The Relevance of Systematic Reviews to Educational Policy and Practice

- September 2000

- Oxford Review of Education 26(3-4)

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

No full-text available

To read the full-text of this research, you can request a copy directly from the author.

- Riza Kadilar

- TEACH TEACH EDUC

- Leanne Cameron

- Rao Chandrasekhara

- Nannapaneni

- K V Krishna Kishore

- Nannapaneni Chandrasekhrarao

- Mohsen Hedayati

- Miltiadis Geropoulos

- J Intellect Disabil

- Nurhamidah Manullang

- Jailani Jailani

- Calista Devi Handaru

- Endang Sulistyowati

- Saba Hussain

- Jorge Knijnik

- Janine Chan

- Sholeh Hafidz

- Sami S Alshowiman

- Terri Pigott

- Caroline Sutton Chubb

- Hannah F. Scarbrough

- Prof Dev Educ

- MaryBeth Mercer

- Viktor Moskalets

- Oksana Fedyk

- Hatice DEMİR AYDOĞDU

- İlhan TURAN

- Dona Ningrum Mawardi

- Shenglan Zhang

- Victoria Elliott

- Steve Strand

- Andrea Norman

- Mario Torres

- Lolita Tabron

- Alexander Sturm

- CRIME JUSTICE

- Anthony Petrosino

- David B. Wilson

- D L Sackett

- William Rosenberg

- W. Scott Richardson

- J Clin Child Psychol

- Matthew J. Hoag

- CHILD ABUSE NEGLECT

- Donald T. Campbell

- Dina Okamoto

- Satish Iyengar

- D.T. Campbell

- J.C. Stanley

- Olatokumbo Fashola

- Adv Learn Behav Disabil

- Elliott M. Antman

- William Stock

- David P. Farrington

- BRIT EDUC RES J

- David H. Hargreaves

- Lee Joseph Cronbach

- Michael Agar

- James A. Kulik

- Chen-Lin C. Kulik

- Raymond W. Preiss

- Wax, Murray L., Ed

- Angela Lintz

- Kevin M. Gorey

- Debra E. Pawluck

- BJOG-INT J OBSTET GY

- Iain Chalmers

- MARC J. N. C

- Int J Educ Res

- Michael Louis

- Bruce Kupelnick

- Thomas C. Chalmers

- Br J Obstet Gynaecol

- Marc J. N. C. Keirse

- J CLIN EPIDEMIOL

- AM J MENT RETARD

- Robert Didden

- Julie A. Reeker

- David Ensing

- Jennifer G. Worrall

- A J Petrosino

- D H Hargreaves

- J E Schmidt

- D S Hartmann

- T A Mosteller

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- DOI: 10.1080/713688543

- Corpus ID: 145344372

The Relevance of Systematic Reviews to Educational Policy and Practice

- Published 1 September 2000

- Oxford Review of Education

238 Citations

Systematic reviews of research in science education: rigour or rigidity, reviewing research evidence in environmental education: some methodological reflections and challenges.

- Highly Influenced

Quality Indicators for Reviews of Research in Special Education

Systematic reviews: questions, methods and usage, a methodological review of systematic literature reviews in higher education: heterogeneity and homogeneity, beyond synthesis: augmenting systematic review procedures with practical principles to optimise impact and uptake in educational policy and practice, developing an evidence-based approach to management knowledge using systematic review, the use of research to improve professional practice: a systematic review of the literature, on 'systematic' reviews of research literatures: a 'narrative' response to evans & benefield, the value and purpose of the traditional qualitative literature review.

- 16 Excerpts

47 References

The concept of meta-analysis, best-evidence synthesis: an alternative to meta-analytic and traditional reviews.

- Highly Influential

Meta-Analysis for Explanation

The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment. confirmation from meta-analysis., meta-analysis in education: how has it been used, differential effectiveness of prevalent social work practice models: a meta-analysis, evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't, the effects of class size: an examination of rival hypotheses, meta-analysis of research on class size and achievement, a comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts. treatments for myocardial infarction., related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 19 February 2019

The dos and don’ts of influencing policy: a systematic review of advice to academics

- Kathryn Oliver ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4326-5258 1 &

- Paul Cairney 2

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 21 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

89k Accesses

172 Citations

873 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Politics and international relations

- Science, technology and society

A Correction to this article was published on 17 March 2020

This article has been updated

Many academics have strong incentives to influence policymaking, but may not know where to start. We searched systematically for, and synthesised, the ‘how to’ advice in the academic peer-reviewed and grey literatures. We condense this advice into eight main recommendations: (1) Do high quality research; (2) make your research relevant and readable; (3) understand policy processes; (4) be accessible to policymakers: engage routinely, flexible, and humbly; (5) decide if you want to be an issue advocate or honest broker; (6) build relationships (and ground rules) with policymakers; (7) be ‘entrepreneurial’ or find someone who is; and (8) reflect continuously: should you engage, do you want to, and is it working? This advice seems like common sense. However, it masks major inconsistencies, regarding different beliefs about the nature of the problem to be solved when using this advice. Furthermore, if not accompanied by critical analysis and insights from the peer-reviewed literature, it could provide misleading guidance for people new to this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them

Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice

Insights from a cross-sector review on how to conceptualise the quality of use of research evidence

Introduction.

Many academics have strong incentives to influence policymaking, as extrinsic motivation to show the ‘impact’ of their work to funding bodies, or intrinsic motivation to make a difference to policy. However, they may not know where to start (Evans and Cvitanovic, 2018 ). Although many academics have personal experience, or have attended impact training, there is a limited empirical evidence base to inform academics wishing to create impact. Although there is a significant amount of commentary about the processes and contexts affecting evidence use in policy and practice (Head, 2010 ; Whitty, 2015 ), the relative importance of different factors on achieving ‘impact’ has not been established (Haynes et al., 2011 ; Douglas, 2012 ; Wilkinson, 2017 ). Nor have common understandings of the concepts of ‘use’ or ‘impact’ themselves been developed. As pointed out by one of our reviewers, even empirical and conceptual papers often routinely fail to define or unpack these terms—with some exceptions (Weiss, 1979 ; Nutley et al., 2007 ; Parkhurst, 2017 ). Perhaps because of this theoretical paucity, there are few empirical evaluations of strategies to increase the uptake of evidence in policy and practice (Boaz et al., 2011 ), and those that exist tend not to offer advice for the individual academic. How then, should academics engage with policy?

There are substantial numbers of blogs, editorials, commentaries, which provide tips and suggestions for academics on how best to increase their impact, how to engage most effectively, or similar topics. We condense this advice into 8 main tips, to: produce high quality research, make it relevant, understand the policy processes in which you engage, be accessible to policymakers, decide if you want to offer policy advice, build networks, be ‘entrepreneurial’, and reflect on your activities.

Taken at face value, much of this advice is common sense, perhaps because it is inevitably bland and generic. When we interrogate it in more detail, we identify major inconsistencies in advice regarding: (a) what counts as good evidence, (b) how best to communicate it, (c) what policy engagement is for, (d) if engagement is to frame problems or simply measure them according to an existing frame, (e) how far to go to be useful and influential, (f) if you need and can produce ground rules or trust (g) what entrepreneurial means, and (h) how much choice researchers should have to engage in policymaking or not.

These inconsistencies reflect different beliefs about the nature of the problem to be solved when using this advice, which derive from unresolved debates about the nature and role of science and policy. We focus on three dilemmas that arise from engagement—for example, should you ‘co-produce’ research and policy and give policy recommendations?—and reflect on wider systemic issues, such as the causes of unequal rewards and punishments for engagement. Perhaps the biggest dilemma reflects the fact that engagement is a career choice, not an event: how far should you go to encourage the use of evidence in policy if you began your career as a researcher? These debates are rehearsed more fully and regularly in the peer-reviewed literature (Hammersley, 2013 ; de Leeuw et al., 2008 ; Fafard, 2015 ; Smith and Stewart, 2015 ; Smith and Stewart, 2017 ; Oliver and Faul, 2018 ), which have spawned narrative reviews of policy theory and systematic reviews of the literature on the ‘barriers and facilitators’ to the use of evidence in policy. For example, we know from policy studies that policymakers seek ways to act decisively, not produce more evidence until it speaks for itself; and, there is no simple way to link the supply of evidence to its demand in a policymaking system (see Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ). We draw on this literature to highlight inconsistencies and weaknesses in the advice offered to academics.

