theoretical perspectives emerged. Efforts to empirically measure the impact of media on aggression and violence continued, albeit with equivocal results. In the 1950s and 1960s, psychological behaviorism, or understanding psychological motivations through observable behavior, became a prominent lens through which to view the causal impact of media violence. This type of research was exemplified by Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll studies demonstrating that children exposed to aggressive behavior, either observed in real life or on film, behaved more aggressively than those in control groups who were not exposed to the behavior. The assumption derived was that children learn through exposure and imitate behavior (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963 ). Though influential, the Bandura experiments were nevertheless heavily criticized. Some argued the laboratory conditions under which children were exposed to media were not generalizable to real-life conditions. Others challenged the assumption that children absorb media content in an unsophisticated manner without being able to distinguish between fantasy and reality. In fact, later studies did find children to be more discerning consumers of media than popularly believed (Gauntlett, 2001 ).

Hugely influential in our understandings of human behavior, the concept of social learning has been at the core of more contemporary understandings of media effects. For example, scholar Christopher Ferguson noted that the General Aggression Model (GAM), rooted in social learning and cognitive theory, has for decades been a dominant model for understanding how media impacts aggression and violence. GAM is described as the idea that “aggression is learned by the activation and repetition of cognitive scripts coupled with the desensitization of emotional responses due to repeated exposure.” However, Ferguson noted that its usefulness has been debated and advocated for a paradigm shift (Ferguson, 2013 , pp. 65, 27; Krahé, 2014 ).

Though the methodologies of the Payne Fund Studies and Bandura studies were heavily criticized, concern over media effects continued to be tied to larger moral debates including the fear of moral decline and concern over the welfare of children. Most notably, in the 1950s, psychiatrist Frederic Wertham warned of the dangers of comic books, a hugely popular medium at the time, and their impact on juveniles. Based on anecdotes and his clinical experience with children, Wertham argued that images of graphic violence and sexual debauchery in comic books were linked to juvenile delinquency. Though he was far from the only critic of comic book content, his criticisms reached the masses and gained further notoriety with the publication of his 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent . Wertham described the comic book content thusly,

The stories have a lot of crime and gunplay and, in addition, alluring advertisements of guns, some of them full-page and in bright colors, with four guns of various sizes and descriptions on a page . . . Here is the repetition of violence and sexiness which no Freud, Krafft-Ebing or Havelock Ellis ever dreamed could be offered to children, and in such profusion . . . I have come to the conclusion that this chronic stimulation, temptation and seduction by comic books, both their content and their alluring advertisements of knives and guns, are contributing factors to many children’s maladjustment. (Wertham, 1954 , p. 39)

Wertham’s work was instrumental in shaping public opinion and policies about the dangers of comic books. Concern about the impact of comics reached its apex in 1954 with the United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. Wertham testified before the committee, arguing that comics were a leading cause of juvenile delinquency. Ultimately, the protest of graphic content in comic books by various interest groups contributed to implementation of the publishers’ self-censorship code, the Comics Code Authority, which essentially designated select books that were deemed “safe” for children (Nyberg, 1998 ). The code remained in place for decades, though it was eventually relaxed and decades later phased out by the two most dominant publishers, DC and Marvel.

Wertham’s work, however influential in impacting the comic industry, was ultimately panned by academics. Although scholar Bart Beaty characterized Wertham’s position as more nuanced, if not progressive, than the mythology that followed him, Wertham was broadly dismissed as a moral reactionary (Beaty, 2005 ; Phillips & Strobl, 2013 ). The most damning criticism of Wertham’s work came decades later, from Carol Tilley’s examination of Wertham’s files. She concluded that in Seduction of the Innocent ,

Wertham manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence—especially that evidence he attributed to personal clinical research with young people—for rhetorical gain. (Tilley, 2012 , p. 386)

Tilley linked Wertham’s approach to that of the Frankfurt theorists who deemed popular culture a social threat and contended that Wertham was most interested in “cultural correction” rather than scientific inquiry (Tilley, 2012 , p. 404).