We assess how useful the ‘how to’ advice is for academics, to what extent the advice reflects the reality of policymaking and evidence use (based on our knowledge of the empirical and theoretical literatures, described more fully in Cairney and Oliver, 2018 ) and explore the implications of any mismatch between the two. We map and interrogate the ‘how to’ advice, by comparing it with the empirical and theoretical literature on creating impact, and on the policymaking context more broadly. We use these literatures to highlight key choices and tensions in engaging with policymakers, and signpost more useful, informed advice for academics on when, how, and if to engage with policymakers.

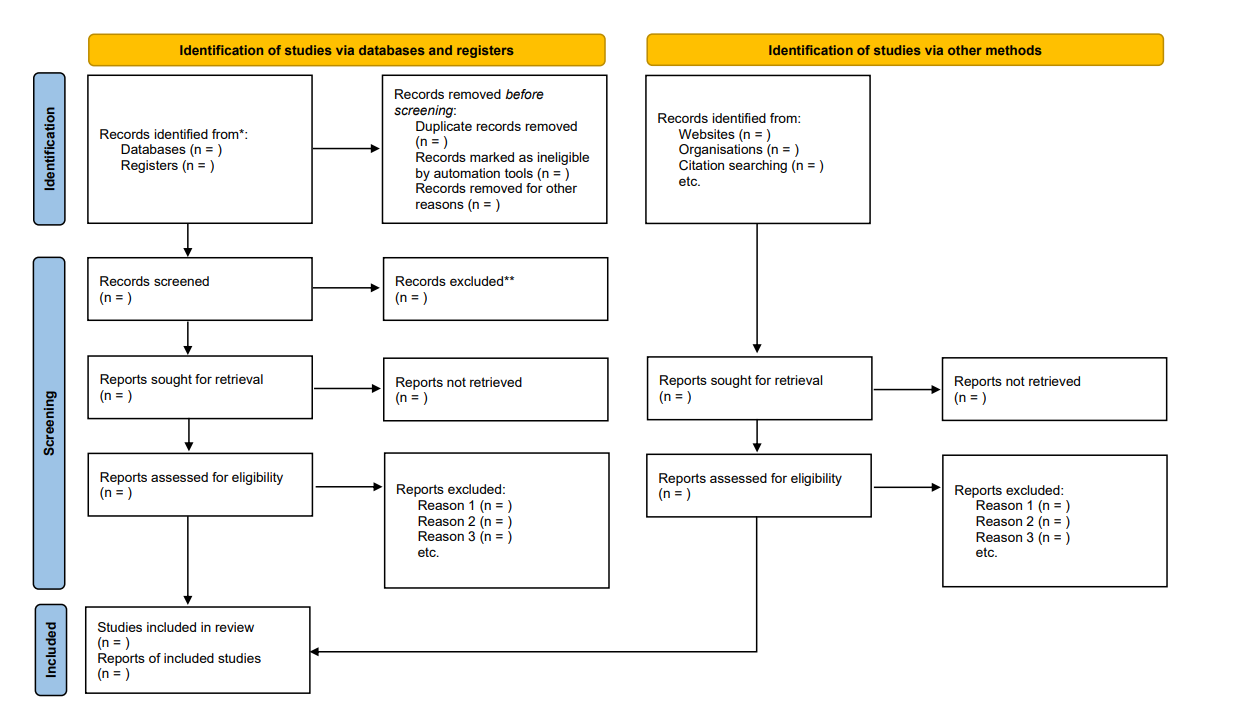

Methods: a systematic review of the ‘how to’ literature

Systematic review is a method to synthesise diverse evidence types on a clear defined problem (Petticrew and Roberts, 2008 ). Although most commonly associated with statistical methods to aggregate effect sizes (more accurately called meta-analyses), systematic reviews can be conducted on any body of written evidence, including grey or unpublished literature (Tyndall, 2008 ). All systematic reviews take steps to be transparent about the decisions made, the methods used to identify relevant evidence, and how this was synthesised to be transparent, replicable and exhaustive (resources allowing) (Gough et al., 2012 ). Primarily they involve clearly defined searches, inclusion and exclusion processes, and a quality assessment/synthesis process.

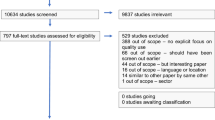

We searched three major electronic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar) and selected websites (e.g., ODI, Research Fortnight, Wonkhe) and journals (including Evidence and Policy, Policy and Politics, Research Policy), using a combination of terms. Terms such as evidence and impact were tested to search for articles explaining how to better ‘use’ evidence, or how to create policy ‘impact’. After testing, the search was conducted by combining the following terms, tailored to each database: ((evidence or science or scientist or researchers or impact), (help or advi* or tip* or "how to" or relevan*)) policy* OR practic* OR government* OR parliament*). We checked studies on full text where available and added them to a database for data-extraction. We conducted searches between June 30th and August 3rd 2018. We identified studies for data extraction when they covered these areas: Tips for researchers, tips for policymakers, types of useful research / characteristics of useful research, and other factors.

We included academic, policy and grey publications which offered advice to academics or policymakers on how to engage better with each other. We did not include: studies which explored the factors leading to evidence use, general commentaries on the roles of academics, or empirical analyses of the various initiatives, interventions, structures and roles of academics and researchers in policy (unless they offered primary data and tips on how to improve); book reviews; or, news reports. However, we use some of these publications to reflect more broadly on the historical changes to the academic-policy relationship.

We included 86 academic and non-academic publications in this review (see Table 1 for an overview). Although we found reports dating back to the 1950s on how governments and presidents (predominantly UK/US) do or do not use scientific advisors (Marshall, 1980 ; Bondi, 1982 ; Mayer, 1982 ; Lepkowski, 1984 ; Koshland Jr. et al., 1988 ; Sy, 1989 ; Krige, 1990 ; Srinivasan, 2000 ) and committees (Sapolsky, 1968 ; Wolfle, 1968 ; Editorial, 1972 ; Walsh, 1973 ; Nichols, 1988 ; Young and Jones, 1994 ; Lawler, 1997 ; Masood, 1999 ; Morgan et al., 2001 ; Oakley et al., 2003 ; Allen et al. 2012 ). The earliest publication included was from 1971 (Aurum, 1971 ). Thirty-four were published in the last two years, reflecting ever increasing interest in how academics can increase their impact on policy. Although some academic publications are included, we mainly found blogs, letters, and editorials, often in high-impact publications such as Cell, Science, Nature and the Lancet. Many were opinion pieces by people moving between policy officials and academic roles, or blogs by and for early career researchers on how to establish impactful careers.

The advice is very consistent over the last 80 years; and between disciplines as diverse as gerontology, ecology, and economics. As noted in an earlier systematic review, previous studies have identified hundreds of factors which act as barriers to the uptake of evidence in policy (Oliver et al., 2014 ), albeit unsupported by empirical evidence. Many of the advisory pieces address these barriers, assuming rather than demonstrating that their simple advice will help ease the flow of evidence into policy. The pieces also often cite each other, even to the extent of using the exact phrasing. Therefore, the combination of previous academic reviews with our survey of ‘how to’ advice reinforces our sense of ‘saturation’, in which we have identified all of the most relevant advice (available in written form). In our synthesis, using thematic analysis, we condense these tips into 8 main themes. Then, we analyse these tips critically, with reference to wider discussions in the peer-reviewed literature.

Eight key tips on ‘how to influence policy’

Do high quality research.

Researchers are advised to conduct high-quality, robust research (Boyd, 2013 ; Whitty, 2015 ; Docquier, 2017 ; Eisenstein, 2017 ) and provide it in a way that is timely, policy relevant, and easy to understand, but not at the expense of accuracy (Havens, 1992 ; Norse, 2005 ; Simera et al., 2010 ; Bilotta et al., 2015 ; Kerr et al., 2015 ; Olander et al. 2017 ; POST, 2017 ). Specific research methods, metrics and/or models should be used (Aguinis et al. 2010 ), with systematic reviews/evidence synthesis considered particularly useful for policymakers (Lavis et al., 2003 ; Sutherland, 2013 ; Caird et al., 2015 ; Andermann et al., 2016 ; Donnelly et al., 2018 ; Topp et al., 2018 ), and often also randomised controlled trials, properly piloted and evaluated (Walley et al., 2018 ). Truly interdisciplinary research is required to identify new perspectives (Chapman et al., 2015 ; Marshall and Cvitanovic, 2017 ) and explore the “practical significance” of research for policy and practice (Aguinis et al. 2010 ). Academics must communicate scientific uncertainty and the strengths and weaknesses of a piece of research (Norse, 2005 ; Aguinis et al., 2010 ; Tyler, 2013 ; Game et al., 2015 ; Sutherland and Burgman, 2015 ), and be trained to “estimate probabilities of events, quantities or model parameters” (Sutherland and Burgman, 2015 ). Be ‘policy-relevant’ (NCCPE, 2018 ; Maddox, 1996 ; Green et al., 2009 ; Farmer, 2010 ; Kerr et al., 2015 ; Colglazier, 2016 ; Tesar et al., 2016 ; Echt, 2017b ; Fleming and Pyenson, 2017 ; Olander et al., 2017 ; POST, 2017 ) (although this is rarely defined). Two exceptions include the advice for research programmes to be embedded within national and regional governmental programmes (Walley et al., 2018 ) and for researchers to provide policymakers with models estimating the harms and benefits of different policy options (Basbøll, 2018 ) (Topp et al., 2018 ).

Communicate well: make your research relevant and readable

Academics should engage in more effective dissemination, (NCCPE, 2018 ; Maddox, 1996 ; Green et al., 2009 ; Farmer, 2010 ; Kerr et al., 2015 ; Colglazier, 2016 ; Tesar et al., 2016 ; Echt, 2017b ; Fleming and Pyenson, 2017 ; Olander et al. 2017 ; POST, 2017 ), make data public, (Malakoff, 2017 ), and provide clear summaries and syntheses of problems and solutions (Maybin, 2016 ). Use a range of outputs (social media, blogs, policy briefs), to make sure that policy actors can contact you with follow up questions (POST, 2017 ) (Parry-Davies and Newell, 2014 ), and to write for generalist, but not ignorant readers (Hillman, 2016 ). Avoid jargon but don’t over-simplify (Farmer, 2010 ; Goodwin, 2013 ); make simple and definitive statements (Brumley, 2014 ), and communicate complexity (Fischoff, 2015 ; Marshall and Cvitanovic, 2017 ) (Whitty, 2015 ).

Some blogs advise academics to use established storytelling techniques to persuade policymakers of a course of action or better communicate scientific ideas. Produce good stories based on emotional appeals or humour to expand and engage your audience (Evans, 2013 ; Fischoff, 2015 ; Docquier, 2017 ; Petes and Meyer, 2018 ). Jones and Crow develop a point-by-point guide to creating a narrative through scene-setting, casting characters, establishing a plot, and equating the moral with a ‘solution to the policy problem’ (Jones and Crow, 2017 ; Jones and Crow, 2018 ).

Understand policy processes, policymaking context, and key actors

Academics are advised to get to know how policy works, and in particular to accept that the normative technocratic ideal of ‘evidence-based’ policymaking does not reflect the political nature of decision-making (Tyler, 2013 ; Echt, 2017a ). Policy decisions are ultimately taken by politicians on behalf of constituents, and technological proposals are only ever going to be part of a solution (Eisenstein, 2017 ). Some feel that science should hold a privileged position in policy (Gluckman, 2014 ; Reed and Evely, 2016 ) but many recognise that research is unlikely to translate directly into an off-the-shelf ready-to-wear policy proposal (Tyler, 2013 ; Gluckman, 2014 ; Prehn, 2018 ), and that policy rarely changes overnight (Marshall and Cvitanovic, 2017 ). Being pragmatic and managing one’s expectations about the likely impact of research on policy—which bears little resemblance to the ‘policy cycle’—is advised (Sutherland and Burgman, 2015 ; Tyler, 2013 ).

Second, learn the basics, such as the difference between the role of government and parliament, and between other types of policymakers (Tyler, 2013 ). Note that your policy audience is likely to change on a yearly basis if not more frequently (Hillman, 2016 ); that they have busy and constrained lives (Lloyd, 2016 ; Docquier, 2017 ; Prehn, 2018 ) and their own career concerns and pathways (Lloyd, 2016 ; Docquier, 2017 ; Prehn, 2018 ). Do not guess what might work; take the time to listen and learn from policy colleagues (Datta, 2018 ).

Third, learn to recognise broader policymaking dynamics, paying particular attention to changing policy priorities (Fischoff, 2015 ; Cairney, 2017 ). Academics are good at placing their work in the context of the academic literature, but also need to situate it in the “political landscape” (Himmrich, 2016 ). To do so means taking the time to learn what, when, where and who to influence (NCCPE, 2018 ; Marshall and Cvitanovic, 2017 ; Tilley et al., 2017 ) and getting to know audiences (Jones and Crow, 2018 ); learning about, and maximising use of established ways to engage, such as in advisory committees and expert panels (Gluckman, 2014 ; Pain, 2014 ; Malakoff, 2017 ; Hayes and Wilson, 2018 ) (Pain, 2014 ). Persistance and patience is advised—sticking at it, and changing strategy if it is not working (Graffy, 1999 ; Tilley et al., 2017 ).

Be ‘accessible’ to policymakers: engage routinely, flexibly, and humbly

Prehn uses the phrase ‘professional friends’, which encapsulates vague but popular concepts such as ‘build trust’ and ‘develop good relationships’ (Farmer, 2010 ; Kerr et al., 2015 ; Prehn, 2018 ). Building and maintaining long-term relationships takes effort, time and commitment (Goodwin, 2013 ; Maybin, 2016 ), can be easily damaged. It can take time to become established as a “trusted voice” (Goodwin, 2013 ) and may require a commitment to remaining non-partisan (Morgan et al. 2001 ). Therefore, build routine engagement on authentic relationships, developing a genuine rapport by listening and responding (Goodwin, 2013 ; Jo Clift Consulting, 2016 ; Petes and Meyer, 2018 ). Some suggest developing leadership and communication skills, but with reference to listening and learning (Petes and Meyer, 2018 ; Topp et al., 2018 ); Adopting a respectful, helpful, and humble demeanour, recognising that while academics are authorities on the evidence, we may not be the appropriate people to describe or design policy options (Nichols, 1972 ; Knottnerus and Tugwell, 2017 ) (although many disagree (Morgan et al., 2001 ; Morandi, 2009 )). Behave courteously by acting professionally (asking for feedback; responding promptly; following up meetings and conversations swiftly) (NCCPE, 2018 ; Goodwin, 2013 ; Jo Clift Consulting, 2016 ). Several commentators also reference the idea of ‘two cultures’ of policy and research (Shergold, 2011 ), which have their own language, practices and values (Goodwin, 2013 ). Learning to speak this language would enable researchers to better understand all that is said and unsaid in interactions (Jo Clift Consulting, 2016 ).

Decide if you want to be an ‘issue advocate’ or ‘honest broker’

Reflecting on accessibility should prompt researchers to consider how to draw the line between providing information or recommendations. One possibility is for researchers to simply disseminate their research honestly, clearly, and in a timely fashion, acting as an ‘honest broker’ of the evidence base (Pielke, 2007 ). In this mode, other actors may pick up and use evidence to influence policy in a number of ways—shaping the debate, framing issues, problematizing the construction of solutions and issues, explaining the options (Nichols, 1972 ; Knottnerus and Tugwell, 2017 )—while researchers seek to remain ‘neutral’. Another option is to recommend specific policy options or describe the implications for policy based on their research (Morgan et al., 2001 ; Morandi, 2009 ), perhaps by storytelling to indicate a preferred course of action (Evans, 2013 ; Fischoff, 2015 ; Docquier, 2017 ; Petes and Meyer, 2018 ). However, the boundary between these two options is very difficult to negotiate or identify in practice, particularly since policymakers often value candid judgements and opinions from people they trust, rather than new research (Maybin, 2016 ).

Build relationships (and ground rules) with policymakers

Getting to know policymakers better and building longer term networks (Chapman et al., 2015 ; Evans and Cvitanovic, 2018 ) could give researchers better access to opportunities to shape policy agendas (Colglazier, 2016 ; Lucey et al., 2017 ; Tilley et al., 2017 ), give themselves more credibility within the policy arena (Prehn, 2018 ), help researchers to identify the correct policy actors or champions to work with (Echt, 2017a ), and provide better insight into policy problems (Chapman et al., 2015 ; Colglazier, 2016 ; Lucey et al., 2017 ; Tilley et al., 2017 ). Working with policymakers as early as possible in the process helps develop shared interpretations of the policy problem (Echt, 2017b ; Tyler, 2017 ) and agreement on the purpose of research (Shergold, 2011 ). Co-designing, or otherwise doing research-for-policy together is widely held to be morally, ethically, and practically one of the best ways to achieve the elusive goal of getting evidence into policy (Sebba, 2011 ; Green, 2016 ; Eisenstein, 2017 ). Engaging publics more generally is also promoted (Chapman et al., 2015 ). Relationship-building activities require major investment and skills, and often go unrecognised (Prehn, 2018 ), but may offer the most likely route to get evidence into policy (Sebba, 2011 ; Green, 2016 ; Eisenstein, 2017 ). Initially, researchers can use blogs and social media (Brumley, 2014 ; POST, 2017 ) to increase their visibility to the policy community, combined with networking and direct approaches to policy actors (Tyler, 2013 ).