Over the decades, concern about the moral impact of media remained while theoretical and methodological approaches to media effects studies continued to evolve (Rich, Bickham, & Wartella, 2015 ). In what many consider a sophisticated development, theorists began to view the audience as more active and multifaceted than the mass society perspective allowed (Kitzinger, 2004 ). One perspective, based on a “uses and gratifications” model, assumes that rather than a passive audience being injected with values and information, a more active audience selects and “uses” media as a response to their needs and desires. Studies of uses and gratifications take into account how choice of media is influenced by one’s psychological and social circumstances. In this context, media provides a variety of functions for consumers who may engage with it for the purposes of gathering information, reducing boredom, seeking enjoyment, or facilitating communication (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1973 ; Rubin, 2002 ). This approach differs from earlier views in that it privileges the perspective and agency of the audience.

Another approach, the cultivation theory, gained momentum among researchers in the 1970s and has been of particular interest to criminologists. It focuses on how television television viewing impacts viewers’ attitudes toward social reality. The theory was first introduced by communications scholar George Gerbner, who argued the importance of understanding messages that long-term viewers absorb. Rather than examine the effect of specific content within any given programming, cultivation theory,

looks at exposure to massive flows of messages over long periods of time. The cultivation process takes place in the interaction of the viewer with the message; neither the message nor the viewer are all-powerful. (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, Singnorielli, & Shanahan, 2002 , p. 48)

In other words, he argued, television viewers are, over time, exposed to messages about the way the world works. As Gerbner and colleagues stated, “continued exposure to its messages is likely to reiterate, confirm, and nourish—that is, cultivate—its own values and perspectives” (p. 49).

One of the most well-known consequences of heavy media exposure is what Gerbner termed the “mean world” syndrome. He coined it based on studies that found that long-term exposure to media violence among heavy television viewers, “tends to cultivate the image of a relatively mean and dangerous world” (p. 52). Inherent in Gerbner’s view was that media representations are separate and distinct entities from “real life.” That is, it is the distorted representations of crime and violence that cultivate the notion that the world is a dangerous place. In this context, Gerbner found that heavy television viewers are more likely to be fearful of crime and to overestimate their chances of being a victim of violence (Gerbner, 1994 ).

Though there is evidence in support of cultivation theory, the strength of the relationship between media exposure and fear of crime is inconclusive. This is in part due to the recognition that audience members are not homogenous. Instead, researchers have found that there are many factors that impact the cultivating process. This includes, but is not limited to, “class, race, gender, place of residence, and actual experience of crime” (Reiner, 2002 ; Sparks, 1992 ). Or, as Ted Chiricos and colleagues remarked in their study of crime news and fear of crime, “The issue is not whether media accounts of crime increase fear, but which audiences, with which experiences and interests, construct which meanings from the messages received” (Chiricos, Eschholz, & Gertz, p. 354).

Other researchers found that exposure to media violence creates a desensitizing effect, that is, that as viewers consume more violent media, they become less empathetic as well as psychologically and emotionally numb when confronted with actual violence (Bartholow, Bushman, & Sestir, 2006 ; Carnagey, Anderson, & Bushman, 2007 ; Cline, Croft, & Courrier, 1973 ; Fanti, Vanman, Henrich, & Avraamides, 2009 ; Krahé et al., 2011 ). Other scholars such as Henry Giroux, however, point out that our contemporary culture is awash in violence and “everyone is infected.” From this perspective, the focus is not on certain individuals whose exposure to violent media leads to a desensitization of real-life violence, but rather on the notion that violence so permeates society that it has become normalized in ways that are divorced from ethical and moral implications. Giroux wrote,

While it would be wrong to suggest that the violence that saturates popular culture directly causes violence in the larger society, it is arguable that such violence serves not only to produce an insensitivity to real life violence but also functions to normalize violence as both a source of pleasure and as a practice for addressing social issues. When young people and others begin to believe that a world of extreme violence, vengeance, lawlessness, and revenge is the only world they inhabit, the culture and practice of real-life violence is more difficult to scrutinize, resist, and transform . . . (Giroux, 2015 )

For Giroux, the danger is that the normalization of violence has become a threat to democracy itself. In our culture of mass consumption shaped by neoliberal logics, depoliticized narratives of violence have become desired forms of entertainment and are presented in ways that express tolerance for some forms of violence while delegitimizing other forms of violence. In their book, Disposable Futures , Brad Evans and Henry Giroux argued that as the spectacle of violence perpetuates fear of inevitable catastrophe, it reinforces expansion of police powers, increased militarization and other forms of social control, and ultimately renders marginalized members of the populace disposable (Evans & Giroux, 2015 , p. 81).