One of the few pieces built on a case study of impact argued that academics should build coalitions of allies, but also engage political opponents, and learn how to fight for their ideas (Coffait, 2017 ). However, collaboration can also lead to conflict and reputational damage (De Kerckhove et al., 2015 ). Therefore, when possible, academics should produce ground rules acceptable to academics and policymakers. They should be honest and thoughtful about how, when, and why to engage; and recognise the labour and resources required for successful engagement (Boaz et al., 2018 ). Successful engagement may require all parties to agree about processes , including ethics, consent, and confidentiality, and outputs , including data, intellectual property (De Kerckhove et al., 2015 ; Game et al., 2015 ; Hutchings and Stenseth, 2016 ). The organic development of these networks and contacts takes time and effort, and should be recognised as assets, particularly when offered new contacts by colleagues (Evans and Cvitanovic, 2018 ; Boaz et al., 2018 )

Be ‘entrepreneurial’ or find someone who is

Much of the ‘how to’ advice projects an image of a daring, persuasive scientist, comfortable in policy environments and always available when needed (Datta, 2018 ), by using mentors to build networks, or through ‘cold calling’ (Evans and Cvitanovic, 2018 ). Some ideas and values need to be fought for if they are to achieve dominance (Coffait, 2017 ; Docquier, 2017 ), and multiple strategies may be required, from leveraging trust in academics to advocating more generally for evidence based policy (Garrett, 2018 ). Academics are advised to develop “media-savvy” skills (Sebba, 2011 ), learn how to “sell the sizzle”(Farmer, 2010 ), become able to “convince people who think differently that shared action is possible,” (Fischoff, 2015 ), but also be pragmatic, by identifying real, tangible impacts and delivering them (Reed and Evely, 2016 ). Such a range of requirements may imply that being constantly available, and becoming part of the scenery, makes it more likely for a researcher to be the person to hand in an hour of need (Goodwin, 2013 ). Or, it could prompt a researcher to recognise their relative inability to be persuasive, and to hire a ‘knowledge broker’ to act on their behalf (Marshall and Cvitanovic, 2017 ; Quarmby, 2018 ).

Reflect continuously: should you engage, do you want to, and is it working?

Academics may be a good fit in the policy arena if they ‘want to be in real world’, ‘enjoy finding solutions to complex problems’ (Echt, 2017a ; Petes and Meyer, 2018 ), or are driven ‘by a passion greater than simply adding another item to your CV’ (Burgess, 2005 ). They should be genuinely motivated to take part in policy engagement, seeing it as a valuable exercise in its own right, as opposed to something instrumental to merely improve the stated impact of research (Goodwin, 2013 ). For example, scientists can “engage more productively in boundary work, which is defined as the ways in which scientists construct, negotiate, and defend the boundary between science and policy” (Rose, 2015 ). They can converse with policymakers about how science and scientific careers are affected by science policy, as a means of promoting more useful support within government (Pain, 2014 ). Or, they can use teaching to get students involved at an early stage in their careers, to train a new generation of impact-ready entrepreneurs (Hayes and Wilson, 2018 ). Such a profound requirement of one’s time should prompt constant reflection and refinement of practice. It is hard to know what our impact may be or how to sustain it (Reed and Evely, 2016 ). Therefore, academics who wish to engage must learn and reflect on the consequences of their actions (Datta, 2018 ; Topp et al., 2018 ).

The wider literature on the wider policymaking context

Our observation of this advice is that it is rather vague, very broad, and each theme contains a diversity of opinions. We also argue that much of this advice is based on misunderstandings about policy processes, and the roles of researchers and policymakers. We summarise these misunderstandings below (see Table 2 for an overview), by drawing a wider range of sources such as policy studies literature (Cairney, 2016 ) and a systematic review of factors influencing evidence use in policy (Oliver et al., 2014 ), to identify the wider context in which to understand and use these tips. We also contextualise these discussions in the broader evidence and policy/practice literature.

Firstly, there is no consensus over what counts as good evidence for policy (Oliver and de Vocht, 2015 ), and therefore how best to communicate good evidence . While we can probably agree what constitutes high quality research within each field, the criteria we use to assess it in many disciplines (such as generalisability and methodological rigour) have far lower salience for policymakers (Hammersley, 2013 ; Locock and Boaz, 2004 ). They do not adhere to the scientific idea of a ‘knowledge deficit’ in which our main collective aim is to reduce policymaker uncertainty by producing more of the best scientific evidence (Crow and Jones, 2018 ). Rather, evidence garners credibility, legitimacy and usefulness through its connections to individuals, networks and topical issues (Cash et al., 2003 ; Boaz et al., 2015 ; Oliver and Faul, 2018 ).

One way in which to understand the practical outcome of this distinction is to consider the profound consequences arising from the ways in which policymakers address their ‘bounded rationality’ (Simon, 1976 ; Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ). Individuals seek cognitive shortcuts to avoid decision-making ‘paralysis’—when faced with an overwhelming amount of possibly-relevant information—and allow them to process information efficiently enough to make choices (Gigerenzer and Selten, 2001 ). They combine ‘rational’ shortcuts, including trust in expertise and scientific sources, and ‘irrational’ shortcuts, to use their beliefs, emotions, habits, and familiarity with issues to identify policy problems and solutions (see Haidt, 2001 ; Kahneman, 2011 ; Lewis, 2013 ; Baumgartner, 2017 ; Jones and Thomas, 2017 ; Sloman and Fernbach, 2017 ). Therefore, we need to understand how they use such shortcuts to interpret their world, pay attention to issues, define issues as policy problems, and become more or less receptive to proposed solutions. In this scenario, effective policy actors—including advocates of research evidence—frame evidence to address the many ways to interpret policy problems (Cairney, 2016 ; Wellstead et al. 2018 ) and compete to draw attention to one ‘image’ of a problem and one feasible solution at the expense of the competition (Kingdon and Thurber, 1984 ; Majone, 1989 ; Baumgartner and Jones, 1993 ; Zahariadis, 2007 ). This debate determines the demand for evidence.

Secondly, there is little empirical guidance on how to gain the wide range of skills that researchers and policymakers need, to act collectively to address policymaking complexity, including to: produce evidence syntheses, manage expert communities, ‘co-produce’ research and policy with a wide range of stakeholders, and be prepared to offer policy recommendations as well as scientific advice (Topp et al., 2018 ). The list of skills includes the need to understand the policy processes in which you engage, such as by understanding the constituent parts of policymaking environments (John, 2003 , p. 488; (Cairney and Heikkila, 2014 ), p. 364–366) and their implications for the use of evidence:

Many actors make and influence policy in many ‘venues’ across many levels and types of government. Therefore, it is difficult to know where the ‘action’ is.

Each venue has its own ‘institutions’, or rules and norms maintained by many policymaking organisations. These rules can be formal and well understood, or informal, unwritten, and difficult to grasp (Ostrom, 2007a , 2007b ). Therefore, it takes time to learn the rules before being able to use them effectively.

These ‘rules of the game’ extend to policy networks, or the relationships between policymakers and influencers, many of which develop in ‘subsystems’ and contain relatively small groups of specialists. One can be a privileged insider in one venue but excluded from another, and the outcome may relate minimally to evidence.

Networks often reproduce dominant ‘ideas’ regarding the nature of the policy problem, the language we use to describe it, and the political feasibility of potential solutions (Kingdon and Thurber, 1984 ). Therefore, framing can make the difference between being listened to or ignored.

Policy conditions and events can reinforce or destabilise institutions. Evidence presented during crises or ‘focusing events’ (Birkland, 1997 ) can prompt lurches of attention from one issue to another, but this outcome is rare, and policy can remain unchanged for decades.

A one-size fits-all model is unlikely to help researchers navigate this environment where different audiences and institutions have different cultures, preferences and networks. Gaining knowledge of the complex policy context can be extremely challenging, yet the implications are profoundly important. In that context, theory-informed studies recommend investing your time over the long term, to build up alliances, trust in the messenger, knowledge of the system, and exploit ‘windows of opportunity’ for policy change (Cairney, 2016 , p.124). However, they also suggest that this investment of time may pay off only after years or decades—or not at all (Cairney and Oliver, 2018 ).

This context could have a profound impact on the way in which we interpret the eight tips. For example, it may:

tip the balance from scientific to policy-relevant measures of evidence quality;

shift the ways in which we communicate evidence from a focus on clarity to an emphasis on framing;

suggest that we need to engage with policymakers to such an extent that the division between honest broker and issue advocate become blurry;

prompt us to focus less on the ‘entrepreneurial’ skills of individual researchers and more on the nature of their environment; and

inform reflection on our role, since successful engagement may feel more like a career choice than an event.

Throughout this process, we need to decide what policy engagement is for —whether it is to frame problems or simply measure them according to an existing frame—and how far researchers should go to be useful and influential . While immersing oneself fully in policy processes may be the best way to achieve credibility and impact for researchers, there are significant consequences of becoming a political actor (Jasanoff and Polsby, 1991 ; Pielke, 2007 ; Haynes et al., 2011 ; Douglas, 2015 ). The most common consequences include criticism within one’s peer-group (Hutchings and Stenseth, 2016 ), being seen as an academic ‘lightweight’ (Maynard, 2015 ), and being used to add legitimacy to a policy position (Himmrich, 2016 ; Reed and Evely, 2016 ; Crouzat et al., 2018 ). More serious consequences include a loss of status completely—David Nutt famously lost his advisory role after publicly criticising UK government drug policy—and the loss of one’s safety if adopting an activist mindset (Zevallos, 2017 ). If academics need to go ‘all in’ to secure meaningful impact, we need to reflect on the extent to which they have the resources and support to do so.

Three major dilemmas in policy engagement

These misunderstandings matter, because well-meaning people are giving recommendations that are not based on empirical evidence, and may lead to significant risks, such as reputational damage and wasted resources. Further, their audience may reinforce this problem by holding onto deficit models of science and policy, and equating policy impact with a simple linear policy cycle. When unsuccessful, despite taking the ‘how to’ advice to heart, researchers may blame politics and policymakers rather than reflecting on their own role in a process they do not understand fully.

Although it is possible to synthesise the ‘how to’ advice into eight main themes, many categories contain a wide range of beliefs or recommendations within a very broad description of qualities like’ accessibility’ and ‘engagement’. We interrogate key examples to identify the wide range of (potentially contradictory) advice about the actual and desirable role of researchers in politics: whether to engage, how to engage, and the purpose of engagement.

Should academics try to influence policy?

A key area of disagreement was over the normative question of whether academics should advocate for policy positions, try to persuade policymakers of particular courses of action (e.g., Tilley et al., 2017 ), offer policy implications from their research (Goodwin, 2013 ), or be careful not to promote particular methods and policy approaches (Gluckman, 2014 ; Hutchings and Stenseth, 2016 ; Prehn, 2018 ). Aspects of the debate include:

The public duty to engage versus the need to protect science . Several pieces argued that publicly-paid academics should regard policy impact as a professional duty (Shergold, 2011 ; Tyler, 2017 ). If so, they should try: to influence policy by framing evidence into dominant policy narratives or to address issues that policymakers care about (Rose, 2015 ; Hillman, 2016 ; King, 2016 ), and engage in politics directly or when needed (Farmer, 2010 ; Petes and Meyer, 2018 ). Others felt that it risked an academic’s main asset – their independence of advice (Whitty, 2015 ; Alberts et al., 2018 ; Dodsworth and Cheeseman, 2018 )—and that this political role should be left to the specialists, such as scientific advisors (Hutchings and Stenseth, 2016 ). Others emphasise the potential costs to self-censorship (De Kerckhove et al., 2015 ), and the tension between being elite versus inclusive and accessible (Collins, 2011 ).

The potential for conflict and reputational damage . Some identify the tension between being able to provide rational advice to shape political discourse and the potential for conflict (De Kerckhove et al., 2015 ). Others rejected it as a false dichotomy, arguing that advocacy is a “continuous process of establishing relationships and creating a community of experts both in and outside of government who can give informed input on policies” (Himmrich, 2016 ).

The need to represent academics and academia : Some recommend discussing topics beyond your narrow expertise—almost as a representative for your field or profession (Petes and Meyer, 2018 )—while others caution against it, since speaking about one’s own expertise is the best way to maintain credibility (Marshall and Cvitanovic, 2017 ).

Such debates imply a choice to engage and do not routinely consider the unequal effects built on imbalances of power (Cairney and Oliver, 2018 ). Many researchers are required to show impact and it is not strictly a choice to engage. Further, there are significant career costs to engagement, which are relatively difficult to incur by more junior or untenured researchers, while women and people of colour may be more subject to personal abuse or exploitation. The risk of burnout, or the opportunity cost of doing impact rather than conducting the main activities of teaching and research jobs is too high for many (Graffy, 1999 ; Fischoff, 2015 ). Being constantly available, engaging with no clear guarantee of impact or success, with no payment for time or even travel is not possible for many researchers, even if that is the most likely way to achieve impact. This means that the diversity of voices available to policy is limited (Oliver and Faul, 2018 ). Much of the ‘how to’ advice is tailored to individuals without taking into account these systemic issues. They are mostly drawn from the experiences of people who consider themselves successful at influencing policy. The advice is likely to be useful mostly to a relatively similar group of people who are confident, comfortable in policy environments, and have both access and credibility within policy spaces. Thus, the current advice and structures may help reproduce and reinforce existing power dynamics and an underrepresentation of women, BAME, and people who otherwise do not fit the very narrow mould (Cairney and Oliver, 2018 )—even extending to the exclusion of academics from certain institutions or circles (Smith and Stewart, 2017 ).

How should academics influence policy?

A second dilemma is: how should academics try to influence policy? By merely stating the facts well, telling stories to influence our audience more, or working with our audience to help produce policy directly? Three main approaches were identified in the reviews. Firstly, to use specific tools such as evidence syntheses, or social media, to improve engagement (Thomson, 2013 ; Caird et al., 2015 ). This approach fits with the ‘deficit’ model of the evidence-policy relationships, whereby researchers merely provide content for others to work with. As extensively discussed elsewhere, this method, while safe, has not been shown to be effective at achieving policy change; and underpinning much of the advice in this strain are some serious misunderstandings about the practicalities, psychology and real world nature of policy change and information flow (Sturgis and Allum, 2004 ; Fernández, 2016 ; Simis et al., 2016 ).

Secondly, to use emotional appeals and storytelling to craft attractive narratives with the explicit aim of shaping policy options (Jones and Crow, 2017 ; Crow and Jones, 2018 ). Leaving aside the normative question of the independence of scientific research, or researchers’ responsibilities to represent data fully and honestly (Pielke, 2007 ), this strategy makes practical demands on the researcher. It requires having the personal charisma to engage diverse audiences and seem persuasive yet even-handed. Some of the advice suggests that academics try to seem pragmatic and equable about the outcome of any such approach, although not always clear whether this was to help the researcher seem more worldly-wise and sensible, or simply as a self-protective mechanism (King, 2016 ). Either way, deciding how to seem omnipotent yet credible; humble but authoritative; straightforward yet not over-simplifying—all while still appearing authentic—is probably beyond the scope of most of our acting abilities.

Thirdly, to collaborate (Oliver et al., 2014 ). Co-production is widely hailed as the most likely way to promote the use of research evidence in policy, as it would enable researchers to respond to policy agendas, and enable more agile multidisciplinary teams to coalesce around topical policy problems. There are also trade-offs to this way of working (Flinders et al., 2016 ). Researchers have to cede control over the research agenda and interpretations. This can give rise to accusations of bias, partisanship, or at least partiality for one political view over another. There are significant reputational risks involved in collaboration, within the academic community and outside it. Pragmatically, there are practical and logistical concerns about how and when to maintain control of intellectual property and access to data. More broadly, it may cloud one’s judgement about the research in hand, hindering one’s ability to think or speak critically without damaging working relationships.

What is the purpose of academics engagement in policymaking?