Criminology and the “Media/Crime Nexus”

Most criminologists and sociologists who focus on media and crime are generally either dismissive of the notion that media violence directly causes violence or conclude that findings are more complex than traditional media effects models allow, preferring to focus attention on the impact of media violence on society rather than individual behavior (Carrabine, 2008 ; Ferrell, Hayward, & Young, 2015 ; Jewkes, 2015 ; Kitzinger, 2004 ; Marsh & Melville, 2014 ; Rafter, 2006 ; Sternheimer, 2003 ; Sternheimer 2013 ; Surette, 2011 ). Sociologist Karen Sternheimer forcefully declared “media culture is not the root cause of American social problems, not the Big Bad Wolf, as our ongoing public discussion would suggest” (Sternheimer, 2003 , p. 3). Sternheimer rejected the idea that media causes violence and argued that a false connection has been forged between media, popular culture, and violence. Like others critical of a singular focus on media, Sternheimer posited that overemphasis on the perceived dangers of media violence serves as a red herring that directs attention away from the actual causes of violence rooted in factors such as poverty, family violence, abuse, and economic inequalities (Sternheimer, 2003 , 2013 ). Similarly, in her Media and Crime text, Yvonne Jewkes stated that U.K. scholars tend to reject findings of a causal link because the studies are too reductionist; criminal behavior cannot be reduced to a single causal factor such as media consumption. Echoing Gauntlett’s critiques of media effects research, Jewkes stated that simplistic causal assumptions ignore “the wider context of a lifetime of meaning-making” (Jewkes, 2015 , p. 17).

Although they most often reject a “violent media cause violence” relationship, criminologists do not dismiss the notion of media as influential. To the contrary, over the decades much criminological interest has focused on the construction of social problems, the ideological implications of media, and media’s potential impact on crime policies and social control. Eamonn Carrabine noted that the focus of concern is not whether media directly causes violence but on “how the media promote damaging stereotypes of social groups, especially the young, to uphold the status quo” (Carrabine, 2008 , p. 34). Theoretically, these foci have been traced to the influence of cultural and Marxist studies. For example, criminologists frequently focus on how social anxieties and class inequalities impact our understandings of the relationship between media violence and attitudes, values, and behaviors. Influential works in the 1970s, such as Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order by Stuart Hall et al. and Stanley Cohen’s Folk Devils and Moral Panics , shifted criminological critique toward understanding media as a hegemonic force that reinforces state power and social control (Brown, 2011 ; Carrabine, 2008 ; Cohen, 2005 ; Garland, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2013 /1973, 2013/1973 ). Since that time, moral panic has become a common framework applied to public discourse around a variety of social issues including road rage, child abuse, popular music, sex panics, and drug abuse among others.

Into the 21st century , advances in technology, including increased use of social media, shifted the ways that criminologists approach the study of media effects. Scholar Sheila Brown traced how research in criminology evolved from a focus on “media and crime” to what she calls the “media/crime nexus” that recognizes that “media experience is real experience” (Brown, 2011 , p. 413). In other words, many criminologists began to reject as fallacy what social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson deemed “digital dualism,” or the notion that we have an “online” existence that is separate and distinct from our “off-line” existence. Instead, we exist simultaneously both online and offline, an

augmented reality that exists at the intersection of materiality and information, physicality and digitality, bodies and technology, atoms and bits, the off and the online. It is wrong to say “IRL” [in real life] to mean offline: Facebook is real life. (Jurgenson, 2012 )

The changing media landscape has been of particular interest to cultural criminologists. Michelle Brown recognized the omnipresence of media as significant in terms of methodological preferences and urged a move away from a focus on causality and predictability toward a more fluid approach that embraces the complex, contemporary media-saturated social reality characterized by uncertainty and instability (Brown, 2007 ).

Cultural criminologists have indeed rejected direct, causal relationships in favor of the recognition that social meanings of aggression and violence are constantly in transition, flowing through the media landscape, where “bits of information reverberate and bend back on themselves, creating a fluid porosity of meaning that defines late-modern life, and the nature of crime and media within it.” In other words, there is no linear relationship between crime and its representation. Instead, crime is viewed as inseparable from the culture in which our everyday lives are constantly re-created in loops and spirals that “amplify, distort, and define the experience of crime and criminality itself” (Ferrell, Hayward, & Young, 2015 , pp. 154–155). As an example of this shift in understanding media effects, criminologist Majid Yar proposed that we consider how the transition from being primarily consumers to primarily producers of content may serve as a motivating mechanism for criminal behavior. Here, Yar is suggesting that the proliferation of user-generated content via media technologies such as social media (i.e., the desire “to be seen” and to manage self-presentation) has a criminogenic component worthy of criminological inquiry (Yar, 2012 ). Shifting attention toward the media/crime nexus and away from traditional media effects analyses opens possibilities for a deeper understanding of the ways that media remains an integral part of our everyday lives and inseparable from our understandings of and engagement with crime and violence.

Over the years, from films to comic books to television to video games to social media, concerns over media effects have shifted along with changing technologies. While there seems to be some consensus that exposure to violent media impacts aggression, there is little evidence showing its impact on violent or criminal behavior. Nonetheless, high-profile violent crimes continue to reignite public interest in media effects, particularly with regard to copycat crimes.

At times, academic debate around media effects remains contentious and one’s academic discipline informs the study and interpretation of media effects. Criminologists and sociologists are generally reluctant to attribute violence and criminal behavior directly to exposure to violence media. They are, however, not dismissive of the impact of media on attitudes, social policies, and social control as evidenced by the myriad of studies on moral panics and other research that addresses the relationship between media, social anxieties, gender, race, and class inequalities. Scholars who study media effects are also sensitive to the historical context of the debates and ways that moral concerns shape public policies. The self-regulating codes of the film industry and the comic book industry have led scholars to be wary of hyperbole and policy overreach in response to claims of media effects. Future research will continue to explore ways that changing technologies, including increasing use of social media, will impact our understandings and perceptions of crime as well as criminal behavior.

Further Reading

- American Psychological Association . (2015). Resolution on violent video games . Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/policy/violent-video-games.aspx

- Anderson, J. A. , & Grimes, T. (2008). Special issue: Media violence. Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1059–1060.

- Berlatsky, N. (Ed.). (2012). Media violence: Opposing viewpoints . Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven.

- Elson, M. , & Ferguson, C. J. (2014). Twenty-five years of research on violence in digital games and aggression. European Psychologist , 19 (1), 33–46.

- Ferguson, C. (Ed.). (2015). Special issue: Video games and youth. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4).

- Ferguson, C. J. , Olson, C. K. , Kutner, L. A. , & Warner, D. E. (2014). Violent video games, catharsis seeking, bullying, and delinquency: A multivariate analysis of effects. Crime & Delinquency , 60 (5), 764–784.

- Gentile, D. (2013). Catharsis and media violence: A conceptual analysis. Societies , 3 (4), 491–510.

- Huesmann, L. R. (2007). The impact of electronic media violence: Scientific theory and research. Journal of Adolescent Health , 41 (6), S6–S13.

- Huesmann, L. R. , & Taylor, L. D. (2006). The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annual Review of Public Health , 27 (1), 393–415.

- Krahé, B. (Ed.). (2013). Special issue: Understanding media violence effects. Societies , 3 (3).

- Media Violence Commission, International Society for Research on Aggression (ISRA) . (2012). Report of the Media Violence Commission. Aggressive Behavior , 38 (5), 335–341.

- Rich, M. , & Bickham, D. (Eds.). (2015). Special issue: Methodological advances in the field of media influences on children. Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (14), 1731–1735.

- American Psychological Association (APA) . (2015, August 13). APA review confirms link between playing violent video games and aggression . Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2015/08/violent-video-games.aspx

- Anderson, J. A. (2008). The production of media violence and aggression research: A cultural analysis. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1260–1279.

- Bandura, A. , Ross, D. , & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 66 (1), 3–11.

- Barker, M. , & Petley, J. (2001). Ill effects: The media violence debate (2d ed.). London: Routledge.

- Bartholow, B. D. , Bushman, B. J. , & Sestir, M. A. (2006). Chronic violent video game exposure and desensitization to violence: Behavioral and event-related brain potential data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 42 (4), 532–539.

- Beaty, B. (2005). Fredric Wertham and the critique of mass culture . Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Bracci, P. (2010, March 12). The police were sure James Bulger’s ten-year-old killers were simply wicked. But should their parents have been in the dock? Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1257614/The-police-sure-James-Bulgers-year-old-killers-simply-wicked-But-parents-dock.html

- Breuer, J. , Vogelgesang, J. , Quandt, T. , & Festl, R. (2015). Violent video games and physical aggression: Evidence for a selection effect among adolescents. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 305–328.