Authors do not always tell us the purpose of engagement before they tell us how to do it. Some warn against ‘tokenistic’ engagement, and there is plenty of advice for academics wanting to build ‘genuine’ rapport with policymakers to make their research more useful. Yet, it is not always clear if researchers should try and seem authentically interested in policymakers as a means of achieving impact or actually to listen, learn, and cede some control over the research process. The former can be damaging to the profession. As Goodwin points out, it’s not just policymakers who may feel short-changed by transactional relationships: “by treating policy engagement as an inconvenient and time-consuming ‘bolt on' you may close doors that could be left open for academics who genuinely care about this collaborative process” (Goodwin, 2013 ). The latter option is more radical. It involves a fundamentally different way of doing public engagement: one with no clear aim in mind other than to listen and learn, with the potential to transform research practices and outputs (Parry-Davies and Newell, 2014 ).

Although the literature helps us frame such dilemmas, it does not choose for us how to solve them. There are no clear answers on how scientists should act in relation to policymaking or the public (Mazanderani and Latour, 2018 ), but we can at least identify and clarify the dilemmas we face, and seek ways to navigate them. Therefore, it is imperative to move quickly from basic ‘how to’ advice towards a deeper understanding of the profound choices that shape careers and lives.

Conclusions

Academics are routinely urged to create impact from their research; to change policy, practice, and even population outcomes. There are, however, few empirical evaluations of strategies to enable academics to create impact. This lack of empirical evidence has not prevented people from offering advice based on their personal experience, rather than concrete evaluations of strategies to increase impact. Much of the advice demonstrates a limited understanding or description of policy processes and the wider social aspects of ‘doing’ science and research. The interactions between knowledge production and use may be so complex that abstract ‘how to’ advice is limited in use. The ‘how to’ advice has a potentially immense range, from very practical issues (how long should an executive summary be?) to very profound (should I risk my safety to secure policy change?), but few authors situate themselves in that wider context in which they provide advice.

There are some more thoughtful approaches which recognise more complex aspects of the task of influencing policy: the emotional, practical and cognitive labour of engaging; that it often goes unrewarded by employers; that impact is never certain, so engagement may remain unrewarded; and, that our current advice, structures and incentives have important implications for how we think about the roles and responsibilities of scientists when engaging with publics. Some of the ‘how to’ literature also considers the wider context of research production and use, noting that the risks and responsibilities are borne by individuals and, for example, one individual cannot possibly to get to know the whole policy machinery or predict the consequences of their engagement on policy or themselves. For example, universities, funders and academics are advised to develop incentives, structures to make ‘impact’ happen more easily (Kerr et al., 2015 ; Colglazier, 2016 ); and remove any actual or perceived penalisation of ‘doing’ public engagement (Maynard, 2015 ). Some suggest universities should move into the knowledge brokerage space, acting more like think-tanks (Shergold, 2011 ) by creating and championing policy-relevant evidence (Tyler, 2017 ), and providing “embedded gateways” which offer access to credible and high-quality research (Green, 2016 ). Similarly, governments have their own science advisory system which, they are advised, should be both independent, and inclusive and accountable (Morgan et al., 2001 ; Malakoff, 2017 ). Government and Parliament need to be mindful about the diversity of the experts and voices on which they draw. For example, historians and ethicists could help policymakers question their assumptions and explore historical patterns of policies and policy narratives in particular areas (Evans, 2013 ; Haddon et al., 2015 ) but economics and law have more currency with policymakers (Tyler, 2013 ).

However, we were often struck by the limited range of advice offered to academics, many of whom are at the beginning of their careers. This gap may leave each generation of scientists to fight the same battles, and learn the same lessons over again. In the absence of evidence about the effectiveness of these approaches, all one can do is suggest a cautious, learning approach to coproduction and engagement, while recognising that there is unlikely to be a one-size-fits all model which would lead to simple, actionable advice. Further, we do not detect a coherent vision for wider academy-policymaker relations. Since the impact agenda (in the UK, at least) is unlikely to recede any time soon, our best response as a profession is to interrogate it, shape and frame it, and to help us all to find ways to navigate the complex practical, political, moral and ethical challenges associated with being researchers today. The ‘how to’ literature can help, but only if authors are cognisant of their wider role in society and complex policymaking systems.

For some commentators, engagement is a safe choice tacked onto academic work. Yet, for many others, it is a more profound choice to engage for policy change while accepting that the punishments (such as personal threats or abuse) versus rewards (such as impact and career development opportunities) are shared highly unevenly across socioeconomic groups. Policy engagement is a career choice in which we seek opportunities for impact that may never arise, not an event in which an intense period of engagement produces results proportionate to effort.

Overall, we argue that the existing advice offered to academics on how to create impact is not based on empirical evidence, or on good understandings of key literatures on policymaking or evidence use. This leads to significant misunderstandings, and advice which can have potentially costly repercussions for research, researchers and policy. These limitations matter, as they lead to advice which fails to address core dilemmas for academics—whether to engage, how to engage, and why—which have profound implications for how scientists and universities should respond to the call for increased impact. Most of these tips focus on the individuals, whereas engagement between research and policy is driven by systemic factors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

17 march 2020.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Aguinis H, Werner S, Lanza Abbott J, Angert C, Joon Hyung P, Kohlhausen D (2010) Customer-centric science: reporting significant research results with rigor, relevance, and practical impact in mind. Organ Res Methods 13(3):515–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109333339

Article Google Scholar

Alberts B, Gold BD, Lee Martin L, Maxon ME, Martin LL, Maxon ME (2018) How to bring science and technology expertise to state governments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(9):19521955. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800543115

Article CAS Google Scholar

Allen DD, Lauffenburger J, Law AV, Pete Vanderveen R, Lang WG (2012) Report of the 2011-2012 standing committee on advocacy: the relevance of excellent research: strategies for impacting public policy. Am J Pharmaceut Educ 76(6). https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe766S6

Andermann A, Pang T, Newton JN, Davis A, Panisset U (2016) Evidence for health II: overcoming barriers to using evidence in policy and practice. Health Res Policy Syst 14(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0086-3 . BioMed Central

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Aurum (1971) Letter from London: science policy and the question of relevancy. Bull At Sci Routledge 27(6):25–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1971.11455376

Basbøll T (2018) We need our scientists to build models that frame our policies, not to tell stories that shape them, LSE Impact Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2018/07/30/we-need-our-scientists-to-build-models-that-frame-our-policies-not-to-tell-stories-that-shape-them/ . Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Baumgartner FR (2017) Endogenous disjoint change. Cogn Syst Res 44:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.04.001

Baumgartner FR, Jones BD (1993) Agendas and instability in American politics. University of Chicago Press: Chicago

Bilotta GS, Milner AM, Boyd IL (2015) How to increase the potential policy impact of environmental science research. Environ Sci Eur 27(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-015-0041-x

Birkland TA (1997) After disaster: agenda, public policy, and focusing events. American governance and public policy. Georgetown University Press, 178. http://press.georgetown.edu/book/georgetown/after-disaster . Accessed 17 July 2018

Boaz A, Baeza J, Fraser A (2011) Effective implementation of research into practice: an overview of systematic reviews of the health literature. BMC Res Notes https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-212 .

Boaz A, Hanney S, Borst R, O’Shea A, Kok M (2018) How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res Policy Syst 16(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6 . BioMed Central

Boaz A, Locock L, Ward V (2015) Whose evidence is it anyway? Evidence and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426515X14313738355534

Bondi H (1982) Science adviser to government. Interdiscip Sci Rev 7(1):9–13. https://doi.org/10.1179/030801882789801269

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Boyd I (2013) Research: a standard for policy-relevant science. Nature 501(7466):159–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/501159a

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brumley C (2014) Academia and storytelling are compatible–how to reduce the risks and gain control of your research narrative. LSE Impact Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2014/08/27/academic-storytelling-risk-reduction/ . Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Burgess J (2005) Follow the argument where it leads: Some personal reflections on “policy-relevant” research. Trans Inst Br Geogr 30(3):273–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474720500209X

Caird J, Sutcliffe K, Kwan I, Dickson K, Thomas J (2015) Mediating policy-relevant evidence at speed: are systematic reviews of systematic reviews a useful approach? Evid Policy 11(1):81–97. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13988609036850

Cairney P (2016) The politics of evidence-based policy making, The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making. 1–137. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51781-4

Google Scholar

Cairney P, Heikkila T (2014) A comparison of theories of the policy process. Theor Policy Process. p. 301–324

Cairney P, Kwiatkowski R (2017) How to communicate effectively with policymakers: Combine insights from psychology and policy studies. Palgrave Communications 3(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0046-8

Cairney P, Oliver K (2018) How should academics engage in policymaking to achieve impact? Polit Stud Rev https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807714