- Brooks, X. (2002, December 19). Natural born copycats . Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2002/dec/20/artsfeatures1

- Brown, M. (2007). Beyond the requisites: Alternative starting points in the study of media effects and youth violence. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture , 14 (1), 1–20.

- Brown, S. (2011). Media/crime/millennium: Where are we now? A reflective review of research and theory directions in the 21st century. Sociology Compass , 5 (6), 413–425.

- Bushman, B. (2016, July 26). Violent video games and real violence: There’s a link but it’s not so simple . Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/violent-video-games-and-real-violence-theres-a-link-but-its-not-so-simple?63038

- Bushman, B. J. , & Anderson, C. A. (2015). Understanding causality in the effects of media violence. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (14), 1807–1821.

- Bushman, B. J. , Jamieson, P. E. , Weitz, I. , & Romer, D. (2013). Gun violence trends in movies. Pediatrics , 132 (6), 1014–1018.

- Carnagey, N. L. , Anderson, C. A. , & Bushman, B. J. (2007). The effect of video game violence on physiological desensitization to real-life violence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 43 (3), 489–496.

- Carrabine, E. (2008). Crime, culture and the media . Cambridge, U.K.: Polity.

- Chiricos, T. , Eschholz, S. , & Gertz, M. (1997). Crime, news and fear of crime: Toward an identification of audience effects. Social Problems , 44 , 342.

- Cline, V. B. , Croft, R. G. , & Courrier, S. (1973). Desensitization of children to television violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 27 (3), 360–365.

- CNN Wire (2016, July 24). Officials: 18-year-old suspect in Munich attack was obsessed with mass shootings . Retrieved from http://ktla.com/2016/07/24/18-year-old-suspect-in-munich-shooting-played-violent-video-games-had-mental-illness-officials/

- Cohen, S. (2005). Folk devils and moral panics (3d ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Cullen, D. (2009). Columbine . New York: Hachette.

- Dahl, G. , & DellaVigna, S. (2012). Does movie violence increase violent crime? In N. Berlatsky (Ed.), Media Violence: Opposing Viewpoints (pp. 36–43). Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven.

- DeCamp, W. (2015). Impersonal agencies of communication: Comparing the effects of video games and other risk factors on violence. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 296–304.

- Elson, M. , & Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Does doing media violence research make one aggressive? European Psychologist , 19 (1), 68–75.

- Evans, B. , & Giroux, H. (2015). Disposable futures: The seduction of violence in the age of spectacle . San Francisco: City Lights Publishers.

- Fanti, K. A. , Vanman, E. , Henrich, C. C. , & Avraamides, M. N. (2009). Desensitization to media violence over a short period of time. Aggressive Behavior , 35 (2), 179–187.

- Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Violent video games and the Supreme Court: Lessons for the scientific community in the wake of Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association. American Psychologist , 68 (2), 57–74.

- Ferguson, C. J. (2014). Does media violence predict societal violence? It depends on what you look at and when. Journal of Communication , 65 (1), E1–E22.

- Ferguson, C. J. , & Dyck, D. (2012). Paradigm change in aggression research: The time has come to retire the general aggression model. Aggression and Violent Behavior , 17 (3), 220–228.

- Ferguson, C. J. , & Konijn, E. A. (2015). She said/he said: A peaceful debate on video game violence. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 397–411.

- Ferrell, J. , Hayward, K. , & Young, J. (2015). Cultural criminology: An invitation . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Frosch, D. , & Johnson, K. (2012, July 20). 12 are killed at showing of Batman movie in Colorado . Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/21/us/shooting-at-colorado-theater-showing-batman-movie.html

- Garland, D. (2008). On the concept of moral panic. Crime, Media, Culture , 4 (1), 9–30.

- Gauntlett, D. (2001). The worrying influence of “media effects” studies. In ill effects: The media violence debate (2d ed.). London: Routledge.

- Gerbner, G. (1994). TV violence and the art of asking the wrong question. Retrieved from http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/tv-violence-and-art-asking-wrong-question

- Gerbner, G. , Gross, L. , Morgan, M. , Singnorielli, N. , & Shanahan, J. (2002). Growing up with television: Cultivation process. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 43–67). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Giroux, H. (2015, December 25). America’s addiction to violence . Retrieved from http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/12/25/americas-addiction-to-violence-2/

- Graham, C. , & Gallagher, I. (2012, July 20). Gunman who massacred 12 at movie premiere used same drugs that killed Batman star Heath Ledger . Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2176377/James-Holmes-Colorado-shooting-Gunman-used-drugs-killed-Heath-Ledger.html

- Gunter, B. (2008). Media violence: Is there a case for causality? American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1061–1122.

- Hall, S. , Critcher, C. , Jefferson, T. , Clarke, J. , & Roberts, B. (2013/1973). Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state and law and order . Hampshire, U.K.: Palgrave.

- Helfgott, J. B. (2015). Criminal behavior and the copycat effect: Literature review and theoretical framework for empirical investigation. Aggression and Violent Behavior , 22 (C), 46–64.

- Hetsroni, A. (2007). Four decades of violent content on prime-time network programming: A longitudinal meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication , 57 (4), 759–784.

- Jewkes, Y. (2015). Media & crime . London: SAGE.

- Jowett, G. , Jarvie, I. , & Fuller, K. (1996). Children and the movies: Media influence and the Payne Fund controversy . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Jurgenson, N. (2012, June 28). The IRL fetish . Retrieved from http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/the-irl-fetish/

- Katz, E. , Blumler, J. G. , & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly .

- Kitzinger, J. (2004). Framing abuse: Media influence and public understanding of sexual violence against children . London: Polity.

- Krahé, B. (2014). Restoring the spirit of fair play in the debate about violent video games. European Psychologist , 19 (1), 56–59.

- Krahé, B. , Möller, I. , Huesmann, L. R. , Kirwil, L. , Felber, J. , & Berger, A. (2011). Desensitization to media violence: Links with habitual media violence exposure, aggressive cognitions, and aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 100 (4), 630–646.

- Markey, P. M. , French, J. E. , & Markey, C. N. (2015). Violent movies and severe acts of violence: Sensationalism versus science. Human Communication Research , 41 (2), 155–173.

- Markey, P. M. , Markey, C. N. , & French, J. E. (2015). Violent video games and real-world violence: Rhetoric versus data. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 277–295.

- Marsh, I. , & Melville, G. (2014). Crime, justice and the media . New York: Routledge.

- McShane, L. (2012, July 27). Maryland police arrest possible Aurora copycat . Retrieved from http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/maryland-cops-thwart-aurora-theater-shooting-copycat-discover-gun-stash-included-20-weapons-400-rounds-ammo-article-1.1123265

- Meyer, J. (2015, September 18). The James Holmes “Joker” rumor . Retrieved from http://www.denverpost.com/2015/09/18/meyer-the-james-holmes-joker-rumor/

- Murray, J. P. (2008). Media violence: The effects are both real and strong. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1212–1230.

- Nyberg, A. K. (1998). Seal of approval: The history of the comics code. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- PBS . (n.d.). Culture shock: Flashpoints: Theater, film, and video: Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/cultureshock/flashpoints/theater/clockworkorange.html

- Phillips, N. D. , & Strobl, S. (2013). Comic book crime: Truth, justice, and the American way . New York: New York University Press.

- Rafter, N. (2006). Shots in the mirror: Crime films and society (2d ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reiner, R. (2002). Media made criminality: The representation of crime in the mass media. In R. Reiner , M. Maguire , & R. Morgan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of criminology (pp. 302–340). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reuters . (2016, July 24). Munich gunman, a fan of violent video games, rampage killers, had planned attack for a year . Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2016/07/24/munich-gunman-a-fan-of-violent-video-games-rampage-killers-had-planned-attack-for-a-year.html

- Rich, M. , Bickham, D. S. , & Wartella, E. (2015). Methodological advances in the field of media influences on children. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (14), 1731–1735.

- Robinson, M. B. (2011). Media coverage of crime and criminal justice. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Rubin, A. (2002). The uses-and-gratifications perspective of media effects. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 525–548). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Savage, J. (2008). The role of exposure to media violence in the etiology of violent behavior: A criminologist weighs in. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1123–1136.

- Savage, J. , & Yancey, C. (2008). The effects of media violence exposure on criminal aggression: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior , 35 (6), 772–791.