Cairney P (2017) Three habits of successful policy entrepreneurs|Paul Cairney: Politics and Public Policy, https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/2017/06/05/three-habits-of-successful-policy-entrepreneurs/ . Accessed 9 July 2018

Cash DW, Clark WC, Alcock F, Dickson NM, Eckley N, Guston DH, Jäger J, Mitchell RB (2003) Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100(14):8086–8091. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1231332100

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Chapman JM, Algera D, Dick M, Hawkins EE, Lawrence MJ, Lennox RJ, Rous AM, Souliere CM, Stemberger HLJ, Struthers DP, Vu M, Ward TD, Zolderdo AJ, Cooke SJ (2015) Being relevant: practical guidance for early career researchers interested in solving conservation problems. Glob Ecol Conserv 4:334–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.07.013

Coffait L (2017) Academics as policy entrepreneurs? Prepare to fight for your ideas (if you want to win), Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/academics-as-policy-entrepreneurs-prepare-to-fight-for-your-ideas-if-you-want-to-win/ . Accessed 9 July 2018

Colglazier B (2016) Encourage governments to heed scientific advice. Nature 537(7622):587. https://doi.org/10.1038/537587a

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Collins P (2011) Quality control in scientific policy advice: the experience of the Royal Society. Polit Scient Adv https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511777141.018

Crouzat E, Arpin I, Brunet L, Colloff MJ, Turkelboom F, Lavorel S (2018) Researchers must be aware of their roles at the interface of ecosystem services science and policy. Ambio 47(1):97–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0939-1

Crow D, Jones M (2018) Narratives as tools for influencing policy change. Policy Polit 46(2):217–234. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230061022899

Datta A (2018, July 11) Complexity and paradox: lessons from Indonesia. On Think Tanks https://onthinktanks.org/articles/complexity-and-paradox-lessons-from-indonesia/ . Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Docquier D (2017) Communicating your research to policy makers and journalists–Author Services. https://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/communicating-science-to-policymakers-and-journalists/ . Accessed 9 July 2018

Dodsworth S, Cheeseman N (2018) Five lessons for researchers who want to collaborate with governments and development organisations but avoid the common pitfalls. LSE Impact Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2018/02/05/five-lessons-for-researchers-who-want-to-collaborate-with-governments-and-development-organisations-but-avoid-the-common-pitfalls/ . Accessed 9 July 2018

Donnelly CA, Boyd I, Campbell P, Craig C, Vallance P, Walport M, Whitty CJM, Woods E, Wormald C (2018) Four principles to make evidence synthesis more useful for policy. Nature 558(7710):361–364. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05414-4

Douglas H (2012) Weighing complex evidence in a democratic society. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 22(2):139–162. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2012.0009

Article MathSciNet PubMed Google Scholar

Douglas H (2015) Politics and science: untangling values, ideologies, and reasons. Ann Am Acad Political Social Sci 658(1):296–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214557237

Echt L (2017a) “Context matters”: a framework to help connect knowledge with policy in government institutions, LSE Impact blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2017/12/19/context-matters-a-framework-to-help-connect-knowledge-with-policy-in-government-institutions/ Accessed 10 July 2018

Echt L (2017b) How can we make our research to be policy relevant? | Politics and Ideas: A Think Net, Politics and Ideas. http://www.politicsandideas.org/?p=3602 . Accessed 10 July 2018

Editorial (1972) Science research council advises the government. Nature 239(5370):243–243. https://doi.org/10.1038/239243a0 . Nature Publishing Group

Eisenstein M (2017) The needs of the many. Nature 551. https://doi.org/10.1038/456296a .

Evans J (2013, Feburary 19) How arts and humanities can influence public policy. HuffPost . https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/jules-evans/arts-humanities-influence-public-policy_b_2709614.html . Accessed 9 July 2018

Evans MC, Cvitanovic C (2018) An introduction to achieving policy impact for early career researchers. Palgrave Commun 4(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0144-2

Fafard P (2015) Beyond the usual suspects: using political science to enhance public health policy making. J Epidemiol Commun Health 1129:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204608 .

Farmer R (2010) How to influence government policy with your research: tips from practicing political scientists in government. Political Sci Polit 43(4):717–719. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096510001368

Fernández RJ (2016) How to be a more effective environmental scientist in management and policy contexts. Environ Sci & Policy 64:171–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2016.07.006

Fischoff M (2015) How can academics engage effectively in public and political discourse? At a 2015 conference, experts described how and why academics should reach out. Network for Business Sustainability

Fleming AH, Pyenson ND (2017) How to produce translational research to guide arctic policy. BioScience 67(6):490–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix002

Flinders M, Wood M, Cunningham M (2016) The politics of co-production: risks, limits and pollution. Evid Policy 12(2):261–279. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14412037949967

Game ET, Schwartz MW, Knight AT (2015) Policy relevant conservation science. Conserv Lett 8(5):309–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12207

Garrett T (2018) Moving an Evidence-based Policy Agenda Forward: Leadership Tips from the Field. NASN Sch Nurse 33(3):158–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942602X18766481

Gigerenzer G, Selten R (2001) The adaptive toolbox. In: G. Gigerenzer, R. Selten (eds) Bounded rationality The adaptive toolbox. MIT Press: Cambridge, pp. 37–50

Gluckman P (2014) The art of science advice to the government. Nature 507:163–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/507163a

Goodwin M (2013) How academics can engage with policy: 10 tips for a better Conversation, The Guardian . https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2013/mar/25/academics-policy-engagement-ten-tips

Gough D, Oliver S and Thomas J (2012) Introducing systematic reviews. In: An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

Graffy EA (1999) Enhancing policy-relevance without burning up or burning out: a strategy for scientists, in Science into policy: water in the public realm. The Association, pp. 293–298. http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=UA&search_mode=AdvancedSearch&qid=3&SID=D3Y7AMjSYyfgCmiXBUw&page=21&doc=208 . Accessed 9 Jul 2018

Green D (2016) How academics and NGOs can work together to influence policy: insights from the InterAction report, LSE Impact blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/09/23/how-academics-and-ngos-can-work-together-to-influence-policy-insights-from-the-interaction-report/ . Accessed 10 July 2018

Green LW, Glasgow RE, Atkins D, Stange K (2009) Making evidence from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning, and practice. slips “Twixt Cup and Lip”. Am J Prev Med 37(6 SUPPL. 1):S187–S191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.017

Haddon C, Devanny J, Forsdick PC, Thompson PA (2015) What is the value of history in policymaking? https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/what-value-history-policymaking . Accessed 10 July 2018

Haidt J (2001) The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev 108(4):814–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hammersley M (2013) The myth of research-based policy and practice

Havens B (1992) Making research relevant to policy. Gerontologist 32(2):273. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/32.2.273

Hayes S, Wilson C (2018) Being ‘resourceful’ in academic engagement with parliament | Wonkhe | Comment, Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/being-resourceful-in-academic-engagement-with-parliament/ . Accessed 12 July 2018

Haynes AS, Derrick GE, Chapman S, Redman S, Hall WD, Gillespie J, Sturk H (2011) From “our world” to the “real world”: Exploring the views and behaviour of policy-influential Australian public health researchers. Social Sci Med 72(7):1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.004

Head BW (2010) Reconsidering evidence-based policy: key issues and challenges. Policy Soc 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2010.03.001

Hillman N (2016) The 10 commandments for influencing policymakers | THE Comment, Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/comment/the-10-commandments-for-influencing-policymakers . Accessed 9 July 2018

Himmrich J (2016) How should academics interact with policy makers? Lessons on building a long-term advocacy strategy. LSE Impact Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/06/20/how-should-academics-interact-with-policy-makers-lessons-on-building-a-longterm-advocacy-strategy/ . Accessed 10 July 2018

Hutchings JA, Stenseth NC (2016) Communication of science advice to government. Trends Ecol Evol 31(1):7–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.10.008

Jasanoff S, Polsby NW (1991) The fifth branch: science advisers as policymakers. Contemp Sociol 20(5):727. https://doi.org/10.2307/2072218

Jo Clift Consulting (2016) Are you trying to get your voice heard in Government?–Jo Clift’s Personal Website. http://jocliftconsulting.strikingly.com/blog/are-you-trying-to-get-your-voice-heard-in-government . Accessed 10 July 2018

John P (2003) Is there life after policy streams, advocacy coalitions, and punctuations: using evolutionary theory to explain policy change? Policy Stud J 31(4):481–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-0072.00039

Jones BD, Thomas HF (2017) The cognitive underpinnings of policy process studies: Introduction to a special issue of Cognitive Systems Research. Cogn Syst Res 45:48–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.04.003