- Sparks, R. (1992). Television and the drama of crime: Moral tales and the place of crime in public life . Buckingham, U.K.: Open University Press.

- Sparks, G. , & Sparks, C. (2002). Effects of media violence. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (2d ed., pp. 269–286). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sternheimer, K. (2003). It’s not the media: The truth about pop culture’s influence on children . Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Sternheimer, K. (2013). Connecting social problems and popular culture: Why media is not the answer (2d ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Strasburger, V. C. , & Donnerstein, E. (2014). The new media of violent video games: Yet same old media problems? Clinical Pediatrics , 53 (8), 721–725.

- Surette, R. (2002). Self-reported copycat crime among a population of serious and violent juvenile offenders. Crime & Delinquency , 48 (1), 46–69.

- Surette, R. (2011). Media, crime, and criminal justice: Images, realities and policies (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Surette, R. (2016). Measuring copycat crime. Crime, Media, Culture , 12 (1), 37–64.

- Tilley, C. L. (2012). Seducing the innocent: Fredric Wertham and the falsifications that helped condemn comics. Information & Culture , 47 (4), 383–413.

- Warburton, W. (2014). Apples, oranges, and the burden of proof—putting media violence findings into context. European Psychologist , 19 (1), 60–67.

- Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of the innocent . New York: Rinehart.

- Yamato, J. (2016, June 14). Gaming industry mourns Orlando victims at E3—and sees no link between video games and gun violence . Retrieved from http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/06/14/gamers-mourn-orlando-victims-at-e3-and-see-no-link-between-gaming-and-gun-violence.html

- Yar, M. (2012). Crime, media and the will-to-representation: Reconsidering relationships in the new media age. Crime, Media, Culture , 8 (3), 245–260.

Related Articles

- Intimate Partner Violence

- The Extent and Nature of Gang Crime

- Intersecting Dimensions of Violence, Abuse, and Victimization

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Criminology and Criminal Justice. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 17 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Quentin Tarantino’s Ultimate Statement on Movie Violence

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood , the director’s ninth film, rates as his least bloody—and when mayhem erupts, it’s to draw a line between fiction and reality.

This article contains major spoilers for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood .

For his ninth and supposedly penultimate film, Quentin Tarantino gave up violence. In a way. To a point. The ever-polarizing writer-director is famed for his stylish and shocking scenes of brutality, which he’s used for cartoonish thrills ( Kill Bill ’s 89-person sword fight) , queasy comedy ( Pulp Fiction ’s accidental face-shooting ), and morally weighted horror ( Django Unchained ’s showcase of slaveholders’ cruelty ). But across most of its very charming and very languid run time, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood almost entirely forgoes gruesome outbursts in favor of chitchat, driving, and back-lot shenanigans. Two hours into the saga, some fan, sitting in some theater out there, is surely ready to accuse Tarantino of going soft this time.

Then comes the end of the movie, and the end of the movie’s relative peacefulness. Three Charles Manson followers—who, in reality, went on to kill five people, including the actress Sharon Tate—break in to the home of the washed-up actor Rick Dalton (played by Leonardo DiCaprio). These would-be slaughterers end up being slaughtered by Dalton and his stuntman, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), who employ an attack dog, a flamethrower, and a myriad of household objects that get slammed into faces. This flip of history triggered cackles of glee in my theater. It has also inspired wide speculation about Tarantino’s intent. What is the point of this ornate, ahistorical violence?

The answer might be that Tarantino is out to absolve Hollywood, and himself, from grotesqueries, excesses, insensitivities, and lapses. The undeniable magic of the movie, but also a nagging sense of strain and misdirection throughout, comes from its telling of a seductive lie: that the boundary between what happens in fiction and nonfiction is impermeable.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood ’s take on violence is evident not only in its splatter-caked climax but also through its few other, and milder, showdowns. Relatively early in the film, Booth gets challenged to an on-set duel by Bruce Lee (Mike Moh). By this point, viewers know a few things about Booth that make him seem dangerous: He’s a war veteran; he can leap great distances with ease; and he may have killed his wife, as revealed in a jarringly comic way moments earlier in the movie. Lee, of course, is the kung fu star who remains a legend today. When Booth laughs at Lee’s boasts about his supposedly lethal fists, Lee proposes a three-round brawl. (Lee’s family has objected to the portrayal of the star as “a mockery.”)