Jones M, Crow D (2018) Mastering the art of the narrative: using stories to shape public policy–Google Search, LSE Impact blog. https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=astering+the+art+of+the+narrative%3A+using+stories+to+shape+public+policy&rlz=1C1GGRV_en-GBGB808GB808&oq=astering+the+art+of+the+narrative%3A+using+stories+to+shape+public+policy&aqs=chrome..69i57.17213j0j4&sourceid=chrom Accessed 6 Aug 2018

Jones Michael D, Anderson Crow D (2017) How can we use the “science of stories” to produce persuasive scientific stories. Palgrave Commun 3(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0047-7

Kahneman DC, Patrick E (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Allen Lane. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781912453207

De Kerckhove DT, Rennie MD, Cormier R (2015) Censoring government scientists and the role of consensus in science advice: a structured process for scientific advice in governments and peer-review in academia should shape science communication strategies. EMBO Rep 16(3):263–266. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201439680

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kerr EA, Riba M, Udow-Phillips M (2015) Helping health service researchers and policy makers speak the same language. Health Serv Res 50(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12198

King A (2016) Science, politics and policymaking. EMBO Rep 17(11):1510–1512. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201643381

Kingdon J Thurber J (1984) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. https://schar.gmu.edu/sites/default/files/current-students/Courses/Fall_2017/PUAD/Regan-PUAD-540-002-Fall-17.pdf . Accessed 31 Jan 2018

Knottnerus JA, Tugwell P (2017) Methodology of the “craft” of scientific advice for policy and practice. J Clin Epidemiol 82:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.005

Koshland Jr. DE, Koshland Jr. DE, Koshland DE, Abelson PH (1988) Science advice to the president. Science 242(4885):1489. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.242.4885.1489

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Krige J (1990) Scientists as Policy-makers - British Physicists Advice to Their Government on Membership of CERN (1951-1952). Science History Publications, U.S.A. http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=UA&-search_mode=AdvancedSearch&qid=3&SID=D3Y7AMjSYyfgCmiXBUw&page=11&doc=105 Accessed 9 July 2018

Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, McLeod CB, Abelson J (2003) How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q 81(2):221–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052

Lawler A (1997) Academy seeks government help to fight openness law. Science 473. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5325.473

de Leeuw E, McNess A, Crisp B, Stagnitti K (2008) Theoretical reflections on the nexus between research, policy and practice. Critical Public Health https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590801949924

Lepkowski W (1984) Heritage-foundation science policy advice for reagan. Chem Eng News 62(51):20–21. https://doi.org/10.1021/cen-v062n051.p020

Lewis PG (2013) Policy thinking, fast and slow: a social intuitionist perspective on public policy processes. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2300479 . Accessed 17 July 2018

Lloyd J (2016) Should academics be expected to change policy? Six reasons why it is unrealistic for research to drive policy change, LSE Impact Blod. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/05/25/should-academics-be-expected-to-change-policy-six-reasons-why-it-is-unrealistic/ . Accessed 9 July 2018

Locock L, Boaz A (2004) Research, policy and practice–worlds apart? Social Policy Soc https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746404002003

Lucey JM, Palmer G, Yeong KL, Edwards DP, Senior MJM, Scriven SA, Reynolds G, Hill JK (2017) Reframing the evidence base for policy-relevance to increase impact: a case study on forest fragmentation in the oil palm sector. J Appl Ecol 54(3):731–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12845

Maddox G (1996) Policy-relevant health services research: who needs it? J Health Serv Res Policy 1(3):167–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581969600100309

Majone G (1989) Evidence, argument, and persuasion in the policy process. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300052596/evidence-argument-and-persuasion-policy-process . Accessed 17 July 2018

Malakoff D (2017) A battle over the “best science. Science. Am Assoc Advan Sci 1108–1109. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.355.6330.1108

Marshall E (1980) Advising reagan on science policy. Science 210(4472):880–881. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.210.4472.880

Marshall N, Cvitanovic C (2017) Ten top tips for social scientists seeking to influence policy, LSE Impact Blog

Masood E (1999) UK panel formed to rebuild trust in government science advice. Nature 397(6719):458. https://doi.org/10.1038/17161

Maybin J (2016) How proximity and trust are key factors in getting research to feed into policymaking, LSE Impact Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/09/12/how-proximity-and-trust-are-key-factors-in-getting-research-to-feed-into-policymaking/ . Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Mayer J (1982) Science advisers to the government. Science 215(4535):921. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.215.4535.921

Maynard, A. (2015) Is public engagement really career limiting? Times Higher Education

Mazanderani F and Latour B (2018) The Whole World is Becoming Science Studies: Fadhila Mazanderani Talks with Bruno Latour. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 4(0): 284. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2018.237

Morandi L (2009) Essential nexus. how to use research to inform and evaluate public policy. Am J Prev Med 36(2 SUPPL.):S53–S54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.005

Morgan MG, Houghton A, Gibbons JH (2001) Science and government: Improving science and technology advice for congress. Science . 1999–2000. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1065128

NCCPE (2018) How can you engage with policy makers? https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/do-engagement/understanding-audiences/policy-makers . Accessed 10 July 2018

Nichols RW (1972) Some practical problems of scientist-advisers. Minerva 10(4):603–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01695907

Nichols RW (1988) Science and technology advice to government. To not know is no sin; To not ask is. Technol Soc 10(3):285–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-791X(88)90011-5

Norse D (2005) The nitrogen cycle, scientific uncertainty and policy relevant science. Sci China Ser C, Life Sci / Chin Acad Sci 48(Suppl 2):807–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03187120

Nutley SM, Walter I, Davies HTO (2007) Using evidence: how research can inform public services. Policy Press. https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/U/bo13441009.html . Accessed 21 Jan 2019

Oakley A, Strange V, Toroyan T, Wiggins M, Roberts I, Stephenson J (2003) Using random allocation to evaluate social interventions: three recent U.K. examples. Ann Am Acad Political Social Sci 589(1):170–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203254765

Olander L, Polasky S, Kagan JS, Johnston RJ, Wainger L, Saah D, Maguire L, Boyd J, Yoskowitz D (2017) So you want your research to be relevant? Building the bridge between ecosystem services research and practice. Ecosyst Serv 26:170–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.06.003

Oliver KA, de Vocht F (2015) Defining “evidence” in public health: a survey of policymakers’ uses and preferences. Eur J Public Health. ckv082. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv082

Oliver K, Faul MV (2018) Networks and network analysis in evidence, policy and practice. Evidence and Policy 14(3): 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426418X15314037224597

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J (2014) A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

Ostrom E (2007a) Institutional rational choice: an assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework. Theor Policy Process . 21–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Ostrom E (2007b) Sustainable social-ecological systems: an impossibility. Presented at the 2007 Annual Meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, “Science and Technology for Sustainable Well-Being ” . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.997834

Pain E (2014) How scientists can influence policy. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.caredit.a1400042

Parkhurst J (2017) The politics of evidence: from evidence-based policy to the good governance of evidence. Routledge Studies in Governance and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315675008

Book Google Scholar

Parry-Davies E, Newell P (2014, July, 21) 10 ways to make public engagement work for you | Higher Education Network | The Guardian. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2014/jul/21/10-ways-make-public-engagement-work-for-you . Accessed 10 July 2018

Petes LE, Meyer MD (2018) An ecologist’s guide to careers in science policy advising. Front Ecol Environ 16(1):53–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1761

Petticrew M, Roberts H (2008) Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide, systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Sociol Health Illness. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

Pielke RA (2007) The honest broker: making sense of science in policy and politics. Honest Broker https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511818110

POST (2017) Getting your research into parliament-Author Services. https://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/getting-your-research-into-parliament/ . Accessed 9 July 2018

Prehn T (2018, May 24) Thomas Prehn’s innovation diary: What I learned at MindLab. Apolitical

Quarmby S (2018) Evidence-informed policymaking: does knowledge brokering work? LSE Impact Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/evidence-informed-policymaking-knowledge-brokers/

Reed, M. and Evely, A. (2016) How can your research have more impact? Five key principles and practical tips for effective knowledge exchange. LSE Impact blog. pp. 1–5. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2015/07/07/how-can-your-research-have-more-impact-5-key-principles-tips/ . Accessed 10 July 2018

Rose DC (2015) The case for policy-relevant conservation science. Conserv Biol 29(3):748–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12444

Sapolsky HM (1968) Science advice for state and local government. Science 160(3825):280–284. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.160.3825.280